3 War Memorials in the Australian Commemorative Landscape

Introduction

Before the First World War (1914-1918) Australia had very few civic monuments. The war memorials constructed after 1918 irrevocably changed the Australian commemorative landscape and in doing so they became the new Commonwealth’s first national monuments. By the mid nineties, well before the renewed construction associated with the war’s centenary, it was estimated there was one monument for every 30 soldiers killed. The comparable figure for France is one memorial for every 45 soldiers killed (Hedger, 1995). War memorials are far from being a uniquely Australian phenomenon – indeed, the first known example, the White Monument at Tal Banat, can be traced to Syria in the third millennium BC. Nevertheless, their domination of the commemorative landscape ensures they are an Australian icon, which makes their limited use in Australian schools even more bewildering. Educators do need to ensure, however, that their students understand that they are inherently ideological, usually offer a state sanctioned version of history, are indicative of the views of the generation that built them rather than the generation they commemorate, and that how they are ‘read’ can alter over time.

Traditional war memorials

During the first great wave of memorial building in the 1920s and 1930s, sculptors and designers used symbols that were familiar to most people. During this period commemoration often ‘reconciled triumphalism and sacrificialism within narratives of Australian heroism and achievement’ (Crotty & Melrose, 2007, p. 681). Your local war memorial may therefore include any of the following symbols:

- urns and broken columns as symbols for death

- wreaths for mourning, eternal light and torches for remembrance

- crosses for sacrifice

- the laurel

- triumphal arches

- Winged Victories for victory

- globes for mankind

- columns for honour

- lions for fortitude

- water and obelisks for regeneration

- rising suns for national birth.

These symbols of Edwardian classicism brought ‘together all that seemed best and most noble in the artistic life of the civilization they had fought to preserve’ (Borg, 1991, p. xii). Traditional war memorials were therefore not considered an appropriate forum for artistic experimentation and innovation and therefore usually confined themselves to symbolic forms that were familiar to Australians of the time.

If your town or suburb has a memorial that was built during the interwar years it is likely that it is either an obelisk, a stone monolith originating in ancient Egypt, or an Australian soldier or ‘digger’ with an upturned rifle. The obelisk is the most common form of war memorial, with Queensland the only state preferring this symbol instead of the soldier statue. The obelisk possessed certain advantages: it was nonsectarian, widely recognised as a symbol of death or glory, and for communities struggling to raise the necessary funds, it could also be easily and cheaply supplied (Inglis, 2008). The obelisk at Macquarie Place Park in Sydney was reputedly erected on the site where Governor Phillip raised the Union Jack in 1788. It is the earliest surviving public monument commemorating the colonisation of Australia (Figure 3.2).

Discussion questions

- What do Central Park in New York, the Embankment of the River Thames in London, the Place de la Concorde in Paris, Sultanahmet Square in Istanbul, and the Piazza San Pietro in Rome have in common?

Find out the answer. - What capital city has an obelisk that commemorates one of its ‘founding fathers’ and why have they used an ancient form of commemoration?

If your town or suburb’s memorial is not an obelisk, a pillar or column, it is probably a ‘digger’ statue. Although there are often numerous differences from one figure to the next, it is unlikely that they are in an aggressive posture. Unlike bronze, stone does not lend itself to imitating action, though the memorial in Atherton is a rare example (Figure 3.4). Many have the soldier figure standing with the rifle resting upside down in the funeral position (or ‘reverse arms’), as is the case with the memorial in Dalby, Queensland (Figure 3.1). Like the obelisk, the soldier statue is usually accompanied by a plaque bearing the names of all who served from the town or region – usually without rank – with a small cross or star indicating those who had ‘made the supreme sacrifice’.

Instead of statues and obelisks, some communities built a utilitarian memorial such as a community hall. Sixty percent of First World War memorials were monuments, while approximately twenty percent are halls, and between one and two are hospitals or schools, with eighteen percent being both functional and monumental (Inglis, 2008).

There are a range of other war memorial forms located across Australia. For example: a Doric Pavilion in Narrogin, Western Australia; a tower in Goulburn, New South Wales; a cenotaph in Gosford in New South Wales, and an Arch of Victory in Ballarat, Victoria. However, regardless of the type of war memorial your suburb or town has, or even if there is not one close enough to visit during school time, it would be a valuable exercise to discuss what kind of symbols and figures are not used on memorials constructed during the 1920s and 1930s.

The Maryborough War Memorial (Figure 3.6) is the only local First World War memorial that includes a Red Cross nurse (as well as figures of a soldier, sailor and airman) beneath a Winged Victory. There are also a few figures of allegorical females such as the ones in bronze in Wellington in New South Wales. The figure of Victory is flanked by History (right) and Fame (left). Clearly, however, the digger mythology was a masculine one, and the choice of memorials reflected that narrowness.

Not all memorials were intended for parks or other publics paces. Schools, workplaces and community halls also constructed memorials, often in the form of honour rolls. As these two examples show, construction began before the war was even over.

