4 Contemporary Perspectives on the Impactors and Enablers to Wellbeing

Susan Carter and Andersen, Cecily

Key Concepts

- There are ways of working that impact and /or enable positive wellbeing.

- If ways of working are known to impact wellbeing then the impact or implications could be changed to achieve a more positive outcome.

- If ways of working are known to enable wellbeing then the impact or implications could be changed to achieve a more positive outcome.

Guiding question

- How is wellbeing enhanced?

Introduction

It is now widely accepted that wellbeing has moved to centre stage in recent years, with educational contexts now playing a vital role in prioritising the promotion of wellbeing of children and young people (MCEETYA, 2008). There is also growing international and national evidence that educational context-based wellbeing programs, when implemented effectively, produce long term benefits for children and young people, including improved social emotional functioning and academic performance (Clarke, Sixsmith & Barry, 2014). Additionally, McCallum and Price, (2016) argue that educational contexts also play a vital role in fostering teacher wellbeing. In order to understand the construct of wellbeing more, this chapter will explore contemporary perspectives on factors that impact on, and enable wellbeing, which have been termed impactors and enablers to wellbeing (Carter, 2016).

Perspectives on wellbeing impactors and enablers

There are differing perspectives on impactors and enablers of wellbeing. One study conducted in Queensland Australia by Carter (2016), acknowledged that impactors of Subjective Well-Being {SWB}were broadly what a participant reported as impacting upon their SWB. More specifically a negative impactor {referred to simply as impactor} was defined as that which detracts from a person’s SWB as a consequence of a negative evaluation. A positive impactor {referred to simply as an enabler} was defined as that which enhanced a person’s SWB as a consequence of a positive evaluation. Enablers were linked to a way of working intended to support the person to make a positive evaluation of their competency and therefore feel satisfied with life or feel positive affect.

Carter (2016) identified several major negative impactors to school principal’s SWB, such as a perceived lack of time to complete expected tasks; perceived lack of support; perceived lack of supervisor trust; self-doubting; inability to safe guard others; and questionable/poor decision making. Time was referred to with breadth as being time to learn; time to experience; insufficient time to think; and a preoccupation of thinking about work when in non-work related contexts. This impactor may well apply to teachers and students who report experiencing high levels of stress when faced with tasks they feel unable to complete competently within specified timeframes due to what Mulford (2003) terms as the busyness of educational contexts. A noted enabler was a feeling of control to create and maintain life balance and that this sense of balance {determined differently by each individual} helped them to maintain their positive SWB (Carter, 2016).

McCallum and Price (2016) suggest that wellbeing is more influenced by factors that impact on, and / or enable an individual to respond effectively in times of crisis, trauma, or ill-health. Approaches subscribing to this view tend to focus on resilience as a key impactor, and resilience development as a key enabler of wellbeing. While this perspective certainly has merit, there has been a growing movement, particularly in regard to the notion of wellbeing within educational contexts, that views wellbeing being as “more than just the absence of illness, and includes life satisfaction, healthy behaviours and resilience” (Ryff, 1989, as cited in McCallum & Price, 2012, p.4).

McCallum and Price (2016) suggest that there needs to be a positive and proactive approach to promoting wellbeing in educational settings, as it promotes wellbeing as a central focus and recognises the influences of change and the complexity in the 21st century, rather than being reactive and deficit in thinking. McCallum and Price (2016) likewise argue that this perspective also promotes a much more ‘holist’ view of wellbeing within a whole educational context. Additionally, Scoffham and Barnes (2011) argue that this approach also acknowledges the influence and interrelatedness between context, environment, life events, genetics and personality impactors and enablers on wellbeing such as:

- Context and physical environments: e.g., contextual processes and demographics, location, community and specific events such as drought, floods and cyclones;

- Social and cultural environments: e.g., culture, economics, politics and broader social issues such as poverty, community breakdown or violence;

- Individual personal attributes: e.g., genetics (heritage), psychological disposition and behavioural patterns (Litchfield, Cooper, Hancock & Watt, 2016).

Another perspective presented by Gillet-Swan and Sargeant (2015) is that the key components of wellbeing symbolise an intersection forming a triumvirate of the emotional, physical and cognitive self. As such, wellbeing ought be seen as the state of an individual as affected by these elements, within which, an array of descriptors exist.

