Diverse Examples and Balanced Perspectives

Represent issues relevant to diverse populations. Don’t avoid or underestimate the impacts on diverse populations. Include diverse examples and balanced perspectives in your OER.

Aims

- Represent issues relevant to diverse populations and ensure that you are not avoiding or underestimating the impacts on diverse populations. Examples include social problems, health issues, political issues, business practices, economic conditions, and so on.

- Ensure that diverse contexts are included and that all examples are comprehensible to everyone, while being sure to avoid stereotypes.

- Most discipline experts will defer to the academic viewpoint of any key concept, but they should consider alternative points of view.

- Consider intersectionality while being aware of ethnocentrism and how this may impact your own biases.

Actions and Considerations

- Review, and consider having students review, problems and exercises, considering their context and inclusivity.

- Review terminology, contexts, and situations presented in problems/applications to ensure that they are comprehensible to all populations.

- Write and use examples that include diverse people, organisations, geographies, and situations.

- Avoid negative stereotypes or sensitive subjects in problems and applications unless the subject matter demands it.

- For each topic/concept, consider the perspective of all populations in relation to controversies, arguments, alternative points, and so on.

- Suggest additions to expose a varied point of view and widen the context for students.

- Avoid characterisations that lead to generalisation – e.g. “rural communities tend to support gun rights.” If a generalisation like that must be stated, provide more context, such as why, and include any counterpoints from “within” that generalisation.

- Make no assumptions about prior knowledge, especially from different subjects/cultural contexts. Even common cultural elements such as Disney characters, pop music or popular games or shows are not universal.

- Engage a sensitivity reader to review your text if you are writing about cultures or situations outside your lived experience.

Good practice example – ‘Fighting Phytochemicals’

An example that is inclusive, informative, and requires no previous knowledge can be found in the open Human Biology textbook section on “Fighting Phytochemicals.”

Diversify Case Studies

Are your case studies taken from a range of international examples and do they use diverse names and avoid stereotypes? If your case studies include video, do they use authentic accents? Ensure your case studies don’t perpetuate limiting positive stereotypes; for example, black people being portrayed as good at sport or Asian people portrayed as good at science.

Be Aware of Ethnocentrism

It’s easy for ethnocentrism – voluntarily or involuntarily viewing the world through the lens of your own ethnicity or culture without taking other ethnicities or cultures into account – to creep into the content and presentation of a textbook, so this is something you’ll need to be aware of. This doesn’t mean you should try to write a textbook that fits every culture and perspective – just be respectful.

One of the benefits of open textbooks is that instructors from different countries and cultures can customise them to suit their needs.

For example, you may decide to adapt an American open textbook to fit the Australian context or expand the content to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives.

Sensitivity Reading

Consider engaging a sensitivity reader to review your text if you are writing about cultures or situations outside your lived experience.

Be Aware of Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that was developed to address how people’s experiences are shaped based on their intersecting social identities (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, class, age, etc.). This approach focuses on the importance of considering power, privilege, and social structures in relation to people’s access to resources, experiences of discrimination, and interpersonal interactions (Sabik, 2021). The below video explains intersectionality in more detail.

Video: What is Intersectionality? [2 mins, 49 secs]

Note: Close captions are available by clicking on the CC button in the video.

