3 Policy, Frameworks and Legislation Informing a Focus on Wellbeing

Susan Carter and Andersen, Cecily

Key Concept

Policy, frameworks and legislation are complex and open to multiple interpretations which make enactment problematic.

Guiding questions

- Do policy, frameworks and legislation provide guidance?

- How is wellbeing enacted?

Introduction

National and state policy reports have indicated that many Australian students, teachers and leaders are experiencing difficulty maintaining their wellbeing. As educational contexts (e.g., schools, special education units and early childhood centres) represent a major component of Australia’s society and economy, it is no surprise then that national and international concern regarding the social and emotional wellbeing of children, young people and educators has now become a major focus in a wide range of international and Australian policy initiatives. As a consequence, interest has increased in the role educational contexts and educators play in promoting student wellbeing, and the interface that occurs between policy and practice when implementing wellbeing programs in schools. This Chapter explores Australian and international legislation, policy, and frameworks which inform a focus on wellbeing.

Activity

Before we examine policy, framework and legislation that informs a focus on wellbeing, how would you define each of the preceding terms?

Consider how the literature defines policy, framework and legislation, alongside the understandings you have of the concepts. Bacchi (2000) defined the term policy as a “discourse of ideas or plans that form the basis for making decisions to accomplish goals that are deemed worthwhile” (p.46). Cochran and Malone (2010) described policy in terms of the actions of government, and the intentions that determine those actions. Birkland (2016) espoused that the term policy referred to a plan of what to do, that has been agreed to officially, by either a group of people, an organisation or a government, in order to achieve a set of goals.

In contrast, the term framework has been conceptualised in a number of different ways. Coburn and Turner (2011) described a framework as an abstract, logical structure of meaning that guides action, and includes identification of key concepts, and the relationships between those concepts. On the other hand, Garrison (2011) considered a framework to be a set of beliefs, rules or ideas that outline what actions can be undertaken. White (2010) presented an alternate viewpoint, that a wellbeing framework is “a social process with material, relational, and subjective dimensions” (p.158), that can be assessed at individual and collective levels, with relationships at the centre. Compared to above, the term legislation is more simply defined as all Bill and Acts passed and subordinate legislation made by government.

Key Questions

Consider how wellbeing is represented in your own context’s policies and curriculum. How effectively is this applied?

Legislation informing a focus on wellbeing

McCallum and Price (2016) argue that at local, national and international levels, all children and young people have the right to an education that supports their wellbeing and development. As a consequence, improving the wellbeing and developmental outcomes of Australia’s children have become a key priority for Australian governments (Kyriacou, 2012). We will now explore legislation that impacts on the notion of wellbeing for children, young people and educational contexts (e.g., schools, special education units and early childhood centres).

Australian legislation

There are two key pieces of international legislation: Education and Child Protection Acts; and Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Act 1986.

Education and Child Protection Acts

The most significant pieces of guiding legislation for educational contexts across Australia are jurisdictional Education (General Provisions) Acts, which set out the conditions and requirements for the provision of education, and Child Protection Acts which set out protection for children and young people. However, while wellbeing is not referred to specifically in these acts, there is an underlying principle that guides both legislation and any subsequent policy on education, children and young people that falls out from legislation. The principle that governments must operate in “best interests of the child” is evident across all jurisdictions (Powell & Graham, 2017). (Your jurisdiction’s Education and Child Protection Acts can be located by searching for the relevant Act from your jurisdiction).

Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Act 1986

The Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Act 1986, overseen by the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission {HREOC}, plays a role in protecting and promoting the rights of children and young people within Australia. While the Act does not specifically promote wellbeing, it does refer to the right to an education and also provides policy and recourses to specifically to support the prevention of bullying, harassment and racism.

Activity

Consider how and why this legislation may or may not link to the definitions of wellbeing identified in Chapter 2.

International legislation

There are three key pieces of international legislation that have influenced the Australian landscape: the Convention on the Rights of the Child, United Kingdom Children’s Act 2004; and No Child Left Behind Act 2001.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child

The International Year of the Child (1979) brought commitment by national and international governments and organisations to extend human rights to children. As a consequence, the United Nations United General Assembly {UNGA} (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child {CRC} (1989) was developed. The CRC emphasized the civil and political rights of individual children as well as economic, social, and cultural rights; the right to be raised in peace; and the right to dignity, tolerance, freedom, equality and solidarity (UNGA, 1989). As Australia is a signatory to the CRC many of the principles within the Convention are embedded within legislation, policy and frameworks pertaining to children and young people.