Identifying impactors and enablers

Understanding the dynamic interplay and interrelatedness between factors that negatively impact wellbeing and factors that help support positive wellbeing can provide an insight into how they influence wellbeing (Gillett-Swan & Sargeant, 2015). Three broad themes have emerged from the literature: genetic factors; life circumstances; and involvement in active pursuits.

Genetic factors

Genetic factors such as an individual’s predisposition towards being happy or not, have the potential to either enable or impact on wellbeing. Although there are interactions between genetics, upbringing and environment, Diener and Oishi (2005) note that, genetic makeup acts as a strong precursor to wellbeing, where the temperament of the person has potential to act as a strong antecedent influence to wellbeing in either a positive or negative manner. Likewise, Burack, Blidner, Flores and Finch (2007) also argue that genetic factors account for “fifty percent of an individual’s predisposition to happiness” (Burack et al., 2007, p.3).

Life circumstances

Life circumstances and the impacts that life has had on an individual either enable or impact on wellbeing. Campion and Nurse (2007) note that life circumstances, such socio economic status, income, material possessions, marital status and community environment have potential to significantly impact and / or enable wellbeing. In contrast Burack et al. (2007) argue while life circumstances do impact on wellbeing, they can change very rapidly {either for the better or the worst}, and as such argue that they only account for “10 % of personal happiness variation even though society spends a disproportionate amount on them” (Campion & Nurse, 2007, p.27).

Involvement in active pursuits and special interests

Intentional involvement in active pursuits and special interests such as engaging in meaningful activities, participating in the workforce, socialising, physical activity and exercising and appreciating art, culture and life, can account for up to 40% of variation in happiness (Campion & Nurse, 2007), and as such have the greatest potential for influencing and enabling wellbeing. As a consequence, an individual’s chance of maintaining good wellbeing is increased by an active engagement in life. Conversely, non-participation has great potential to be a significant impactor on wellbeing.

Let’s now examine impactors and enablers through two models that place wellbeing as the central focus, the Dynamic Model for Wellbeing (Campion & Nurse, 2007), and the Positive Social Ecology Model (McCallum & Price, 2012).

Dynamic Model for Wellbeing

Campion and Nurse’s (2007) Dynamic Model for Wellbeing (refer to Figure 4.2) investigates the interaction between mental health and public health. The manner in which they outline wellbeing is similar to how other theorists have defined it with elements such as belonging, resilience, positive emotions meaning and fulfilment. This model has potential use and application in educational contexts as it illustrates the dynamic interplay between individual, physical and societal influences on wellbeing, through what are termed risk factors and protective factors. Campion and Nurse (2007) suggest:

- Reducing the impact factors on individual, and the individual in groups, whole context and within systems.

- Improving social and physical wellbeing.

- Creating supportive environments

- Improving protective factors such as employing therapists, accessing supports and empowering individuals.

This model places wellbeing at the centre of improving physical and social wellbeing, and recognises risk factors {impactors}, and protective factors {enablers} of wellbeing. While this model has broader application in terms of policy development, it does have application to an educational context, as it identifies three main impactors and enablers affecting an individual’s wellbeing: genetic factors; life circumstances; and involvement in active pursuits and special interests.

Activity

- Consider what elements of the above model may assist you in considering risk factors/ impactors and protective factors/enablers to wellbeing.

- If you used this model or aspects of it, what are the risk factors/ impactors or protective factor/enablers to wellbeing in your context?

Positive Social Ecology Model

McCallum and Price (2012)’s positive social ecology model draws on Bronfenbrenner’s (2004) work, and describes wellbeing within the natural, information, social and cultural environments of a community. This model identifies the following impacting and enabling factors:

- Intrapersonal factors: Interpersonal factors encompass the demographics of a group or community; the inter-relationships between people residing in that community; and the biological and psychological factors of the people within that community.

- Environmental factors: Environmental factors comprise the real or perceived views or experiences on crime, safety, physical attractiveness, comfort, convenience and accessibility and how they may impact on the immediate environment.

- Behavioural factors: Behavioural factors include the range of activities, services or access to programs, applications or structures available to people living and working in a community that enable them to be positively engaged as well as being intellectually, emotionally and physically active.

