5 Pragmatic Applications of Embedding an Education Wide Focus on Wellbeing

Susan Carter and Andersen, Cecily

Key Concepts

- Educational contexts communities play a role in supporting wellbeing development in conjunction with academic development.

- Wellbeing requires a whole educational contexts approach where wellbeing is embedded in educational context policies, curriculum, structures and practices, and as a shared responsibility of all stakeholders.

Guiding question

- How is wellbeing enacted and embedded?

Introduction

Given that almost all children attend school or an educational setting (e.g., early childhood centre) at some time during their lives, school and educational setting communities now have an unprecedented opportunity to play a role in supporting wellbeing development in conjunction with academic development. A whole-school or educational setting approach to student wellbeing promotion calls for student wellbeing approaches that are embedded in an education wide focus in policies, curriculum, structures and practices, and as a shared responsibility of all stakeholders (McCallum & Price, 2016). How do we best do this and take into account the diversity of our school or educational setting communities, while supporting and including people? In order to further a positive and proactive approach to promoting wellbeing in educational settings, this Chapter will explore pragmatic applications of embedding an education wide focus on wellbeing.

Key Question

Before exploring approaches to wellbeing, take a moment to consider your own context. How is wellbeing represented within the context’s policies, structures, practices, curriculum and pedagogy?

Approaches to wellbeing

The wellbeing of children and young people remains a concern both nationally and internationally, with an increasing focus of wellbeing policy, programs, and teacher professional development (Anderson & Graham,2016). Supporting wellbeing is now central to the business of educational contexts. However, as Barry, Clarke and Dowling (2017) note, the challenge for educational contexts and education system leaders lies in integrating evidence-based approaches that promote children and young people’s social and emotional wellbeing and staff wellbeing, and that are sustainable and embedded into the everyday practice of educational contexts. Approaches to wellbeing can be categorised as: positive psychology approaches; health and physical approaches; social and emotional learning approaches; character development and values approaches; relational approaches; and an inclusive approaches as shown in the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing model.

Positive psychology approaches

There has been a rapid growth in positive psychology approaches within educational communities, resulting in a number of associated practices now making their way into educational classrooms and settings all over the world (Ciarrochi, Atkins, Hayes, Sahdra & Parker, 2016). Positive psychology approaches focus on promoting optimal functioning and wellbeing by utilising “psychological discourse and its offshoot school-based training programs, which stress happiness, self-improvement and wellbeing” (Reveley, 2016, p.538). Positive discourse approaches promote a conscious reflexive subjectivity; a focus on self and self-regulation; the use of creative ‘psychological flexibility’; and ‘mindfulness’; as a means to wellbeing (Revelely, 2016; Kashdan, 2010).Burckhardt, Manicavasagar, Batterham, and Hadzi-Pavlovic (2016) proport a viewpoint that such positive psychological approaches to wellbeing are more productive, in that emphasis is placed on prevention and early intervention, rather than reactive intervention in response to “maladaptive emotion regulation strategies that correlate with poor wellbeing” {e.g., depression, anxiety} (p.41).

Emerging from these approaches are a wide range of strategies that can be used within school communities to reduce distress, manage stress, improve mental health and wellbeing.

- Programs developing skills in assertiveness, decision making, coping, relaxation, confidence, organisation and persistence, in addition to cognitive reframing (Waters, 2011).

- Mindfulness training with a focus on intention {understand personal purpose}, attention {to focus and pay attention, to be non-judgmental, to focus on the present and be receptive to one’s mind and body’s reactions, feelings, sensations and thought} and attitude (McCallum & Price, 2016).

- Explicit resilience training (McGrath & Noble, 2012).

- Individual wellbeing strategies such as:

- Reflection strategies for insight into personal practice and / or behaviour.

- Building supportive networks or learning communities.

- Growth mindset approaches to solving problems.

- Self-care practices to restore wellbeing when needed.

- Celebrating achievements and success (McCallum, Price, Graham & Morrison, 2017).

According to Hayes and Ciarrochi (2015), effective implementation of educational context wide positive psychology approaches that promote wellbeing are underpinned require five key actions including:

- The establishment of contexts that empower individuals to clarify their values and choose value-consistent behaviours.

- Assisting individuals to utilise language to successfully and appropriately engage in varying contexts.

- Supporting individuals to acquire resources and skills via exploration and apply these to varying contexts.

- Assisting individuals to gain awareness of their inner and outer experiences and to appreciate their current context and choices.

- Helping individuals to develop understand the ‘self’ and the perspectives of others.

However, it is worth noting that while research shows that positive psychology approaches (Ciarrochi, Parker, Kashdan, Heaven, & Barkus, 2015; Garland, Fredrickson, Kring, Johnson, Meyer & Penn, 2010) and school community positive education interventions have been shown to produce positive benefit (Waters, 2011), positive psychology has been criticized for being “decontextualized and coercive, and for putting an excessive emphasis on positive states, whilst failing to adequately consider negative experiences” (Ciarrochi et al., 2016, p.1).

Health and physical approaches

Good health in addition to regular participation in physical activity has been well recognised as having a positive impact on many aspects of children and young people’s health (Janssen and LeBlanc, 2010). Furthermore, Liu, Wu and Ming (2015) found that the educational contexts are some of the most effective settings in which to improve health and wellbeing outcomes and is consistent with the view that educational communities can create opportunities for stimulating and supporting all children and young people to be more physically active (Holt, Smedegaard, Pawlowski, Skovgaard & Christiansen, 2018; Naylor & McKay, 2009).

The following approaches have been widely utilised to address the health and physical education dimensions of wellbeing, in addition to the basic needs of children and young people (Naylor & McKay, 2009).

- Breakfast Clubs.

- After educational context / school care programs.

- Programs that provide assistance with shelter, clothing and care.

- Strategies to improve child protection and safety.

- Programs focussing on physical fitness, active lifestyles, healthy eating and self-esteem development.

- Programs focusing on safe and responsible choices and avoidance of harmful situations and substances.

- Strategies and programs to protect against bullying and being safe on line.

Carlsson, Rowe and Stewart (2001) identified that wellbeing was promoted in educational contexts when three key actions were in place.

1. Curriculum, teaching and learning that encompassed a holistic view of health and the development of more generic life skills such as decision making, effective communication and negotiation skills (Carlsson et al.,2001).

2. Whole of educational context ethos, environment, structures, organisation, policies and planning that support and reinforce health messages that are taught in the formal curriculum (Carlsson et al.,2001).

3.Commitment and collaboration within an educational context’s community to develop a shared vision and create strategies to address the physical and health needs of the whole educational context (Carlsson et al., 2001; McCallum & Price, 2016).

