8 Creating Sanctuary in Schools with Professor Sandra Bloom

For many of us advocating for trauma-informed practices, we may find ourselves isolated in schools that are stressed, under-resourced and punitive. In these systems, compassionate and thoughtful strategies to help students may face strong opposition and cynicism. What can be done to change such schools? We reached out to speak with psychiatrist Dr. Sandra Bloom. Dr. Bloom’s work on helping educational and health systems through trauma-informed leadership is ground-breaking and vital. Our discussion highlights critical issues facing our educational systems today and may shed light on ways to better care for our students and our teachers.

Dr. Sandra Bloom

Dr. Sandra Bloom is a psychiatrist and professor at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University in the United States of America. She is the president of Community Works, an organisational consulting firm committed to developing non-violent environments. Dr. Bloom is also the director of the Sanctuary program, an inpatient psychiatric program for treating trauma-related emotional disorders. Dr. Bloom’s first book, Creating Sanctuary, tells the story of understanding the connections between a wide variety of emotional disturbances and the legacy of child abuse and other forms of traumatic exposure. In more than 350 programs, considerable numbers of staff are now trained in Dr. Bloom’s Sanctuary Model, which is currently being used in various settings, including several schools.

Dr. Sandra Bloom is a psychiatrist and professor at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University in the United States of America. She is the president of Community Works, an organisational consulting firm committed to developing non-violent environments. Dr. Bloom is also the director of the Sanctuary program, an inpatient psychiatric program for treating trauma-related emotional disorders. Dr. Bloom’s first book, Creating Sanctuary, tells the story of understanding the connections between a wide variety of emotional disturbances and the legacy of child abuse and other forms of traumatic exposure. In more than 350 programs, considerable numbers of staff are now trained in Dr. Bloom’s Sanctuary Model, which is currently being used in various settings, including several schools.

Learn more about Dr. Bloom’s work by clicking or scanning the QR code.

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: How has your own experience of school influenced the work you do now?

Dr. Bloom: I went all the way through school at the same school district. It was called Lower Moreland – it’s in a suburb of Philadelphia in the United States. It was like growing up in a small town, in a small school. It was a very natural, democratic environment where teachers were interested in the kids. The kids came from middle-class families, mostly in brand new suburbs – post-World War 2. The social norm was that you helped others in the whole community and the school community. There were 100 kids in my graduating class, so it was small enough that everybody knew everybody. When a problem arose, it was noticed and addressed. Yet there weren’t many problems in those days. There was a stable economic situation for families. People had jobs. I was utterly unaware that violence existed. I did not learn about violence until I got out into the world. That was a real blessing that I didn’t think about such things until I saw the enormous contrast between other people growing up.

As an adult, I learned that Sociologists have come up with Dunbar’s number (see the box below for more information), which says that humans and our systems deteriorate after about 160 to 170 people. Since then, I have thought about all of the educational system’s problems, and we could probably solve all of them by just stopping to try and save money by getting bigger schools and instead returning to small schools where there are communities where children can learn how to be citizens. That has influenced a lot of my work in this field and continues to do so.

![]() Dunbar’s Number

Dunbar’s Number

Proposed by anthropologist Robin Dunbar (1992), ‘Dunbar’s number’ refers to a concept that limits the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships—relationships in which an individual knows who each person is and how each person relates to every other person. The proposed number is said to lie between 100 to 250 people and is commonly cited as 150 people (Dunbar, 1993).

Proposed by anthropologist Robin Dunbar (1992), ‘Dunbar’s number’ refers to a concept that limits the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships—relationships in which an individual knows who each person is and how each person relates to every other person. The proposed number is said to lie between 100 to 250 people and is commonly cited as 150 people (Dunbar, 1993).

Learn more by watching this TED talk [15:17 mins] by Robin Dunbar. Click or scan the QR code to start watching.

Defining Trauma

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: Given your expansive knowledge in this area, how do you explain what trauma is?

