9 My Easter Adventure

Kerry Chant

For young children, learning experiences should be through a play -based approach and should connect to the Early Years Learning framework (EYLF, Department of Education, Employment and Work Relations [DEEWR], 2009) and working towards the Australian Curriculum: English foundation level (Australian Curriculum and Assessment Relations Authority [ACARA], 2018a).

CONNECTIONS TO THE EARLY YEARS LEARNING FRAMEWORK

Learning Outcome 1: Children have a strong sense of identity (DEEWR, 2009, p. 23)

Learning Outcome 4: Children are confident and involved learners” (DEEWR, 2009, p. 36)

Learning Outcome 5: Children are effective communicators

- Children interact verbally and non-verbally with others for a range of purposes (DEEWR, 2009, p. 42).

- Children engage with a range of texts and gain meaning from these texts

- begin to understand key literacy . . . concepts and processes, such as the sounds of language, letter-sound relationships, concepts of print and the ways that texts are structured (DEEWR, 2009, p. 44)

CONNECTIONS TO THE AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM

Foundation English

Literacy:

- ACELY1651 – Create short texts to explore, record and report ideas and events using familiar words and beginning writing knowledge

- ACELY1654 – Construct texts using software including word processing programs

Language:

- ACELA1433 – Understand concepts about print and screen, including how books, film and simple digital texts work, and know some features of print

- ACELA1437 – Understand the use of vocabulary in familiar contexts related to everyday experiences, personal interests and topics taught at school

Literature:

- ACELT1575 – Recognise that texts are created by authors who tell stories and share experiences that may be similar or different to students’ own experiences

(ACARA, 2018a)

According to Cope and Kalantzis (2018) all learning needs to be through design, so when planning the co-construction of the multimodal text there were four main considerations. The first was to ensure that the learning experience would be fun and engaging for the child (Lalu) because according to both the DEEWR (2009) and Fellowes and Oakley (2019), children learn through play. When play activities are incorporated into the learning experience, it harnesses a child’s natural disposition to explore which allows for expression of personality, builds curiosity, creativity, make connections between prior experiences and new learning and concepts and stimulates a sense of wellbeing (DEEWR, 2009, p. 10).

Play also helps create relationships with an educator through a shared enjoyment and this aligns with the social interactionist theory that suggest that learning happens through the interaction of others as well as the environment (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) so if the environment is happy and stimulating, this will maximise the learning potential and make a positive association with education (O’Connor, 2017) and develop a positive attitude towards literacy (Cartwright et al., 2016).

The second consideration is that the learning experience should incorporate Lalu’s interests because building on interest is more likely to engage the child into the learning (Oakley, 2006; Queensland Department of Education, 2016; DEEWR, 2009). It is known that Lalu likes animals, transport and being outdoors so this was incorporated into the learning experience. This aligns with Freebody and Luke’s (1992) “text participant practice” which is one of the roles that children need to fulfil to become an effective reader and writer (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

The third consideration was that the learning experience should be developmentally appropriate. This aligns to the cognitive developmental perspective which suggests that a child’s learning happens when a child is cognitively ready (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Lalu is 19 months old, and the developmental chart created by Jalongo (2014, as cited in Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p. 82) suggests that Lalu’s language would be at stage two of linguistic speech. This is characterised by ‘one-word utterances’ and a receptive vocabulary greater than an expressive vocabulary. Comprehension and syntactic knowledge is also increasing dramatically in this stage (Jalongo, 2014, as cited in Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Fellowes and Oakley (2019) and Head Zauche et al. (2017) attest that oral language experiences and social interactions are essential for developing language which contribute to literacy outcomes. Therefore, one of the goals of the learning experience was to increase Lalu’s vocabulary by introducing him to new words and encouraging him to develop his expressive and receptive vocabulary which, in turn, will support his future writing and reading development (ACARA, 2018a; DEEWR, 2009;Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Queensland Department of Education, 2019; Victoria State Government Department of Education, 2019).