At the other end of the scale are the large state memorials located in the capital cities. Only two of the seven were completed by 1930, with the result that they were far too late to offer therapeutic comfort. As Inglis (2008, pp. 266-267) observes, however, that was never their primary purpose. They were instead ‘public declarations, acts of formal homage, involving everywhere the governments and parliaments which had collaborated to make soldiers of their citizens’. That did not mean they could not be beautiful. Brisbane’s Shrine of Remembrance (Figure 3.10) with the eternal flame burning at its heart, in the heritage-listed Anzac Square, is one of the country’s most beautiful classical Doric structures (Hedger, 1995). It was not just the classical architecture that communicated a message: the 18 columns represent the end of the First World War, as do the number of stairs leading up to the shrine itself – 19 in the first row and 18 in the second – which when combined signify the year of peace, 1918. The bottle (boab) trees in Anzac Square commemorate the Queensland Light Horse Regiments, which served in South Africa’s Boer War (1899–1902), while the Middle Eastern date palms symbolise Australia’s victories in the Middle East during both World Wars. To Christians, palms are also a biblical symbol of victory. At its base is a relief tableau by Daphne Mayo dedicated to fallen Queenslanders by the women of Queensland. The drinking fountains and the circular pools are symbolic of new life. The memorial is now surrounded by other statues commemorating later wars, though they are realistic rather than abstract in design.

Each of the other states also commissioned their own memorials, with Raynor Hoff’s memorial in Adelaide being particularly noteworthy. On the front is the Angel of Death presented here as a flattened stylised relief carving holding a sword over the altar of sacrifice and holding a laurel and a wreath:

‘He towers over a bronze figure group of ordinary people: a woman, a scholar and a farmer, who pay homage to the dead and who pleaded with the Angel from their subservient roles. The disregard of the angel heightens the impact and makes the work a symbol of despair’ (Hedger, 1995, p. 33).

On the obverse is the Angel of Resurrection, who bears a dead soldier away to eternal rest and glory while preparing to crown him with a victory laurel in a move that shifts the viewer from despair to hope. We see in the memorial Hoff’s interest in Art Deco which he later used in the ANZAC Memorial in Sydney (Figure 3.12).

The British Empire’s practice of not repatriating the dead of the First World War meant the term cenotaph became so emotionally charged that whatever the form of a memorial, it was really ‘first and last, an empty tomb’ (Inglis, 2008, p. 248).

The modern commemorative landscape

Rather than building additional obelisk, cenotaph or soldier memorials after the end of the Second World War in 1945, the addition of extra names to an established memorial plinth seemed a more practical solution. The postwar population boom and increased numbers of young people in need of healthy recreation led to the proliferation of swimming that served a commemorative purpose as well as meeting community needs at a time of post-Olympic fervour (McShane, 2009). The designers of contemporary Australian war memorials, however, are to a certain extent freed from the ‘artistic tyranny of the Anzac myth’ (Garton, 1996, p. 45). As a result, the heroic memorial has increasingly been replaced by a ‘new breed of abstract’ and, often, ‘therapeutic’ memorial’ (Stephens, 2012, p. 146). Some of the designers have chosen not to exercise this freedom, as was the case with the visually arresting but undeniably anachronistic Australian Boer War Memorial in Canberra (Figure 3.13).

Others have sought an uneasy accommodation between a style reminiscent of Great War memorials and abstraction (The Korean War Memorial, Canberra), or have used the Great War iconography augmented, but never challenged by the symbols of a marginalised group (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander War Memorial, Adelaide). Some use well known symbols not usually seen in Australian memorials which mount a muted challenge to hegemonic narratives but which are in reality seeking admission to them on the part of a marginalised group (Yininmadyemi – Thou didst let fall, Sydney).

Some designers have drawn inspiration from ancient standing stones or monoliths and classical stelae (slabs or pillars) to communicate a conservative narrative for a new class of war hero. For example, the Australian Peacekeeping Memorial in Canberra (Figure 3.17).

They have also been used to commemorate service in an unpopular cause – for example, the Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial (Figure 3.18) – which is an interesting example of the shift in memorial design:

The memorial includes a contemplative space, an addition that is typical of many similar efforts to confront a difficult past or which acknowledge a multiplicity of stories. The absence of the classical symbolism that pervades earlier Australian war memorials is marked, as is the foregrounding of trauma and suffering. This structure is not a celebration of the nation state and is instead dedicated to ‘all those that suffered and died’. As Stephens (2012, p. 149) observes, the inward facing stelae and the suspended stone halo are intended to produce a feeling of unease, so much so that he describes the structure as a ‘pensive and anxious memorial’.

