6 An Education in Commemoration: The Australian Curriculum, Commemoration and Memorials

Reflection

Think back to your primary schooling, especially if you were educated in Australia. Do you remember starting the first week of school in January on a Wednesday, because the Australia Day public holiday on January 26 had disrupted the beginning of the school year? Do you remember learning about Captain Cook’s voyage in 1770 and the establishment of the first British colony in 1788? Do you remember standing in the undercover area on April 25 for Anzac Day as your principal introduced a representative from the local branch of the Returned and Services League of Australia (RSL), to speak about the sacrifices made at Gallipoli and elsewhere by Australian servicemen and women, and then hearing the school captain read the Ode of Rembrance followed by the playing of the Last Post? Perhaps your school sent a contingent to the Dawn Service held near an Anzac Memorial or you or your family members marched in the Anzac Day parade. Perhaps your school visited a local museum where you learnt about the struggles of the first European settlers. Did you learn about the history of your town or region and about prominent locals who distinguished themselves in politics, industry, sport or entertainment? You may have learnt about the Aboriginal communities who once lived locally, or perhaps even something about the Frontier Wars? You may even have travelled to Canberra where you probably visited the Australian War Memorial, Parliament House and the National Museum of Australia.

Introduction

As this reflection indicates, acts of commemoration are embedded into our educational system, not only as a part of the official History curriculum, but in the routines and rituals of the school year. These acts of commemoration play a significant role in shaping our understanding of local, regional and national history. The History Rationale in the Australian Curriculum states that ‘an awareness of history is an essential characteristic of any society, and historical knowledge is fundamental to understanding ourselves and others’. In addition, it is ‘interpretative by nature, promotes debate and encourages thinking about human values, including present and future challenges’ (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2021, para. 1). An important aspect of History is related to what societies – both past and present – choose to commemorate and how. There are various forms of commemoration which can include memorials or monuments that are usually permanent and occupy civic or public spaces. The placing of a statue or memorial is, in effect, a colonisation of space little different from planting a flag. What they commemorate, how they were constructed and the role they play during community rituals and ceremonies offers an invaluable insight into seemingly officially sanctioned versions of a community’s history.

