6 Applications and Careers for Counsellors and Counselling Psychologists

Nathan Beel; Nancey Hoare; Michael Davies; Denis J. O’Hara; and Jan du Preez

Introduction

This chapter is based on an original chapter written by Borgen and Neault (2019) for the Canadian version of this handbook. We have rewritten and updated the chapter to reflect the Australian context and to ensure its relevance to the counselling and counselling psychology professions in Australia for those contemplating a career within these professions. Professional counselling is provided primarily by two groups in Australia: counsellors and counselling psychologists. Unlike counselling, which is linked with its own profession, counselling psychology is a specialisation within the psychology profession, and this Area of Practice Endorsement (AoPE) is undertaken after registration as a psychologist. As both counselling and counselling psychology have grown as professions, each have evolved unique identities and scope of practice. It can sometimes be confusing for students to understand the distinctions between the professions given that they are so closely related, so this chapter will focus on the Australian definitions of counselling and counselling psychology and the scope of practice in each area.

This chapter will cover the counselling and counselling psychology professions separately at first, by providing a brief history of each and describing typical training and registration requirements, research approaches, evidence of quality, and contexts in which each are practised. As we cover each of these professional fields, you will see that there are many similarities between them – as well as some differences – so after we talk about the professions separately, we will provide you with an overview of these similarities and differences. To end this chapter, we will offer some suggestions to assist you with deciding which profession would be most suited to you.

We will start off with a brief historical overview of the counselling profession, followed by an outline of current practices in the fields of counselling and psychotherapy and how these practices are evaluated. Then, we will look at some career paths for counsellors, including training options and registration. We will then explore the counselling psychology profession in Australia, starting with a brief historical overview of counselling psychology, followed by an outline of current practices in counselling psychology and how these practices are evaluated. After that, we will look at some career paths, including training options, registration as a psychologist, and an Area of Practice Endorsement (AoPE) for counselling psychologists.

The Counselling Profession

History of Counselling in Australia

The emergence of counselling associations in Australia can be traced back to the 1940s, with the commencement of the Melbourne Institute for Psychoanalysis, the National Marriage Guidance Council, and the Australian Hypnotherapists Association (Schofield, 2008). In the 1990s there were over 50 distinct professional counselling and psychotherapy associations, each with their own membership criteria and standards (Schofield, 2013).

In the contemporary landscape there are currently two peak bodies of counselling in Australia to which counsellors can apply for membership. The the Australian Counselling Association (ACA) and the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia (PACFA) were both founded and registered in the late 1990’s. The Australian Counselling Association (ACA) was established with a purpose to make counselling association membership available for individual counsellors (Armstrong, 2006). The ACA’s approach emphasised inclusivity for all counsellors, that encouraged all qualified practitioners to become registered and bound by ethics, rather than have them practicing without any form of regulation. It developed its own code of ethics, training standards, scope of practice, professional development, advocacy for greater recognition of counselling, and provided members with a range of benefits such as reduced professional indemnity insurance premiums. It is currently the largest counselling association in Australia.

The establishment of the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia (PACFA) was originally initiated by counselling academics concerned that educational deregulation might weaken the quality of counselling training (Brear & Dorrian, 2010). Its initial structure was a federation of regional and specialist counselling and psychotherapy Member Associations throughout Australia aimed at facilitating national representation for the profession. PACFA later restructured to allow individuals to gain direct membership, and subsequently several Member Associations decided to dissolve and transfer their members to become direct members of PACFA. PACFA created its own minimum training standards, a unified ethics code, scope of practice, reduced insurance premiums, and other benefits. Its key aims are to enhance the professionalisation and recognition of counselling and psychotherapy within Australia via international benchmarking and advocacy.

Defining Counselling

The historical and ongoing confusion around terminology, titles, and scope of practice in the broad field of ‘counselling’ is well documented (Beel, 2017; Hanna & Bemak, 1997; O’Hara & O’Hara, 2014). Some confusion around the term ‘counselling’ results from the fact that the common English understanding of the verb ‘to counsel’ is ‘giving professional advice’. In fact, many professionals including human resource officers, employers, lawyers, medical doctors, or schoolteachers may provide ‘counsel’, as in offering advice. Other professionals work under the title of ‘counsellor’ but with an additional descriptor – guidance counsellors, financial counsellors, career counsellors, and genetic counsellors are just a few examples. However, most counsellors and psychotherapists focus on personal issues that clients seek help with and would distance themselves from advice-giving, preferring to work alongside their clients, assisting them with finding their own solutions to their problems.

Reinforcing the broad conceptualisation of counselling within the Australian employment context, the Australian Government National Skills Commission Job Outlook site notes information provision as the foremost part of the definition of counsellors.

Counsellors provide information on vocational, relationship, social and educational difficulties and issues, and work with people to help them to identify and define their emotional issues through therapies such as cognitive behaviour therapy, interpersonal therapy, and other talking therapies (National Skills Commission, n.d.).

If counsellors distance themselves from definitions that suggest the provision of advice, how is counselling defined? Defining counselling is challenging given the diversity of practice and understanding within the profession. The Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia (PACFA), one of two peak bodies of counselling in Australia, define counselling as:

…a safe and confidential collaboration between qualified counsellors and clients to promote mental health and wellbeing, enhance self-understanding, and resolve identified concerns. Clients are active participants in the counselling process at every stage (PACFA College of Counselling, n.d.).

This definition highlights a trustworthy, ethical, and egalitarian relationship, approved academic qualifications and preparation of the counselling practitioner, and a focus on personal growth and change. The definition sets itself apart from a medical model approach, which sets up a more hierarchical relationship which emphasises scientific knowledge and therapist expertise, transposes client difficulties into disorders, utilises diagnostic assessment, and encourages client compliance with treatment recommendations. The definition does not suggest counsellors reject a medical model understanding of psychological distress and impairment, but that they tend to lean more towards egalitarian, person-centred, and relational practice.

An additional source of confusion is that the term counsellor can designate a person who delivers counselling, irrespective of their professional membership, and it can indicate a member of the counselling profession. Psychologists, social workers, human services workers and even untrained individuals may use the title ‘counsellor’, and identify it as their occupation, or job position (Beel, 2017). To reduce misunderstanding, those who are members of the counselling profession may use the terms ‘registered counsellor’ and ‘professional counsellor’ to signal their membership to and identity in the counselling profession.

A distinct though related identity to that of a counsellor is the psychotherapist. The term ‘psychotherapy’ is often used synonymously with counselling or therapy in textbooks in the United States (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013) and Australia (O’Donovan et al., 2013). In the Australian counselling context, psychotherapy is viewed as typically a lengthier process, offering deeper psychological engagement, and resulting in enhanced levels of insight and personality change. Australian psychotherapists have identified specific modalities recognised as psychotherapies, and typically undergo longer and more intensive training (College of Psychotherapy, n.d.) than counsellors. In contrast to psychotherapy, counselling is typically briefer and more focused on resolving specific problems, life adjustments, and personal wellbeing (PACFA, 2021d). There is substantial overlap in the definitions, processes, and issues that both counsellors and psychotherapists address. In addition, psychotherapists may belong to different professions than counselling, such as psychology, psychiatry, and social work. For conciseness, the usage of the term ‘counsellor’ in this chapter will refer to both counsellors and psychotherapists.

