5 Commemorating Genocide Holocaust Memorials in Australia and Overseas

Introduction

On Australia Day 2021 Federal Treasurer and Liberal Member for Kooyong (a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria), Josh Frydenberg, and Labor Member for Macnamara (also in Melbourne, Victoria), Josh Burns wrote an opinion piece in the Sydney Morning Herald that acknowledged an interesting turn in Australian commemorative practices. As Frydenberg and Burns (2021, para. 14) noted, the establishment of Holocaust museums promoted tolerance and ‘understanding while combating racism and anti-Semitism’. This drive for Holocaust commemoration will eventually see Holocaust memorials and museums established in each capital city. These initiatives are occurring concurrently with the controversial $500 million expansion of the Australian War Memorial, concern over what some see as the paucity of funding allotted to the National Archives, and the ongoing debate about the Frontier Wars and the traditional narrative of European settlement as a benign and civilising process.

Both Frydenberg and Burns lost family members during the Holocaust, a connection that gives them a very personal stake in the delivery of Holocaust education in Australian schools, as well as via its cultural institutions. They see this as a means of ensuring ‘the children of today and tomorrow learn from the past and work towards a brighter, more tolerant and inclusive future’ (Frydenberg & Burns, 2021, para. 16). Both Frydenberg and Burns (2021, para. 1) seek to position the Holocaust as a specific event, one that was ‘not just a crime committed against the Jewish people [but also] a crime against humanity’. They have sought to add to this specificity broad links to contemporary Australian political and cultural values, including ‘a deep commitment to multiculturalism and diversity’ and ‘a pride in the many cultures, religions and identities that make up Australia’ (Frydenberg & Burns, 2021, paras. 25-26).

The determination to ensure the Holocaust does not fade from the collective memory as the last survivors pass away was backed by considerable financial support. In August 2020 the state government of Western Australia allocated $6 million to help fund the construction of a new Jewish Community Centre in Yokine, a suburb of Perth, which would include a Holocaust education centre. In late September 2020 the Morrison Government announced funding of $3.5 million to support the establishment of a Holocaust Museum and Education Centre in Brisbane, Queensland. The then Minister for Education Dan Tehan (2020, para. 3) argued that ‘It is critical that people of all ages, and particularly our young people, learn about this dark period in world history’. Given his role in education, he unsurprisingly harboured hopes for the didactic value of a museum for it ‘would ensure generations of Queenslanders can learn about the past to prevent discrimination and prejudice in the future’ (Tehan, 2020, para. 5).

In October Tehan announced that $2.5 million of government funding would be likewise directed to the establishment of the Adelaide Holocaust Museum and Steiner Education Centre in Adelaide, South Australia. In January 2021 Alan Tudge, the Minister for Education and Youth, and Andrew Barr, the Australian Capital Territory Chief Minister added $750,000 to the growing total to assist in establishing the Canberra Holocaust Museum and Education Centre in the nation’s capital. In March 2021 the Australian Government committed $2 million towards the establishment of a Holocaust education centre in Hobart, Tasmania, in a move that angered some Aboriginal activists, who argue that ‘history much closer to home was being ignored’ (Cooper, 2021, para. 3). The Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) was founded in Elsternwick, a suburb of Melbourne, Victoria in 1984 by Holocaust survivors. The Sydney Jewish Museum was established in 1992 by the generation of Holocaust survivors who migrated to Australia, and now with the announcement of other Holocaust education centres in other states and territories in Australia the ring had now been closed.

Though each centre will probably include a memorial to the Holocaust, there are nevertheless some, though not many, already in existence. Western Australia has the Holocaust Memorial (1995) in Perth. Victoria has the Jewish Victims of the Holocaust (2008) in Melbourne. The Leo Baeck Centre for Progressive Judaism at Kew, Melbourne, has a striking modern wind sculpture entitled ‘… and the wind whispered your name’ (2010). New South Wales has the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Holocaust Memorial (2001), three memorials at The Sydney Jewish Museum – the Sanctum of Remembrance (1992), The Children’s Memorial (2002) which commemorates the 1.5 million children who were murdered during the Holocaust, and the Zachor (‘Remember’) Digital Memorial (2017) which is part of ‘The Holocaust and Human Rights’ exhibition – and the Paul and Eva Lederer Youth Campus and Art Garden (2019) at the Central Synagogue, also in Sydney.