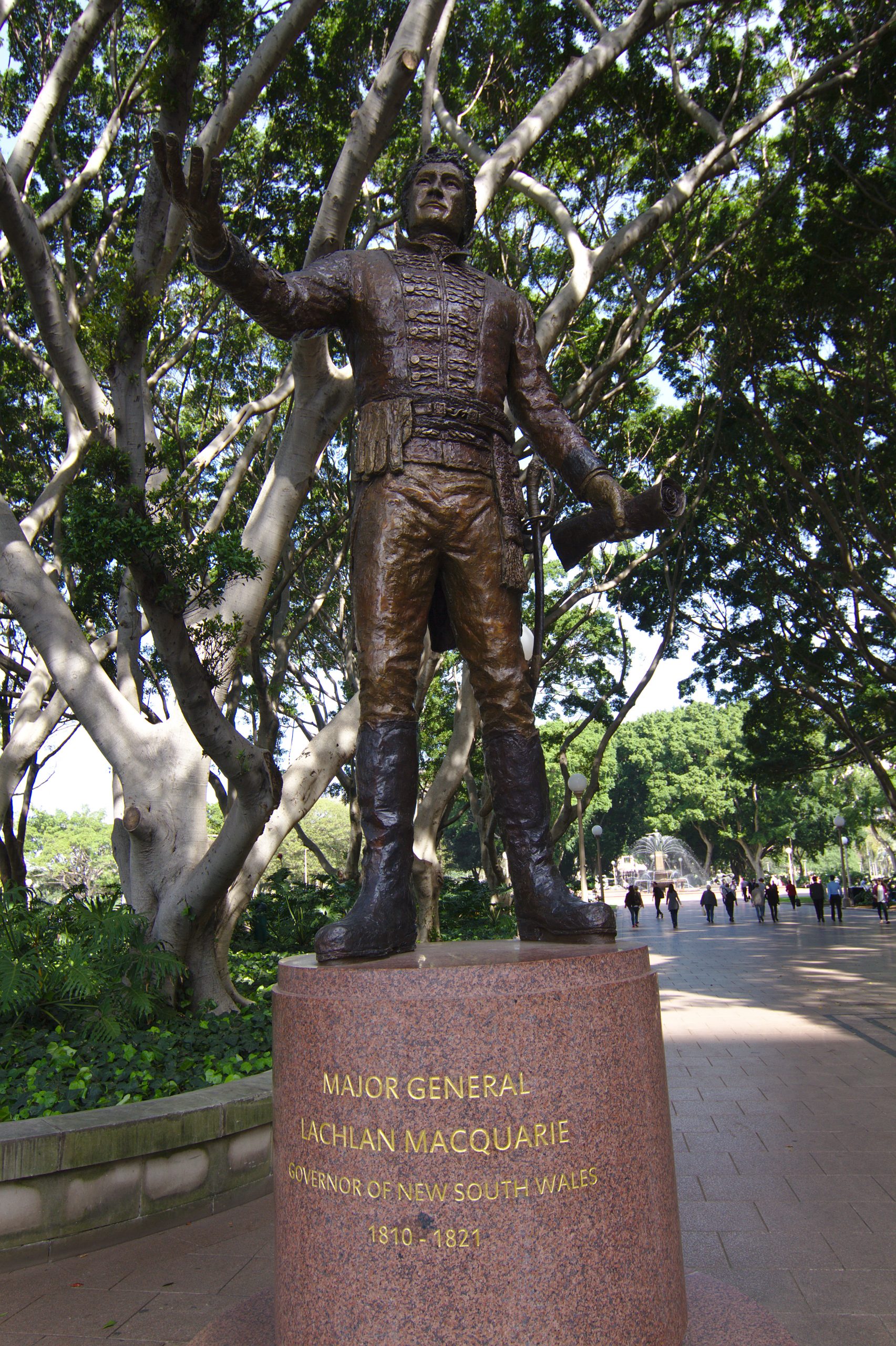

It is equally important to consider what is not commemorated – either in stone or during community ceremonies and celebrations – and to ascertain why these gaps and silences exist. Some statues and memorials commemorate European settlement in Australia, and they invariably offer what is, at best, an incomplete version of the past, as in the case of the statue to Governor Lachlan Macquarie at the beginning of this chapter. Sometimes, it is not just the history they tell that is incomplete. As Bruce Scates (2017, para. 2) observes, ‘By occupying civic space they serve to legitimise narratives of conquest and dispossession, arguably colonising minds in the same ways white “settlers” seized vast tracts of territory’. Some memorials and statues have been criticised because they sanitise a nation’s history by minimising or ignoring painful events. Sometimes a statue or memorial commemorates a person or event no longer considered appropriate – in these cases they are often toppled or damaged as we have recently seen through the Black Lives Matter (BLM) global movement (Fortin, 2017; Modhin & Storer, 2021). Our understanding of history evolves over time. Memorials and statues are, however, literally set in stone. They can be removed, vandalised, fall into disrepair or just be ignored if they no longer seem relevant to modern audiences.

Although users of this textbook may well teach in different countries, this section will provide a series of examples related to the Australian Curriculum: History in order to explore how memorials and monuments can be used to facilitate authentic learning experiences. Before introducing the Australian Curriculum: History, it is important to acknowledge the danger of engaging uncritically with memorials and monuments. As they are tangible objects which often have a nation building agenda – indeed, they often compel the viewer to physically look upward at them – they can be mistaken for history rather than versions of history.

The approach adopted by students when dealing with historical sources in the classroom needs to be replicated outside of it. That is not to say they are not a valuable insight into how particular ideas have developed and are maintained. It is just that they need to be used and critiqued with caution. For example, the majority of Confederate monuments in the United States were built during the era of Jim Crow laws – state and local laws that enforced racial segregation from 1877 to 1964. They may therefore prove to be a more accurate representation of the views of some Southerners during the period they were constructed rather than during the Civil War. In addition, as they are usually sited in public spaces, they represent an officially endorsed version of history – an important distinction. By critiquing memorials as they would any resource, educators will also discover that there are numerous opportunities to develop their pedagogy and to make acts of commemoration more meaningful and purposeful without drawing on the financial resources of the history department or school. It might be as simple as accessing photographs of memorials related to the period of history being studied.