United Kingdom Children’s Act 2004

The United Kingdom Government {UKG} Children’s Act 2004 was specifically designed to care and support children, with many of the principles from the Convention on the Rights of the Child embedded within this legislation. Part 2, Section 10 refers specifically to wellbeing and identifies six guiding principles: allow children to be healthy; allow children to remain safe in their environments; help children to enjoy life; assist children in their quest to succeed; to make a positive contribution to the lives of children; and to achieve economic stability for children’s futures (UKG, 2004).

No Child Left Behind Act 2001

In the United States of America {USA}, the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, 2001) focusses on the premise that setting high standards and establishing measurable goals can improve individual outcomes in education and the quality of lives of children and young people. While not specifying wellbeing development, the main goal of this Act is to close the achievement gap that separates disadvantaged children and young people and their peers. Waters (2017) argues that while closing the gap in educational attainment and opportunity may enhance wellbeing, much debate exists as to whether this Act contributes to or hinders the wellbeing of children and young people.

Activity

We suggest that you access both acts and consider the wording in each, and the implications of enactment.

- Compare and contrast the notion of wellbeing in the UKG Children’s Act 2004 and the USA No Child Left Behind 2001 legislation.

- Critique how wellbeing is defined or not defined within these documents.

- Critique the intentions of the above legislation.

Policy informing a focus on wellbeing

Powell and Graham (2017) note that the increasing focus on the social and emotional wellbeing of children and young people in Australia has attracted considerable community and political interest, with educational contexts now taking a key role in supporting and promoting the wellbeing of students. Waters (2017) argues that such interest has created a rapidly changing landscape of education governance within Australia, where responsibility shifts between state and Commonwealth governments, which in turn contributes to a broad and diffuse policy environment. The rising interest wellbeing has been guided by a number of key policy initiatives and approaches that have been put forward over the past decade.

Australian policy

There are two key pieces of influential Australian policy: the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians, and the National Mental Health Policy.

Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians

The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs {MCEETYA},2008) identified major world issues impacting on Australian schools including high levels of international mobility, ever-increasing globalisation and technological change, in conjunction with increased environmental, social and economic pressures and the ongoing acceleration of advances in information communication technologies, which together are placing greater demands on, and as well as providing greater opportunities for young people.

National Mental Health Policy

The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan (Council of Australian Governments Health Council {COAG}, 2017) outlines priorities to achieve the National Mental Health Policy {NMHP}. This plan also specifically outlines an agreed set of actions to address social and emotional wellbeing, mental illness and suicide as a priority, as well elevate the importance of addressing the needs of people who live with mental illness, and reducing the stigma and discrimination that accompanies mental illness.

For further detailed information, we suggest that you access both policies.

Activity

- Compare and contrast the notion of wellbeing in the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (2008) and the NMHP.

- Critique how wellbeing is implicitly or explicitly defined in each policy, and how well definitions align with notions of wellbeing discussed in Chapter 2.

- Critique the intentions of the documents, and how well they align with notions of wellbeing discussed in Chapter 2.

- Document and consider how elements of each policy could be in tension with each other, or with practice and programs in educational contexts .

International policy

There are two main pieces of international policy that have been influential in Australian landscape: Every Child Matters Policy United Kingdom; and the World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan for 2013-2020.

Every Child Matters Policy United Kingdom

Every Child Matters policy {ECM} (Government of the United Kingdom {GUK}, 2003) recognised 5 positive outcomes as being essential to children and young people’s wellbeing including: being healthy, happy and safe; developing skills for adulthood in order to get the most out of life; to make a positive contribution in life; being involved with the community and society and not engaging offending or anti-social behaviour and lastly experiencing economic wellbeing and full life potential.

It is worth noting that while there has been an increase in international wellbeing policy, there is still no universal definition or agreement as to what wellbeing is. Copestake’s (2008) study of international wellbeing policy identified contrasting views of wellbeing evident across many international policies. In many cases policies were based on very different contrasting assumptions about what the definition of wellbeing was, and how it could be achieved. Similarly, Spratt (2016) argued that within Scottish wellbeing policy “different professional discourses of wellbeing have migrated into education policy” (p. 223), which have resulted in differing views of wellbeing being represented.

