1 Tiddler’s Late (Again)!

Sophie Woodward

While collaborating with my 5-year-old niece, Clara (who is in Prep), we co-constructed a multimodal story that gives an alternate reason for why Tiddler was late to class in Tiddler: The story-telling fish (Tiddler) by Julia Donaldson (2016). For this activity, I chose Holdaway’s (1979) Shared Reading strategy, while also drawing on the Shared Writing strategy and Tompkin’s (2016) Elements of Shared Reading (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). I also decided to use one of Fellowes and Oakley’s (2019) suggested stimuli for writing activities: children’s literature. This stimulus category was chosen because it is a motivating and engaging way to inspire writing, and children enjoy sharing their thoughts about books with others (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

Before creating with Clara, I determined, based on her previously observed skills, that she was in the emergent phase of writing development (able to write most letters and sound out some words) and phase 2 of reading development (enjoys being read to and retelling/creating texts) (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

CONNECTIONS TO THE AUSTRLALIAN CURRICULUM

There are several Content Descriptors from all three strands of the Australian Curriculum: English Foundation year level being assessed in this learning experience (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], n.d.). These include:

Language:

- ACELA1817 – know how to read and write some high-frequency words and other familiar words

- ACELA1433 – understand concepts about print and screen, including how books, film and simple digital texts work, and know some features of print, for example, directionality

- ACELA1435 – recognise that sentences are key units for expressing ideas

- ACELA1437– understand the use of vocabulary in familiar contexts related to everyday experiences, personal interests and topics taught at school

- ACELA1438 – understand how to use knowledge of letters and sounds including onset and rime to spell words

Literacy:

- ACELY1651 – create short texts to explore, record and report ideas and events using familiar words and beginning writing knowledge

ACELY1654 – construct texts using software including word processing programs

ACELY1650 – use comprehension strategies to understand and discuss texts listened to, viewed or read independently

Literature:

- ACELT1783 – Share feelings and thoughts about the events and characters in texts.

- ACELT1580 – Retell familiar literary texts through performance, use of illustrations and images

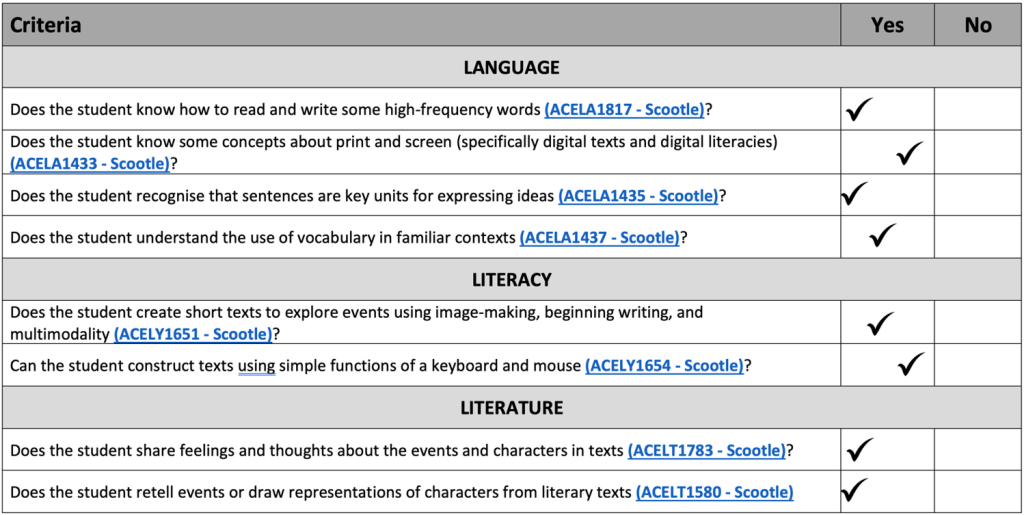

An Outline of Student Learning criteria sheet was created based on these Content Descriptors for completion at the end of the task.

