2 Theoretical Conceptualisations of Wellbeing

Susan Carter and Andersen, Cecily

- There is a lack of consensus in the literature as to exactly what wellbeing is, as well as an array of wellbeing models.

- The challenge is for educational contexts to clearly define wellbeing and select or develop a model of the concept before trying to implement wellbeing programs.

Guiding question

- What is wellbeing?

Introduction

Wellbeing is now a concept at the core of many educational policy agendas and practices. Increasing attention is focussed on both student and staff mental and emotional wellbeing initiatives and polices, in order to equip individuals with the social and emotional skills, knowledge and the disposition required to operate and contribute productively within both an educational setting and the broader societal context.

This Chapter will explore the following questions: What does the concept of wellbeing mean? Does the term wellbeing have the same meaning for all individuals and groups within a school? Does the concept of wellbeing hold constant across time and events despite the diversity of experiences, culture, beliefs and values evident within educational contexts? What foundational approaches and models inform wellbeing educational initiatives? And what is the role of education in the wellbeing of student and staff? In exploring the above questions, the theoretical concept of wellbeing will be explored by examining definitions of wellbeing, wellness and mental health; investigating theoretical conceptualisations of wellbeing; and by exploring subjective wellbeing as an approach to fostering wellbeing an examining the place of wellbeing in educational contexts.

What is wellbeing?

The seeking of a definition for wellbeing is a complex pursuit, as increasingly it is utilised in conversations, on the community and global media, and within the literature, in many different ways, with wellbeing seemingly taking shape as a chameleon (Carter, 2016). Originally there appeared two specific schools of thought where wellbeing was seen either as hedonic or eudemonic.

From a hedonic view, focusing on happiness can be seen as the totality of pleasurable moments. Philosophers such as Hobbes viewed wellbeing as “a pursuit of human appetites”, DeSade held that it was the “pursuit of sensations and pleasure” and Bentham claimed that “through maximising pleasure and self-interest that the good society is built” (cited in Husain, 2008). Other philosophers held a somewhat different view, deeming that people experience happiness in the expression of their virtues, engaged in what they believe is worth doing (Carter, 2016). This notion of eudemonia – being true to one’s inner self can be equated with an eudemonic perspective of wellbeing. Building upon the eudemonic view of wellbeing is Maslow’s (1970) concept of self- actualization and Deci and Ryan’s (2000) self-determination theory. An individual’s or community’s quality of life is a direct function of the conditions that arise in life, and how an individual or community utilises the conditions that life presents. How an individual or community perceives the condition, thinks and feels about those conditions, what is done and, ultimately, what consequences follow from all these inputs in turn becomes a function of how the conditions are perceived. People’s perceptions, their feelings, their thoughts, and their actions, then, have a direct impact on their own and others’ living conditions (Michalos, 2007).

McCallum and Price (2016) argue that wellbeing has emerged as “something everyone seemingly aims for, and arguably has a right to” (McCallum & Price, 2016, p.2). While wellbeing is not a new concept, it has become an important concept within contemporary school community contexts. However, identifying an agreed definition of wellbeing, in addition to establishing a consensus on how quality wellbeing can be achieved and sustained, is far more problematic with the term wellbeing often poorly defined and under-theorised (Camfield, Streuli & Woodhead, 2009). To compound the issue of definition inconsistency, wellbeing is often used interchangeably with other terms such as ‘happiness’, ‘flourishing’, ‘enjoying a good life’ and ‘life satisfaction’, all which have very different interpretations and underlying meanings.

Bradburn (1969) (as cited in Dodge, Daly, Huyton & Saunders, 2012) defined wellbeing as being present when an individual is high in psychological wellbeing, where an excess of positivity (positive affect) predominates over negative affect. In contrast, Shah and Marks (2004) argued that wellbeing is more than just positive affect (happiness, feeling satisfied), with feeling fulfilled and developing as a person an equally important aspect in defining wellbeing. Diener et al. (1999) extend the definition of wellbeing even further by defining wellbeing as subjective (thus the term subjective wellbeing, {SWB}) more specifically as consisting of three essential interrelated components: life satisfaction, pleasant affect, and unpleasant affect.