Activity

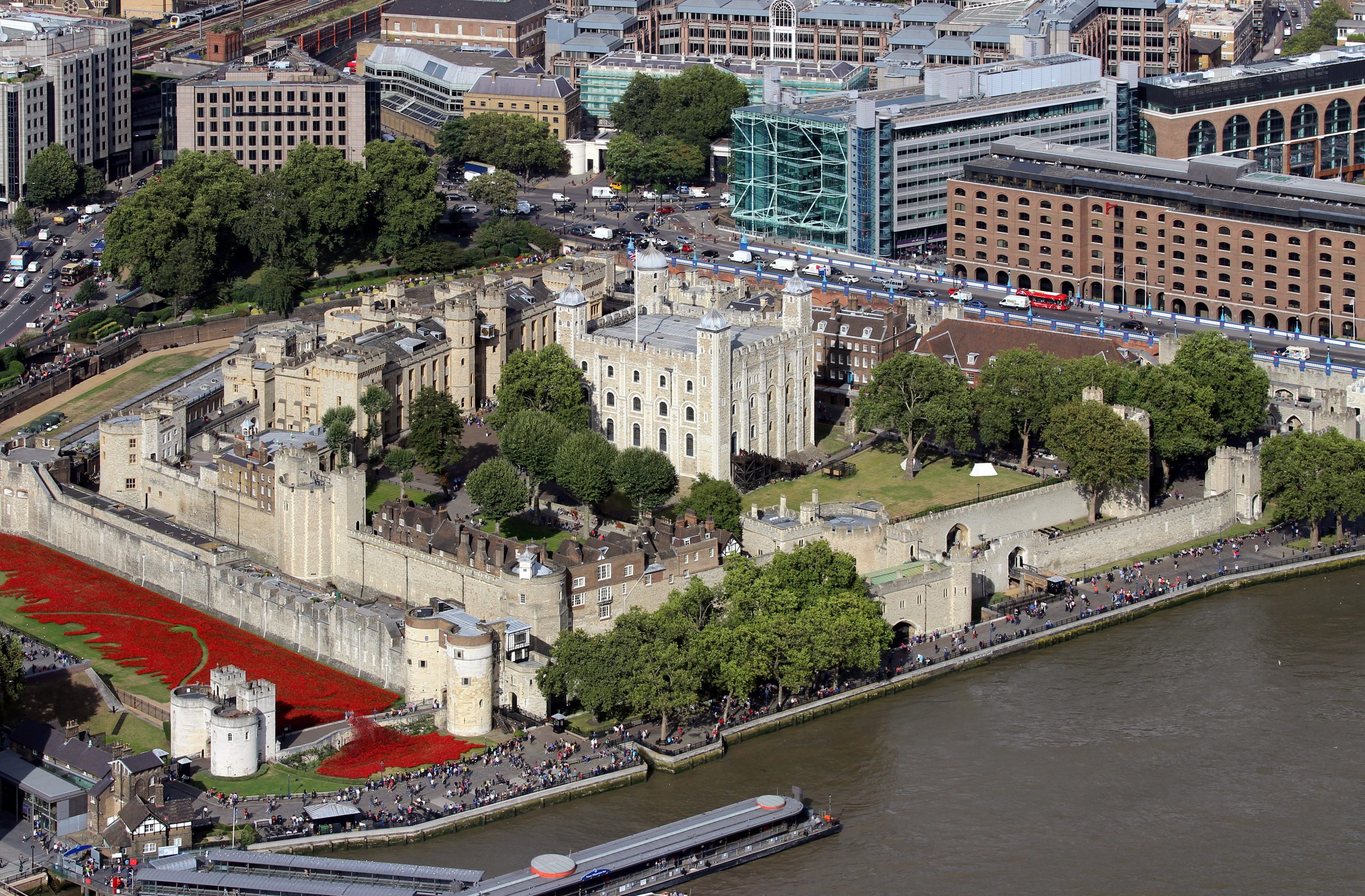

Look at the following images of a range of memorials and monuments related to war (Figure 6.2-6.13). Consider the similarities, the differences, the artistic choices and how they impact on the message that the memorial or monument communicates to viewers. Conduct some research into the events they commemorate and when they were built.

- What do they tell us about how these conflicts are remembered?

- What lessons are we as contemporary viewers likely to take away from seeing the memorials?

- What kind of emotional responses are likely to be generated?

