2 Reducing and reviewing content

Introduction

The core strategy underpinning microlearning is to increase learner engagement by reducing barriers to learning. Increasing learner engagement is a proven pathway for increasing learner outcomes and accounts for microlearning’s success (Kamel, 2018; Kapp & Defelice, 2019; Torgerson, 2021).

Volume overload, and perceptions of high volume are at the forefront of why learners find learning difficult, (and even the prospect of learning on first encountering materials overwhelming), make learning look unappealing and demotivating. Lifeload demand pressures, like: part and fulltime work, family and caring responsibilities etc. also add to the load and overall stress learners have to deal with in learning (discussed in Chapter 1).

A central design principle in microlearning is ‘less is more’ - as a mindset to reduce cognitive load in learning and the anxiety it brings. While cognitive overload is an impediment to information comprehension, absorption and attracting interest, it also adds to the difficulty of being able to see the value and relevance of the content being covered, and this can lead to disengagement.

Microlearning seeks to address these barriers to engagement with its focus on optimising instructional design to help make learning resources and experiences more attractive and engaging for students by reducing volume in content based on relevance and practical value.

Reviewing content to reduce volume in learning materials like written modules (often called course guides or lecture or notes), along with set readings and video resources, is a good place to make a start. If you are able, to begin by reviewing course learning objectives, better still. Or, one step further, reviewing whole degree program objectives, or the objectives of a Major in a program.

But in all cases, we can use the following kind of question to guide us through our review of materials:

- Do the learning objectives and content fit current industry and educational requirements?

These content reduction and selection principles are also applicable when developing new courses and curriculum.

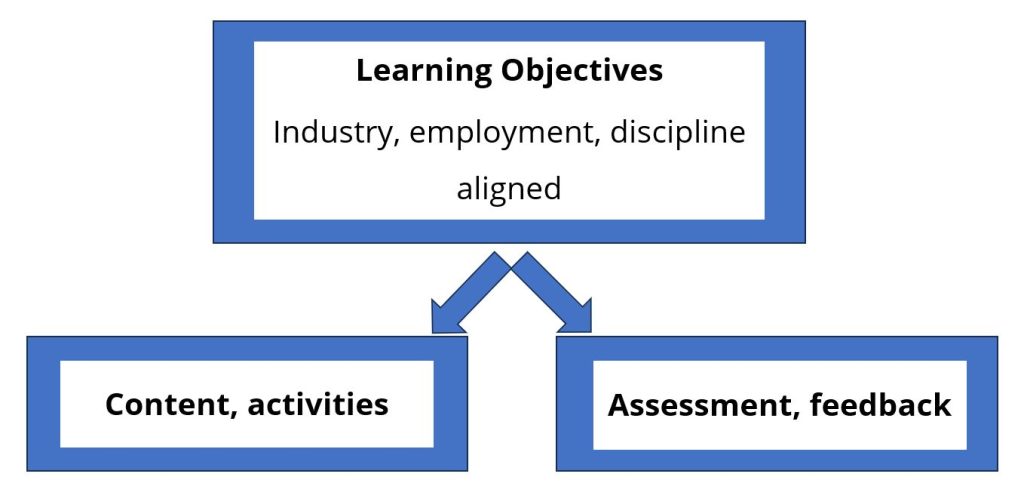

Constructive alignment

Constructive alignment is an approach to learning design that helps ensure consistency between learning objectives, course content and assessment (Biggs & Tang, 2011). We can also draw on it as an approach to help us audit courses so that we can remove objectives that are no longer relevant and add new and up-to-date objectives where needed.

Auditing learning objectives involves ensuring continued alignment with the current needs and demands of industry (i.e., industry alignment), as well as Higher Education (HE) e.g., quality compliance.

Constructive alignment

As a starting point, we can think about constructive alignment by contrasting it with its opposites:

- courses with imprecise, unclear or ambiguous learning objectives

- content that is not aligned with stated learning objectives and assessment

- content that is not industry aligned

Once learning objectives have been bedded down, do not stray, keep content within the stated course objectives. Keep in mind, our goal is to reduce unnecessary load.

