2.2 Carbohydrates

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the role of carbohydrates in cells and in the extracellular materials of animals and plants

- Explain carbohydrate classifications

- List common monosaccharides, disaccharides and polysaccharides

Most people are familiar with carbohydrates, one type of macromolecule, especially when it comes to what we eat. To lose weight, some individuals adhere to “low-carb” diets. Athletes, in contrast, often “carb-load” before important competitions to ensure that they have enough energy to compete at a high level. Carbohydrates are, in fact, an essential part of our diet. Grains, fruits, and vegetables are all-natural carbohydrate sources that provide energy to the body, particularly through glucose, a simple sugar that is a component of starch and an ingredient in many staple foods. Carbohydrates also have other important functions in humans, animals, and plants.

Molecular Structures

The stoichiometric formula (CH2O)n, where n is the number of carbons in the molecule represents carbohydrates. In other words, the ratio of carbon to hydrogen to oxygen is 1:2:1 in carbohydrate molecules. This formula also explains the origin of the term “carbohydrate”: the components are carbon (“carbo”) and the components of water (hence, “hydrate”). Scientists classify carbohydrates into three subtypes: monosaccharides, disaccharides and polysaccharides.

Monosaccharides

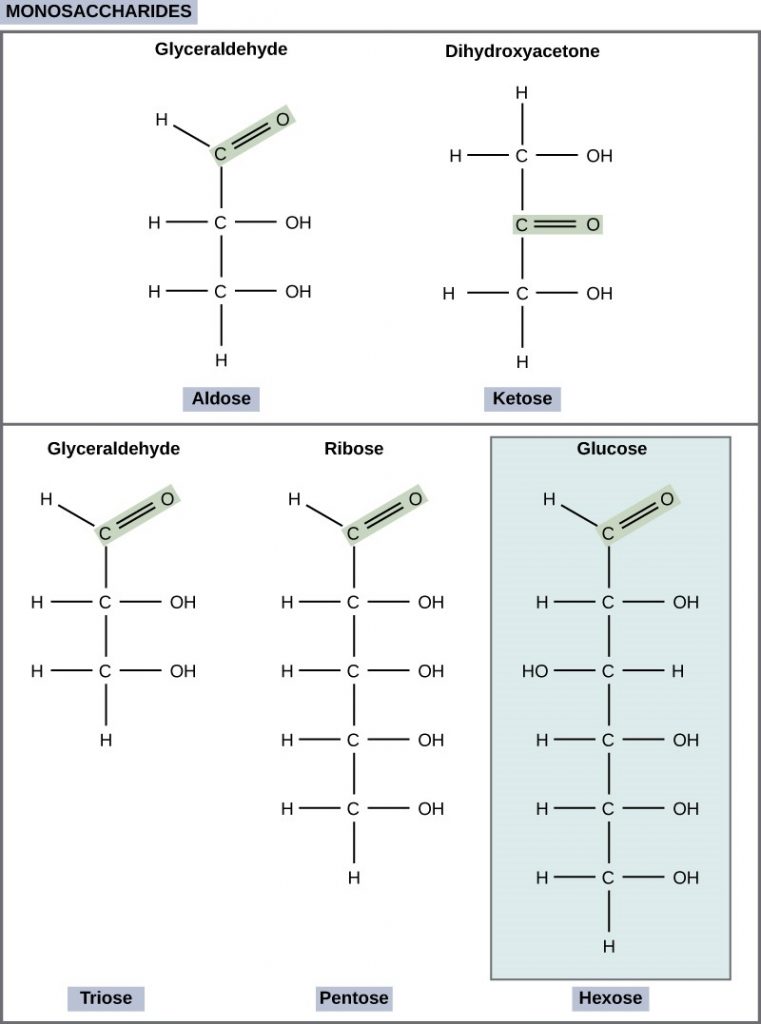

Monosaccharides (mono- = “one”; sacchar- = “sweet”) are simple sugars, the most common of which is glucose. In monosaccharides, the number of carbons usually ranges from three to seven. Most monosaccharide names end with the suffix-ose. If the sugar has an aldehyde group (the functional group with the structure R-CHO), it is an aldose, and if it has a ketone group (the functional group with the structure RC(=O)R’), it is a ketose. Depending on the number of carbons in the sugar, they can be trioses (three carbons), pentoses (five carbons), and/or hexoses (six carbons). Figure 2.2.1 illustrates monosaccharides.