Dr. Bloom: When this field started, it was clear that trauma meant people had experienced a real threat to their life or witnessed a threat to life, or death and dying and other horrible things. That remains one of the definitions of trauma, but because we don’t have one word in English that embraces what we’re talking about, particularly to children, we use the word trauma as a shorthand to also represent chronic stress, toxic stress, relentless stress, and traumatic stress. With that caveat, I define trauma as “when the brain and body are overwhelmed, our physiology is overwhelmed by an experience that causes suffering.” In response to suffering, people often get derailed, their development gets derailed, the way they cope or try to cope derails them further, and we end up with complex problems. This suffering and attempt to cope isn’t necessarily directly due to the trauma itself, but due to the adaptations that children and adults make to deal with their disordered physiology and brain regulation.

![]() What is childhood trauma?

What is childhood trauma?

More than 20 years ago, Lenore Terr (1992) defined childhood trauma as the impact of external forces that “[render] the young person temporarily helpless and [break] past ordinary coping and defensive operation”. Terrasi and de Galarce (2017, p. 36) suggest that complex trauma is “the cumulative effect of traumatic experiences that are repeated or prolonged over time”.

More than 20 years ago, Lenore Terr (1992) defined childhood trauma as the impact of external forces that “[render] the young person temporarily helpless and [break] past ordinary coping and defensive operation”. Terrasi and de Galarce (2017, p. 36) suggest that complex trauma is “the cumulative effect of traumatic experiences that are repeated or prolonged over time”.

Learn more about trauma from our book Trauma Informed Behaviour Support by scanning the QR code.

Adopting a Public Health Approach

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: You mention that defining trauma has become increasingly complex. How do you see this complexity and resulting suffering in services and systems working with children?

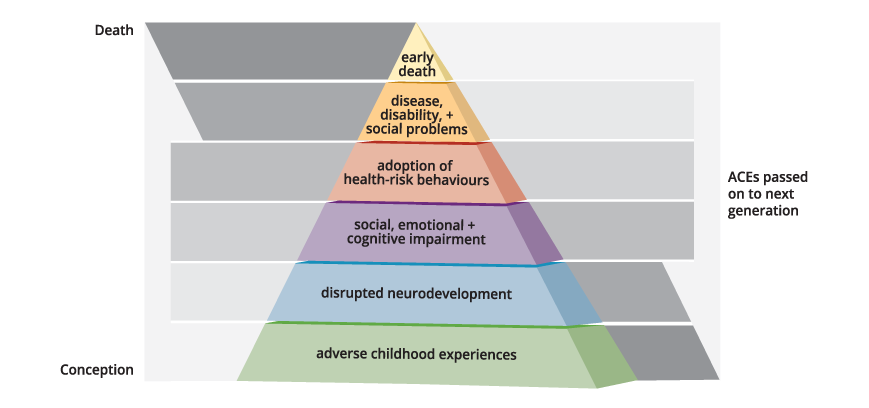

Dr. Bloom: We know from the Adverse Childhood Experiences study (ACEs study ; see the box below for more information) and all of the follow-up research that most of the population will experience a traumatic event in their lifetime. Most of the population have been, or will be, exposed to at least one ACE. A substantial minority have been, or will be, exposed to four or more ACEs. We have to address this. It’s a public health emergency that affects the whole community.

It can’t be a band-aid approach to meeting the needs of specialised, at-risk groups. These are community-wide concerns that have a multi-generational impact. This is why we need a public health approach to trauma. We must understand and spread knowledge about what we’ve learned so that everybody understands these concerns. Everyone in an organisation and community must understand the impact of trauma, from the staff, administrators, teachers, children, and their family members.

Let me give you an example of what I mean by a public health approach. A public health response is that we’ve made laws to ensure seat belts are in every car. Will everybody have a car accident? Thankfully no but will enough people be in danger and at high risk of having a car accident? Yes. So everybody has to wear seat belts. We need that kind of measure in place around the issue of trauma and adversity for the same reasons. Everybody’s at risk of experiencing trauma. Even if you’ve had a perfect childhood, you will interact with people who have had a difficult time growing up, and their distress will emotionally impact you. Being repeatedly confronted and affected by such pain and distress in others and within yourself may lead you to develop unhelpful coping skills. This is especially true in professions such as education. In this way, large groups of people may be impacted by the pain and distress of those in need.

This is why trauma-informed practices are critical for organisations and whole systems. We can’t pretend that this stuff isn’t real any longer. It’s very real, and anybody that works in any kind of workplace knows that, in the long-term, stress kills.