Reviewing and streamlining content involves running frequent checks to make sure that the content matches the stated learning objectives. This then follows through to assessments to ensure consistency with assessments. Quality design means all components are matched and fit together. Course learning objectives (CLOs) should also be included in assessment instructions and in assessment marking criteria.

Relevancy or value can also be included in assessment instructions but kept brief and partitioned to avoid unnecessary overloading and diverting of attention for learners trying to interpret assessment instructions.

Having CLOs in Marking Criteria forms, also helps close the loop in constructive alignment in ensuring consistency and congruency between CLOs, course content, assessment design and instructions, and the marking criteria used to grade assessments (see Marking Criteria Rubric, below).

| Course learning objectives (CLOs) | HD | A | B | Pass | Fail |

| CLO 1 Communication – expression, – grammar, – spelling, – writing /10% |

Exceptionally high in spelling, punctuation, grammar, clarity of written expressions. | Very high standard in spelling, punctuation, grammar, and clarity of written and expression. Very high standard in spelling, punctuation, grammar, and clarity of written and expression. | Reasonable standard spelling, punctuation, grammar, expression. Some lapses and errors apparent. |

Poor but passable spelling, punctuation, grammar, and expression. Recurrent errors and instances of poor, unclear expression. |

Poor standard in spelling, punctuation, grammar. Frequent errors and instances of poor, unclear expression. |

| CLO 2 Referencing and Support /20% |

Exceptionally high standard of academic support: Correct referencing Very high quality and quantity of relevant sources. Course resources very well utilised. |

Very high standard of academic support: Mostly correct referencing. High quality and quantity of relevant sources Minimal errors Course resources well or reasonably well utilised. |

Reasonably sound referencing support: Errors apparent Course resources could be better utilised. |

Poor but sufficient /passable standard of academic support: Recurring errors Poor quality and/or quantity: sources Course resources could be better utilised. |

Very poor standard of academic support: Many errors apparent Poor quality and/or quantity: sources Course resources could be much better utilised. |

| CLO 3,4,5 Understanding application content/concepts & originality /30% |

Demonstrates very thorough and advanced understanding and application of course content and concepts. Advanced interpretation and originality. |

Demonstrates thorough and advanced understanding and application of course content and concepts. Notable degree of originality of thought. |

Demonstrates reasonably sound understanding and application of course content and concepts. A degree of originality of thought. |

Demonstrates somewhat poor understanding and application of course content and concepts. More engagement with course content to improve. |

Does not demonstrate an adequate understanding of and application relevant course content and concepts. |

| CLO 6 Analysis and Strength of Argument /30% |

Exceptionally high standard of synthesis and analysis of ideas & course content; and strength of reasoning and argument to support points. | Very high standard of synthesis and analysis of ideas & course content; strength of reasoning and argument to support points made. | Sound standard of synthesis and analysis of ideas & course content; reasoning and argument. More argument and analysis as opposed to descriptive work to strengthen. | Poor or often poor but sufficient standard of analysis of ideas & course content; reasoning and argument. More argument needed as opposed to descriptive work. |

Poor standard or insufficient analysis of ideas & course content; and reasoning and argument. More argument needed as opposed to descriptive work. |

Note, marking rubrics often include feedback built-in with detail on level of performance on criteria. In doing so they provide guidance on areas where further development could strengthen the quality of work.

Marking and feedback are a ‘bottom-line’ matter, for educators as a measure of learning performance, and also for students.

AUDIT QUESTION: Is the design of this assessment appropriate and reliable for assessing knowledge and abilities as stated in the learning objectives and required for professional performance?

Selection and reduction: relevancy and practical value

My success in teaching has been based on relevancy and practical value, which has a natural and logical fit with microlearning. Reduce content with selection based on usefulness to students in relation to value and practicality for: employability; professional work competencies and for producing quality assessments. This helps in aligning content, optimising learner relevance and managing cognitive load. It also makes it easer to answer a student who asks, ‘Why do I need to know this?'