- Political factors: Political factors incorporate the policies, practices, infrastructure and communication that impact on people living and working within the community.

Activity

- Consider your own context for moment. Consider what elements of the above model may assist you in considering impactors and enablers to wellbeing.

- If you used this model or aspects of it, what are impactors or enablers to wellbeing in your context?

Impactors to wellbeing

McCallum and Price (2016) note that a range of factors that impact wellbeing on a daily, weekly or monthly basis {some of which are within one’s control and some which are not}, with some adversely affecting wellbeing. Impactors may also occur suddenly or accumulate over lengthy periods of time before physical and/or mental indicators become evident. Significant impactors include the following:

1.Personal responses to individual, physical, social or environmental impactors

Stress, fear, anxiety in response to stimuli such as peer conflict, relational conflict, harassment bullying, pressure from systemic requirements and time constraints, accountabilities, expectations and absence of a voice in decision making processes, can contribute to fatigue, exhaustion, stress, burnout, illness, and mental health issues which in turn may lead to poor overall wellbeing (Acton & Glasgow, 2015).

2. Unsuccessful adaptions to individual, physical, social or environmental impactors

Low levels of resilience, optimism, self-esteem, and feelings of having no control over one’s life, impact on an individual’s ability to respond effectively in times of crisis, trauma, or ill-health, and as such have major impacts on wellbeing.

3.Negative self-efficacy

Negative self-efficacy, self-judgment and self-belief impact on an individual’s view of their own self and their capabilities, which may lead to the development of negative self-view and poor wellbeing (Acton & Glasgow, 2015).

3.Negative or destructive relationships

Negative relationships between adults and adults, children and adults, and children and children arising from conflict, lack of emotional support, poor supportive environment, bullying, discrimination and harassment (Powell & Graham, 2017) impact greatly on wellbeing.

4.A lack of social-emotional competence/emotional intelligence

A lack of social and emotional competence or disposition impacts on wellbeing by cultivating negative or destructive relationships, which in turn contribute to a negative work, school or classroom climate, and subsequent loss of productivity (Abeles & Rubenstein, 2015).

Enablers to wellbeing

McCallum and Price (2016) identify three key enablers of a positive school ecology as hope, happiness and belonging that help enable wellbeing.

- Hope – Being optimistic about the future, pursing aspirations and taking control of one’s own wellbeing {being agentic} are key features in contemporary wellbeing education initiatives (Wrench, Hammond, McCallum & Price, 2013). The construct of ‘hope’ is comprised of two dimensions:

-

- The mental willpower to move towards achieving one’s goal {agency};

- The perceived ability to create pathways that enable the achievement of goals (McCallum & Price, 2016)

- Happiness – A positive emotional state.

- Belonging –Human beings have a fundamental need to belong and be accepted.

Activity

- Consider your own context for moment.

- Consider what elements of positive ecology exist in your setting.

Enablers to wellbeing in educational contexts

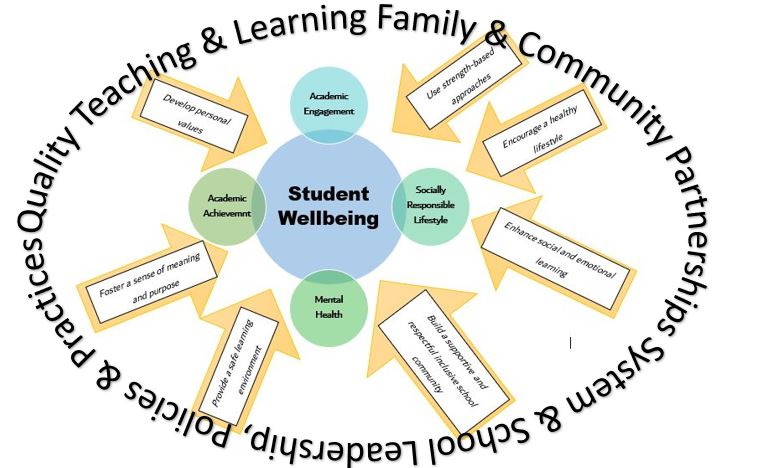

Noble, McGrath, Wyatt, Carbines and Robb (2008) in a report to the Australian Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations {DEEWR} identified the following seven enablers to wellbeing in educational contexts: (refer to Figure 4. 3):

- A supportive, caring and inclusive community

-

- Individuals feel welcomed, valued, respected and free form discrimination and harassment (Cahill & Freeman, 2007);

- Connectedness and opportunities to develop deep personal connections between individuals and groups (Acton & Glasgow, 2015);

- A sense of belonging;

- Feeling safe;

- Treated fairly;

- Positive peer and adult relationships where positive relationships have an affirmative influence on wellbeing, which in turn contributes to satisfaction, productivity and achievement (McCallum, Price, Graham & Morrison, 2017).

