2.4 Observing behaviour

Observing Behaviour = ABC

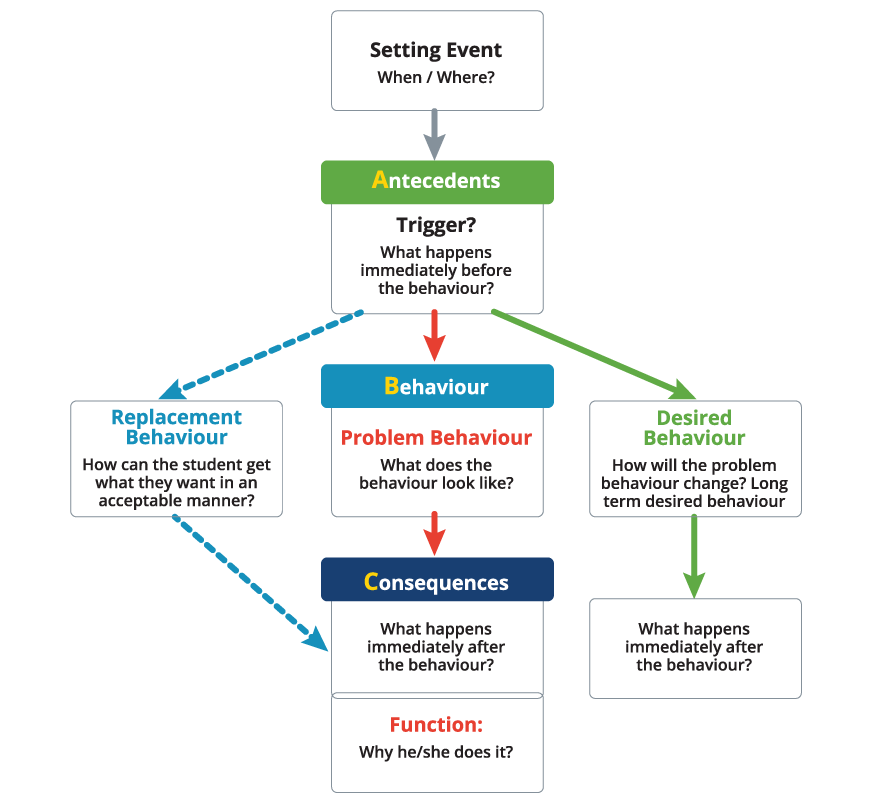

Thinking functionally about disruptive student behaviour assumes that behaviour is maintained by something in the environment where the behaviour is happening. To find out why or the function, we examine the antecedents, the behaviour and the consequences. That is, we watch or observe the behaviour directly and document the A, B and C of that disruptive behaviour.

Antecedent – what happens before the behaviour?

Behaviour – the actual behaviour that was observed

Consequence – what happens after the behaviour?

Even though the sequence says A, B then C – always start with the behaviour which is described in observable and measurable terms. If the behaviour is not described in a manner that tells others exactly what it looks like and sounds like, it is not only difficult to accurately observe and measure but determining the appropriate intervention, is made problematic. The behaviour is the actual behaviour that was demonstrated by the student. What does the behaviour look like in observable and measurable terms? Challenging behaviour needs to be explicitly described so that a visitor to the school would be able to accurately identify the behaviour. How we define behaviour guides how we measure it. Which of the following are observable and measurable?

| She knocks her book the floor and tells adults ‘No!” | He is anxious | She interrupts people when they are talking by constantly tapping them |

He leaves the room without permission |

| He pushes, punches and bites people |

She daydreams a lot | He hums and calls out swear words |

He lacks motivation |

| She is disrespectful |

She hits her peers | He has ADHD | She rocks on her chair, taps her feet |

The antecedent is what happened just before the behaviour did. It is sometimes called the fast trigger. While, the antecedent is often described as all the happenings within the context in which the behaviour occurs, it can be more helpful to think of the antecedent as what happens immediately before the behaviour. Other factors which also occur before the behaviour but over which the teacher often has little control, for example tiredness, hunger, fighting at home, removal from the family, are termed setting events. Awareness of these factors is important because while they are not an immediate trigger, they can significantly influence student behaviour. Some behaviourists choose to not single out the setting events from other antecedents (Umbreit, Ferro, Liaupsin, & Lane, 2007) but we will consider them separately and the antecedent recorded on the ABC form will be what happened immediately before the actual behaviour.

The consequence is what happens after the behaviour. What is it that the adults say or do? It is the consequence that will make the behaviour more or less likely to occur again. If the consequence encourages the behaviour to be repeated, it is called a reinforcer. If the consequence reduces the likelihood the behaviour will happen again, it is called a punisher. It is unfortunate that the term consequence is often used only in reference to punishment.