We can start reduction of content, module by module, and then follow through to the other learning resources, like reducing set readings and videos.

Core criteria for retaining and selecting content based on relevance and practical value:

- Employability: building industry-relevant proficiency: e.g. PR work performance, strengthening employability.

- Assessment: aiding learners to produce high quality assessments in efficient ways.

Employability

The criterion of employability divides into subcategories of (a) technical knowledge, including skills specific to a profession (or discipline), then (b) job specific transferable-based skills and knowledge, these are transferable to a degree, but also specific to a given industry or profession, and then (c) generic transferable skills, which are more general and applicable across professions. Employers today prioritise these competencies to the level ‘essential’ in recruiting and selecting employees. This boosts their relevancy to curriculum.

The term 'graduate attributes' is also used to refer to transferable skills and knowledge competencies that are linked to, and aligned with, employability - and used in HE institution quality assurance required by government. Graduate attributes are largely derived from studies into employability that involve input from employers and graduates working in industry (Chan et al., 2017; Suleman, 2018).

Summing up, employability areas can be divided into the follow categories.

-

- Technical profession-specific: profession-based knowledge and skills

- Transferable job-specific: general skills and knowledge, that are highly specific to a profession

- Transferable generic: general skills and knowledge that are widely applicable across industries or employment broadly and for life and career success

- Career and employability curriculum: inclusion of career literacy is increasing

Profession specific technical skills and knowledge

This section outlines technical and transferable skills in the public relations discipline area as an illustration of the considerations that need to be made when reviewing learning objectives and retaining and selecting content based on relevance and practical value. In the case of public relations, professional technical knowledge for public relations includes being able to create written content in ways that are specific to the profession, for example, writing in styles that are suitably journalistic, (e.g., ordering information according to its importance), and in styles that are publishable and suited to a variety of specific media (e.g., media releases, social media posts). Skills and knowledge in being able to use current platforms and applications for producing outputs are essential, including writing in Word Press and Adobe InDesign in place of Microsoft Word, and competence in using Adobe Illustrator for graphics. Competency with platforms required for disseminating outputs is also essential. So is the continuing importance of social media and keeping up to date with proficient use of social media, so much so, that this is now well embedded throughout the curriculum in public relations.

Profession based skills and knowledge also include the theoretical knowledge that employers expect graduate practitioners to hold. In the case of public relations, theoretical knowledge employers consider essential includes Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), and theory on Stakeholder Engagement and related practices e.g., Two-Way Symmetric Communication and Mutual Benefit decision-making principles (Eggensperger & Salvatore, 2022; Smith, 2022).

Critical 'threshold' content

Critical and threshold are high priority content areas in microlearning design, the knowledge and skill areas essential for competence in profession and discipline, and, for progressing with study in an area. Formal writing for assignments, especially, essays and long form writing, is common area of difficulty among my public relations students. So, I cover essay and long form writing as a priority area of need by presenting students with the most common pitfalls people encounter when writing essays and how to avoid these by guiding students through step-by-step planning methods to help them stay on track and write efficiently (as shown in essay learning design in Chapter 4).

Microlearning design can also be used in other discipline areas, for example, to address critical mathematics skills and knowledge, by breaking complex processes down into smaller steps to allow students to build their capacity and make complex processes more achievable in areas where students experience more difficulty (Alias & Razak, 2024; Chamorro-Atalaya et al., 2024; Wijaya et al., 2022).

We can determine these high priority areas in course reviews to identify, and take into account, common struggle points. We should also look out for, and include where needed, necessary and expected prerequisite knowledge. We can begin by gathering intelligence in course audits and reviews including from student feedback and our experiences in running the course.

Tackling common struggle points or deficits can then be addressed by integrating ‘support-designed’ content and skill development into courses to help overcome these stumbling blocks and minimise their flow-on effects. Putting these kinds of measures in place can save lecturers and students a great deal of time and angst, which makes for a good return on investment.

