3.4 Effects of childhood trauma on academic achievement

The capacity of traumatised children and young people to learn is significantly compromised. Their neurobiology is stressed. Their relationships can feel unstable. Their emotional state is in flux. They find it difficult to stay calm or regain a state of calm if they feel distressed or perturbed. Change is perceived as dangerous. Their memory is under pressure. They are disconnected from themselves and time. Their behaviour rules them. New experiences and new information carry with them elements of threat and uncertainty.

Children and young people who have experienced toxic levels of stress and trauma find the demands of the school environment extremely challenging to navigate and benefit from. This is due to a range of factors. Firstly, toxic stress causes memory systems to degrade and fail. The more complex formed systems of memory are dissolved first. Without memory resources, learning is exceptionally difficult to consolidate.

Secondly, instead of following the natural rhythm which sees stress hormone level peaking in the morning and gradually wearing down during the afternoon and early evening, stress hormones in traumatised children can stay high constantly through the day. This contributes to limited attention span and difficulties with concentration. It also means that these children may experience eating and sleeping difficulties, which further impact on their capacity to engage positively with learning opportunities.

Thirdly, if trauma or stress occurs during the periods of time when the left hemisphere is more dominant in its maturation, then children and young people will experience difficulties with being able to process language, possibly leading to delays in language acquisition and comprehension. They are also more likely to experience difficulties with executing logic and sequencing tasks. They will therefore find maths and problem-solving tasks particularly testing. They will find narrative based techniques complex and at times indecipherable. At sport, they will struggle to read the play and flow of a game. They will need additional support to meet these challenges.

Finally, traumatised children and young people find the constant interaction with others at school a source of ongoing stress. School environments are semi-structured. They allow for change without the need for preparation. In these contexts, traumatised children and young people spend their energy just surviving. There is little room left for much else. Through adopting trauma informed approaches that are sensitive and predictable in their implementation, schools can open up a space for traumatised children and young people to learn.

Thinking functionally – regulation coping

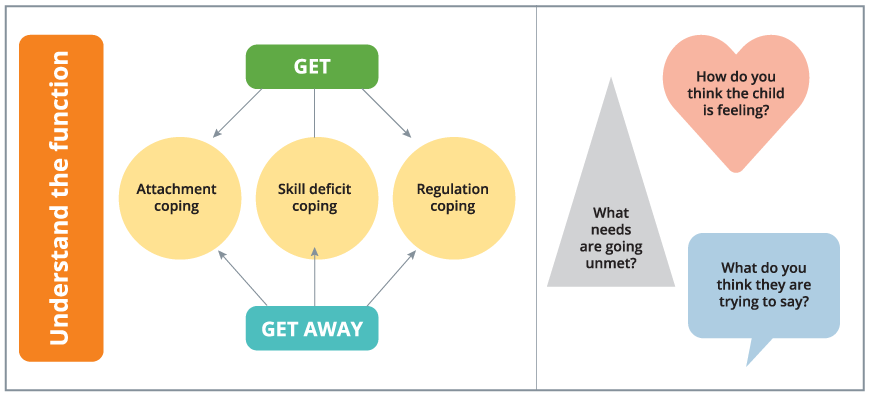

Children who are dysregulated and hyper-aroused cope by ‘getting’ access to sensorially soothing stimuli or objects or people who help them calm down. These children may also ‘get away from’ distressing sensory stimuli within the class (e.g., noise, sound, yelling voices) from people who maybe making them feel angry or anxious e.g., peers or adults or they may be trying to get away from school work that makes them feel anxious or bad about themselves because it is too hard.

Hypoaroused students- underaroused students may misbehave in an effort to cope by ‘getting’ access to sensory stimulating objects (e.g. prohibited items), experiences (e.g., running out of school) environments (shopping centre, oval) or people (e.g. antisocial peers). These students may also ‘get away from’ objects, experiences or people they find boring or underarousing e.g., boring school work, teachers, curricula activities they are not interested in.