Introduction to Activity

The five elements of literacy motivation are success, choice, challenge, interest, and purpose (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). With these in mind, I decided that I would give Clara a choice of stimulus books based on her interests. The options provided to Clara included The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson, which is a book I knew Clara loved and had read repeatedly. On the other hand, The Very Super Bear by Nick Bland was chosen as an option because I knew Clara had enjoyed other books by the same author but had not read this one. Ultimately, though, Clara made her choice when she was drawn to the colourful illustrations and the interestingly unfamiliar creatures in Tiddler by Julia Donaldson (2016). Clara remembered that Julia Donaldson had also written The Gruffalo, so she was eager to read another of her books.

We started with a Picture Walk of Tiddler (Ness, 2017). During the picture walk, I pointed out and defined vocabulary that I thought may be unfamiliar to Clara, such as ‘shoal’, ‘register’, and ‘tallest story’ (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). This activity aligns with ACELA1437, specifically the elaboration: discussing new vocabulary in texts (ACARA, n.d.). We also discussed the sea creatures we saw that were both familiar and unfamiliar. While looking through the book, I observed Clara getting curious about what would happen. Once we had read the book together, we watched an interactive re-telling on YouTube. Multiple exposures to new information or resources encourages deep learning and engagement (State of Victoria, 2017) and this particular video was chosen as I found it to be a dramatic and fun retelling that is engaging and entertaining.

While I had decided on the general outcome of the experience, it was important to me that Clara felt that it was her work and that her decisions had shaped the final product. Before our session, I had decided that I wanted to use a storybook as the inspiration for our multimodal text. I had also loosely decided that we should create an alternate ending for the chosen story as suggested in Fellowes and Oakley (2020) but was open to changing this if Clara felt strongly about doing something else that would also satisfy the assessment criteria. Ultimately, Clara decided that she wanted to create another reason why Tiddler could be late for school which, although different to my original idea, still fit the task perfectly.

Gathering Ideas using YouTube

After reading and watching Tiddler, Clara was very eager to look at more of the interesting sea creatures depicted in the book, so we decided to find some clips on YouTube. This was not part of my original plan, but I could see that it was something Clara really wanted to do. While watching the videos, we flipped through the book to find the same creature in its illustrated form. Although this activity may need to be modified during a whole class experience, depending on time restraints or access to resources, I found this to be a very worthwhile experience. Clara was able to recognise similarities and differences in the creatures between the videos and illustrations and shared with me a story about a time that she went fishing and crabbing with her dad, thereby relating the stimulus text to her own life (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Although this was not part of the assessable criterion, making links between a text and students’ own experiences does align with ACELY1650 (ACARA, n.d.). Clara was very taken with the seahorses we watched, so we used them (combined with her love of unicorns) as inspiration for one of the characters in her story – the sea-unicorn.