Another goal was to encourage him to gain an understanding about print and knowledge about text purposes (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Scaffolding was implemented throughout the learning experience, using the gradual release of responsibility (GRR) model (Fisher & Frey, 2014) which aligns to the sociocultural perspective of literacy learning. The focussed/modelled and guided instruction stages of the model were mostly used due to Lalu’s capabilities in literacy and cognitive/physical development (Fisher & Frey, 2014).

Another factor to bear in mind is that according to Piaget’s cognitive developmental perspective (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019), Lalu is in the sensorimotor stage, moving towards the pre-operational stage of development where he is using his senses to interact with the environment (McCormick & Scherer, 2018) and not yet able to think at an abstract level (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Subsequently, the learning experience focussed on building vocabulary of concrete nouns rather than abstract nouns with the aim for him to have a partial knowledge of the words (Nagy & Scott, 2000, as cited in Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

In addition, at this developmental stage he has not developed the theory of mind (ToM) (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) so he may struggle to see other viewpoints which Piaget calls “egocentrism” (McCormick & Scherer, 2018). Considering this, a personal text of a recount (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p. 396) was created with Lalu since it would connect directly to him and his experience, making it more meaningful to him. Creating a text for authentic purposes is supported by the emergent theory of literacy learning (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p.7).

The final consideration, related to the previous one, is that Lalu is using his senses to interact with the environment at this developmental stage (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019), so he was given the opportunity to use several ways to create meaning. This idea came from the term ‘multiliteracies’ created by New London Group (1996) who argued there are many ways to do literacy including critical literacy and computer literacy (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). This is evident in Learning Outcome 5 of the EYLF (DEEWR, 2009, p.41) which has a broad definition of literacy. Literacy is also one of the General Capabilities in the Australian Curriculum so it should be incorporated in all areas of learning where possible (ACARA, 2018b).

There are various ways that meaning is communicated, known as semiotic systems (Chandler, 2017), and these systems, according to Bull and Anstey (2010), are linguistic, audio, visual, gestural, and spatial. Within each system there are signs within them which add another depth to the meaning (refer to slide). Cope and Kalantzis (2009, p. 363) suggest that children have natural “synaesthetic capacities” which means they are creating the same meaning across the semiotic systems. However, some learners may be more comfortable in one mode of meaning-making than another (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009; Kalantzis & Cope, 2018) so children should be given opportunities to make their own meaning in various modes using multiple semiotic systems. This aligns to the sociocultural perspective of literacy learning (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) and it is also reflected in the EYLF’s (DEEWR, 2009) broad definition of literacy.

Using THE e-LEA Approach

From reflecting on the four considerations as previously discussed, an e-LEA Approach (Oakley, 2008) was considered to be the best option as it could incorporate play, Lalu’s interests, it could be tailored to Lalu’s age and capabilities and, most importantly, it could incorporate multiliteracy theory (New London Group, 1996) and the semiotic systems. The e- LEA Approach (Oakley, 2008) would also help build Lalu’s semantic knowledge and increase his vocabulary repertoire because it would expose him to words of different forms (nouns, adjectives, verbs and adverbs) (Queensland Department of Education, 2019). Additionally, pragmatic knowledge would be built on as he would be interacting with people and being exposed to different situations (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

PRIOR TO THE e-LEA

Prior to the multisensory experience, a modelled text was used to build his vocabulary and help Lalu connect to prior knowledge (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) and to set the scene or “field” for the experience” (Victoria State Government Department of Education, 2019). The book was Spot & Say Farm (Pat-a-Cake, 2019) which uses the game ‘eye spy’. This was chosen not only to help him with semantic and phonological awareness but primarily as it would help him to make meaning as a ‘text participant’ (Luke & Freebody, 1999) using multiple semiotic systems including the visual and linguistic systems, which Landes (1987, as cited in Taylor and Leung, 2020, p. 3) stated give picture books a “high semiotic capacity”. The book (Pat-a-Cake, 2019) also has flaps providing a tactile element to meaning-making as suggested by Cope and Kalantzis (2009).