A more recent title of Aboriginal and Torres Strait practitioner or healer has been endorsed by PACFA’s College of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Practices (CATSIHP). This is a distinct term (but not mutually exclusive) from psychotherapist or counsellor, and represents support for, and recognition of traditional healing practices within the Australian and other indigenous communities (PACFA, 2020; PACFA, 2021b).

It’s also important to recognise there are other types of counsellors who are not registerable within the counselling profession unless they have completed specific bridging studies. Rehabilitation counsellors, genetic counsellors, guidance counsellors, and community counsellors are distinct professional identities, with their own unique associations: the Rehabilitation Counselling Association of Australia, Australasian Society of Genetic Counsellors, Australian Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, and the Australian Community Counselling Association.

As previously mentioned, there are currently two peak bodies of counselling in Australia to which counsellors can apply for membership: the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia (PACFA) and the Australian Counselling Association (ACA). The Australian Register of Counsellors and Psychotherapists (ARCAP) is an organisation jointly-owned and operated by both the ACA and PACFA with the purpose of publishing a common public register of Australian counsellors. Practicing members registered from either peak body are automatically placed on this register. However, it should be noted that the register distinguishes between different levels of registration reflective of the different training requirements of the two associations. Members of the public can search the register to check the registration status of a therapist, and the website also has a complaints portal for the public. In addition to providing a public register, ARCAP is used as a unified entity for the counselling profession to lobby the government.

Counsellors’ Work Settings

Counsellors work in an expanding range of settings. These include private practice, educational settings such as schools and universities, mental health and health services, correctional facilities, rehabilitation services, public agencies, employee assistance programs (EAPs), and non-government human services organisations (PACFA, 2018; Schofield & Roedel, 2012). More recent data from the Australian Government National Skills Commission’s Job Outlook website (n.d.) – which is based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) census 2016 data – broadly categorises counsellors in the following industries: Health Care and Social Assistance (47.4%), Education and Training (36%), Public Administration and Safety (4.2%), and Other (12.4%). Though counsellors are spread across various sectors, the most common practice setting for counsellors is private practice – variously estimated between 47 per cent and 63 per cent (Pelling, 2005; Schofield & Roedel, 2012) – though more than half of private practitioners also work in other work settings (Schofield, 2008).

Want to know more? The Australian Government National Skills Commission’s Job Outlook (n.d.) website page on ‘Counsellors’ provides generally updated data on counsellor ages, earnings, working hours, education levels, and outlooks. Go to the Job Outlook website and search for ‘counsellor’.

Counsellor Roles and Activities

Counsellors work with children, adolescents, and adults across the lifespan, individually, with couples, and with family and other groups, focusing on a range of issues. Counsellors support clients with careers, addictions, trauma, grief, relationships, abuse, cultural, spiritual, and adjustment issues, and learning challenges. The goals often involve clients wanting to come to a better understanding of themselves, and/or how they interact with those around them, to help them live more satisfying and productive lives. As already stated, counsellors do not become directly involved in diagnosing psychopathology. However, they do see clients who are struggling with various degrees of distress and impairment, and who seek assistance in moving forward with their lives in a positive way.

Counsellors also provide services other than counselling. They may offer clinical supervision –which is a professional mentoring role to support professional development and wellbeing of counsellors and psychotherapists – and vicariously support competent and ethical practice delivered to clients. Therapists can apply to be registered as clinical supervisors after a specified time as a registered counsellor, and the completion of clinical supervision training. The ACA and PACFA both require all practitioners receive a minimum number of hours of clinical supervision each year as part of their membership conditions.

Another function that counsellors may engage in is teaching. Counsellors will, at times, deliver information sessions to various community groups on topics related to the counsellor’s expertise. Some will deliver professional development to counsellors and other mental health practitioners both as a means of ‘giving back’ to the profession and to generate additional income. Other counsellors will be employed as counselling educators/lecturers to train the next generation of counsellors. These training roles may be sessional or on a continuing basis, and may be employed at private or public, vocational, or higher education institutions and universities. To date, there are no counsellor educator training programs in Australia to specifically prepare future faculty. However, both the ACA and PACFA have a membership category specifically for counselling educators, and there is a somewhat informal National Heads of Counselling and Psychotherapy Educators organisation that caters to the needs of directors of counsellor training in Australia.

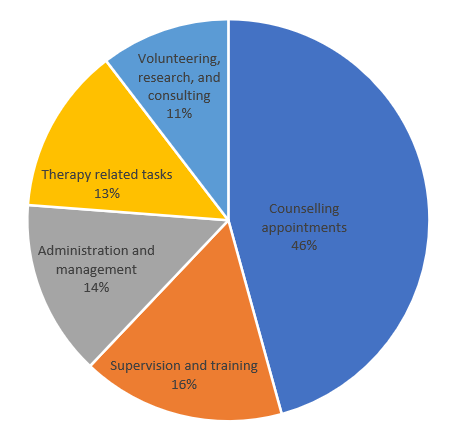

So how do Australian counsellors spend their time? In one study (Schofield, 2008), a sample of 316 counsellors spent more time on average providing counselling than any other activity. Counsellors spent 12.3 hours per week in counselling appointments, followed by 4.4 hours in supervision and training, 3.8 hours in administrative and management activities, and 3.6 hours in tasks related to therapy (e.g., writing case notes). The remainder of 2.8 hours were spent on volunteering, research, and various consulting activities. Figure 6.1 shows the same information expressed in percentages. Although this pie chart shows counsellors spend less than half of their time in counselling on average, some counsellors will spend a larger proportion of time conducting therapy, while others may primarily occupy other roles such as manager or educator, and maintain relatively few hours each week practicing therapy.

Training, Registration, and Career Paths for Counsellors

The analogy of many paths in the woods leading to the same destination is very true for counsellors. Some people pursue a straightforward path of education and work experience that strategically positions them for registration as a counsellor or psychologist. Others take a more meandering approach, with twists and turns over a lifetime of employment.

The pathway for becoming a counsellor registered with either (or both) of the two peak counselling associations starts with undertaking a training program recognised by the ACA and/or PACFA. Both accrediting bodies list, on their respective websites, the training programs they have assessed as meeting their course training standards. While applicants for membership may apply for Recognised Prior Learning (RPL) with a combination of studies and experience, the surest pathway is completing a recognised qualification. The ACA (2021) accepts a minimum of a nationally recognised diploma of counselling (CHC51015) for practicing membership, while PACFA’s (2021b) minimum is a three-year undergraduate or two-year postgraduate level degree that meets its training standards. Some practitioners can join PACFA after satisfying Recognition of Prior Learning that meets their training standards. Masters level qualifications in counselling are a popular pathway for graduates from other degrees to meet the educational requirements.

Both peak bodies have a student level of membership, which can be upgraded to Provisional Member (PACFA) or Level 1 (ACA) after graduation. PACFA’s full membership level is the Clinical Member, and is gained after meeting the supervision, time, and experience requirements. The ACA also has experience and supervision requirements to advance in the levels of membership, from Level 1 to Level 4, however to progress to Level 3 and beyond, one must have additionally completed the equivalent of a Bachelor or Master of Counselling.

Counselling is a richly practical and intensely interpersonal activity, and the training expectations reflect this. The training standards from both associations understandably emphasise that a substantial volume of training must focus on counselling theories and skill development, and encourage the student’s engagement in self-awareness and reflection. In addition, students are required to attend face-to-face classes (which may include residential schools for distance classes), and a counselling placement, both which support by implication that counselling is a relational practice that can’t be learnt solely from textbooks.

