Humanising and democratising the IT revolution

A People’s Internet is possible … Silicon Valley loves a good disruption, so let’s give them one (Scholz, 2016).

History is made by humans not by machines (Taplin, 2017).

Public goods and moral universals

If anything has become clear during the present enquiry it is that humanising the IT revolution requires something other than technical innovation. It obviously has many technical implications but the key drivers of a multi-faceted shift toward a different modus operandi are not technical but found within human, social and cultural contexts.

The current ‘de-evolved’ Internet and explosion of radically ambivalent high-tech innovations provide clear evidence of an extended and continuing cultural failure. Despite its many positive aspects we cannot avoid the fact that the US has become enmeshed in its own downward spiral. Countless words have been written on this topic but one core concern is its singular lack of success in creating viable ‘public goods’ such as free health care, quality education, protection from random violence and public wellbeing on a broad scale. Umair Haque (2017) argues that the lack of such goods separates the US from all other advanced nations. The former spring from ‘moral universals’ that he suggests are largely absent from the US but which are needed to ‘anchor a society in a genuinely shared prosperity.’ Such universals don’t simply ‘spread the wealth’ but help to civilise people. They ‘let people grow to become sane, humane, intelligent human beings’ – all characteristics upon which democracy depends. Any society lacking these characteristics simply runs out of steam. In this view, what happened in the US is that:

They have never seen – and still don’t see – the benefits: the civilising process that democracy depends on. Thus, in America today, there are no broad, genuine, or accessible civilising mechanisms left. … The natural consequence of failing to civilise is breaking down as a democracy – democracy no longer exists in the sense of “people cooperating by voting to give each other greater prosperity”. They have merely learned to take prosperity away from one another (Haque, 2017).

Such suggestions must be treated as debatable, yet Haque is not alone in advancing this general argument. Noted Australian journalist, Peter Greste is in broad agreement. In his opinion ‘since America’s founding, its leaders have recognised that the country’s real authority – as opposed to power – rests on its moral standing,’ (Greste, 2017). Yet the routine outpouring of ignorance by the former US president ‘placed the US on the same moral plane as some of the world’s most ruthless tyrants.’ He finds this ‘deeply troubling’ because ‘without a clear moral framework, the world becomes a snake pit of competing national interests’ (Greste, 2017). Such sentiments provide yet another factor that helps to account for the debased version of Internet usage and commerce that became normalised over recent years.

Values, worldviews, research

Taken together, the views discussed above go a long way toward explaining why the Internet became compromised. It not only failed to deliver on the idealism of its early proponents but also became a source of exploitation, danger and oppression. The many and varied uses of IT are divided between the genuinely helpful and those that are routinely misused. At least two underlying rationales can be briefly mentioned here. One springs from value and worldview considerations. An outlook typified by greed, selfishness, exploitation and an underlying disregard for real human and social needs will produce, and has produced, applications adapted to these uses. On the other hand positive values such as generosity, care and respect, especially when coupled with socio-centric or world-centric outlooks, will be directed toward more widely useful and constructive uses. This identifies a core difference between, say, monopoly platforms that treat people like mindless sheep by driving them into the arms of the advertising industry, and socially useful innovations such as local currencies, that respect and build local economic and social wellbeing.

As noted above, a different, but related, rationale can be drawn from evidence-based Earth science that makes it abundantly clear that humanity is under real and unrelenting pressure to re-think the conditions of its tenancy on this small planet. Here values such as caring, foresight and obligations to future generations come to the fore. They simply make better sense in this context. Roger Dennis (2017) is not alone in suggesting that leaders in technology need broader and deeper views of the world. In fact he suggests that ‘the industry doesn’t need more programmers, it urgently needs more women, ethicists and philosophers’. Political decision-making about the uses and abuses of all classes of high technology need to be returned from ‘defence’ contractors, specialised labs and private corporations to well-staffed and properly equipped locations firmly placed within the governance and related structures of civil societies. This process will certainly include private initiatives that draw both on progressive values and emerging technologies to help break the multi-monopolies of over-dominant players (Ahmed, 2017). It follows that effective and helpful innovation does not necessarily mean expanding the size of governments per se, but it will certainly require overturning any residual notion that ‘markets rule.’ Clearly they don’t and can’t.