![]() Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Scan the QR code to watch this video from the movie ‘Resilience’ [4: 59 mins] from director James Redford – outlining the findings of the ACEs study.

Scan the QR code to watch this video from the movie ‘Resilience’ [4: 59 mins] from director James Redford – outlining the findings of the ACEs study.

The Sanctuary Model

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: Could you tell us about the Sanctuary Model and the model helps implement trauma-informed care in organisations and systems?

Dr. Bloom: The Sanctuary Model is an organisational approach that evolved from my original work running a psychiatric inpatient unit for adults and adolescents for over 30 years. We learned from our patients what it meant to help people who experienced trauma. We learned upfront, close and personal about the lived experience of these adults. Through caring for them, we learnt how to facilitate an environment that helped those experiencing distressing emotions related to a history of trauma and adversity.

We then applied those learnings and created a conceptual framework that we could teach other people. This framework centres on a set of values that are critical in creating a milieu or environment that keeps people safe. We use various tools to help people cope with the distressing emotions on a day-to-day basis.

Every school is a community, so schools are apt to have trauma-informed systems. Every school has a climate, every classroom has a climate, and there’s been a wealth of research about the importance of school climate for learning and classroom management.

The Sanctuary model is a newer articulation of longstanding ideas in healthcare and education that keep getting lost. It goes back hundreds and hundreds of years. We keep forgetting, and we have to rediscover it. Today we can integrate this knowledge through the emerging research on how trauma and adversity affect the brain and the body. So that’s what makes it so important and helpful for schools. You don’t have to think about this as ‘Oh, a brand-new flavour of the month.’ It’s well grounded in longstanding educational principles of how we must treat children to encourage learning.

It’s as simple as this: stressed kids can’t take in new information, and neither can stressed adults. It’s as simple as this: stressed kids can’t take in new information, and neither can stressed adults. This means that administrators have to take care of the staff, so that the staff can educate the kids. Suppose there’s lots of conflict among the staff or between the staff and administration. In that case, the teachers will be too stressed to pay attention to what the stressed children need to calm, regulate, and learn. This is all part of what we mean by trauma-informed education.

![]() The Sanctuary Model

The Sanctuary Model

The Sanctuary Model is a trauma-informed organisational change intervention developed by Sandra Bloom and colleagues. Based on the concept of therapeutic communities, the model is designed to facilitate the development of organisational cultures that support the victims of traumatic experience and extended exposure to adversity.

The Sanctuary Model is a trauma-informed organisational change intervention developed by Sandra Bloom and colleagues. Based on the concept of therapeutic communities, the model is designed to facilitate the development of organisational cultures that support the victims of traumatic experience and extended exposure to adversity.

Click or scan the QR code to read about the framework and its implementation [PDF].

Aligning Practice with Core Values

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: Why is it that we veer away from those core values? Does it have something to do with the experience of stress or our outlook on our work?

Dr. Bloom: I’ll start with the big picture. Our educational system has been afflicted by our unidimensional emphasis on money. If money and financial success are the only value, then it trumps everything else. And that’s what we’ve got happening here. Everything is sacrificed to the ‘God of money’. This has a corrupting influence on everybody. Even the most well-meaning people must try to align with what the next person in the hierarchy says about the factor that trumps everything else: “Yeah, that’s all good. That’s well-meaning. Yeah, it’d be nice if we could do that, but we can’t afford it.” It becomes difficult for people with a clear moral compass to challenge that moral infringement because they feel extraordinary levels of moral distress. Sometimes it’s so distressing that you start to ignore it completely. You get two selves, one responding to the power needs of those in control of the purse strings. The other self, more genuinely you, says, “I know this is wrong, but I’m too scared, I’m too intimidated, or I’m too threatened to be able to do anything about it.” I think that’s why articulating a value system consistently becomes so critical that it should be a primary leadership role.

Leaders should be speaking the values and walking the talk. What happens too often is that the value system gets put on the shelf, away from our daily decisions. Every single decision we make should include the test of whether it’s a good decision. Does this support or undermine the values that we say are important? If our purpose is to educate underprivileged children, who needs to learn things? We live in an increasingly inequitable society, what will we as adults do about that? How are we going to speak truth to power? How are we going to resist without becoming annihilated? It’s really about money, and it’s about power. It comes down to our education systems being in a moral crisis.

