Inclusive Language

Words matter. They reflect the values and knowledge of people using them and can reinforce both negative and positive perceptions about others. Language is not neutral. Inclusive language acknowledges the unique values, skills, viewpoints, experiences, culture, abilities and experiences of individuals or groups (QUT, 2010).

Your use of inclusive language – how you speak, write and visually represent others - is an important part of open education.

Aims

- Use gender-inclusive language.

- Use a diverse representation of pronouns, including gender-neutral pronouns such as them and they.

- Ensure that all references to people, groups, populations, categories, conditions and disabilities use the appropriate verbiage and do not contain any derogatory, colloquial, inappropriate, or otherwise incorrect language.

- For historical uses that should remain in place, consider adding context, such as “a widely used term at the time.” Ensure that quotations or paraphrases using outdated terms are attributed, contextualised, and limited. Consider why this term is necessary and whether a more inclusive term could be used instead.

Actions and Considerations

- Do not assume the gender of a person so as not to misgender them.

- If needed, explicitly state what pronouns an individual uses.

- Identify any outmoded or incorrect terminology and suggest the correct replacement or re-framing.

- For historical references, if needed insert context, attribution, and/or quotations.

- Since terminology changes regularly, and acceptability is not universal, do your best to identify and use the best terminology at the time. Make time to evaluate terminology and language.

- Pay attention to connotations and make sure that stereotypes are not perpetuated. If in doubt, ask for another opinion, preferably someone with lived experience or who is from an appropriate group/background.

- Use plain language. Avoid the use of jargon, metaphors or colloquialism.

Using Gender-Inclusive Language

It has been commonly accepted for many years that the use of ‘man’ as a generic term excludes women and non-binary individuals. Words like ‘mankind’ and ‘chairman’ make people think ‘male’ rather than ‘female’ and render other genders invisible (QUT, 201). The use of ‘man’ or ‘men’ and ‘woman’ or ‘women’ is an expression of binary language and doesn’t allow for people who don’t identify as male or female. Look for words that are non-binary and gender-neutral (QUT, 2010).

| Language and practices to avoid | Good practice inclusive language |

|---|---|

| man, mankind, spokesman, chairman, workmanship, man the desk/phones, manpower |

humans, humankind, spokesperson, chairperson, quality of work/skill, attend the desk/phone, workforce |

| The supervisor must give his approval | Supervisors must give their approval |

| girls in the office, woman doctor, male nurse, cleaning lady, female professor, authoress, manageress |

office staff, doctor, nurse cleaner, professor, author, manager |

| Good morning ladies and gentlemen | Good morning colleagues/everyone |

| The guys in the office will help | The staff in the office will help |

Table 1: Gender-neutral language

Look for non-binary pronouns so that misgendering doesn’t occur.

| Subject | Object | Possessive | Reflective |

|---|---|---|---|

| She | Her | Hers | Herself |

| He | Him | His | Himself |

| They | Them | Theirs | Themselves |

| Ze | Hir | Hir/Hirs | Hirself |

| Xe | Xem | Xyr/Xyrs | Xemself |

Table 2: Non-binary pronouns

Using ‘partner’ or ‘spouse’ rather than ‘husband/wife’ or ‘girlfriend/ boyfriend’ to describe relationships will include those in de facto or same-sex relationships.

Activity: Pronouns

Have a go at this interactive pronoun resource.

Find neutral, generic terms for occupations and job titles that recognise occupational diversity. It is appropriate to refer to a person’s gender when it is a significant factor, e.g. ‘first woman Prime Minister’ or ‘first man to become nursing educator’. Where gender is irrelevant do not refer to it.

Additionally, stereotypes ignore the complexity of people’s lives. Women are often described as ‘wife of’ or ‘mother of’, irrespective of their other roles, qualifications, expertise or achievements. And again, reference to men or women, or mothers and fathers ignores people who don’t identify as male or female.

Titles of Address

Titles of address are now considered redundant when not linked to professional positions such as Professor, Doctor, Sister or Senator. Titles such as ‘Mr’ and ‘Ms’ are no longer necessarily linked to a marital status like ‘Mrs’ and ‘Miss’ and in professional arenas marital status is irrelevant. ‘Ms’ is widely used for women regardless of marital status but, rather than misgendering a person, it is better to be consistent and not use gendered titles. 'Mx' is a gender-neutral non-profession/qualification-related title that is also used. Where possible confirm with the individual their preferred title of address.

Gender and Sexuality Diversity Terms

It can help to know the meanings of words people use about gender and sexual diversity. This includes sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sex characteristics.

Respectful Language for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

Popular and acceptable usage of names changes over time. If possible, take the time to find out what the people themselves prefer to be named. This may depend upon the family structure and land area associated with each particular person (QUT, 2010). Some key information is outlined below.

- The terms ‘First Nations people’ or ‘First Peoples’ are collective terms for the original people of the land now known as Australia and their descendants. You can use them to emphasise that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples lived on this continent before European invasion and colonisation.

- It is preferable to use the term ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ – rather than ‘Indigenous’ – as an adjective, as the former term more accurately reflects cultural heritage.

- Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples prefer the terms ‘Aboriginal’ or ‘Torres Strait Islander’ person or peoples. Use these terms and avoid the term ‘Indigenous Australian’, which is not as specific. Capitalise the first letter of the terms ‘Aboriginal’, ‘Torres Strait Islander’, ‘Indigenous’ and ‘Elder’. The word ‘Indigenous’ is acceptable, however, where it forms part of an acronym within a University element, for example, Indigenous Research Unit (IRU) or Indigenous Education Statement (IES).

- The term/s ‘Aborigine/s’ can have negative connotations. Remember the term ‘Aboriginal’ does not include Torres Strait Islander people, and reference should be made to both. Never use acronyms such as ‘ATSI’ to abbreviate ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ as it is offensive to reduce the diverse members of ancient cultures and to lump them together under one cultural identity.

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) map of Indigenous Australia provides a detailed representation of language, tribal or nation groups. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples contextualise themselves by ancestral tribal and clan groups, and it is important to acknowledge each individual’s preference.

Basic respectful language means using:

- specific terms, like the name of a community, before using broader terms.

- plurals when speaking about collectives (peoples, nations, cultures, languages).

- present tense, unless speaking about a past event.

- empowering, strengths-based language (Australian Government, 2020).

Language that can be discriminatory or offensive includes:

- shorthand terms like ‘Aborigines', and ‘Islanders’ or acronyms like ‘ATSI’.

- using terms like ‘myth’, ‘legend’ or ‘folklore’ when referring to the beliefs of First Nations peoples.

- blood quantum (for example, ‘half-caste’ or percentage measures).

- ‘Us versus them’ or deficit language.

- possessive terms such as ‘our’, as in ‘our Aboriginal peoples’.

- ‘Australian Indigenous peoples’, as it also implies ownership, much like ‘our’.

- Never use acronyms such as ‘ATSI’ to abbreviate ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ as it is offensive to reduce the diverse members of ancient cultures and to lump them together under one cultural identity.

Many texts have referred to First Nations peoples in the past tense, for example: ‘The Aboriginal language existed for hundreds of years,' or ‘Torres Strait Islanders once congregated at this place.’ This use of past tense continues the historical erasure of First Nations peoples. The two statements also show a lack of understanding about diversity within either group.

Many universities have guides for how to respectfully engage with and refer to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in your community. Please engage with these guides and talk to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in your community.

Culturally-Inclusive Language

Australia has many hundreds of different language groups including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language groups. The use of culturally-inclusive language means all ethnic and cultural groups are represented as equally valid. To avoid discriminatory language, it is important not to emphasise irrelevant racial or ethnic features e.g. ‘two Asian students were accused of fraud,' (QUT, 2010).

In general, avoid referring to the ethnic and racial background of a person or group unless there is a transparently valid or legal reason for doing so. For example, ‘this week will discuss civil rights activist Dr Martin Luther King Jr. who is remembered as one of the most influential and inspirational African-American leaders in history.'

There are some standard terms used in higher education and more broadly that are more inclusive than others. The term ‘culturally and linguistically diverse’ (CALD) is a useful inclusive description for communities with diverse languages, ethnic backgrounds, nationality, dress, traditions, food, societal structures, art and religion. CALD is the preferred term for many government and community agencies as a contemporary description of ethnic communities (Ethnic Communities’ Council of Victoria, 2017).

Because there is such diversity of migration experiences – over many generations but also very recently – a range of additional definitions evolve. More formal definitions, such as ‘refugee’, asylum-seeker’, and ‘permanent humanitarian visa holder’, tend to arise from immigration visa categories. Again, context and purpose are important. A term may be necessary to determine eligibility criteria, the scope of a program or research activity, or to specify a target audience. It is important to consider whether the terms exclude or label negatively and to qualify the experiences of a group.

Here are some points to remember:

- Avoid inappropriate generalisations about ethnicity and religion. The term ‘Asians’ is sometimes used inappropriately to refer to people from diverse countries with different cultures such as China, Japan, Vietnam, India, Taiwan and Malaysia. Grouping all these cultures under one title is ambiguous and fails to recognise vast ethnic, cultural and religious differences.

- Not everyone in an ethnic group necessarily has the same religion. For example, not all Lebanese or Turkish people are Muslims and not all Muslims are Arabic or Turkish. Similarly, religions such as Judaism, Christianity and the Islamic faith are practised throughout the world, not just in particular countries.

- Talking about different cultural practices out of context can result in ridicule and stereotyping. For example, polygamous marriages, while illegal in Australia, are acceptable in some cultures and countries. Engaging in dialogues about the context in which such practices occur will offer different perspectives and a broader understanding of the world.

Note

‘Australians’ include people born in Australia or with Australian citizenship, regardless of their cultural heritage. If you need to specify a person’s ethnicity ask them how they choose to be identified.

Inclusive Language for People with a Disability

People with a disability are individuals who don’t want to be pitied, feared or ignored, or to be seen as somehow more heroic, courageous, patient, or ‘special’ than others (QUT, 2010). Avoid using the term ‘normal’ when comparing people with disabilities to people without disabilities. Remember, people with a disability are ‘disabled’ to the degree that the physical or social environment does not accommodate their disability or health condition (QUT, 2010).