The modern memorial

With the advent of modern architecture and its commitment to material and formal honesty came the prominence of the minimalist memorial – designs of commemoration that favored the absorbent meaning of abstract forms to the prescriptive qualities of literal sculptures. After Maya Lin sliced the ground on the National Mall to create the black granite wound of the Vietnam War Memorial and Peter Eisenman raised disorienting stelae out of Berlin’s fraught urban space to form the Monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe, many recent memorial designs have taken similarly understated routes, suggesting in a combination of both allusive and unspecific forms the shapeshifting nature of collective memory.

Sorabjee (n.d.) acknowledges that regardless of whether they are pervaded by a sense of reverence or a recognition of trauma, or whether they commemorate individual tragedy or mass conflict, memorials share a common motivation. They reflect a community’s desire to ‘pinpoint the collective memory in a shared physical experience, a space of reflection designed to hold the heaviness of history’. When they are controversial, either aesthetically or ideologically, she argued that the language of abstraction best allows ‘flecks of individual remembrance to colour in their volumetric outlines’.

Engaging with memorials and monuments

Engaging with memorials and commemorative activities will nevertheless compel educators to confront the intersection between history and myth. Historical myths should never be dismissed as mere fabrications or lies waiting to be exposed. They are foundational narratives through which people find their most important meanings. They are sacred and have over time passed into and become history (Mali, 2003, p. xii). They can have elements of truth (Robin Hood), they can be adaptations of stories and myths from other cultures (St Nicholas), they can be updated from generation to generation (King Arthur), they can embellished in literature (Paul Revere), they can be used for nation building agendas (the ‘Miracle of Dunkirk’) or they can be propaganda creations (The Angel of Mons). Each of these examples are grounded in historical events, but they have become part history, part sacred story.

Discussion questions

- What myths are you familiar with?

- Where did you first hear them?

- Do they serve a purpose other than entertainment?

- What do they tell you about the society that created them?

Research one of the examples provided and explore the ‘truth’ of the person or event versus the myth.

Mythology as pop culture

Ten reasons why Disney movies Are modern mythology

Heroes and superheroes: From myth to the American comic book

The Australian Curriculum: Humanities and Social Sciences (Foundation – Year 6) – History (Years 7 -10)

The table below summarises the Australian History topics across the F-10 Australian Curriculum, drawing upon the Humanities and Social Sciences – History strand (F-6) and then the dedicated History curriculum for Years 7-10. Note that not all of these topics are compulsory, for example in Year 10 schools choose from ONE of Migration, Popular culture or The Environment Movement. The topics below are those related to the use of local history in the classroom.

| Year Level | Topic | Content Descriptors |

| Foundation | HASS – History |

|

| Year 2 | HASS – History |

|

| Year 3 | HASS – History |

|

| Year 4 | HASS – History |

|

| Year 5 | HASS – History |

|

| Year 6 | HASS – History |

|

| Year 7 | Investigating the ancient past |

|

| Year 8 |

|

|

| Year 9 | Movements of Peoples |

|

| Year 9 | Making a Nation |

|

| Year 9 | World War I |

|

| Year 10 | World War II |

|

| Migration |

|

|

| Rights and Freedoms |

|

|

| Popular Culture |

|

|

| Environment Movement |

|

|

Although a teacher of history devoted to improving their craft is always able to search for opportunities to employ a creative and innovative pedagogy, the Australian Curriculum: History does not always lend itself to the integration of local histories. Yet, the opportunities are there for teachers willing to explore them. Indeed, research conducted by Anna Clark (2016) confirms that:

‘… the historical contradiction that sees intimate and personal histories generating genuine, tangible engagement … while official histories frequently struggle for relevance and attachment in the community more broadly. Look a little closer, and that paradox seems to hinge precisely on participants’ relationship to history – in particular, how it pertains to them, and whether they can see themselves in it’.

Case study

Most schools hold an ANZAC Day ceremony. Remembrance Day is also observed, with a one minute silence at 11 am on November 11, but ANZAC Day, with its public holiday, still stands out as the most significant commemoration of Australia’s service in various international conflicts. Schools also often play a role in community commemoration events – such as Dawn Services – by sending student leaders to lay a wreath or play another role in the ceremony. There have been a number of reasons posited for Anzac Day’s longevity: an increasing interest in family and community history (Holbrook, 2014), its appeal as a civic religion (Inglis, 2008) or as an expression of displaced Christianity (Billings, 2015), its status as a sacred parable above criticism (McKenna, 2007), an expression of the commerce and politics of nationalism (McKenna & Ward, 2007), the impact of a grand narrative that emphasises the role of Australian military engagements and the Anzac spirit in shaping the nation (Lake, 2010) and proof of a hunger for meaning, a craving for ritual and a search for transcendence (Scates, 2006).

