8.7 Embryonic Development of the Respiratory System

Learning Objectives

By this section, you will be able to:

- Create a timeline of the phases of respiratory development in the foetus

- Propose reasons for foetal breathing movements

- Explain how the lungs become inflated after birth

Development of the respiratory system begins early in the foetus. It is a complex process that includes many structures, most of which arise from the endoderm. From as early as week 10 of gestation the foetus can be observed making breathing movements, however it is more evident in later weeks with ~15% of cases observing foetal breathing between weeks 24 to 28, and ~35% of foetal breathing can be observed in weeks 30 onwards. Until birth, however, the mother provides all of the oxygen to the foetus as well as removes all of the foetal carbon dioxide via the placenta.

Timeline

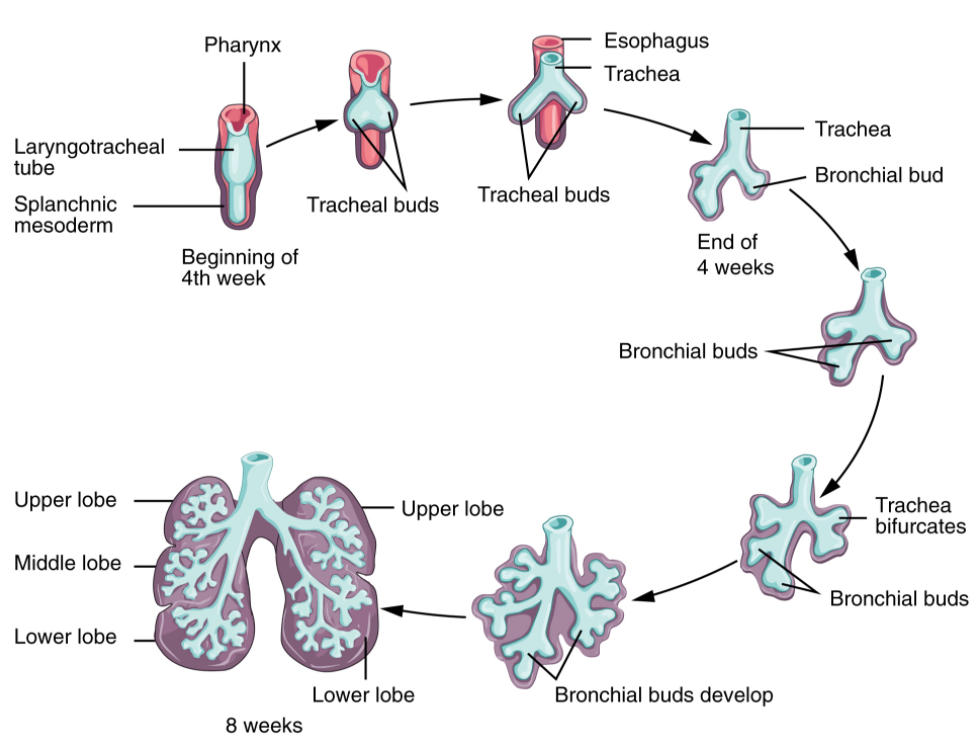

The development of the respiratory system begins at about week 4 of gestation. By week 28, enough alveoli have matured that a baby born prematurely at this time can usually breathe on its own. The respiratory system, however, is not fully developed until early childhood, when a full complement of mature alveoli is present.

Weeks 4–7

Respiratory development in the embryo begins around week 4. Ectodermal tissue from the anterior head region invaginates posteriorly to form olfactory pits, which fuse with endodermal tissue of the developing pharynx. An olfactory pit is one of a pair of structures that will enlarge to become the nasal cavity. At about this same time, the lung bud forms. The lung bud is a dome-shaped structure composed of tissue that bulges from the foregut. The foregut is endoderm just inferior to the pharyngeal pouches. The laryngotracheal bud is a structure that forms from the longitudinal extension of the lung bud as development progresses. The portion of this structure nearest the pharynx becomes the trachea, whereas the distal end becomes more bulbous, forming bronchial buds. A bronchial bud is one of a pair of structures that will eventually become the bronchi and all other lower respiratory structures (Figure 8.7.1).

Weeks 7–16

Bronchial buds continue to branch as development progresses until all of the segmental bronchi have been formed. Beginning around week 13, the lumens of the bronchi begin to expand in diameter. By week 16, respiratory bronchioles form. The foetus now has all major lung structures involved in the airway.

Weeks 16–24

Once the respiratory bronchioles form, further development includes extensive vascularisation, or the development of the blood vessels, as well as the formation of alveolar ducts and alveolar precursors. At about week 19, the respiratory bronchioles have formed. In addition, cells lining the respiratory structures begin to differentiate to form type I and type II pneumocytes. Once type II cells have differentiated, they begin to secrete small amounts of pulmonary surfactant. Around week 20, foetal breathing movements may begin.