In addition, Lalu held the book and turned the pages utlising another tactile element. A “hands-on approach” in book reading helps build a knowledge of print to promote a good literacy foundation ready for pre-school and school literacy practices (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p. 208). This represents the ‘Code breaker’ element in Luke and Freebody’s (1999) Four resource model.

The book was read in a dialogic way which is reading led by the child’s interest (DEEWR, 2009; Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Head Zauche et al., 2017). It was read using the “interactive read-aloud” approach where questions were asked during the reading (Fisher et al., 2004, as cited in Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p. 292) to further increase vocabulary. Furthermore, Churchill et al. (2019) note that questioning is also useful for stimulating a child’s interest.

Taylor and Leung (2020) suggested that by reading the book out loud it provides another dimension to the meaning-making, not only just as a linguistic mode, but using auditory cues such as prosody (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Additionally, Cope and Kalantzis (2009, p. 422) note that there is a spatial element to reading out loud as well because meaning can be influenced by the proximity of the speaker. For instance, Lalu was read to by lap reading (close proximity). If I were to read further away, he may have inferred a lower importance of reading (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009). This learning experience aligned to both the sociocultural literacy theory as an educator scaffolded the learning (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019 p. 8) as well as the emergent theory as a whole text was used in the context of learning (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p.7). Cambourne (1988, as cited in Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p. 7) suggested that being immersed in and being shown demonstrations of literacy is important in literacy and language acquisition, as demonstrated in this step.

Step 1: The multisensory experience

The e-LEA Approach (Oakley, 2008) aligns to the sociocultural perspective of literacy as the learner is immersed into a social and cultural environment (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Seven steps are involved in the e-LEA approach (Oakley, 2008), the first of which is a multisensory experience. Lalu’s experience was meeting his family overseas and engaging with them in various activities aligned to his interests.

Photographs and videos were taken to capture the experience. This experience connects to the Australian Curriculum content descriptor for foundation level ACELA 1437, “Understanding the use of vocabulary in familiar contexts related to everyday experiences” (ACARA, 2018a). Lalu chose the pictures that he wanted for creating the multimodal text.

Step 2: Elaboration of the experience

The second step was elaboration of the experience where the photographs and videos taken on the multisensory experience were viewed and discussed to help him with his recall of the experience. Level one, selecting questions (Blank et al., 1978) were used such as, “Where was this taken?”, “Who is that in the photo?”, “What comes next” etc. to help elicit responses. Answers were given using the modelling phase in the GRR (Fisher & Frey, 2014).

Toys were given to Lalu to help him recreate the experience in his own way using socio-dramatic play and music from his experience (song played from the toy car) was used to help him in recalling the experience (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Jäncke, 2008). These were used to help him make his own meaning using the five semiotic systems (visual, linguistic, gestural, audio and spatial) (Bull & Anstey, 2010; Taylor & Leung, 2019).

Step 3: Detailed discussion and retelling

In step three of the e- LEA (Oakley, 2008), Lalu was helped to create an oral retell of the experience by using scaffolding. This is when help is given to extend a child’s learning in what Vygotsky called the ‘zone of proximal development’ (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Scaffolding was done using questioning to elicit expressive vocabulary from Lalu. Questioning used Blank et al.’s (1978) questioning framework. I started with a level one matching question, “what is in this photograph?” and when he produced a response, a level two selective analysis question was asked such as, “what colour is the canoe?” Fellowes and Oakley (2019) refer to these questions as literal visual comprehension questions which they state are the first steps to critical literacy.

Transcript: “Picture.” “Hat.” “A hat.”

Higher cognitive questioning was used in Blank’s framework with modelled answers where necessary. The “thinking aloud technique” (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) was used whereby I explained my reasoning for the answer given and the thinking processes behind it saying, for example, “I think in this picture we are at the farm because I can see lots of animals”. This type of questioning helps to develop critical literacy, and sustained shared conversations extend thinking (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Sraj-Blatchford et al., 2002).