Social and Emotional Learning approaches

Greensburg, Domitrovich, Weissberg and Durlack (2017) argue that evidence-based Social and Emotional Learning {SEL} programs, when implemented effectively have potential to promote measurable and long-lasting improvements in the lives of children and young people. SEL approaches have a focus on contributing to wellbeing by developing responsibility, social skills and emotional management strategies which enhance children and young people’s “confidence in themselves; increase their engagement in school, along with their test scores and grades; and reduce conduct problems while promoting desirable behaviours” (Greensburg et al. 2017. p.13).

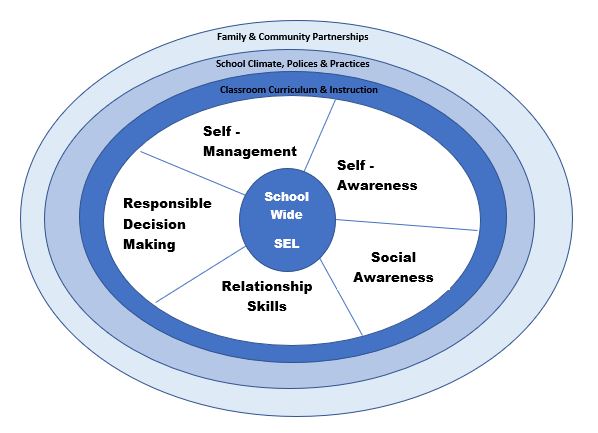

SEL program promote wellbeing by teaching students specific SEL skills in order to create a classroom and educational context culture that enhances and enables SEL skills (refer to Figure 5.2).

There are five core elements of the model: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making.

- Competence in self-awareness which involves understanding your own emotions, values, and personal goals {knowing own strengths and limitations, a sense of self- efficacy; optimism; a growth mindset; ability to recognise how own thoughts, feelings, and actions are connected} (Greensburg et al. 2017).

- Competence in self-management which encompasses regulation of own emotions and behaviours; the ability to delay gratification; manage stress; control impulses; and persevere through challenges.

- Competence in social awareness describes the ability to take the perspective of people with different backgrounds or from different cultures; empathize; act with compassion toward others; understand social behaviour norms} (Greensburg et al., 2017).

- Relationship skills involves the establishment and maintenance of healthy and rewarding relationships and includes the ability to act in accordance with social norms {communicating clearly, listening actively, cooperating, resisting inappropriate social pressure, negotiating conflict constructively, and seeking help when needed} (Greensburg et al., 2017).

- Responsible decision-making is outlined as utilising the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to make constructive choices.

Character development and values approaches

The last decade has seen a growth in interest in use of character development and values approaches within educational contexts as mechanisms for promoting wellbeing (Smith, 2013). Character development and values approaches foster important core, ethical and performance values such as caring, honesty, diligence, fairness, fortitude, responsibility, and respect for self and others as a means of affecting wellbeing (Quinlan, Swain & Vella-Brodrick, 2012). Both styles of approach support wellbeing through a focus on character strength training processes; by understanding and reflecting on values; and reflecting values in one’s own attitudes and behaviour. However, Linkins, Niemiec, Gillham and Mayerson (2015) argue that this approach tends to be more prescriptive in nature than other previously discussed approaches, and views character and values as an” external construct that needs to be instilled within the individual {rather than an innate potential to be nurtured}” (p.64).

Relational approaches

According to Correa-Velez, Gifford and Barnett (2010), relational approaches provide opportunities for children and young people to feel connected; to feel that they belong; and to feel that they are cared for. The ability of children and young people to connect has been shown to be a key protective factor in lowering health risk behaviour while concurrently increasing positive wellbeing (McCallum & Price, 2016). Relational approaches to supporting wellbeing focus on supporting wellbeing through programs and initiatives that focus on:

- Relationships that are positive and productive engagements between children/young people teachers and peers.

- Belonging where a sense of membership of the educational context is experienced.

- Inclusion where a sense of being included in the educational context’s school culture, structure and processes.

- Active participation which describes the extent to which children and young people feel that they participate in, and exercise voice in relations to a educational context’s activities ad affairs (Aldridge, Fraser, Fozdar, Ala’I, Earnest & Afari, 2016). Interestingly, Fattore, Mason and Watson (2012) report that students who were provided with an opportunity to have their say and have their opinions taken seriously, demonstrated higher levels of wellbeing than student without an opportunity to have their say.

Approaching wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

As authors working at the University of Southern Queensland (USQ) we acknowledge the Giabal and Jarowair peoples of the Toowoomba area, the Jagera, Yuggera and Ugarapul peoples of Ipswich and Springfield, the Kambuwal peoples of Stanthorpe and the Gadigal peoples of the Eora nation, Sydney as the keepers of ancient knowledge where USQ campuses and hubs have been built and whose cultures and customs continue to nurture this land. USQ also pays respect to Elders – past, present and future. Further, we acknowledge the cultural diversity of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and pay respect to Elders past, present and future. Finally, we celebrate the continuous living cultures of First Australians and acknowledge the important contributions Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have and continue to make in Australian society.

Please take a moment to listen to why we need to acknowledge its traditional custodians.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience considerably more widespread social disadvantages and poor health (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018) than any other Indigenous population in the developed world, and alarmingly these outcomes are similar to Third World countries (Kingsley, J., Townsend, M., Henderson-Wilson, C., & Bolam, 2013; Carrington, Sheperd, Jianghong & Zubrick, 2012). Kingsley et al. (2018), suggest that evidence indicates that such inequalities can be better understood by focusing on a range of factors including the impact of colonisation, intergenerational trauma, cultural and social determinants of health, and by considering holistic ideas of wellbeing. Kingsley et al. (2018) also argue that current notions of indigenous wellbeing should be challenged. Therefore, educational contexts have a role to play in enacting change in addition to improving the wellbeing outcomes for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students guided by the National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017-2023 (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council {AHMAC}, (2017).

Addressing wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples requires understanding contexts (Fossey, Holborn, Abawi, & Cooper, 2017}, Understanding Australian Aboriginal Educational Contexts); Understanding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perspectives recognising human rights, the strength of family and kinship groups, and traditional lifestyles, language, and geographical places.

As authors we recognise and support the points raised by Alderete (2004) that the notion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples wellbeing should not only be linked to a set of standards or measurable indicators that are easy to implement for government reporting purposes and requirements. Instead, wellbeing indicators should also include nuances that capture the numerous positive, protective enduring elements, connected with Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples’ ways of life (Prout, 2012). Biddle and Swee (2012), identified that there are many instances and examples in literature on Indigenous peoples that highlight the positive relationship between the sustainability of Indigenous land, culture and language and an Indigenous person’s wellbeing.

There are things you can be mindful of to make your support more meaningful for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples who may be struggling with their wellbeing. Panelli and Tipa (2009) suggest providing a culturally safe environment embedded with positive social relationships, being respectful of culture with connection to Country, kinship, traditional knowledge, and identity, and being supportive of physical, social, and spiritual needs helps foster wellbeing. We also encourage you to involve family, carers, or other community members in providing positive support.

