10 Industrial, Work, and Organisational Psychology

Peter Macqueen and Tony Machin

Introduction

‘Psychology is a science and a profession’ (O’Gorman, 2007, p. 1). And thus begins John O’Gorman’s book titled Psychology as a Profession in Australia. In presenting subsequently as a panellist at QUT in Brisbane during Psychology Week 2011, O’Gorman expanded on this by observing that ‘Psychology is about people’. He also reminded the audience – which included school students – that mental health is only one small, albeit important, part of psychology’s relationship with human existence. On the other hand, work is an integral part of life for nearly all people, extending over many decades. Industrial, work, and organisational psychology (IWOP) plays an important role in understanding the interplay between people and organisations, and even society, through the lens of work. It helps us understand the impact of work – beyond the economic component – and with designing appropriate systems and interventions. IWOP strives to enhance organisational effectiveness while keeping the wellbeing of the individual clearly in focus. The following sections will describe some of the different areas where industrial, work, and organisational psychology can be applied, and outline the role of professional organisations. We also highlight the wide range of work contexts where people can apply their expertise in IWOP, and suggest some suitable career pathways into this profession.

The discipline and profession of industrial, work, and organisational psychology

While the term ‘organisational psychology’ is used mainly in Australia, as well as in New Zealand/Aotearoa, there are several alternative designations in use elsewhere. North America, Singapore, Japan, and South Africa use ‘industrial and organizational psychology’, whereas Europe and Brazil use the label ‘work and organizational psychology’. In the UK, ‘occupational psychology’ is the term most frequently used, while in Germany, there is a section of the German Psychological Society (DGPs) called ‘Work, Organizational, and Business Psychology’. Finally, Chile has a ‘Society of Psychology and Organizational Behavior’. It might seem confusing to students, employers, profession regulators, and to elected members of the government that there are so many different terms used to describe this profession. We recognise that this confusion may have contributed to an ongoing struggle to demonstrate its impact.

It seems timely for a new, overarching term to emerge: industrial, work, and organisational psychology (IWOP). [1] In early 2021, a draft of the IWOP Declaration of Identity (Kożusznik & Glazer, 2021) was released following consultation with various participants and bodies over several years. The introduction to this Declaration states that ‘The IWOP profession is concerned with both individual work-related wellbeing and effective performance’. It also claims that IWOP is now considered a profession, and that professions affect societies. The introduction to the Declaration continues with ‘IWOP has a responsibility as a profession to support difficult decisions at the societal, organizational and group level, so as to always ensure that workers and worker-eligible people are reaping benefits rather than harm, by their work engagements’.

The IWOP Declaration of Identity is expanded through the inclusion of ten draft statements organised around four major themes: communication, contextualisation, dissemination, and integration. There are various elements within each of these statements, but the key components include the following:

- We value wellbeing and human welfare.

- We bridge organisational science and practice.

- We ideate and innovate in all working situations and environments.

- We balance individual needs with organisational goals.

- We strive to employ ethical, evidence-based influence on decision-makers.

- We ask rigorous and relevant questions to address critical issues.

- We communicate broadly and are active partners in social dialogues.

The declaration makes a strong case for the IWOP profession to be recognised as contributing to all areas of work, whether from an employee, organisational, or governance perspective.

The development of the IWOP Declaration of Identity involves many organisations, and reflects the desire for global cooperation that is a very positive feature of IWOP. The Alliance for Organizational Psychology is a ‘federation of Work, Industrial, & Organizational psychologies from around the world’. The main members are four organisations: the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP), the European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology (EAWOP), the International Association for Applied Psychology (IAAP) Division 1 – Work and Organizational Psychology, and the Canadian Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (CSIOP). In early 2020, the Alliance created a new global partnership called the ‘Big Tent’, and many IWOP societies around the globe have now joined the Big Tent, including the New Zealand Institute of Organisational Psychology, part of the New Zealand Psychological Society (NZPsS).

As of April 2022, there are sixteen network partners in the Alliance. Currently, Australia is represented only by the Society for Industrial and Organisational Psychology Australia (SIOPA). Formed in 2016, it’s an autonomous Western Australia-based body which is not part of the Australian Psychological Society (APS) and is not affiliated formally with SIOP in the USA. However, at the time of preparing this chapter, the College of Organisational Psychology (COP) – one of the colleges within the peak professional body, the APS – was not part of the Alliance Big Tent. Given the challenges and opportunities facing IWOP in Australia, as well as globally, we (the authors) believe it’s important for mainstream organisational psychology in Australia to make every effort to join the Alliance as a matter of priority, initially via the Alliance ‘Big Tent’.

The final organisation we want to highlight in this section is a relatively new organisation: the Asian-Australian Organisational Psychology Inc (AAOP). This organisation aims to enhance the Asian-Australian organisational psychology identity and to promote cultural equality for Asian-Australians. This reflects a more specific focus than the other industrial, work, and organisational psychology bodies we have reviewed.

What does an IWO psychologist do and where do they work?

You can learn more about becoming an IWO psychologist by:

- talking with IWO psychologists – perhaps by attending a local meeting

- searching for information online

- talking with a psychology academic or careers advisor

- perusing texts (particularly handbooks – we particularly like the three-volume The SAGE Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology 2nd ed.) which provide material reflecting the breadth, depth, and growth of IWOP globally. The astute student will strive to secure insights from local as well as North American, UK and European publications, and even beyond.

- joining or following a LinkedIn group such as Organisational Psychology in Australia or SIOP

- reading the eight career profiles towards the end of this chapter.

Another useful source is O*NET OnLine. Not only is this a very useful online tool for career exploration, but it’s also considered an essential starting point for any work or job analysis. See the text box on Using O*NET OnLine below for some suggestions about how to use this site. While you’re researching this field, it’s important to note that IWOPs work under many different job titles. You’ll see some examples of reported job titles in the report.

Using O*NET OnLine

- Go online to www.onetonline.org

- Enter “organisational psychologist” in the Occupation Search box

- Click on ‘Industrial-Organizational Psychologists’ and read carefully, noting that this is all-encompassing, and that an organisational psychologist is very unlikely to be engaged in all of the tasks listed (there are 24 in total)

- Complete the O*NET Interest Profiler by going to https://www.mynextmove.org

- Click the ‘Start’ button under ‘I’m not really sure’

- You’ll see results that align with the well-known Holland’s hexagon model of vocational choice (RIASEC) and be able to explore recommended vocational choices based on your levels of education, training, and experience

The APS COP website (2021) lists the following areas of practice where IWO psychologists can demonstrate their expert skills and knowledge:

- workforce planning and role definition

- recruitment and selection (including psychological testing and assessment)

- learning and development

- coaching, mentoring, and career development

- workplace advice and advocacy

- change management

- organisational development

- measuring employee opinions and other workplace research

- performance management

- wellbeing, stress, and work-life balance

- occupational health and safety

- human resources program evaluation

- consumer behaviour and marketing.

IWO psychologists work in a variety of settings. While some are employed in government departments, the Australian Defence Force (see Chapter 15), or large commercial enterprises, many also work in academia and as consultants. Such consultancies can be small (such as sole traders) or much larger and comprised of fellow consultants from human resources, industrial relations, and business in general. Recent technological advances in fields such as personnel assessment and selection mean IWO psychologists may now be working with software engineers or data scientists. Research and consulting centres incorporated as part of a university are increasing in number. One of the examples later in this chapter is from Sharon Parker, Director of The Centre for Transformative Work Design at Curtin University in Western Australia. The field of work design can be added to the COP list above and represents an additional area of opportunity for IWOPs.

