1.3 Etiology of childhood adversity and maltreatment

Etiology or aetiology refers to a branch of knowledge concerned with causes – typically of social, psychological and medical phenomenon.

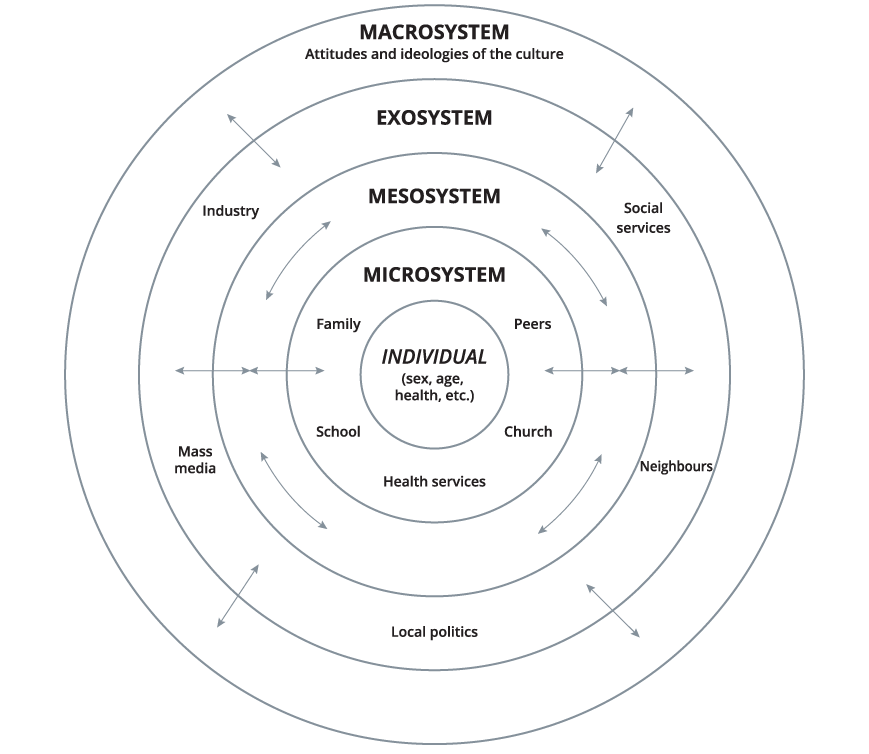

There is not any single fact which causes child abuse. Abuse usually occurs in families where there is a combination of risk factors. Any effort to identify definitive causes of child abuse and neglect is complicated by the interrelatedness of factors. One model that has been used to demonstrate how factors at multiple levels intersect to increase the likelihood of child abuse and neglect is Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ‘developmental-ecological’ model (Horton, 2003; Irenyi, Bromfield, Beyer, & Higgins, 2006).

The developmental-ecological model has four levels:

- cultural beliefs and values (macrosystem)

- neighbourhood and community settings (exosystem)

- family environment (microsystem)

- the individual’s own characteristics and developmental stage

International research has identified many risk factors for child abuse and neglect. It is beyond the scope of this book to provide detailed evidence of all of these risk factors or to discuss the extent to which specific risk factors relate to different forms of maltreatment. However, some of the commonly cited risk factors for child maltreatment, divided according to the ecological levels of the developmental-ecological model described above, especially relating to the macrosystem are not included as they are likely to vary significantly between societies and cultures.

Risk and protective factors can be used to develop both universal and targeted approaches to reducing child maltreatment. Universal approaches seek to reduce risk factors and promote protective factors in all families. This could include ensuring that all parents are provided with accessible information about parenting and child development. Identifying social and environmental risk factors such as low socio-economic status or neighbourhood disadvantage can inform systemic responses that seek to address the causes of disadvantage (Bromfield, Lamont, Parker, & Horsfall, 2010).

Identification of risk and protective factors can also be used to develop targeted approaches to reducing child abuse and neglect. Families that display multiple risk factors and minimal protective factors can be identified and provided with additional services and support (Putnam-Hornstein & Needell, 2011; Wu et al., 2004). Strengths-based practice, emphasising the assets and strengths within families, is a common strategy used to build and enhance protective factors and promote quality communication and engagement with families (Bromfield et al., 2012). All children and their families exhibit both risk and protective factors to some extent. The interaction of multiple risk factors in combination with limited protective factors may increase the likelihood of child abuse and neglect. Strong protective factors in families such as supportive social networks and a good parent-child attachment, and engagement with education can build resilience in children and parents.

RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS FOR CHILD MALTREATMENT

The presence of one or more risk factors, alongside a cluster of trauma indicators, may greatly increase the risk to the child’s wellbeing and should flag the need for further child and family assessment.

