3 Humpback Whales

Rhiannon Davis

Magnus is aged 5 and he was in the first year of school, Foundation year level, when he created this text. He chose to create an informative text, illustrated with images he drew and those sourced from online creative commons. He narrated the text and we co-constructed it in Microsoft PowerPoint.

CONNECTIONS TO THE AUSTRLALIAN CURRICULUM

The learning intentions for the co-constructed text match select content descriptors of the Australian Curriculum: English Literacy and Language Strands for Foundation Year, and are informed by literacy as a general capability (ACARA, 2018a). The Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF) (DEEWR, 2009), was also referred to; specifically Outcome 5: Children are Effective Communicators.

Language:

- ACELA1430 – Understand that texts can take many forms, can be very short (for example an exit sign) or quite long (for example an information book or a film) and that stories and informative texts have different purposes

- ACELA1431 – Understand that some language in written texts is unlike everyday spoken language

- ACELA1432 – Understand that punctuation is a feature of written text different from letters; recognise how capital letters are used for names, and that capital letters and full stops signal the beginning and end of sentences

- ACELA1433 – Understand concepts about print and screen, including how books, film and simple digital texts work, and know some features of print, for example directionality

- ACELA1786 – Explore the different contribution of words and images to meaning in stories and informative texts

Literacy:

- ACELY1651 – Create short texts to explore, record and report ideas and events using familiar words and beginning writing knowledge.

ACELY1652 – Participate in shared editing of students’ own texts for meaning, spelling, capital letters and full stops

ACELY1653 – Produce some lower case and upper case letters using learned letter formations

ACELY1654 – Construct texts using software including word processing programs

CONNECTIONS TO THE EARLY YEARS LEARNING FRAMEWORK

The Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF) (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations [DEEWR], 2009), was also referred to; specifically Outcome 5: Children are Effective Communicators.

- Children interact verbally and non-verbally with others for a range of purposes

- Children engage with a range of texts and gain meaning from these texts

- Children express ideas and make meaning using a range of media

- Children begin to understand how symbols and pattern systems work

- Children use information and communication technologies to access information, investigate ideas and represent their thinking

Planning

Early reading and writing development

Considering early reading and writing development, the whole language approach, a component of emergent theory, was implemented. This was achieved by engaging with the mentor texts for the authentic purpose of finding facts to include in the report and demonstrating the language features of an informative text. The mentor texts we used included 1000 questions and answers about Australian wildlife (Parish, 2002), Question and answer encyclopedia (1998), First field guide to Australian mammals (Slater, 1997), The snail and the whale (Donaldson & Scheffler, 2003), and The whales’ song (Sheldon, 1993). Reading knowledge was supported throughout by pausing to consider letter-sound relationships, punctuation, and text directionality (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) as per ACELA1432 and ACELA1433 (ACARA, 2018). In alignment with ACELA1430 and ACELA1431 (ACARA, 2018) Magnus and I discussed the present tense, descriptive subject-specific language, and language features such as verbs, nouns and pronouns as typical of report writing (Department of Education and Training Victoria, 2019; Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

Selection and use of other resources

After Magnus had decided the multimodal text would be centred on humpback whales, both informative and narrative stimuli were engaged with to allow for comparison between varying text forms, as per ACELA1430 (ACARA, 2018). Magnus was then given the opportunity to choose the type of multimodal text to be co-constructed, to increase his motivation for engagement with the project (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019; Pappamihiel & Knight, 2016), while contextualising the learning to a topic that was of interest to him (Peel & McLennan, 2019).

Selection of ICT

I chose to use Microsoft PowerPoint to co-construct the text, and explained to Magnus that we would be presenting the multimodal text as a slide show which he would narrate. In preparation, I took note of the ICT General Capability and ACELY1654 (ACARA, 2018) to ensure the appropriateness of teaching processes.

Teaching Strategies and Processes

Reading Strategies

- Scaffolding through GRR

- Modelled reading

- Shared reading

- Vygotsky’s ZPD (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

- Supporting the development of the five pillars of effective reading (Phillips et al., 2018)

Writing Strategies

- Scaffolding through GRR

- Modelled writing

- Interactive writing

- Vygotsky’s ZPD (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019)

During the co-construction, scaffolding was used through the gradual release of responsibility (GRR) (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). This process was initially achieved through modelled reading as I read the stimulus texts to Magnus. Some shared reading was also conducted as I paused to allow him to read familiar words, or sound out simple, three letter words.