The chemical formula for glucose is C6H12O6. In humans, glucose is an important source of energy. During cellular respiration, energy releases from glucose, and that energy helps make adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Plants synthesise glucose using carbon dioxide and water, and glucose in turn provides energy requirements for the plant. Humans and other animals that feed on plants often store excess glucose as catabolised (cell breakdown of larger molecules) starch.

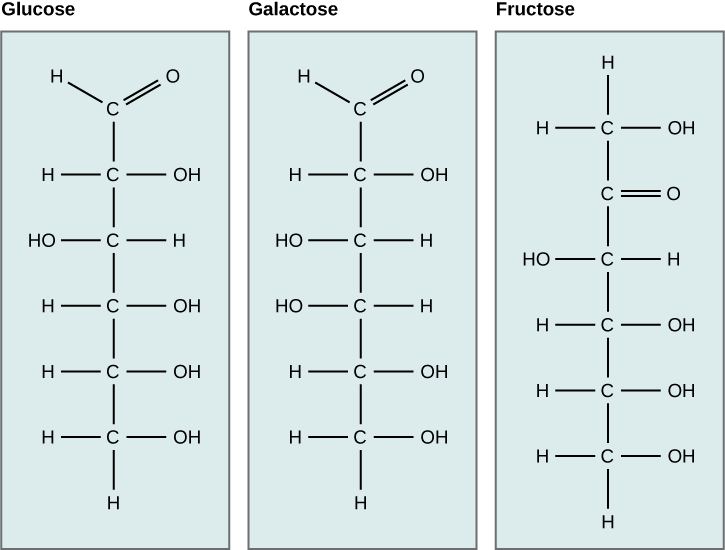

Galactose (part of lactose, or milk sugar) and fructose (found in sucrose, in fruit) are other common monosaccharides. Although glucose, galactose, and fructose all have the same chemical formula (C6H12O6), they differ structurally and chemically (and are isomers) because of the different arrangement of functional groups around the asymmetric carbon. All these monosaccharides have more than one asymmetric carbon (Figure 2.2.2).

What kind of sugars are these, aldose or ketose?

Glucose, galactose, and fructose are isomeric monosaccharides (hexoses), meaning they have the same chemical formula but have slightly different structures. Glucose and galactose are aldoses, and fructose is a ketose.