In her keynote speech at the Holocaust Memorial Dedication Service at the Leo Baeck Centre for Progressive Judaism on November 14 2010, Pauline Rockman OAM, President of the Jewish Holocaust Centre argued that the most successful memorials allow for a multiplicity of interactions and rituals and which encouraged reflection and dialogue (Rockman, 2010).

What was the Holocaust?

The Holocaust refers to the systematic, state-sponsored murder of six million Jews by Nazi Germany and it collaborators. Though it drew on older anti-Semitic beliefs, it was implemented in stages after the Nazis came to power in 1933. It started with anti-Jewish legislation and economic boycotts, escalating to mass killings, and finally to genocide after the start of the Second World War in 1939. In all, two thirds of European Jews were murdered in a process referred to euphemistically by the Germans as the ‘Final Solution to the Jewish Question’. Though some conspiracy theorists deny that the Holocaust occurred or argue that the numbers are exaggerated, the proof that a systematic and widespread attempt to annihilate the Jewish people is both extensive and compelling.

Resources

Yad Vashem. The World Holocaust Remembrance Center. (n.d.). Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center. Yad Vashem. The World Holocaust Remembrance Center. https://www.yadvashem.org/

Video 5.1: The Holocaust

Transcript available from Khan Academy

Video 5.2: The path to Nazi genocide

Commemorating the Holocaust

Most of the Holocaust museums and memorials constructed around the world since 1945 are driven either by either nationalistic or humanistic imperatives. The former connects the Holocaust to the broader history of the nation in which it is located. The moral, political and social implications are then often used as a vehicle to explore contemporary political issues. The latter approach is informed by the value of ‘the universal humanistic lessons of the Holocaust’ as an element in the ‘fight against prejudice, discrimination and racism’ (Berman, 2006, pp. 34-35). The Australian government’s approach is a hybrid, with politicians particularly open to links with contemporary Australia. The specific Jewish experience is sometimes dehistoricised and replaced by a vision of the Holocaust as an example of the destruction wrought by all forms of racism and intolerance (Alba, 2007, p. 151). The relativising of the Holocaust positions it as a ‘cosmopolitan memory’ (Levy & Sznaider, 2002, p. 88), a ‘traumatic event for all of humankind’ (Alexander, 2002, p. 6), and the ‘archetypal sacred-evil of our time’ (Moses, 2003, p. 6).

Designers of Holocaust memorials have to confront the tension between aesthetic imperatives and the ethical considerations inherent in the memorialisation of an event that many consider beyond comprehension. James Ingo Freed, the designer of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, initially had doubts that it was even possible to address the aesthetic issues of engaging with an ‘unimaginable, unspeakable, and un-representable horror’ (Young, 1993, p. 16). As Freed (1993, p. 89) conceded, ‘looking over your shoulder, you were always aware of the spectre of this thing, those millions of bodies’. In effect, he knew he would need to engineer a monument that would evoke a nightmare (Argiris, Namdar, & Adams, 1992, p. 48). As Bewes (1997, p. 145) observes, Auschwitz is an affront to human rationality. Any attempt to depict it must find a way to do so and ‘not … insult the millions of real dead’ (Lyotad, 1989, p. 364). From the earliest attempt to memorialise the Holocaust in 1943 at the Majdanek Concentration Camp near Lublin, Poland, to the most recent efforts, three characteristics have come to dominate these attempts:

- they are addressed to transnational audiences

- they communicate multiple meanings

- they use a new repertoire of symbols, forms and materials to explore those meanings

