5 Fostering first year nurses’ inclusive practice: A key building block for patient centred care

Professor Jill Lawrence and Natasha Reedy

What can we do as university teachers to enable first year nurses to embrace and honour diversity and to begin to develop their inclusive professional practices?

Key Learnings

- Communication and critical theories can draw our attention to the complexity of communication in Australian health care contexts

- Health care contexts are becoming increasingly diverse with differences in cultural, group and gender identities now being voiced

- A professional nursing identity involving the overarching concept of patient centred care encompasses inclusivity: the acceptance and capacity to cater for the needs of each individual patient

- Nursing students need to reflect on their self-awareness, as well as develop their professional identity, so that they can more effectively demonstrate patient centred care

COMMUNICATION AND CRITICAL THEORIES

Communication and critical perspectives can focus attention on the complexities of communication in a diverse, changing and complex context like health care. Understanding how communication perspectives have evolved helps us appreciate the implications of this diversity and complexity and may provide approaches to developing more inclusive practice.

Models conceptualising communication theory have evolved from Shannon and Weaver’s (1948) rudimentary linear model. This model reflected the idea that there was a message as well as a sender and receiver who had little to do with the interpretation of the message so that the message was seen to be essentially independent from both the sender and receiver. While this model does not reflect the two-way nature of communication, nor the role that the sender and receiver both plays, we often communicate as if this were the case. Have you been in a classroom where the teacher transmits their lesson without acknowledgment of either verbal or nonverbal feedback and assumes that students receive the message in the way it was communicated with 100% accuracy? While the linear model did concede that sometimes the message was not effective, it only recognised one form of communication barrier, that related to physical noise [such as a computer falling].

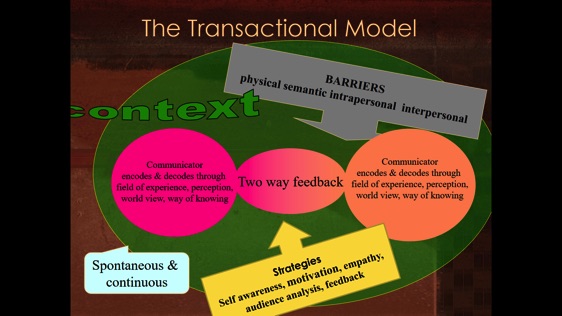

A more sophisticated model of communication, the ‘interactive’ model of communication, updated the linear model by incorporating the sender’s and receiver’s perceptions into the model. Within this model, a communicator’s perceptions or fields of experience are identified as playing a decisive role in the effectiveness of communication. In addition, the concept of two-way feedback was also identified as being integral to effective communication processes.

Without two-way feedback , communication could be interrupted or disrupted by barriers that can impede the process of communication. For example, semantic or language and word barriers can occur along with psychological or intrapersonal barriers. Intrapersonal barriers stem largely from our perceptions of ‘difference’ or diversity. They include the assumptions that we make about others and the differences between us. They also encompass our expectations, our fears and anxieties and prompt us to stereotype people which in turn can lead to bias, prejudice and labelling. Likewise, our cultural understandings / misunderstandings can also lead us to experience interpersonal barriers which can emerge largely from cultural or gender difference[s].

A third, more advanced ‘transactional’ model of communication also appreciates the simultaneous and continuous nature of communication, as well as the fact that communication occurs within a context (a time, place, situation or relationship). The transactional model also identifies communication strategies that can be employed to alleviate barriers: self-awareness, motivation, audience analysis, listening, empathy (Engleberg & Winn, 2015), assertiveness and feedback. Figure 5.2 demonstrates these ideas.

This chapter will explore how these communication barriers, and the strategies to overcome them, underpin the themes of diversity and inclusion in the specific context of healthcare and as enacted by students learning to construct or develop their identities as professional nurses.

Critical theory adds to communication perspectives by considering the ways in which perception shapes communication as a way of maintaining existing regimes of privilege and social control. Its role is so critical that it is defined as a threshold concept in a number of disciplines. In anthropology or ethnography it is defined as culture, and in critical theory as world view, way of knowing or discourses.

In this chapter we define perception as culture and appreciate that all human beings, including ourselves, have and make culture and that culture is reflected in our everyday activities, relationships, social processes, our values, beliefs, norms, customs, possessions, rules, codes, and assumptions about life. Shor (1993) (as cited in Lankshear et al., 1997) argues that “culture is what ordinary people do every day, how they behave, speak, relate and make things. Everyone has and makes culture … culture is the speech and behaviour of everyday life”(p. 30).

Our often taken-for-granted cultural understandings instil ideologies and power structures with the purpose of reproducing conditions in ways which benefit the already-powerful (Giroux, 2007). Advocates of critical pedagogy view communication as inherently political and reject the neutrality of knowledge (Giroux, 2007). In this way, differences from the norm, or the understood, accepted or taken for granted ways of knowing or mainstream culture, are seen to be deficit. Many of us live in a homogenous or common culture that we take for granted and accept as ‘natural’ or ‘normal’. Some of us do not question this cultural understanding. We might not have been exposed to individuals with different perspectives, perceptions of backgrounds, to different groups or cultures or to different ways of understanding and knowing.

Previous chapters have explored how we communicate using specific verbal practices and nonverbal behaviours. This helps us to understand that the same act can have different meanings in different cultures. This includes differences in the cultural understandings of individually and collectively orientated cultures, and the cultural differences in the way females and males and gender neutral or transgender individuals communicate.

If these understandings from communication and critical theories are merged, then elements of the communication process, for example the context of the communication, the role of culture and the barriers to communication, can be acknowledged as the means by which those in power, whether individuals, organisations or communities, can make judgements that can disempower or marginalise those who are assumed, labelled or stereotyped as being ‘different’. Alternatively, if other elements are prioritised or reimagined, then these communication elements can become agencies of empowerment and transformation. For example, empowering elements can encompass self-awareness and an understanding that our own perceptions, culture, world view or way of knowing is just one of many, and that other world views are as equally legitimate as our own.