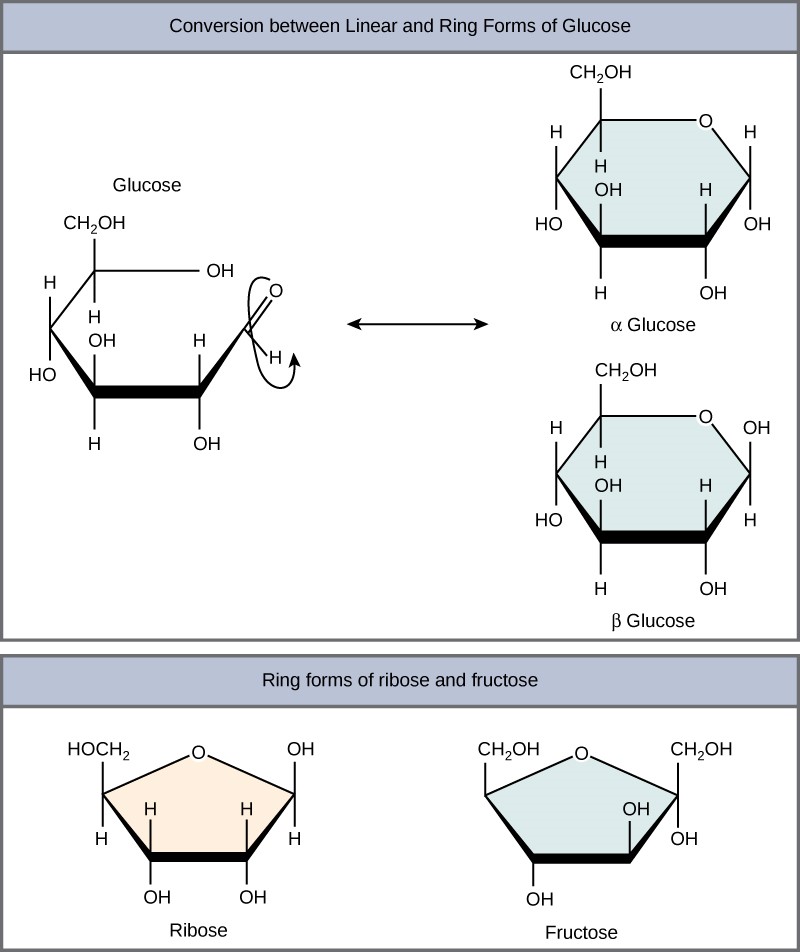

Monosaccharides can exist as a linear chain or as ring-shaped molecules. In aqueous solutions they are usually in ring forms (Figure 2.2.3). Glucose in a ring form can have two different hydroxyl group arrangements (OH) around the anomeric carbon (carbon 1 that becomes asymmetric in the ring formation process). If the hydroxyl group is below carbon number 1 in the sugar, it is in the alpha (α) position, and if it is above the plane, it is in the beta (β) position.