Key Questions

Considering the points raised by Panelli and Tipa (2009) that providing a culturally safe environment embedded with positive social relationships, being respectful of culture with connection to Country, kinship, traditional knowledge, and identity, and being supportive of physical, social, and spiritual needs helps foster wellbeing.

- What is being done in your context to ensure that this occurs?

- How do you define family?

- How do you involve family, carers, or other Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples to provide positive support?

An inclusive approach

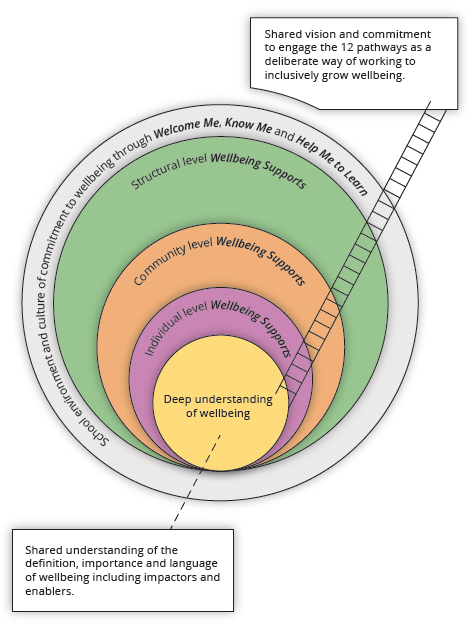

An inclusive approach synthesises elements of positive psychology, health and physical; social and emotional learning, character development and values, and relational approaches into one approach as educational contexts are expected to addresses all of these components we thought the approach to wellbeing needed to also be responsive to the contemporary educational context content. We present a model to depict the approach as shown below in Figure 5.3 Growing Inclusive Wellbeing.

The model ‘Growing Inclusive Wellbeing’ depicts five components, represented visually as circles in order to highlight the layers of knowledge, understanding and enactment through pathways that are embedded: the inner circle; an individual level; community level; structural level; and the educational context environmental culture.

The inner circle

The inner circle, Deep Understanding of Wellbeing, represents the development of a whole educational context community understanding of wellbeing, including the enablers and impactors that are present within the content. As authors we suggest that every individual experiences wellbeing differently and as such embrace the definition put forward by Diener, Oishi, and Lucas (2003) to be “people’s emotional and cognitive evaluations of their lives, includes what lay people call happiness, peace, fulfilment, and life satisfaction” (p. 403). People’s views and definitions of SWB (commonly referred to as wellbeing) are personal and dependent upon how each individual evaluates their life (Carter 2016).

The three levels of wellbeing support

The next three circles in the diagram, depict factors that have an influence on wellbeing across all populations and these can be categorised into three key sections: Individual Level Wellbeing Supports; Community Level Wellbeing Supports; and Structural Level Wellbeing Supports.

- Individual Level Wellbeing Supports – an ability to deal with thoughts and feelings; emotional resilience; ability to cope with stressful or adverse circumstances; a sense of self; and the development of social skills.

- Community Level Wellbeing Supports – a sense of belonging, social support and community participation.

- Structural Level Wellbeing Supports – social, economic and cultural factors that are supportive of wellbeing. For example: quality of housing, access to health and social services and education, political and justice systems.

The outer circle

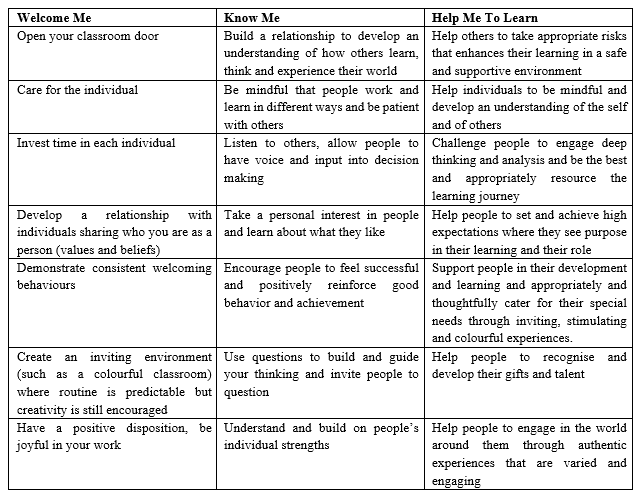

The out circle encapsulates what is happening throughout an educational context in embedded practice, showing the School Environment and Culture of Commitment to wellbeing through ‘Welcome Me, Know Me and Help Me to Learn’. An educational context’s environment is reflective of all that happens within the context’s community and it can be seen, heard and felt, often through nuanced experiences. Table 5.1 highlights key components of ‘Welcome Me, Know Me and Help Me to Learn’.

12 key pathways to embedding an education wide focus on wellbeing

Figure 5. 3 outlines 12 pathways to embedding an education wide focus on wellbeing. Building on, and adapting Noble, McGrath, Wyatt, Carbines and Robb’s research (2008), we suggest that there are twelve key pathways that are essential in determining an educational context’s contribution to embedding wellbeing within a context’s community, in addition to identifying specific practices that educational contexts can put in place to enhance wellbeing: expert context leadership; strategic visioning; quality teaching and learning; a supportive, caring and inclusive educational context; a safe learning environment; social and emotional competencies; a sense of meaning and purpose, including engaging student voice; using, monitoring and evidencing strengths-based approaches; strategies encouraging a healthy lifestyle; programs to develop pro-social values; family and community partnership; and spirituality.

-

Expert inclusive leadership

The promotion of student, staff and community wellbeing, through effective inclusive leadership which:

- Empowers individuals and educational contexts to take responsibility for both their own wellbeing and that of others (Powell & Graham, 2017).

- Systematically monitors of student and staff wellbeing in order to:

- Evaluate the impact of initiatives (Weare & Nind, 2011).

- Plan for future activities (Weare & Nind, 2011).

- Promotes staff development, health and wellbeing by providing:

- Access to professional development to increase personal knowledge of emotional wellbeing, and to equip staff to be able to identify mental health and wellbeing issues in their students (Price & McCallum, 2015; 2016).

- Clear referral processes and pathways to a range of relevant in and out of context support strategies, structures and agencies for both staff and students (Weare & Nind, 2011).

- Opportunities for assessing and supporting the emotional health and wellbeing needs of staff (McCallum & Price, 2010).