Weeks 24–TERM

Major growth and maturation of the respiratory system occurs from week 24 until term. More alveolar precursors develop, and larger amounts of pulmonary surfactant are produced. Surfactant levels are not generally adequate to create effective lung compliance until about the eighth month of pregnancy. The respiratory system continues to expand, and the surfaces that will form the respiratory membrane develop further. At this point, pulmonary capillaries have formed and continue to expand, creating a large surface area for gas exchange. The major milestone of respiratory development occurs at around week 28, when sufficient alveolar precursors have matured so that a baby born prematurely at this time can usually breathe on its own. However, alveoli continue to develop and mature into childhood. A full complement of functional alveoli does not appear until around 8 years of age.

Foetal “Breathing”

Although the function of foetal breathing movements is not entirely clear, they can be observed starting at 20–21 weeks of development. Foetal breathing movements involve muscle contractions that cause the inhalation of amniotic fluid and exhalation of the same fluid, with pulmonary surfactant and mucus. Foetal breathing movements are not continuous and may include periods of frequent movements and periods of no movements. Maternal factors can influence the frequency of breathing movements. For example, high blood glucose levels, called hyperglycaemia, can boost the number of breathing movements. Conversely, low blood glucose levels, called hypoglycaemia, can reduce the number of foetal breathing movements. Tobacco use is also known to lower foetal breathing rates. foetal breathing may help tone the muscles in preparation for breathing movements once the foetus is born. It may also help the alveoli to form and mature. Foetal breathing movements are considered a sign of robust health.

Birth

Prior to birth, the lungs are filled with amniotic fluid, mucus, and surfactant. As the foetus is squeezed through the birth canal, the foetal thoracic cavity is compressed, expelling much of this fluid. Some fluid remains, however, but is rapidly absorbed by the body shortly after birth. The first inhalation occurs within 10 seconds after birth and not only serves as the first inspiration, but also acts to inflate the lungs. However, at birth the alveoli are not fully develop, this process will continue throughout the first two years of a child’s life. Pulmonary surfactant is critical for inflation to occur, as it reduces the surface tension of the alveoli. Preterm birth around 26 weeks frequently results in severe respiratory distress, although with current medical advancements, some babies may survive. Prior to 26 weeks, sufficient pulmonary surfactant is not produced, and the surfaces for gas exchange have not formed adequately; therefore, survival is low.

Disorders of the Respiratory System: Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (or infant respiratory distress syndrome IRDS) primarily occurs in infants born prematurely. Up to 50 percent of infants born between 26 and 28 weeks and fewer than 30 percent of infants born between 30 and 31 weeks develop RDS. RDS results from insufficient production of pulmonary surfactant, thereby preventing the lungs from properly inflating at birth. A small amount of pulmonary surfactant is produced beginning at around 20 weeks; however, this is not sufficient for inflation of the lungs. As a result, dyspnoea occurs and gas exchange cannot be performed properly. Blood oxygen levels are low, whereas blood carbon dioxide levels and pH are high.

The primary cause of RDS is premature birth, which may be due to a variety of known or unknown causes. Other risk factors include gestational diabetes, caesarean delivery, second-born twins, and family history of RDS. The presence of RDS can lead to other serious disorders, such as septicaemia (infection of the blood) or pulmonary haemorrhage. Therefore, it is important that RDS is immediately recognised and treated to prevent death and reduce the risk of developing other disorders.

Medical advances have resulted in an improved ability to treat RDS and support the infant until proper lung development can occur. At the time of delivery, treatment may include resuscitation and intubation if the infant does not breathe on his or her own. These infants would need to be placed on a ventilator to mechanically assist with the breathing process. If spontaneous breathing occurs, application of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) may be required. In addition, pulmonary surfactant is typically administered. Death due to RDS has been reduced by 50 percent due to the introduction of pulmonary surfactant therapy. Other therapies may include corticosteroids, supplemental oxygen, and assisted ventilation. Supportive therapies, such as temperature regulation, nutritional support, and antibiotics, may be administered to the premature infant as well.

Section Review

The development of the respiratory system in the foetus begins at about 4 weeks and continues into childhood. Ectodermal tissue in the anterior portion of the head region invaginates posteriorly, forming olfactory pits, which ultimately fuse with endodermal tissue of the early pharynx. At about this same time, a protrusion of endodermal tissue extends anteriorly from the foregut, producing a lung bud, which continues to elongate until it forms the laryngotracheal bud. The proximal portion of this structure will mature into the trachea, whereas the bulbous end will branch to form two bronchial buds. These buds then branch repeatedly, so that at about week 16, all major airway structures are present. Development progresses after week 16 as respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts form, and extensive vascularisation occurs. Alveolar type I cells also begin to take shape. Type II pulmonary cells develop and begin to produce small amounts of surfactant. As the foetus grows, the respiratory system continues to expand as more alveoli develop and more surfactant is produced. Beginning at about week 36 and lasting into childhood, alveolar precursors mature to become fully functional alveoli. At birth, compression of the thoracic cavity forces much of the fluid in the lungs to be expelled. The first inhalation inflates the lungs, foetal breathing movements begin around week 20 or 21 and occur when contractions of the respiratory muscles cause the foetus to inhale and exhale amniotic fluid. These movements continue until birth and may help to tone the muscles in preparation for breathing after birth and are a sign of good health.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.