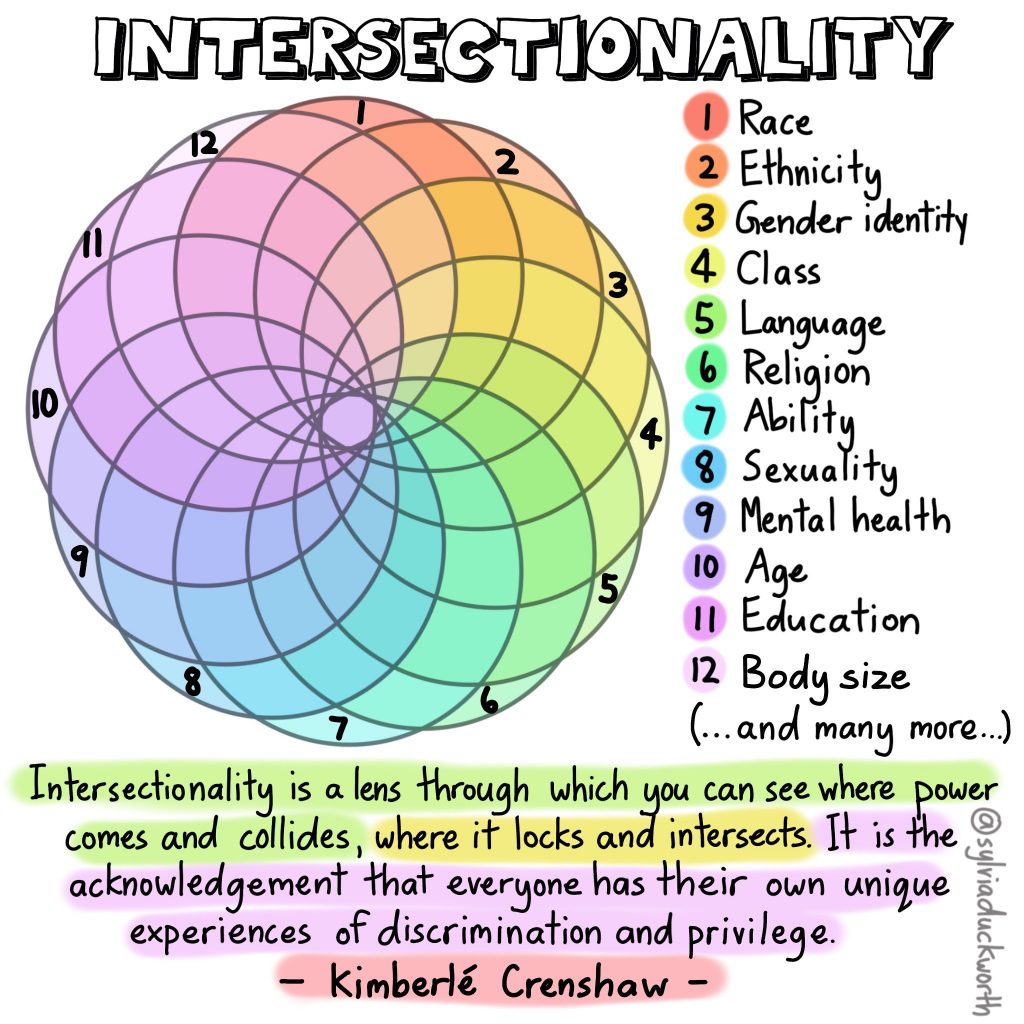

The following graphic entitled “Intersectionality” visually displays how social identities intersect with one another and are wrapped in systems of power. For example, using the imagery of a spirograph, Duckworth (2020) colour-codes various social identities including race, ethnicity, gender identity, class, language, religion, ability, sexuality, mental health, age, education, and body size.

