15 Psychology in the Military

WGCDR Gerard J. Fogarty; COL (ret.) Peter J. Murphy; COL Neanne Bennett; and MAJ Anne Goyne

Introduction

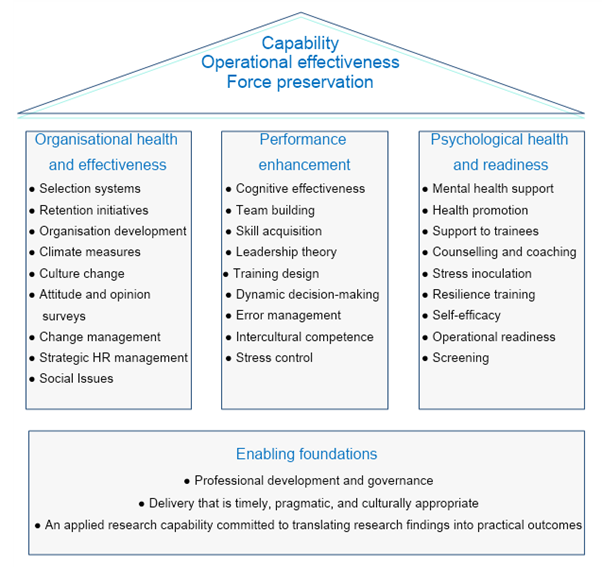

This chapter provides an overview of the practice of psychology in the Australian Defence Force (ADF) from a career perspective. The range of avenues and opportunities available to psychologists may come as a surprise to those unfamiliar with the ADF and the wider Department of Defence. This chapter begins with a historical overview that shows military psychology as one of the original drivers of the profession of psychology both here in Australia and overseas. This section takes readers from the introduction of psychological testing in the Permanent Air Force (later the Royal Australian Air Force) in 1940 through to the present day, where psychological support has three pillars reflecting the core components of service provision: organisational health and effectiveness, performance enhancement, and psychological health and readiness (see Figure 15.1).

The second section illustrates how developments in military psychology were reflected in the civilian world where psychology was emerging as a profession, to the point where the title ‘psychologist’ is now reserved by law for those who are registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra). The ways in which psychology careers in the military mesh with the AHPRA registration standards is a continuing theme in the chapter.

Psychologists in the ADF have always worked for a particular Service (Navy, Army, or Air Force) – either in uniform or as members of the Australian Public Service. While the Services have similar approaches, the platforms underpinning these Services are very different, and the way psychologists work in these fields is also unique to each Service. The third section of this chapter focuses on career opportunities for psychologists in these different branches.

Then, in the final two sections, we describe a small sample of the many projects undertaken by defence psychologists in recent years.

Historical overview of Military Psychology in Australia

The Early Years

It may seem odd to include a history segment in a chapter that deals with career opportunities in the modern day Defence Force, but if you’re considering a career working in the Defence Force, it’s helpful to know that while it’s not in the spotlight today, military psychology had an enormous influence on the development of clinical psychology (recovering from trauma), neuropsychology (head injuries), organisational psychology, psychometric testing, selection, management), counselling psychology (rehabilitation and career counselling), human factors (improving human-equipment connectedness), educational psychology (group training methodologies), and social psychology (leadership, team work). Perhaps no other institution has been as inextricably linked with the development of the profession of psychology as the military (Driskell & Olmstead, 1989).

The origins of military psychology go back to World War I when huge numbers of recruits needed to be allocated to areas that matched their skills, knowledge, and abilities. The Second World War did even more to push psychology to the forefront. As early as 1940, high failure rates in flying training led the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) to implement psychological assessment protocols for pilot selection. Similarly, in 1942, the Army established psychology testing sections across Australia in response to unacceptably high failure rates among recruits. These small units – operating as the Army Psychology Service – provided advice on job allocation and reallocation, investigations into indiscipline, clinical examinations, and advice to officer selection boards (Owens,1977). An evaluation of the Army’s new ‘scientific’ selection process revealed an impressive reduction in training failures (Menezes, 2009).

By 1943, psychologists were providing rehabilitation services and vocational guidance for repatriated veterans. Other emergent tasks included training for operating complex systems, accident investigation, and foreign language training. The demands created in the context of war clearly identified the importance of the profession to the military. During the post-WW2 period, psychologists continued to contribute to military capability in a wide range of areas – so much so that the raising of the Australian Army Psychology Corps (AA Psych Corps)[1] in 1952 entrenched psychology as an essential component of the Army’s support services. An account of these developments from an insider’s perspective can be found in Campbell (1977).

In this postwar period, the roles and tasks of both uniformed and civilian military psychologists included support to recruitment, personnel appraisal and reporting, and advice on military performance enhancement, covering areas such as morale, leadership, and mental health. Many of the processes currently taken for granted in personnel management such as occupational testing, assessment centres, survey research, and the concept of standardised selection methods were developed by psychologists in military settings. Over time, defence psychology provided professional services to other government departments – notably the Antarctic Division (selection and debriefing of expeditioners), the Australian Federal Police (specialist selection), and branches of the intelligence community. Military research also became a particular focus for Service psychology organisations, providing an evidence-base for military personnel management. Examples of military research are presented later in this chapter.

