16 Research ethics

Ethics is defined by Macquarie dictionary[1] as ‘the rules of conduct recognised in respect of a particular class of human actions’. Such rules are often defined at a disciplinary level though a professional code of conduct, and sometimes enforced by university committees called an institutional review board (IRB). However, scientists are also expected to abide by universal ethical standards of behaviour shared by the wider scientific community. For instance, scientists should not manipulate their data collection, analysis, and interpretation procedures in a way that contradicts the principles of science or the scientific method, or advances their personal agenda.

Why are research ethics important? Because, science has often been manipulated in unethical ways by people and organisations engaging in activities that are contrary to the norms of scientific conduct, in order to advance their private agenda. A classic example is pharmaceutical giant Merck’s drug trials of Vioxx, where the company hid the fatal side effects of the drug from the scientific community, resulting in the deaths of 3,468 Vioxx recipients, mostly from cardiac arrest. In 2010, the company agreed to a US$4.85 billion settlement and appointed two independent committees and a chief medical officer (CMO) to monitor the safety of its drug development process. In this instance, Merck’s conduct was unethical and in violation of the scientific principles of data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Ethics are only moral distinctions between right and wrong, so what is unethical may not necessarily be illegal. If a scientist’s conduct falls within the grey zone between ethics and law, they may not be culpable in the eyes of the law, but may still face severe damage to their professional reputation, lose their job on grounds of professional misconduct, and be ostracised by the scientific community. Since these ethical norms may vary from one society to another, here we refer to ethical standards as applied to scientific research in Western countries.

Ethical Principles in scientific research

Some of the expected tenets of ethical behaviour that are widely accepted within the scientific community are as follows:

Voluntary participation and harmlessness. Subjects in a research project must be aware that their participation in the study is voluntary, that they have the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time without any unfavourable consequences, and they will not be harmed as a result of their participation or non-participation in the project. One of the most flagrant violations of the voluntary participation principle is the forced medical experiments conducted by Nazi researchers on prisoners of war during World War II, as documented in the post-War Nuremberg Trials—these experiments also originated the term ‘crimes against humanity’. Lesser known violations include the Tuskegee syphilis experiments conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service from 1932–1972, in which nearly 400 impoverished African‑American men suffering from syphilis were denied penicillin even after it was accepted as an effective treatment for syphilis. Instead, subjects were presented with false treatments such as spinal taps. Even if subjects face no mortal threat, they should not be subjected to personal agony as a result of their participation. In 1971, psychologist Philip Zimbardo created the Stanford Prison Experiment, where Stanford students recruited as subjects were randomly assigned roles such as prisoners or guards. When it became evident that student prisoners were suffering psychological damage as a result of their mock incarceration, and student guards were exhibiting sadism that would later challenge their own self-image, the experiment was terminated.

If an instructor asks their students to fill out a questionnaire and informs them that their participation is voluntary, students should not fear that their non-participation may hurt their grade in class in any way. For instance, it in unethical to provide bonus points for participation and no bonus points for non-participation, because it places non-participants at a distinct disadvantage. To avoid such circumstances, the instructor could provide an alternate task for non-participants so that they can recoup the bonus points without participating in the research study, or by providing bonus points to everyone irrespective of their participation or non-participation. Furthermore, all participants must receive and sign an Informed Consent form that clearly describes their right to refuse participation, as well as their right to withdraw, before their responses in the study can be recorded. In a medical study, this form must also specify any possible risks to subjects from their participation. For subjects under the age of 18, this form must be signed by their parent or legal guardian. Researchers must retain these informed consent forms for a period of time (often three years) after the completion of the data collection process in order comply with the norms of scientific conduct in their discipline or workplace.

Anonymity and confidentiality. To protect subjects’ interests and future wellbeing, their identity must be protected in a scientific study. This is done using the dual principles of anonymity and confidentiality. Anonymity implies that the researcher or readers of the final research report or paper cannot identify a respondent by their response. An example of anonymity in scientific research is a postal survey in which no identification numbers are used to track who is responding to the survey and who is not. In studies of deviant or undesirable behaviours, such as drug use or illegal music downloading by students, truthful responses may not be obtained if subjects are not assured of anonymity. Further, anonymity assures that subjects are insulated from law enforcement or other authorities who may have an interest in identifying and tracking such subjects in the future.