The following risk factors can impact on children and families and the care-giving environment:

Child and family risk factors include:

- family violence, current or past

- mental health issue or disorder, current or past (including self-harm and suicide attempts)

- alcohol/substance abuse, current or past, addictive behaviours

- disability or complex medical needs e.g., intellectual or physical disability, acquired brain injury

- newborn, prematurity, low birth weight, chemically dependent, fetal alcohol syndrome, feeding/sleeping/settling difficulties, prolonged and frequent crying

- parent, partner, close relative or sibling with a history of assault, prostitution or sexual offences

- experience of inter-generational abuse and trauma

- poverty, financial hardship, unemployment

- social isolation (family, extended family, community and cultural isolation)

- lack of stimulation and learning opportunities, disengagement from school, truanting

- inattention to developmental health needs and/or poor diet

- recent refugee experience

Parent risk factors include:

- parent/carer under 20 years or under 20 years at birth of first child

- lack of willingness or ability to prioritise child’s needs above own

- rejection or scapegoating of child

- harsh, inconsistent discipline, neglect or abuse

- inadequate supervision of child or emotional enmeshment

- single parenting or multiple partners

- inadequate antenatal care or alcohol/substance abuse during pregnancy

Wider factors that influence positive outcomes include:

- sense of belonging to home, family, community and a strong cultural identity

- pro-social peer group

- positive parental expectations, home learning environment and opportunities at major life transitions

- access to child and adult focused services e.g., health, mental health, maternal and child health, early intervention, disability, drug and alcohol, family support, family preservation, parenting education, recreational facilities and other child and family support and therapeutic services

- accessible and affordable child care and high-quality preschool programs

- inclusive community neighbourhoods

- service system’s understanding of neglect and abuse

PROTECTIVE FACTORS AND RESILIENCE IN THE SCHOOL CONTEXT

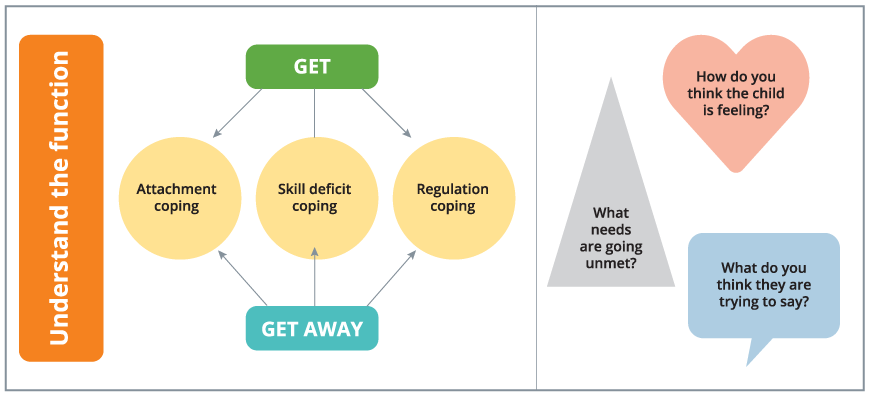

So how can we as educators support children with trauma in the school context and build their resilience with our knowledge of protective factors? Taking a strengths-based focus is paramount in helping the traumatised child. This means that we use the strengths and interests of the child to provide opportunities for experiences that promote success and a sense of accomplishment. Trauma informed practice can be viewed from both a deficit perspective and a strengths perspective. If we take a deficit view of the traumatised student our focus is on the difficulties, problems and challenges and the negative impacts on development for that student. If we take a strengths-based perspective we are focussed on the student’s abilities and how we can harness the positives to promote and guide the student with trauma towards successful experiences at school (Brunzell, Stokes, & Waters, 2016).

To do this we need to know what the student’s strengths, interests and abilities are. What are their interests? What do they like to do? Who are trusted people in the school? What are their academic strengths? How do we find this information out? Many teachers do this through planned instructional activities and also by seizing opportunities through teachable moments. Strategies may include: classroom games, talking to the previous teacher, talking to parents or significant adults in the student’s life or completing a short survey etc.

Remember that if the family environment (microsystem) of the child with trauma has been one where trauma has significantly impeded secure parental attachment, the development of the child is severely impacted. As Tobin (2016, p. 8) reminds “positive attachment to caregivers and adults acts as a protective factor to help develop self-regulatory capacities after trauma exposure”.

As teachers we should never underestimate the power of establishing strong connections and relationships. Brunzell et al. (2016, p. 67) suggests demonstrating “unconditional positive regard”. Ensuring that the classroom is a place where the student with trauma (and all students) feel a strong sense of belonging, value and safety while they are encouraged to take risks and learn. We have discussed some ideas here about protective factors and how these contribute to building resilience. It is ultimately about us providing an experience of safety and success. This is where the focus needs to be.

References

Bromfield, L., Lamont, A., Parker, R., & Horsfall, B. (2010). Issues for the safety and wellbeing of children in families with multiple and complex problems: The co-occurrence of domestic violence, parental substance misuse, and mental health problems (NCPC Issues Paper No. 33). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/issues33/>.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2016). Trauma-informed positive education: Using positive psychology to strengthen vulnerable students. Contemporary Psychology, 20, 63-83.doi: 10.1007/s40688-015-0070-x

Horton, C. (2003). Protective factors literature review: Early care and education programs and the prevention of child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Social Policy.

Irenyi, M., Bromfield, L. M., Beyer, L. R., & Higgins, D. J. (2006). Child maltreatment in organisations: Risk factors and strategies for prevention (Child Abuse Prevention Issues No. 25). Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/ issues25/issues25.html>.

Putnam-Hornstein, E., & Needell, B. (2011). Predictors of child protective service contact between birth and age five: An examination of California’s 2002 birth cohort. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(8), 1337–1344.

Tobin, M. (2016). Childhood trauma: Developmental pathways and implications for the classroom. Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). Retrieved from https://research.acer.edu.au/learning_processes/20

Wu, S. S., Ma, C. X., Carter, R. L., Ariet, M., Feaver, E., Resnick, M., & Roth, J. (2004). Risk factors for infant maltreatment: a population-based study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(12), 1253-1264.