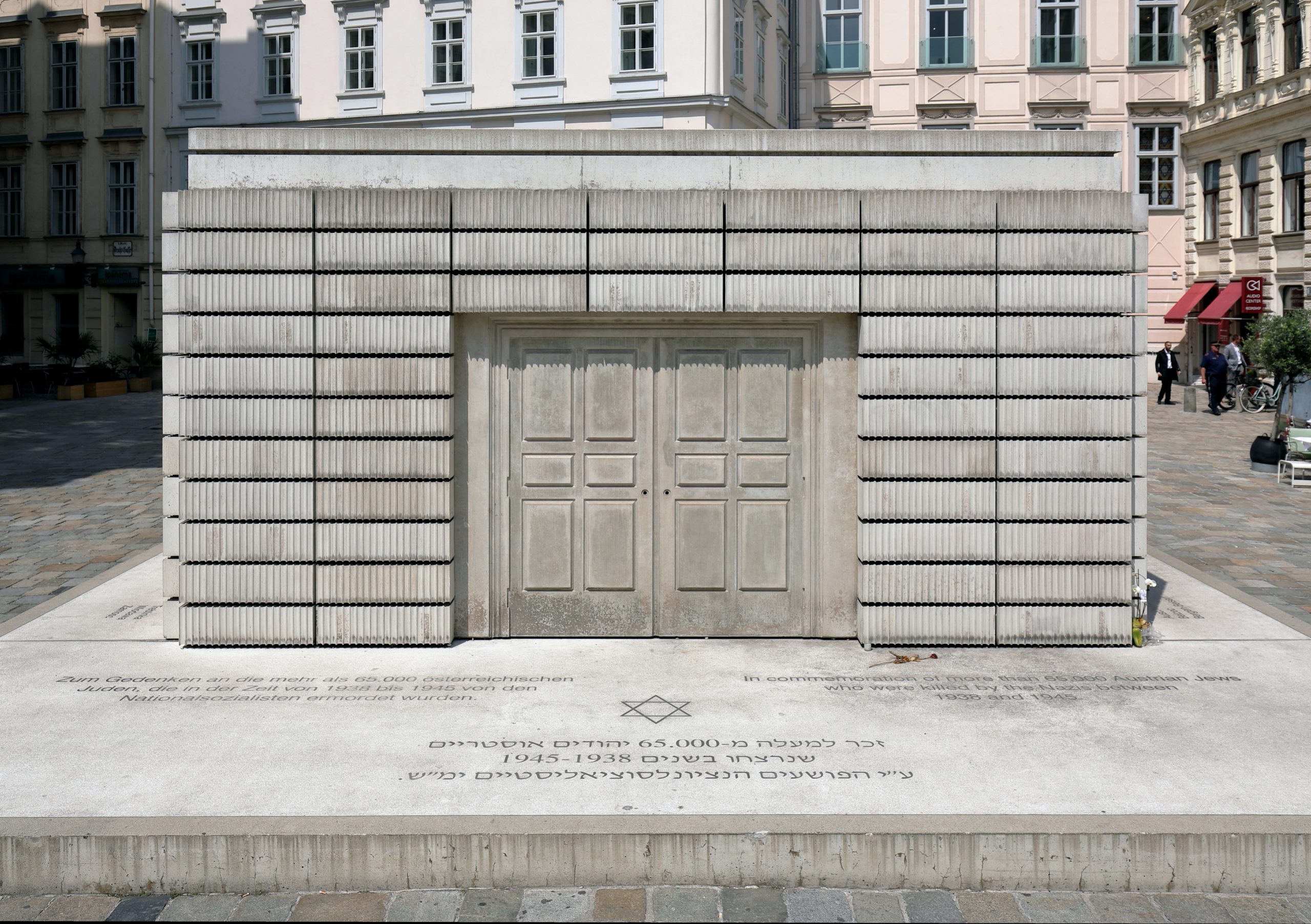

Having dispensed with the use of stelae (slabs or pillars), towers and realistic statuary by the 1960s, Holocaust memorials no longer resembled traditional war memorials of the type familiar to most Australians. Holocaust memorials and monuments therefore tend to adopt larger, more expansive, abstract and avante-garde forms (Marcuse, 1978) (See Figures 5.2 and Figures 5.4–6). Figurative references are less visible – for example Figure 5.2 does contain human forms, but they have been transformed into barbed wire. In Figure 5.3 the people have been more realistically presented, but as noted this is not common practice in Holocaust memorial and monument design due to the complexities of presenting such an horrific event.