World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan for 2013-2020

Student wellbeing has become a focus of international education policy for global organisations such as the World Health Organization {WHO}. The WHO identifies mental wellbeing as a fundamental component of good health and wellbeing. The WHO Mental Health Action Plan for 2013-2020 (WHO, 2013) is a comprehensive action plan that recognises the essential role of mental health in achieving health and wellbeing for all people.

Activity

- Examine the policies in your education system and compare and contrast the notion of wellbeing in each policy/ program / document.

- Critique how wellbeing is implicitly or explicitly defined in each policy, and how well definitions align with notions of wellbeing discussed in Chapter 2.

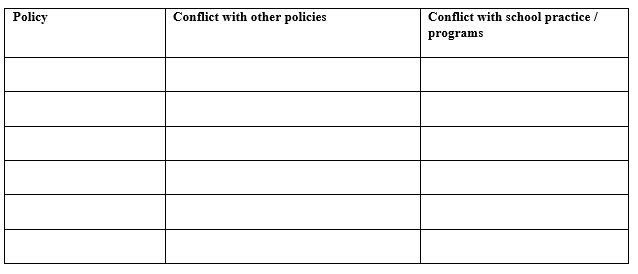

- Use the following template and consider elements of each policy that could be in tension with each other or with practice and programs in educational contexts.

Table 3.1 Elements of policy in tension

Frameworks informing a focus on wellbeing

Clarke, Sixsmith and Barry (2014) note that long-term benefits, such as improvement in social and emotional learning, increased social emotional functioning and improved academic performance are achieved for children and young people when wellbeing programs are implemented effectively. The following frameworks promote wellbeing as an intended key action.

Australian frameworks

Several Australian frameworks have promoted wellbeing as an intended outcome: National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009-2024; National Safe Schools Framework; Australian Student Wellbeing Framework; Learner Wellbeing Framework for Birth to Year 12; the National Framework for Values Education in Australian Schools 2005; the National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing.

National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009-2024

The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children {NFPAC}2009-2020 (Council of Australian Governments {COAG}, 2009) policy has a strong focus on protecting children and young people from abuse and neglect, with wellbeing highlighted as a key action.

The National Safe Schools Framework

The National Safe Schools Framework {NSSF} (Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs {MCEEDYA} (2011) provides Australian educational contexts with a set of guiding principles that assist school communities to develop positive and practical student safety and wellbeing policies (Australian Government Department of Education and Training {AGDET}, 2018). The NSSF is collaborative effort by the Commonwealth and State and Territory government and non-government educational context authorities and other key stakeholders. It places an emphasis on creating a safe and supportive educational context environment that promotes student wellbeing and effective learning, by addressing issues of bullying, violence, harassment, child abuse and neglect.

McCallum and Price (2016) also contended that the 2014 revision also provides Australian educational contexts with clear vision as well as a set of guiding principles that will enables educational contexts to develop contextually based positive and practical student safety and wellbeing policies, in addition to a number of practical tools and resources that will assist in the facilitation of positive school culture.The guiding profiles embedded within the NSSF forefront the valuing of diversity; the positive contribution of the whole educational community to the safety and wellbeing of themselves and others; the need to act independently, justly, cooperatively and responsibly in school, work, civic and family relationships; and the provision of appropriate strategies in order to create and maintain a safe and supportive learning environment (MCEEDYA, 2011).

Australian Student Wellbeing Framework

The Australian framework explores the role of educators, parents and students in promoting wellbeing and the online government site hosts a variety of resources to assist school communities. The vision outlined by the Ministers of Education Council {MEC} (2018) Australian Student Wellbeing Framework is for school learning communities to “promote student wellbeing, safety and positive relationships” so that students have the opportunity to reach their potential (MEC, 2018 p.1). In promoting student wellbeing the Australian government has put forward a framework that consist of five interconnected elements essential to the development, implementation and maintenance of positive learning environments and safety and wellbeing policies: leadership; inclusion; student voice; partnerships; and support provide the foundation for enhanced student wellbeing and learning outcomes:

- Leadership: Principals and school leaders play are an active role in constructing positive learning environments that are inclusive of the whole educational community, and where all educational community members feel included connected, safe and respected. Leadership needs to be visible and obvious to all members of the whole educational community.

- Inclusion: All members of an educational context’s community need to be included and connected to an educational context’s culture as well as being active participants in building a welcoming culture that values, diversity and promotes positive, respectful relationships.