PACFA has psychotherapy training standards that are additional to the PACFA training standards (PACFA, 2020). These standards emphasise the personal development of the psychotherapy student and will require that they have logged hours of their own experience of psychotherapy, to support their professional formation (PACFA, 2020).

Both professional peak bodies have specialised colleges within their associations. PACFA has colleges for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Practices, Counselling, Counselling and Psychotherapy Educators, Psychotherapy, and Relationship Counselling. In addition, registered PACFA Counsellors can also undertake training to become a registered mental health practitioner. The ACA has colleges titled Alcohol & Other Drugs, Family Therapy, Grief & Loss, Counselling Supervisor, Christian Counsellor, Creative Arts Therapies, and Clinical Counsellors.

Pearson (2017), looking ahead to potential employment in 2030, identified counselling as one of the top 10 occupations most likely to experience increased demand. In their implications section, and reflecting an expectation of increased automation and artificial intelligence, they recommended developing ‘skills that are uniquely human’ (Pearson, 2017, p. 8). However counselling students shouldn’t take future demand as a guarantee for work on graduation, as there are currently 40 institutions in Australia teaching thousands of counselling students. Students should consider how they can enhance their employability by active networking (e.g., joining as a student member of ACA/PACFA, attending networking events, etc.), gaining relevant volunteer experience (e.g., Lifeline), attending professional development events, familiarising themselves with and learning to counsel using different technological platforms, maintaining a log of their experience and supervision, and after graduation, working towards full membership of their chosen association. In addition, students should review counselling advertisements on job sites like SEEK to see what employers are asking for, and where the hiring needs are. Depending on the availability of work in your locality and supply of competing qualified applicants, counselling graduates may need to compete for positions through strategic preparation alongside their journey of study.

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Counselling

Significant work has been done to evaluate efficacy and outcomes associated with counselling. Counselling has been shown to be a highly effective form of treatment (Smith & Glass, 1977; Wampold & Imel, 2015). Early writers have extensively examined what made counselling effective. Dr. Carl Rogers, an influential pioneer, suggested that for counselling to be effective, the counsellor must bring genuineness, empathy, and positive regard for the client (Rogers, 1961). As the professions of counselling and counselling psychology have evolved, studies focusing on the importance of the therapeutic relationship between the client and the counsellor in a confidential setting have continued to demonstrate the importance of the counsellor in making counselling interventions effective. Research continues to demonstrate that the strength of the therapeutic relationship is important in determining the effectiveness of counselling and counselling psychology interventions (Flückiger et al., 2018). Both counselling peak bodies encourage their members to monitor client progress using formal outcome measures (Australian Counselling Association, 2020; PACFA, 2018) and adjust counselling as needed.

Counselling Psychology

History of Counselling Psychology in Australia

Counselling psychology as a profession is well-established, although it can be argued that it is still in its infancy. As a specialist field, counselling psychology has been around since 1946 in the USA, with its original foundations being in vocational counselling and counselling for war veterans (Grant et al., 2008), but other countries have been slower to recognise it as a profession in its own right. For example, it wasn’t until the end of 1982 that a separate Counselling Psychology Section of the British Psychological Society (BPS) was established in the UK, and it became the BPS Division of Counselling Psychology in 1994 (Orlans & Van Scoyoc, 2009).

The Australian Psychological Society (APS) is the peak professional body for psychologists in Australia. It was established in 1944 as the Australian branch of the British Psychological Society (BPS), but in 1966, it became incorporated as the Australian Psychological Society Limited (Allied Health Professionals Australia, 2021). There are two main types of Psychologists in Australia – those with general registration and registered psychologists with an Area of Practice Endorsement (AoPE, APS, 2021df). There are currently nine endorsed areas of practice, namely:

- clinical neuropsychology

- clinical psychology

- community psychology

- counselling psychology

- educational and developmental psychology

- forensic psychology

- health psychology

- organisational psychology

- sport and exercise psychology.

An AoPE allows psychologists to use a title specific to their area of practice (e.g., ‘Counselling Psychologist’, ‘Clinical Psychologist’, ‘Organisational Psychologist’), whereas registered psychologists without an AoPE use the title ‘Psychologist’. You can see that counselling psychology is included as an endorsed area of psychological practice in Australia, but it wasn’t recognised as a distinct field until about 50 years ago, in 1976, when the Division of Counselling Psychologists was formed (Grant et al., 2008). In 1992, the name was changed to the the APS Division of Counselling Psychologists. It’s now known as the APS College of Counselling Psychologists (Davis-McCabe, et al., 2019).

La Trobe University was the first to offer training in counselling psychology in 1975 (Di Mattia & Grant, 2016) and many universities began offering specialist masters and doctoral programs in counselling psychology (Wills, 1999). However, with the advent of the Better Access initiative, introduced by the Australian Government in 2006 (Littlefield, 2017), there has been a decline in training for counselling psychology (Di Mattia & Grant, 2016). Currently, there is only one university in Australia (the University of Queensland) that offers accredited postgraduate training in counselling psychology, which is a pathway to an AoPE as a counselling psychologist (Australian Psychology Accreditation Council [APAC], 2021).

The Better Access initiative provides Medicare rebates for eligible Australians to access mental health services (Australian Government Department of Health, 2021a). It is a two-tiered rebate system, whereby tier one services are provided by clinical psychologists and attract a higher Medicare rebate, and tier two services are provided by other registered psychologists, including counselling psychologists, as well as other professionals, such as occupational therapists and social workers. Under this system, a distinction has been made between the treatment of a mental disorder by a clinical psychologist (termed ‘Psychological Therapy’) and the treatment provided by other Psychologists (termed ‘Focused Psychological Strategies’) and this has created some tension within the profession and led to substantial growth in clinical psychology training programs and endorsed clinical psychologists (Di Mattia & Grant, 2016). This is evident in the current memberships of the APS Colleges, with the College of Counselling Psychologists representing over 1,000 members (APS, 2021c) and the APS College of Clinical Psychologists representing over 6,000 members (APS, 2021b).

Defining Counselling Psychology

Like the counselling profession, counselling psychology has also struggled with ongoing confusion around terminology, titles, and scope of practice (Gazzola, 2016; Haverkamp et al., 2011; Neault et al., 2013). In part, this is not surprising, given that formal psychological counselling is a relatively new profession, beginning to establish itself as a profession in Australia in the 1970s.

Counselling psychology is part of the broader discipline of psychology, which is the scientific study of ‘…mental processes (thinking, remembering, and feeling) and behaviour’ (Burton et al., 2019). Counselling Psychologists use a strength-based approach to provide evidence-based psychotherapy in a therapeutic relationship with their clients. They provide assessment and diagnose a range of psychological issues for people across the lifespan. See the Australian Psychological Association’s (APS, 2021c) College of Counselling Psychology definition here.

Counselling psychology is concerned with using psychological principles to enhance and promote the positive growth, wellbeing, and mental health of individuals, families, groups, and the broader community. Counselling psychologists bring collaborative, developmental, multicultural, and wellness perspectives to their research and practice. They work with many types of individuals, including those experiencing distress and difficulties associated with life events and transitions, decision-making, work/career/education, family and social relationships, and mental health and physical health concerns. In addition to remediation, counselling psychologists engage in prevention, psychoeducation, and advocacy. The research and professional domain of counselling psychology overlaps with other professions such as clinical psychology, organisational psychology, and mental health counselling.