Another way to ‘humanise the future’ is to ensure that sufficient human and economic resources are directed toward high quality evaluation and research. In late 2017, for example, the Oxford Internet Institute found clear statistical evidence that during the previous US election ‘the balance between freedom of speech and election interference has been tipped.’ Specifically ‘Twitter users got more information, polarising and conspiratorial content than professionally produced news’ and ‘average levels of misinformation were higher in swing states than in uncontested states’ (Howard & Kollanyi, 2017). Junk news is an ideal medium for the further propagation of junk science. So the researchers came up with a short list of actions to deal with the abuses they uncovered. These include:

- Up-dating the Uniform Commercial Code … forcing companies to adhere to basic anti-spam and truth-in-advertising rules;

- Ensuring that paid political content on social media is accompanied by the disclosure of backers;

- Social media platforms be required to file political advertising and bot networks with election officials; and,

- Bots in general be clearly identified to users (Howard & Kollanyi, 2017).

Not long after this, The Economist magazine (not particularly well known for having a progressive outlook) ran a ‘leader’ story that posed the question ‘Do social media threaten democracy?’ One reason provided was that ‘far from bringing enlightenment, social media have been spreading poison’ (Economist, 2017). Clearly disquiet with social media is not limited to a few marginal sources. During 2017 disruptions to vital democratic processes – especially during the US election and the ‘Brexit’ referendum – carried out by Russian and other sources were acknowledged and documented in detail (Cadwalladr, 2017). Unfortunately these concerns were amplified many times over during the disastrous 2020 US election campaign and its violent aftermath. Clearly there is still a vast amount of work yet to be done in order to ‘clean up’ and re-orient social media toward more constructive ends. Some of the latter are briefly outlined below.

Sharing cities, platform cooperativism

Nowhere is the potential for new kinds of IT-enabled organisations and practices more timely and useful than in relation to cities and cooperatives. For example, in Darren Sharp’s (2016) view the notion of Sharing Cities – rather than merely ‘smart’ ones lacking a social contract with citizens – can serve as ‘an antidote to top-down technologically deterministic visions of the future.’ His vision is one in which existing infrastructure such as wi-fi and spaces within public buildings are made more widely available. He looks to Seoul and Amsterdam for examples of how a sharing approach is actually working. In summary he suggests that ‘Sharing Cities create pathways for participation that recognise the city as a commons and give everyone the opportunity to enjoy access to common goods and create new forms of shared value, knowledge and prosperity’ (Sharp, 2016). That this is not an isolated example and should be seen in a much wider context is demonstrated in a fine collection of 137 case studies. This is much more than a ‘how-to’ reference work as it presents a vision for cities that situate people (rather than the market, technology or governance) at the core of what cities are and how they operate (Shareable, 2017).

In a similar vein Rushkoff (2016) explores the potential of democratically focused social and economic innovations. Drawing inspiration from existing examples he highlights possible characteristics of IT-enabled ‘steady state’ enterprises, ‘platform cooperatives’ and ‘genuinely distributist businesses.’ Such features include the need to ‘reclaim values’ in support of ‘women’s equality, integrative medicine, worker ownership and local currency’ (Rushkoff, 2016, p. 215-37). Platform cooperatives are among the most promising of new IT-enabled and democratically constituted organisational forms. One of the most thorough treatments of this emergent phenomenon is provided by Trebor Scholz. As with many other observers he is clear about the need for change. For example he writes that:

We cannot have a conversation about labour platforms without first acknowledging that they depend on exploited human lives all along their global supply chains, starting with the hardware without which this entire “weightless” economy would sink to the bottom of the ocean. … (Similarly) this isn’t merely a continuation of pre-digital capitalism as we know it, there are notable discontinuities – new levels of exploitation and concentration of wealth for which I penned the term crowd fleecing. Crowd fleecing is a new form of exploitation, put in place by four or five upstarts, to draw on a global pool of millions of workers in real time (Scholz, 2016, p.3-4).