As another sign of their acceptance into the Defence organisation, during the Vietnam War, AA Psych Corps personnel began to operationally deploy with larger scale Army contingents. Army psychologists served in Vietnam, providing support to ‘hearts and minds’ operations, mental health care, and personnel management. The surge of peace support operations from the early 1990s provided increased opportunities for operational support by psychologists and psychological examiners. Roles included pre-, during- and post-operational psychological screening, field research into the human dimensions of operations, contributing to the wellbeing and performance of deployed personnel, and preparing veterans for transition home (Murphy et al., 2003). The deployment of troops into East Timor in 1999 set the pattern for present-day involvement with operational deployments. Psychological screening and individual interviews for troops returning to Australia became routine, as did the provision of psychological support to troops and commanders in location during deployments (Tuppin et al., 2017).

The Three Pillars

A substantial integration of the individual Service psychology agencies in the mid1990s led to the formation of the Defence Force Psychology Organisation (DFPO). The stated mission of defence psychology was to enhance ADF capability, operational effectiveness, and force preservation through timely, pragmatic, and culturally appropriate psychological support across all levels of the organisation. The model for the delivery of psychological support in the ADF had three pillars reflecting the three core components of service provision: organisational health and effectiveness, performance enhancement, and psychological health and readiness (Murphy et al., 2010).

Each pillar contributes to the three mission outcomes listed at the top of the model. For example, force preservation spans the three pillars because it’s not just about improved retention (organisational health and effectiveness) – it also includes prevention of accidents (via enhanced performance) and faster adjustment and improved resilience when deployed (health and readiness). Figure 15.1 also lists typical tasks and issues associated with each of the pillars and shows the three major enabling foundations for effective delivery. Several human science sub-disciplines provide the professional bases of each pillar. For example, performance enhancement tasks utilise expertise from the domains of human factors, cognitive psychology, psychophysiology, social psychology, and sports psychology. The current delivery of psychological support to the ADF is captured within these three pillars and supported by enabling factors such as research and governance (Murphy et al., 2010).

Increased Emphasis on Mental Health Support

The DFPO was disbanded in 2012, and some elements of the psychology workforce were transitioned into the newly established Joint Health Command (JHC), while other parts of the workforce remained within the Army, Navy, or Air Force. A major reason for Army psychology positions being moved to JHC was the changing strategic environment and continuing operational tempo, which contributed to an increasing emphasis on policy and mental health service provision. The ADF – led primarily by Army psychology – has established itself as a leader in the area of mental health reform. The increased emphasis on psychological health and readiness over the last decade has also reinforced the need for leadership to share the responsibility associated with preparing and supporting ADF members across their career. There are dedicated areas in the Army (Career Management) that still look after selection, retention, and workforce planning. The Directorate of People Intelligence and Research has taken on the functions of attitude surveys. A lot of this work now sits under an expanded functional command. In this respect, the other two pillars have continued to have an important role. Qualifications in organisational psychology, for example, are still highly valued in the Air Force, and all three services are interested in performance enhancement. The Army has no preference about what someone chooses to specialise in – organisational, clinical, health, etc. – but as a uniformed military psychologist there is a requirement to be proficient and ready to work across the three pillars. Examples are included later in this chapter.

The Growth of Psychology Outside the Military

To supplement this historical overview, it’s instructive to gain some perspective on how developments inside the military have matched developments in the profession of psychology outside the ADF.

The Australian Psychological Society

Psychology was still a young discipline at the outbreak of WWII. Sydney University was the only institution with a Chair in Psychology at the start of WWII (Turtle, 1985). However, during the years when psychology was gaining a foothold in the ADF, it was also establishing itself in the wider Australian community. Many distinguished psychologists served in our military during WW2. In the postwar period, 12 of the first 13 officers of the Australian Army Psychology Service became professors of either psychology or education in postwar Australia. The 13th became the Director General of Education in New South Wales (Kearney & Hall, 1996). The formation of an Australian branch of the British Psychological Society in 1944 – which became the Australian Psychological Society (APS) in 1966 – represented the profession in the civilian world. In the APS book celebrating its first 50 years as a Society, much credit is given to the Australian Army Psychology Service for bringing together Australia’s most established and experienced psychologists (Heywood, 2018).

Professional Registration

The missing link in this chain was registration. In 1966, Victoria became the first state in Australia to introduce legislation protecting the title of ‘Psychologist’. Other states followed Victoria’s lead, with ACT the final state/territory to introduce registration in 1995. In 2010, Australia adopted national registration for health professionals, and psychology became part of the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS). The Psychology Board of Australia is now one of 15 health-related boards supported by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra). As a consequence of these developments, to use the title ‘Psychologist’ in Australia one must be registered with Ahpra. This restriction applies to the military and civilian psychologists working for the ADF. A brief note on training requirements is therefore in order.