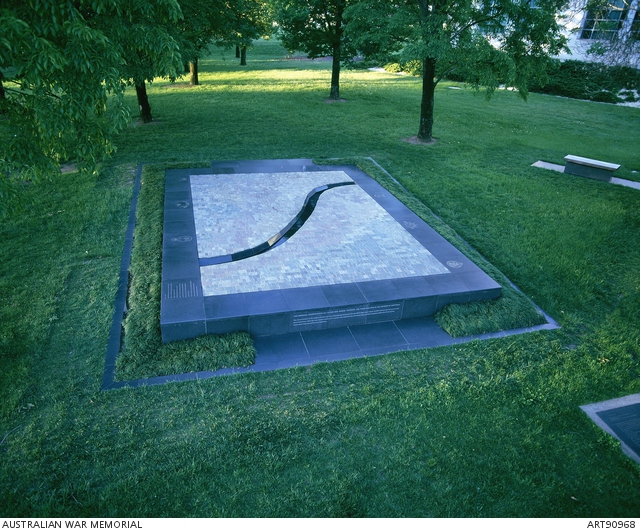

As Australian society has changed markedly over the years since 1918, memorials need to tell a different story, one that is symbolically authentic (Stephens, 2012). The question of what is authentic is inevitably contested. An example of the difficulty of employing an artistic language that ‘speaks’ to such a diverse society is evident in the Korean War Memorial in Sydney (Figure 3.14). When it was unveiled in 2010, some people saw it as a ‘welcome departure’ from the ‘heroic monumentality of traditional Australian war memorials’ (Ward, 2010, p. 56). For people more familiar with traditional war memorials, the shift to abstraction is not as welcome as Ward’s observation might suggest, as Anne Ferguson found to her cost when designing the Australian Servicewomen’s Memorial in Canberra (Figure 3.19). Her flat, abstract design aroused significant controversy. As Sebastian Smee (2000, p. 371) observed, publicly commissioned sculptures disappoint people as there are many ideas from different stakeholders and the end result never matches their expectations expectations. Clearly there are still ‘tensions between traditional memorial design and the current transition in Australia towards memorials that are more overtly abstract and interactive’ (Stephens, 2012 p. 142).

Despite the plethora of war memorials and their often singular narratives, there is a growing awareness of the need to include marginalised voices whose experiences have been excluded from official commemoration. One of the most effective is the Aboriginal Memorial at the National Gallery of Australia (Figure 3.20), completed in 1988 for the bicentenary. It is an installation of 200 hollow log coffins from Central Arnhem Land, one for each year of European occupation. The logs are, like cenotaphs, empty tombs which commemorate people who have died defending their land, though in this case they fought against, rather than for, white Australia.

Activity

Create a visual timeline which includes six Australian war memorials from the following conflicts:

- Frontier Wars (1788-1939)

- Boer War (1899-1902)

- First World War (1914-1918)

- Second World War (1939-1945)

- Korean War (1950-1953)

- Vietnam War (1955-1975)

Write a short paragraph for each image on the timeline which provides an overview of the conflict including the dates, locations, rationale for the conflict and result of the conflict. What differences and similarities can you see between the memorials over time?

Choose one of the Australian war memorials from your visual timeline and complete the following:

- Find another war memorial that commemorates the same conflict in another country – if choosing the Frontier Wars you might like to consider other memorials that explore battles between Indigenous peoples and colonising forces

- Consider the wording on the Australian and overseas memorial and discuss any similarities or differences between the text that has been used on both

- Take time to explore the design of both memorials and imagine you are a visitor at both sites

- Imagine you are a family member who lost someone in this conflict and in an email or short travel blog for your family, describe your reaction to both memorials and whether you believe they successfully capture the conflict that is being commemorated

The following sites may assist you with researching Australian memorials:

- Monument Australia – https://www.monumentaustralia.org.au/

- Places of Pride: The National Register of War Memorials – https://placesofpride.awm.gov.au/

- Queensland War Memorial Register – https://www.qldwarmemorials.com.au/

- Register of War Memorials in New South Wales – https://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/

- Victorian Heritage Register – https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/

References

Borg, A. (1991). War memorials from antiquity to the present. Leo Cooper.

Crotty, M. & Melrose, C. (2007). Anzac Day, Brisbane, Australia: Triumphalism, mourning and politics in interwar Commemoration. The Round Table 96(393), 679–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358530701634267

Garton, S. (1996). The cost of war: Australians return. Melbourne University Press.

Hedger, M. (1995). Public Sculpture in Australia. Craftsman.

Inglis, K.S., & Brazier, J. (2008). Sacred places: War memorials in the Australian landscape. Melbourne University Press.

McShane, I. (2009). The past and future of local swimming pools. Journal of Australian Studies, 33(2): 195-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050902883405

Smee, S. (2000). ‘Just a great big zero’: Anne Ferguson’s Australian Servicewomen’s Memorial in Canberra. Art + Australia, 37(3), 370-371.

Stephens, J. (2012). Recent directions in war memorial design. The International Journal of the Humanities 9(6), 141-152.

Ward, N. (2010, 1 May). Korean War Memorial. ArchitectureAU. https://architectureau.com/articles/korean-war-memorial/