So, what can the individual do? Individuals alone are very vulnerable. We must figure out how to work together, collectively. In an individualistic culture, that’s a tough sell. But there is little hope unless we move in that direction. Schools are collective bodies. Schools can mobilise power within their community if they speak with one voice.

The S.E.L.F Framework

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: You have a lovely framework in the sanctuary program, the S.E.L.F framework. How can you use that to help children with their recovery from trauma?

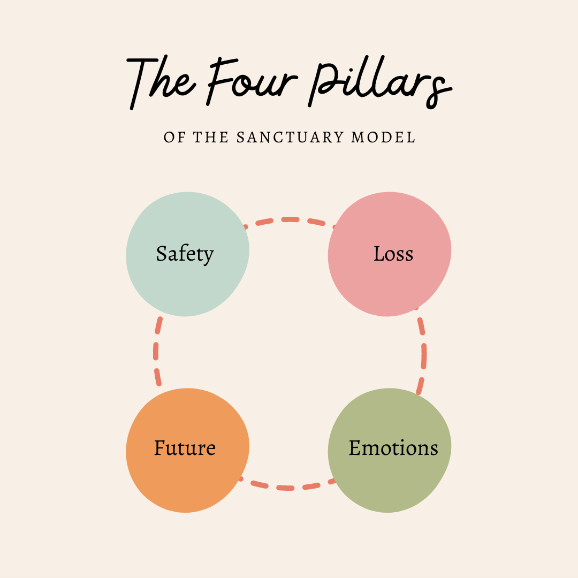

Dr. Bloom: S.E.L.F stands for Safety, Emotions, Loss, and Future. We think of it as a compass. It guides professionals to begin thinking about how to help another. For instance, a teacher is confronted by a distressed child who is chaotic and profoundly dysregulated. Where does the teacher start? You’re supposed to be educating this kid, and this child is too hyper-aroused to be able to teach them anything. They’re disrupting everybody else in the classroom. How do you even begin to think about where to start? And that’s where S.E.L.F comes in.

You start work with a child around identifying the safety issues. When we talk about safety, we talk about the four domains of safety, physical, psychological (within self), social (with others) and moral safety (safe within a system of values that are dear to you). You help a child think through all of their problems as safety issues. Underneath the S.E.L.F framework is a fundamental shift in mental models. S.E.L.F is saying, “This child in front of me, it isn’t a matter of whether they’re sick or bad, it’s that this is an injured child.” And we need a framework within which to think about an injured child. The first step is, how do I help you get safe in the world? That’s the S in S.E.L.F.

It would help if you took responsibility for you being safe, and I’ll help you as much as possible. We have to help you develop abilities to calm yourself down. You have to be safe with yourself, meaning you have to make the connection that what you’re doing is hurtful to you and your self-esteem. You have to be safer with other kids. You need to understand that when you get upset other kids catch it, and then the whole classroom gets out of control, and that’s not safe for me as your teacher.

The E is for emotions, recognising and regulating our emotions. We know that stressed people can’t manage their emotions very well, and emotions are critical for education. Emotions direct our attention to what’s important. A child dealing with violence cannot direct their attention to reading, writing, and arithmetic. It’s impossible; their brain doesn’t work that way. It’s part of our evolutionary heritage as humans. It becomes critical for teachers to develop skills to help children calm and become emotionally intelligent about their self-regulation. Children can then help each other in the classroom regulate their emotions. To do that, you must know what emotions you have the most problems regulating. To help a child recognise: “I’m okay until I pick up Johnny’s anger, and then I get scared, and when I’m afraid, I can’t think.” That is the conversation the teacher could have. Okay, what can you do? What can we help you figure out to do when you get afraid so that you can be less afraid?

Loss is the L which recognises that all change involves some loss. We don’t think about that much because we don’t like a loss. But people don’t resist change; we resist loss. Therefore, if you help a child to see that if you make a change, you will have to give up something, you are honouring that child’s loss. If you’re going to use exercise to help yourself calm down, it’s going to take time, and you’ll have to give up time playing your video games. Are you willing to make that commitment to improve your emotion management skills? In this sense, all change requires loss for kids and adults. We then ask, why should we change? Well, because we envision a future, that’s where the F comes in.