Profession specific transferable skills and knowledge

Transferable skills and knowledge required for professional competency in public relations include being able to write well. Dimensions of public relations writing include: writing in informative-story form; writing clearly, concisely and precisely; writing in ways that is easy to read and understand; writing in ways that appeal to general and target audiences; and demonstrate mastery of grammar and punctuation. Then, in addition to these professional-practice based ways of writing, more formal and academic forms of writing, like essay writing, become useful because they help students build and integrate an array of skills, such as conducting research, gathering and arranging information, and applying logic for case building, which are useful for and can be applied in professional work, that is, they have high levels of transferability.

Many employers of public relations graduates, believe essay writing provides students with valuable practice and preparation in learning how to write well and to do so in extended forms that are often required, for example, case building for campaign proposals, evaluation reports, and long-form magazine style prose for feature articles (Johnston & Glenny, 2021; Macnamara, 2018; Mahoney, 2017).

Generic level transferable skills and knowledge

Transferable skills and knowledge at this more general level are given high priority in HE education program design today. Global employer surveys across all disciplines identify generic transferable skill areas as critically important (Pennington & Stanford 2019; Quacquarelli Symonds, 2019; World Economic Forum [WEF], 2018). This is also reflected in graduate job selection criteria where they are commonly classified as essential. Employers often refer to these as ‘employability skills’.

Commonly include:

- problem-solving

- critical thinking and analysis

- adaptability

- interpersonal skills

- teamwork (ability to cooperate, negotiate, coordinate, lead and motivate).

My recent research with public relations employers (Kossen et al., 2025) revealed that they rate transferable skill and knowledge areas more highly than profession specific skills and knowledge. Why is this the case?

Research also shows that the majority of those employing graduates, (including employers of public relations graduates), view generic transferable skill areas as more durable i.e., longer lasting, than those in the technical or profession specific domain, due to the shorter shelf-life of profession specific skills and knowledge areas (Macnamara, 2018; Olesen et al., 2021). The lifespan of a good deal of specific professional ‘know-how’ knowledge is shortening at a faster pace as the pace of change continues to accelerate. Public relations employers involved in my recent graduate employability study stressed that they themselves found keeping up to date with change a struggle (Kossen et al., 2025).

Of note, public relations employers identified independent learning (interchangeable terms include life-long learning, self-directed learning) at the top of their priority list in recruitment decision-making. They felt that the ability to be able to learn independently gives those entering industry the ability to adapt and keep up with change. Independent learning is a higher order transferable skill which incorporates subset transferable skill components, like critical thinking and analysis and problem-solving.

Public relations employers also viewed emotional skills, especially enthusiasm and eagerness to learn, as playing a critical role in an employee’s capacity for learning, adaptability and keeping pace with change. For example:

They can’t be expected to come in and know everything, but if they want to learn and grow then that is the most important thing of all because skills can be learned by those that have this attitude. That is why it is so important. (Public Relations Employer)

Employers viewed these traits as ultimately more important than being across all profession specific knowledge areas, because these can be acquired by employees who have a well instilled willingness to learn. For these reasons employers of public relations graduates (Kossen et al., n.d.) stressed that it is very important for educators today to place a great deal of focus on developing these general ‘transferable’ capacities as a part of the curriculum for meeting industry and employability needs.

My colleague Michael Howard (University of Southern Queensland) and I provide an overview on the nature and the role of generic level transferable skills in education in PODCAST EPISODE 4 from 'Communicating for Success' (audio; 6'26"; CC-BY). Public relations work, as a profession example, involves dealing with and relating to people and communities and this requires interpersonal skills that help facilitate cooperation, negotiation and managing conflicting priorities between parties tactfully. These skill areas, often called ‘people skills’, overlap with life skills. People draw on these to manage their lives, e.g., to manage personal relationships like friendships. They are transferable, they have high applicability for professional settings and relationships.