If possible, find out how the individual refers to their disability – assuming reference to their disability is relevant. For example, some people may refer to themselves as ‘blind’ while others prefer vision impaired. This may also be the case for people who are Deaf or hard of hearing. Those who use Auslan sign language typically prefer to be known as ‘Deaf’, or as ‘the Deaf’ when referring to the community. Other preferred terms are people ‘with’ or ‘who has’ a particular disability or health condition.

Avoid terms that define the disability as a limitation, such as ‘confined to a wheelchair’. A wheelchair liberates; it doesn’t confine. Words like ‘victim’ or ‘sufferer’ can be dehumanising and emphasise powerlessness for people who have or have had a disability or health condition. Additionally, terms like ‘deformed’, ‘handicapped’, ‘able-bodied’, ‘physically challenged’, ‘crippled’, ‘differently-abled’ and ‘sufferer’ are not acceptable (QUT, 2010).

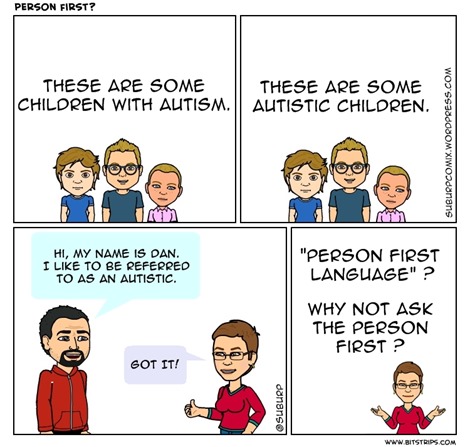

Identity-first language is strongly, but not universally, preferred among Autistic people and many disabled people. However, there are sharp differences of opinion between Autistic people/disabled people and parents/carers of Autistic or disabled people).

Use Plain Language

When we use lingo or acronyms that are not commonly understood by others we are automatically excluding them. Additionally, metaphors may be confusing for English as Second Language learners as well as people with autism. In order to be more inclusive avoid the use of lingo and metaphors. Keeping it simple is the key to good writing.

Resource

The Hemingway Editor is an excellent resource to test the readability of your work. The app highlights lengthy, complex sentences and common errors for you to address.

Good practice example: Gender and sexuality inclusion in 'LGBTIQ+ healthcare'

Sexual and gender identities can present unique needs and difficulties for those accessing healthcare. The LGBTQ+ community is incredibly diverse, and the difficulties that this community faces in accessing healthcare are complicated further by the intersectionality of various races, ages, abilities, and more. LGBTQ+ Healthcare was designed with this in mind. It was “created by and in collaboration with members of the LGBTQ+ community."

Sexual and gender identities can present unique needs and difficulties for those accessing healthcare. The LGBTQ+ community is incredibly diverse, and the difficulties that this community faces in accessing healthcare are complicated further by the intersectionality of various races, ages, abilities, and more. LGBTQ+ Healthcare was designed with this in mind. It was “created by and in collaboration with members of the LGBTQ+ community."

The book demonstrates ways in which gender and sexual identity can influence healthcare by putting the learner in the place of the patient. Through interactive activities, the learner can better understand how something as commonplace as an intake form can be dehumanising or alienating for some patients and what a dramatic difference some small changes can make. These activities present common healthcare scenarios that many in the LGBTQ+ community face and challenge the learner to identify the areas for improvement before guiding them through a more inclusive and compassionate version of the same scenario.

Questions to ask yourself if you're creating a biology or healthcare OER:

- How can we affirm our transgender and intersex students when we talk about X and Y chromosomes?

- How will students with same-sex parents interpret and internalise OER about meiosis and sexual reproduction?

- How do all gender identities and sexual orientations fit into our understanding of science, development, and evolution?

- Can we create safe spaces for scientific exploration and protect trans youth in education?

Inclusive Language Resources

To help authors write in ways that are inclusive and respectful of diversity, most style guides now include guidelines for inclusive and bias-free language. For example:

- Australian Government Style Manual contains an inclusive language section that provides advice on writing respectfully about:

- The New Zealand Government's Content Design Guidelines contain inclusive language guides for:

- Te reo Māori – using Māori language tags (for more detailed advice on the Māori language see Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori (Māori Language Commission)'s Guidelines for Māori Language Orthography).

- disability language

- gender-inclusive language

- age-inclusive language and content.

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association contains general principles for reducing bias, as well as bias-free language guidelines for writing about:

- Other resources

Copyright note: This section has been adapted in part from:

- 'Inclusive and Bias-Free Language Guidelines' in The CAUL OER Collective Publishing Workflow by Council of Australian University Librarians, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- LGBTIQ Healthcare book cover is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

Acknowledgments: I would like to acknowledge Flic French (Student Engagement Manager), University of Queensland, Clare O'Hanlon (Senior Learning Librarian), La Trobe University and Ash Barber (Support Librarian), University of South Australia for their substantial contributions to this chapter.