- Student Voice: Students are key stakeholders within educational communities and as such are active participants in cultivating in their own learning and wellbeing, feeling connected and using their social and emotional skills to be respectful, resilient and safe.

- Partnerships: Support for student learning, safety and wellbeing requires effective school, family and community collaboration and partnerships.

- Support: Provision of wellbeing and support for positive behaviour for staff within an educational context, for students and for families by cultivating an understanding of wellbeing through the dissemination of information on wellbeing, cultivation a culture of wellbeing as well as support for positive behaviour and how this supports effective teaching and learning (Ministers of Education Council, 2018).

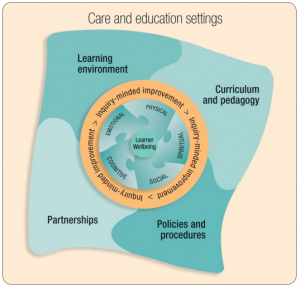

Learner Wellbeing Framework for Birth to Year 12

The former South Australian Department of Education and Children’s Services {SADECS} developed a Learner Wellbeing Framework {LWF} 2005-2010, that targeted all children and young people in South Australian educational sites and schools from birth to Year 12 (SADECS, 2007). Albrecht (2014) argues that as few learner wellbeing frameworks exist, this is a good example that can be applied national and internationally, as the LWF promotes wellbeing for all learners, by identifying wellbeing and learner engagement as key directions for educators. McCallum and Price (2016) also identified that the LWF acknowledges the interconnection between wellbeing and learning, and proposes that wellbeing is far more than the absence of problems. Powell and Graham (2017) likewise noted that the LWF acknowledges the complexity of the lives of contemporary learners and recognises the influences of change on today’s learners.

The LWF supports educators to build and improve effective wellbeing policies and practices, and is aligned to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC) (1989). The LWF supports educators to build and improve effective wellbeing policies and practices, and is aligned to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC) (1989).

The LWF (Figure 3.2) identifies five dimensions of wellbeing: the emotional dimension; the social dimension; the cognitive dimension; and the physical dimension; and the spiritual dimension, within four domains in an educational context: learning environment; curriculum and pedagogy; partnerships; and lastly policies (SADECS, 2007).

In considering the above frameworks, a major research study of wellbeing in Australian educational contexts conducted by Graham et al. (2014), identified that within Australian education systems, wellbeing is not clearly defined in policies, yet the term is frequently used in policy vocabularies. Graham et al. (2014) also established that there was little to no national nor state policy specifically targeting the wellbeing of children and young people, and that while many education websites signal an interest in wellbeing, very few provided specific detail other than identification of loosely related elements.

National Framework for Values Education in Australian Schools 2005

The National Framework for Values Education in Australian Schools (MCEETYA, 2005) is a framework and a set of principles for values education in twenty-first century Australian educational contexts. The framework recognises that there is a significant history of values education in Australian government and non-government educational contexts, which draw on a range of philosophies, beliefs and traditions. It also acknowledges that values education contributes to wellbeing development of children and young people. The framework identifies “guiding principles to support educational contexts in implementing values education; key elements and approaches to implementing values education; and a set of values for Australian schooling” (MCEETYA, 2005, p.1).

In responding to concerns around wellbeing, many educators have explored values-based frameworks. A case study by White and Waters (2015) identified that the use of a strengths-based approach framework contributed to the development of greater virtue, self-efficacy, and wellbeing in both children and young people.

National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing

The National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017-2023 (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council {AHMAC}, (2017) provides a dedicated focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, young people and adult’s social and emotional wellbeing and mental health. This framework endeavors to identify a culturally appropriate framework that guides and supports Indigenous mental health and wellbeing policy and practice.

There is an emerging global recognition of the significance Indigenous peoples’ wellbeing and the inadequacies of conventional socio-economic and demographic data that is used measure relative wellbeing. However, Prout (2012) argued that statistical data used to report on the wellbeing status of Indigenous populations is based on a preconceived set of assumptions grounded in the non-indigenous concepts of wellbeing, demography, and economic productivity and prosperity. Prout (2012) also argues that such assumptions directly impact on how Indigenous peoples are represented across broader society and to governments.

Key Question

Australian jurisdictional frameworks

Several Australian jurisdictions have been specifically developed wellbeing frameworks to promote and develop student and staff wellbeing in educational contexts and these include: Queensland Student Learning and Wellbeing Framework; New South Wales Wellbeing Framework for Schools; South Australian Wellbeing for Learning and Life Framework; and the Northern Territory Government Principal Wellbeing Framework.