Disaccharides

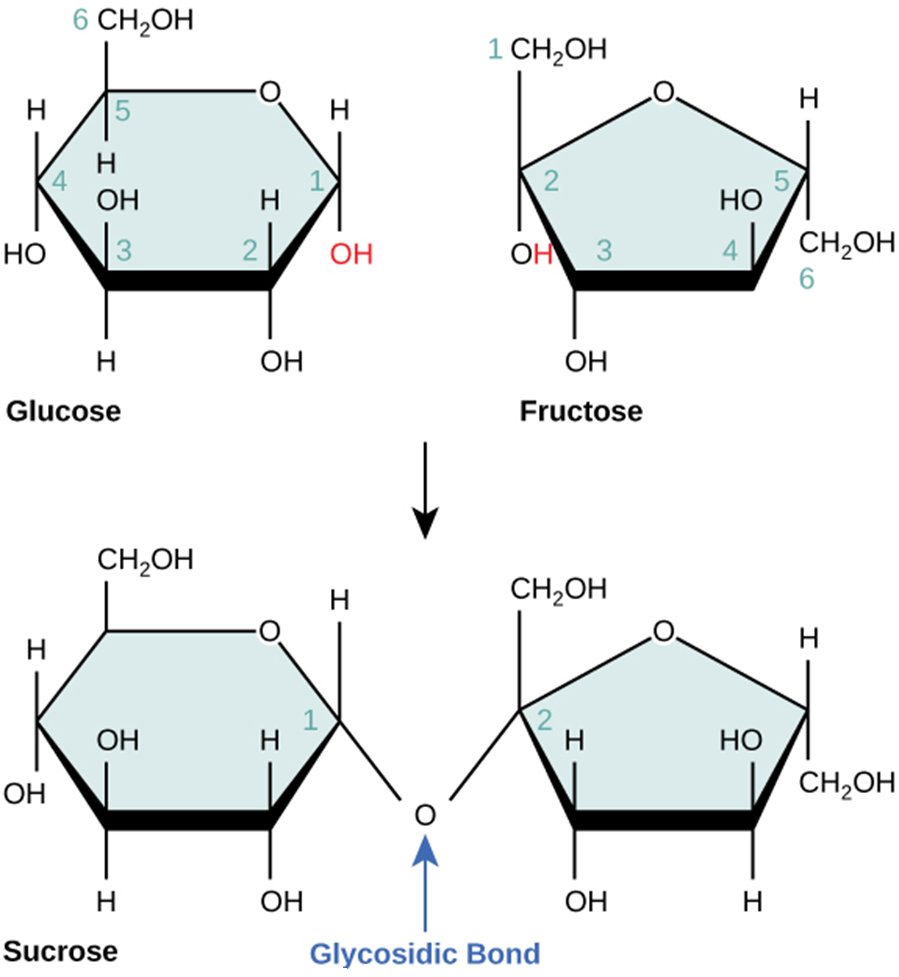

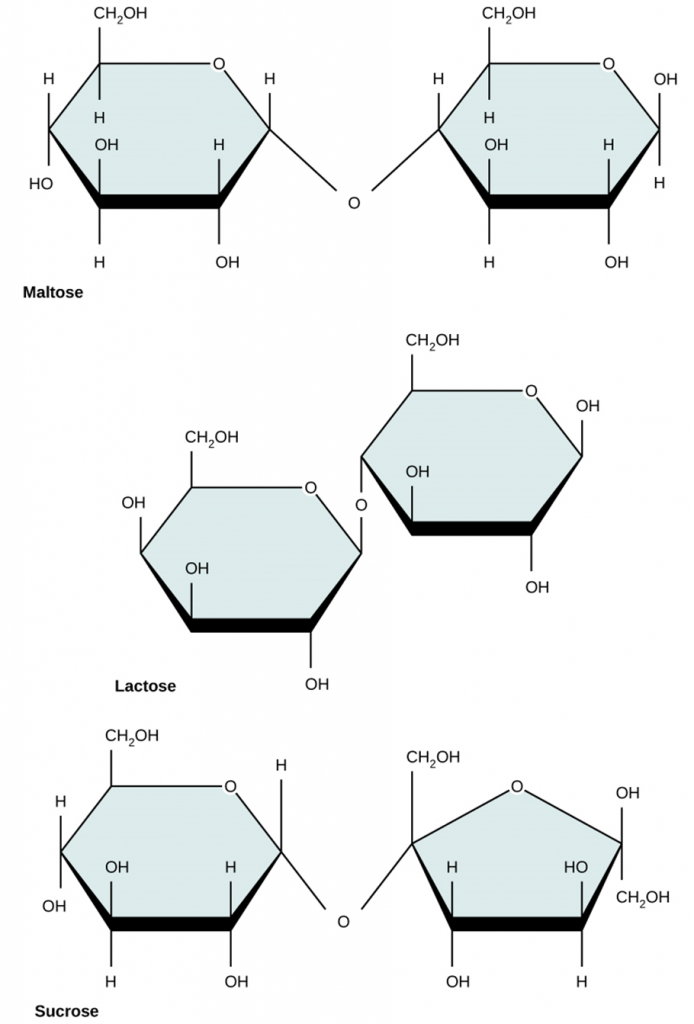

Disaccharides (di- = “two”) form when two monosaccharides undergo a dehydration reaction (or a condensation reaction or dehydration synthesis). During this process, one monosaccharide’s hydroxyl group combines with another monosaccharide’s hydrogen, releasing a water molecule and forming a covalent bond. A covalent bond forms between a carbohydrate molecule and another molecule (in this case, between two monosaccharides). Scientists call this a glycosidic bond (Figure 2.2.4). Glycosidic bonds (or glycosidic linkages) can be an alpha or beta type. An alpha bond is formed when the OH group on the carbon-1 of the first glucose is below the ring plane, and a beta bond is formed when the OH group on the carbon-1 is above the ring plane.