This raises an important issue: the publicised impact of some of our IWO psychology scholars. On November 10 2021, The Australian released its Research Magazine 2021 containing a list of 40 ‘superstars of research’. Two of the five lifetime achievers in research nominated for the Business, Economics & Management category, Neal Ashkanasy and Sharon Parker – both IWO psychology scholars – share their stories later in this chapter.

Another key area missing from the COP list is human factors. The University of Adelaide offers a Master of Psychology (Organisational and Human Factors), and several Australian IWO psychologists work as human factors specialists within the aviation industry and road traffic and safety authorities. One such a psychologist, Allison McDonald, the Managing Director of SystemiQ, shares her story later in this chapter. Human factors are also referred to as ‘engineering psychology’ (Rogelberg, 2007) or ‘human engineering’ (Landy & Conte, 2004). In essence, the field of human factors endeavours to align the demands of the work environment with the characteristics and requirements of individuals. This can be accomplished via knowledge of human capabilities in designing effective processes, system linkages, and training initiatives. The addition of tools and techniques to enhance performance also forms part of the overall approach to human factors or ergonomics. Furthermore, we (the authors) are confident that IWOPs will make an important contribution to the growing field of cyberpsychology. Dalal et al. (2021) outline how organisational researchers could contribute to the important area of cybersecurity, as well as how this could represent a new and challenging area of professional practice.

The discipline of human factors highlights key issues such as human decision-making and error management, and stresses that these are a critical part of system design. When we consider human factors, it’s important to examine how the person and the environment (or system) can interact to influence human behaviour. Kurt Lewin’s famous field theory (1951) summarised this approach in an equation B=f (PxE), where behaviour is described as a function of the person and their environment. The P-E perspective is also discussed in Chapter 2 of this book. The notion of ‘fit’ between person and environment underpins one of the traditional mainstays of IWO psychologists: personnel selection – a topic addressed later in this chapter. Further, several large global organisations adapt this approach through the mantra of ‘systems shape behaviour’, and some of these organisations are focused on the design and implementation of comprehensive behaviourally-oriented leadership and management systems (e.g., Macdonald, Burke & Stewart, 2006).

The history of IWO Psychology: with an Australian focus

Kelloway (2019) claims the first two books in IWO psychology were Increasing Human Efficiency in Business (Scott, 1911) and Psychology and Industrial Efficiency (Münsterberg, 1913). In the early 1900s, economic and social trends resulted in a glorification of industrialisation and progress (Viteles, 1932). Any field that claimed to advance the interests and tenets of capitalism was widely accepted. We suggest that anyone wanting to understand the history of IWO psychology consult:

Koppes Bryan, L. L. (Ed.). (2021). Historical perspectives in industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429052644

Vinchur, A. J. (2018). The early years of industrial and organizational psychology. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781107588608

Koppes, L. L. (Ed.). (2007). Historical perspectives in industrial and organizational psychology. Routledge.

Vinchur (2018) provides a good deal of information beyond the USA, while Koppes (2007) and Koppes Bryan (2021) are very US–centric. The contributors to the 2021 edition are solely North American, as are the five testimonials in the book. Students can also consider the European perspective provided by Chmiel, Fraccaroli and Sverke (2017) in An Introduction to Work and Organizational Psychology: An International Perspective (3rd ed.). Similarly, a useful book with many well-known UK authors is Organizational Effectiveness: The Role of Psychology (Robertson, Callinan & Bartram, 2002).

Zickar and Gibby (2021) have developed four themes which they claim differentiated IWO psychology in the USA from other countries and cultures, while also distinguishing it from other disciplines such as industrial sociology, labour economics, and industrial engineering. These four themes are:

- an emphasis on productivity and efficiency

- an emphasis on quantification (and quantitative versus qualitative methodologies)

- a focus on selection and differential psychology

- the interplay between science and practice (this issue is addressed later in this chapter).

When reflecting on his highly productive career, Sackett (2021) noted the increasing tendency to focus on ‘organizational’ psychology rather than ‘industrial’ psychology. Industrial psychology often examines individual performance or agency and is more likely to use sophisticated measurement and quantitative methodologies. Personnel selection is a good example of ‘industrial’ psychology. Further, Luthans (2017), albeit an organisational behaviour scholar (i.e., an ‘O’ person), called for ‘dropping the outdated term “industrial” from I-O’ (p. 579). Thus, Zickar and Gibby (2021) needs to be evaluated against this background.

Feitosa and Sim (2021) provide a perspective on IWOP beyond the USA, but include very limited information on Australian history, and are incorrect in citing a 2006 publication stating psychologists have to register with the Psychology Board of Australia. This Board was only established in 2009. A more substantial discussion of Australian IWOP is provided by Hesketh, Neal and Griffin (2018). Bordow (1971), using a survey completed by 94 respondents, contributed an interesting snapshot of the state of the ‘industrial psychologist’ in Australia fifty years ago in terms of education, employment, and job functions. However, for a relatively recently published history of psychology in Australia, Buchanan (2012) provides a good starting point.

Vinchur (2018) claims Bernard Muscio was Australia’s leading early proponent of improving efficiency through use of industrial psychology. In 1916, Muscio ‘delivered a series of talks on industrial psychology in Sydney, which later appeared in print as Lectures in Industrial Psychology (1917)’ (Vinchur, 2018, p.163). O’Neil (1977; 1987) previously had elevated Muscio to pioneer status in Australian psychology. A Sydney graduate, Muscio undertook further studies in mental philosophy at Cambridge and then commenced pioneering work in industrial psychology in the UK with the First World War Industrial Fatigue Research Board (later the Industrial Health Research Board). Returning to Australia in the early 1920s, he delivered a series of lectures to the Worker’s Educational Association in Sydney, with the publication of these lectures being viewed as groundbreaking, globally (O’Neil, 1977). Vinchur (2018) noted that Muscio had once been an advocate of scientific management (Taylor, 1911), but had come to reject the analogy of the worker as a machine. Blackburn (1998), a lecturer in history, has provided a detailed account of the rise of industrial psychology in Australia in the period immediately following World War I, until the Depression era. He noted that Muscio focused on the then drive for ‘industrial efficiency’ in Australia, and founded the Australasian Journal of Psychology and Philosophy. This journal promoted ‘using industrial psychology to promote efficiency’(p. 122).

The earliest formal structure for IWOP in Australia was probably the Australian Institute of Industrial Psychology, established in 1927 in Sydney by A.H. Martin (Clark, 1958; Hesketh et al., 2018). It appeared to be modelled on the UK’s National Institute of Industrial Psychology (which suspended its operations in August 1973 and finally closed in 1977). This genesis reflects the strong influence the UK (and subsequently the USA) has had on the development of psychology in Australia. Until 1965, the APS was a Branch of the British Psychological Society (BPS).

World War II acted as a catalyst for progress in applied psychology in fields such as selection and assessment, training, human factors (or ergonomics), and career planning (Hesketh et al., 2018). However, it wasn’t until more recent decades that there was substantial growth in the field of IWO psychology. Commencing in Melbourne and Sydney, management consultancies started providing IWOP services from the postwar years (Young, 1977) – particularly from the late 1950s onwards. However, Hesketh et al. (2018) attributes much of the growth in IWOP to the reciprocity between Australian and overseas research units, and the cross-fertilisation of the knowledge and skills which subsequently flowed through to students studying IWOP in universities. Historically, psychology has differentiated itself from other professions such as law through its strong university and scholar base (O’Gorman, 2007), although this distinction is not as clear in more recent times.

While psychology has not always been at the forefront of changes in society, during COVID -19 there has been much greater emphasis on psychological matters. However, this attention has typically been focused on mental health issues, rather than broader behavioural and social science implications. A major activity near the end of this chapter invites students to explore how pandemics may be better managed by decision-makers making more informed use of IWO psychology and related fields.