The Counselling Psychology Profession in Australia

The titles of ‘Psychologist’ and ‘Counselling Psychologist’ are protected by law. To use either of these titles and to provide psychological services to the public, a practitioner must be registered with the Psychology Board of Australia, which is part of the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). AHPRA is responsible for regulating 15 national health practitioner boards in Australia (AHPRA, 2021) under the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS) (Australian Government Department of Health, 2021), which is governed by the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act, passed by each State and Territory parliament in Australia (AHPRA, 2020). Apart from Psychology, examples of the other health practitioner boards include Nursing and Midwifery, Occupational Therapy, Medical, Optometry, Paramedicine, Osteopathy, Pharmacy, and Podiatry. AHPRA has set standards, policies, and guidelines for each of the health practitioner areas and works with each of the 15 national boards to ensure that health practitioners work in accordance with those standards and policies and the public is protected (AHPRA, 2021). The Psychology Board of Australia adopted the Australian Psychological Society Code of Ethics (2007) as the code of conduct with which all psychologists in Australia must comply (Psychology Board of Australia, 2020). Members of the public can search the Psychology Board of Australia (2020) website to check the registration status of psychologists, and the website also has a portal for reporting concerns about a health practitioner to the Board.

To maintain registration, counselling psychologists need to demonstrate that they have met set requirements such as Continuing Professional Development (CPD) each year. The Psychology Board of Australia (2019) website has information about the different types of registration, including Provisional, General, and Area of Practice Endorsement registration, along with the Registration Standards.

As previously mentioned, the Australian Psychological Society (APS) is the peak body in Australia to which psychologists can apply for membership. There are approximately 27,000 members of the APS, including approximately 1,075 members of the APS College of Counselling Psychologists, which is one of the nine colleges that each represent a speciality area (APS, 2021c). The APS has over 40 branches across Australia, so this provides a great opportunity for psychology students to network with psychologists in their local area. The APS also currently has 48 interest groups to which counselling psychologists can belong. These interest groups are very diverse, with some examples being: Psychology of Relationships, Psychology and Ageing, Narrative Therapy and Practice in Psychology, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Psychology, Psychology and Homelessness, Psychology and Yoga, and Trauma and Psychology.

Another professional association for psychologists is the Australian Association of Psychologists Inc (AAPi, 2021a). The AAPi is a relatively new association, formed in 2010, while the APS was first established in 1944. Both the APS and the AAPi provide information, resources, and advice (e.g., on ethical issues) for their members, and they both advertise jobs for psychologists. The APS advertises psychologist jobs on a separate website called PsychXchange (APS, 2021e) and the AAPi has a ‘Psychology Jobs‘ section on its website (AAPi, 2021b). Membership of the APS and/or the AAPi is voluntary and involves an annual membership fee. It’s an individual choice as to whether counselling psychologists join either of these professional associations.

Counselling Psychologist Work Settings

According to the Australian Government National Skills Commission’s Job Outlook website (n.d.), counselling psychologists work in the broad industry areas of Health Care and Social Assistance (53.3%), Education and Training (29.3%), Public Administration and Safety (11.5%), and Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services (3.3%). Within these industries, counselling psychologists work in a range of settings, such as private practice, hospitals and health settings, courts, prisons, justice services, defence, businesses, sport, community agencies, welfare agencies, and educational institutions such as schools and universities (Di Mattia & Davis-McCabe, 2017).

In a survey of 346 members of the APS College of Counselling Psychologists, Di Mattia and Davis-McCabe (2017) found that more than half (59%) worked in private practice as their primary role and 78% per cent were registered as Medicare providers. The other half (49%) of the respondents said that working in private practice was their secondary role. Other contexts included hospitals (7%), counselling services (7%), community agencies (7%), and university departments (5%). In an international study of counselling psychologists across eight countries – including 253 members of the APS College of Counselling Psychologists in Australia – Goodyear et al. (2016) found that four work settings were common across countries. These included private practice/self-employed, university counselling centres, university or professional school faculties, and K-12 educational settings. This study found that almost half (47.4%) of the Australian counselling psychologists surveyed worked in private practice or were self-employed and most participants (67%) were clinical practitioners, with the remaining working in academia (4.8%), administration (3%), consulting (3%), supervision (3%), research (1.3%) or other/missing data (17.8%). Additionally, Goodyear et al. (2016) provided a descriptive summary of members of the APS College of Counselling Psychologists. The majority of counselling psychologists were female (71%), with a master qualification (57%), self-employed in private practice (47%), as a clinical practitioner (67%), applying eclectic or integrative therapy (46%).

The Australian Government National Skills Commission’s Job Outlook (n.d.) website page on ‘Psychologists and Psychotherapists‘ provides some general occupational information, such as average weekly earnings, the average age of people working in these fields, average working hours, skill and education levels, and future prospects. You can see the Job Outlook website for more information.

Counselling Psychologist Roles and Activities

The roles and activities of counselling psychologists are diverse given their expertise in counselling and psychotherapy, mental health disorders, program development and evaluation, mediation, and assessments and report writing (APS, 2021f). Goodyear et al. (2016) found that counselling psychologists’ professional time was spent on the key activities of counselling/therapy (52%), administration/management (22%), assessment (18%), teaching/training (16%), consultation (15%), research (14%), clinical supervision (12%) and prevention activities (9%).

Counselling psychologists provide services to individuals, couples, families, groups, carers, other professionals (e.g., medical specialists and health practitioners), hospitals and health departments, community organisations and community groups, and organisations, such as state or local government organisations, welfare agencies, educational institutions, justice services, and community services (APS, 2021f). Counselling psychologists use a wide variety of evidence-based therapeutic approaches and techniques to provide assessment and psychological therapy for a wide range of presenting issues, including mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression, trauma, substance use disorders, eating disorders, and personality disorders (APS, 2021f). They can also work with clients experiencing issues such as grief and loss, significant life transitions, developmental issues, relationship difficulties, domestic violence, sexual abuse, traumatic events, and career or work issues (APS, 2021f).

Given that psychologists are extensively trained in research, they can also apply their research skills to program development and evaluation. They might be involved, for example, in analysing current treatment programs for specific mental health problems and designing, implementing, monitoring, and evaluating mental health treatment programs (APS, 2021f). Counselling psychologists may also provide mediation services to clients who are experiencing interpersonal or work conflicts (APS, 2021f). Because of their advanced training in psychological assessment, counselling psychologists may also conduct psychological assessments and write reports for individual clients, health and legal professionals, and government departments (APS, 2021f). The types of assessments can include cognitive, personality, and vocational assessments for children, adolescents, and adults (APS, 2021f).

Training Pathways, Registration, and Area of Practice Endorsement for Counselling Psychology

The practice of counselling psychologists in Australia is nationally regulated by the Psychology Board of Australia (PsyBA), which is overseen by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). The pathway to becoming a counselling psychologist involves the completion of a three-year accredited undergraduate psychology program (e.g., a bachelor degree), then the successful completion of a fourth year of accredited psychology studies (e.g., an honours degree), followed by the successful completion of postgraduate study to gain general registration as a psychologist (e.g., a Master of Counselling Psychology), and finally, the completion of the Registrar Program to obtain an Area of Practice Endorsement (AoPE) as a counselling psychologist. This final step involves an additional period of supervision and professional development and typically takes about two years full-time. So, in effect, it takes a minimum of eight years full-time to be eligible to apply for an AoPE as a counselling psychologist.