- Pro-social values

-

- The promotion of pro-social values including core values such were respect, trust, kindness, understanding, acceptance, honesty, compassion, acceptance of difference, fairness, responsibility care and inclusion (Noble et al., 2008).

- The presence of daily rituals that embed core values such as greetings, and visual images (McCallum & Price, 2016).

- Physical & emotional safety

-

- The presence of anti-bullying, anti-harassment and anti-violence strategies, policies, procedures and programs (Noble et al., 2008).

- Social & emotional competencies

-

- The presence of social and emotional coping skills, self-awareness, emotional regulation skills, empathy, goal achievement skills, relationship skills promote positive wellbeing (Noble et al., 2008). Social and emotional knowledge and dispositions are essential in order to operate and contribute productively (Mc McCallum & Price, 2016) in work, educational settings and the broader societal context.

- Effective emotional intelligence competencies enable wellbeing by facilitating the identification, processing, and regulation of emotion as well assisting in managing stress more effectively (McCallum, Price, Graham & Morrison, 2017).

- Resilience is essential to successfully adapt to and respond to complex or threatening life experiences and fast paced, challenging contemporary societal conditions. (McCallum, Price, Graham & Morrison, 2017).

- Positive self-efficacy is essential to producing positive productive performance. It also determines how an individual thinks, feels, and motivates themselves, thereby increasing potential for a positive state of wellbeing (Split, Koomen & Thijs, 2011).

- A strengths-based approach

-

- Having a focus on identifying and developing individual intellectual and character strengths promotes a positive state of wellbeing (Noble et al., 2008).

- A sense of meaning and purpose

-

- An intentional involvement in active pursuits and special interests such as “socialising and participating in {one or more} spirituality activities; community service; appreciating life, art/culture; and engaging in meaningful activities” (Campion & Nurse, 2007, p.25) are active enablers of wellbeing.

- Healthy lifestyle

-

- Engaging in exercise, having good nutrition and avoiding avoidance of harmful substances promote a state of positive wellbeing (McCallum, Price, Graham & Morrison, 2017).

Key Question

If you used this model or aspects of it, what are the possible impactors or enablers to wellbeing in your context?

Inclusion and Wellbeing

The models above all link in some way to a feeling of being included, with most linking to inclusion in educational contexts. As our world changes with increases in migration, refugee numbers and social complexity, our educational contexts also change and reflect what is happening within society (Abawi, Andersen & Rogers, 2019). What does this mean then for our educational contexts who are trying to engage in teaching and learning as their core business, in addition to being inclusive of a changing population?

Educational contexts often have families from many different countries and varying socio-economic backgrounds, all with differing experiences, beliefs, values, thinking and opinions. As a consequence, promoting and sustaining wellbeing within such contexts can at times be a very complex (yet essential) task. Educational communities need to be encouraged to embrace a shared philosophy of inclusion, and to participate in practices that are welcoming and supportive, encourage equity and view changes in student population and diversity as opportunities for learning (Carter & Abawi, 2018).

Carter and Abawi (2018, p. 2) suggest that “inclusion is defined as successfully meeting student learning needs regardless of culture, language, cognition, gender, gifts and talents, ability, or background.” A feeling of being included and belonging is associated with positive wellbeing, and creating an environment for this to occur involves catering for the needs of individuals. While the literature reveals that the term ‘special needs’ has been linked to both disability and disadvantage, Carter and Abawi (2018) suggest the term now be applied more broadly to include “the individual requirements of a person, and the provision for these specific differences can be considered as catering for special needs” (p. 2) and these needs include supporting wellbeing.