Through this brief review of the developments associated with IWOP in Australia, it’s possible to see that multiple factors influenced the growth of IWOP. The early trend for IWOP to develop in tandem with international trends seems to continue and may even be accelerating. Nevertheless, there’s one historical element we believe requires closer attention.

The Role of Fred Emery in Shaping IWOP in Australia

Fred Emery – regarded as one of Australia’s greatest social scientists – secured a significant reputation globally for his work on socio-technical systems (STS) and semi-autonomous work groups (e.g., Emery & Trist, 1965). Emery (1969; 1981) was a pioneer in applying behavioural and systems perspectives to the emerging field of organisation development, and he was the inaugural recipient of the APS COP Elton Mayo Award in 1988. Elton Mayo was another famous Australian psychologist and was associated with the classic Hawthorne studies (see Muldoon, 2012). The British Library provides a nice summary of Mayo’s life and these studies. Hesketh et al. (2018), in citing O’Driscoll (2007), speculated that Emery’s ideas may well account for the relatively large focus on teams and groups in Australian IWOP Conferences. These events – launched in Sydney by Beryl Hesketh in 1995 – have typically featured the most prominent international IWO psychologists and contributed to the growth of IWO psychology in Australia.

Pasmore, Winby, Mohrman and Vanasse (2019) observed that socio-technical thinking (STS) is likely to re-emerge given the advancement in new technologies (see Self-Reflection Exercise 10.1). The rapid rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning is likely to pose challenges unforeseen even just a few years ago. Further, the emergence of the global pandemic subsequent to the release of their 2019 article is likely to provide further support for refinement in STS theory and its application given the global disruption and the impact at all levels of society.

Socio-Technical Systems Design (Self-Reflection Exercise 10.1)

STS emerged as a means of addressing issues in the British coal industry.

- Access the following article:

Pasmore et al. (2019). Reflections: Sociotechnical systems design and organization change. Journal of Change Management, 19(2), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2018.1553761

- Look at Table 1. and the classic STS design principles – do these still apply now more than 65 years later?

- What about the STS design for the future (pp. 77–79)?

- Does the O*NET OnLine platform and content need to be updated to reflect significant technological change over recent years?

- Do you think the design and conduct of the STAR Lab is appropriate?

- Look at Figure 3. on p. 78 and note the design elements and the three levels of outcomes. This mirrors the tripod on which stands IWOP: 3 levels of analysis in terms of individual, group and organisation, but is extended to societal considerations.

Finally, consider Career Story: Making Work Better Through Evidence and Practice later in this chapter.

Is IWOP a Friend or Foe to the Employee?

Carey (1976) provided a critical perspective on how industrial psychology and sociology have misused the evidence from a range of studies, including the Hawthorne studies. He stated that ‘Mayo and the Hawthorne researchers had been frankly paternalistic toward workers’ (Carey, 1976, p. 233). He also challenged the work of Herzberg and his model which downplayed the importance of pay as a motivator for employees. However, Carey is not the only person to have questioned the Hawthorne studies, or the interpretation of the data. Highhouse (2021) – a US scholar critical of the use of intuition at the expense of objectivity in decision-making – revisited what is known as the ‘Hawthorne Effect‘. In explaining the enhanced productivity of the workers in the original study, Highhouse offered alternative possibilities involving human relations and group dynamics, or even being observed as a research participant.

Zickar (2004) analysed the apparent indifference towards labour unions by IWO psychologists in the USA. In doing so, he investigated the history of sociology and economics, and concluded that the neglect of labour union issues by psychologists may be attributed to the lack of early, ‘pro-union’ psychologists, and a hesitancy in appreciating the existence of conflict between employers and employees. He also noted that his analysis would be enhanced by reference to research and trends outside of the USA. Kevin Murphy, a former editor of the Journal of Applied Psychology, acknowledged the increasing focus of IWO psychology on work-family relationships, but was still concerned by the narrow focus on the concerns of managers and shareholders, rather than utilising ‘a broader set of perspectives’ (Murphy, 2007, p. 22).

Perhaps a more positive picture is emerging in recent times. In a keynote address delivered during the 28th International Congress of Applied Psychology in Paris in 2014, Emeritus Professor of Organizational Psychology and Human Resource Management at King’s Business School David Guest presented a perspective which supported the view that contemporary human resource practices have enhanced both organisational performance and employee wellbeing. He concluded by noting that human resource management had provided a great opportunity for IWO psychologists to have a positive influence on policy and practice in the workplace. Nevertheless, in response to an article in the European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Guest and Grote (2018) remarked that they were concerned about undue emphasis being placed on individual agency in recent IWOP research. They argued for the need to, for example, look beyond analysis of the individual and focus more on job and organisational design for a diverse workforce. And, in another acknowledgment of the need to look beyond one’s immediate boundaries, they emphasised the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and how this could connect ‘organisational measures with regional, national and international approaches’ (p. 555).

Highhouse and Schmitt (2013) provide another perspective on the discipline of IWOP. They identified the discontent that has been percolating in SIOP for many years, particularly with the somewhat outdated name ‘industrial – organizational psychology’. They then proceed to comment on the various tensions that appear to exist in the field, namely: ‘I’ versus ‘O’, psychology (departments) versus business (schools), and science versus practice. However, these two ‘I’-oriented psychologists observed that tensions are not always bad, referencing Lewin (1951, p. 3) in noting that tension may be required for positive change. Nevertheless, the potential for tension between subgroups in work settings (for example, between management and employees), and the associated impact on IWO psychologists, reinforces the need for clear ethical guidelines. This is discussed in the next section.

Ethical Practice: a key competence in IWOP

In a session at the 28th International Congress of Applied Psychology in Paris in 2014, the incoming president of the IAAP, Janel Gauthier (Canada), remarked that the only element the various sub-disciplines of psychology across nations globally had in common was ethical behaviour. This information and discussion session was part of a lengthy project under the guidance of Sverre Nielsen (Norway), culminating in the International Declaration on Core Competences in Professional Psychology (2016). This document has been adopted by the two main international professional psychology bodies: IAAP, and the International Union of Psychological Sciences (IUPsyS). It has also been adopted by many national societies, including the APS. The Work Group – including two psychology professionals from New Zealand/Aotearoa – behind this important project continues its efforts, and an international conference is being planned for July 2022 in Slovenia. Representations and presentations from a broad cross-section of psychology sub-disciplines, and countries, are likely.

Key ethics resources for psychology students (and all psychologists) include the APS Code of Ethics (2007) and ancillary documents such as practice guides which provide valuable information and guidance even for experienced practitioners and scholars. As of April 2022, the Psychology Board of Australia (PsyBA) is developing a Code of Conduct to replace the current use of the 2007 APS Code of Ethics (AHPRA, 2020). In addition, the reader is encouraged to consult Chapter 4 of this publication. However, ethical practice should not be viewed as a self-contained segment within a course on psychology. Instead, it should permeate everything that we do.

In the area of IWOP, students, practitioners, and even scholars, can gain great value from The Ethical Practice of Psychology in Organizations (2006), edited by Rodney Lowman. Although it’s aimed at IWO psychologists in the USA, Lowman’s case study approach provides explicit guidance on how ethical principles can be applied in different settings. It’s very relevant to IWO psychologists in Australia. For example, in Case Study 10, he cited the example of a US psychologist who moved to Paris and failed to provide feedback to an individual client following an assessment centre involving psychological testing. This reluctance by the psychologist didn’t mirror the cultural norms in Europe and the UK – and for that matter, Australia. In reviewing this case against the APA Ethics Code standards, Lowman (2006) acknowledged the competence and ethical practice of the psychologist from a psychometric perspective, but this psychologist did not adapt their approach when working in a different culture.