The characteristic intensity with which people perceive their affective states, has no bearing on overall subjective well-being (Larsen, Diener & Emmons, 1985). It seems that the predominant predictor of overall SWB is the rate of positive compared to negative states in a person’s life, throughout time (Larsen, Diener, & Emmons, 1985). “Because subjective well-being refers to affective experiences and cognitive judgments, self-report measures of subjective wellbeing are indispensable” (Larsen & Eid, 2008, p. 4).

Together with his associates Ed Diener designed the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985), which developed into the standard measure of life satisfaction in the wellbeing field. The implications concerning the measurement of SWB are that:

- SWB can be assessed by self-report with significant consistency and authority (Larsen & Eid, 2008).

- Each measurement method has drawbacks and benefits (Larsen & Eid, 2008).

- Comprehensive assessment of SWB necessitates a multimethod assessment tool (Diener, 2009; Diener & Eid, 2006).

Diener (2006) suggested that people over emphasise their emotional intensity and underestimate and underrate the frequency of their positive affect when recollecting emotional moments. This research signifies that there is no single cause of SWB. It seems apparent then, that certain conditions appear to be essential for high SWB {e.g., mental health, positive social relationships}, but are not singularly sufficient to cause happiness (Diener, 2006). Diener’s work has detected a number of circumstances that seem to be required for, or correlated with happiness, however no one condition or characteristic is adequate to ensure happiness in itself (Larsen & Eid, 2008).

It should be noted that there is evidence that diverse circumstances and outcomes make people happy. Diener and colleagues have shown that the links to happiness alter between young versus old people (Diener, 2000). So what makes a younger person happy may not make an older person happy. Likewise, Diener, Suh, Smith, and Shao (1995) reported that there are different connections to happiness in differing cultures. Diener (2000) has suggested that that there are likely universals, such as experiencing close positive social relationships that are associated with happiness by almost everyone. Larsen and Eid (2008, p 8.) cleverly suggest a cooking analogy explaining that when cooking some ingredients are essential, many just enhance flavour or texture but no singular ingredient, produces the desired outcome, rather all ingredients need to come together in the right way for success to be achieved.

SWB appears to contribute to beneficial outcomes in life. Diener (2000), along with his colleagues has determined that happy people are more creative and sociable; have increased likelihood of longevity; display generally sturdier immune systems; earn more money; are good leaders; and display generally better citizenship in their workplace. Furthermore, numerous positive outcomes were linked to happiness, such as marital satisfaction, job satisfaction, and improved coping. Therefore, high SWB is particularly desirable at individual, at educational system levels, and at societal levels. It therefore makes sense to invest in promoting a culture in educational contexts where wellbeing is important. This text will aim to explore, how educational contexts can create a culture where SWB is valued, and high levels of SWB are desired as outcomes, planned for and hopefully achieved.

McCallum and Price (2016) propose an even more encompassing definition of wellbeing outlining it as diverse and fluid, respecting the beliefs and values of individual, family, and community; and experiences, culture, opportunities, and contexts across time and change. They aver that it encompasses interwoven environmental, collective, and individual elements that interact across a lifespan (McCallum & Price, 2016). Despite a range of notions encompassed in wellbeing definitions, wellbeing can then be described in very broad terms as a holistic, balanced life experience where wellbeing needs to be considered in relation to how an individual feels and functions across several areas, including cognitive, emotional, social, physical, and spiritual wellbeing.

Key Questions

- How does your context define wellbeing?

- How and why do these definitions align or not align with you own definition of wellbeing?

What is wellness?

The term wellness is often used interchangeably with the term wellbeing (McCallum & Price, 2016). However, Roscoe (2009) argues that wellness is not the same as wellbeing, and instead contributes to it, as wellness is the sum of the positive steps taken to achieve wellbeing.

Key Question

Do you agree with Roscoe’s statement and why / why not ?