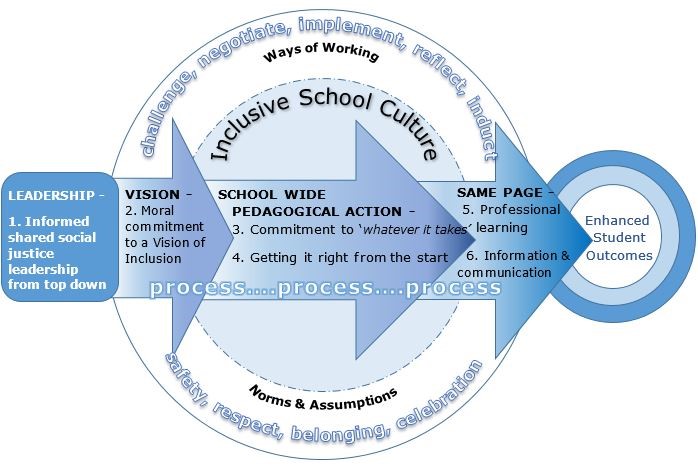

One way of enabling inclusive leadership is through the six principles of inclusion captured in the model ‘A Conceptual Model of the cultural indicators of an inclusive school‘ (Abawi, Carter, Andrews & Conway, 2018) {Figure 5.4 below}.

-

Strategic visioning

Educational context communities that have a clear meaningful and strategic vision promote the commitment of all members to pursue their work with energy, self-discipline, collaboration and a keen sense of purpose (Fullan, 2010). Strategic visioning is a guiding process that is essentially concerned with forward thinking which draw upon the beliefs, goals and the environment within an educational context, and “if done correctly should be the backbone of a positive and inspiring system” (Bainbridge, 2007, p.1). The longer term benefits are significant and very real, as strategic visioning can assist an educational context’s community to “break free from convention and encourage thinking ‘outside the box’” (Bainbridge, 2007, p.3).

By clearly defining an educational context’s direction and purpose, a strategic vision alerts all with the context’s community where efforts should be directed in addition to aligning resources and effort towards common goals. A strategic vision should be underpinned by a shared philosophy that every child has a right to learn and every child is capable of learning and should be given the opportunity to actively participate in all facets of school life (Carter & Abawi, 2018). It also provides a safe environment where new ideas can be encouraged, and new ways of working investigated in a safe and secure process.

Key Questions

- How and why does strategic visioning contribute (or not contribute) to wellbeing within your context?

- Do all members of your context accept responsibility for developing and sustaining wellbeing?

- Are all members of your educational context community encouraged to actively participate in developing, implementing, and / or evaluating wellbeing in your context?

3. Quality teaching and learning

Quality teaching and learning involves the provision of varied, engaging and inclusive high-quality pedagogy which:

- Focuses on the enhancement of student engagement with learning.

- Uses cooperative learning and other relational teaching strategies.

- Explicitly teaches skills and understandings related to personal safety, protective behaviours, values and social and emotional skills, and integrates this learning into the mainstream processes of educational context life (McCallum & Price, 2016).

- Provides early intervention and targeted student support for children and young people already showing signs of social, emotional and behavioural problems, or are at greater risk of experiencing poorer mental health (Powell & Graham, 2017).

Key Question

Do all members of your context accept responsibility for developing and sustaining supportive teaching and learning that supports wellbeing?

4. A supportive, caring and inclusive educational context community

Noble et al., (2008) suggest whole school community approaches must promote an ethos and conditions for a supportive, caring and inclusive community. We have built upon the conditions to include:

- feeling welcomed, valued, respected and free form discrimination and harassment (Cahill & Freeman, 2007);

- having a sense of connectedness and are provided with opportunities to develop deep personal connections with other individuals and groups (Acton & Glasgow, 2015);

- creating a sense of belonging;

- treating people fairly;

- feeling included;

- experiencing mutual respecting (Abawi, Andersen & Rogers, 2019).

- acknowledging and respecting diversity (Carter, S. 2019)

- demonstrating a positive view of self and having their identity respected (Noble et al., 2008).

- experiencing positive peer and adult relationships which have an affirmative influence on wellbeing, and which in turn contributes to satisfaction, productivity and achievement (McCallum, Price, Graham & Morrison, 2017).

- experiencing positive learning behaviours (Jamal, Fletcher, Harden, Wells, Thomas & Bonell, 2013).

- respecting culture with connection to Country, kinship, traditional knowledge, and identity (Panelli &Tipa, 2009).

5. A safe learning environment

An emotionally secure and safe environment with development and application of ‘Safe Schools’ policies and procedures which:

- promotes positive safe and responsible behaviour, respect, cooperation and inclusion (Abawi, Andersen & Rogers, 2019);

- “prevent[s] and manage putdowns, bullying, and violence and harassment threats.

- nurture and encourage student’s sense of self-worth and self-efficacy.” (Noble et al.,2008, p.12);

- uses effective and safe communication strategies (McCallum & Price, 2016);

- promotes productive and safe use of technologies {cyber safety} as an enabler which supports wellbeing, relationships and health, rather than focusing on negative impacts of social media and online platforms (Spears, 2016);

- creates a culturally safe environment embedded with positive social relationships (Panelli & Tipa, 2009);

- supports everyone to feel safe.

When people feel safe and have this basic need satisfied they are more able to concentrate on learning tasks.

Key Questions

- Is being safe and supported acknowledged as being essential for student and staff wellbeing within your context? If so why, how and how often?

- How does trust, belonging and mutual respect contribute (or not contribute) to wellbeing in your context?

- How does (or does not) a positive sense of inclusiveness and/ or identity contribute (or not contribute) to wellbeing in your context?

6. Social and emotional competencies

Social and emotional competencies enable individuals to learn how to solve problems, manage feelings, manage friendships, promote the ability to cope with difficulties, relate to others, resolve conflict, and feel positive about themselves and the world around them.

By increasing social and emotional competence an individual’s capacity to cope and stay healthy is increased (McCallum & Price, 2016) in spite of the negative factors that happen through life as the social and emotional competencies act as buffers to wellbeing depletion (Carter, 2016). Noble et al. (2016) suggest that social and emotional competencies include being resilient, being able to cope with difficult and stressful situations and events, engaging in positive and optimistic thinking, having self-awareness, setting and achieving goals, developing successful relationships and making decisions. McCallum and Price (2016) add competencies such problem-solving, conflict management and resolution, the ability to work collaboratively, and the development of self-help skills that enable individuals to utilise their own efforts and resources to achieve wellbeing. Weare and Nind (2011) extend social and emotional competencies even further by including an understanding of, and managing feelings, and an understanding of, and management of relationships with parents / carers, peers and teachers.

7. A sense of meaning and purpose

Provision of as many opportunities as possible to participate in the educational context and the wider community in order to develop a sense of meaning or purpose including:

- Tasks that are worthwhile

- Service within the community.

- Civic responsibly and participation.

- Leadership within an educational context

- Contribution to the educational community.

- Providing peer support.

- Opportunities for student voice where student voice is valued and invited.

- Engaging in activities that focus on the exploration of spirituality (Noble et al., 2008).