We consider this issue further in Self-Reflection Exercise 10.2 below, which is well-suited as a group or class exercise.

Ethical Issues for IWO Psychologists (Self-Reflection Exercise 10.2)

Read Chapter 4 of this book, ‘The Essence of Ethics for Psychologists and Aspiring Psychologists’, by Tanya Machin and Charlotte Brownlow. You may also wish to dive into Allan and Love’s Ethical Practice in Psychology (2010), which provides some background on the development of the APS guidelines.

- How do these ethical principles align with Lowman?

Consider Lowman’s case studies (cited above), as well as Lowman (2018) in The SAGE handbook of industrial, work and organizational psychology: Personnel psychology and employee performance (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 39–51). http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781473914940.n3

The September 2021 issue of Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice also includes a focal article by Joel Lefkowitz on ethical dilemmas, as well as 11 subsequent commentaries.

Evidence-Based Practice and the Scientist–Practitioner Model

Gary Latham is a proud Canadian who has been actively involved in international IWO psychology for many years, particularly through IAAP’s Division 1 (Work and Organizational Psychology). Further, he has functioned as a director of the large US-based Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), with over 250,000 members. He is a co-developer of a highly influential theory of goal setting (Locke & Latham, 2002). In Latham (2019), he describes himself as a ‘practitioner-scientist’. In his 2009 book Becoming the Evidence-based Manager: Making the Science of Management Work for You, Latham demonstrated how the principles of IWO psychology can be applied by managers in organisations. One particular case study he mentioned concerned a workforce with 1,600 people which was not performing well across a number of dimensions according to the views of their employees. A new vice-president instigated a series of ‘measurable action steps’, which included:

- developing a vision statement

- conducting a job analysis (sometimes called a ‘work analysis’ or a similar name)

- selecting high performing employees based on job requirements (using structured, situational interviews)

- building behavioural appraisals based on the job analysis

- coaching employees based on the behavioural appraisals

- increasing employee motivation through goal setting.

In another section of this book, Latham expanded on the above and included commentary on job simulations, the realistic job preview (RJP), and the effective use of cognitive ability and personality tests (or ‘questionnaires’ – a term preferred by some psychologists) in personnel selection. All of the above initiatives are examples of evidence-based practice. These activities are typically grounded in solid meta-analytic evidence (mentioned briefly in the next section), with relevant research appearing in respected peer-reviewed publications.

This raises the question: To what extent do IWO psychologists operate in an evidence-based manner? British scholar Rob Briner is well known for challenging IWO practitioners to engage in practices which are substantiated by accepted evidence. Although most of his presentations and publications (including podcasts) appear to be related to evidence-based practice for management, he is also focused on evidence-based practice for the profession of IWO psychology. For example, you can watch his presentation at the BPS Division of Occupational Psychology (DOP) annual conference in Glasgow in January 2015 below (Video 10.1).

Video 10.1: Why Isn’t Organizational Psychology More Evidence-Based?

Evidence-based practice can be considered alongside what’s known as the scientist-practitioner model. There are various perspectives on this model, but it has been discussed globally over the decades.

O’Gorman (2001) outlined the history of the scientist-practitioner model and positioned the origin of this model at a conference held in Boulder, Colorado in 1949. With a focus on training programs for clinical psychologists, it appears the representatives at this conference were almost unanimous in the view that ‘the training of clinical psychologists should lay equal emphasis on research and practice’ (p. 164). It’s beyond the scope of this chapter to delve more into how the then views of science have evolved, but you can see Popper (2002) and also Chalmers (2013) for more information. O’Gorman outlined a further criticism when noting that supporters of the model in its purest form were dismissive of tacit knowledge (Eysenck, 1953; Kanfer, 1990).

Apart from identifying that practitioners rarely conduct research, O’Gorman (2001, p. 168) highlighted an underlying tension that has existed in psychology for many years – one based on observation, measurement, and experimentation (psychology’s ‘laboratory’ base), and the other ‘based on holism and humanism’. Psychology emerged out of natural philosophy, with its emphasis on observation. Grayling (2019), in the Introduction to his book The History of Philosophy, mentions the rise of science and the birth of psychology. He continues with a brief commentary on artificial intelligence, cognitive science, neuroscience, and neuropsychology, observing that contributions are continuing.

Thus, it’s perhaps no surprise that the scientist-practitioner model and evidence-based practice can be viewed and applied in different ways within disciplines, and across time and cultures.

The perceived existence of a scientist-practitioner ‘divide’ is an important issue that was alluded to earlier in the history section of this chapter when citing Zickar and Gibby (2021). This divide challenges various psychological societies (including SIOP), and this matter can emerge when designing national and international psychology conferences. How to balance the needs of scholars or researchers against the needs of practitioners? The potential for different perspectives is also evidenced in recent survey results (n = 557) of SIOP members on the topic of the rated prestige and relevance of IWOP and management journals (Highhouse, Zickar & Melick, 2020). One-third of the qualitative comments from respondents were directed towards just two classifications: ‘research – practice gap’ and ‘over – abundance of theory’. These recent representative comments (see p. 287) suggest there’s still some way to go to close the gap. Islam and Schmidt (2019) called for IWO psychologists to be less focused on theory per se, and more focused on addressing the applications of IWO psychology relevant to business practice. In essence, challenging fads and acting as ‘debunkers and testers of business practice’.

Should the scientist-practitioner model continue to be the basis of professional training in Australia, and is it an appropriate model for developing our professional competencies? In taking the views of Lapierre et al (2018) a step further, perhaps the establishment of a better-structured, coordinated, and active process for research partnerships between academics and practitioners and organisations would assist with ‘closing the gap’. This could produce valuable results for all stakeholders over time – and for IWOP. This issue is addressed in the text box on Evidence-Based Practice and the Scientist-Practitioner Model below.

Evidence-Based Practice and the Scientist-Practitioner Model

This is not an easy topic to examine, but it is important. This exercise is probably best-suited to students who have completed at least two years of undergraduate psychology studies. It’s well suited to class discussions, with the structuring of the topic not necessarily having to be on an adversarial basis.

Try to access some of the resources mentioned above, and in particular:

-

Latham, G. P. (2009). Becoming the evidence-based manager: Making the science of management work for you. Davies-Black.

- Briner (2015) (Video 10.1) (You can also Google ‘Briner AND evidence-based practice’)

-

O’Gorman, J. G. (2001). The scientist-practitioner model and its critics. Australian Psychologist, 36(2), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060108259649

-

Anderson, N., Herriot, P., & Hodgkinson, G. P. (2001). The practitioner-researcher divide in industrial, work and organizational (IWO) psychology: Where are we now, and where do we go from here? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74(4), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317901167451

Search online for other materials via SIOP, BPS Division of Occupational Psychology (DOP), and EAWOP. This should provide a range of perspectives.

- What are your thoughts regarding evidence-based practice and the scientist-practitioner model?

- Is this ‘tension’ necessarily ‘bad’? (Consider Lewin’s comments.)

- Reflect: How have you tackled this potential divide?

Scientific Enquiry and Research Methods in IWOP

We now turn to the issue of how we generate new knowledge in IWOP. First of all, consider this question: Is your work experience a good predictor of your future job performance? Most people would say ‘yes’, and the more years the better. However, this isn’t supported by the meta-analytic evidence (e.g., Van Iddekinge, Arnold, Frieder & Roth, 2019). These authors found that typical measures of pre-hire experience are, statistically, poor predictors of future job performance and turnover. Accordingly, hiring managers are strongly encouraged to use alternative or additional measures when making personnel selection decisions. This is a practical example of the importance of research. Please refer to Chapter 3 of this book for more about the research process.