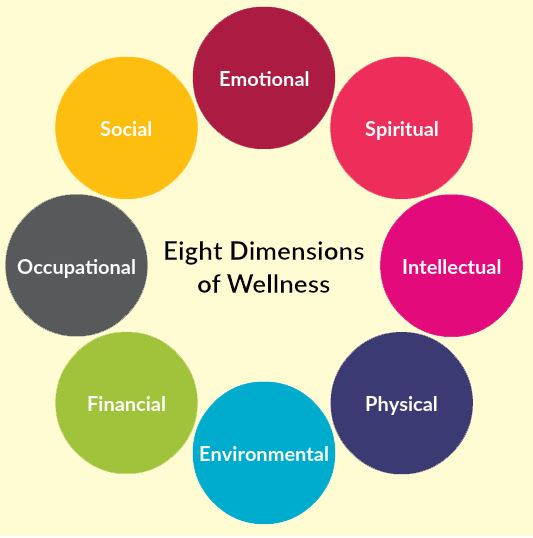

The term wellness was first introduced by Dunn (1959) (as cited in Kirkland, 2014), who argued that health was much more than the absence of disease, and remains the cornerstone of today’s concept of wellness. Dunn defined wellness in terms of the integration of the whole person – the body, mind and spirit, with wellness described as different spiritual, cognitive, emotional, environmental and physical aspects (refer to Figure 2.2), all of which combine to form wellness (Albrecht, 2014).

Roscoe (2009) identified the above core principles of wellness, depicted in Figure 2.2:

- Wellness is dynamic, and changing and evident on many levels.

- A range of factors work in combination to form wellness.

- Wellness emerges from the integrative and dynamic whole rather than from the sum of its parts.

- Environmental contexts impact wellness.

- Life-span developmental changes affect wellness.

- Awareness, education and growth are central to the paradigm of wellness.

Key Questions

- How are definitions of wellness different to, or the same as definitions of wellbeing?

- Where and how does wellness fit into the conceptualisation of wellbeing?

What is mental health?

A similar lack of consensus is also evident when defining mental health. Bhugra, Till and Sartorius (2013) describe mental health as an integral and essential part of overall health which can be defined in at least three ways including: the absence of disease; a balance within oneself and balance between oneself and one’s physical and social environment; and finally a state of being that allows for the full performance of all its mental and physical functions (Bhurga, Dill & Satorius, 2013). Watson, Emery, Bayliss, Boushel & McInnes, 2012) similarly define mental health as a state of being that also includes the biological, psychological or social factors which contribute to an individual’s mental state and ability to function within the environment. The World Health Organisation {WHO} (2007) extends the definition of mental health further to include realising one’s potential; the ability to cope with normal life stresses; and community contributions as core components of mental health. Other definitions also extend beyond this to include intellectual, emotional and spiritual development, positive self-perception, feelings of self-worth and physical health, and intrapersonal harmony as key aspects in defining metal mental (Bhurga et al., 2013).

Key Question

View Figure 2.3 and consider, how does mental health fit into the conceptualisation of wellbeing?

Theoretical conceptualisations of wellbeing

While many theoretical constructs of wellbeing exist, two conceptual approaches to wellbeing research now tend to dominate the field of research and discussion.Objective wellbeing theories tend to define wellbeing in terms of objective, external and universal notions of quality of life indicators such as social attributes {health, education, social networks and connections} and material resources {income, food and housing} (Watson et al., 2012). Objective theories of wellbeing largely arise from Amartya Sen’s work in welfare economics, and tend to focus on agreed core human capabilities necessary for quality life such as body health and integrity; the ability to think and imagine; the ability to express emotions; the ability to exercise practical reasoning and autonomy in contributing to one’s own education, work and political and social participation (Bourke & Geldens, 2007).

In contrast, subjective theories of wellbeing are focused on subjective overall life evaluations, and comprise two main components – affect {feelings, emotions and mood} and life satisfaction, which is identified as a distinct construct and defined relative to specific domains in life {such as school, work and family} (Diener & Ryan, 2009). Affect is dived further into positive and negative emotions, with subjective wellbeing experienced when a predominance of positive emotions occurs more than negative emotions (Diener et al., 1999). As people and perceptions are at the heart of the meaning of subjective wellbeing, Watson et al. (2012) argue that subjective wellbeing has direct utility in describing and facilitating staff and student social and emotional wellbeing. The following contemporary models of wellbeing outline frameworks for exploring wellbeing.