The 2019 APAC Accreditation Standards outline a range of competencies required for an AoPE as a counselling psychologist. For example, counselling psychologists are required to demonstrate competency in applying their advanced knowledge and skills to work with a broad diversity of clients from a lifespan developmental perspective. They adhere to relevant legislation, codes of ethical practice, and mental health practice standards, and take into account occupational settings (APAC, 2019). The working alliance is pivotal to their practice, which is underpinned by the scientist-practitioner model and is based in a diverse range of theoretical approaches (APAC, 2019). Counselling psychologists are also competent in applying their advanced knowledge of psychopathology and psychopharmacology, psychological and culturally responsive assessment, formulation, diagnosis, and treatment of a broad range of mental health disorders and psychological problems (APAC, 2019). They also apply their knowledge of evidence-based research to psychotherapy processes, therapies, and outcomes for individuals, couples, families, and groups and are competent in designing, implementing, monitoring, and continually assessing their evidence-based interventions for clients (APAC, 2019). They conduct comprehensive assessments and extend their case formulations beyond diagnostic factors to incorporate the client’s sociocultural factors, personal context, treatment preferences, strengths, and resources to tailor their psychotherapeutic interventions to integrate the multiple dimensions of their case formulations (APAC, 2019). As you can see, gaining an AoPE as a counselling psychologist requires extensive training and the ability to demonstrate competency in applying advanced knowledge and skills to a diverse range of clients within a range of different contexts using a diverse range of methods.

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Counselling Psychology

Counselling psychologists are well-trained in research methods and statistics during their university studies because research is a key competency that must be demonstrated at all levels of a psychologist’s training. This means they have a good understanding of how to conduct their own research, how to critically evaluate the research published by others, and how to use a wide range of reputable sources (e.g., peer-reviewed journals) to inform their practice and research.

The practice of counselling psychologists – as with all psychologists – is based on research evidence. A useful resource that guides the provision of psychological services to people with mental disorders is the APS (2018) publication entitled ‘Evidence-Based Psychological Interventions for the Treatment of Mental Disorders: A Review of the Literature‘. The APS has published several such reviews (2003, 2010, 2006, and 2018), which are typically conducted and updated when new mental health care reforms or initiatives are introduced by the government, such as the Better Outcomes in Mental Health Care initiative, the Access to Allied Psychological Services (ATAPS) initiative, and the establishment of the Primary Health Networks (PHNs) (APS, 2018). The latest 2018 fourth edition reports on the results of the most recent literature review. The review covers a broad range of mental disorders, such as mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, eating disorders, sleep disorders, sexual disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder, and pain disorder. It also covers a broad range of psychological interventions, including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT), Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR), family therapy and family-based interventions, hypnotherapy, Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), narrative therapy, play therapy for children, psychodynamic psychotherapy, psychoeducation, Schema-Focused Therapy, self-help, and Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) (APS, 2018).

The APS (2018) literature review bases the levels of evidence on the Australian Government’s National Health and Medical Research Council (2009) evidence hierarchy, with Level I being the highest level of evidence and Level IV being the lowest level. The level of evidence guides psychologists towards the treatment that has received the most empirical support in the literature. For example, if a counselling psychologist is treating a child for conduct disorder (CD), the APS’s research has found interventions such as parent training or CBT can be helpful in the treatment of clinically significant conduct problems of children and teenagers aged 2 to 17 years of age (APS, 2018). This information, along with their clinical judgement, would guide the counselling psychologist on the most appropriate treatment approach for their client. Counselling psychologists who provide services under the Better Access initiative, which provides Medicare rebates to eligible clients, need to ensure the interventions they choose for their clients are covered in the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and therefore meet the requirements for the government funding (APS, 2018). Some of the interventions listed in the APS review might not be approved for use in such government-funded programs (APS, 2018).

Given their extensive research training, counselling psychologists draw from a broad range of sources to identify appropriate evidence-based treatments for their clients. For example, the Cochrane Library (2021) contains a database of systematic reviews and the central register of controlled trials, which are sources of high-quality research evidence that can guide healthcare providers, including counselling psychologists. Counselling psychologists are also skilled in conducting their own research, and the field of psychology has embraced a commitment to methodological diversity that accepts both qualitative and quantitative methodologies as legitimate strategies for generating knowledge. Counselling psychologists who engage in research have a wide variety of international journals to which they can contribute their findings, such as the Journal of Counseling Psychology, the Journal of Counseling and Development, the Counseling Psychologist, and the Journal of Humanistic Counseling, as well as Australian journals, such as the Australian Journal of Psychology, the Australian Psychologist, and the Australian Counselling Research Journal.

Counselling psychologists also draw on practice-based evidence (PBE) to critically evaluate the effectiveness of their services. PBE is formal feedback collected from clients that enables practitioners to determine the effectiveness of their practice with each client. Client feedback measures such as the Session Rating Scale (SRS) (Miller et al., 2002), the Outcome Rating Scale (ORS) (Miller & Duncan, 2000), and the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2) (Lambert et al., 1996, as cited in Beckstead et al., 2003) enable practitioners to track treatment response over time, and adjust treatment as needed. The approach enables counselling psychologists to engage in action research on their effectiveness with every client.

Similarities Between Counselling and Counselling Psychology

As you may have noticed, there are many important areas of overlap between counselling and counselling psychology. An obvious similarity is that both professions focus on helping people. They also share similar developmental influences, which means they’re more philosophically aligned than some of the other allied health disciplines. For example, they both share a value in developmental and educational psychology, humanistic psychology, a non-pathologising stance, and a valuing of the strengths and capacity of the client in the process of recovery (di Mattia & Grant, 2015, McLeod, 2019; Meteyard, & O’Hara, 2015). Two other important perspectives shared by counselling and counselling psychology are their view of the person, and an inclusive view of what constitutes clinical evidence. Both professions draw heavily on humanistic perspectives of humanness, emphasising such qualities as human capacity for self-actualisation and goal-directedness, reflectivity, and in the centrality of relationships and sociability (Cooper, 2009). Both counselling and counselling psychology value the importance of clinical evidence that is drawn not only from randomised clinical trials, but also from practice-based evidence, highlighting the importance of clinical experience in informing practice (King, 2013). Counsellors and counselling psychologists work in similar settings, such as private practice, hospitals and health settings, courts, prisons, justice services, businesses, sports, community agencies, welfare agencies, and educational institutions, such as schools and universities. They also work with similar client groups and with presenting issues. There is also an overlap in some of the different types of therapeutic approaches used by counsellors and counselling psychologists, such as Person-Centred Therapy, Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), Psychodynamic Therapy, and Solution-Focused Therapy. The workforce survey of the counselling and psychotherapy professions in Australian in 2021 highlighted another similarity between counselling and counselling psychology: their respective theoretical and practice orientations (Bloch-Atefi, Day, Snell, O’Neill, 2021). Unlike clinical psychology, counselling and counselling psychology draw on a much broader range of theories. This reflects their shared humanistic backgrounds and a wider view of what constitutes ‘evidence’. In the 2021 survey of counsellors and psychotherapists, a breadth of theoretical orientations was represented, with Person-Centred Therapy the largest by far at 19.5 per cent, followed by Psychodynamic Therapy at 6.3 per cent, CBT at 5 per cent, Eclectic at 4.7 per cent, Solution Focused Therapy at 4.3 per cent, and Couples Therapy at 4.0 per cent. While counselling psychology, like counselling and psychotherapy, is strongly influenced by humanistic and psychodynamic theories, in more recent years, counselling psychology also draws on third wave therapies, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), and Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT). While these more recent therapies have a foundation in behavioural and cognitive approaches, they are also strongly influenced by Eastern philosophies and practices, such as mindfulness, and by more recent advances in the neurological sciences. Many counsellors and psychotherapists are also comfortable drawing on some of the strategies within these third wave approaches, such as mindfulness and self-compassion, as they are consistent with the organismic values of the humanistic therapies.