To become eligible for general registration, the minimum qualification is a six-year sequence of education and training, the first four years of which are completed in an accredited university program. At the time of writing, the standard for general registration is being altered so that from June 2022, the first five years of the sequence will have to be undertaken through a university. In addition to the general registration standard, Ahpra allows psychologists to gain an area of practice endorsement (AoPE). To be eligible to apply for endorsement, a psychologist must have an approved qualification accredited at sixth-year or higher in one of the nine approved areas of practice, hold general registration as a psychologist, and have completed a period of Board-approved supervised practice through the registrar program. This information is important to psychologists considering a career in the military because the services differ in terms of entry requirements. These differences will be covered in the following section where the career opportunities in each of the branches of the ADF will be treated separately.

Careers in Psychological Science in the ADF

To cope with its vastly expanded role, military psychology in the ADF has developed into a complex organisation with a mix of personnel, roles, agencies, and associated career paths. In the following sections, we describe the career opportunities that are available in each of the agencies.

Military Psychology through the Army

Full-time Uniformed Psychologists

The Australian Army is the largest of the three services and therefore has the most psychologists. Army psychologists are commissioned as Army officers and, accordingly, are required to follow a code of conduct and are bound by military law and customs. Positions in the Australian Regular Army Psychology Corps (AA Psych Corps), range in rank from Lieutenant to Colonel. The Head of Psychology Corps is the rank of Colonel, and the position’s responsibilities include the provision of strategic-level advice and policy guidance on mental health and psychological matters to senior commanders. Australian Regular Army (full-time) psychologists can be commissioned after completing a recognised five-year program, with a further sixth year undertaken as an internship within the organisation. For those who followed this pathway to general registration, completion of the National Psychology Exam before applying for general registration is also required.

Once registered, the Psychology Board of Australia requires psychologists to maintain, improve, and broaden their knowledge, expertise, and competence through professional development. Continuing professional development (CPD) is therefore a career-long commitment also strongly supported within Defence. To familiarise them with Army life, new AA Psych Officers undertake a Special Service Officer course (SSO) at the Royal Military College (RMC). Once successfully completed, they are paneled for a Regimental Officer Basic Course Psychology (ROBC). To progress to a higher rank in the Corps, Army psychologists must also complete the Regimental Officer Advanced Course (ROAC). Both courses are profession-based and focus on the high-level skills needed to provide tailored psychology support and services across the organisation. Management and leadership skills are also included because, as officers, administrative and leadership responsibilities are part of the psychologist’s role. In addition to the ROBC and ROAC, there are ongoing opportunities to attend workshops and training programs to ensure all Army psychologists deliver the services outlined in the model shown in Figure 15.1. There’s also support for conference attendance where presentation of new techniques and research findings is encouraged. It would be difficult to find another organisation that offers so much profession-specific training for its members.

Throughout their career, Army psychology personnel also undertake general military training courses (starting with the SSO course), including junior and senior leadership and command courses. Moreover, they’re required to pass annual tests of physical fitness (including dental and medical) and weapons handling. As is the case with their professional qualifications, refresher training is embedded into the military training curriculum. Full-time Army psychologists also update their knowledge, skills, and fitness by participating in annual all-Corps training programs.

Army psychology officers are ultimately employed to enhance the effectiveness of soldiers, teams, and leaders through the application of evidence-based psychological principles. Their knowledge of human behaviour is highly valued across a range of Defence contexts and is utilised in mental health, recruitment and selection, training, human factors, reviewing organisational structures, as well as in psychological testing and measurement. There’s also increasing demand for skills in fostering psychological resilience and enhancing human performance (individuals and teams), and a requirement to be able to draw on evidence-informed scientific knowledge and apply this at a practical level. Employment as a psychologist in AA Psych Corps is varied and psychologists come from a broad range of backgrounds and specialisations. Army psychologists are required to develop an adaptable and eclectic skills base to allow them to operate across the three pillars. This breadth of experience is necessary for success at higher ranks in the Corps.

Army psychologists can be posted to a range of commands and specialist capabilities, including health, Special Forces, intelligence, research, and aviation. Newly appointed officers are typically employed under the supervision of senior psychologists and are gradually exposed to professional practice within the military. Initial tasks include selection interviewing, post-operational screening, psychological assessment, and counselling of soldiers. With further experience duties expand to include assisting Commanders with supporting and managing personnel through critical incident mental health support, clinical assessment and intervention, occupational analysis, personnel management advice, research such as psychological climate surveys, and the provision of support to deployments. At senior levels, and following completion of the ROAC, responsibilities broaden to include supervision, leadership, training and management of junior psychologists, conduct of group or individual officer selection boards, and contributing to ADF strategic initiatives.

Reserve Army Psychologists

A full-time career in the regular Army is not the only career option for psychologists. The Army Reserve (ARES) has part-time psychology officer positions that are available to those who already have general registration. Reservists complete the Specialist Service Officer (SSO) Course at the Royal Military College (RMC), Duntroon. The SSO course provides ARES psychologists with fundamental knowledge of the ADF’s roles and functions, its command and control, and administration, and develops leadership, basic military skills, and expected officer behaviour to ensure credibility as a professional in the military organisation.

