10 Trevor the Fibber

Kara Tew

This chapter describes the creation of Trevor the Fibber, a re-imagining of Aaron Blabey’s (2017) popular childrens’ book Pig the Fibber.

CONNECTIONS TO THE AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM

Year 2 English

Language:

- ACELA1460 – Understand that spoken, visual and written forms of language are different modes of communication with different features and their use varies according to the audience, purpose, context and cultural background

Literature:

- ACELT1589 – Compare opinions about characters, events and settings in and between texts

- ACELT1590 – Discuss the characters and settings of different texts and explore how language is used to present these features in different ways

- ACELT1593 – Create events and characters using different media that develop key events and characters from literary texts

- ACELT1833 – Innovate on familiar texts by experimenting with character, setting or plot

Literacy:

- ACELY1670 – Use comprehension strategies to build literal and inferred meaning and begin to analyse texts by drawing on growing knowledge of context, language and visual features and print and multimodal text structures

- ACELY1672 – Re-read and edit text for spelling, sentence-boundary punctuation and text structure

Acknowledging technology literacy as one of the many literacies relevant in educational settings (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; New London Group, 1996; Siraj-Blatchford & Siraj-Blatchford, 2006), I used the Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, and Redefinition (SAMR) framework to consider how to meaningfully embed developmentally appropriate technology into the process of co-constructing the multimodal text Trevor the Fibber with my 8-year-old son (O.R.T). As a result, I decided to use kidspiration by Inspiration Software Inc. as a way of augmenting various scribing, mind-mapping and planning components as it not only offered a direct replacement for the traditional method, but it also enhanced the experience by allowing users to easily add supporting visual elements (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Puentedura, 2011). This tool also offered opportunities for significant task redesign (modification), by allowing O.R.T to take control of text entry more readily through voice-to text and predictive text prompts (Puentedura, 2011).

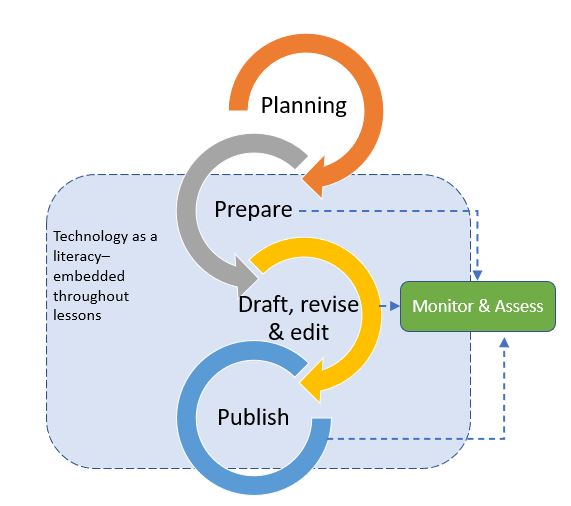

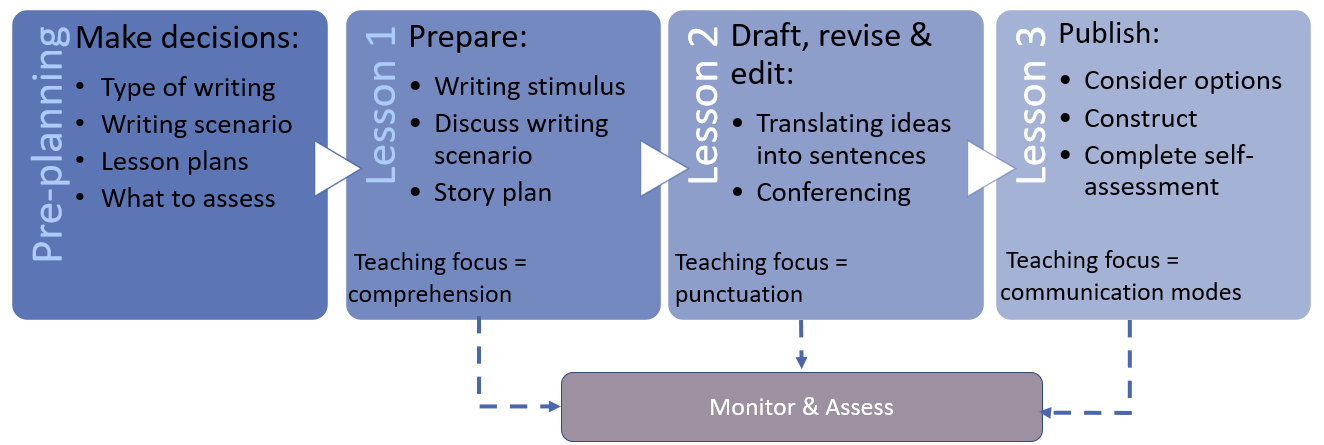

This image outlines the process that I followed:

Planning

A pre-planning stage provided overarching direction for lesson and assessment planning, and it was during this stage I decided we would create a multimodal text that was literary in nature and in a short, narrative format (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). As children are most engaged with learning when it is challenging but not frustrational, and when it appeals to their interests, I selected Pig the Fibber by Aaron Blabey (2017) as a stimulus because O.R.T had recently shown interest in discussing ethical concepts relating to friendship and he prefers humourous texts. I then reviewed Australian Curriculum Year 2 English and shaped three 40 to 50 minute heavily scaffolded lessons around the ‘prepare, draft, revise, edit, publish’ writing process, each incorporating a specific teaching focus with corresponding assessment and monitoring.

Prepare

Lesson 1 – Introduction

- What are we doing and why?

- Independent reading + ‘think aloud’ (ACELY1670)

- Mind map: What is friendship?

The aim of the first lesson was to prepare for writing and this involved establishing the writing context, discussing the selected text form and starting the process of generating and organising ideas (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). As children engage with learning better when they have a clear understanding of the process and output expectations (Ashman, 2018; Fellowes & Oakley, 2019), at the outset, I clearly articulated what we would be doing and why (and we frequently revisited this through all lessons).

As O.R.T had recently read other Pig the Pug books with high levels of fluency (i.e., pace, accuracy and automaticity, smoothness, and expressiveness), I gauged the stimulus text as appropriate for him to read aloud independently while incorporating a ‘think aloud’ strategy at designated points to show the comprehension strategies he was using to make meaning of the story (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Tompkins et al., 2018). I first demonstrated this explicit form of thinking using a different text (Tompkins et al., 2018). Post-reading we also discussed how the two semiotic systems of language and images are used to emphasise the relationship between Pig and Trevor, and building off this, we created a mind-map of friendship. Together, these activities were designed to enhance comprehension and stimulate thinking for the next activity while assessing all aspects of ACELY1670 (ACARA, n.d.; Chandler, 2017; Tompkins et al., 2018).

Lesson 1 – Body and Conclusion

Body

- Create the writing scenario

- Topic: friendship/lying

- Purpose: entertain

- Audience: children of similar age

- Text type: short narrative

- Planning the story

- Story web/plan

- Orientation – complication – resolution

Conclusion

- Review of story outline

- Discuss next steps

To help establish the writing scenario and plan the story, I described the writing activity (rewrite the story to show what would happen if Trevor was not a good friend) and discussed the structural features (orientation, complication and resolution) of a narrative text (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Following this we were able to decide on a topic, purpose and audience and building off our friendship mindmap, we worked together to complete a story planning framework (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Creating this web helped consolidate our thoughts within the structure of a narrative and provided a clear outline from which we could develop text (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

Draft, Revise and Edit

Lesson 2

Introduction

- Review outline:

- Verbal and visual walk through

Body

- Write draft text

- Revise text with conferencing

Conclusion

- Edit

- Discuss next steps

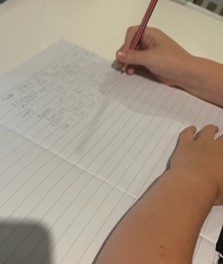

The aim of the second lesson was to draft, revise and edit our text, while considering a variety of different writing processes and observing writing conventions (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Given his age and skill level, O.R.T was first given the opportunity to write a first draft independently using our story plan as a guide (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). To encourage him to write freely and get as many thoughts as possible down, I did not interrupt to provide correction and only aided him as necessary for progressing the text (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Tompkins et al., 2018). Drafting with pencil and paper was not intended to be a handwriting lesson, but this mode of recording ideas was selected as it was the method which O.R.T was most easily able to produce free-flowing text (Ashman, 2018).

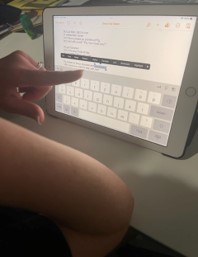

Once O.R.T had completed his handwritten draft, we collaboratively worked to revise the text, predominantly focussing on structural changes, additions/deletions to improve text clarity and vocabulary choices to enhance descriptions and rhyming (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). To maintain interest and ownership of the work, I used a conferencing-style method including demonstration and question prompts, which was facilitated by me having transferred text into an electronic format (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Tompkins et al., 2018).

The conclusion of this lesson was focussed on editing the final text, during which I assessed O.R.T’s ability to use punctuation in line with ACELY1672 (ACARA, n.d.).