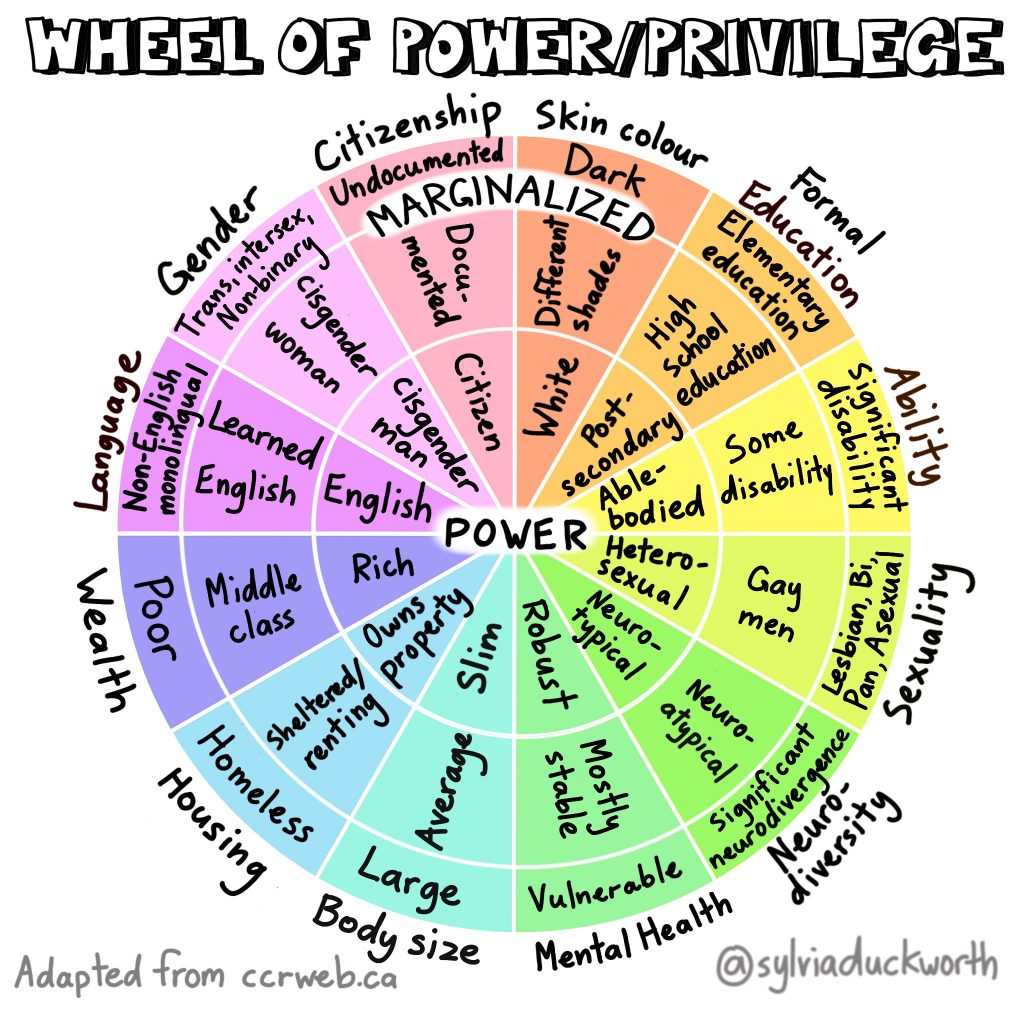

Sylvia Duckworth’s “wheel of power/privilege” is another visual representation of how power, privilege, and social identities intersect. The graphic below uses the imagery of a wheel, sectioned off by the following social identities and respective categories:

- Citizenship: citizen, documented, undocumented

- Skin colour: white, different shades, dark

- Formal education: post-secondary, high school, elementary

- Ability: able-bodied, some disability, significant disability

- Sexuality: heterosexual; gay men; lesbian, bi, pan, asexual

- Neurodiversity: neurotypical, neuroatypical, significant neurodivergence

- Mental health: robust, mostly stable, vulnerable

- Body size: slim, average, large

- Housing: owns the property, sheltered/renting, homeless

- Wealth: rich, middle class, poor

- Language: English, Learned English, non-English monolingual

- Gender: cisgender man; cisgender woman; trans, intersex, nonbinary

Activity: Define Yourself

Referring back to the identities in the Wheel of Power/Privilege think about how you define yourself, and where your salient social identities are located on the wheel. Get curious about:

- How close or far away from the centre are you?

- How does your level of power shift as you place yourself in different identity categories?

- Thinking about your institution, where do students, staff, administrators, and/or faculty reside?

- Do you think any categories are missing?

You are invited to record your reflection in the way that works best for you, which may include writing, drawing, creating an audio or video file, mind map or any other method that will allow you to document your ideas and refine them at the end of this module.

Alternatively, a text-based note-taking space is provided below. Any notes you take here remain entirely confidential and visible only to you. Use this space as you wish to keep track of your thoughts, learning, and activity responses. Download a text copy of your notes before moving on to the next page to ensure you don’t lose any of your work!

Good Practice Example – Teaching in the University: Learning from Graduate Students and Early Career Faculty

Teaching in the University: Learning from Graduate Students and Early Career Faculty provides insight and strategies for successful teaching, advising, and mentoring postsecondary students. This book is designed for new university teaching faculty and graduate teaching assistants looking for innovative teaching resources. This textbook provides university instructors free access to high-quality teaching materials based on the experiences of fellow new instructors. Twenty contributors and two co-editors from the current students and alumni of university teaching scholars’ programs offer this resource for fellow faculty and graduate students to improve instruction and engagement. Each chapter comes from the experiences and expertise of these talented individuals who speak directly to their peers. Although centring on the STEM faculty, the authors are of diverse genders and backgrounds. The text also contains diverse points of view with one vignette titled ‘No, really, I don’t have Internet’ and another on indigenising the classroom. This book is an exemplar for having diverse contributors and diverse perspectives.

Teaching in the University: Learning from Graduate Students and Early Career Faculty provides insight and strategies for successful teaching, advising, and mentoring postsecondary students. This book is designed for new university teaching faculty and graduate teaching assistants looking for innovative teaching resources. This textbook provides university instructors free access to high-quality teaching materials based on the experiences of fellow new instructors. Twenty contributors and two co-editors from the current students and alumni of university teaching scholars’ programs offer this resource for fellow faculty and graduate students to improve instruction and engagement. Each chapter comes from the experiences and expertise of these talented individuals who speak directly to their peers. Although centring on the STEM faculty, the authors are of diverse genders and backgrounds. The text also contains diverse points of view with one vignette titled ‘No, really, I don’t have Internet’ and another on indigenising the classroom. This book is an exemplar for having diverse contributors and diverse perspectives.

Copyright note: This section has been adapted in part from:

- ‘Positionality and Intersectionality,’ in Universal Design for Learning (UDL) for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA) by Darla Benton Kearney, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ‘Be Aware of Ethnocentrism’ is based on ‘Accessibility, Diversity, and Inclusion’ in Self-Publishing Guide by Lauri M. Aesoph, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ‘Sensitivity Reading’ is based on Writing, editing, and publishing Indigenous stories: Sensitivity reading by the University of Alberta Library, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

- Teaching in the University book cover licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.