Common disaccharides include lactose, maltose, and sucrose (Figure 2.2.5). Lactose is a disaccharide consisting of the monomers; glucose and galactose. It is naturally in milk. Maltose, or malt sugar, is a disaccharide formed by a dehydration reaction between two glucose molecules. The most common disaccharide is sucrose, or table sugar, which is comprised of glucose and fructose monomers.

Polysaccharides

A long chain of monosaccharides linked by glycosidic bonds is a polysaccharide (poly- = “many”). The chain may be branched or unbranched, and it may contain different types of monosaccharides. The molecular weight (MW) may be 100,000 Daltons or more depending on the number of joined monomers. Starch, glycogen, cellulose and chitin are primary examples of polysaccharides.

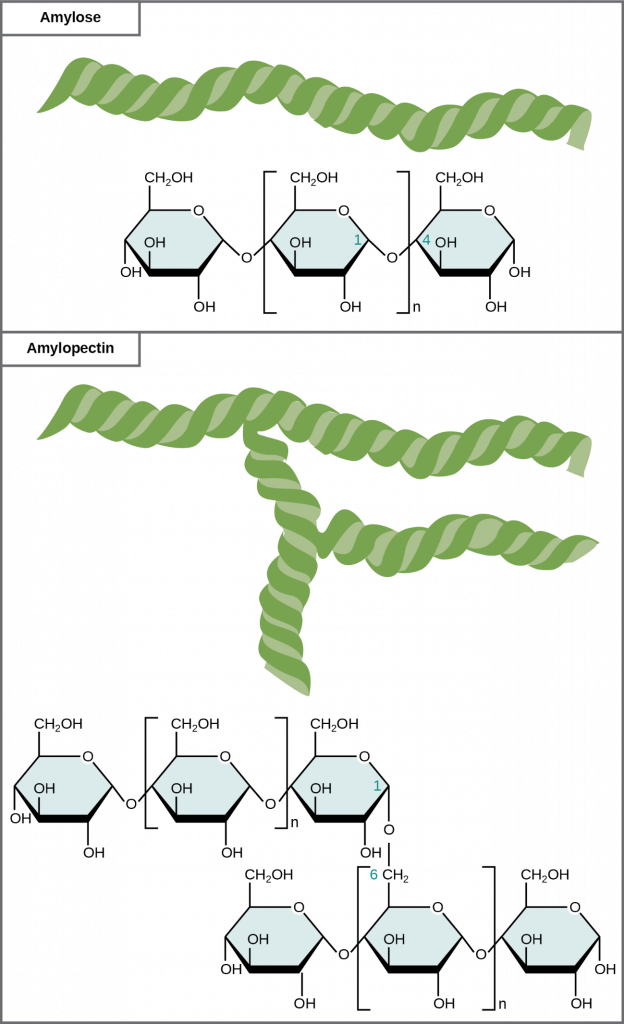

Plants store sugars in the form of starch. In plants, an amylose and amylopectin mixture (both glucose polymers) comprise these sugars. Plants can synthesise glucose, and they store the excess glucose, beyond their immediate energy needs, as starch in different plant parts, including roots and seeds. The starch in the seeds provides food for the embryo as it germinates and can also act as a food source for humans and animals. Enzymes break down the starch that humans consume, for example, an amylase present in saliva catalyses, or breaks down this starch into smaller molecules, such as maltose and glucose. The cells can then absorb the glucose.

Glucose starch comprises monomers that are joined by α 1-4 or α 1-6 glycosidic bonds. The numbers 1-4 and 1-6 refer to the carbon number of the two residues that have joined to form the bond. As Figure 2.2.6 illustrates, unbranched glucose monomer chains (only α 1-4 linkages) form the starch; whereas, amylopectin is a branched polysaccharide (α 1-6 linkages at the branch points).

Glycogen is the storage form of glucose in humans and other vertebrates and is comprised of monomers of glucose. Glycogen is the animal equivalent of starch and is a highly branched molecule usually stored in liver and muscle cells. Whenever blood glucose levels decrease, glycogen breaks down to release glucose in a process scientists call glycogenolysis.