Engaging student voice is important. Sometimes within schools, conversations about student wellbeing and mental health can often occur without discussions with students themselves about these issues (Heysen & Mason, 2014). Substantial research points to the benefits and value of involving children and young people in decision making, as well provision of their points of view (Bessell, 2011). Research by Simmons, Graham and Thomas (2015) revealed just how capable students were in “providing rich, nuanced accounts of their experience that could potentially inform school improvement” (p.129), with students often “identifying creative ways that pedagogy, the school environment and relationships could be improved, changed or maintained to assist their wellbeing” (p.130). The voice of students within schools should then be a central part of our conversations and plans as we “work out how to nurture happy, balanced kids by actively engaging with students…. about matters that concern them” (Heysen & Mason, 2014, p.15). Such findings highlight the importance of student voice as a democratic, participatory and inclusive approach in schools.

Key Questions

- Is social and emotional learning explicitly taught in your context? If so what, why, how and how often?

- How does (or does not) a sense of meaning and purpose contribute (or not contribute) to student and staff wellbeing in your context?

8. Using, monitoring and evidencing strengths-based approaches

Using a strengths-based approach involves educators discovering, developing and harnessing their own talents, and maximising these in the work domain to remain current in their field, implement innovative curriculum in ways that meet the needs of all their learners and to utilise feedback to continue to improve their performance. Teachers can also inspire students to discover, harness and maximise their own talents. Noble et al., (2008) suggest the adoption of a strengths-based approach to organisation, curriculum and planning should:

- Cater for the diversity of student character strengths.

- Cater for and extend all student intellectual levels.

- Value, develop and use in a meaningful way, the individual and collective strengths of students, teachers and parents.

Consider how you do this and also how you evidence that it has occurred, including listening to and responding to feedback in order to improve your practise.

9. Strategies encouraging a healthy lifestyle

A healthy life style approach is one that explicitly teaches students the knowledge and skills needed for a healthy and self-respecting life-style, and the support to apply the skills and knowledge to their own lives. This includes a focus on:

- Good nutrition.

- Fitness and exercise.

- Avoidance of illegal drugs, alcohol and other self-harming actions and situations.

Consider ways that encouraging a healthy lifestyle can be explicitly evidenced in your practice.

10. Programs to develop pro-social values

Within schooling systems there are a number of programs that develop pro-social values. According to Nobel et al. (2008), pro-social values programs explicitly teach and model values such as honesty, respect, compassion, fairness, responsibility and acceptance of difference, in addition to providing practical opportunities to put values into practice within an educational context and the wider community. Consider what your community values and how reflective these values are of an inclusive and multicultural society as well as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives. How do you evidence that inclusive pro-social programs are occurring n your context?

Key Questions

- Are strength-based approaches used within your context? If so, who are they used with, and how and why do they contribute (or not contribute) to wellbeing within your context?

- Are strategies encouraging healthy lifestyle used within your context? If so, who are they used with, how and why do they contribute (or not contribute) to wellbeing within your context?

- Are pro-social values explicitly taught in your context? If so what, why, how, and how often?

11. Family and community partnerships

Well implemented interventions that support school and classroom strategies for developing:

- Positive teacher-student relationships (Anderson & Graham, 2016).

- Positive peer relationships (Cemalcilar, 2010).

- Positive school-family and school-community relationships (Cemalcilar, 2010).

Students are engaged through avenues that encourage:

- student voice (Anderson & Graham, 2016); and

- authentic involvement in learning, decision making and peer-led approaches (McCallum & Price, 2016).

Parents/carers are also engaged in genuine participation, particularly families that may feel blamed and/ or stigmatized (Weare & Nind, 2011). This engagement is nuanced as it depends on interests, skillsets and abilities. A challenge for schools is to ensure that they have inclusive ways of engaging and harnessing voices that may present differing views or needs, including those of students with disabilities, and Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander peoples (our first peoples). Listening to a voice is the first step but importantly it is about valuing diverse perspectives and engaging in meeting the learning needs of all students, teachers and educational leaders in the context. Giving students a voice is important and suggests student-centred teaching practices that place emphasise on a student’s interests in a manner where the student feels valued (Waters, 2017). One way of doing this could be the creation of a Student Council where students are elected by their peers, participate in informed decision making, and are empowered as advocates to have a valued voice in what impacts them. If this is what the school has chosen, we encourage you to look at the students selected and consider the diversity of the group. Is there a representative for students with disabilities? Is there a representative for Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander students? We suggest that schools think creatively of ways to engage as many schools employ a parent liaison officer to help create and maintain parent engagement (Carter & Creedon, 2019) but further, we encourage you to think reflectively about whether the stakeholder groups do all actually have a voice.

12. Spirituality

Spiritual wellbeing is considered by many to play an important part in the promotion of general wellbeing, health and quality of life. Eckersley (2007) defines spirituality as “a deeply intuitive, but not always consciously expressed sense of connectedness to the world in which we live” (p. 54), with wellbeing arising from the web of relationships and interests that arise from that connectedness. De Souza (2009) suggests that the term spirituality is inclusive of a myriad religions and encompasses the notion of connection to a higher being. Grieves (2006) argues that spirituality is a starting point for wellbeing, and is understood and experienced within a social, natural and material environment, which based upon the cultural understandings that people have developed to enable them to interact with their world.

As consequence, Yust, Johnson, Sasso, and Roehlkepartain (2006) argue that spirituality plays a role in the wellbeing of both students and staff, with spirituality being the factor in human life that nurtures and gives expression to the inner and outer lives of students and staff, which in turn promotes balance and wellbeing. A study by Dobmeier and Reiner (2012) identified the following mechanisms for developing spirituality within an educational context:

- Reading spiritual autobiographies (Curtis & Glass, 2002).

- Engaging in role plays which challenge thinking and discussion (Briggs & Dixon-Rayle, 2005).

- Using reflective journaling.

- Teaching the techniques of focusing, forgiveness, and meditation (Curtis & Glass, 2002).

- Being exposed to a rage of panel presentations/guest speakers who reflect on their own life journeys.

- Exploring spiritual readings (Briggs & Dixon Rayle, 2005).

- Engaging personal narratives.

- Engaging hermeneutics focuses on identifying and applying sound principles of biblical interpretation, as it is both a process of action and reflection (Carter, 2018).

- Self-exploration (Boyatzis, 2009).

- Talking with pastoral counselors about focused spirituality topics (Boyatzis, 2009).

- Respecting spiritual connection to Country (Panelli &Tipa, 2009) and Aboriginal spirituality (Grieves,2008).

Key Questions

- Do family and community partnerships support wellbeing within your context? If so, who are they used with, and how and why do they contribute (or not contribute) to wellbeing within your context?

- Is spirituality addressed within your context? If so, how is addressed and how does it contribute (or not contribute) to wellbeing within your context?