Reservists must also meet the medical, dental, and fitness standards required of full-time Army members. These standards are enforced through annual fitness, medical, and dental checks. From a career perspective, the Army Reserve force is an attractive option for many psychologists. They can hold down a civilian job and devote some time each week to their reserve work, for which they are paid according to a tax-free remuneration scheme. The nature of the work can vary enormously. Examples include counselling for ADF members, running special projects, conducting interviews and assessments, or engaging in research. Reserve members are also expected to maintain military skills and may have the opportunity to engage in field exercises with their units. Reservists – provided they’ve completed the necessary training – can be deployed on active service (military operations) or assist in disaster relief operations in Australia or overseas. Moreover, there may be opportunities to work for the Army on a full-time basis for extended periods. The Defence Reserve Service (Protection) Act 2001 states that employers must not prevent or hinder Reservists from undertaking Defence service. This means that employers are required by law to release employee Reservists to undertake all types of Defence Service, and to continue to employ them on their return. The Act covers training as well as other activities.

Military Psychology through the Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) began using psychologists at the end of WWII to assist personnel returning to civilian life. The employment of psychologists in the RAN stopped for a short period when this transition task was completed. Fortunately, the broader potential of psychological support services to Navy was recognised and led to psychology services being re-established in 1949. Currently, Navy Psychology is responsible for the delivery of operational and organisational psychology services and interventions in Navy units including Navy shore establishments, lodger units, ships, submarines, and aviation. The Navy Psychology workforce comprises APS psychologists and psychology assistants, and Reserve Navy psychologists (some on full-time arrangements).

The three primary roles delivered by Navy Psychology are:

- Organisational Psychology Services – These include the delivery of in-Service and specialist selection services (e.g., submariner and clearance divers), role suitability assessments, training and administrative referrals, and counselling related to work matters. In addition, Navy Psychology provides support to Navy Selection Boards, delivers mental health, resilience and performance training to Navy personnel, and conducts Command interventions and advice (e.g., unit climate surveys).

- Operational Psychology Services – These include the delivery of annual operational mental health screening programs, pre-deployment training, and post-operational mental health screening. Navy Psychology is responsible for the delivery of Critical Incident Mental Health Support (CIMHS) response in the maritime environment.

- Mental Health Services – Mental health and psychology services at sea are delivered only by uniformed psychologists. In response to a Critical Incident in the maritime environment, a Navy Psychology team can be embarked to the ship or nearest port (as a ‘fly in’ team) to conduct a CIMHS response.

The primary role for uniformed psychologists in Navy is to provide mental health services in support of maritime operations. Uniformed psychologist also augment the delivery of psychology services in regional Navy Psychology sections. General registration and five years of employment as a psychologist are requirements for Navy Reserve psychology positions. Upon entry, Reserve Navy psychologists complete the Reserve Entry Officers’ Course (REOC), which teaches new appointees the skills required of a naval officer. Like the Army SSO course at RMC, the REOC fosters a duality of roles – one serves as both a Navy officer and as a military psychologist. Applicants to the Navy Reserve must also meet the same standards of fitness and weapons readiness that apply to all branches of the ADF.

Military Psychology Through the Air Force

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was the first of the three services to employ psychologists during WWII. Like the Navy, psychology support services ended shortly after the war. The Air Force Psychology service was re-established in 1947 with a staff of permanent civilian personnel and some uniformed reservists (Rose, 1958). Today, there are uniformed and civilian Air Force Psychology positions spread across different Air Force bases (Canberra, Sale, Wagga, Williamtown, and Amberley). This core group is supported by additional reserve positions – some of which are classified as clinical and some as organisational. The clinical positions – as the classification implies – provide assessment, counselling, and intervention services on an individual basis. The more numerous organisational positions cover such roles as:

- the delivery of psychology education and training packages

- developing new training material on topics such as resilience, performance enhancement strategies, or organisational culture

- participating in selection processes and panels

- developing and implementing new initiatives to improve the overall wellbeing and effectiveness of the Air Force workforce

- applied research.

Compared with the other services, a key difference with the Air Force Psychology positions – both full-time and reserve – is a preference for psychologists with an organisational psychology background in addition to general registration. The Air Force emphasis on organisational psychology reflects the importance of human factors in a high-risk environment. Those applying for the organisational psychology positions must have completed – or be enrolled in – a Master of Organisational Psychology degree. If they’re in their final year, the application will be accepted but the actual appointment will be delayed until the degree is completed. Air Force Psychology has an internal program for new graduates who have yet to complete the Ahpra registration requirements for an area of practice endorsement (AoPE) in organisational psychology. Applicants for clinical psychology positions share the same requirements as organisational psychologists – a masters degree and AoPE – except in clinical psychology.