Similarly, during the writing process, GRR was once again implemented through modelled writing, followed by interactive writing (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) where we scribed the facts that Magnus wished to include in the multimodal text. We then worked collaboratively to reread the developed text to ensure it communicated what Magnus wanted to say, contained language features of informative texts and was factually accurate, in alignment with ACELY1651, ACELY1652, ACELY1653 (ACARA, 2018).

The above modelled reading progressing to shared reading, in an environment scaffolded through the use of GRR, aligns with socio-cultural theory, specifically Vygotsky’s notion of increasing a child’s zone of proximal development (ZPD) (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) to support and develop the five pillars of effective reading (Phillips et al., 2018). Similarly, modelled, interactive, then shared writing, can gradually progress to guided then independent writing through the implementation of GRR where the more knowledgeable adult supports the child to increase their ZPD (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

Learning through play

- Making connections between past experiences and new learning;

- Child-initiated play to enhance learning (DEEWR, 2009).

The EYLF (DEEWR, 2009) notes that learning through play enables children to make connections between past experiences and new learning. Similarly, Parker and Thomsen (2019) note that there is strong evidence that learning through play has a positive impact on learning. During a break in co-constructing the text, Magnus initiated a Lego play session in which he created an underwater scene depicting one whale singing to another, imitating what he had learnt from the mentor text. This demonstrated how child-initiated play can enhance and promote learning (DEEWR, 2009).

Use of ICT for Enhancing Curriculum Learning

ICT

- Further investigation of topic;

- Communicate ideas (DEEWR, 2009);

- Word processing capabilities;

- ICT as a General Capability (ACARA, 2018a).

e-LEA

- Multisensory experience;

- Elaboration, discussion and retelling;

- Producing the illustrations;

- Recording the oral story;

- Scribing the story;

- Rereading the story (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

To meet ACELY1654 and ACELA1433 (ACARA, 2018) and EYLF Outcome 5 (DEEWR, 2009), ICT was utilised by allowing Magnus to type some text for the co-construction. Further exposure to ICT was achieved by recording Magnus’s narration and listening to the recorded audio for accuracy.

As per the EYLF (DEEWR, 2009), the use of ICT was implemented to further investigate the topic of humpback whales and used to communicate Magnus’s ideas. This was achieved through utilising elements of the electronic language experience approach (e-LEA) (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

Initially, Magnus engaged in the multisensory experience (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) of listening to recorded humpback whale songs and watching videos of humpback whales in their natural habitat. This experience was verbally elaborated upon and inspired Magnus to create illustrations that would later be photographed and added digitally into the multimodal text. An ‘oral story’ (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019, p. 551) was recorded, then scribed into the co-construction. The e-LEA, which was heavily scaffolded (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019), integrated reading, writing, listening and speaking to build upon Magnus’s existing knowledge and vocabulary surrounding humpback whales (Nessel & Dixon, 2008; Pappamihiel & Knight, 2016). It also provided an opportunity for Magnus to build ICT competency and critical thinking skills while meeting curriculum requirements through authentic interactions with meaning, essential to language development (Pappamihiel & Knight, 2016).

Multiliteracy Theory

- The changing nature of communication requires a change in teaching approaches (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000 as cited in Baguley et al., 2010).

- The digitisation of the multimodal text adheres to multiliteracies theory.

- Multimodal layers of the environment used to build upon prior knowledge (Baguley et al., 2010).

Given the complex nature of multimodal texts, children need to be explicitly taught how to comprehend and compose them in order to become multiliterate (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019).

When considering the implementation of multiliteracies theory, Cope and Kalantzis (2000, as cited in Baguley et al., 2010) note that the changing nature of communication requires adaptations in the ways literacies are taught and defined. The digitisation of the co-created text adheres to multiliteracy theory by enabling the text to be presented in a multimodal format, incorporating aural and oral elements in addition to the literary text (Baguley et al., 2010).

In alignment with multiliteracy theory, various media were combined to present information to Magnus to assist in the co-creation of the multimodal text. This assisted him in comprehending and contextualising the information that he was exposed to by utilising the multimodal layers of his environment to build upon prior knowledge (Baguley et al., 2010).