Drawing the Characters

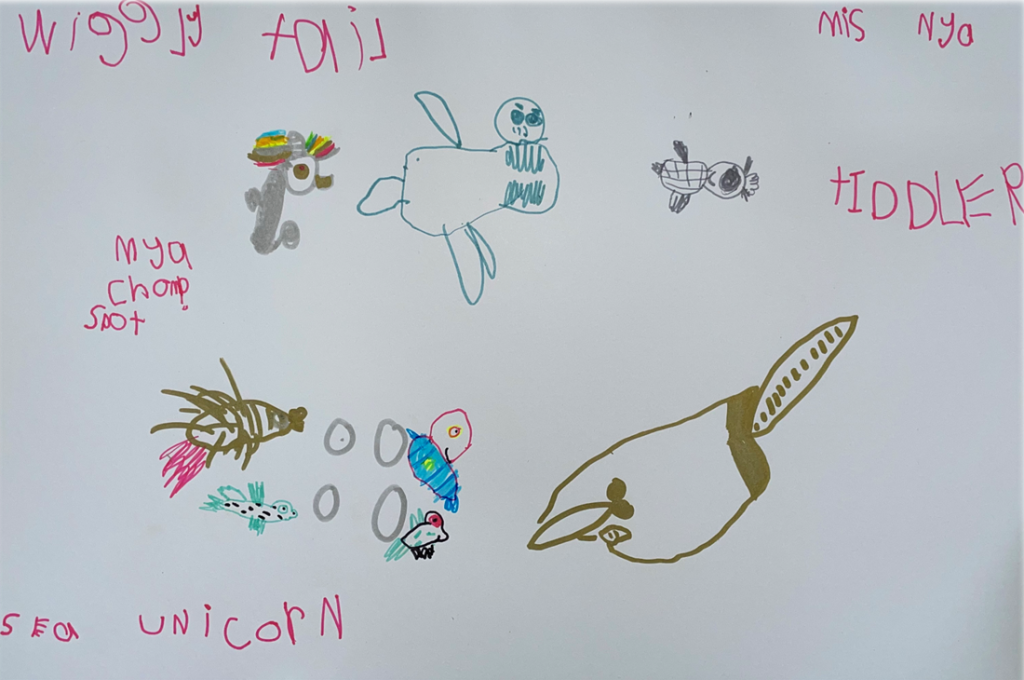

I let Clara choose if she wanted to draw the characters or write the story first. She was very excited about the sea-unicorn idea, and couldn’t wait to draw her, so she chose the first option. By continuing to provide the opportunity for Clara to make choices about the task, mutual respect and trust was built between the learner and facilitator (Peel & McLennan, 2019). Clara illustrated her version of some characters in the book, using the stimulus text as a direct reference for her stingray, while other characters were created from her imagination. She also gave the characters names and wrote them down. These skills fall under ACELT1580 (drawing representations of characters), ACELT1783 (using art to express personal responses to literature), and ACELY1651 (creating short texts) from the Australian Curriculum. Clara decided that one of Tiddler’s friends would be called Mya. She then wanted the teacher to be called Miss Nya. After thinking for a second, Clara said that she did not know how to spell ‘Nya’, but that it rhymed with Mya, so it must be spelt N-Y-A. While not falling under the scope of assessment for this task, “breaking words into onset and rime to learn how to spell words that share the same pattern” is part of content descriptor ACELA1438 (ACARA, n.d.).

Writing the Story

Once her characters had been created, it was time for Clara to develop the story. Throughout this discussion, I continuously asked open ended questions to encourage Clara to think more deeply about her choices (Walsh & Sattes, 2015). Once she was happy with her narrative, Clara dictated it for me to scribe, though she wanted to write her name and ‘The End’, asking me to help her spell ‘the’ (ACELA1817 – know how to write some familiar words) (ACARA, n.d.-a). She was then very excited to share her story with her mum (ACELA1435 – reading own texts aloud) (ACARA, n.d.).

ADDING IN DIGITAL COMPONENTS

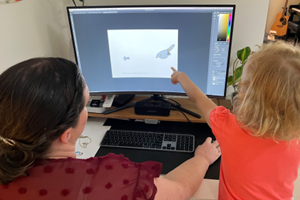

We used my iPhone to voice record Clara telling the story, then, while Clara had a snack and play break, I took photos of her illustrations, uploaded them to the computer, and used Photoshop to cut them out. When Clara came back, she was very excited to see her drawings on the computer. She had fun asking me to move her characters around the screen, eventually asking if she could have a go. After a quick lesson on how to use the mouse (something that she had never done before), Clara experimented with mouse movements to rotate, move, and change the size of her illustrations. This aligns with ACELA1433; ACELY1654, which both include using simple functions of the mouse and keyboard (ACARA, n.d.). As the New London Group suggested in their multiliteracies theory (1994), literacy pedagogy must now also include information and communication technologies (ICTs) (Cazden, et al., 1996). This will ensure that modern students are being prepared for the nature of contemporary everyday life (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009).

Clara was responsible for choosing all digital images used in the multimodal text. Although she did not use the search tool herself, she asked me to search for a particular image (such as jellyfish, sausages, etc) and then chose the one she wanted. Clara also chose the music used. Giving students these choices throughout learning experiences provokes feelings of empowerment, ownership, and positive feelings towards their work (Marshall, 2005). As we were looking through the images and music, we talked about how there were different ways to communicate the meaning of a story. These methods, called semiotic systems (Chandler, 2022), include the written and spoken language, images, and music that were chosen by Clara. We specifically discussed how music could be used to convey the ideas and emotions of a text and experimented with a few different compositions with different ‘feelings’ (sad, happy, silly, epic, etc.), and decided on one that gave the feeling of ‘fun’ (Taylor & Leung, 2019).