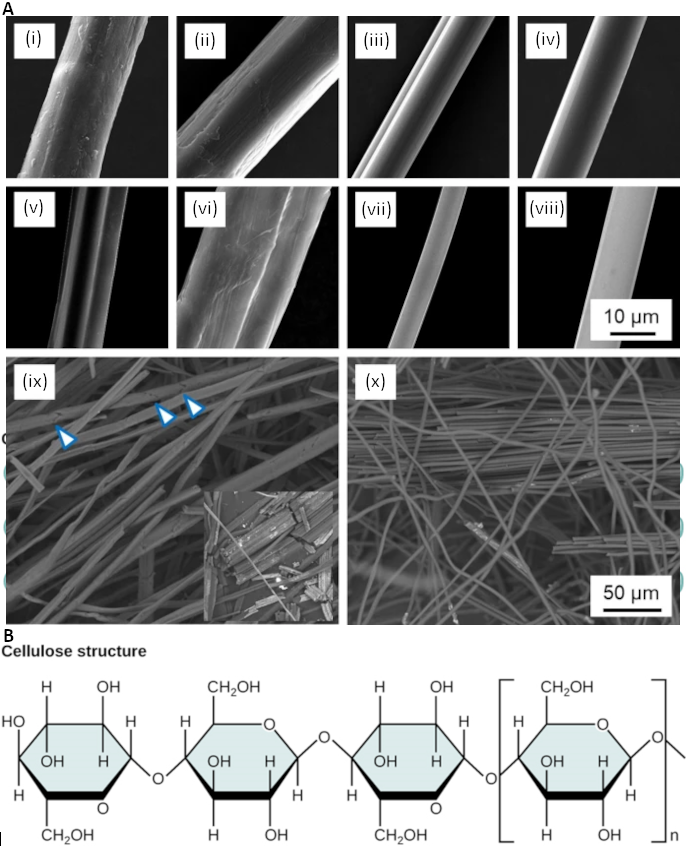

Cellulose is the most abundant natural biopolymer. Cellulose mostly comprises a plant’s cell wall. This provides the cell structural support. Wood and paper are mostly cellulosic in nature. Glucose monomers comprise cellulose that β 1-4 glycosidic bonds link (Figure 2.2.7).

As Figure 2.2.7 shows, every other glucose monomer in cellulose is flipped over, and the monomers are packed tightly as extended long chains. This gives cellulose its rigidity and high tensile strength—which is so important to plant cells. While human digestive enzymes cannot break down the β 1-4 linkage, herbivores such as cows, koalas, and buffalos are able, with the help of the specialised microorganisms in their stomach, to digest plant material that is rich in cellulose and use it as a food source. In some of these animals, certain species of bacteria and protists reside in the rumen (part of the herbivore’s digestive system) and secrete the enzyme cellulase. The appendix of grazing animals also contains bacteria that digest cellulose, giving it an important role in ruminants’ digestive systems. Cellulases can break down cellulose into glucose monomers that animals use as an energy source. Termites are also able to break down cellulose because of the presence of other organisms in their bodies that secrete cellulases.

Carbohydrates serve various functions in different animals. Arthropods (insects, crustaceans, and others) have an outer skeleton, the exoskeleton, which protects their internal body parts (as we see in the bee in Figure 2.2.8). This exoskeleton is made of the biological macromolecule chitin, which is a nitrogen-containing polysaccharide. It is made of repeating N-acetyl-β-d-glucosamine units, which are a modified sugar. Chitin is also a major component of fungal cell walls. Fungi are neither animals nor plants and form a kingdom of their own in the domain Eukarya.

Benefits of Carbohydrates

Are carbohydrates good for you? Some people believe that carbohydrates are bad and they should avoid them. Some diets completely forbid carbohydrate consumption, claiming that a low-carbohydrate diet helps people to lose weight faster. However, carbohydrates have been an important part of the human diet for thousands of years. Artifacts from ancient civilizations show the presence of wheat, rice, and corn in our ancestors’ storage areas.