Publish

Lesson 3 – Introduction

- Review the text

- Discuss multiliteracies & modes of communication

- Consider options for presentation

- Select tool for creating multimodal text

Rather than using a specific e-LEA approach to develop the text, a more traditional writing process was used, supported by technology (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). It was, therefore, not until the publishing stage that text was transformed into a multimodal format. Aligning with multiliteracies theory, O.R.T and I discussed how there are many ways that we make sense of the world and importance may vary depending on our social, cultural and technological surrounds, but that we can use different modes of communication to help support productive and receptive meaning-making (New London Group, 1996; Taylor & Leung, 2019). Further we discussed how technology can help bring together several modes to enhance semiosis/meaning-making (Mills & Unsworth, 2017; Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

What is multiliteracies theory?

- Literacy goes beyond a traditional definition and that we can be literate in many ways (e.g. computer, cultural, health).

- Literacies practiced or deemed important can be influenced by social, cultural and technological change.

- There are many modes of communication and technology can support delivery of these.

(Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

Lesson 3 – Body and Conclusion

Body

- Construct the multimodal story

- Import the text

- Select visuals

- Add details

- Record the audio

Conclusion

- Listen to the story

- Complete self-assessment

- Share the story

Providing O.R.T with this important background knowledge allowed us to have a two-way conversation about the modes of communication that we wanted to incorporate to support the message we would like to convey. Once we established this, we selected an appropriate tool (from a pre-curated list) suited to O.R.T’s level of technological literacy, thus allowing him to take control of operating the application and encourage personal pride in work (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Mills & Unsworth, 2017). Using My Story by Bright Bot Inc., O.R.T and I worked collaboratively to create our multimodal text which incorporated our final text, backgrounds, stock images, direct-to-screen drawing/writing and voice over.

OUTLINE OF THE CHILD’S LEARNING

While the development of the multimodal text touched on a broad range of aspects from the curriculum, each of the three lessons had a specific teaching and subsequent monitoring and assessment focus: reading comprehension strategies in lesson 1 (ACELY1670); punctuation in lesson 2 (ACELY1672); and understanding modes of communication in lesson 3 (ACELA1460) (ACARA, n.d.). I also collected data (completed activities and texts) which could be added to a portfolio and used as evidence of his understanding of text structures and language features of narrative texts, and ability to create short imaginative texts.

Noting that O.R.T had recently learnt about various comprehension strategies and that his classroom teacher regularly uses ‘think alouds’, I chose to incorporate an assessment of reading strategies using a student ‘think-aloud’ strategy in the first lesson (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). At various points during his reading, I asked O.R.T to ‘think-aloud’ while I recorded notes and later summarised on a rating scale. My notes and summary indicated that he understood how to use these strategies but could think a little more critically about his responses (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

| Pig the Fibber: ORT ‘Think-alouds’ notes (2/05/22) | ||

| Page number | Strategy used | O.R.T. response |

| Front cover | Predicting and inferring | Predicted that “Pig would make up lies so he could get what he wanted” and was able to point out how it looked like Pig was responsible for defacing part of the cover. |

| 2 | Text-to-self connection | Described how he would feel hurt if he was Trevor and Pig always blamed him. |

| 6 | Inferring | Stated that Pig emphasised the words “crazy” and “hours” because these are written differently to the other words. |

| 7 | Text-to-self connection | Described how he was thinking of mummy’s wedding dress and how he would “feel sad if someone ripped it up” because he knows how special it is. |

| 8 | Inferring andText-to-self connection | Stated that based on what Trevor said and the look on his face, he believed that Trevor was wondering whether they should be friends. He also described how he thought Pig’s actions were not the kind of things he would do to his friends because friends should look after each other. |

| 12 | Predicting | Predicted that Pig would “make up a lie to distract the owners” because Pig looked devious and he likes lying. |

| 16 | Predicting | Predicted that the “pink ball was going to fall on to his head before he gets to enjoy his treats”. |

| 20 | Inferring | Stated that Trevor was happy because he was smiling and hugging Pig. |

| Rating scale summary of O.R.T ‘Think alouds | ||||

| Skill or behaviour | Always | Mostly | Sometimes | Never |

| Selected strategy was appropriate | ||||

| Expresses thinking clearly | ||||

| Draws on both language and visual features | ||||

| Justifies response | ||||

Receptive modes (listening, reading and viewing)

O.R.T was able to demonstrate understanding for the text structures of a narrative. He monitors meaning and identifies literal and implied meaning, main ideas and supporting detail. He can make connections between texts by comparing content.