Tripartite Model of Subjective Wellbeing

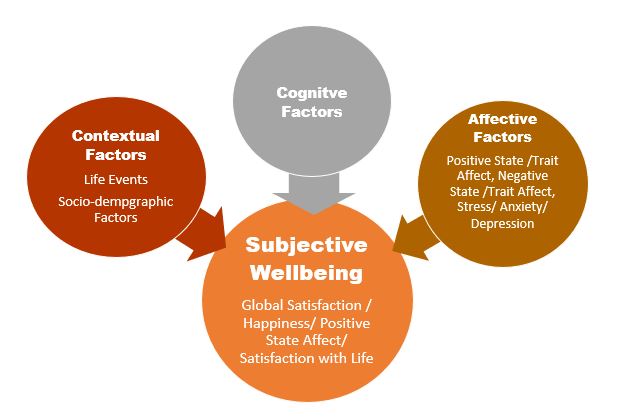

Diener and Ryan’s (2009) Tripartite Model of Subjective Wellbeing (refer to Figure 2.4) presents wellbeing as a general evaluation of an individual’s quality of life in terms of three key components:

- Life satisfaction, which is composed of: Imperfect assessment of the balance between positive and negative affect in one’s life. An assessment of how well one’s life measures up to aspirations and goals;

- Positive affect (pleasurable feelings); and

- Negative affect (painful feelings).

Figure 2.4, a Tripartite Model of Subjective Wellbeing is a representation of the relationship between SWB and cognitive, affective and cultural variables.

Seligman’s PERMA Wellbeing Model

Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model (refer to Figure 2.5) proposes that wellbeing has several measurable elements, each contributing to wellbeing. The PERMA model identifies five essential elements to wellbeing:

- Positive emotions include a wide range of feelings, not just happiness and joy {P}.

- Engagement refers to involvement in activities that draws and builds upon one’s interests {E}.

- Positive Relationships are all important in promoting positive emotions, whether they are work-related, school related, familial, romantic, or platonic {R}.

- Meaning also known as purpose, and prompts the question of “why” {M}.

- Achievement / accomplishment are the pursuit of success and mastery {A}.

McCallum and Price’s Model of Holistic Wellbeing

McCallum and Price (2016) outlined a model of holistic wellbeing where the student is central. They suggest that the model captures the interplay between learner wellbeing, educator wellbeing, and community wellbeing. Six key principles are identified together with six key strategies as the means of enactment in nurturing wellbeing in education.

-

Positive relationships – building and sustaining healthy relationships.

-

Positive strengths – developing and nurturing individual and group strengths.

-

Positive communication – establishing effective and safe communication strategies.

-

Positive behaviour – behaving in a way that welcomes a sense of belonging and connections to others and positive, peaceful and caring action.

-

Positive emotion – nurturing emotional health.

-

Positive leadership – scaffolding wellbeing through growing leaders with a democratic leadership style.

(McCallum & Price, 2016, p. 144).

School community wellbeing

Educational contexts are now key stakeholders in promoting student and staff wellbeing, regardless of the diversity of wellbeing definitions and approaches. McCallum and Price (2016) argue that given the link between wellbeing and academic achievement, educators, policy and curriculum developers, it is no surprise that educational contexts are being increasingly challenged to centre wellbeing as both a foundation to, and integral part of learning. As a result, an increasing an emphasis is now being placed on producing successful and confident learners, resulting in a more holistic approach to education in order to support both academic achievement and wellbeing of students. McCallum and Price (2016) also suggest that wellbeing education is for the whole community and have proposed a Wellbeing education model which supports that notion by suggesting that wellbeing education is an essential provider to academic learning and achievement (McCallum & Price, 2016). We believe that wellbeing education goes beyond this and is essential to the creation of social hope and social capital.

Supportive educational environments must now promote the wellbeing of learners by assisting them to develop a positive sense of identity, agency, self-worth and connectedness within their community. Learners, educators, communities and educational institutions hold responsibility in this regard. Scoffham and Barnes (2011) noted that the challenge for today’s educators is to provide a place as well as programs that are both secure and demanding, and based upon pedagogy that furthers the present and future wellbeing and happiness of the children and young people within positive social and environmental change contexts.

Key Questions

- Has your definition of wellbeing changed or not changed and if so why and how?

- What factors influence your wellbeing definition?