Juxtaposition was used to compare photographs (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019), for example, comparing the clothes Lalu wore in England to those worn in Australia. This encouraged him to notice elements in the photograph. Pointing out clothing and other details in photographs helps build critical literacy which develops the ‘text analyst’ component of the Four resource model (Luke & Freebody, 1999).

Step 4: Producing the illustrations

In step four, Lalu chose his favourite photograph from the experience, and a model of the experience was co-constructed using the GRR model (Fisher & Frey, 2014) first through modelling and then by guided instruction. In making the model, there were parts where Lalu could work up to the independence step in the GRR model (Fisher & Frey, 2014), for example, colouring in. The emergent literacy theory suggests that early scribbles with writing materials, like colouring pencils, is seen as emerging writing and reading skills (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

When co-creating the model with Lalu, there were opportunities to use more vocabulary with the use of adjectives for colours, shapes, and textures, as well as prepositions like “on” “over” etc, increasing Lalu’s semantic knowledge. This is supported by Fellowes and Oakley (2019, p. 97) who suggest that “hands-on” interaction with a variety of materials should be encouraged to increase expressive and receptive language use. Christ and Chiu (2018, as cited in Fellowes and Oakley, 2019) wrote that vocabulary learning will be incidental if there is a chance to use language in authentic contexts. This aligns to the emergent theory of language and literacy learning (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Furthermore, according to the National Association for the Education of Young Children (1998, as cited in Fellowes and Oakley (2019, pp. 384-385), Lalu is moving towards the beginning phase of writing development where a good hand-eye coordination is needed, and co-constructing the model assists with this development.

When creating the model, meaning-making was extended further by using the nursery rhyme “row row row your boat” with the gestures. Education at Illinois (2019) suggested that different modes of learning should be harnessed in producing meaning (multimodality). In addition, Fellowes & Oakley (2019) suggested that toddlers should be involved in song. In addition, gestures are thought to be the first signs of language according to Vygotsky (1978, as cited in Taylor and Leung, 2020). Lalu used his own previous knowledge to make connections of the model canoe to the song. I reinforced this by joining in with the song which aligns to the behaviourist theory of literacy development (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

Step 5: Eliciting the oral story

Outline of Key Strategies

- Modelled e-text

- Think aloud strategy (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

- Developing concept of print (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

- Purpose and audience of the text made explicit (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

- Structural features of a personal recount identified (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

- Use of questioning (Churchill et al., 2019; Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

- Positive reinforcement

- Connections made to oral and written language (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

In step five, a modelled text was used to intentionally teach Lalu the structural features of a personal recount (DEEWR, 2009; Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) so that he could be exposed to relating them to his own text. This aligns to the text user aspect of the Four resource model (Freebody & Luke, 1999). Modelling was done using the “think aloud strategy” (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) and using questioning (Churchill et al., 2019; Victoria State Government Department of Education, 2019). This helped him tell me what was in the pictures or use gestures to show me where he could see certain images referred to e.g., Which person in the picture do you think is the daddy?”. Attention was drawn to pronouns and past tense verbs and words to show time order used in the modelled text and who we think the audience might be. Following this, it was explained to Lalu that we were going to write his story like the modelled text, and that we are going to share the story with his dad and other family members. Fellowes & Oakley (2019) noted the importance of teaching a child the audience for a text and the purpose for the text.

The recount of the story was elicited from Lalu verbally with the aid of sequencing the photos from the experience to help him remember the story and labels that were used on the pictures. Questioning was used in the same manner as in Step 3 to help elicit responses and verbal praise was given when he used expressive vocabulary or gestures such as pointing. Praising and reinforcing behaviour is concurrent with the behaviourist theory of literacy learning, and Hattie and Timperley (2007) say feedback is critical for developing literacy.