Earlier material in this chapter described how psychology emerged from natural philosophy, and with it, an emphasis on observation and measurement. Taking this further, Austin, Scherbaum, and Mahlman (2002) outline the history of research methods in IWOP. Although their entry could be critiqued for being too focused on the USA, and the publication of articles appearing in the Journal of Applied Psychology, it nevertheless provides an insight into the changes and increasing sophistication of the methods used across three key domains – namely, measurement, design, and analysis. In discussing a century of progress in the field of IWOP, Salas et al. (2017) reinforced the centrality of these three components to the field.

These developments have been enhanced greatly by advances in technology and computing power, and more recently through artificial intelligence and machine learning. New fields or terms have emerged, such as ‘computational psychometrics’ (von Davier, Deononic, Yudelson, Polyak & Woo, 2019). Advances in statistical techniques include the alignment method (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014), which can assist in streamlining the process of revealing differences between large groups – including countries – on constructs of interest such as personal values.

Stone-Romero (2011, p. 39) identified three general purposes for conducting research. The following list represents a slight adaptation of his material:

- to assess relationships between (and among) unobservable constructs using manipulations or measures of variables that serve to operationally define the constructs – for example, establishing the relationship between general cognitive ability and job performance

- to determine the effects of various types of manipulations of unobservable constructs on criterion constructs – for example, the impact of RJPs on subsequent employee turnover (recall, Latham (2009) discussed the RJP in his evidence-based manager book)

- to determine whether causal or non-causal relationships between (and among) variables that are found in a study with a given set of units, treatments and observations generalise across other types of units, treatments and observations – for example, is a stress reduction intervention as effective for police officers in a child protection police unit as it is for surgeons in a trauma centre?

The claims of scientific enquiry can only be established when there is confirming evidence using new data. That is, the findings of the original study can be replicated. Nosek and Errington (2019), in examining the social and behavioural sciences, stated that across six replication efforts, only 47 per cent of the 190 claims replicated successfully. In 2020, SIOP established a Replication Task Force, with the brief to consider the establishment of an online publication devoted to publishing replications. Putting aside whether the replication is a direct or conceptual replication, it’s evident that this is an issue, particularly within social psychology:

The replication of findings is one of the defining hallmarks of science. Scientists must be able to replicate the results of studies or their findings do not become part of scientific knowledge. Replication protects against false positives (seeing a result that is not really there) and also increases confidence that the result actually exists (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2020).

Where replication is in question it should not be assumed that an original study is faulty and that the latest replication attempt is better because of its modernity. Perhaps findings from the original study are not as generalisable as thought initially, but the original study was still sound. Has the data from the studies been analysed accurately, and within the bounds of the assumptions or limits underpinning the measurement model that is being used? For example, when scaling data using what is known as item response theory (IRT), with its ‘strong assumptions’ about the nature of the data being analysed, it’s important that the variable under consideration is relatively homogenous – or internally consistent. This can be problematic when using powerful IRT-based techniques – for example, to evaluate between country differences on Openness (to experience), one of the dimensions in the widely accepted Five Factor Model (FFM) of personality.

On a related theme, Ioannidis, Salholz-Hillel, Boyack and Baas (2021) published an article which included over 200,000 publications in their analysis of COVID-19-related papers. Of the top fifteen sub-fields with the highest rates of authors, there are zero entries from the behavioural or social sciences. Although Ionnadis et al. (2021) generally welcomed the proliferation of published articles, they did offer clear warnings in terms of:

- ‘…the consistent finding of the high prevalence of low-quality studies across very different types of study designs suggests that a large portion (perhaps even the large majority) of the immense and rapidly growing COVID-19 literature may be of low quality’ (p. 11)

- ‘Such fundamentally flawed research may then even pass peer-review, since the same people populate also the ranks of peer-reviewers. Flaws go beyond retractions, which account for less than 0.1% of published COVID-19 work’ (pp. 11–12).

It appears concerns over false claims in social media about COVID-19 are not necessarily dispelled when consulting ‘scientific’ papers produced during a period of rampant publishing.

Putting this massive – and at times hurried – influx of studies to the side, scholars and practitioners can usually gain increased surety by making effective use of meta-analytic findings. Oh (2020), in citing Schmidt and Hunter (2015), describes the primary purpose of meta-analysis, a technique which is fundamental in much of modern research in psychology. With this analytical technique, existing research findings from primary studies can be quantitatively evaluated by reviewing correlation coefficients or other bivariate effect sizes. The opening paragraph of this 2020 publication took this further with the secondary use of meta-analytic data (SUMAD), citing Schmidt and Hunter’s (1998) classic review paper which curated, summarised, and tabulated eighty-five years of meta-analytic research findings on the validity (both operational and incremental) of many selection procedures. All researchers, students, and practitioners with an interest in personnel selection should be aware of this 1998 study and an important update by Schmidt et al. (2016)[2]. The study cited above (van Iddekinge et al., 2019) was based on a meta-analysis involving 44 independent samples with combined case numbers (N) of nearly 12,000.

Validity and reliability are essential concepts in quantitative research – and subsequent practice – in IWO psychology. For a useful summary of the concept of validity, and the process of validation, see Sackett, Putka and McCloy (2012) in The Oxford Handbook of Personnel Assessment and Selection, edited by the prolific Neal Schmitt, an early mentor of many current top tier scholars.

The above discussion is focussed on quantitative methods. However qualitative methods also are used in IWO research, particularly within business and management schools. Pratt and Bonaccio (2016) provided data indicating that 18 per cent of articles in the highly-regarded Academy of Management Journal contained studies that involved qualitative methods, at least in part. On the other hand, APA’s Journal of Applied Psychology published less than 1 per cent of such articles, reflecting its strong focus on research with a deductive approach encapsulating theory and empiricism (see Spector et al., 2014, discussed later in this section). Administrative Science Quarterly and Organization Science both had solid representation (over 20 per cent) of studies with a qualitative element.

Qualitative methods are an important part of psychology. Locke and Golden-Biddell (2002) presented a useful matrix comparing the modernist, interpretivist, and postmodernist paradigms. It’s not practical to discuss the history and philosophy of qualitative research here, but the following three qualitative methods, drawn in main part from Locke and Golden-Biddle (2002), are relevant:

- Action Research – This grew out of Kurt Lewin’s (1951) field theory and the conceptualisation of planned organisational change. The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations (TIHR) is a good source of examples of Action Research.

- Ethnography – Informed by cultural theory, ethnographists can take a very personalised approach, using participant observation and unstructured interviewing as the prime data gathering techniques. Archival documents and various records can also be used, with technology and computer-aided interpretive textual analysis greatly assisting in recent years. One of the criticisms of the personalised approach is how the presence of an observer may change the fundamental dynamics of a situation. A ‘hidden’ observer raises clear ethical concerns, however. Margaret Mead’s (1928) Coming of Age in Samoa is a prime example of the ethnographic approach. Despite being strong supporters of applied measurement theory and empirical approaches, Zickar and Carter (2010) advocated a ‘reconnection with the spirit of ethnography’ in organisational research.

- Grounded Theory – With its association with sociology, grounded theory is very much involved with the study of life at work. Instead of developing theories prior to data gathering, known as ‘a priori’ theorising, models or theories are generated using an inductive process. From the ‘ground up’, in effect. Locke and Golden-Biddell (2002) cited a well-known grounded theory study aimed at exploring perceptions and interactions involving medical staff, dying patients, and families within a hospital setting.