Though each of these no doubt exerts at least some influence on how the April 25 is celebrated, it must be remembered that Australia’s wartime mythology – and by extension Anzac Day – has not remained static in the public imagination. Such was the growing disconnect from both the historical events and the rhetoric surrounding them that by the 1960s, Anzac Day was in terminal decline, a situation exacerbated by the growing opposition to the Vietnam War (Inglis, 1965):

Many of those who fought in the First World War were born in the last two decades of the nineteenth century when it was treated as a matter of faith that the sun would indeed never set on the British Empire. In contrast, the Australians who reached adulthood in the 1950s and 1960s inhabited a different world – one in which the social and moral values of their parents and grandparents appeared irrelevant. The British Empire was dissolving, the emotional link to the UK was at odds with an increasingly multicultural Australia, and the pre-eminence of the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in the national story appeared less certain than it had even a few years before (Rhoden, 2012).

The emergence of the construct of a ‘kinder, gentler Anzac’ in the late 1960s and 1970s transformed the Australian wartime mythology from one ‘grounded in beliefs about racial identity and martial capacity to a legend that speaks in the modern idiom of trauma, suffering and empathy’. In doing so, it ‘saved the Anzac legend from oblivion’ (Holbrook, 2016, p. 19):

‘In the post-Cold War and post-Vietnam era, war texts relating war’s disruption of civilisation grew in critical and popular regard … Our cultural values have evolved, bringing a consequent change in the valuation of war texts. From the 1960s, the emphasis shifted to exposing war in its guise of the antithesis of civilisation. War became no longer foundational but contradictory to civilisation, war being the ruination of society’ (Rhoden, 2012).

The annual Anzac Day parade on April 25 and the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra – which enjoys significant bipartisan political support – exert an almost unrivalled influence on the Australian understanding of the war specifically, and national identity more generally. To a modern audience ‘saturated with traumatic memories and understandings of victimhood’, this evolution in the understanding of Anzac Day conforms to a wider construct of history that increasingly characterises it as a ‘wound or scar that leaves a trace on a nation’s soul’ (Twomey, 2015, para. 17).

The explicit teaching of why we observe Anzac Day is important. The Australian War Memorial states ‘On Anzac Day we come together, in person and in spirit, to commemorate the men and women who have served our nation in all wars, conflicts and peacekeeping operations’ (Australian War Memorial, 2021, para. 1). The recognition that the rights and freedoms we enjoy today are in part because of the military service of Australian men and women, both in the past and today helps students understand the significance of Anzac Day. Incorporating a study of local ANZAC and war memorials into the curriculum – e.g. the Year 9 World War I unit is often taught at the end of the year, around Remembrance Day, and the Year 10 World War II unit often finishes at the end of Term 1, as ANZAC Day approaches – again helps make these connections to the students’ own lives more tangible.

This approach could include an investigation of what the memorial commemorates and what role it plays in the various rituals of community life. It is also important that a range of perspectives is considered:

- Who is not commemorated?

- Is there recognition of the service of women on the home front?

- Is there recognition of Indigenous servicemen and servicewomen?

- Are the less noble aspects of war or actions of individuals acknowledged?

By undertaking research on an aspect of local involvement in war, students come to have deeper and more nuanced understanding of not only the national narrative of ‘ANZAC-ery’, but also the real life ramifications war has on both service personnel, their families and their communities.

Schools are a key site for the building of national identity. In Australia, schooling is compulsory and the Foundation – Year 10 curriculum is a national one – even though it is addressed differently in different jurisdictions and contexts, it nonetheless provides the foundations for a commonality of learning experiences. This means the majority of Australian students have a similar experience of both the History curriculum and participation in acts of commemoration.

As you will see as you read through the Content Descriptors, the curriculum opens with a focus on personal commemorations and local history, but quickly turns to national narratives, with no mention of local histories beyond Year 3. The focus is on British settlement, Federation, war experiences and increasing cultural diversity post 1945. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives are often included, although there is only one unit in Year 7 that is dedicated exclusively to First Nations history prior to British colonisation. This chronological exploration of Australia’s history offers teachers opportunities to explore particular moments in greater depth and focus on the development of historical skills as students engage with increasingly complex historical concepts.