Lalu’s words were recorded using the computer which consisted of one words or two words. I modelled some sentences using the words he spoke and recorded those as well. The reason for this was twofold, the first reason was to help him connect to the fact that oral language could be written down and the second reason was that he could hear the sentences with correct form (phonology, morphology and syntax) (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

Step 6: Scribing the story

Outline of Key Strategies

- Modelling handwriting

- Use of handwriting line guide (West, 2022)

- “Think aloud strategy “when writing (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

- Writing materials for Lalu

- Labels on photographs

- Concept of typing

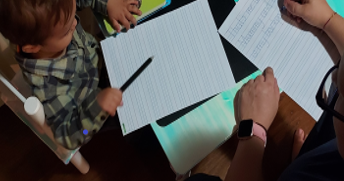

In step 6 of the e-LEA strategy, the recordings were listened to, and I wrote them down on a paper that contained handwriting guidelines (West, 2022). Modelling of handwriting was done through “thinking out loud” (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019), explaining each part of the letter formation, such as touching the top line (West, 2008). Care was taken to follow the correct hold for writing as suggested by Speech & Language Development Australia [SALDA] (n.d) and posture as recommended by Qualia (n.d). Lalu had a selection of writing implements and type of paper as suggested by Fellowes and Oakley (2019) so he could make his own writing attempts and develop his fine motor skills (SALDA, n.d). Thinking was verbalised for leaving a space between each word and for concepts of print such as writing from left to right (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; CECE Early Childhood Videos at Eastern CT State U, 2009). The labelled pictures were used to reinforce the idea that the words related to the photographs from the experience (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Only one sentence was modelled in the handwriting due to Lalu’s short attention span and the aim was only to introduce him to the concept of handwriting.

Following the handwriting modelling, the sentence and the other recorded words and sentences were typed on the computer.

Step 7: Re-reading the story

Lalu read chorally as the slides of the PowerPoint presentation were moved. Time was given for him to respond. Churchill et al. (2019) noted the importance of waiting response time in eliciting responses.

In the final step the recount was re-read and shared with Lalu’s dad.

Using Information Communication Technology (ICT)

Information Communication Technology (ICT) was used in many ways during the teaching episodes. This was to prepare Lalu for the twenty-first century as we live in a digital world (Taylor & Leung, 2019) and it also built on his prior experiences with ICT and to help him understand the different modes of meaning involved in a multimodal text. As Cope & Kalantzis (2009) wrote, the modes of meaning used to be separate but in the modern world they are now combined so it is important to teach these meanings. In the created multimodal text, the words and pictures showed symmetrical meaning (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006, as cited in Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). This was so that Lalu could connect the pictures to the words and help promote what Cope and Kalantzis (2009) refer to as synaesthesia.

There are connections to ICT in both the EYLF (DEEWR, 2009) and in the Australian curriculum where ICT is considered a General Capability (ACARA, 2018c).

In teaching visual literacy, “verbal mapping” (Otto, 2017) was used whereby I would verbally explain moving images and cropping. Through modelling, I would draw Lalu’s attention to comparing images (juxtaposition), by saying ”Look! There’s you. Let’s make your picture bigger”, or when moving images, “ Let’s put this here because we can see the image clearer”. This relates to both visual and spatial semiotic systems in meaning-making (Bull & Anstey, 2010) and connects to the “text analyst” role (Luke & Freebody, 1999).

Audio clips and video were added to the multimodal text to add more dimensions of meaning-making. Lalu particularly liked hearing his voice in the presentation so it was repeated many times. It was reinforced that it was “his book for sharing his story of what we did over Easter when we met Nanna and Grandad”.

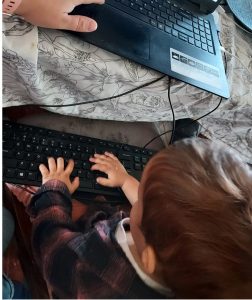

Lalu was given a separate keyboard to play on during the modelling of typing and he used the mouse in the guided instruction phase of the GRR (Fisher & Frey 2014) when viewing the e-book model (Unite for Literacy, 2014) and for creating components of the multimodal text.