Military Psychology Through Civilian Channels

Other ways to become involved in defence psychology are through the public service and consultancy channels. Regarding the former, there are many dedicated psychologist positions in the Department of Defence. The requirement for most of these positions is general registration, although AoPE may be required in some cases. The roles vary widely but fall into one of three pools: security, organisational, and clinical. Another important public sector agency is the Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG). DSTG is a research organisation with a strong emphasis on technology and innovation. Psychologists working for DSTG are civilians, although uniformed psychologists are often involved in their research projects. DSTG has the advantage of being a dedicated research facility with equipment and laboratories that are not found on a military base or an office environment. It provides research-based scientific advice to the ADF and to the national security community. DSTG offers jobs in six major subject fields – one of which is behavioural and social science. DSTG also runs scholarship and placement programs to provide industry experience to students looking for a career in science and technology.

The Department of Defence is not the only department associated with the military that offers positions for psychologists. The Department of Veterans Affairs is another major employer. Entry-level positions for counsellors and mental health workers require provisional registration and the usual security clearances and police checks. This Department also offers opportunities for part-time work, with hourly rates published in the relevant advertisements. The final avenue for engagement with the military that should be mentioned is the role of consultant. There are opportunities for consultancy roles in psychology – primarily in the research domain – but they’re unlikely to be advertised, and won’t, in general, suit early-career psychologists.

Applied Research by ADF Psychologists

The practice of psychology within Defence has always been underpinned by an emphasis on applied research. Defence psychologists are encouraged to undertake research – either as part of their work or to fulfil requirements for higher degrees. This work forms part of a wider international effort supported by organisations such as the International Military Testing Association (IMTA), the NATO Research and Technology Organisation (RTO), and The Technical Cooperation Program (TTCP) that encourage the sharing of military psychological research amongst allied partners.

Prior to conducting research in the ADF, research proposals must be cleared by either the low or high risk Defence research ethics panels. In this section, we highlight examples of research conducted by Defence psychologists. The first example comes from the Organisational Health and Effectiveness pillar in Figure 15.1. The second example comes from the Performance Enhancement pillar, and the third from the Psychological Health and Readiness pillar. The fourth example is a classic study in ergonomics, involving knowledge and skills drawn from organisational psychology and human factors. In each case, we describe the challenge that gave rise to the research, the psychological science knowledge that was applied to the challenge, and the impact of the research.

The Challenge

The prevailing view in Defence was that good commanders should always know what their troops are thinking and feeling without needing to be told. The research evidence suggests otherwise – intuition or ‘gut feel’ is rarely reliable. The challenge was to develop a survey that would give commanders objective feedback about the human dimensions within their unit and to convince them to use this tool, preferably early in their posting.

Applying Psychological Science

The Profile of Unit Leadership Satisfaction and Effectiveness (PULSE) grew out of a collaboration between Canadian Forces and the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to develop a survey tool to assess unit climate in a garrison environment. The original PULSE included purpose-designed and published industrial scales known to measure unit climate at the individual, group, and unit levels. When combined with a comprehensive demographics section, the PULSE climate survey provided a wealth of information on individual and unit performance for commanders.

The Impact

As evidenced by feedback from commanders (Goyne et al., 2008), the original PULSE fulfilled a need for unit commanders and was well-received. The revised PULSE reduced the size of the instrument without losing any predictive validity and established its theoretical base (JD-R), thus enabling Army psychologists to draw upon a rich literature describing how the variables measured by PULSE interacted to influence outcomes such as wellbeing, unit performance, turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and unit morale. Organisational climate surveys like PULSE have a history of blooming quickly and then falling into disuse. That hasn’t happened with PULSE. It remains a voluntary tool that is usually administered at a commander’s request. To this point, almost 20 years after the instrument was introduced, the demand is still strong.

The Challenge

Safety culture became a worldwide issue in the second half of last century following major disasters in the nuclear, chemical, and aviation industries. The response from the human factors section of the psychological community was strong and prompt. The first human error conference took place at Columbia Falls, Maine, USA in 1980. The first International Aviation Psychology Conference took place at Ohio State University in 1981. In 1992, the Australian Aviation Psychology Association (AAvPA) was formed. Journals that focused on safety research appeared, and military aviation psychologists began to understand the individual and organisational factors that contributed to these disasters. The first safety climate instruments appeared in the 1980s and 1990s.

Safety climate refers to the individual’s perceptions of the organisational policies, procedures, and rewards relevant to safety in the organisation. Safety climate is a useful way of monitoring the safety status of an organisation. These developments had their parallel within Defence Aviation. Sixteen soldiers lost their lives in 1996 when two Black Hawk helicopters collided during a night-flying exercise in Townsville. The Black Hawk accident and the subsequent Board of Inquiry was the stimulus for Defence Aviation to develop its own safety climate measures.

Applying Psychological Science

Army psychologists took on this work and began by conducting focus group interviews at aviation bases and deciding what constructs should be measured. The results of this fieldwork enabled psychologists to construct a purpose-designed safety climate survey called the Maintenance Environment Survey (MES). The MES measured organisational and individual factors considered likely to impact maintenance performance. It included scales to assess perceptions of the work environment as well as measures of stress, fatigue, commitment, job satisfaction, positive and negative affect, and error. The first instrument, completed in 1998, was developed for the maintainer workforce only. In subsequent years, the survey also included aircrew.