In Scholz’ (2016, p18-21) view what he calls ‘platform cooperativism’ is the coming together of three elements: the existing technical know-how of existing monopoly platforms, a sense of solidarity and reframing concepts like ‘innovation’ with a view to sharing the rewards. He also provides a typology of platform cooperatives and a useful list of guiding principles:

- Ownership.

- Decent pay and income security.

- Transparency and data portability.

- Appreciation and acknowledgement.

- Co-determined work.

- A protective legal framework.

- Portable worker protections and benefits.

- Protection against arbitrary behaviour.

- Rejection of excessive workplace surveillance.

- The right to log off.

For Scholz (2016) the core of the issue is ‘a new story about sharing, aggregation, openness and cooperation.’ Equally significant is that his view of the present incumbents may be iconoclastic but it is certainly not punitive. Rather:

The importance of platform cooperativism does not lie in “killing the death star platforms.” It does not come from destroying the dark overlords like Uber but it comes from writing over them in people’s minds, and then inserting them back into the mainstream (Scholz, 2016, p.26).

This is clearly a human and social process that seeks to recover values that were cast aside in the single-minded pursuit of growth and profit. This, it seems, is the very foundational work that can help to rehumanise and democratise both the Internet and the IT revolution on which it is founded.

Values and moral development

This and the previous chapters have commented on certain values and worldview limitations that arguably characterise both the ethos of Silicon Valley and some of its leading figures. In 2017 John Naughton took up the issue of what he calls the ‘astonishing naivety of the tech crowd’. For him a plausible explanation can be found in the restricted nature of the latter’s educational backgrounds – mainly mathematics, engineering and computer science. He noted that these are ‘wonderful disciplines’ but then went on to suggest that:

Mastering them teaches students very little about society or history – or indeed about human nature. As a consequence, the new masters of our universe are people who are essentially only half-educated. They have had no exposure to the humanities or the social sciences, the academic disciplines that aim to provide some understanding of how society works, of history and of the roles that beliefs, philosophies, laws, norms, religion and customs play in the evolution of human culture (Naughton, 2017b).

Some may regard these as contentious topics yet there are quite straightforward ways of addressing them in this context. One is to go back to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) that was signed off by the United Nations (UN) in 1948. Here there are a couple of specific articles that speak directly to the themes of this paper, as follows:

Article 12

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Article 22

Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realisation, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organisation and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality (United Nations, 1948).

These statements clearly established that the nations of the world were firm in their belief that the privacy and dignity of all human beings were to be respected and maintained in perpetuity. After the horror of two disastrous world wars they were deemed to be of particular value and significance. Yet the high-tech sector almost everywhere seems to have lost sight of these vital commitments. Wendell Bell later took up the theme of ‘universal human values’ in volume two of his masterwork The Foundations of Futures Studies. Bell reminds us that what might be called the ‘near-universals’ of human life have never been restricted to a particular time or place. Values that promote survival imperatives are widely adopted because they support human well-being and civilisational progress.