As part of a well-balanced diet, we should supplement carbohydrates with proteins, vitamins, and fats. Calorie-wise, a gram of carbohydrate provides 4.3 Kcal. For comparison, fats provide 9 Kcal/g, a less desirable ratio. Carbohydrates contain soluble and insoluble elements. The insoluble part, fibre, is mostly cellulose. Fibre has many uses. It promotes regular bowel movement by adding bulk, and it regulates the blood glucose consumption rate. Fibre also helps to remove excess cholesterol from the body. Fibre binds to the cholesterol in the small intestine, then attaches to the cholesterol and prevents the cholesterol particles from entering the bloodstream. Cholesterol then exits the body via the faeces. Fibre-rich diets also have a protective role in reducing the occurrence of colon cancer. In addition, a meal containing whole grains and vegetables gives a feeling of fullness. As an immediate source of energy, glucose breaks down during the cellular respiration process, which produces ATP, the cell’s energy currency. Without consuming carbohydrates, we reduce the availability of “instant energy”. Eliminating carbohydrates from the diet may be necessary for some people, but such a step may not be healthy for everyone.

Career Connections: Registered Dietitian

Obesity is a worldwide health concern, and many diseases such as diabetes and heart disease are becoming more prevalent because of obesity. This is one of the reasons why people increasingly seek out registered dietitians for advice. Registered dietitians help plan nutrition programs for individuals in various settings. They often work with patients in health care facilities, designing nutrition plans to treat and prevent diseases. For example, dietitians may teach a patient with diabetes how to manage blood sugar levels by eating the correct types and amounts of carbohydrates. Dietitians may also work in nursing homes, schools, and private practices.

To become a registered dietitian, one needs to earn at least a bachelor’s degree in dietetics, nutrition, food technology, or a related field. In addition, registered dietitians must complete a supervised internship program and pass a national exam. Those who pursue careers in dietetics take courses in nutrition, chemistry, biochemistry, biology, microbiology, and human physiology. Dietitians must become experts in the chemistry and physiology (biological functions) of food (proteins, carbohydrates, and fats).

Biomedical Scientist

A biomedical scientist has at least a bachelor’s degree in biomedical science or science with a major in biomedical science. The majority of biomedical scientists also have an Honours degree (popular in countries such as Australia, Singapore, India and the United Kingdom) or a Masters degree (United States, Canada, Americas, Europe, parts of Asia and Africa), with PhDs also common. Biomedical scientists work in university, research institutes and commercial laboratories undertaking basic through to translational research projects aimed at improving our understanding of the human body in health and disease and investigating better ways to prevent, treat and diagnose diseases. Funding may be public in the form of government grants or commercial investment from the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

Section Review

Carbohydrates are a group of macromolecules that are a vital energy source for the cell and provide structural support to plant cells, fungi, and all of the arthropods that include lobsters, crabs, shrimp, insects, and spiders. Scientists classify carbohydrates as monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides depending on the number of monomers in the molecule. Monosaccharides are linked by glycosidic bonds that form as a result of dehydration reactions, forming disaccharides and polysaccharides with eliminating a water molecule for each bond formed. Glucose, galactose, and fructose are common monosaccharides; whereas, common disaccharides include lactose, maltose, and sucrose. Starch and glycogen, examples of polysaccharides, are the storage forms of glucose in plants and animals, respectively. The long polysaccharide chains may be branched or unbranched. Cellulose is an example of an unbranched polysaccharide; whereas, amylopectin, a constituent of starch, is a highly branched molecule. Glucose storage, in the form of polymers like starch of glycogen, makes it slightly less accessible for metabolism; however, this prevents it from leaking out of the cell or creating a high osmotic pressure that could cause the cell to uptake excessive water.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.

Note: Content and images from this chapter have been adapted from Biology 2nd edition by Mary Ann Clark, Jung Choi and Matthew Douglas, used under a CC-BY license.