Other Resources

- Word wall

- Paint

- Tactile art materials

- Pens/ pencils

- Playdough

- Recycled materials

- Natural materials

A range of materials were used in learning experience. A word wall was created with concrete nouns which were classified under three headings: family, transport and animals. This was to expose Lalu to the fact that words can be classified into groups and introduce some metalanguage (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p.420).

Some of the materials used were recycled items such as an egg box which connects with the “sustainability” cross-curriculum priority in the Australian curriculum (ACARA, 2018d). Different tactile art materials were used to add another dimension of meaning-making and there were a range of writing implements available for Lalu to use. Fellowes and Oakley (2019, p. 402) suggest that there should be a range of materials provided for literacy practices.

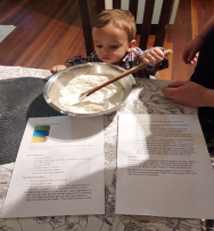

Playdough was used to help build on Lalu’s fine and gross motor skills and was made from a recipe. This provided a teachable moment to show Lalu the purpose of a recipe or procedural text in creating the playdough. Lalu was involved in the mixing process of the flour, salt and water.

Playdough was used to help build on Lalu’s fine and gross motor skills and was made from a recipe. This provided a teachable moment to show Lalu the purpose of a recipe or procedural text in creating the playdough. Lalu was involved in the mixing process of the flour, salt and water.

Another teachable moment (DEEWR, 2009) was when his cousin gave him a personal card. It enabled me to teach him that it was for him and its purpose was to welcome him to their home. Fisher and Frey (2018, p. 89) suggested that there should opportunities for print exposure as reading volume is associated with better literacy outcomes.

Lalu collected rocks that he used for his model. This connected to his interest in the outdoors and in rock collecting. The EYLF (DEEWR, 2009) encourages outdoor activities.

Following on from the previous nursery rhyme ‘Row row row your boat’ as previously discussed, an additional song was incorporated. The decision was made because Lalu had shown interest in using a song with actions and nursery rhymes help build phonological awareness (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). The second song was ‘5 little ducks’. Finger puppets were co-created using the remaining half of the egg carton. The song was sung with the duck puppets and each one was removed in sync with the lyrics of the song. This gave multiple modes for meaning-making as well as connecting to numeracy which is another cross-curriculum priority.

Outline of the Child’s Learning

Affective factors observed during the learning experience:

-

- Lalu showed an interest in the learning experience.

- Lalu showed a happy and relaxed disposition whilst engaging in the activities (Cunningham & Moore, 2004, as cited in Fellowes & Oakley).

- Lalu chose to engage in another book (independently) after using modelled text (pictured below). Text was a book about farms reaffirming his interest.

- He appeared to be excited in showing his dad the multimodal text.

Lalu’s learning connected to the EYLF (DEEWR, 2009) in the following ways:

- “Children interact verbally and non-verbally for a range of purposes” (DEEWR, 2009, p. 42). This was developed when gestures and oral responses were encouraged with Lalu.

- “Children engage with a range of texts and gain meaning from these texts” (DEEWR, 2009, p. 42). This was met through engaging with a recipe, a personal card and through nursery rhyme and song.

- “Children express ideas and make meaning using a range of media” (DEEWR, 2009, p. 42). This was met when Lalu used various materials to create a model of a canoe from the photograph and in performing the nursery rhyme ‘Row row row your boat’.

- “Children begin to understand how symbols and pattern systems work” (DEEWR, 2009, p. 42). This was met when Australian English language was modelled in the teaching experience both in reading aloud and in handwriting and typing modelling. Also when viewing a recipe and editing photographs through cropping etc.

- “Children use information and communication technologies to access information, investigate ideas and represent thinking” (DEEWR, 2009, p. 42). This was met through recording Lalu’s voice, creating the multimodal powerpoint using the computer, taking photographs and videos with a smartphone.