The table below shows the observable and measurable behaviours, highlighted in blue.

| She knocks her book the floor and tells adults ‘No!” | He is anxious | She interrupts people when they are talking by constantly tapping them | He leaves the room without permission |

| He pushes, punches and bites people |

She daydreams a lot | He hums and calls out swear words |

He lacks motivation |

| She is disrespectful |

She hits her peers | He has ADHD | She rocks on her chair, taps her feet |

Now that you understand the principles of a behaviourist approach and the importance of ABC for data collection, put on your trauma glasses and consider carefully the child affected by trauma. How can you apply this functional knowledge with thoughtfulness and caring consideration? You know that the child or young person is not “bad” or deliberately setting out to disrupt the learning and teaching and make your life difficult but is responding in a manner that reflects their current level of ability to cope. Their focus is on survival and they respond accordingly. They have no choice. It is up to the teacher to work out how best to guide and support the child whose trauma-driven behaviour is constantly sabotaging their ability to behave in a prosocial manner and successfully engage in learning.

Armed with knowledge about the impact of trauma on the brain, development, learning and behaviour, planning for the individual child demonstrating trauma-driven behaviour is a collaboration with many significant adults (e.g., family members, community workers, specialist personnel) to ensure all voices are heard and considered. Throughout the information and data collection process, the teacher, other educators and staff will come to know the child well. Taking a strengths-based approach underpins this work where the focus is on the capabilities, interests and unique strengths of the child. How to nurture a sense of safety and stability within the context of a trusting relationship, is the goal.

![]()

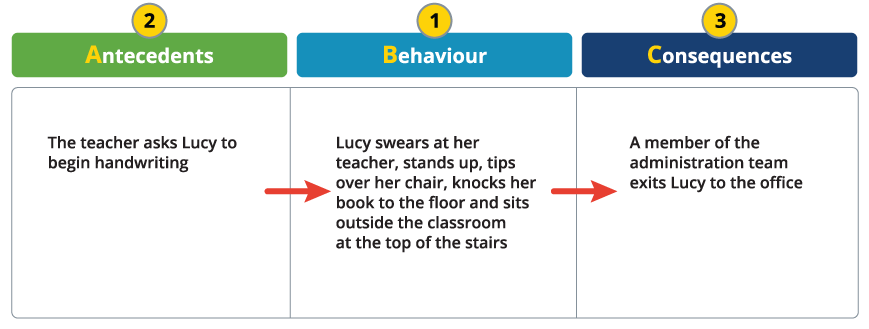

Identifying ABC

Read the following description and see if you can identify the antecedent, the behaviour and the consequence. Always start with the behaviour first, then the antecedent and then the consequence.

Lucy swears at her teacher, stands up, tips over her chair, knocks her book to the floor and sits outside the classroom at the top of the stairs whenever asked to begin handwriting. Lucy is escorted from the stairs to the office by a member of the administration team.

On a blank piece of paper rule three columns, one each for antecedents, behaviour and consequences. Take a moment to think of a disruptive student you have observed. Write down two of the disruptive behaviours demonstrated by the student in the behaviour column in observable and measurable terms. Now think back, what was the antecedent for each? Write those against each behaviour and what did the adults do after the behaviour happened? In other words, what were the consequences for each behaviour?

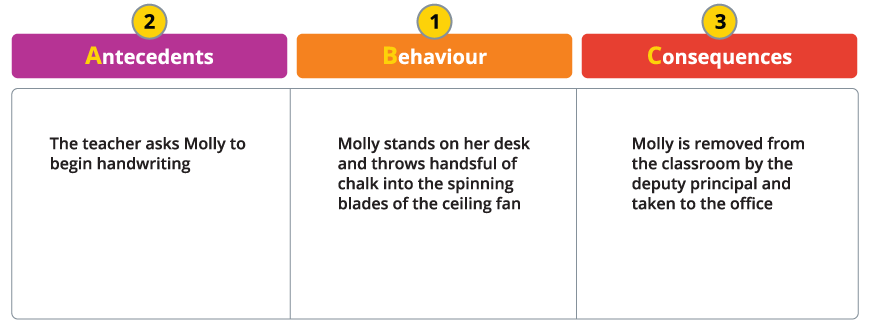

Your answer should look something like this:

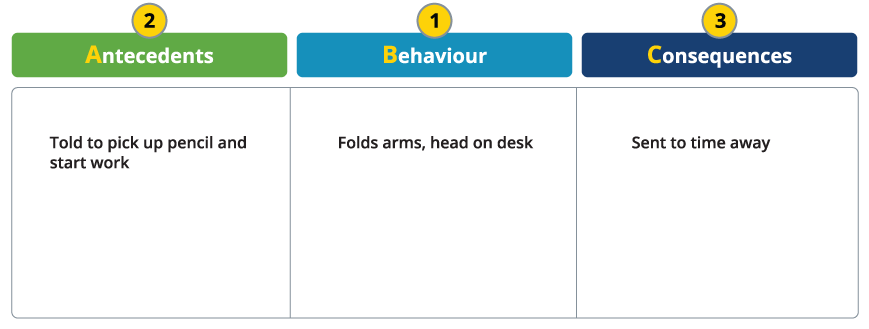

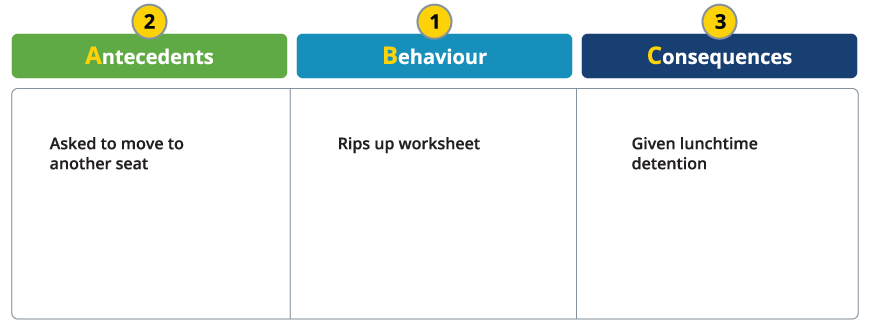

Here are two more examples of problematic behaviours with the antecedent and consequence. Make an effort to do your own.

![]()

Remember Molly?

Here is a reminder from the beginning of the chapter with greater detail:

The frantic phone call to the office came requesting immediate assistance in the Year one classroom. The teacher had instructed Molly to begin her handwriting task. Molly was holding the class to ransom (yet again) and the teacher was in the process of evacuation. Molly had taken the box of chalk from the shelf beneath the blackboard, had turned the ceiling fans up to the highest speed, climbed onto the desk and had begun to systematically throw handfuls of chalk into the spinning blades. Chalk ricocheted around the classroom like bullets from a machine gun and chaos reigned supreme. As a result, Molly is exited from the classroom by the deputy principal and taken to the office. This year, Molly’s disruptive behaviour had escalated to being serious and unsafe.

Draw up three boxes (see below) and write down the ABC of Molly’s behaviour. Start with the behaviour, then the antecedent and then the consequence.

Did you have what is in the example below or something similar?

What could the function of Molly’s behaviour be? Is it to access/get or avoid/get away?

Without data, it is impossible to know what the function of Molly’s disruptive behaviour is. After direct observations to collect ABC data and discussions with the teacher, it was concluded that the function of Molly’s behaviour was most likely to get adult attention and more specifically, get the attention of the deputy principal – and it worked! What better way to have the function met than to behave in an unsafe and dangerous fashion which automatically draws immediate attention from the school administration staff?

Data collection associated with functional thinking results in a hypothesis or behaviour statement which is our ‘best guess’ as to why the behaviour is happening. A behaviour support plan is then written and is the plan of intervention based on the data collected not based on hearsay and the ‘I reckon’ opinions of others. This behaviour support plan details the hypothesis statement (what the behaviour looks like and why we think it is happening), behaviour goals, academic goals and strategies to prevent the behaviour from occurring, to teach the replacement behaviours (the appropriate way for the child to get what they want – feeding the function) and to reinforce the appropriate behaviour.

At six years of age Molly had a very clear picture of the function of her behaviour and she articulated it clearly as illustrated in the example incident that follows. In response to the teacher’s call for help, the Deputy Principal had arrived at the classroom door and Molly seeing her there said: “I knew you would come. You have to come and get me if I am dangerous. It’s your job!” So where to now with intervention for Molly? The function of Molly’s behaviour needs to be fed. In other words, she has to be taught how to achieve the same function (to access adult attention) in an acceptable way. How could that be done? How could Molly access the attention she needs from the deputy principal in a manner that is appropriate and acceptable for the context and all people involved?