Queensland Student Learning and Wellbeing Framework

The Queensland Department of Education, {QDE} (2018) Student Learning and Wellbeing Framework focusses on developing healthy, confident and resilient young people who can successfully navigate a more complex world. This framework combines a focus on learning and wellbeing. Key actions identified by the framework include: the creation of safe, supportive and inclusive environments; the building of staff, students and the school community capability; the implementation of supportive and inclusive environments; and the development of strong systems for early intervention(QDET, 2018).

New South Wales Wellbeing Framework for Schools

The New South Wales Department of Education and Communities {NSWDEC} (2015) Wellbeing Framework for Schools drives wellbeing development in educational contexts, by encouraging teaching and learning environments to focus on enabling the development of healthy, happy, successful and productive individuals. Within this framework students are also expected to contribute to their own wellbeing, the wellbeing of their peers and the collective wellbeing of their communities (NSW DEC, 2015).

South Australian Wellbeing for Learning and Life Framework

The South Australian Department of Education and Child Development {SADECD} (2016) Wellbeing for Learning and Life: A framework for building resilience and wellbeing in children and young people, applies across all areas of South Australian children and young people’s lives. This framework recognises the significant impact of education and care settings, and has links to the ACARA and the Early Years Learning Framework.

Northern Territory Government Principal Wellbeing Framework

The Northern Territory Government {NTG} (2017) Principal Wellbeing Framework specifically targets the wellbeing of school principals. This framework supports principal wellbeing by “empowering principals to build their own wellbeing capacity through increased knowledge, skills, resilience and resources” (NTG, p.3).

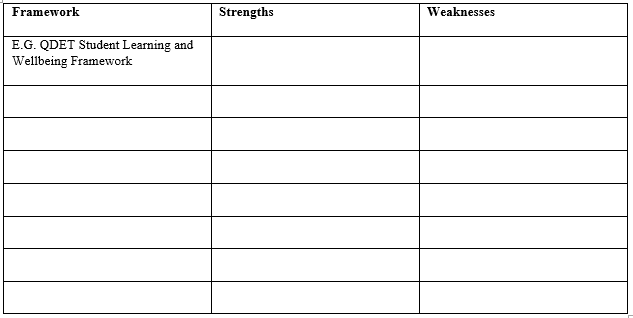

Activity

Use the following template to identify the strengths and weakness of each framework in addressing wellbeing within an educational context.

Other Influences

In Australia there have been several other influences on wellbeing and these include: Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, Australian Professional Standards for Principals; and the Australian Curriculum.

Australian Professional Standards for Teachers

The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers {APST} (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership {AITSL}, 2011) outlines a public statement of what constitutes teacher quality. Professional Standard 4, Create and Maintain Supportive and Safe Learning Environments provide a framework for fostering wellbeing and a mentally healthy educational community.

Australian Professional Standards for Principals

The Australian Professional Standards for Principals {APSP} (AITSL, 2014) provides a public statement setting out what school principals are expected to know, understand and do in order to succeed in school leadership. The accompanying Leadership Profiles arise directly from the Standards, and are presented as a set of leadership actions that effective principals implement in order to develop and support teaching that maximizes student learning.

Australian Curriculum

Powell and Graham (2017) note that governments across the globe are now using National Curriculum Frameworks as a means to implement student wellbeing. Waters (2017) also identified that Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s {OECD} (2015) Centre for Educational Research and Innovation’s {CERI} analysis of National Curriculum Frameworks across 37 OECD countries identified that student wellbeing was an explicit aim for 72% of countries, with many OECD countries are now aiming to systematically foster both academic outcomes and student wellbeing outcomes.

The Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority {ACARA}, 2016) sets out consistent national standards to improve learning outcomes for all young Australians. The General Capabilities of the Australian Curriculum specifically outline the need for students to develop social and emotional skills, and acknowledges the link between academic outcomes and mental health (ACARA, 2016). Developing personal and social competence and managing self, relationships, lives, work and learning more effectively; recognizing and regulating emotions and developing concern for, and understanding of others; establishing positive relationships; making responsible decisions; working effectively in teams; and handling challenging situations constructively are identified and key capabilities (ACARA, 2016). For further information we suggested accessing these frameworks in full.