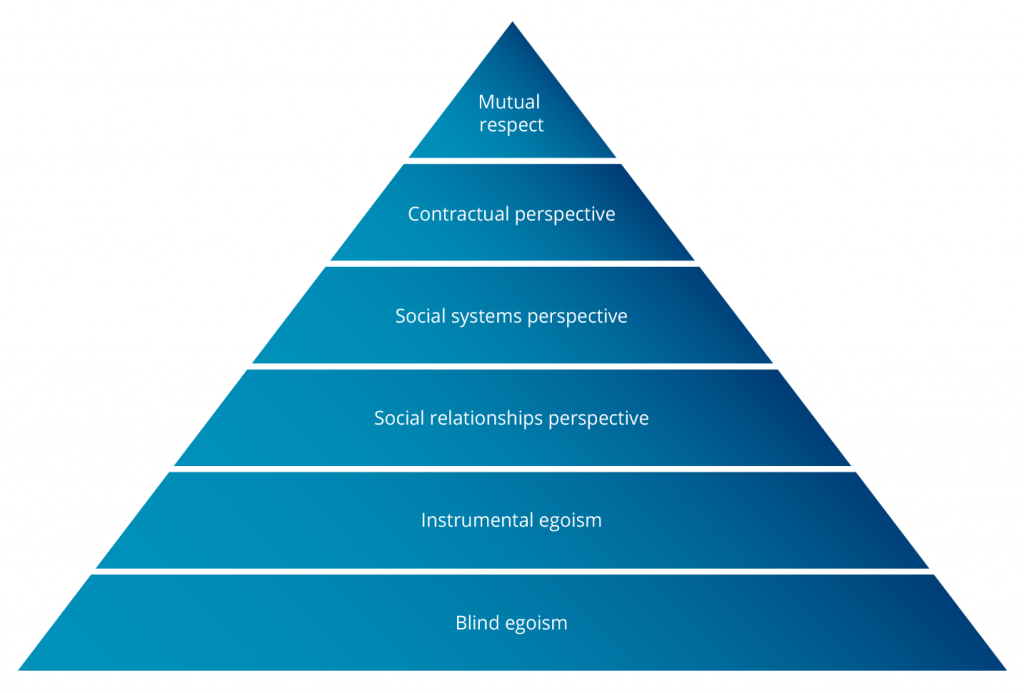

He continues by discussing four values that he considers of major importance: ‘knowledge, evaluation, justice and cooperation,’ (Bell, 1997). He also mentions those from a survey carried out by Kidder: ‘love, truthfulness, fairness, freedom, unity, tolerance, responsibility and respect for life’ (Bell, 1997, p.181). Taken out of context such lists mean very little but they do indicate general orientations that have been highly regarded by most cultures over long periods of time. As such they are not to be readily dismissed. The picture becomes clearer still when Bell reviews Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, summarised in Figure 2. (Kohlberg, et al, 1983).

Bell (1997, p.218) summarises some of the features of these stages in the following way.

Stage 6: Universal principles of justice, the equality of human rights and respect for individual human dignity are deemed to transcend the law itself. In this view it is rational to believe that ‘doing the right thing’ is based on an understanding that universal moral principles are valid. Personal decisions to uphold such principles affirm their continued salience over time.

Stage 5: A contractual perspective requires impartial support for agreed core values, including that of trust in fulfilling contractual obligations. To this end it is helpful to recognise fundamental rights, such as the right to life and liberty, while not necessarily being constrained by fashion or transient opinion. Defensible ethical behaviour involves freely accepting such obligations and actively seeking the greatest benefit for the common good.

Stage 4: Embodies a focus on large and more dominant social institutions and the wider society as a whole. Group welfare is a primary concern, and it is in this context that obligations need to be fulfilled.

Stage 3: The need to be, and be seen as, a good person. Sustained loyalty is related primarily to particular groups and organisations. Individuals are keenly alert to the expectations of others in most situations. They are self-critical within these limited domains.

Stage 2: A bi-directional stance in which individuals pursue their own agendas while also remaining open to, and accepting of, those of others. Behaviour is, however, socially sanctioned since it is dependent upon on approval and reinforcement from others.

Stage 1: The locus of decision-making is largely external and, as such, lies beyond the individual. Motivation is therefore focused on routine, convergent behaviour and the avoidance of sanctions. ‘Doing right thing’ is identified with successfully following pre-existing rules and procedures.