It shouldn’t be assumed that inductive research precludes the use of quantitative or empirical methods – in fact, it can be quite data–driven. Spector et al. (2014) highlighted the shift from exploratory and empirical approaches to one which can be called ‘deductive theory-based hypothesis confirmation’. In this special inductive research issue of the Journal of Business Psychology, Spector et al. (2014, p. 499) noted that ‘the field needs more inductive research to serve as the basis for theory’. These five highly regarded authors expressed a desire to see the pendulum swing back from the undue focus on deductive approaches – with a priori theorising – to a position where exploratory approaches are once again employed. In doing so, the development of new theories or models is likely to be advanced, and with it an enhanced understanding of behavioural phenomena. However, the focal article by Pratt and Bonaccio (2016) painted a picture of little change, with still limited qualitative research appearing in the top IWO psychology journals.

Other qualitative methods are discussed in Gephart (2013) and Wilhelmy and Kohler (2021). In a special issue of the European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology (December 2000), the repertory grid technique is featured – a moderately popular methodology used in the UK. Based on the personal construct theory of Kelly (1955), one of this chapter’s authors (Peter Macqueen) has used this technique to supplement psychometric and standard interview approaches in vocational and career assessment. This 2000 publication also contained an article describing a semi-structured co-research model, with the two authors affiliated with either a local government centre or a business school (Hartley & Benington, 2000).

Generational Differences and Cross-Sectional Design

- Before reading the reference below, discuss in small groups whether you think there are differences in values between the generations: Baby Boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, and Gen Z. Discuss whether you think there are/are not differences, and why.

- Putting on your IWOP hat, how would you go about evaluating the nature and extent of possible differences?

- What are some of the issues you would need to consider in conducting this research?

- Now, read the following chapter:

Gentile, B., Wood, L. A., Twenge, J. M., Hoffman, B. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2015). The problem of generational change: Why cross-sectional designs are inadequate for investigating generational differences. In C. E. Lance & R. J. Vandenberg (Eds.), More statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in organizational and social sciences (pp. 100–111). Routledge.

- Does this change your views? Do you need to consult the literature further? Does it change your approach to drawing conclusions which are based primarily on personal experience? Is terminology also an issue here?

- Engaging in a potential research project? Third- and fourth-year students, and postgraduates, are encouraged to consult not only the above book by Lance & Vandenberg, but also their original 2009 publication, Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends.

Educational Requirements for IWO Psychologists: necessary? and sufficient?

Hesketh et al. (2018) concluded their chapter with a discussion of matters pertinent to the education and registration of psychologists who have pursued postgraduate training in their niche field, known as an Area of Practice Endorsement (AoPE) for registration purposes via the PsyBA. In Australia, there are currently nine such AoPEs, including organisational psychology, whereas there are only four vocational Scopes of Practice in New Zealand/Aotearoa: clinical, counselling, educational, and more recently, neuropsychology.

Hesketh et al. (2018) make a strong case for students to look beyond the core subjects as stipulated by the body which controls educational standards for psychology in Australia, the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC). It’s appointed as an external accreditation entity for the psychology profession in Australia under the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009. On the APAC website, you can click on the ‘Students’ tab, then go down to ‘Pathways to registration’ to view a schematic illustrating the different pathway options. A great deal of other information is available on this website, including a listing of the current accreditation status of educational providers of psychology programs in Australia. Hesketh et al. (2018), and the chapter you’re currently reading, bring to light the changing scene in Australia. The profession is becoming much more health-oriented in this country, but this may also be a global phenomenon according to senior IWO psychologists overseas. However, it’s our understanding that other jurisdictions such as New Zealand/Aotearoa and the UK have less onerous or restrictive systems, while still providing adequate protection for the public. We agree with Hesketh et al. (2018) that this argument needs to be advanced.

It’s beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss the European educational system for psychologists. However, Lunt, Peiró, Poortinga and Roe (2015, Appendix 5, p. 213) outline the development and requirements of the European Certificate in Psychology – commonly referred to as the ‘EuroPsy’ – which is aimed at least at a bachelor level. Apart from the usual array of course content in the domain of ‘knowledge’, the EuroPsy framework for first phase, as it is known, includes (knowledge of) non-psychology theories from epistemology, philosophy, sociology, and anthropology.

Our conclusion provides a recommendation for Australian psychology undergraduates to study at least some of these subjects.

The standard of psychological science training in Australia is well-regarded. Nevertheless, we recommend you consider the following:

- Where do you want to channel your talents? What are your interests, and even values?

- Is it important for you to call yourself a ‘psychologist’, or become an endorsed ‘organisational psychologist’?

- Plan to enrich your educational experience by pursuing non-psychology subjects.

- Secure some relevant work experience to assist your decision-making.

- Discuss your thoughts with a range of people, including those in quality business schools. But keep in mind that that some (endorsed) psychologists, after much effort and some early sacrifices, may be vulnerable to a cognitive bias related to the ‘sunk cost fallacy’ (Thaler, 1980; Kahneman, 2011).

For most professionals, postgraduate qualifications will be increasingly expected, and this trend is likely to continue. This is something to keep in mind, although it doesn’t mean you need to pursue the six years of fulltime equivalent study as a psychology student, followed by a period being supervised as a provisional registrant, unless you want to be eligible to be registered and have the endorsed area of practice of ‘organisational psychologist’. Alternative postgraduate pathways may be available, as outlined by Hesketh et al. (2018), although this is likely to compromise your ability to use the title of ‘psychologist’ or ‘organisational psychologist’.

But some employers can place more weight on the qualities of the psychology trained applicant rather than their qualifications or registration status.

For example: A leading psychology student at a top-tier Australian university moved to Sydney after completing his fourth year of studies just a few years ago. Now in his late twenties, he is a senior analyst in London, working with an information technology and services company with over 2,000 employees. During his undergraduate studies he had demonstrated outstanding academic ability as well as initiative, entrepreneurship, and good interpersonal skills. The Sydney consultancy recognised his talents and potential, even though he had completed only four years of university education.

The Richness of IWOP including Australian examples

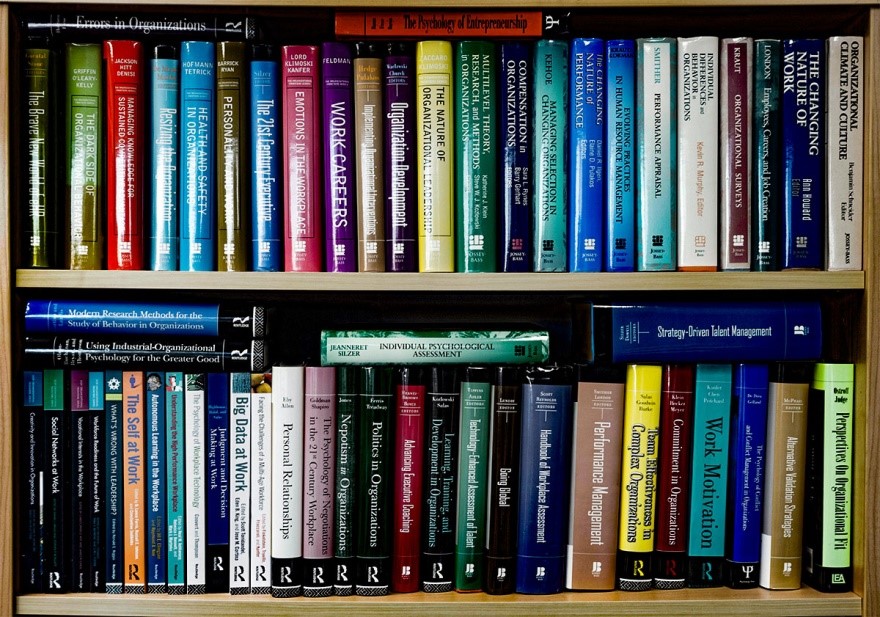

Given that IWO psychology addresses issues at the individual, group and organisational levels – and even at a societal level – it’s no surprise that this is reflected in the vast array of publications available to those interested in IWO psychology. SIOP has been prolific in its publication efforts, particularly with respect to a range of books published via Jossey-Bass and Routledge. In Figure 10.1 below, 56 SIOP books are displayed on bookshelf, from Organizational Climate and Culture (1990) in the top right, through to Social Networks at Work (2020) in the bottom left. We recommend that all students start a similar library and build their collection of resources across their career.