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Once the images and illustrations were finalised, it was time to construct our multimodal text in PowerPoint. With Clara’s direction and help, we placed her characters and chosen images in the scenes. Clara had chosen specific sea backgrounds for each of the scenes and was very particular about where each of them should go. It was wonderful watching her sense of pride and accomplishment grow as the choices she had made brought her story together (Marshall, 2005).

Outline of THE CHILD’S Learning

The Australian Curriculum outlines the following relevant Achievement Criteria for Foundation level students:

Receptive modes (listening, reading and viewing)

By the end of the Foundation year, students recall one or two events from texts with familiar topics. They recognise the letters of the English alphabet, in upper and lower case and know and use the most common sounds represented by most letters. They read high-frequency words and blend sounds orally to read consonant-vowel-consonant words. They use appropriate interaction skills to listen and respond to others in a familiar environment. They listen for rhyme, letter patterns and sounds in words.

Productive modes (speaking, writing and creating)

They retell events and experiences with peers and known adults. They identify and use rhyme, and orally blend and segment sounds in words. When writing, students use familiar words and phrases and images to convey ideas. Their writing shows evidence of letter and sound knowledge, beginning writing behaviours and experimentation with capital letters and full stops. They correctly form known upper- and lower-case letters.

To capture student learning from this experience, I created a criteria sheet based on the Australian Curriculum content descriptors chosen for this learning experience (ACARA, n.d.). I chose to assess this particular activity with a simple ‘yes’ and ‘no’ framework rather than using the official 5-point Prep Reporting Scale (Queensland Government, 2022).

Giving Clara as many choices as possible, and then actually honoring those choices, made this process very easy for us. Clara felt so much pride over the final product (even playing it for her class at school three times) because it was her work that was merely guided and scaffolded by me.

I would recommend not going into the experience with a set idea of what you want to achieve. By being flexible and able to adapt the plan on the spot, I believe Clara and I produced a much better final product than we would have if I had been stuck on my original plan.

I thoroughly enjoyed this process. Seeing the joy on Clara’s face as she watched the characters she had created ‘come to life’ on the computer was extremely rewarding.

Key Takeaways

- Give the children as many choices as possible throughout the process

- Follow the child’s lead on what and how they would like to explore the text/characters/topic

- Provide multiple modes of exposure to the stimulus text or topic

Above all – Make it fun!

The co-constructed multimodal text

References

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (n.d.). Australian Curriculum: English. https://australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/english/

Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., Gee, J., Kalantzis, M., Kress, G., Luke, A., Luke, C., Michaels, S., & Nakata, M. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Education Review 66(1), 60 – 92.

Chandler, D. (2022). Semiotics for beginners (4th ed.). Routledge.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (2009). “Multiliteracies”: New literacies, new Learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 4, 164-195.

Donaldson, J. (2016). Tiddler: The story-telling fish. Scholastic.

Fellowes, J., & Oakley, G. (2019). Language, literacy & early childhood education (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Marshall, M. (2005). Discipline without stress, punishments, or rewards. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 79(1), 51-54. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.79.1.51-58

Ness, M. (2017). Using informational and narrative picture walks to promote student-generated questions. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(5), 575-581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0817-7

Peel, K. L. & McLennan, B. (2019). Promoting pro-social behaviour. In D. Pendergast & K. Main (Eds.), Teaching primary years: Rethinking curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (pp. 372-399). Allen & Unwin.

Queensland Government (2022). P-12 Curriculum, assessment and reporting framework. Department of Education. https://education.qld.gov.au/curriculums/Documents/p-12-curriculum-assessment-reporting-framework.pdf

State of Victoria (2017). High impact teaching strategies: Excellence in teaching and learning. Department of Education and Training. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/practice/improve/Pages/hits.aspx

Taylor, S. V. & Leung, C. B. (2019). Multimodal literacy and social interaction: Young children’s literacy learning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00974-3

Walsh, J. A. & Sattes, B. D. (2015). Questioning for classroom discussion: Purposeful speaking, engaged listening, deep thinking. Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.