Interestingly, the construct of wellbeing is not always viewed the same way in international educational judications. A study by Souter, O’Steen and Gilmore (2012) suggested that New Zealand educational system’s view of wellbeing differs from how it is conceptualized within literature, with words and phrases describing wellbeing constructs more often associated with the Relating domain rather than the Feeling domain. Thorburn’s (2017) examination of wellbeing in curriculum in Scotland identified a policy vision of a more progressive, integrated and holistic form of education; a commitment which contains an obligation for health and wellbeing to be a responsibility of all teachers, however, there were often issues with enactment of the policy due to problems communicating policy expectations.

In contrast, O’Toole (2017) outlines wellbeing as being conceptualised in Ireland in terms of child and youth mental health, and how that this informs a focus on school-based prevention and intervention approaches. And finally, Fattore, Mason and Watson (2012) propose a different perspective on wellbeing by exploring the use of student voice as mechanism for developing wellbeing in New Zealand’s curriculum frameworks.

Activity

- Critique how the notion of wellbeing as it presented in this group of frameworks.

- Critique how this group of frameworks align or do not align with previous frameworks.

- Consider elements of the APST, APSP and ACARA frameworks that could be in tension with each other or with practice and programs in educational contexts.

Conclusion

Chapter 3 has explored Australian and international legislation, policy, and frameworks which inform a focus on wellbeing. Investigation reveals that local, state, national and international jurisdictions all agree that children and young people have the right to an education that supports their wellbeing and development. Improving the wellbeing of Australian children and young people has also been a key priority for Australian governments. However, despite this there is no universal definition or agreement as to what wellbeing is and how it could be achieved, with many contrasting constructs of wellbeing evident across local, state and national Australian policies. The implementation of wellbeing policy, frameworks and legislation is then complex and open to multiple interpretations which make enactment problematic for educational contexts.

References

Albrecht, N. (2014). Wellness. The International Journal of Health, Wellness, and Society, 4 (1), 21-36.

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority {ACARA}. (2016). General capabilities. Retrieved from: http://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum/general_capabilities.html

Australian Government Department of Education and Training {AGDET}. (2018). National safe schools framework. Retrieved From https://www.education.gov.au/safe-schools-hub-0

Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council {AHMAC}. (2017). National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ mental health and social and emotional wellbeing. Retrieved from https://pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/mhsewb-framework_0.pdf

Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission {AHREOC}. (1986). Australian human rights and equal opportunity act 1986. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2017C00143

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership {AITSL}. (2011). Australian professional standards for teachers. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/apst-resources/australian_professional_standard_for_teachers_final.pdf

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership {AITSL} (2014). Australian professional standards for principals. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/australian-professional-standard-for-principals-and-the-leadership-profiles652c8891b1e86477b58fff00006709da.pdf?sfvrsn=11c4ec3c_2\

Bacchi, C. (2000) Policy as discourse: What does it mean? Where does it get us? Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 21 (1), 45-57. doi: 10.1080/01596300050005493.

Brikland, A. (2016). An introduction to policy process, theories, concepts and models of public policy making (4th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Clarke, A.M., Sixsmith, J. & Barry, M. M. (2014). Evaluating the implementation of an Emotional wellbeing program for primary school children using participatory approaches. Health Education Journal, 74(5), 578-593. doi: 10.1177/001789691455313.

Coburn, C.E. & Turner, E.O. (2011). Research on data use: A framework and analysis. Journal Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives, 9 (4), 173-206. doi.org/10.1080/15366367.2011.626729

Cochran, C.L. & Malone, E.F. (2010). Public policy: Perspectives and choices (4th ed.). Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Copestake, J. (2008). Wellbeing in international development: What’s new? Journal of International Development, 20, 577-597. doi: 10.1002/jid.1431

Council of Australian Governments {COAG}. (2009). Protecting children is everyone’s business: The national framework for protecting Australia’s children {NFPAC}2009-2020. Retrieved from https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/child_protection_framework.pdf

Council of Australian Governments Health Council {COAGHC}. (2017). The fifth national mental health and suicide prevention plan. Retrieved from http://apo.org.au/system/files/114356/apo-nid114356-451131.pdf

Fattore, T., Mason. J. & Watson, E. (2012). When children are asked about their well-being: Towards a framework for guiding policy. Child Indicators Research, 2 (1), 57–77. doi:10.1007/s12187-008-9025-3

Garrison, R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Graham, A., Fitzgerald, R., Powell, M.A., Thomas, N., Anderson, D.L., White, N.E. & Simmons, C.A. (2014). Wellbeing in schools: research project: improving approaches to wellbeing in schools: What role does recognition play? Lismore, NSW: Centre for Children and Young People, Southern Cross University.