Lalu’s learning also connected with content in the Australian Curriculum Foundation year (ACARA, 2018) and the highlighting shows where this was working towards meeting the achievement standard for the end of Foundation year (ACARA, 2018a). I had only aimed to connect to a few content descriptors, but I kept finding teachable moments as the EYLF (DEEWR, 2009) suggests.

The assessment of Lalu’s learning was formative. I observed Lalu and tailored the experience towards his interests, gathering data over a short period of time. Learning may not occur in the same way for all children and children’s linguistic development may seem to go backwards when they are experimenting with language. Therefore, one sample of work would probably not be a true reflection of Lalu’s abilities.

Furthermore, the EYLF (DEEWR, 2009) noted that a child’s interest may change so it is important to keep reflecting on teaching practices through child observations, and families should be engaged with regularly to help plan effective teaching programs (DEEWR, 2009). As noted by Churchill et al. (2019) effective teachers are always trying to improve their practice and they never arrive at being the perfect teacher as there is always something that can be improved or needs adjusting to suit the various needs of the learner.

Another consideration was that Lalu could not fully verbally articulate how he felt. It was my own assumptions based on the fact that he seemed happy and engaged in the activities. This is one of the affective factors of literacy as described by Cunningham and Moore (2004, as cited by Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

Connecting to the child’s prior knowledge in nursery rhymes promoted interest and motivation in the learning. Providing multiple means for engagement such as using songs and art materials and also connecting to family and a recent experience seemed particularly useful in engaging the child. Knowing that they have helped to make the multimodal text was also rewarding for the child.

Readers should avoid trying to cover too much in a session, especially when working with younger children as they tend to have short attention spans. Readers should be open to trying multiple ways to engage the child and should monitor the child to see if they are still engaged and should consider allowing the child to lead the learning.

Co-creating a multimodal text was stimulating for the child and I really enjoyed the project. I found that there were many teachable moments that could be utilised in the process of creating the multimodal text. After the planning process, it was relatively simple to co-create the multimodal text with the child.

The Co-Constructed Multimodal Text

References

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2018a). Australian Curriculum English: Foundation Level. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/english/?year=11574&strand=Language&strand=Literature&strand=Literacy&capability=ignore&capability=Literacy&capability=Numeracy&capability=Information+and+Communication+Technology+%28ICT%29+Capability&capability=Critical+and+Creative+Thinking&capability=Personal+and+Social+Capability&capability=Ethical+Understanding&capability=Intercultural+Understanding&priority=ignore&priority=Aboriginal+and+Torres+Strait+Islander+Histories+and+Cultures&priority=Asia+and+Australia%E2%80%99s+Engagement+with+Asia&priority=Sustainability&elaborations=true&elaborations=false&scotterms=false&isFirstPageLoad=false

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2018b). F-10 curriculum, general capabilities, literacy. https://australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/literacy/

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2018c). F-10 curriculum, general capabilities, information communication technology (ICT) capability. https://australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10- curriculum/general- capabilities/information- and-communication-technology-ict-capability/

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2018d). F-10 curriculum, Cross curriculum priorities. https://australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/cross-curriculum-priorities/

Blank, M., Rose, S. & Berlin, L. (1978). The language of learning: The preschool years. Grune & Stratton.

Bull, G. & Anstey, M. (2010). Evolving pedagogies: Reading and writing in a multimodal world. Education Services Australia.

Cartwright, K., Marshall, T. & Wray, E. (2016). A longitudinal study of the role of reading motivation in primary students’ reading comprehension: Implications for a less simple view of reading. Reading Psychology, 37(1), 55-91. http://doi.org10.1080/02702711.2014.991481

CECE Early Childhood Videos at Eastern CT State U. (2009). Five predictors of early literacy [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HqImgAd3vyg

Chandler, D. (2007). Semiotics: The basics (2nd ed). Routledge.