During the co-construction, the four dimensions of the Multiliteracies Map (DECS, 2010, as cited in Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) were considered. The functional dimension considered Magnus’s knowledge of ICT such as competently using the mouse and recognising computer icons. The meaning-making dimension was implemented when discussing the informative text language features witnessed in the mentor texts. The critical dimension was employed when Magnus came across conflicting information within the mentor texts and was required to seek clarification through further research. Finally, the transformative dimension was demonstrated when Magnus initiated a Lego play session in which he transferred new knowledge into a Lego construction.

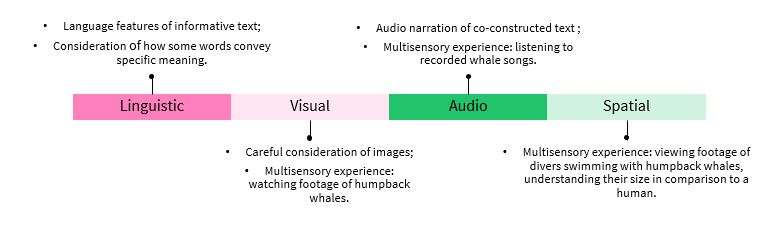

Semiotic Systems

The proliferation of ICT in classrooms has facilitated a shift to a multimodal semiotic literacy system, incorporating linguistic, visual, audio, spatial and gestural systems (Bull & Anstey, 2018; Iyer & Luke, 2010). Bull and Anstey (2018) posit that multimodal texts convey meaning by drawing on several semiotic systems. The co-constructed text encompassed all the semiotic systems, excepting gestural elements.

The linguistic system was implemented through the language features of informative writing in the scribed text, considering the impact of specific words as per ACELA1786 (ACARA, 2018). The visual semiotic system was utilised through the careful consideration of images to be included in the co-construction and how they would scaffold the interpretation of the message (Pappamihiel & Knight, 2016). The audio semiotic system was employed during the multisensory experience, implementing audio narration into the multimodal text and including recorded whale song within the co-construction. Finally, the spatial semiotic system was adhered to during the multisensory experience when Magnus saw a video of scuba divers swimming among whales, demonstrating and contextualising to him the enormousness of a whale in comparison to a human. This process aligned with ACELA1786 (ACARA, 2018), considering how words and images contribute meaning to informative texts.

Outline of the child’s learning

Throughout the co-construction, Magnus learnt to create a short, informative multimodal text using ICT. He gained an understanding of language features typical to informative texts and the importance of multiliteracy theory and the semiotic systems when making meaning through the inclusion of visual and aural aids. He also learnt the importance of rereading text and relistening to audio for editing purposes.

Formative assessment

The EYLF (DEEWR, 2009) states that including children in the assessment process allows them to better understand themselves as learners and how they learn best. Therefore, as a method of formative assessment, Magnus was asked to complete a self-assessment checklist (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) to determine which areas he had a firm understanding of, and which learning intentions needed further focus. The checklist, based on the abovementioned content descriptors (ACARA, 2018) that informed the learning intentions, posed a series of simple questions, delivered through a writing conference (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019). Given the text was co-constructed through shared and interactive writing, the checklist questions were posed in first person plural.

Summative assessment

As with the formative assessment, a checklist (Fellowes & Oakley, 2019) was once again used for summative assessment, however, it was completed without input from Magnus. The checklist itself referred to the learning intentions and recorded whether these were competently achieved by Magnus. Additionally, the co-created text was moderated against the Australian Curriculum: English Foundation year satisfactory work sample portfolio (ACARA, 2014).

Allowing Magnus the freedom to choose both the topic of the multimodal text and the text style (factual report) really engaged him with the process. I believe he felt very invested in the project given that it was centred on his own interests.

Outlining the entire process and explaining the learning intentions of creating the multimodal text before we began gave Magnus a better understanding of why we were completing each stage of the process. Although he was eager to begin creating the text, he seemed to understand why we were engaging in activities such as reading stimulus texts and collating facts for our report.