In some research designs such as face-to-face interviews, anonymity is not possible. In other designs, such as a longitudinal field survey, anonymity is not desirable because it prevents the researcher from matching responses from the same subject at different points in time for longitudinal analysis. Under such circumstances, subjects should be guaranteed confidentiality, in which the researcher can identify a person’s responses, but promises not to divulge that person’s identify in any report, paper, or public forum. Confidentiality is a weaker form of protection than anonymity, because in most countries, researchers and their subjects do not enjoy the same professional confidential relationship privilege as is granted to lawyers and their clients. For instance, two years after the Exxon Valdez supertanker spilled ten million barrels of crude oil near the port of Valdez in Alaska, communities suffering economic and environmental damage commissioned a San Diego research firm to survey the affected households about increased psychological problems in their family. Because the cultural norms of many Native Americans made such public revelations particularly painful and difficult, respondents were assured their responses would be treated with confidentiality. However, when this evidence was presented in court, Exxon petitioned the court to subpoena the original survey questionnaires—with identifying information—in order to cross-examine respondents regarding answers they had given to interviewers under the protection of confidentiality, and their request was granted. Fortunately, the Exxon Valdez case was settled before the victims were forced to testify in open court, but the potential for similar violations of confidentiality still remains.

In another extreme case, Rik Scarce—a graduate student at Washington State University—was called before a grand jury to identify the animal rights activists he observed for his 1990 book, Eco‑warriors: Understanding the radical environmental movement.[2] In keeping with his ethical obligations as a member of the American Sociological Association, Scarce refused to answer grand jury questions, and was forced to spend 159 days at Spokane County Jail. To protect themselves from similar travails, researchers should remove any identifying information from documents and data files as soon as they are no longer necessary.

Disclosure. Usually, researchers are obliged to provide information about their study to potential subjects before data collection to help them decide whether or not they wish to participate. For instance, who is conducting the study, for what purpose, what outcomes are expected, and who will benefit from the results. However, in some cases, disclosing such information may potentially bias subjects’ responses. For instance, if the purpose of a study is to examine the extent to which subjects will abandon their own views to conform with ‘groupthink’, and they participate in an experiment where they listen to others’ opinions on a topic before voicing their own, then disclosing the study’s purpose before the experiment will likely sensitise subjects to the treatment. Under such circumstances, even if the study’s purpose cannot be revealed before the study, it should be revealed in a debriefing session immediately following the data collection process, with a list of potential risks or harm to participants during the experiment.

Analysis and reporting. Researchers also have ethical obligations to the scientific community on how data is analysed and reported in their study. Unexpected or negative findings should be disclosed in full, even if they cast some doubt on the research design or the findings. Similarly, many interesting relationships are discovered after a study is completed, by chance or data mining. It is unethical to present such findings as the product of deliberate design. In other words, hypotheses should not be designed in positivist research after the fact based on the results of data analysis, because the role of data in such research is to test hypotheses, and not build them. It is also unethical to ‘carve’ their data into different segments to prove or disprove their hypotheses of interest, or to generate multiple papers claiming different datasets. Misrepresenting questionable claims as valid based on partial, incomplete, or improper data analysis is also dishonest. Science progresses through openness and honesty, and researchers can best serve science and the scientific community by fully disclosing the problems with their research, so that they can save other researchers from similar problems.

Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs)

Researchers conducting studies involving human participants in Australia are required to apply for ethics approval from institutional review boards called Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs). HRECs review all research proposals involving human subjects to ensure they meet ethical standards and guidelines, including those laid out in the National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2007.[3] HREC approval processes generally require completing a structured application providing complete information about the proposed research project, the researchers (principal investigators), and details about how subjects’ rights will be protected. Data collection from subjects can only commence once the project has ethical clearance from the HREC.