Conclusion

There are multiple ways of working within wider society, an organisation, and an educational context that can impact on and /or enable positive wellbeing. If particular ways of working are known to impact wellbeing, then it is suggested that the impact or implications be mitigated in order to achieve a more positive outcome. Likewise, if ways of working are known to enable wellbeing. then the impact or implications could be changed in order to achieve a more positive outcome. The Dynamic Model of Wellbeing (Campion & Nurse, 2007), the Positive Social Ecology Model (McCallum & Price, 2016) and the Revised Student Wellbeing Pathways (Noble et al., 2008) are suggested as possible models that could be utilised to investigate and analyse enablers and impactors within organisations and educational contexts.

References

Abawi, L., Andersen, C. & Rogers, C. (2019). Celebrating diversity: Focusing on inclusion. In S. Carter (Ed), Opening Eyes onto Diversity and Inclusion. Toowoomba Australia, University of Southern Queensland.

Abeles, V. & Rubenstein, G. (2015). Rescuing an overscheduled, over tested, underestimated generation. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Acton, R., & Glasgow, P. (2015). Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Teacher Education,40 (8),99-114.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2004). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on

human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Burack, J., Blidner, A., Flores, H. & Fitch, T. (2007). Constructions and deconstructions of risk, resilience and wellbeing: a model for understanding the development of Aboriginal adolescents. Australasian Psychiatry, 15, S18-S23.

Cahill, H & Freeman, E (2007) Creating school environments that promote social emotional wellbeing. In M. Keefe and S. Carrington (Eds.), Schools and diversity (2nd ed.). (pp. 90-107). French’s Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia.

Campion, J. & Nurse, J. (2007). A dynamic model for wellbeing. Australasian Psychiatry, 15, S24-S28.

Carter, S. (2016). Holding it together: an explanatory framework for maintaining subjective well-being (SWB) in principals. [Thesis (PhD/Research)].

Carter, S. & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education. doi 10.5772/66552.

Clarke, A.M., Sixsmith, J. & Barry, M.M. (2014). Evaluating the implementation of an emotional wellbeing programme for primary school children using participatory approaches. Health Education Journal, 74 (5), 578 – 593. doi: 10.1177/001789691455313.

Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2005). The non-obvious social psychology of happiness. Psychological Inquiry, 16 (4), 162–167.

Gillett-Swan, J.K. & Sargeant, J. (2015). Wellbeing as a process of accrual: Beyond subjectivity and beyond the moment. Social Indicators Research, 121 (1), 135-148. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0634-6.

Litchfield, P., Cooper, C., Hancock, C. & Watt, P. (2016).Work and wellbeing in the 21st Century. International Journal of Public Health, 13(11), 1065. doi:10.3390/ijerph13111065.

McCallum, F & Price, D (2012) Keeping teacher wellbeing on the agenda. Professional

Educator, 11(2),4–7.

McCallum, F. & Price, D. (Eds.) (2016). Nurturing wellbeing development in education: From

little things, big things grow. New York, N.Y: Routledge.

McCallum, F., Price, D. Graham, A. & Morrison A. (2017). Teacher wellbeing: A review of the

literature. Retrieved from https://www.aisnsw.edu.au/…/Teacher%20wellbeing%20A%20review%20of%20the%…

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA) (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

Mulford, B. (2003). School leaders: Changing roles and impact on teacher and school effectiveness. Education and Training Policy Division, OEDC.

Noble, T., McGrath, H., Wyatt, T., Carbines, R. and Robb, L. (2008). Scoping study into approaches to student well-being: Literature review. Report to the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Sydney, NSW: Australian Catholic University & Erebus International.

Powell, M. A. & Graham, A. (2017). Wellbeing in schools: Examining the policy practice nexus. Australian Educational Research, 44, 213–231. doi: 10.1007/s13384-016-0222-7.

Scoffham, S. & Barnes, J. (2011). Happiness matters: Towards pedagogy of happiness and Wellbeing. Curriculum Journal, 22 (4), 535-548.

Split, J.L., Koomen, H.M.Y, & Thijs, J.Y. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: The importance of teacher student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 457- 477. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y.

Wrench, A., Hammond, C., McCallum, F. & Price, D. (2013) Inspire to aspire: Raising aspirational outcomes through a student well-being curricular focus. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17 (9), pp. 932-947.