Differences Between Counselling and Counselling Psychology

Although there are many similarities between counselling and counselling psychology, it is important to note that differences do exist, albeit sometimes subtle ones. Organisationally, counsellors and counselling psychologists are members of different professional associations and have different registration requirements. Counselling psychologists can join either the Australian Psychological Association (APS) or the Australian Association of Psychologists Inc (AAPi), while counsellors can join either the Psychotherapists and Counselling Federation of Australia (PACFA) or the Australian Counselling Association (ACA). Psychologists are also regulated by the federal government via the Psychology Board of Australia under the auspices of the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA).

The profession of counselling has been assessed by the Australian Federal Government to determine whether it too should be registered with AHPRA. Due to the profession’s low level of risk of harm to consumers and its industry-based self-regulatory mechanisms, the Federal Government determined that the counselling profession did not require government regulation (PACFA, 2018). As such, the counselling profession remains self-regulated despite previous efforts to acquire government regulation (Day, 2015). In 2021, a Federal parliamentary committee reviewing the mental health sector has recommended that the registration of professional counsellors be overseen by government (House of Representatives Select Committee on Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2021). Given the high demand for mental health services in Australia, it’s likely that government will take over the responsibility for the registration of counsellors in the future.

There are variations in the training and education requirements of both professions – most notably, the difference in the length of time required to meet the requisite training and supervised practice requirements for each profession. For example, students can complete a three-year undergraduate degree in counselling or psychotherapy to meet the minimum requirements for PACFA membership, although many registered counsellors enter the profession after completing a Master of Counselling degree. A master’s degree is considered by many as the preferred pathway to registration. It involves a minimum of five years of study involving a three-year undergraduate degree (most commonly from a related discipline, e.g., psychology, social work, human services, etc.) and a two-year master’s degree. In comparison, it takes a minimum of eight years to meet the requirements for an AoPE as a counselling psychologist. Counselling psychologists must complete the required pathway for general registration as a psychologist, which takes a minimum of six years, before they can proceed on to further training and supervision to meet the requirements for an AoPE as a counselling psychologist.

While an understanding of a breadth of counselling approaches is taught in both professions, counselling psychology programs tend to require students to have proficiency in at least two theoretical counselling approaches. While counselling programs may focus on specific theoretical approaches, it’s more common to provide students with theoretical breadth and less depth in any specific counselling approach. In counselling programs there is also a strong emphasis on training in interpersonal skills and less training in psychological assessment. Counselling programs in Australia do train students in mental health and psychopathology, as it is a requirement within the profession’s training standards, but there is generally less focus on this than in counselling psychology programs, and when taught, is taught in the context of a critique of the medical model assumptions underpinning diagnostic systems (PACFA Training Standards, 2020).

Counselling psychology training programs in Australia also provide much more education and training related to the assessment and diagnosis of psychopathology. When registered as psychologists, people with this background may also be granted permission to operate under a reserved act to diagnose psychopathology. Unlike counselling psychologists, counsellors are not qualified to diagnose mental health disorders. Similarly, counsellors do not administer restricted psychological tests. Psychological testing is integral to the training of psychologists, and to reduce the risk of harm to the public, many psychological tests are protected and restricted for use by psychologists who are competent in the use and interpretation of psychological tests, or to those working under the direct supervision of a psychologist (APS, 2021d). While other professions such as counsellors may administer assessments that could be regarded as psychological because they tap into psychological concepts, they can only use tests that are not protected, that do not have restricted access, and that are not strictly classified as ‘psychological tests’ (APS, 2021d).

Most counselling psychology programs also have a strong emphasis on understanding and conducting research. They typically subscribe to a scientist-practitioner model of education, with the intent that clinical practice is informed by research evidence. Undergraduate, honours, and postgraduate psychology programs contain a relatively high proportion of training in research and statistics. Although there is an emphasis on research in counselling programs that require a thesis – which is a relatively large document that presents the findings of a research project – they ‘oftentimes embrace a scholar-practitioner training model whereby master’s-level trainees become consumers of research rather than researchers themselves’ (PACFA, 2020).

Below are some tips you might want to consider when making your decision.

1. Look ahead: Do you want to become a counsellor or a counselling psychologist? Although some of the steps are similar, there are some significant differences to be aware of. These differences include, but are not limited to, different training requirements and scopes of practice. It’s up to you to thoroughly research the educational training options and career outcomes to choose the practice that best suits your specific career goal. If you’re unsure which direction to take while studying a three-year psychology undergraduate degree, you still have time to consider whether to continue on to the fourth year (e.g., honours), then on to postgraduate studies in psychology towards general registration as a psychologist, and then to complete further training to be eligible for an AoPE as a counselling psychologist, or whether to commence a postgraduate pathway towards registration as a counsellor. However, if you complete a counselling degree and then decide you want to pursue a career as a psychologist, considerable time and effort may be required as only an undergraduate degree accredited by the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC), completed at the required standard (GPA stipulations), make a candidate eligible to apply for the fourth year (honours), and subsequent master degree, followed by at least two years of supervised practice. Hence it’s important to understand the pathways and requirements for the degree that you choose and know what your options are.

2. Understand registration requirements: In Australia, psychology is a government-regulated health profession, and it’s against the law for anyone who is not registered with the Psychology Board of Australia to call themselves a psychologist. Counselling, on the other hand, is a self-regulated profession. While legally there are no restrictions for anybody wanting to provide counselling services, there is growing public and industry awareness of the importance of counsellors being suitably-trained and registered with PACFA or ACA. The ACA and PACFA websites provide information on which counselling and psychotherapy training is recognised as meeting their respective training standards. Those interested in becoming registered counsellors and psychotherapists on the national ARCAP registry need to ensure they select a training pathway that will lead to membership in PACFA or the ACA. Whether you plan to become a counsellor or a counselling psychologist, you will need to check the registration requirements with the relevant regulatory authorities and/or professional associations.

3. Explore training providers: The Australian Psychology Accreditation Council website (APAC, 2021) has a list of accredited psychology programs. To pursue a career as a psychologist and to go on to gain an AoPE as a counselling psychologist, you will need to undertake study programs that are APAC-accredited. Therefore, it’s important to ensure the study program you enrol in is accredited by APAC. You’ll see the accreditation standards and all the competencies required for psychology training programs in the APAC Accreditation Standards for Psychology Programs (2019).

For the counselling profession, accredited counselling and psychotherapy training will cover core skills and competencies that are required in the ACA (Australian Counselling Association, 2012) and/or PACFA (2020) training standards. However, training providers will have their own training approaches. Some training programs may be more generalist in the modalities taught and encourage students to develop their own personal frame of practice. Others may have more of a specialist focus, perhaps prioritising training in a specific type of therapy. Some will emphasise the use of empirically-supported treatments that are emphasised in psychology programs, while others will emphasise more philosophically-derived, humanistic, creative, or diverse approaches to treatment.

Attendance requirements and educational formats will also vary. While all counselling courses will require some face-to-face attendance, distance classes may meet the attendance requirements in residential schools, while other training providers will require regular on campus attendance.