Wellbeing Resources

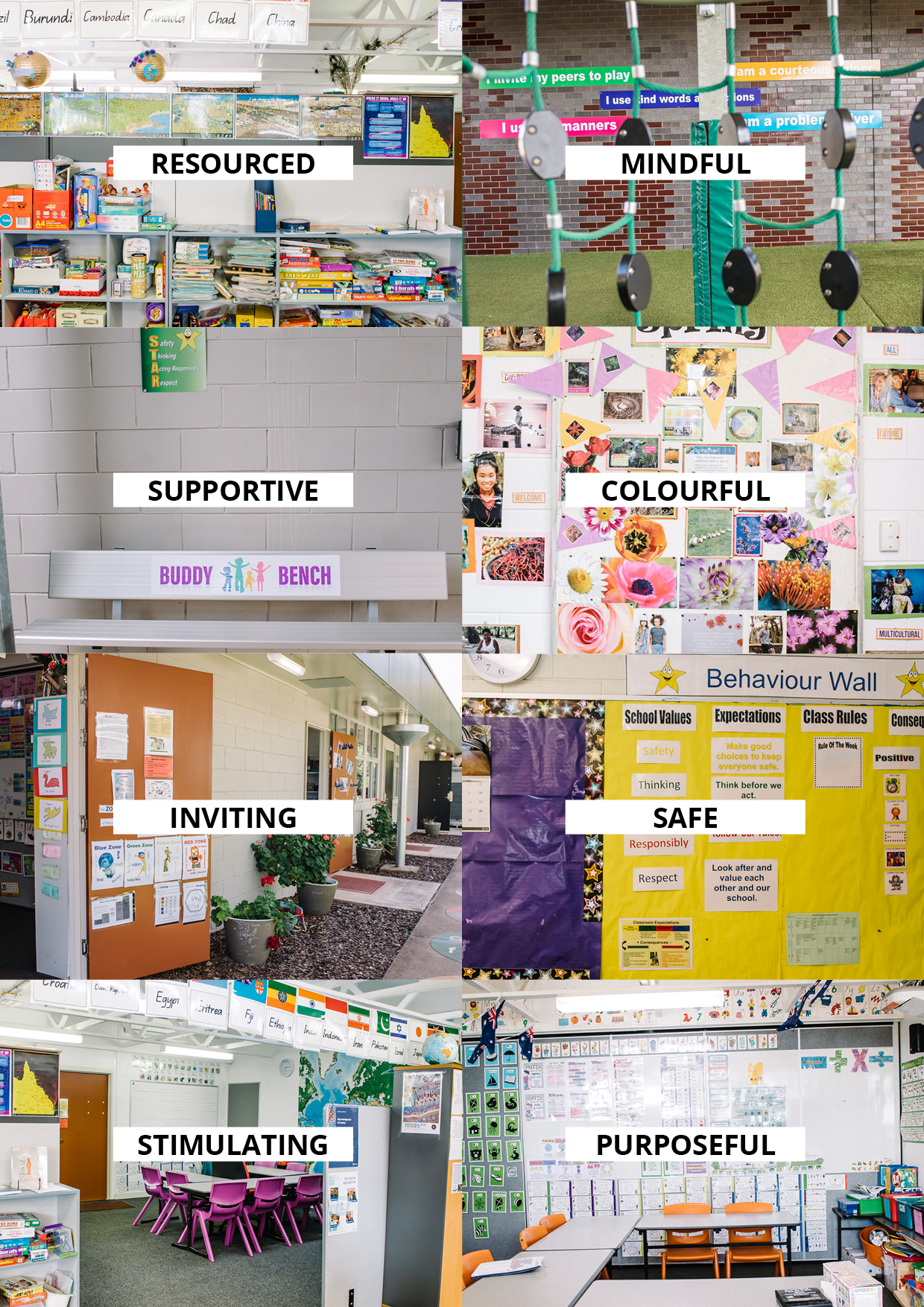

As part of the focus on wellbeing we encourage educational contexts to regularly collect evidence of their practice. Figure 5.4 below features a snapshot of evidence of how students are supported and engaged in their learning and we know from research that this helps to contribute to a feeling of context connectedness and belonging which is strongly linked to positive wellbeing.

Conditions for success

Educational contexts are faced with the challenge of creating a space to talk about, model and encourage healthy eating, appreciating the peaceful moments and the beauty of the world, and taking the time to exercise.

There is clear consensus in the literature regarding the importance of healthy eating. Nutrition is a component that now features in discussions regarding school lunches, tuckshop menus and access to appropriate foods along with education about nutrition. The challenge for educational contexts is for staff to model healthy eating and good nutritional practices, the educational contexts to understand what healthy eating is, and to embed a focus on good nutritional practices in the day to day educational context community language and ways of working.

Teach children and young people to just take a moment to appreciate the simple pleasures, the depth of colour in the sky, the sound of the birds, the movement of the wind, the clever design of the dandelion seeds floating on the wind, and the natural beauty of our planet. We suggest you explicitly ask children and young people to note the peaceful moments and the peaceful images, and to draw attention to the positive elements in their daily lives by connecting to the land we inhabit.

Research suggests that exercising is good for people and contributes to feelings of positive wellbeing. What does this mean for educational contexts that are committed to fostering wellbeing? We suggest that educational contexts need to discuss what this looks like in practice for their context and community, and how the context’s practices can cater for diversity of interest, culture, religion, and ability while maximizing available resources.

In order for an education wide focus on wellbeing to be successfully embedded, the following conditions are required in order to create effective implementation and sustainability of whole of educational context wellbeing initiatives:

- Shared vision and understanding of the concept of wellbeing and shared ways of working to implement the vision.

- Commitment from the whole educational context’s community, not just the leader or leadership team (McCallum & Price, 2016).

- A clear and widely understood shared language and consistent processes for wellbeing across the whole educational context’s community (Powell & Graham, 2017).

- A clearly identified student voice.

- Broad collaboration with the whole educational context’s community (McCallum & Price, 2016).

- A shared moral purpose generated by the stakeholders and communicated widely within the educational context, created purpose, good communication and a sense of ownership of any wellbeing initiatives (Noble et al., 2008).

- Use of ongoing formal and informal teacher professional development including the involvement of acknowledged experts Noble et al., 2008). We also suggest that teacher aides and volunteers are included in professional development opportunities in order to create a school wide shared language and way of working with wellbeing.

- Fore fronting and promotion of student wellbeing as being a priority across the whole educational community (Noble et al., 2008).

- Explicit teaching of values such as respect, cooperation support and social and emotional learning skills that facilitate and encourage classroom participation, positive interactions with teachers/peers and good study habits (Noble et al., 2008).

- Clear expectations of behaviour which are modeled and positively reinforced with shared celebratory moments.

- Ongoing and consistent support from school leadership (Noble et al., 2008).

- Use of engaging and inclusive pedagogical approaches (Noble et al., 2008) and innovative strategies that cater for student needs and offer opportunities for extension for all learners.

- Explicit links made to the goals of the educational context and the system with students, teachers and the school community having a clear shared understanding that everyone can succeed and will be supported to do so.