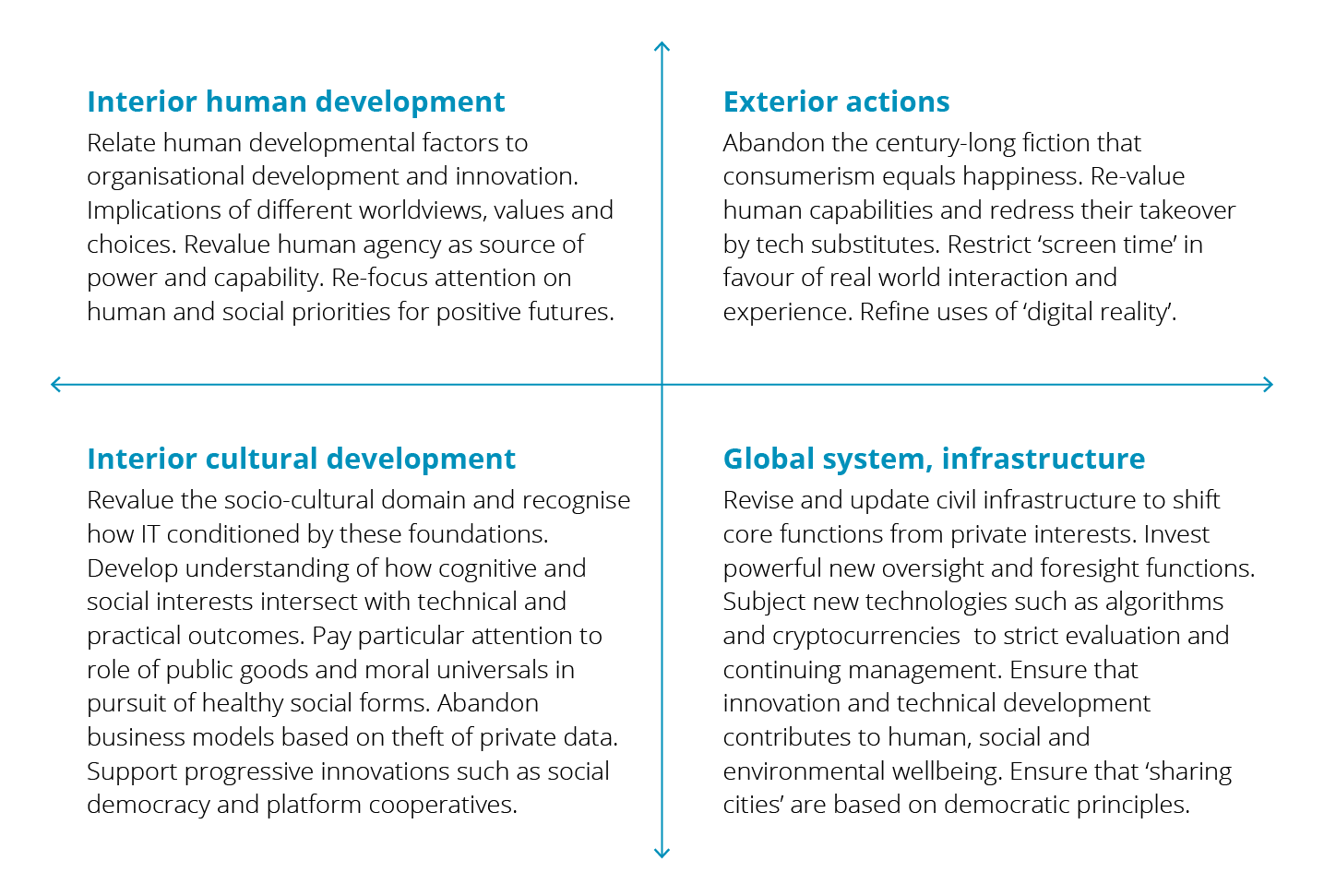

It is for the reader to consider how well or badly the values and human qualities suggested here may apply to specific individuals and organisations that have colonised the Internet for their own limited purposes. But at the very least Bell and Kohlberg provide us with clear and reliable criteria that can legitimately be used as an evaluative scale. So in terms of moral development thus defined, some organisations and their executive leaders may find themselves hard pressed to provide adequate answers. Which has huge social implications. When the question of re-negotiating social contracts is raised – and it will be repeatedly – then interlocutors can legitimately seek evidence for the fulfilment of these criteria at the highest levels. Possibly the most useful guidance and overall summary is provided by Bell himself when he suggests that ‘ People live best who live for others as well as for themselves’ (Bell, 1997, p.275). Finally Figure 3 summarises some of the key suggestions made throughout this series back to an Integral perspective.

A straightforward four-quadrant analysis illustrates how various right hand quadrant phenomena (including technology, infrastructure and exterior actions) can usefully be related back to various left hand quadrant equivalents (values, worldviews, stages of development etc. as expressed through a variety of cultural norms and conditions). It follows that one way of promoting more humanised and democratic uses of any technology is to simply open to these left-hand quadrant realities and take them fully into account.

The story thus far has shown how the early Internet was shaped and conditioned by specific human and cultural forces within the U.S. After a fairly benign, government-funded start, a handful of entrepreneurs took over and, with little or no thought for wider consequences, actively fashioned the conditions for their own success. Tax laws were revised. Anti-trust regulations that had earlier been applied to Microsoft and the Bell Telephone Company were set aside. Strategies were undertaken through which private monopoly platforms would grow unhindered into the world-spanning behemoths of today. The rise of neoliberalism turbo-charged this process. Following Hayek, it viewed the government as an impediment to ‘progress’ and the market as an unquestioned good. These tendencies, along with Rand’s nihilistic view of human existence, all helped to bring the present constellation of rootless and invasive entities to its present condition.