4. Check prerequisites – well in advance: Each psychology and counselling study program will specify pre-requisite courses, so when you decide on your program of study, make sure you follow the recommended enrolment plan if possible. If this is not possible, then seek some help from your university to ensure that your enrolment is correct. Psychology honours and master’s degrees in Australia typically require research skills and knowledge to be taught, and some of these will require writing a thesis. The same applies for master’s degrees in counselling. If you intend to undertake a doctoral program after a Master of Counselling, note that many doctoral programs require a master’s thesis to demonstrate one’s ability to complete a significant research project. Knowing prerequisites in advance will help you make decisions regarding program streams and/or elective courses that will keep doors open for your preferred next steps. You can investigate these requirements through using university program websites or connecting directly with counselling or psychology program or course coordinators. Programs and entrance requirements can change, therefore it’s prudent to review the entrance requirements on the institution’s websites or connect directly with relevant staff in your program(s) of interest rather than rely on past student advice.

5. Confirm admission requirements: Aside from specifying prerequisites, many university study programs will have other admission requirements. By exploring your chosen university early, you can ensure that your grades, volunteer or work experience, letters of reference, and other admission criteria meet or exceed the requirements and maximise your chances of being selected into your chosen program of study. Again, programs and entrance requirements can change, so it’s prudent to ensure you gain information from the educational institution itself, and that the information is current.

6. Understand employer expectations: There will be regional differences as well as differences related to areas of specialisation and places of employment for both counsellors and psychologists. Consider the type of work that you’d like to do when you graduate and ensure that your course work, field training (practicum or internship) hours, supervisors’ qualifications, professional designation, and work experience work together to prepare you well for work as a counsellor or counselling psychologist. Investigate your desired career options and clearly identify necessary qualifications prior to beginning your studies. Ensure the program you enrol in meets your desired career qualification requirements.

Making a Choice

There are so many similarities between counsellors and counselling psychologists, which can sometimes make it difficult to decide which profession you might like to pursue. This is where Chapter 2 might be useful for you to read if you haven’t done so already. When you make career decisions, it’s important to have a good understanding of yourself and the influences on your career choices. Having a good understanding of your values, personality, interests, abilities, aptitudes, and skills is a great start. It’s also important to understand other significant influences, such as where you live/want to live, the employment market, the availability of jobs in your chosen area, your age, your finances, and the political climate. Some people find it helpful to write a list of what is most important to them and weigh up each of those factors – for example, on a scale from 1 (least important) to 5 (most important). Examples of what people deciding between counselling and counselling psychology might identify as important to them might be: salary rate, type of training, length of training, cost of training, ability to work in a specific work context, being able to get a job in the area they want to live, being able to work in a variety of contexts, the professional title, flexible work options, ability to work under the Medicare system, and so on. The key thing is for you to decide what is most important to you and give each one of those things a relative weighting.

Once you’ve given each of your decision factors a relative weighting from 1-5, explore each of the different professions further in relation to those important decision factors. As you will see in Table 2.2 in Chapter 2, you can find information about different occupations, such as weekly pay and future growth, from the Job Outlook website. Keep in mind that this information is typically based on averages, so it doesn’t give you very specific information.

We hope the information in this chapter gives you a general understanding of counselling and counselling psychology, along with the similarities and differences between them. We encourage you to delve deeper by talking to people who are working as counsellors and counselling psychologists, particularly in the contexts within which you would ideally like to work (e.g., private practice, hospitals or health services, schools, community services, etc.) to find out more about their jobs. Also talk to higher education training providers to get more detailed information about the study and training requirements. Try to focus your questions mostly on the key factors you have identified as important to you when making a decision. Once you have sufficient information, you could rate how well each profession aligns with each of the important decision factors you’ve listed – again on a scale from 1 (doesn’t align well) to 5 (aligns really well). Hopefully this will help if you’re trying to decide between counselling and counselling psychology. Once you’ve made a decision, you’re not bound by it if you change your mind down the track. For example, some students complete a three-year psychology degree and decide they don’t want to pursue the pathway to psychology registration, or they may not meet the eligibility requirements for entry into the fourth year of psychology. Instead, they undertake a graduate counselling program and pursue a career as a counsellor. Alternatively, some students may decide to study a combined undergraduate degree which includes both counselling and psychology, while others may start studying counselling and decide to change to psychology.

Conclusion

Counselling and counselling psychology are both growing professions in Australia. While they’re distinct professions, they share similar roots, serve clients of all ages dealing with a wide range of problems in living, and work in similar contexts. Both counselling and counselling psychology offer diverse and engaging opportunities for work, career growth, and varied career paths. Some of the key differences are in the length and type of training. The training for psychologists is typically longer than for counsellors. This is influenced by the Australian Government’s regulation of health professionals and the concomitant registration requirements for psychologists. At present, the counselling profession is self-regulated, as it has not been deemed necessary for the government to regulate it. Additionally, the title of ‘Psychologist’ is protected by law and only a person who has been granted general registration with the Psychology Board of Australia can call themselves a psychologist. The title of ‘Counselling Psychologist’ is also protected by law, with only registered psychologists with a Psychology Board of Australia-approved Area of Practice Endorsement able to call themselves a counselling psychologist. The title of ‘Counsellor’ is not currently protected, however, there are requisite standards for membership of PACFA and the ACA – the professional associations for counsellors and psychotherapists. Choosing between the two professions can be difficult, so think about who you are and what is important to you, and find out as much information as you can about the different options, including talking to counsellors and counselling psychologists and universities that provide the relevant training programs to help with your decision-making. Keep in mind there is some flexibility – particularly when you’re completing your undergraduate studies or after you graduate with your three-year degree. You can easily change from psychology to counselling.

This chapter has been adapted by:

- Nathan Beel, Senior Lecturer (Counselling), University of Southern Queensland

- Nancey Hoare, Senior Lecturer (Psychology), University of Southern Queensland

- Michael Davies, Associate Professor, Australian Institute of Professional Counselling

- Denis J. O’Hara, Senior Lecturer, The University of Queensland

- Jan du Preez, Senior Lecturer (Psychology), University of Southern Queensland

It has been adapted from Borgen, W. A., & Neault, R. A. (2019). Applications and careers for counsellors and counselling psychologists. In M. E. Norris (Ed.), The Canadian Handbook for Careers in Psychological Science. Kingston, ON: eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY NC 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/applications-and-careers-for-counsellors-and-counselling-psychologists/

Send us your feedback: We would love to hear from you! Please send us your feedback.

Copyright note: Permission has been granted by the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia to use their content. Their content is excluded from the Creative Commons licence of the book and cannot be reproduced without permission from the copyright holder.