- Processes in place to ensure and encourage a high participation of all students in wellbeing initiatives.

We strongly support the suggestion by Noble et al. (2008), stressing the importance of appointing a wellbeing coordinator or team to oversee the implementation of any wellbeing initiatives. We also suggest that it is important to analytically and critically review practice to know when initiates are effectively achieving the desired outcomes or when change is required so that informed decision-making can occur.

Key Question

Consider the different perspectives that you need to take into account:

- What does high participation look like, feel like and sound like for people with disabilities, learning difficulties, English as second language or dialect, first peoples, gifted and talented students, indeed for all individuals? How do you evidence that this is occurring?

Conclusion

We, together with McCallum and Price (2016) argue that even though academic achievement continues to be a high priority within educational contexts, addressing wellbeing across the whole educational community as well as in the learning environment, curriculum, pedagogy, policies, procedures and partnerships domains, is of upmost importance.

By investing in whole of educational context wellbeing programs and initiatives in conjunction with academic development, Scoffham and Barnes (2011) likewise argue that there will be significant benefits not only for student wellbeing, but also to student achievement, teacher wellbeing and productivity. Wellbeing then requires a whole educational context approach, where wellbeing is embedded in a context’s policies, curriculum, structures and practices, and as a shared responsibility of all stakeholders. This Chapter has endeavoured to grow thinking about wellbeing behaviour and ecology, as well as highlighting a way of evidencing and supporting wellbeing growth, emphasising the importance of aligning the values of an educational context, and ways of working, with the pathways that help enable wellbeing.

References

Abawi, L., Andersen, C. & Rogers, C. (2019). Celebrating diversity: Focusing on inclusion. In S. Carter (Ed), Opening Eyes onto Diversity and Inclusion. Toowoomba Australia, University of Southern Queensland.

Abawi, L., Carter, S., Andrews, D., & Conway, J. (2018). Inclusive schoolwide pedagogical principles: cultural indicators in action. New Pedagogical Challenges in the 21st Century: Contributions of Research in Education, 33. doi:10.5772/intechopen.70358

Alderete, E. (2004). The importance of statistics on Indigenous Peoples for policy formulation at national and international levels. United Nations Workshop on data collection and disaggregation for Indigenous Peoples, PFII/2004/WS.1/4, New York.

Aldridge, J.M., Fraser, B.J., Fozdar, F., Ala’I, K., Earnest, J. & Afari, E. (2016). Students’ perceptions of school climate as determinants of wellbeing, resilience and identity. Improving Schools, 19 (1), 5-26. doi: 10.1177/1365480215612616

Anderson, D.L. & Graham, A.P. (2016). Improving student wellbeing: Having a say at school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27 (3), 348-366. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2015.1084336

Australian Bureau of Statistics {ABS}. (2018). Population Characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Publications Service. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-Peoples

Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council {AHMAC}. (2017). National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ mental health and social and emotional wellbeing. Retrieved from https://pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/mhsewb-framework_0.pdf

Bainbridge, S. (2007). Creating a vision for your School: Moving from purpose to practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Barry, M.M., Clarke, A.M. & Dowling, K. (2017). Promoting social and emotional wellbeing in schools. Health Education, 117 (5), 434-451. doi: 10.1108/ HE-11-2016-0057

Bessell, S. (2009). Children’s participation in decision-making in the Philippines: Understanding the attitudes of policy-makers and service providers. Childhood: A Global Journal of Child Research, 16 (3), 299-316.

Biddle, N., & Swee, H. (2012). The relationship between wellbeing and Indigenous land, language and culture in Australia. Australian Geographer, 43(3), 215-232.

Boyatzis, C.J. (2009). ). Examining religious and spiritual development during childhood and adolescence. In M. De Souza, L.J. Francis & J. O’Higgins-Norman & D. Scott, International Handbook of Education for Spirituality, Care and Wellbeing, (pp.51-67). New York, NY: Springer.

Briggs, M. K., & Dixon-Rayle, A. (2005). Incorporating spirituality into core counselling courses: Ideas for classroom application. Counselling and Values, 50, 63-75.

Burckhardt, R. Manicavasagar, V., Batterham, P.J. & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of strong minds: A school-based mental health program combining acceptance and commitment therapy and positive psychology. Journal of School Psychology, 57, 41-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2016.05.008

Carlsson, D., Rowe, R. & Stewart, D. (2001). Health and wellbeing in the school community environment: Evidence for the effectiveness of a health promoting schools’ approach. Environmental Health ,1 (3), 40-50.

Carrington, C., Shepherd, J., Jianghong, L., & Zubrick, S. (2012). Social gradients in the health of indigenous Australians. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 107–117.

Carter, S. (2016). Holding it together: an explanatory framework for maintaining subjective well-being (SWB) in principals. [Thesis (PhD/Research)].

Carter, S. (2018). The Journey of a Novice Principal: Her struggle to maintain subjective wellbeing and be a spiritual school leader. International Journal of Education. (in Press).

Carter, S. & Creedon, M. (2019). Creating an inclusive school for refugees and students with English as a second language or dialect. In S. Carter (Ed), Opening Eyes onto Diversity and Inclusion. Toowoomba Australia, University of Southern Queensland.

Carter, S. & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education. doi 10.5772/66552

Cemalcilar, Z. (2010). Schools as socialization contexts: Understanding the impact of school climate factors on students’ sense of school belonging. Applied Psychology, 59 (2), 243-272.

Ciarrochi, J., Atkins, P.W.B., Hayes, L.L., Sahdra, B.K. & Parker, P. (2016). Contextual positive psychology: Policy recommendations for implementing positive psychology into schools. Frontiers in Psychology,7, 1-16. doi:/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01561

Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., Kashdan, T., Heaven, P., & Barkus, E. (2015). Hope and emotional well-being. A six-year longitudinal study to distinguish antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10, 520-532. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1015154

Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S.M. & Barnett, A.G. (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and wellbeing among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne. Social Science & Medicine, 71(8),1399-1408.

Curtis, R. C., & Glass, J. S. (2002). Spirituality and counselling class: A teaching model. Counselling and Values, 47, 10-13.

De Souza, M. (2009). Promoting wholeness and wellbeing in education: Exploring aspects of the spiritual dimension. In M. De Souza, L.J. Francis & J. O’Higgins-Norman & D. Scott, International Handbook of Education for Spirituality, Care and Wellbeing, (pp. 677-692). New York, NY: Springer.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. (2003). Personality, culture, and SWB: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review Psychology, 54, 403-425.

Dobmeier, R.A. & Reiner, S. M. (2012). Spirituality in the counsellor education curriculum: A national survey of student perceptions. Counselling and Values, 57 (1), 47-65.

Eckersley, R.M. (2007). Culture, spirituality, religion and health: Looking at the big picture. Medical Journal of Australia, 186 (10), S54-S56.