Look closely at Figure 10.1 – you’ll notice an extensive array of topics, with books from more recent years reflecting the increasing importance and impact of big data and technology. All books are edited, with chapters from various authors addressing different but related themes, and perhaps adopting different approaches or methodologies.

Look at topics which may be considered non-traditional. These topics are revealed in titles such as The Psychology of Entrepreneurship (2007), Errors in Organizations (2011), and more recently, Using Industrial/Organizational Psychology for the Greater Good: Helping Those Who Help Others (2013).

In Using Industrial/Organizational Psychology for the Greater Good, there’s a chapter co-authored by Michael Frese, a former president of IAAP. He’s a also co-editor of the other two books mentioned, and is a good example of an IWOP scholar who has worked successfully at various levels with organisations and across countries. With joint appointments from Singapore and Germany, he has researched matters such as personal initiative, training, and learning from errors and experiences. In particular he has focussed on the development of entrepreneurship and poverty reduction programs in emerging economies, taking a scientist-practitioner perspective and an action theory approach.

In Using Industrial/Organizational Psychology for the Greater Good, there is a chapter co-authored by Stuart Carr, Professor of Psychology at Massey University, Aotearoa/New Zealand, globally renowned for his use of IWOP for humanitarian purposes. Another chapter is co-authored by Michael Gielnik and Michael Frese, addressing entrepreneurship and poverty reduction, and the application of IWO psychology in developing countries. Back in Australia, there is the work of Charmine Härtel. As part of her inclusive entrepreneurship program, Härtel recently released some fascinating and relevant findings in the fourth most influential journal in the field of management, the Journal of Business Venturing. This study (Mafico, Krzeminska, Härtel, & Keller, 2021) – conducted with one of her PhD students and his other supervisors – has shown how different intellectual experiences of migrants show up in the way they organise their enterprises. For example, immigrants who had early experiences of inclusion tended to balance social and commercial goals and staff enterprises with individuals from their host and heritage cultures. In contrast, immigrants who had early experiences of exclusion tended to focus on social goals directed at their heritage country and to staff their enterprises with individuals from their heritage culture. It also found that the cultural gender expectations immigrant women grew up with influenced the degree to which they pursued social and gender normative organisational goals. Härtel and her colleagues are now seeking to leverage their findings to help migrants successfully start up and run businesses.

Stories From Australian IWO Psychologists

The section above highlights some of Härtel’s recent work, with implications for migrants and business. The following reveals some of her background and professional journey, as well as that of seven other Australian IWO psychologists: four practitioners and four scholars in total (represented in Figure 10.2), although at times the lines are blurred.

Brisbane

Career Story: Emotions at Work

Neal M. Ashkanasy OAM, PhD

My journey began many years ago when I first set eyes on a construction site. I knew then that my career would be in civil engineering. I loved maths and science at school and could not wait to begin my chosen career. I studied at Monash University because it was a new and exciting institution at the time, and I was not disappointed. My major interest was in water resources engineering, so upon graduation in 1966, I enrolled in the water engineering master’s program at the University of New South Wales, and soon had a job with the Queensland State Water Authority. My first job, however, was not what I expected. I was given a crew of 180 men (yes, all men in those days) and told to go out into the bush and build a town to accommodate 1,500 workers and their families![1] That was how I first learnt that the main requirement for an engineering career was not technical, but people skills.

After 18 years in my engineering career, I managed to achieve some level of success,[2] but I became concerned that engineers – while good at the technical side of their work – were paradoxically all too often failing in the (all important) people management side. To try to understand this paradox, I enrolled in the psychology program at the University of Queensland, eventually graduating with a PhD in social and organisational psychology.[3] I also made up my mind that I would move to an academic research career to study how organisational leaders could improve their performance as people managers. I soon came to realise, however, that cognitive and behavioural theories of leadership failed to explain organisational leaders’ performance failings, and that this was because leadership researchers had ignored the importance of emotions in leadership and decision-making. After coming to that realisation, I decided to devote my research career to studying the role emotions play in organisations and especially in organisational leadership. Over my 35-year career as an organisational psychology researcher, I have managed to publish over 750 books and scientific papers. I like to believe that I have accomplished at least a little of what I set out to do, and that my work has been recognised by my peers, including the 2011 Elton Mayo Award for Distinguished Research and Teaching.[4] I am especially proud that my work has helped organisational leaders to understand that improving their emotional intelligence is an essential key to success.

References

Ashkanasy, N. M., & Dorris, A. D. (2017). Emotions in the workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113231

[1] The town was the construction township for Fairbairn Dam, located near Emerald in Queensland’s Central Highlands.

[2] Chair of the Institution of Engineers’ National Committee on Hydrology and Water Resources.

[3] My thesis topic was Supervisors’ responses to subordinate performance.

Career Story: Behavioural Economics

Phil Slade, Co-Founder of Decida

Following a relatively successful professional career in the arts as a composer for film and theatre, I transitioned to psychology in my early thirties. I was always curious about how music, sound, lighting, and story-telling influence people’s emotions and perceptions, and figured that this was a natural step in pursuing that curiosity. The role that emotion, cognitive bias, and awareness has on decision-making was the focus of my thesis during my Master of Organisational Psychology program, and I have never looked back since.

Working in the field of judgement and decision-making means my organisational psychological journey has had to cover areas such as emotion, behavioural economics, individual differences, social psychology, politics, and traditional economics. There are many fantastic books that can help you to start exploring this space, and my top recommendations appear bellow.

This mix of expertise has led to working with a raft of major institutions (most notably Westpac, NAB, Suncorp, Queensland Health, SunSuper, ASIC, APRA, The World Bank, Queensland Treasury, and the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority) to help assess and develop products and services that lead to better financial decision for customers.

My work is mostly a combination of presentations to boards and executive leadership teams, leadership and emotional intelligence workshops, developing and delivering ethical assessments of financial products and services, coaching for influential decision-makers, overseeing and helping deliver large scale change and innovation initiatives, and playing the role of lead negotiator in sensitive negotiations.

This work has also graciously led to many opportunities to write and publish. This has included two books –Behavioural Economics for Business (2016) and Going Ape S#!t (2020) – a regular column for Money Magazine, many podcast interviews, and being a regular commentator in the media generally regarding the psychology of financial decision-making and emotional reactivity. This part of my work is particularly satisfying because I believe it helps demystify key psychological concepts and helps make our society better decision-makers collectively and individually.

Through our work with digital innovation and transformation, we were able to develop products (both digital and physical products) that improve mental health and emotional intelligence. This has led to experimentation with artificial intelligence, big data, digital user experiences, and wearable tech applications. One of the most exciting developments is a check in and emotional ‘switch’ app that is being used in schools and workplaces to track and improve mental health and wellbeing and increase emotional intelligence. Bridging the gap between psychological insights and embedded behaviour change is immensely satisfying, and it all started with organisational psychology.