Career and employability learning curriculum (CEL)

Employers today expect graduates to be able to demonstrate the value of their transferable skills with evidence of their ability to apply these to work-type situations, for example, interpersonal and problem-solving skills feature strongly in position descriptions and selection criteria. However, many graduates and job seekers have great difficulty in communicating and demonstrating the value of their achievements and abilities in relation to these selection criteria within their profession (Bridgstock, 2009; OECD, 2019). Accordingly, I incorporated Career and Employability Curriculum (CEL) in recent years to further strengthen employability in public relations teaching. It is an example of microlearning content selection based on relevance and practical value.

Case study: The impact of an employability focused curriculum on a final year course

CEL has proved to be highly and particularly successful in the case of my final-year level course, Organisational Communication and Culture, which has a CEL focus on transition to employment. CEL curriculum adopted in this course was designed to assist learners in preparing themselves to maximise their employability (i.e., attractiveness to employers) with timely and effective transition into employment, and ideally, into employment for which they are well-suited. Skill and knowledge content incorporated into the course included: how to generate evidence for individual employment portfolios, undertaking occupational research and scanning, addressing selection criteria as well as professional networking and profile marketing (e.g., LinkedIn profiles). These topics and skills areas were built into course assessments to provide students with opportunities to apply their learning on these topics in relation to their individual circumstances and benefit further from constructive feedback provided.

The course has consistently rated very highly with students since incorporating microlearning and the CEL employability initiative in 2019 and was well received by the ten employers consulted to evaluate the curriculum (see USQ 2022, Teaching Excellence Showcase Poster link/QR code below). Feedback revealed that students were very pleased with the quality of the curriculum and valued the curriculum for its opportunity to learn and apply practical skills and knowledge which prepares them for a smoother transition into employment.

It was really helpful having it come from the university, that they wanted to support you with that transition rather than just sort of finishing up… then it almost feels like you’re being kicked out on your bum. (Public Relations Student)

The CEL employability initiative was supported through obtaining USQ Excellence in Teaching grant funding. I have included this case example because it clearly involves microlearning and is a good demonstration of what is possible and can be achieved with microlearning. I have used it here to demonstrate and inspire, not overwhelm.

Assessment

Selecting content based on its usefulness to students for producing quality assignments and assessments aligned to course objectives is an obvious and effective way to approach not only reduction, but also increasing and ensuring high relevancy content for learners. Assessments are of utmost importance in learning. They are the measure we use to determine pedagogical effectiveness and learning performance. They are very much the ‘bottom-line’ for students and for educators. Assessments are at the centre of both, providing and assessing professional preparation for students, and hence highly relevant and practical, in developing professional work competency and future employment. This shows how microlearning design incorporates constructive alignment principles to ensure assessments meet profession competency requirements, and how the criterion of employability is used to guide content selection and reduction.

Relevance linking should also be included in the instruction section for each assessment by providing explanations that make the practical value of an assessment explicit by in relation the role it plays in developing valuable and essential skills and competencies for success in given industry or profession/s.

As mentioned earlier, we should also make these links frequently in course modules as well as in lectures, classes and presentations. A point to note here, is that while microlearning design is largely about reducing volume, by removing unnecessary redundancy, e.g., repetition - strategic or well-placed redundancy plays an important role in keeping learning focused. Relevance linking, is a prime example, linking to relevance and benefits of material being covered, frequently (yet not too frequently). We use repetition strategically because it helps learners keep focused and engaged and we rely on our judgement to achieve optimal balance.

This video segment from 'Microlearning presentation' 2022 (4'00"; CC-BY), discusses reducing volume in content.

Decluttering

In combination with relevance and practical value, the idea of decluttering is a useful way to think about and approach reduction. For instance, in helping guide decisions (a) source some shorter reading resources and (b) dispense with resources that do not seem necessary or of low importance. Reviewing your course is a great opportunity for decluttering for 'spring-cleaning' refreshing.

It is worth pausing for thought here, the majority of us, as educators, have a tendency to write too much when writing modules (course notes) and so they become unnecessarily high in volume. While we’re trying to pack in as much value as possible for our students, it is one of the biggest pitfalls in writing learning content, believing that ‘more is more’. While the intention is good, we create overload and clutter, and this reduces value, rather than adding to it. Our own mindfulness and vigilance about this is our best defense against this common pitfall. This points also helps demonstrates the importance of adopting microlearning as a ‘perspective’ when developing learning materials. It is a perspective that helps us see that pruning material is usually necessary, or at least, beneficial.