Conclusion

Despite the range of notions encompassed in wellbeing definitions explored throughout this chapter, we believe that wellbeing is experienced differently by different people. We embrace Diener’s (2009) definition that wellbeing consists of three elements that involve the cognitive evaluation of overall satisfaction with life; positive affect; and lower levels of negative affect. Wellbeing can be viewed holistically, in terms of balanced life experience where, wellbeing needs to be considered in relation to how an individual feels and functions across several areas, including cognitive, emotional, social, physical and spiritual wellbeing. As authors we hope that readers are challenged to deeply ponder how they define wellbeing.

As educational contexts are now key stakeholders in promoting children, young people and staff wellbeing, it is no surprise that educational communities are being increasingly challenged to centre wellbeing as both a foundation to, and integral part of an educational context’s structures, processes and learning. The challenge for educational contexts then is to clearly define wellbeing; select or develop a model of wellbeing that promotes the wellbeing of students (children / young people) and staff; and develop a positive sense of identity, agency, self-worth and connectedness.

References

Albrecht, N. (2014). Wellness. The International Journal of Health, Wellness, and Society, 4 (1), 21-36.

Bourke, L. & Geldens, L. M, (2007). Subjective wellbeing and its meaning for young people in a rural Australian centre. Social Indicators Research, 82 (1), 165-187.

Bhugra, D., Dill, A. & Sartorius, N. (2013). What is mental health? International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59 (1), 3-4. doi:10.1177/002076401246331.

Camfield, L., Streuli, N. & Woodhead, M. (2009). What’s the use of ‘well-being’ in contexts of child poverty? Approaches to research, monitoring and children’s participation. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 17, 65-109.

Carter, S. (2016). Holding it together: an explanatory framework for maintaining subjective well-being (SWB) in principals. [Thesis (PhD/Research)].

Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. (2000). ‘The ‘‘what’’ and ‘‘why’’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Diener, E. (2000). SWB: The science of happiness, and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34-43. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.

Diener, E. (2009). Assessing well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. Social Indicators Research Series, 39. New York, NY: Springer.

Diener, E., & Eid, M. (2006). The finale: Take-home messages from the editors. In M. Eid & E. Diener (Eds.). Handbook of multi-method measurement in psychology. (pp. 457-463). Washington, DC:American Psychological Association.

Denier, E. & Ryan, K. (2009) Subjective wellbeing: A general overview. South African Journal of Psychology, 39(4), 391 – 406.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of

Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Suh, M., Lucas, E., & Smith, H. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125 (2), 276–302. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Smith, H., & Shao, L. (1995). National differences in reported subjective well-being: Why do they occur? Social Indicators Research Special Issue: Global Report on Student Well-Being, 34, 7–32.

Dodge, R., Daly, A., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2 (3), 222-235. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

Husain, A. (2008). Horizons of Spiritual Psychology. New Delhi: Global Vision Publishing House.

Kirkland, A. (2014). What is wellness now? Journal of Health Politics, Policy & Law, 39 (5),957-970.

Larsen, R. J., Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). An evaluation of subjective well-being measures. Social Indicators Research, 17, 1–18.

Larsen, R. J. & Eid, M. (2008). Ed Diener and the Science of SWB. In M. Eid &. R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The

science of SWB. New York, NY: Guilford.

Maslow, A, H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

McCallum, F. & Price, D. (Eds.) (2016). Nurturing wellbeing development in education: From little things, big things grow. New York, N.Y: Routledge.

Michalos, A.C (2007). Education, happiness and wellbeing. Paper presented at the International Conference on ‘Is happiness measurable and what do those measures mean for public policy?’ Rome, Italy.

Roscoe, L.J. (2009). Wellness: A review of theory and measurement for counsellors. Journal of Counselling & Development. 87 (2), 216-226.

Scoffham, S. & Barnes, J. (2011) Happiness matters: towards a pedagogy of happiness and wellbeing. Curriculum Journal, 22 (4), 535-548. doi: 10.1080/09585176.2011.627214.

Shah, H., & Marks, N. (2004). A well-being manifesto for a flourishing society. London, UK:The New Economics Foundation.

Sigleman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and wellbeing. New York, NY: Free Press.

Watson, D., Emery, C., Bayliss, P., Boushel, M. & McInnes, K. (2012). Children’s social and emotional wellbeing in schools: A critical perspective. Bristol, UK: The Policy press.

World Health Organisation {WHO}. (2007). The international classification of functioning, disability and health children and youth (ICF-CY). World Health Organization, Geneva.