Recommended Reading

- Thinking Fast and Slow (Daniel Kahneman, 2001)

- Going Ape S#!t (Phil Slade, 2020)

- Looking For Spinoza (Antonio Domasio, 2003)

- Freakonomics (Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner, 2005)

- The Ethics of Influence (Cass Sunstein, 2016)

Dr Doug MacKie, CSA Consulting

In my final year as an undergraduate studying psychology (in the UK), we got the opportunity to learn about the applied domains from practitioners in the field. Clinical appealed to me as I came from a medical family so the territory was familiar, and it offered significant job security due to the high barriers of entry and almost unlimited demand. Being accepted into the postgraduate training program in clinical psychology was highly competitive and required experience which I obtained as a research assistant on a project on the neuropsychology of Alzheimer’s disease. I was fortunate to be successful with my first application and completed the two-year Master of Science (MSc) at Manchester University in the UK. What really engaged me about the course was the applied component – we would literally be taught a subject one day and be applying it in a clinical setting the next.

There was no shortage of jobs available on graduation so I took the opportunity to travel for a year and undertook a locum in a psychiatric hospital in Brisbane as part of my trip. On return to the UK, I specialised in adult mental health and general medicine and moved relatively quickly up the career structure within the public sector in the UK. I was several years into my clinical career before I felt the dissatisfaction creeping in. Clinical training had provided a rarefied and protected environment in which to practice, but full-time work exposed me to the politics and turf wars that had been largely hidden. This combined with the limited vision of success – clients were discharged on symptom remission which to me seemed like the time to increase engagement, not remove it. Positive psychology held a strong ideological and increasing empirical pull for me, and organisational psychology offered the opportunity to work with those already high functioning to see if I could add value in that setting. The final issue that completed my disillusionment with the clinical pathway was the realisation that the over-reliance on clinical skills had not prepared me in any way for the organisational, political, and leadership demands of senior clinical roles. Levelised leadership had been completely overlooked in clinical training.

After retraining in organisational psychology, and enduring the obligatory time in a consultancy practice, I opened my own business in Brisbane. The erratic income and uncertainty of business development was more than compensated for by the autonomy and sense of personal responsibility that comes from both designing and delivering a bespoke solution to the client’s needs. It took me a while to realise the importance of purpose in my work, and helping organisations flourish and deal responsibly with the emerging climate crisis has sustained me for the last twenty years. Coming from an academic family, research has always played a significant role in my work. Driven by a desire to enhance the evidence-base in workplace and leadership coaching, I initiated a doctorate in strength-based leadership, really sharpening my appreciation of the literature and credibility in the field.

When I first considered my transition from clinical to organisational psychology (to which I have added health and coaching along the way), a number of senior organisational practitioners advised me against it, telling me that it was destined to fail. This was poor advice. There is significant variety within the domain of applied psychology and transitions are easier than you think. Modular training programs and specialist titles and registrations tend to emphasise the differences rather than similarities in the various areas of applied psychology. Taking a step back and down in terms of experience and expertise was challenging but ultimately worth it.

My final advice is to really reflect on and understand the costs and benefits of different employment models and match them to your career stage. Very few individuals have the business acumen to go immediately from university into private practice. Most will want and need to hone and develop their skills in the context of a supportive and nurturing environment that provides the essentials like access to clients and peer support. Do not underestimate the value of these opportunities in your own development. I am convinced that my own experience within the clinical domain – that gave me insights into the public sector as well as a deep and profound insight into human motivation, resistance to change, behavioural and cognition models of mood, cognitive bias, and human development – has made me a far more effective practitioner that would otherwise be the case. As I consider my next transition to environmental and climate change psychology, the confidence acquired in previous domains undoubtedly underpins the optimism I feel that it will be a successful and engaging one.

Sydney

Career Story: Human Factors and Safety

Allison McDonald, Managing Director, SystemiQ

Human Factors is a multidisciplinary field, drawing upon a range of professional disciplines such as psychology, biomechanics, anthropometrics, and systems engineering. It is an exciting and rewarding career pathway, closely linked with both organisational psychology and cognitive psychology. I first encountered the field of human factors when working on a project with a mining research organisation for my Master of Organisational of Psychology thesis. I immediately enjoyed the applied research focus, and the opportunity to work with people and technology in complex and fascinating industries. Since then, my human factors specialisation has enabled me to work at an operational and strategic level with organisations such as Queensland Rail and Qantas in Australia, and Etihad Airways in the Middle East. It has also more recently provided incredible opportunities to travel and work with many different airlines across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East in a consulting role.

Human factors applies an understanding of the human sciences – including psychology – to optimise the design and operation of systems. It uses structured methods to understand the way in which people interact with equipment, their surroundings, information, and other elements of systems to perform their tasks. This understanding of human-system interaction is used to help designers to consider the needs, abilities, and limitations of people who will use the systems. The integration of human factors in design (often referred to as ‘human-centred design’) aims to make systems safe, effective, and comfortable for human use.

Human factors professionals work in a wide range of contexts, from the design of products and built environments that we use in everyday life, to the design and operation of complex high-reliability systems in industries such as aviation, rail, health care, energy, or process industries. Human factors involves working closely with the people who perform safety-critical work in these complex systems and environments to understand their tasks and the context in which the tasks are performed.

In addition to being involved in design processes, human factors professionals may work in operational settings focused on safety management. In this context, they help organisations to understand the factors that affect human performance – both in understanding what keeps operations safe and effective, and in identifying the factors contributing to incidents and adverse outcomes. Integrating human factors into safety and risk management contributes to safer outcomes by identifying improvements required to equipment, procedures, job design, training, and other performance-shaping factors within the organisational system.

Human factors is a growing field of practice, and as technology continues to advance rapidly, the focus on how people interact with complex systems will only continue to increase in importance. Human factors is a rewarding field of work which directly contributes to systems that better support the people who interact with them.

Useful Resources:

-

Video: ‘What is human factors science?’

-

International Standards Organisation (ISO). (2019). Ergonomics of human-system interaction – Part 201: Human-centred design for interactive systems. ISO 9241-210:2019(E). Geneva: ISO.

-

Wickens, C. D., Lee, J., Liu, Y., & Gordon-Becker, S. (2014). An introduction to Human factors engineering (2nd ed). Pearson Education.

-

Wilson, J. R., & Sharples, S. (2015). Evaluation of Human Work (4th Ed.). CRC Press.

Melbourne

Charmine E. J. Härtel, Distinguished Professor of Management, Inclusive Employment and Entrepreneurship

I come from a blue-collar background, growing up first on isolated islands and a native community in Alaska, and later a small country town in Montana. My early experiences were of a collectivist society where I was a valued child of the community and oblivious to notions of race or exclusion, i.e., I did not know I was white nor did it affect my belongingness. When I left that small Alaskan community, I ventured to parts of the world where I was confronted with acts of racism and exclusion. It was bewildering to me to see how unkind people could be when I knew from the community of my childhood how embracing of diversity humans could be. This fuelled in me a strong desire to do work that encouraged the best of humanity to shine through. I decided to do this through obtaining a PhD in I/O psychology after vocational interest inventories I took revealed to me my interest in research and science, and that pursuing a PhD would be a good path for me to achieve meaningful work for myself. I/O psychology provided the ideal grounding to pursue my passion for supporting the employment and entrepreneurship of disadvantaged groups, as it coupled a deep scientific understanding of human behaviour with rigorous methods for studying it and developing practical actionable solutions.

Fast forward to now, and I’m proud to say I am a recipient of the Australian Psychological Society’s prestigious Elton Mayo Award for scholarly excellence, a Fellow of the (U.S.) Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP), and a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia (ASSA) amongst other recognitions. The two research streams I have established have had both academic and practical impact.