We want something and will have to give up something in return. So we have to have a clear vision of what we want. When you’re challenging a child to make a change and manage their emotions to get safe, no human being will do that unless they have a vision of why. What would that feel like? What will it feel like for a student to not to have me discipline them all the time? Can they imagine taking a math test and getting an A plus? Can they imagine that happening even though they failed every math test this semester?

You may start with a teacher using S.E.L.F and you can start anywhere in the framework. It might start with asking where are we trying to get to? You may say “I need to talk with you, Johnny, because this is what I see happening, and I’m worried about you. But let’s start with the idea that everything works, everything you and I are going to plan, it works, and you are successful. What does that look like to you? Give me an example of something you’ve been successful at before. Now you can imagine the future goal, and then we’ll link the goal back to where we are now”. This organises the chaos in the teacher-student relationship.

When using the S.E.L.F framework, many people miss the L – the loss. We don’t calculate what the person will have to give up. That’s important to consider with traumatised people. Whats at stake if they stop using the unhealthy habits they’ve used to cope? They have to sit with unimaginably terrible feelings, and we’re not good at understanding that. We need empathy for their experiences and emotions to help them figure out what to do and learn to improve it. In this way, S.E.L.F is a powerful and straightforward tool, yet simultaneously complex.

![]() The S.E.L.F Framework

The S.E.L.F Framework

S.E.L.F. is a problem-solving framework that represents the four dynamic areas of focus for trauma recovery. It offers a trauma-informed way of organising conversations and documentation for clients, families, staff, and administrators by moving away from jargon and towards more simple and accessible language.

S.E.L.F. is a problem-solving framework that represents the four dynamic areas of focus for trauma recovery. It offers a trauma-informed way of organising conversations and documentation for clients, families, staff, and administrators by moving away from jargon and towards more simple and accessible language.

Click or scan the QR code to learn more from this resource from the Mackillop Institute.

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: I like how you frame unsafe or oppositional behaviour as a coping strategy for those who are traumatised. Could you say more about this?

Dr. Bloom: We learned this from our patients, many of whom were self-mutilating or self-harming. We tried all kinds of punitive strategies to get them to stop self-harming. Of course, it was a complete failure. Until we understood that the cutting was how they were coping with feelings that felt worse. We couldn’t expect them to give up an effective coping skill unless we could replace it with something healthier and just as effective. That’s how we learned to approach these kinds of problems entirely differently.

Oprah talked about this last year on a TV program she had. She said, “This revolutionary approach, it’s not ‘what’s wrong with you?’. We’ve stopped asking that question. Now we ask the question, ‘what happened to you?’. It was my friend Joe Foderaro, a social worker in 1991, who said that in a team meeting. When you see that problem behaviour, you must start with: I wonder what that’s about? Why would somebody react that way? What happened that could produce that outcome or behaviour? How can we figure out how to redirect that behaviour into more positive, self-affirming, creative, and educational channels? Unless you get that original shift, you don’t get anywhere. You just end up trying to punish people who are already profoundly punished for doing their best at coping.

Systems Under Pressure

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: We often hear from many teachers who don’t feel supported by their leaders and colleagues to work in a trauma-informed manner. What early warning signs can people pick up on when an organisation or a system is under stress and perhaps not functioning the way it should be?

Dr. Bloom: The only antidote that we have to the effects of trauma is social support. For example, if you go into a staff room in a school, and there’s a lot of hostility and tension, we pick that up instantaneously. Those are signals of danger. There’s likely little social support in that environment. Other indicators of systems under stress include chronic conflicts that are not resolved; there are no conflict management strategies routinely in place; a lack of training on the impact of stress and trauma on the teachers, students or their families; a punitive environment where the reaction to the breaking of rules or episodes of violence is to punish students or adults. If you’re interviewing for a job, and pick up on these signs, don’t go there.

There are also authoritarian leadership principles. Authoritarianism is a disaster for human groups unless they are in an acute crisis. In an acute crisis, it’s a good strategy to use. After that, the only thing that is going to be effective is democratic processes. Other warning signs include a lot of secrecy, which often indicates communication problems exist within the system; how many violent incidents have there been? And how many times are students pushed out of the classroom and punished for their problems? Has that been rising or decreasing? Is it being addressed, and how? How are behaviour problems at the school addressed? What are the expectations of teachers? Is there any support for teachers? What happens if you’re having a difficult time with a child? Are there people in the school who are called in when there’s any kind of emergency, not just as police, but as real helpers? Is there attention being paid to the students and teachers?