Video 5.3: Architecture of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe

Video 5.4: Inside Auschwitz – English version in 360°/VR

Video 5.5: The world’s first Holocaust museum

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Ui9pBBNSKN0

Video 5.6: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Video 5.7: Holocaust Memorial in Miami Beach, Florida

Discussion questions

View the 10 shortlisted designs for London’s Holocaust memorial.

- Do they have anything in common?

- What are the differences between the designs?

- Which one do you prefer? Why?

View the winning design in this video:

Video 5.8: Holocaust Memorial in Westminister

- Was it a design you liked?

- Why or why not?

- Would you visit the memorial?

- Would you feel comfortable taking a ‘selfie’ at the memorial? Why? Why not?

Activity

Think about how you would design a Holocaust memorial in your local area.

- Would you use an abstract design?

- What symbols might you include?

- Would materials would you use?

- Would you include text or figurative elements?

References

Alba, A. (2007). Displaying the sacred: Australian Holocaust memorials in public life. Holocaust Studies, 13(2-3), 151-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2007.11087202

Alexander, J. (2002). On the social construction of moral universals: The ‘Holocaust’ from war crime to trauma drama. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(1), 5–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431002005001001

Argiris, L., Namdar, K., & Adams, T. (1992). Engineering a monument, evoking a nightmare. Civil Engineering, 62(2), 48-51.

Berman, J. E. (2006). Holocaust agendas: Conspiracies and industries? Issues and debates in Holocaust memorialization. Vallentine Mitchell.

Bewes, T. (1997). Cynicism and postmodernity. Verso.

Cooper, E. (2021, 4 March). Tasmanian Aboriginal community hurt by lack of memorial, says government ‘ignores’ bloody history. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-04/tasmanian-aboriginals-holocaust-centre/13214986

Freed, J. I. (1993). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. In J. E. Young (Ed.), The art of memory: Holocaust memorials in history (pp. 89-101). Prestel-Verlag.

Frydenberg, J. & Burns, J. (2021, 26 January). Learning from a tragic past to build a better future. Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/learning-from-a-tragic-past-to-build-a-better-future-20210126-p56wu7.html

Levy, D. & Sznaider, N. (2002). Memory unbound: The Holocaust and the formation of cosmopolitan memory. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(1), 87-106. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1368431002005001002

Lyotard, J. F. (1989). Discussions, or phrasing ‘After Auschwitz’. In A. Benjamin (Ed.), The Lyotard Reader (pp. 360–392). Blackwell.

Marcuse, H. (1978). The aesthetic dimension: Towards a critique of Marxist aesthetics. Beacon Press.

Moses, D. (2003). Genocide and Holocaust Consciousness in Australia. History Compass 1(1), 1- 13. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1478-0542.028

Rockman, P. (2010, Nov 14). Holocaust Memorial Dedication Service – Keynote speech. Leo Baeck Centre for Progressive Judaism. https://www.lbc.org.au/images/pdf/101114-pauline-rockma-keynote-speech-dedication-service-for-leo-baeck-centre.pdf

Tehan, D. (2020). New Holocaust Museum in Queensland. Ministers’ Media Centre, Department of Education, Skills, and Employment. https://ministers.dese.gov.au/new-holocaust-museum-in-queensland

Young, J. E. (1993). The art of memory: Holocaust memorials in history. In J. E. Young (Ed.), The art of memory: Holocaust memorials in history, (pp. 19-38). Prestel-Verlag.