Productive modes (speaking, writing and creating)

O.R.T creates texts that show how images support the meaning of the text by drawing on his own experiences and imagination. O.R.T uses some punctuation accurately.

During the second lesson, O.R.T added punctuation and capital letters into the electronic version of the narrative text. I chose to do this electronically so he wasn’t encumbered by letter formation or spelling mistakes, and similar to the educator-led strategy described by Fellowes and Oakley (2019), I encouraged him to read the story aloud to help identify places where punctuation was required. Once he completed this activity, I talked him through the punctuation he had missed and I transferred information to a rating scale which indicated that there were some gaps in his knowledge which we could work on.

| Punctuation rating scale | ||||

| Name: O.R.T. (8/5/22) | ||||

| Skill or behaviour | Always | Mostly | Sometimes | Never |

| Capital letter for names | ||||

| Capital letter for start of sentence | ||||

| Full stops | ||||

| Comma | ||||

| Question mark | ||||

| Exclamation mark | ||||

| Speech marks | ||||

To assess understanding of different modes of communication, I used both self-assessment and anecdotal notes which I converted to a checklist. Notes captured how building on our discussion of multiliteracies, O.R.T engaged in two-way discussion regarding all aspects of presentation, including how we might incorporate different elements to enhance meaning. For example, we tried to select the dogs which showed the most appropriate facial expression for each page (Mills & Unsworth, 2017). Further, when recording the voiceover, I noted that O.R.T not only drew on his linguistic semiotic system, but he also employed hand gestures and sounds which he created by clapping his hands together and banging down his fists to emphasise the message he was delivering (Chandler, 2017; Mills & Unsworth, 2017).

| Observation | |

| Has a clear understanding of communication modes (including but not limited to spoken, visual and written) | ✓ |

| Can identify suitable modes of communication for use. | ✓ |

| Can justify choice of communication mode. | |

| Verbal recording supported text though use of expression to convey meaning. | ✓ |

| Verbal recording included additional elements (sound effects) to enhance meaning. | ✓ |

| Visual elements support text and enhance meaning making. | ✓ |

In an effort to provide feedback and closure, O.R.T and I talked through our final product, the steps we had taken to get there, and the assessment conducted (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). To instil further pride, we had a special viewing of the story with his Nanna who he identified on the self-assessment as someone he would like to share the story with (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

My lasting impression of this exercise was the importance of pre-planning. Prior to beginning this exercise and before each ‘lesson’ I spent time planning and researching suitable tools. There are so many different tools out there to support the development of a co-created multimodal text that pre-planning and research are needed to find the tool that is right for you and the child.

Key Takeaways

- Co-creating multimodal texts can be educational and FUN for everyone involved if you have the right attitude and create the right environment for your child/children.

- Watch for signs that the child has had enough for the day and come back to it later if need be to help keep the activity positive.

The Co-Created multimodal Text

The co-constructed text includes words and inspiration from Pig the Fibber by Aaron Blabey

Text and illustrations copyright © Aaron Blabey, 2015.

First published by Scholastic Australia Pty Limited in 2015.

Reproduced with permission from Scholastic Australia Pty Limited.

References

Ashman, A. (Ed.) (2018). Education for inclusion and diversity (6th ed.). Pearson Education Australia.

Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority [ACECQA]. (n.d.). Guidelines for documenting children’s learning. ACEQA. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-01/GuidelinesForDocumentingChildrensLearning%20.pdf

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (n.d.). F-10 Curriculum: English (Version 8.4). Australian Curriculum. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/english

Blabey, A. (2017). Pig the Fibber. Scholastic Australia.

Chandler, D. (2017). Semiotics: The basics (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Fellowes, J., & Oakley, G. (2019). Language, literacy and early childhood education (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Mills, K. and Unsworth, L. (2017). Multimodal literacy. In G. Noblit (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education (pp. 1-29). Oxford University Press. Retrieved April 30, 2022, from https://acuresearchbank.acu.edu.au/item/89v27/multimodal-literacy

New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social future. Harvard Education Review, 66(1), 60-92.

Puentedura, R. (2011). A brief introduction to TPCK and SAMR. Hiappasus. Retrieved April 30, 2022, from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2011/12/08/BriefIntroTPCKSAMR.pdf

Siraj-Blatchford, J. & Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2006). A guide to developing the ICT curriculum for early childhood education. Trentham books.

Taylor, S. & Leung, C. (2019). Multimodal literacy and social interaction: Young children’s literacy learning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00974-0

Tompkins, G., Smith, C., Campbell, R., & Green, D. (2018). Literacy for the 21st century: A balanced approach ebook. Pearson Education Australia.