11.8 Cartilaginous Joints

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the structural features of cartilaginous joints

- Distinguish between a synchondrosis and symphysis

- Give an example of each type of cartilaginous joint

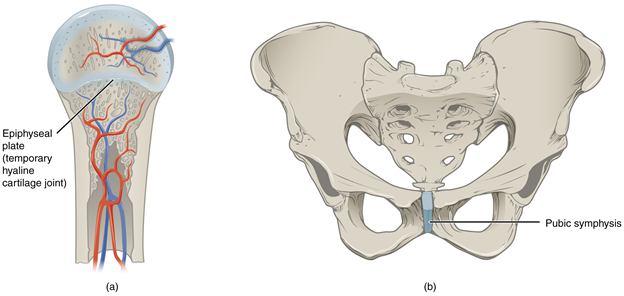

As the name indicates, at a cartilaginous joint, the adjacent bones are united by cartilage, a tough but flexible type of connective tissue. These types of joints lack a joint cavity and involve bones that are joined together by either hyaline cartilage or fibrocartilage (Figure 11.8.1). There are two types of cartilaginous joints. A synchondrosis is a cartilaginous joint where the bones are joined by hyaline cartilage. Also classified as a synchondrosis are places where bone is united to a cartilage structure, such as between the anterior end of a rib and the costal cartilage of the thoracic cage. The second type of cartilaginous joint is a symphysis, where the bones are joined by fibrocartilage.

Synchondrosis

A synchondrosis (“joined by cartilage”) is a cartilaginous joint where bones are joined together by hyaline cartilage, or where bone is united to hyaline cartilage. A synchondrosis may be temporary or permanent. A temporary synchondrosis is the epiphyseal plate (growth plate) of a growing long bone. The epiphyseal plate is the region of growing hyaline cartilage that unites the diaphysis (shaft) of the bone to the epiphysis (end of the bone). Bone lengthening involves growth of the epiphyseal plate cartilage and its replacement by bone, which adds to the diaphysis. For many years during childhood growth, the rates of cartilage growth and bone formation are equal and thus the epiphyseal plate does not change in overall thickness as the bone lengthens. During the late teens and early 20s, growth of the cartilage slows and eventually stops. The epiphyseal plate is then completely replaced by bone, and the diaphysis and epiphysis portions of the bone fuse together to form a single adult bone. This fusion of the diaphysis and epiphysis is a synostosis. Once this occurs, bone lengthening ceases. For this reason, the epiphyseal plate is a temporary synchondrosis. Because cartilage is softer than bone tissue, injury to a growing long bone can damage the epiphyseal plate cartilage, thus stopping bone growth and preventing additional bone lengthening.

Growing layers of cartilage also form synchondroses that join together the ilium, ischium, and pubic portions of the hip bone during childhood and adolescence. When body growth stops, the cartilage disappears and is replaced by bone, forming synostoses and fusing the bony components together into the single hip bone of the adult. Similarly, synostoses unite the sacral vertebrae that fuse together to form the adult sacrum.

Examples of permanent synchondroses are found in the thoracic cage. One example is the first sternocostal joint, where the first rib is anchored to the manubrium by its costal cartilage. (The articulations of the remaining costal cartilages to the sternum are all synovial joints.) Additional synchondroses are formed where the anterior end of the other 11 ribs is joined to its costal cartilage. Unlike the temporary synchondroses of the epiphyseal plate, these permanent synchondroses retain their hyaline cartilage and thus do not ossify with age. Due to the lack of movement between the bone and cartilage, both temporary and permanent synchondroses are functionally classified as a synarthrosis.

Symphysis

A cartilaginous joint where the bones are joined by fibrocartilage is called a symphysis (“growing together”). Fibrocartilage is extraordinarily strong because it contains numerous bundles of thick collagen fibres, thus giving it a much greater ability to resist pulling and bending forces when compared with hyaline cartilage. This gives symphyses the ability to strongly unite the adjacent bones but can still allow for limited movement to occur. Thus, a symphysis is functionally classified as an amphiarthrosis.

The gap separating the bones at a symphysis may be narrow or wide. Examples in which the gap between the bones is narrow include the pubic symphysis and the manubriosternal joint. At the pubic symphysis, the pubic portions of the right and left hip bones of the pelvis are joined together by fibrocartilage across a narrow gap. Similarly, at the manubriosternal joint, fibrocartilage unites the manubrium and body portions of the sternum.

The intervertebral symphysis is a wide symphysis located between the bodies of adjacent vertebrae of the vertebral column. Here a thick pad of fibrocartilage called an intervertebral disc strongly unites the adjacent vertebrae by filling the gap between them. The width of the intervertebral symphysis is important because it allows for small movements between the adjacent vertebrae. In addition, the thick intervertebral disc provides cushioning between the vertebrae, which is important when carrying heavy objects or during high-impact activities such as running or jumping.

Section Review

There are two types of cartilaginous joints. A synchondrosis is formed when the adjacent bones are united by hyaline cartilage. A temporary synchondrosis is formed by the epiphyseal plate of a growing long bone, which is lost when the epiphyseal plate ossifies as the bone reaches maturity. The synchondrosis is thus replaced by a synostosis. Permanent synchondroses that do not ossify are found at the first sternocostal joint and between the anterior ends of the bony ribs and the junction with their costal cartilage. A symphysis is where the bones are joined by fibrocartilage and the gap between the bones may be narrow or wide. A narrow symphysis is found at the manubriosternal joint and at the pubic symphysis. A wide symphysis is the intervertebral symphysis in which the bodies of adjacent vertebrae are united by an intervertebral disc.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.