Community commemorations

In addition to the learning experiences in schools, our nation also pauses to observe significant dates. The federal public holidays are New Year’s Day, Australia Day, Good Friday, Easter Monday, Anzac Day, Christmas Day and Boxing Day, and each state and territory also observes the Queen’s Birthday and Labour Day public holidays on differing dates. It is clear that these dates are linked to an Anglocentric heritage: Australia follows the Gregorian calendar, marking January 1 as the New Year, observing the Christian holidays of Easter and Christmas, honouring British colonisation on Australia Day and Australia’s links with Britain through the Queen’s Birthday and service in wars, most notably those in support of Britain, particularly on ANZAC Day. Even Labour Day was initially a celebration of the eight-hour work day – part of the working white man’s paradise promised by the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act, more commonly known as the White Australia policy. The next section will focus on two commemorations with the strongest links to the Australian History curriculum: ANZAC Day and Australia Day.

Resources

Watt, D. (2017). Anzac Day traditions and rituals: A quick guide. Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1617/Quick_Guides/TraditionsRituals

ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee, Queensland. (n.d.). Service outline. ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee, Queensland. https://anzacday.org.au/service-outline

Local histories

Bringing history to life in the classroom can prove a real challenge for teachers at all levels. The Australian Curriculum does not undertake any dedicated local history studies, but opportunities exist throughout the curriculum to embed local perspectives.

Relationships with the wider community are key to success here: local museums, historical societies, ‘Friends of…’ organisations, Returned and Services League of Australia (RSLs), and First Nations organisations are all valuable connections to have. It can also be helpful to contact the nearest university, as there may be staff undertaking research on local histories who can assist with resource recommendations or can be asked to give a guest lecture to students.

Ensuring a diversity of perspectives also helps enrich the narrative students build for themselves and their community: every town has people from diverse backgrounds and experiences and students should have the chance to hear from a range of these voices, not a singular narrative. It is also possible to draw on experts who are further afield through videoconferencing and virtual tours. Another important local resource are the memorials and place names in your local area: it is likely that your area has a Memorial Pool, Tobruk Drive, [Name] Memorial Library, and a collection of war memorials in local parks that can be visited and researched to better understand the events or actions of individuals that contributed to these public acts of memorialisation.

Some examples of opportunities to embed local connections include:

- asking RSL representatives to speak during the units on the World Wars, visiting local war memorials and researching the contributions of local service personnel, including women and Indigenous peoples

- Exploring sites, museums, ‘pioneer villages’, etc. that reflect the history of European settlement when teaching about Captain Cook, Federation or the Rights and Freedoms units, including visits with an Elder to local sites of significance for your local First Nations group, and speakers from various community groups e.g. the local Greek Club to speak about their experience as migrants, etc.

- Asking your school administration to add diverse voices to commemorations like ANZAC Day to assist students in better understanding the many experiences had during times of conflict, not only by the soldiers themselves but their families and other groups within the community.

Parliament and Civics Education Rebate (PACER) – ‘The Canberra trip’

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Bob Hawke, the Federal government established the Parliamentary Education Office (PEO) in 1988 and with it the Citizenship Visits Program, which provided financial assistance to schools to bring students to Canberra to learn about Australia’s democratic institutions and visit sites including the Australian War Memorial. The program is now known as PACER (Parliament and Civics Education Rebate) and requires schools to attend:

- an educational tour of Parliament House, and where possible, a role play in the Parliamentary Education Office

- the Museum of Australian Democracy and/or the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House

- the Australian War Memorial

(PACER, n.d.)

This pilgrimage to the nation’s capital is one key way in which students construct their understanding of our national narratives. Australia’s federation, its successes as a parliamentary democracy and sacrifices in defence of that democracy emerge as the key pillars of this narrative. The eponymous ‘Canberra trip’ gives students the opportunity to explore the many ways in which communities commemorate events of national significance. One of the most interesting of these is an exploration of the various monuments which line Anzac Parade, considering their design and the language used in each memorial.

