5.4 The social-emotional needs of the adolescent

The social-emotional needs of the adolescent are similar in many ways to the young child but with add-ins. For example, the adolescent has a strong focus on self and experiences the complications that come with hormones and puberty. Young people going through the stage of adolescence need to belong and feel connected, and they need emotional and social skills. Not all adolescents have had the chance to develop these skills so it should not be assumed that all adolescents have acquired these skills and indeed can competently demonstrate them. The adolescent as is the case with the younger child, does not have superpowers that allow them to become socially and emotionally competent through ‘magic’. All children who struggle with social-emotional competence need to be taught social and emotional skills.

Main and Whatman (2016) note that there is a “window of opportunity” (p. 1067) for the early adolescent who finds themselves embedded in a world of greater challenges both socially and academically. The authors remind us that the foundation of emotional stability is a strong relationship with a significant adult and having friendships with peers that are productive and respectful. Having a sense of belonging and connectedness significantly contributes to resilience and reduces the likelihood of disengaged and disruptive behaviours.

During adolescence concern with self-concept, self-esteem and appearance is greater than during the primary school years and can often lead to heightened anxiety and worry for some (Snowman et al., 2009). The inability to cope with these emotions can manifest into emotional disorders such as depression, eating disorders and substance abuse. This focus on self (self-conscious and self -centred behaviour) coupled with the flood of emotions that accompany the developmental changes of this adolescent stage, can create havoc for the social-emotional wellbeing of some adolescents. It is important to remember that while many adolescents do experience some social, emotional and behavioural hurdles, most of these hurdles fail to become significant difficulties.

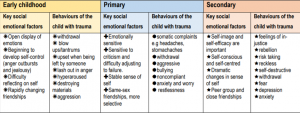

The following table is a compilation of key factors of social and emotional development developed from Snowman et al. (2009) and typical behaviours of the traumatised child of the same age from Wiebler (2013).

The secondary school space is full of transitions and changes. Transitions from room to room, teacher to teacher, subject to subject, physical changes from child to young adult, change for some from being known at primary school to being ‘lost’ amongst many. Changes everywhere. Changes that overwhelm. Keep the adolescent in mind.

Strategies to help

- Teach effective social communication skills for example: classroom positive graffiti walls (messages and art work); encouraging journal writing (no one reads it without owner permission); use alternatives to words (visuals, hand gestures, signs); model expression of emotion by reading an entry from your teacher journal (it is important that when students write in their journals the teacher does the same).

- We cannot change the past but with understanding, care and connection we can help to mend the fractures in the life of the child affected by trauma.Take advantage of the social opportunities in the school.

- Be a relationship coach. Be a role model in how to interact with others (Hertel & Johnson, 2013).

- Give feedback when social situations do not work out as planned.

- Ensure the peer group is included where appropriate so they too can be supportive and instrumental in helping.

- Establish a check-in time and place.

- Minimise the changes wherever possible.

References

Hertel, R., & Johnson, M. M. (2013). How the traumatic experiences of students manifest in school settings. In E. Rossen & R. Hull (Eds.), Supporting and educating traumatized students. A guide for school-based professionals (pp. 23-35). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Main, K., & Whatman, S. (2016). Building social and emotional efficacy to (re)engage young adolescents: capitalising on the ‘window of opportunity’. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(10), 1054-1069. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1145265.

Snowman, J., Dobozy, E., Scevak, J., Bryer, F., Bartlett, B., & Biehler, R. (2009). Psychology applied to teaching. Milton, Qld: John Wiley & Sons.

Wiebler, L. R. (2013). Developmental differences in response to trauma. In E. Rossen, & R. Hull (Eds.), Supporting and educating traumatized students. A guide for school-based professionals (pp. 37-47). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

.