Kyriacou, C. (2012). Children’s social and emotional wellbeing in schools: A critical perspective. British Journal of Educational Studies, 60 (4), 439-441. doi:10.1080/00071005.2012.742274

McCallum, F. & Price, D. (Eds.) (2016). Nurturing wellbeing development in education: From little things, big things grow. New York, N.Y: Routledge.

Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs {MCEECDYA}. (2005). National Framework for Values Education in Australian Schools. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/framework_pdf_version_for_the_web.pdf

Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs {MCEECDYA}. (2011). National Safe Schools Framework. Retrieved from https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/national_safe_schools_framework.pdf

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs {MCEETYA}. (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

Ministers of Education Council {MEC} (2018). Australian student wellbeing framework. Retrieved from https://www.studentwellbeinghub.edu.au/docs/default-source/aswf_booklet-pdf.pdf

New South Wales Department of Education and Communities {NSWDEC}. (2015). The wellbeing framework for schools. Retrieved from www.dec.nsw.gov.au.learning-wellbeing-framework.pdf

Northern Territory Government {NTG}. (2017). Principal wellbeing framework. Retrieved from http://teachintheterritory.nt.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/EDOC2017-66122-FINAL-DoE_PrincipalWellbeingFramework_web.pdf

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development {OECD}. (2015). Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills. OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/skills-for-social-progress-9789264226159-en.htm

O’Toole, C. (2017). Towards dynamic and interdisciplinary frameworks for school-based mental health promotion. Health Education, 117 (5), 452-468. doi: 10.1108/ HE-11-2016-0058

Powell, M. A. & Graham, A. (2017). Wellbeing in schools: Examining the policy practice nexus. Australian Educational Research, 44, 213–231. doi: 10.1007/s13384-016-0222-7

Prout, S. (2012). Indigenous wellbeing frameworks in Australia and the quest for quantification. Social Indicators Research, 109 (2), 317–336.

Queensland Department of Education {QDE}. (2018). Student learning and wellbeing framework. Retrieved from http://education.qld.gov.au/schools/healthy/docs/student-l

Spratt, J. (2016). Childhood wellbeing: what role for education? British Educational Research Journal, 42 (2), 223–239. doi: 10.1002/berj.3211.

South Australian Department of Education and Children’s Services {SADECS} (2007). Learner wellbeing framework. Retrieved from http://apo.org.au/system/files/29959/apo-nid29959-62641.pdf

South Australian Government Department of Education and Child Development {SADECS}. (2016). Wellbeing for learning and life: A framework for building resilience and wellbeing in children and young people. Retrieved from https://www.decd.sa.gov.au/sites/g/files/net691/f/wellbeing-for-learning-and-life-framework.pdf?v=1475123999

Soutter, A.K, O’Steen, B. & Gilmore, A. (2012) Wellbeing in the New Zealand curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44(1), 111-142. doi:10.1080/00220272.2011.620175.

Thorburn, M. (2017) Evaluating efforts to enhance health and wellbeing in Scottish secondary schools. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(5), 722-741. doi:10.1080/00220272.2016.1167246.

United Kingdom Government {UKG}. (2004). Children’s act 2004. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/31

United Nations General Assembly {UNGA}. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org.au/Upload/UNICEF/Media/Our%20work/childfriendlycrc.pdf

United States of America Department of Education {USADE}. (2001). No child left behind act. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/nclb/overview/intro/guide/guide.pdf

Waters, L. (2017). Visible Wellbeing in schools: The powerful role of instructional leadership. Australian Educational Leader, 39 (1), 6-10.

White, S.C. (2010). Analysing wellbeing: a framework for development practice. Development in Practice, 20 (2), 158-172. doi: 10.1080/09614520903564199.

White, M.A. & Waters, L.E. (2015). A case study of the good school: Examples of the use of Peterson’s strengths-based approach with students. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10 (1),69-76. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.920408.

World Health Organisation {WHO}. (2013). Mental health action plan for 2013-2020. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/89966/1/9789241506021_eng.pdf?ua=1