It is clear that both the structure of the Australian Curriculum and civics and citizenship activities and commemorations promoted and observed at a federal level of government promote a national narrative, while at the same time attempting to acknowledge and navigate the fact that this narrative can be problematic, particularly for First Nations peoples. Both the teaching of a nation’s past and the memorialisation and commemoration of events of both national and local significance play a key part for students in understanding the ways in which their society functions, the sacrifices made in the defence of that society and the diversity and richness – with the varied perspectives that come with this – present in both their national and local communities.

Wider reading

Brett, P. (2014). ‘The sacred spark of wonder’: Local museums, Australian curriculum history, and pre-service primary teacher education: A Tasmanian case study. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(6), 17-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n6.8

Clark, A. (2016). Private lives, public history: Navigating historical consciousness in Australia. History compass, 14(1), pp. 1-8

Salter, P. (2015). Local history: Going, going… gone? History Teacher 53(1).

Inglis, K. (2008). Sacred places: War memorials in the Australian landscape. Melbourne University Press.

Kerby, M., Bywaters, M., & Baguley, M. (2019). Australian war memorials: A nation reimagined. In M. Kerby, M. Baguley & J. McDonald (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of artistic and cultural responses to war since 1914 (pp. 553-573). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96986-2_30

Scates, B. (2017). Monumental errors: How Australia can fix its racist colonial statues. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/monumental-errors-how-australia-can-fix-its-racist-colonial-statues-82980

References

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2021). History Rationale. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/humanities-and-social-sciences/history/rationale/

Australian War Memorial. (2021). 25 April Anzac Day. https://www.awm.gov.au/commemoration/anzac-day

Bedford, A., & Wall, V. (2020). Teaching as truth-telling: A demythologising pedagogy for the Australian frontier wars. Agora, 55(1), pp. 47-55.

Billings, B. (2015). Is Anzac Day an incidence of ‘displaced Christianity? Pacifica: Australasian Theological Studies, 28(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1030570X16682526

Fortin, J. (2017, August 17). Topping monuments, a visual history. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/17/world/controversial-statues-monuments-destroyed.html

Holbrook, C. (2014). The role of nationalism in Australian war literature of the 1930s. First World War Studies, 5(2), 213-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475020.2014.913988

Holbrook, C. (2016). Are we brainwashing our children? The place of Anzac in Australian history. Agora, 51(4), 16–22.

Inglis, K. (1965). The Anzac tradition. Meanjin Quarterly, 24(1), 25–44. https://meanjin.com.au/blog/the-anzac-tradition/

Inglis, K. (2008). Sacred places: War memorials in the Australian landscape. Melbourne University Press.

Lake, M. (2010). Introduction: What have you done for your country?. In M. Lake & H. Reynolds (Eds.), What’s wrong with ANZAC?: The militarisation of Australian history (pp. 1–23). University of New South Wales Press.

Mali, J. (2003). Mythistory: The making of a modern historiography. Chicago University Press.

McKenna, M. (2007, 6 June). Patriot act. Australian Literary Review, 2(5), 14-15, 16.

McKenna, M. & Ward, S. (2007). ‘It was really moving, mate’: The Gallipoli Pilgrimage and Sentimental Nationalism in Australia. Australian Historical Studies, 38(129), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/10314610708601236

Modhin, A., & Storer, R. (2021, Jan 30). The reckoning: The toppling of monuments to slavery in the UK. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/jan/29/the-reckoning-the-toppling-of-monuments-to-slavery-in-the-uk

PACER. (n.d.). PACER institutions. PACER. https://www.pacer.org.au/attractions/mandatory-attractions-to-visit/

Rhoden, C. (2012). Ruins or foundations: Great War Literature in the Australian curriculum. Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, 12(1). http://openjournals.library.usyd.edu.au/index.php/JASAL/article/view/9811

Scates, B. (2006). Return to Gallipoli: Walking the battlefields of the Great War. Cambridge University Press.

Scates, B. (2017). Monumental errors: How Australia can fix its racist colonial statues. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/monumental-errors-how-australia-can-fix-its-racist-colonial-statues-82980

Sorabjee, M. (2016). The power of simplicity: 8 moving minimalist memorials. Architizer. https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/minimalist-memorial/

Stanner, W. (2000). After the Dreaming. In D. McDonald (Ed.), Highlights of the Boyer Lectures 1959-2000. ABC Books.

Twomey, C. (2015). Anzac Day: Are we in danger of compassion fatigue? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/anzac-day-are-we-in-danger-of-compassion-fatigue-24735