These are things you see in an environment that’s becoming increasingly sick. Remember that organisations are like organisms. They are living, adaptive, complex systems. It becomes a worry when everybody’s reaction to a stressful situation is to try to make a new rule, and the accumulation of rules is a very clear indicator that social norms are eroding. Pay attention to the social norms of the system. Positive social norms will include bringing people within the system together, talking about the rising level of incidents, and talking about what’s going on with our group and what’s going on collectively.

It’s not just seeking out a new rule or a new person to punish to ‘fix’ the system, it will never work. But that’s what we do over and over again, and I’ve seen that happen in all kinds of organisations, and I’ve definitely seen that happen a lot in schools where the attitude is, these kids are out of control, so we need more punishment, and they need more consequences.

It’s always called consequences, and there are always consequences for everything that we do. You want the consequences to be deliberately designed for that group or that student that’s going to get you more of what you want that student to be. If you apply the same consequences to everybody, it makes no sense. It makes the system incredibly stupid because one student will be breaking a rule because they’re pushing the limits of authority to see what they can get away with and find where the limit is. Yet another student will be breaking the rule because it’s a coping skill that they’ve learnt to deal with terrible stuff that’s going on at home. Now, if you consequence those two students, in the same way, you’ve totally missed the point.

It’s really important that people who run organisations are able to identify when their systems are getting sick. Just like we identify the signs of the flu or a cold within ourselves, we go in for a check-up to help us recover and heal our bodies. Systems are living bodies, they can get well and heal and recover from stress, but not if you ignore the symptoms. You’re describing that the system had adapted to a sick way of functioning. That’s what whole communities do, and that’s what entire societies do. We adapt to sick, inhumane conditions and then wonder why things are so messed up. Well, they’re sick, ill, and dysfunctional, and it’s time that we were willing to stake our claim around knowing what health an organisation is in. How does a healthy organisation function? What is a healthy school? Let’s get out there and say it. Those of us who have been in lots of systems, get us all together, and we’ll have no trouble talking about and voicing it. But it’s not talked about, and we don’t think about it. We do this when we as individual human beings are sick. We know how bad it feels to feel sick, and we know what it feels like to feel well. We need to be doing that at an organisational level too.

![]() Trauma-informed Organisational Change and Support

Trauma-informed Organisational Change and Support

Crisis-driven organisations sacrifice communication networks, feedback loops, participatory decision making and complex problem-solving under the pressures of chronic stress and in doing so, lose healthy democratic processes and shift to innovation and risk-taking resulting in an inability to manage complexity. This requires leadership buy-in and immersion in the change process, an increase in transparency, and deliberate restructuring to ensure greater participation and involvement.

Crisis-driven organisations sacrifice communication networks, feedback loops, participatory decision making and complex problem-solving under the pressures of chronic stress and in doing so, lose healthy democratic processes and shift to innovation and risk-taking resulting in an inability to manage complexity. This requires leadership buy-in and immersion in the change process, an increase in transparency, and deliberate restructuring to ensure greater participation and involvement.

Learn more about trauma-informed organisational change from our book Trauma Informed Behaviour Support which you can access by scanning the QR code

Restoring Sanctuary

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: Let me play devil’s advocate for a bit. I can hear some of the educational leaders reading this saying, “Well, that’s very nice for you, Sandy, but we’ve got parents at our door complaining, we’ve got disruptive students, teachers threatening union action, and we don’t have an endless resource of money.” So what are these practices that make for a healthy organisation?

Dr. Bloom: What you’re describing is a failure of imagination. It begins with a vision of what could be possible if we were committed to it. Then you want to mobilise collective action to achieve that goal. What’s happening here because of the ACEs study is that various local communities are organising around, knowing we have all of these problems; What would it look like for our community to be healthy? What would the outcomes be? How would we know? And then they move back into what would we need to have that happen?

Money is food to an organisational body, just like food is nutrition for humans. But it isn’t everything; you need more than food to be healthy. There’s a lot of work any community, including a school community, can do about getting better nutrition. This isn’t just about getting money, but organising the way money is spent, looking at where the funding goes, and how to mobilise our families. How do we mobilise the children as resources for creating the healthier environment that we’re all imagining? That means you must include students and parents in that imagining process. It can’t just come from the people that work in the school; it has to include all of the stakeholders.