References

Allied Health Professionals Australia (AHPA). (2021). Members: Australian Psychological Society. https://ahpa.com.au/our-members/australian-psychological-society/

Armstrong, P. (2006). The Australian Counselling Association: Meeting the needs of Australian counsellors. International Journal of Psychology, 41(3), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590544000130

Australian Association of Psychologists Inc. (2021a). Australian Association of Psychologists Inc. [Home page]. https://www.aapi.org.au/

Australian Association of Psychologists Inc. (2021b). Psychology jobs. https://www.aapi.org.au/Web/CareersCPD/psychologyjobs/Web/Jobs-and-training/Psychology%20Job-Board.aspx?hkey=d2fbdd86-83f7-480d-bb91-8db62e743bd8

Australian Counselling Association. (2012). Accreditation of counsellor higher education courses. https://www.theaca.net.au/documents/ACA%20Accreditation%20of%20Counsellor%20Higher%20Education%20Programs%202013.pdf

Australian Counselling Association. (2020). Scope of practice for registered counsellors (2nd ed.). https://www.theaca.net.au/documents/Scope_of_Practice_2nd_Edition.pdf

Australian Counselling Association. (2021). Membership. https://www.theaca.net.au/becoming-a-member.php

Australian Government Department of Health. (2021a). Better Access initiative. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/better-access-initiative

Australian Government Department of Health. (2021b). National Registration and Accreditation Scheme. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/national-registration-and-accreditation-scheme

Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. (2021). National boards. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/National-Boards.aspx

Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. (2020). Legislation. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/About-Ahpra/What-We-Do/Legislation.aspx

Australian Psychological Society. (2007). Code of ethics. https://psychology.org.au/getmedia/d873e0db-7490-46de-bb57-c31bb1553025/18aps-code-of-ethics.pdf

Australian Psychological Society. (2018). Evidence-based psychological interventions for the treatment of mental disorders: A review of the literature (4th ed.). https://psychology.org.au/getmedia/23c6a11b-2600-4e19-9a1d-6ff9c2f26fae/evidence-based-psych-interventions.pdf

Australian Psychological Society. (2021a). Counselling psychologists. https://psychology.org.au/for-the-public/about-psychology/types-of-psychologists/counselling-psychology

Australian Psychological Society. (2021b). Member Groups: APS College of Clinical Psychologists. https://groups.psychology.org.au/cclin/

Australian Psychological Society. (2021c). Member Groups: APS College of Counselling Psychologists. https://groups.psychology.org.au/ccoun/

Australian Psychological Society. (2021d). Psychological tests and testing: Position statement. https://psychology.org.au/about-us/what-we-do/advocacy/position-statements/psychological-tests-and-testing

Australian Psychological Society. (2021e). PsychXchange. https://www.psychxchange.com.au/JobSearch.aspx

Australian Psychological Society. (2021f). Types of psychologists-counselling psychologists. https://psychology.org.au/for-the-public/about-psychology/types-of-psychologists/counselling-psychology

Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC). (2019). Accreditation Standards for Psychology Programs: Effective 1 January 2019 Version 1.2. https://www.psychologycouncil.org.au/sites/default/files/public/Standards_20180912_Published_Final_v1.2.pdf

Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC). (2021). APAC-accredited psychology programs. https://www.psychologycouncil.org.au/APAC_accredited_psychology_programs_australasia

Beckstead, D. J., Hatch, A. L., Lambert, M. J., Eggett, D. L., Goates, M. K., & Vermeersch, D. A. (2003). Clinical significance of the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2). The Behavior Analyst Today, 4(1), 86–97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0100015

Beel, N. (2017, May). “But we do that too”! Terminology and the challenges in differentiating the counselling profession from other professions who counsel. PACFA eNews, 16–17.

Bloch-Atefi, A., Day, E., Snell, T., O’Neill, G., Gaskin, C. (2021). A snapshot of the counselling and psychotherapy workforce in Australia in 2020: Underutilised and poorly remunerated, yet highly qualified and desperately needed. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, Advanced online publication, https://pacja.org.au/2021/10/a-snapshot-of-the-counselling-and-psychotherapy-workforce-in-australia-in-2020-underutilised-and-poorly-remunerated-yet-highly-qualified-and-desperately-needed/

Borgen, W. A., & Neault, R. A. (2019). Applications and careers for counsellors and counselling psychologists. In M. E. Norris (Ed.), The Canadian handbook for careers in psychological science. eCampusOntario. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/applications-and-careers-for-counsellors-and-counselling-psychologists/

Brear, P. D., & Dorrian, J. (2010). Does professional suitability matter? A national survey of Australian counselling educators in undergraduate and post-graduate training programs. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 32(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-009-9084-2

Brown, J., & Corne, L. (2004). Counselling psychology in Australia. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 17(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070412331317567

Burton, L., Westen, D., & Kowalski, R. (2019). Psychology: Australia and New Zealand edition (5th ed.). John Wiley and sons.

Cochrane Library. (2021). About the Cochrane library. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/about-cochrane-library

Cooper, M. (2009). Welcoming the other: Actualising the humanistic ethic at the core of counselling psychology practice. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(3&4), 119–129. https://mick-cooper.squarespace.com/new-blog/2021/5/1/welcoming-the-other-actualising-the-humanistic-ethic-at-the-core-of-counselling-psychology-practice

Davis-McCabe, C., Di Mattia, M., & Logan, E. (2019). Challenges facing Australian counselling psychologists: A qualitative analysis. Australian Psychologist, 54(6), 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12393

Day, E. (2015). Psychotherapy and counselling in Australia: Profiling our philosophical heritage for therapeutic effectiveness. Psychotherapy & Counselling Journal of Australia, 3(1). http://pacja.org.au/?p=2413

Di Mattia, M., & Davis-McCabe, C. (2017). A profile of Australian counselling psychologists. InPsych, 39(2). https://www.psychology.org.au/inpsych/2017/april/dimattia

Di Mattia, M. A., Grant, J. (2015). Counselling Psychology in Australia: History, status and challenges. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 29(2) 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2015.1127208

Di Mattia, M., & Grant, J. (2016). Counselling psychology in Australia: History, status and challenges. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 29(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2015.1127208

Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

Gazzola, N. (2016). Is there a unique professional identity of counselling in Canada? In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 1-12). Ottawa, ON: CCPA.

Goodyear, R. K., Lichtenberg, J. W., Hutman, H., Overland, E., Bedi, R., Christiani, K., & Young, C. (2016). A global portrait of counselling psychologists’ characteristics, perspectives, and professional behaviors. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 29(2), 115–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2015.1128396

Grant, J., Mullings, B., & Denham, G. (2008) Counselling psychology in Australia: Past, present and future- Part one. The Australian Journal of Counselling Psychology, 9, 3-14.

Haverkamp, B. E., Robertson, S. R., Cairns, S. L., & Bedi, R. P. (2011). Professional issues in Canadian counselling psychology: Identity, education, and professional practice. Canadian Psychology, 52, 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025214

Hanna, F. J., & Bemak, F. (1997). The quest for identity in the counseling profession. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36(3), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1997.tb00386.x

House of Representatives Select Committee on Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. (2021). Mental health and suicide prevention – Final report. Commonwealth of Australia. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportrep/024705/toc_pdf/MentalHealthandSuicidePrevention-FinalReport.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf

King, R. (2013) Psychological services under Medicare: Broken but not beyond repair. Psychotherapy in Australia, 19(2), pp. 38–42.

Lewis, I. (2015). Vision for the future? The contribution of the Psychotherapy and Counselling. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 3. Online. http://pacja.org.au/?p=2460

Littlefield, L. (2017). Ten years of Better Access. InPsych, 39(1), 7–10. https://psychology.org.au/inpsych/2017/february/littlefield

Meteyard, J., & O’Hara, D. J. (2015). Counselling psychology in Australia. Counselling Psychology Review, 30(2), 20–31.

McLeod, J. (2019). An introduction to counselling and psychotherapy (6th ed.). Open University Press.

Miller, S. D., & Duncan, B. L. (2000). Outcome Rating Scale. https://www.scottdmiller.com/fit-software-tools/