Reducing and decluttering involves reviewing module content and learning resources critically and try to approach them more objectively, with fresh eyes. The questions below are focused on course readings to help demonstrate a process, the kinds of questions used here can be applied to other learning materials such as videos.

These questions can help guide thinking and focusing for decluttering set readings:

- Is this reading necessary?

- Is it relevant enough? Is it critical, is it valuable enough?

- Would removing this reading reduce course quality and learning needs?

- Do I need to retain the whole chapter as a reading, or could I just specify which pages are relevant?

- Would summarising key points from a reading be effective?

- Is there a better reading available? - a clearer, more concise, less unnecessarily complex reading available?

Students are much more likely to read set readings if we confine them to one or two short readings. Content curation plays an important role in our profession as educators. We are always looking out for stimulating, interesting and highly relevant resources, and the shorter the better, whether they be readings, videos or podcasts. Sourcing peer assistance or collegial opinion in searching for and deciding on course resources is worth considering, another could be to invite students to help identify resources, this can also help increase engagement.

Criteria for selecting video learning resources

- Videos that are as short as possible (micro)

- Attention-attractive (interesting)

- Relevant and value-adding (with learning objectives in mind)

- Comprehensible: clear, concise, precise, effective in conveying information (easy to understand explanations, demonstrative examples)

- Provide specific time segments that learners should view when using longer videos

Decluttering: slides

In addition to writing and presenting written modules, we should apply decluttering principles to our lectures and slides. Reducing, so there are fewer points on any single slide and take opportunities to reduce text, dot points typically work better than sentences and paragraphs. Also aim to use fewer slides when planning a presentation, but avoid doing so at the expense overcrowding slides, it is better to spread content out. Take opportunities to replace or reduce text with graphics, graphs and tables, for example, can be powerful conveyers of information. Infographics can also convey ideas more effectively and can also be used to make slides crisp, clear and uncluttered.

Infographics

Graphic visual representations of information, data, or knowledge intended to present information quickly and clearly. These can improve cognition by utilizing graphics to enhance the human visual system's ability to see patterns and trends.

Simple icons (below): Heart (icon) Hand (caring) Clock (time management) Cognitive load

![]()

Infographics and graphics can bring many benefits, e.g., attract attention and add appeal, if we avoid too many on one slide, otherwise they too become clutter. Graphics can be also used to help break up text, and large blocks of text. But when overused they become distracting and add to load rather than ease it.

While not wanting to undermine the power of graphics, they are not always necessary, for example, I often present with dot points only. However, formatting for visual appeal and for ease of readability, like, choice of slide styles and backgrounds, choice of type-fonts and line spacing are all important. Managing these kinds of elements efficiently is often best achieved by keeping things plain and simple. Dot points on a white background can work well. Simple variance, like changes to backgrounds, can keep presentations fresh, for little effort.

Litmus test questions to ask ourselves when we design slides and arrange content include:

- ‘Are they easy to read and understand?’

- ‘Are they attractive or unattractive?’

- ‘Are they cluttered?’

Chapter 3 and 4 examine use of graphics as a part of multimedia design in more detail, from those that decorative to those that are more directly illustrative, such as graphs. These can all be useful, and they can all be overused. Hence, the self-check questions remain useful when trying to assess whether your graphics are adding or subtracting from ease of understanding and the learning experience.

Accessibility

- Logical heading structures - use headings and subheadings sequentially

- White space - don't overcrowd content

- Alt-text for images (the description of an image)

- Clear colour contrast

- Closed captions and transcriptions for multimedia

Increasing accessibility by adopting accessibility features/or protocols can be kept in mind and added further down the microlearning design path.