Impact

After numerous revisions and updates, the current version of the original safety climate measure, called Snapshot, is administered annually to over 15,000 ADF aviation personnel, 2,000 Royal Australian Navy personnel, and approximately 2,000 Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) personnel. Data from the survey is fed back to unit commanders and to high-ranking officers to help gauge the safety status of individual units and larger organisational groups. Psychologists running Snapshot are a mixture of reservists and public servants. They regularly conduct psychometric reviews of the survey, including testing whether the data fits the underlying theoretical model. The results of these checks are reported in journal articles (e.g., Fogarty, et al., 2018), internal technical reports, and conference proceedings (e.g., Cooper, et al., 2016). Statistics from the survey are used by the Air Force to monitor trends and to shape aviation safety policy and procedures.

The Challenge

Workplace bullying and incivility have been issues of concern throughout the Western world. Organisations want to reduce the prevalence of bullying and to build support services for those who have been bullied. The ADF has its own share of these problems. After conducting an extensive review of reported cases of alleged unacceptable behaviour in the ADF – including a review of past investigations into abuse – Rumble et al. (2011) concluded that there was a culture in the ADF of discouraging the reporting of abuse, a tolerance for unacceptable behavior, and a lack of punishment for perpetrators.

Applying Psychological Science

The Australian Defence Organisation (ADO) – which includes both the Australian Defence Force and the Department of Defence – is improving its collection of information on the prevalence of workplace bullying. It began to routinely measure the prevalence of bullying within the organisation through PULSE and Snapshot surveys – which added items covering the topic – and through dedicated surveys such as the Unacceptable Behaviour (UB) Survey. These instruments, particularly the PULSE survey, created opportunities for civilian psychologists working in the Directorate of Occupational Psychology and Health Analysis (DOPHA) to use multivariate analysis to quantify the effects of bullying across different sources (members of the public, coworkers, supervisors, subordinates, and combinations of these sources) and to look for interactions involving factors such as rank, age, and gender (Steele et al., 2000). In further work, using multilevel modelling techniques, Steele and colleagues demonstrated the impact of bullying, not just on individuals, but on the organisational units to which they belong.

The impact

The work of the DOPHA psychologists added to what was already a considerable push within the ADF to reduce bullying. The Commonwealth Ombudsman continues to receive reports of abuse in the ADF, but in the June 2020 report on bullying among recruits (Commonwealth Ombudsman, 2020) it was noted that cases no longer reflect the systemic abuse that was apparent in Defence in earlier periods. The training, reporting systems, and monitoring techniques put in place appear to be working. These strategies embrace the work of experts from a wide range of fields, but the basic science quantifying the debilitating effects of behaviours such as bullying comes from psychological science.

The Challenge

The uniform worn by serving personnel is a key identifying feature of military service. Often recognised for its commonality of colour, pattern, or shape, a uniform’s most basic purpose is to easily differentiate those who serve, and to provide protection in undertaking daily duties. The term ‘military uniform’ covers a broad range of items, including clothing, load carriage, and protective equipment . Known as ‘materiel solutions’, fit, form, function, financial cost, and majority population sizing are important when developing new uniforms. Many of the materiel solutions developed to date are geared towards the anthropometric considerations of a majority male population. However, in early 2016, the ADF opened all combat role opportunities to women. To facilitate this program, materiel solutions were needed that met female anthropometric needs. This need was highlighted in the 2021 NATO Science and Technology Organization report Women in the Armed Forces, NATO Science and Technology Organization (STO) Research on Women in the Armed Forces (2000–Present), which recognised the physiological differences of women and the importance of appropriately designing equipment.

Applying Psychological Science

In 2020, the Australian Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) enlisted their innovation hub Diggerworks to identify clothing, load carriage, and protective equipment materiel solutions suited to women. A critical difference to previous design and development projects was the inclusion of a military psychologist. Grounded by the scientist-practitioner model, the expertise of the psychologist helped shape an evaluation framework (i.e., surveys, focus groups, thematic analysis) focused on the needs of the user and establishing a human-centred approach to the design and development process. The understanding of change management theory and behavioural and cognitive perspectives across career, helped shape educational resources supporting the uptake of new materiel solutions. In 2020, the Chief of Army endorsed several innovative female-specific clothing and equipment options.

The Impact

The input of military psychology in this project helped the design and development of tailored clothing and equipment solutions for military personnel. Applying a strong investigative and analysis framework, the presence of a military psychologist also helped demonstrate the importance of well-designed and fitted clothing and equipment for performance across the career lifecycle. The scientist-practitioner model unlocked a number of user considerations and needs achieving measurable performance outcomes. This human-centred approach resulted in a more holistic and future-focused materiel research and development framework benefiting all personnel.

Defence Psychology in Action

To round out this chapter on military psychology, we describe a selection of major non-research projects that illustrate some of the exceptional work undertaken by military psychologists.