There are now group methods to begin the imagining process. You get large groups of people together to start the creative process, which helps to make a value space rather than criticism and negativism. The point of conflict then is to figure out how to satisfy all those opposing forces. The best system humans have come up with to do that thus far is Democracy. It isn’t perfect, it’s messy, it’s hard, and it’s time-consuming, but humans will support what they’ve helped to create.

Therefore, if you want to make a change, you have to get all the stakeholders to talk to each other after setting up some basic standards for how people work and conduct themselves in the group. I teach a lot, and every class I do, online or in-person, begins with the students deciding what kind of safe environment they want. All students must have a safety plan outlining their responsibility in managing emotions. There are simple things that, even in large groups, you can do to begin the process of reclaiming the territory so that we can build collective skills and intelligence, which is really our only hope.

Teacher Burnout and Self-Care

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: Self-care and burnout. There are many complexities to the issue, but I wanted to get your thoughts about how individual teachers can think about their self-care and advocate in a way that’s sustainable for them to continue being in the profession.

Dr. Bloom: We use a tool called a wellness plan. It’s a commitment that every individual makes to take care of themselves. To try and achieve a better balance between work and home to maintain healthy wellbeing and mental health. It’s part of serving the organisation that, as educators, social service, and healthcare providers, we’re the only tools we have. We have nothing else except our beingness, so we must keep that shiny. We have nothing else except our beingness, so we must keep that shiny. It’s tough because we do emotional labour all the time. We’re picking up other people’s emotions, and emotions are contagious. It’s effortless to get dragged down when you’re seeing dozens of really distressed people. Because of this, you have to do things to leave work at work. Make a ritual transition on your way home where you cleanse yourself and do whatever works physically, psychologically, socially, morally, spiritually, and politically for you. Commit to implementing those things as part of your job responsibility to keep yourself healthy and balance your work and family life. Technology has produced significant problems for people. Some organisations are beginning to implement rules about prohibiting email responses at certain times of the day and on weekends. Having rules about the use of technology is essential, otherwise you will drown in it. When is work ever done? When can you put it away when there are still emails to answer? People can help themselves by having internal rules. Still, the more the organisation supports these rules, the easier it becomes for people to follow through on self-care. It’s helpful if you can share your self-care plan with your teammates so that when somebody sees you escalating, they can say, “Hey, why don’t you go take a walk, and I’ll fill in for you”. Those simple acts of social support mean a great deal. As does having a sense of humour. Being able to laugh and also celebrate our successes are essential for positive wellbeing at work. There’s a lot we can do as individuals, and there’s even more, we can do at an organisational level to keep our equipment and people shiny and healthy.

Trauma in First Nations People

Dr. Krishnamoorthy: I want to touch on trauma in First Nations People. We do some work with some of our Indigenous communities here in Australia. In terms of trauma, they’re often the people who are significantly affected. Some of the issues are historical injustices and structural inequalities that contribute to their intergenerational trauma . I often think people feel overwhelmed and dispirited because their trauma is so significant.

Dr. Bloom: Let me preface this by saying I have a lot of experience working with our African-American communities, less with our native communities. From my experience, working with these communities is that so much of the historical injustice is about an assault on people’s identity and a long-term multi-generational assault on people as being okay, healthy, normal, and creative human beings. It erodes a sense of community identity. The knowledge we have now about trauma and adversity is that by its very nature, these are normalising conversations. It says, “You’re not sick, you’re not bad, you are injured.”

In the case of historical injustice, you have been injured, and your ancestors have also been injured. Despite that, you are a survivor and managed to thrive within the present constraints. You must validate that normality with people to help change that negative identity. I think that’s the beginning of the educational process around trauma and adversity. It normalises these terrible things that people do and how they feel. It says, ‘I can understand this because of what you’ve been through. Now, can I help you in some way to find outlets that are positive and creative that will help you thrive even more? Because you’ve already survived, you’re here, and you’re living’. I think political analysis is crucial. When I started working in residential treatment with kids, I had this fantasy that we would help those children go from being ‘sick and disabled’ to being political and social activists. And that we would create an army of kids who understood what had happened to them, how they had survived it, and what they needed to do to help the rest of the population.