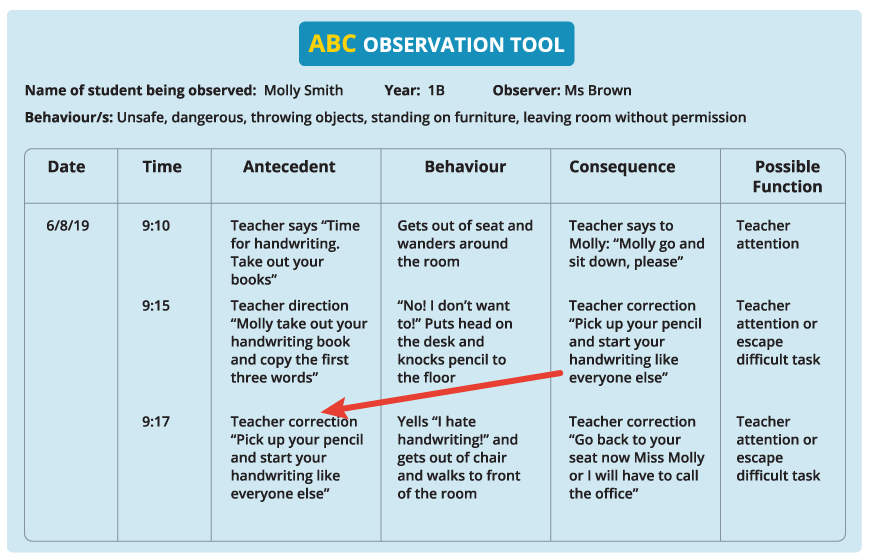

Here is a small part of a completed ABC example for Molly:

Follow the red arrow in this above example and notice how the consequence becomes the antecedent or trigger for the next behaviour. This is often (not always) the case. Completing an ABC requires that the disruptive behaviour is observed directly, that is that the observer (the teacher, teacher aide, behaviour support teacher or whomever) is watching the student demonstrate the disruptive behaviour within the environment that it is occurring. So, if the behaviour happens during Maths time in the classroom that is when and where the behaviour is observed.

Competing pathways

To this point you have closely observed and reflected on the relationship between the behaviour and the environment using the ABC. What happened immediately before the behaviour (the antecedent- A), the behaviour in observable and measurable terms (the behaviour – B) and carefully assessed what happened immediately after the behaviour by asking what did the adults do? (consequences – C). Remember, the reason the ABC was conducted was because the disruptive behaviour that was occurring needed to be changed because it was not acceptable. Changing behaviour requires a behaviour intervention plan or behaviour support plan that guides the implementation of the intervention strategies documented within it. The behaviour support plan is developed based on the competing pathway (three pathways). The ABC information or data is now used to fill out what is called the competing pathway which is a critical component of any behaviour support plan. A competing pathway looks like this (the questions are prompts for the information that is to go into each box). This helps us to focus our thinking, functionally.

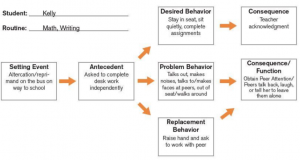

Here is a completed example from the literature, for student Kelly (Loman, Strickland-Cohen, Borgmeier, & Horner, 2010):

Note how the replacement behaviour allows Kelly to still achieve the same function. In this case this means an acceptable way for Kelly to access peer attention. So rather than use the problem behaviours of calling out, making noises, pulling faces etc. she is taught to raise her hand and ask permission to work with a peer. New replacement behaviour, same function. Unless the replacement behaviour serves the same function, the child will not use it because there is ‘nothing in it for them’. The disruptive behaviour gets them what they need so they will keep using it therefore the replacement behaviour must be worth their while and to be so, it must fill the same function for them as the disruptive behaviour does.

When deciding on a replacement behaviour we need to think about the following: What is it that (in the short-term) the child should be doing instead of the problem behaviour? What are all the other students doing that is appropriate to the task? What does the child need to do to access or escape and get what they need? We need to teach and reinforce it.

From competing pathways to support planning

With the competing pathway completed, now the behaviour support plan needs to be developed. The behaviour support plan will detail the strategies to prevent the problem behaviour, to teach the replacement behaviour and to reinforce the behaviours (replacement and desired behaviour). The plan also details how the adults involved need to respond. This is the way the behaviour support plan is usually set out with the strategies for each element of the competing pathway listed below each element.

This template is an easy to fill out behaviour support plan template. It clearly shows the alignment between the information in the A (antecedent), B (problem behaviour) and C (consequence) boxes and the intervention strategies corresponding to each. Antecedent strategies prevent, replacement behaviours are taught through the teach strategies and consequence strategies reinforce the replacement and desired behaviour.

Reflective questions

- Name three commonly held beliefs of causes of disruptive behaviour.

- Who is famous for operant conditioning?

- Behaviour is learned, lawful and _________________.

- Explain the importance of the ABCs of behaviour.

References

Loman, S., & Borgmeier, C. (2010). Practical functional behavioural assessment training manual for school-based personnel (p. 57) Retrieved from http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=sped_fac

Umbreit, J., Ferro, J., Liaupsin, C. J., & Lane, K. L. (2007). Functional behavioral assessment and function-based intervention. An effective, practical approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.