Responding to Tragedy

Military psychologists have a long history of providing support following tragedy. In our example, military psychologists provided support in the aftermath of the Sea King helicopter crash on the island of Nias, Indonesia in April 2005. Nine ADF personnel died in the accident, which occurred during a humanitarian assistance mission. A uniformed psychology officer specialising in aviation human factors was attached to the Accident Investigation Team. Navy Reserve psychologists deployed to provide critical incident mental health support to the crew of HMAS Kanimbla, the ship responsible for transporting and maintaining the helicopter. A team of Defence psychologists provided support to personnel at the accident squadron’s home station. Psychological advice was provided to those working in various roles at the accident site. Where necessary, psychologists provided or facilitated ongoing mental health support. Another psychology officer was a member of the Accident Board of Inquiry, and a number of psychologists from all three services either provided evidence to the Inquiry or helped to implement its recommendations to improve safety systems in the ADF.

Aid to the Civil Community and Humanitarian Responses

Although not its primary role, the ADF can assist the civil community through its capabilities and resources during and after natural disasters or other catastrophic events. These capabilities and resources include providing logistics, communications, transport by sea, land, and air, and health support. An example of this is when uniformed psychologists were rapidly deployed to support the response to the Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria in February 2009. The ADF was again involved in civilian support work following the 2010–11 Queensland floods. Other disasters included flood relief in NSW, Queensland, and Victoria (2011–12) and flood and fire relief in NSW, Queensland, WA, and Victoria (2012–13). The most recent national events resulting in the Australian Government requesting ADF support have been Operation Bushfire Assist 2019–20, and Operation Covid-19 Assist in 2020–2021.

Military psychologists are well-qualified to assist in such situations due to their operational experience in theatres of conflict, where they provide support to personnel routinely exposed to widespread destruction and human suffering. Psychology Support Teams are often dispatched in ‘first contact’ roles to engage with affected individuals or communities. Other psychologists – civilian and Reservist – conduct psychological screening and follow-on support for the hundreds of military personnel who provided assistance to survivors. In these situations, Defence psychologists support the ADF personnel assisting the community and, if the government requests it, provide psychological first aid and support to others who may have been affected.

Deployment-Related Psychological Support

The operational tempo of the ADF grew considerably from the mid1990s. During this period, psychological support to our deployed personnel evolved constantly. Pre-deployment support is concerned with preparing the deploying force – particularly by fostering psychological readiness through training and education. Support during deployment has two main strands: maintaining the wellbeing of ADF people and enhancing their performance. Post-deployment support covers a range of activities, including:

- identifying personnel in need of professional assistance and taking appropriate action

- validating the deployment experience of personnel by fostering a sense of meaning and satisfaction from their role

- preparing personnel for the challenges of homecoming

- demonstrating ADF concern for its members

- enhancing understanding of the human dimension of operations to assist future training, support activities, and policy.

Conclusion

Since its beginnings during WW2, psychology in the military in Australia has made a major contribution to the profession and to the Australian community generally. Early on, that contribution was direct, with ADF psychologists moving from Defence positions into highly influential roles in universities, the community, and the Australian Psychological Society. In more recent years, that pipeline continues with the majority of former Directors moving into highly influential roles within government and non-government sectors. At a more general level, military psychology is helping the profession to deal with issues it hasn’t confronted before. Since the late 1980s, psychologists – both civilian and uniformed – have had the opportunity to work with thousands of troops deployed on peacekeeping, disaster relief, and military operations around the world, some of them on multiple occasions. Their expertise in dealing with deployment-related issues has made them well-equipped to assist local communities in coping with floods, bushfires, and other disasters. The lessons learned through this work are informing training programs for many psychologists and have led to the formation of groups such as the Military and Emergency Services Psychology Interest Group – one of the Australian Psychological Society special interest groups.

Military psychology has come a long way from the post-World War II days when its main focus was recruiting and psychological assessment. The greater emphasis on the mental health and wellbeing of current and ex-serving personnel has led to defence psychology being a leader in mental health initiatives. It has been instrumental in contributing to a greater understanding of the mental health impacts of operational deployment, human responses to trauma, and coping techniques – particularly psychological resilience. Since the 1990s, many organisations have sought advice from the ADF about how to foster mental health and wellbeing in their own workplaces. It’s worth stressing that opportunities for psychologists in the military are not confined to mental health. Uniformed psychologists can improve their management and leadership skills, develop human factors knowledge by working in specialised occupational areas such as aviation, engage in applied research, and find roles that involve a blend of clinical, organisational, and human factors skills. There are few organisations that offer such a wide range of opportunities. Most importantly, continuing development and refresher training is also widely available to those in uniform.

In this chapter, we’ve been careful to point out that job opportunities in the ADF don’t necessarily involve putting on a uniform. The range of duties is more restricted for civilian psychologists – for example, they can’t be deployed – but there are still plenty of opportunities available. Civilian psychologists also have the opportunity of joining one of the services as a reservist – in which case they get to experience activities that would otherwise be unavailable (e.g., deployment). Reservists, however, are unlikely to experience the three-yearly posting cycle that allows permanent uniformed psychologists to develop skills across such a wide range of activities. We have also been careful to point out that there are differences across the services in terms of duties and expectations for psychologists.