Accessibility: universal design for learning (UDL)

Students expectations of design are increasing, expectations that courses follow good design logic, that they use frameworks such as universal design for learning (UDL), so that they are provided with a consistent and well-structured learning journey. Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) has identified a series of principles to guide design, development, and delivery in practice:

- Multiple means of engagement

- Multiple means of representation

- Multiple means of action and expression

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Examples

Multiple means of engagement

-

- Explicitly state learning goals and easy to relate to examples

- Give opportunities to celebrate

- Provide opportunities for discussion and reflection

Multiple means of representation

- Provide content in multiple ways: such as text, audio cast, video, e.g. short lecturer 'overview' videos, audio casts and diagrams, in addition to written text

Multiple means of action and expression

- Provide access to resources to deepen learning

- Interactive learning activity: all presentations and classes

- Include a variety of communication options

- Provide opportunities to review content or practice skills

Accessibility with modular design

Modular design is already a common practice convention in education where content for courses is segmented into units of learning called modules. Written content and instruction are organised by topics, similar in approach to chapter formatting in books. Modules contain key content and guide learners through sequenced learning resources including a<>ctivities. They are sometimes referred to as lecture notes. The importance of keeping content volume manageable, which is the topic of this chapter, cannot be overstated. It is something we need to keep working at. Volume ‘blow out’ is an ever-looming risk. It pays to keep more is less in mind, always.

Based on my observations, it has been common to segment courses into about five modules where students study individual modules over two or three weeks. Segmenting modules into week-by-week units of learning is better. It provides greater clarity and consistency in contain units of learning and volume.

Keeping modules as short as possible, a two-to-five-page range is best where practical. Remember, the goal in microlearning design is to increase engagement by increasing appeal. To increase the likelihood of students reading modules and materials with the appeal of conciseness and ease of reading load.

Conclusion

Volume overload, and perceptions of high volume (volume shock) are at the forefront of reasons why learners find learning, and the prospect of learning, overwhelming, and as a result unappealing.

Microlearning content reduction seeks to address cognitive overload and the stress it brings by reducing volume to make study more manageable, appealing and relevant.

Reducing volume involves retaining content based on relevance and practical value for (1) work and employability and (2) successful completion of assessments to support and increase success in study - as ways to keep learners interested and motivated in their learning. Further reducing volume involves decluttering by removing overly long or complex explanations. Clear and direct 'to-the-point' communication of information plays an important role in reducing cognitive load.

Packaging content in smaller, more manageable chunks, makes learning less demanding and as a result more accessible, and helps alleviate the pressures of the high-volume information world and competing lifeload demands facing many learners today.

Key points

Reduce volume: select/retain content on relevance and practical value, based on:

- equipping students to meet industry needs (industry alignment)

- equipping students for success in assessments

Drawing on constructive alignment to ensure alignment with clear and well-focused learning objectives, that are consistent with the design of course content, practice learning activities and assessments.

Relevance linking frequent highlighting of benefits of content and skills being developed. This is an important strategy for attracting student engagement and learning effectiveness.

Decluttering: to further reduce cognitive load and increase engagement

- Streamlining of content with modular design - by segmenting content into manageable modules

- Review and aim for ease of readability and understanding with direct, clear, concise and focused materials

- Simplify explanations and remove unnecessary words

- Review and aim for optimum balance with text and visuals, including presentation-slides

Reducing and refining content and ensuring alignment and relevance and practical value, enhances information assimilation, it provides both educators and learners with a route to enhanced educational experiences.

List of References

Alias, N. F., & Razak, R. A. (2024). Revolutionizing learning in the digital age: A systematic literature review of microlearning strategies. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2024.2331638

Biggs, J.B., & Tang, C. S. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Society for Research into Higher Education.

Bridgstock, R. (2009). The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 31-44.

Chan, C.K., Fong, E.T., Luk, L.Y., & Ho, R. (2017). A review of literature on challenges in the development and implementation of generic competencies in higher education curriculum. International Journal of Educational Development, 57(1), 1-10.