Professional code of ethics

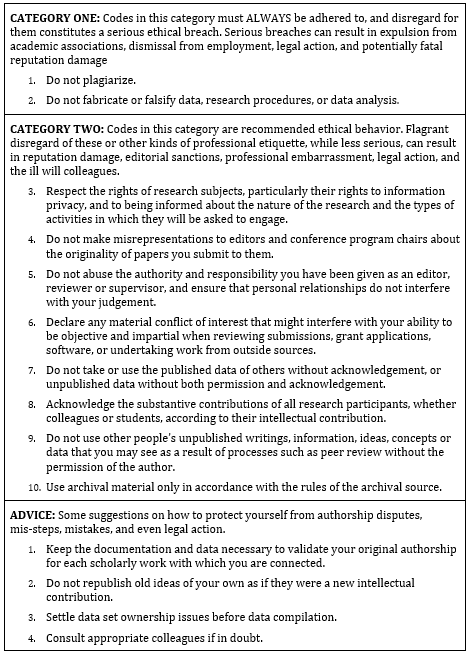

Most professional associations have established and published formal codes of conduct describing what constitutes acceptable professional behaviour for their members—for example the Association of Information Systems (AIS)’s Code of research conduct[4] which is summarised in Table 16.1.

The AIS Code of research conduct groups ethical violations into two categories:

Category I includes serious transgressions such as plagiarism and falsification of data, research procedures, or data analysis, which may lead to expulsion from the association, dismissal from employment, legal action, and fatal damage to professional reputation.

Category 2 includes less serious transgressions such as not respecting the rights of research subjects, misrepresenting the originality of research projects, and using data published by others without acknowledgement, which may lead to damage to professional reputation, sanctions from journals, and so forth.

The code also provides guidance on good research behaviours, what to do when ethical transgressions are detected (for both the transgressor and the victim), and the process to be followed by AIS in dealing with ethical violation cases. Though codes of ethics such as this have not completely eliminated unethical behaviour, they have certainly helped clarify the boundaries of ethical behaviour in the scientific community, and consequently, reduced instances of ethical transgressions.

An ethical controversy

Robert Allan ‘Laud’ Humphreys was an American sociologist and author, best known for his PhD thesis, Tearoom trade[5]— an ethnographic account of anonymous male homosexual encounters in public toilets in parks. Humphreys was intrigued by the fact that the majority of participants in ‘tearoom’ activities—also called ‘tea-rooming’ in American gay slang—were outwardly heterosexual men, who lived otherwise conventional family lives in their communities. Therefore, it was important to them to preserve their anonymity during tearoom visits.

Typically, tearoom encounters involved three people—the two males engaging in a sexual act and a lookout person called a ‘watchqueen’. Since homosexual sexual activity was criminalised in the United States at the time, the job of the watchqueen was to alert the men if police or other people were nearby, while deriving pleasure from watching the action as a voyeur. Because it was not otherwise possible to reach these subjects, Humphreys showed up at public toilets, masquerading as a watchqueen. As a participant-observer, Humphreys was able to conduct field observations for his thesis in the same way that he would in a study of political protests or any other sociological phenomenon.

Since participants were unwilling to disclose their identities or to be interviewed in the field, Humphreys wrote down their license plate numbers wherever possible, and tracked down their names and addresses using public databases. Then he visited these men at their homes, disguising himself to avoid recognition and announcing that he was conducting a survey, and collected personal data that was not otherwise available

Humphreys’ research generated considerable controversy within the scientific community. Many critics said that he should not have invaded others’ right to privacy in the name of science, while others were worried about his deceitful behaviour in leading participants to believe that he was only a watchqueen when he clearly had ulterior motives. Even those who deemed observing tearoom activity acceptable because the participants used public facilities thought the follow-up survey in participants’ homes was unethical, not only because it was conducted under false pretences, but because of the way Humphreys obtained their home addresses, and because he did not seek informed consent. A few researchers justified Humphrey’s approach, claiming that this was an important sociological phenomenon worth investigating, that there was no other way to collect this data, and that the deceit was harmless, since Humphreys did not disclose his subjects’ identities to anyone. This controversy was never resolved, and it is still hotly debated today in classes and forums on research ethics.

- Ethics. (n.d.). In Macquarie dictionary online. Retrieved from https://www-macquariedictionary-com-au.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/features/word/search/?word=ethics&search_word_type=Dictionary. ↵

- Scarce, R. (1990). Eco-warriors: Understanding the radical environmental movement. Chicago: The Noble Press, Inc. ↵

- Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council. (2018). National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2007. Retrieved from https://nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research ↵

- Association of Information Systems. (2014). Code of research conduct. Retrieved from https://aisnet.org/page/AdmBullCResearchCond ↵

- Humphreys, L. (1970). Tearoom trade: A study of homosexual encounters in public places. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co. ↵