Regardless of the service or the uniformed/civilian mix, Defence psychologists aim to enhance ADF capability and improve the psychological wellbeing of ADF personnel. To do this, they need to employ a range of clinical, counselling, organisational, educational, human factors, and social skills. Their longer-term goal is to protect Australia and its national interests. This is a worthy goal and one that gives a sense of meaning to the work they do. We hope this chapter has aroused your interest in the career possibilities available in defence psychology in Australia.

Contributors

The following authors (listed in alphabetical order) contributed to this book chapter:

- WGCDR Donna Merckx, Deputy Director, Air Force Psychology, Royal Australian Air Force

- Dr Nicole Steele, formerly with the Directorate of Occupational Psychology and Health Analysis, Joint Health Command, Department of Defence

- MAJ Sarah Watson, Operational Performance, 1st Psychology Unit HQ, Australian Army

- Ms Jennifer Wheeler, Director of Navy Psychology, Canberra, Australia

Send us your feedback: We would love to hear from you! Please send us your feedback.

Copyright note: Permission has been granted by Peter Murphy to use Figure 1.

References

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands–resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Campbell, E. F. (1977, October 22). How it all happened. Australian Army Psychology Corps Newsletter: Twenty-Five Years, 10–13 [Unfiled archived Corps newsletter]. Australian Army Psychology Corps Archives.

Manthorpe, M. (2020). Inquiry into behaviour training for Defence recruits (Report No. 04/2020). Commonwealth Ombudsman. https://www.ombudsman.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/111253/Defence-Force-Ombudsman-Report-Inquiry-into-behaviour-training-for-Defence-recruits.pdf

Cooper, R., Fogarty, G. J., & McMahon, S. (2016, November 8–10). Assuring safety: The role of organisational surveys [Conference session]. 12th International Symposium of the Australian Aviation Psychology Association (AAvPA), Adelaide, Australia.

Driskell, J. E., & Olmstead, B. (1989). Psychology and the military: Research applications and trends. American Psychologist, 44(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.1.43

Fogarty, G. J., Cooper, R., & McMahon, S. (2018). A demands-resources view of safety climate in military aviation. Aviation Psychology and Applied Human Factors, 8(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1027/2192-0923/a000141

Goyne, A., Lake, R., Riley, M., & Johnston, B. (2009). Taking the Pulse of your unit: A command support tool for assessing unit climate. In P. Murphy (Ed.), Focus on human performance in land operations, (pp. 70–77). Department of Defence.

Heywood, J. (2018). The power of minds: Celebrating 50 years of the Australian Psychological Society. Bounce Books.

Kearney, G., & Hall, W. (1996). Military Mentor. The Bulletin of the Australian Psychological Society, June, 17–18.

Murphy, P. J., Collyer, R. S., Cotton, A. J., & Levey, M. (2003). Psychological support to Australian Defence Force operations: A decade of transformation. In G. E. Kearney, M. C. Creamer, R. Marshall, & A. Goyne (Eds.), Military stress and performance: The Australian Defence Force experience (pp. 57–82). Melbourne University Press.

Murphy, P., Hodson, S., & Gallas, G. (2010, April). Defence psychology: A diverse and pragmatic role in support of the nation. InPsych. http://www.psychology.org.au/publications/inpsych/2010/april/murphy/

O’Keefe, D., Urban, S., & Darr, W. (2019). Psychology in the military. In M. E. Norris (Ed.), The Canadian handbook for careers in psychological science. eCampusOntario. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/psychology-in-the-military/

Owens, A. G. (1977). Psychology in the Armed Services. In M. Nixon & R. Taft (Eds.), Psychology in Australia: Achievements and prospects (pp. 202–213). Pergammon Press.

Rumble, G. A., McKean, M., & Pearce, D. C. (2011). Report of the review of allegations of sexual and other abuse in Defence: Facing the problems of the past. Dept. of Defence and DLA Piper (Firm).

Steele, N. M., Rodgers, B., & Fogarty, G. J. (2020). The relationships of experiencing workplace bullying with mental health, affective commitment, and job satisfaction: Application of the job demands control model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), Article 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062151

Tuppin, K. A., Sinclair, L., & Sadler, N. L. (2017). The three pillars of Australian Army psychology: To serve with a strong foundation. In S.V. Bowles & P. T. Bartone (Eds.), Handbook of military psychology: Clinical and organizational practice (pp. 489–500). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66192-6_30

Turtle, A. M. (1985). Psychology in the Australian context. International Journal of Psychology, 20(1), 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1464-066X.1985.tb00017.x

Please reference this chapter as:

Fogarty, G., Murphy, P., Bennett, N., & Goyne, A. (2022). Psychology in the military. In T. Machin, T. Machin, C. Jeffries & N. Hoare (Eds.), The Australian handbook for careers in psychological science. University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/psychology-in-the-military/

- A 'corps' is an administrative grouping of personnel within an armed force with a common function. This arrangement is still unique among the armies of the English-speaking world. ↵