Fattore, T., Mason. J. & Watson , E. (2012). When children are asked about their well-being: Towards a framework for guiding policy. Child Indicators Research, 2 (1), 57-77. doi:10.1007/s12187-008-9025-3.

Fossey, W. (2017). Welcome to country [presentation]. Australia: University of Southern Queensland. Retrieved from https://player.vimeo.com/video/236851535

Fossey, W., Holborn, P., Abawi, L., & Cooper, M. (2017). Understanding Australian Aboriginal educational contexts. Australia: University of Southern Queensland. Retrieved from https://open.usq.edu.au/course/view.php?id=289

Fullan, M. (2010). All systems go: the change imperative for whole system reform. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B. L., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S. & Penn, D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden and build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 849-864. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002

Greensburg, M.T., Domitrovich, C.E., Weissberg, R.R. & Durlack, J.A. (2017). Social and emotional learning as a public health approach to education. Future of Children, 27 (1),13-32.

Grieves, V. (2006). Indigenous wellbeing: A framework for governments’ cultural heritage activities. Sydney, NSW: New South Wales Department of Environment and Conservation. Retrieved from http://www. environment.nsw.gov.au/conservation/IndigenousWellbeingFramework.htm

Grieves, V. G. (2008). Aboriginal Spirituality: A baseline for Indigenous knowldeges development in Australia. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 28(2), 363-398. Retrieved from http://www3.brandonu.ca/cjns/28.2/07Grieves.pdf

Hayes, L., & Ciarrochi, J. (2015). The thriving adolescent: Using acceptance and commitment therapy and positive psychology to help young people manage emotions, achieve goals, and build positive relationships. Oakland, CA: Context Press.

Heysen, C. & Mason, R. (2014). Bringing student voice to student wellbeing. Connect, 205 (Feb),15.

Holt, A. D., Smedegaard, S., Pawlowski, S.C., Skovgaard, T. & Christiansen, L. B. (2018). Pupils’ experiences of autonomy, competence and relatedness in move for wellbeing in schools: A physical activity intervention. European Physical Education Review, 20 (10), 1–19. doi:/10.1177/1356336X18758353

Jamal, F., Fletcher, A., Harden, A., Wells H., Thomas, J. & Bonell, C. (2013). The school environment and student health: A systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative research. BMC Public Health, 13 (798), 1-11.

Janssen, I. & LeBlanc, A.G. (2010). Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7(1), 40-40.

Kingsley, J., Townsend, M., Henderson-Wilson, C., & Bolam, B. (2013). Developing an exploratory framework linking Australian Aboriginal peoples’ connection to country and concepts of wellbeing. International journal of environmental research and public health, 10(2), 678-698. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/10/2/678/htm

Kashdan, T.B. (2010). Curious? Discover the missing ingredient to a fulfilling life. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishing.

Linkins, M., Niemiec, R.M., Gillham, J. & Mayerson, D. (2015). Through the lens of strength: A framework for educating the heart. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10 (1), 64-68. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.888581

Liu, M.L., Wu L. & Ming, Q.S. (2015). How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents? Evidence from a meta-analysis. PLOS, 1 (10).

McCallum, F. & Price, D. (2010). Well teachers, well students. Journal of Student Wellbeing, 4 (1), 19-34.

McCallum, F. & Price, D. (Eds.) (2016). Nurturing wellbeing development in education: From little things, big things grow. New York, N.Y: Routledge.

McCallum, F., Price, D. Graham, A. & Morrison A. (2017). Teacher wellbeing: A review of the literature. Retrieved from https://www.aisnsw.edu.au/…/Teacher%20wellbeing%20A%20review%20of%20the%…

McGrath, H. & Noble, T. (2012). Bounce back! A classroom resilience program: Teacher’s handbook. Sydney, NSW: Pearson Longman.

Naylor, P.J. & McKay, H.A. (2009). Prevention in the first place: Schools a setting for action on physical inactivity. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43 (1), 10-13.

Noble, T., McGrath, H., Wyatt, T., Carbines, R. & Robb, L. (2008). Scoping study into approaches to student well-being: Literature review. Report to the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Sydney, NSW: Australian Catholic University & Erebus International.

Panelli, R.; Tipa, G. (2009). Beyond foodscapes: Considering geographies of indigenous well-being. Health Place, 15, 455–465. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1353829208000944?via%3Dihub

Powell, M. A. & Graham, A. (2017). Wellbeing in schools: Examining the policy practice nexus. Australian Educational Research, 44, 213-231. doi: 10.1007/s13384-016-0222-7.

Price, D. & McCallum, F. (2015). Ecological influences on teachers’ well-being and ‘fitness’. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 43 (3), 195-209. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2014.932329.

Prout, S. (2012). Indigenous wellbeing frameworks in Australia and the quest for quantification. Social Indicators Research, 109(2), 317-336.

Queensland Studies Authority {QSA}, (2010). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander studies. Retrieved from https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/downloads/senior/snr_atsi_10_handbook.pdf

Quinlan, D., Swain, N., & Vella-Brodrick, D.V. (2012). Character strengths interventions: Building on what we know for improved outcomes. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13 (6), 1145-1163.

Reveley, J. (2013). Enhancing the educational subject: Cognitive capitalism, positive psychology and wellbeing training in schools. Policy Futures in Education, 11 (5), 538-548. doi:10.2304/pfie.2013.11.5.538.

Scoffham, S. & Barnes, J. (2011). Happiness matters: Towards pedagogy of happiness and Wellbeing. Curriculum Journal, 22 (4), 535-548.

Simmons, C., Graham, A. & Thomas, N. (2015). Imagining an ideal school for wellbeing: Locating student voice. Journal of Educational Change, 16 (2), 129-144.

Smith, B.H. (2013) School-based character education in the United States. Childhood Education, 89 (6), 350-355.doi:10.1080/00094056.2013.850921

Spears, B.A. (2016). Technology and wellbeing. In F. McCallum & D. Price (Eds.), Nurturing wellbeing development in education: From little things, big things grow (pp.2-20). New York, N.Y: Routledge.

University of Sydney, (2015). Kinship Module. Australia. Sydney, NSW: University of Sydney. Retrieved from http://sydney.edu.au/kinship-module/

Waters, L. (2011). A review of school-based positive psychology interventions. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 28 (2), 75-90.

Weare, K. & Nind, M. (2011). Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: Wht does the evidence say? Health Promotion International, 26 (S1), 129-169. doi:10.1093/heapro/dar075.

Yust, K.M., Johnson, A.N., Sasso, S.E. & Roehlkepartain, E.C. (2006). Traditional wisdom: Creating space for religious reflection on child and adolescent spirituality. In K. M. Yust, A.N. Johnson, S.E. Sasso, & E.C. Roehlkepartain, Nurturing child and adolescent spirituality: Perspectives from worlds religious traditions, (pp.1-14). New York, NY: Rowman Littlefield Publishers, Inc.