Chamorro-Atalaya, O., Flores-Velásquez, C.H., Olivares-Zegarra, S., Dávila-Ignacio, C., Flores-Cáceres, R., Arévalo-Tuesta, J.A., Cruz-Telada, Y., & Suarez-Bazalar, R., (2024). Microlearning and nanolearning in higher education: A bibliometric review to identify thematic prevalence in the COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic context. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 23(4), 279-297. https://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter/article/view/10025

Eggensperger, J., & Salvatore J. (2022). Strategic public relations writing proven tactics and techniques. Routledge.

Johnston, J., & Glenny, L. (2021). Strategic communication: Public relations at work. Routledge.

Kamel, O.M. (2018). Academic overload, self-efficacy and perceived social support as predictors of academic adjustment among first year university students. International Journal of Psycho-Educational Sciences, 7(1), 86-93. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED585260.pdf

Kapp, K.M., & Defelice, R.A. (2019). Microlearning: Short and Sweet. Association for Talent Development.

Kossen, C., (2022). Podcast: Communicating for Success, Episode 4, Transferable & professional knowledge & skills. https://www.podbean.com/ew/pb-imbup-13374ce

Kossen, C., Howard, M., Luke, J., & Hammermeister, K. [in press] (2025). Embedding career and employability curriculum in public relations: preliminary results, Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal, 27.

Lovell, O. (2020). Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory in Action. John Catt Educational Ltd. Melton, Woodbridge, UK.

Macnamara, J. (2018). Competence, competencies and/or capabilities for public communication? A public sector study. Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal, 19, 16-40.

Mahoney, J. (2017). Public relations writing. Oxford University Press.

Malik, P., & Garg, P. (2020). Learning organization and work engagement: The mediating role of employee resilience. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(8), 1071-1094. DOI: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1396549

Olesen, K.B., Christensen, M.K., & O'Neill, L.D., (2021). What do we mean by “transferable skills”? A literature review of how the concept is conceptualized in undergraduate health sciences education. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 11(3), 616-634. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-01-2020-0012

Pennington, A., & Stanford, J. (2019). The future of work for Australian graduates: The changing landscape of university-employment transitions in Australia. The Centre for Future Work, Australia Institute. https://futurework.org.au/report/the-future-of-work-for-australian-graduates/

Quacquarelli Symonds (QS). (2019) Graduate employability in Australia: Bridging the graduate skills gap. https://www.qs.com/portfolio-items/graduate-employability-in-australia-bridging-the-graduate-skills-gap/

Schoenmaker, S., & Erskine, V. (2019). Understanding practitioner resilience in public relations. Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal, 21, 1-19.

Smith, R. (2022). Becoming a public relations writer: Strategic writing for emerging and established media. (6th ed.).Routledge.

Suleman, F. (2018). The employability skills of higher education graduates: Insights into conceptual frameworks and methodological options. Higher Education, 76(2), 263-278. doi: 10.1007/s10734-017-0207-0

Sweller, J. (2010). Cognitive load theory: Recent theoretical advances. In J.L. Plass, R. Moreno, & R. Brünken (Eds), Cognitive Load Theory (pp. 29-47). Cambridge University Press.

Torgerson, C. (2021). What is microlearning? Origin, definitions and applications. In J.R. Corbeil, B.H. Khan, & M.E. Corbeil (Eds.), Microlearning in the digital age: The design and delivery of learning in snippets (pp. 14.-31) Routledge.

Wijaya, T.T., Cao, Y., Weinhandl, R., Yusron, E., & Lavicza, Z. (2022). Applying the UTAUT Model to understand factors affecting micro-lecture usage by mathematics teachers in China. Mathematics, 10(16), doi.org/10.3390/math10071008

World Economic Forum. (2018). The future of jobs report 2018. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2018.pdf

Attributions

Kossen, C. 'Episode 4, Ch 1 Pt 3: Transferable & professional knowledge & skills', Communicating for success [podcast].

Kossen, C., Howard, M., Luke, J., Hammermeister. School of Humanities & Communication: Improving the employability outcomes for PR students CC-BY-4

Media Attributions

- Learning Objectives © Chris Kossen is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Icons for microlearning © The Noun Project is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license