In an alternative world, competent far-sighted governance would have set the conditions for such enterprises and modified them progressively over time. Human rights (including the right to dignity, privacy and freedom from oppression) would have been respected and consciously built into the foundations of the Internet. Corporations would have learned to respect users and therefore to ask before expropriating creative work and private data wholesale for commercial gain. Tax laws that mediated fairly between corporate and social needs would have helped to ensure a steady flow of income for social expenditures. When entities grew too large they would have been broken up or otherwise compelled to adapt. Currently, however, we do not live in that world.

Yet, as can be seen from some of the many examples outlined above, there are a host of reasons to support informed optimism and hope, the framing of real solutions. Furthermore, it is helpful to remember that some aspects of our situation are not entirely new. When Martin Luther hammered a copy of his 93 theses onto the Wittenberg church door some five centuries ago, he set himself against the oligarch of the day – the all-powerful Catholic Church. He questioned the legitimacy of that vast institution and, at the same time, began a process that both destroyed its business model and made way for alternatives. Today the underlying dynamic is suggestive but there are also clear differences. Luther’s stripped down version of Christianity was a radical change but it still provided people with a sturdy moral framework to guide their thinking and behaviour. Such foundational certainties are more elusive in our own time. On the other hand this very fact arguably provides a rationale for recovering, re-valuing and applying some of the universal human values outlined above. The latter are perhaps among the most viable sources of strength and continuity available during times of transformation and change.

The legitimacy of the Internet oligarchs is now in doubt from many quarters and for a variety of reasons, so limits and conditions are likely to be progressively imposed. Similarly, the business model that daily abuses countless human beings is unlikely to survive without major changes being wrought by newly enfranchised, democratically constituted cooperatives and civil authorities. While government actions may be slow and, at times uncertain, this study suggests that a host of responses, innovations and alternatives is under active development. It is inconceivable that these will not change the nature of digital engagement over time. So it is indeed possible to look ahead with qualified optimism and to anticipate a new and different renaissance. A renaissance that sets aside technological adventurism and wild, unconstrained innovation, in favour of positive human values and cultural traditions that balance human dignity and rights on the one hand with the enhanced stewardship of natural systems on the other.