Churchill, R., Godinho, S., Johnson, N., Keddie, A., Letts, W., Lowe, K. Mackay, J., McGill, M., Moss, J., Nagel, M., Shaw, K. & Rogers, J. (2019). Teaching: Making a difference. John Wiley & Sons Australia.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (2009). A grammar of multimodality. The International Journal of Learning, 16(2), 361-425.

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. (2009). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia. Australian Government. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-02/belonging_being_and_becoming_the_early_years_learning_framework_for_australia.pdf

Education at Illinois (2019). 1. Background to the Multiliteracies Project [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVRehngLMqs

Fellowes, J., & Oakley, G. (2019). Language, literacy, and early childhood education (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2014). Better learning through structured teaching: A framework for gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2018). Raising reading volume through access, choice, discussion, and book talks. The Reading Teacher 72(1) 89-97.

Freebody, P. & Luke, A. (1992). A socio-culture approach: Resourcing four roles as a literacy learner. In A. J. Watson & A. M. Badenhop (eds). Prevention of reading failure. Ashton Scholastic.

Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112.

Head Zauche, L., Mahoney, A., Thul, T., Zauche, M., Weldon, A. & Stapel-Wax, J. (2017). The power of language nutrition for children’s brain development, health, and future academic achievement. Journal of Pediatric Healthcare, 31(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.01.007

Jäncke L. (2008). Music, memory and emotion. Journal of Biology, 7(6), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/jbiol82

Kalantzis, M. & Cope, B. (2018). Multiliteracies and learning by design [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JNrQnI7oUk

Kids Activities.com. (2022). Playdough recipe. https://kidsactivitiesblog.com/206/play-dough/

Luke, A. & Freebody, P. (1999). A map of possible practices: Further notes on the Four resource model. Practically Primary, 4(2), 5-8.

McCormick, C. B., & Scherer, D. G. (2018). Child and adolescent development for educators (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

O’ Brien. (2020). Creating multimedia texts. https://creatingmultimodaltexts.com/

O’Connor, D. (2017). Loving Learning: The value of play within contemporary primary school pedagogy. In S. Lynch, D. Pike & c. Beckett (eds), Multidisciplinary perspectives on ply from birth and beyond (pp. 93-107). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2643-0_6

Oakley, G. (2006). From theory to practice: Motivating children to engage in reading. Practically Primary, 11(1), 18-22.

Otto, B. (2017). Language development in early childhood (5th ed). Pearson Education.

Pat-a-Cake. (2019). Spot and say farm. Hodder & Stoughton.

Qualia. (n.d). Are you holding your pen correctly? http://qualiatherapy.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Qualia-hand-out-Pencil-Grasp.pdf

Queensland Department of Education. (2016). Being a communicator-literacy strategies in Indigenous early childhood education [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bIWuvkh1I74

Queensland Department of Education. (2019). 5 of 25 – Vocabulary. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0bzSmPN8M5Y

Speech & Language Development Australia. (n.d). Handwriting-developing pencil skills and an efficient grasp.

Sraj-Blatchford, I., Sylva, K., Muttock, S., Gilden, R. & Bell, D. (2002). Researching effective pedagogy in the early years. Department for Education and Skills Research. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/4650/

Taylor, S. V., & Leung, C. B. (2020). Multimodal literacy and social interaction: Young children’s literacy learning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(1), 1-10. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10643-019-00974-0

Unite for Literacy. (2014). Family time [E-book]. https://www.uniteforliteracy.com/unite/family/book?BookId=1702

Victoria State Government Department of Education. (2019). Literacy teaching tool kit: Teaching and learning cycle: Reading and writing connections. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/readingviewing/Pages/teachingpraccycle.aspx

West, B. (2008). How to teach handwriting [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZrdC3u6LiWc

West, B. (2022). Resources for handwriting. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1j4ySFbZhp1J1kplKr8k8wtG1m65r1AnK