Interestingly, I had an early experience in a high school that again dealt with a plague of adolescents who died by suicide. I was part of a group of adults and students who were brought together to create a task force to address the question ‘how are we going to manage this suicide cluster’? Interestingly, the counsellor who picked the students was a wise guy. He was intelligent and well-informed and understood the issues of trauma and adversity. The students he chose to be a part of this task force to help explain to the adults what was happening with adolescents were all students who had been in treatment. They had all been in substance abuse facilities and knew how to talk to adults. That was my fantasy about the most disturbed kids: if we handle this correctly, the kids will turn into our greatest strengths.

They had learned how to talk about their emotions. They were experienced adolescents, and I thought it was so fascinating the power they had to be the translator to the rest of the adult community about what was going on.

![]() Research Supporting First Nations Students with a Trauma Background in School

Research Supporting First Nations Students with a Trauma Background in School

First Nations students are disproportionately exposed to trauma. However, limited research has explored teachers’ experiences in response to trauma affected First Nations students. Jenna Miller and Emily Berger’s study aimed to explore teachers’ experiences of supporting First Nations students with a trauma history.

response to trauma affected First Nations students. Jenna Miller and Emily Berger’s study aimed to explore teachers’ experiences of supporting First Nations students with a trauma history.

Click or scan the QR code to learn more about this study. This article may be available through your library.

Chapter summary

- Trauma can be defined as when the brain and body are overwhelmed, our physiology is overwhelmed by an experience that causes suffering.

- Everybody’s at risk of experiencing trauma. A public health approach to understanding and managing the impact of trauma is essential in beginning to limit the multi-generational, community wide impact.

- The Sanctuary Model is a trauma-informed organisational change framework that centres on a set of values that are critical in creating an environment that keeps everyone safe.

- The four pillars of the Sanctuary Model include Safety, Emotions, Loss and Future.

- Unsafe or oppositional behaviour needs to be understood as effective coping skills for traumatised people who are trying to cope with feelings that feel worse than self-harming behaviours.

- Organisations are living, adaptive, complex systems that are susceptible to becoming sick, and not functioning well, when under pressure.

- A wellness plan is critical to maintain overall positive wellbeing for staff and to enable staff to have a healthy balance between work and home life.

![]() Creating Presence

Creating Presence

![]() Listen to the full interview on Trauma Informed Education Podcast

Listen to the full interview on Trauma Informed Education Podcast

References

Ayre, K., & Krishnamoorthy, G. (Hosts). (2019, March 26). School climate with Dr. Sandra Bloom [Podcast episode]. In Trauma Informed Education. Soundcloud. https://soundcloud.com/trauma-informed-education/trauma-informed-school-climate-with-dr-sandra-bloom?si=598a7d8bcec94ca883960021a726052e&utm_source=clipboard&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=social_sharing

Ayre, K., & Krishnamoorthy, G. (2020). Trauma informed behaviour support: A practical guide to developing resilient learners. University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/traumainformedpractice/

Crawford County Human Services. (2016, March 15). ACES Primer HD [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ccKFkcfXx-c

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(92)90081-J

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16 (4),681–694. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00032325

Esaki, N., Benamati, J., Yanosy, S., Middleton, J. S., Hopson, L. M., Hummer, V. L., & Bloom, S. L. (2013). The Sanctuary Model: Theoretical framework. Families in Society, 94(2), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.4287

Felitti, V., Anda, R., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., Koss, M., & Marks, J. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Miller, J., & Berger, E. (2022). Supporting First Nations students with a trauma background in schools. School Mental Health, 14(3), 485-497.

TEDxTalks. (2012, March 22). TEDxObserver – Robin Dunbar – Can the internet buy you more friends? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=07IpED729k8

Terr, L. (1992). Resolved: military family life is hazardous to the mental health of children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(5), 984-987. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1097/00004583-199209000-00029

Terrasi, S., & De Galarce, P. (2017). Trauma and learning in America’s classrooms. Phi Delta Kappan, 98(6), 35-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721717696476

The MacKillop Institute. (n.d.). Sanctuary’s S.E.L.F. Framework. https://www.mackillopinstitute.org.au/resources/sanctuary-self-framework