Prior to beginning the co-construction, I had a very rigid plan of what the text was going to be, a pre-determined topic and a stringent process through which it would be created. However, once we began investigating this topic, it became very apparent that it was of little interest to Magnus. As a result, I simply asked Magnus “What would you like to make our text about?” To which he immediately responded with “humpback whales.” From here, I was able to transfer the learning intentions to the new topic and we began again. From this point on, he showed greater interest and enthusiasm. In future, I would determine the type of text (informative, persuasive, narrative, etc.) but I would allow the child to determine the topic from the outset.

I thoroughly enjoyed the process of co-creating the text. It was enjoyable to watch Magnus’s enthusiasm and his eagerness to learn. Having an artefact on completion, which he could share with family and friends, was an additional bonus. He was proud to show others what he had created and eager to discuss the process we followed to produce the video.

I found the activity very educational. I learnt a lot about the effectiveness of incorporating semiotic systems and applying multiliteracy theory to engage students and build on their existing knowledge. It was enjoyable to put these theories into practice and see how they enhanced the co-creation process.

Key Takeaways

- Allowing children freedom of choice in determining the topic of the multimodal text engages them by appealing to their interests.

- Utilising semiotic systems and multiliteracy theory can contextualise the learning by building upon prior knowledge.

The co-constructed multimodal text

References

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2018). English (Version 8.4): Foundation Year. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/english/?year=11574&strand=Language&strand=Literacy&capability=ignore&capability=Literacy&capability=Numeracy&capability=Information+and+Communication+Technology+%28ICT%29+Capability&capability=Critical+and+Creative+Thinking&capability=Personal+and+Social+Capability&capability=Ethical+Understanding&capability=Intercultural+Understanding&priority=ignore&priority=Aboriginal+and+Torres+Strait+Islander+Histories+and+Cultures&priority=Asia+and+Australia%E2%80%99s+Engagement+with+Asia&priority=Sustainability&elaborations=true&elaborations=false&scotterms=false&isFirstPageLoad=false

Baguley, M., Pullen, D. L., & Short, M. (2010). Multiliteracies and the new world order. In D. Pullen & D. Cole (Eds.), Multiliteracies and technology enhanced education: Social practice and the global classroom (pp. 1-17). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-673-0.ch001

Bull, G., & Anstey, M. (2018). Elaborating multiliteracies through multimodal texts: Changing classroom practices and developing teacher pedagogies. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315149288

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. (2009). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/belonging_being_and_becoming_the_early_years_learning_framework_for_australia.pdf

Donaldson, J. & Scheffler, A. (2003). The snail and the whale. Koala Books

Fellowes, J., & Oakley, G. (2019). Language, literacy and early childhood education (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Department of Education and Training Victoria. (2019). Literacy teaching toolkit: Language experience approach. Victoria State Government. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/writing/Pages/teachingpracexpapproach.aspx

Iyer, R., & Luke, C. (2010). Multimodal, multiliteracies: Texts and literacies for the 21st century. In D. Pullen & D. Cole (Eds.), Multiliteracies and technology enhanced education: Social practice and the global classroom (pp. 18-34). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-673-0.ch002

Nessel, D. D., & Dixon, C. N. (Eds.). (2008). Using the language experience approach with English language learners: Strategies for engaging students and developing literacy. SAGE Publications.

Pappamihiel, N.E., Knight, J.H. (2016). Using digital storytelling as a language experience approach activity: Integrating English language learners into a museum field trip. Childhood Education, 92(4), 276-280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2016.1208005

Parker, R., Thomsen, B.S. (2019). Learning through play at school: A study of playful integrated pedagogies that foster children’s holistic skills development in the primary school classroom. The LEGO Foundation. https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1023&context=learning_processes

Parish, S. (2002). 1000 questions and answers about Australian wildlife. Steve Parish Publishing.

Peel, K., & McLennan, B. (2019). Promoting pro-social behaviour, In K. Main & D. Pendergast (Eds.), Teaching primary years: Rethinking curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (pp. 372-399). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117797

Phillips, T., Robinson, S., & Barnes, T. (2018). The five pillars of reading: Research and case study. Independence, 43(1), 40–43. https://search.informit.org/doi/pdf/10.3316/aeipt.219952

Question and Answer Encyclopedia. (1998). Dempsey Parr.

Sheldon, D. (1993). The whales’ song. Red Fox Picture Books

Slater, P. (1997). First field guide to Australian mammals. Steve Parish Publishing.