The chapter will explore these understandings by applying them to the diversity present in the health care context – differences displayed by both patients and staff in the context – as well as to the ways in which student nurses can learn to be more inclusive of the differences they encounter in a health care context.

DIVERSITY IN NURSING

Diversity is ever-present in the health care context. Australia is a multicultural country. In addition, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been in Australia continuously for 60,000 years (Hazelwood & Shakespeare-Finch, 2010). Everyone else is an immigrant of less than 250 years. Australia also has a high level of first-and second-generation immigrants. In 2016 the Australian National Census demonstrated that 33.3 % of Australians were born overseas, and a further 34.4% of people had both parents born overseas. However, numbers of migrants and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people vary across Australia. For example, only 1.6 per cent of the South Australian population identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people compared to 27.8 per cent of people in the Northern Territory (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2006).

Despite this diversity in the population, Western ideas of communication are the taken-for-granted way of communication in Australia. For example, English is used as the standard language, written communication is valued (in legal matters) and the accessibility of ideas (through the internet), is a taken-for-granted notion reflecting the individualised Western way of communicating.

With increases in the numbers of graduating nurses born outside Australia, being part of a multicultural healthcare team is now standard in most workplaces. In 2011, 33 per cent of nurses, 56 per cent of General Practioners [GPs] and 47 per cent of specialists in Australian were born overseas (ABS, 2013). This is significant, as the continuing increase of medical professionals from other countries enriches the workplace. However, it can also present many communication challenges in the healthcare environment. The increase in English language proficiency requirements for a registered nurse in Australia (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency [AHPRA], 2014) has reduced spoken-language errors in healthcare environments. However, given that less than 7–10 per cent of the meaning of communication is from verbal communication (or the words alone), there is still a high potential for miscommunication when there are cultural differences in team membership in healthcare settings.

Nurses work in these diverse contexts, with diverse groups and individuals and care for diverse patients or clients. Like educational institutions, health care is at the forefront of diversity. As Crawford, Candlin and Roger (2017) contend, with increasing cultural diversity among nurses and their clients in Australia, there are growing concerns relating to the potential for miscommunication, as differences in language and culture can cause misunderstandings which can have serious impacts on health outcomes and patient safety (Hamilton & Woodward-Kron, 2010). Grant and Luxford (2011) add that there is little research into the way health professionals approach working with difference or how these impact on their everyday practice. Furthermore, there has been minimal examination of intercultural nurse–patient communication from a linguistic perspective.

Applying communication and critical models and strategies to nursing practice can help nurses understand what is happening in their communication with patients, particularly where people from different groups or cultures are interacting. Applying these approaches can help to raise awareness of underlying causes and potentially lead to more effective communication skills and therapeutic relationships, and therefore enhanced patient satisfaction and safety.

APPLYING COMMUNICATION PERSPECTIVES TO DIVERSITY IN THE HEALTHCARE CONTEXT

Semantic, language and words are barriers that emerge in health care contexts (Graham & Lawrence, 2015). When first entering any unfamiliar healthcare context or workplace, it is important to recognise there will be a new or unfamiliar language. Out of necessity, healthcare environments use healthcare jargon terms, which confuse not only new healthcare professionals but patients as well. This language use can lead to semantic barriers and generate difficulties in interactions with healthcare professionals (Graham & Lawrence, 2015). To complicate matters, there are many commonly used healthcare acronyms related to medication and treatment that are specific to specialised areas. Many are Latin, and their full meanings not intuitive – particularly for students whose first language is not Latin-based like English. Examples include mane (morning), nocté (night), prn (when required), stat (immediately), tds (three time a day) – there are many others.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC, 2011) has published a list of acceptable commonly used abbreviations /acronyms and identified abbreviations that have caused adverse patient events due to the acronym being mistaken for something different. For example, the abbreviation/acronym CA can be written to represent carbohydrate, (cancer) antigen, cancer, cardiac arrest or community-acquired. ACSQHC recommends writing the full medical term in patient charts, followed by its acronym, in the first instance to ensure patient safety. Despite these recommendations, it is common in healthcare settings to hear sentences constructed almost entirely of healthcare jargon and acronyms.

Intrapersonal and interpersonal communication barriers can be endemic in the health care context. From a cultural perspective, the power distance or hierarchical structure within healthcare settings are much more structured and more clearly defined than in the wider Australian communities. Similarly, the need for clear lines of authority and the call to minimise ambiguity in all communication to safeguard patient safety, mean communication within healthcare settings tends to be much more direct than it is in the broader population. Outside health care, such power differences are less clearly defined, and might even be able to be avoided completely. In a case such as this, where patient needs are paramount, healthcare staff need to develop strategies for communicating and effectively advocating for their patients.

Patients and healthcare staff who have grown up in a collectivist culture are likely to have a stronger sense of family commitment than is typical in the broader Australian community. Although Australian healthcare staff, patients and family members care deeply about family members, they are more likely to negotiate caring responsibilities with others. Being from a collective culture may mean healthcare staff are unavailable to work due to family commitments, or patients’ relatives may insist on staying with an ill family member in hospital during treatment. This strong sense of family duty, and the resulting obligations are amplified when accompanied by strong loyalty. It is important that this deep sense of duty is recognised and accommodated where possible.

The non-verbal element of personal space is another area of significant difference between broader Australian culture and healthcare culture. For example, when providing treatment, nurses need to be physically closer to patients than is usual outside a healthcare setting. Although healthcare professionals are accustomed to close physical and often intimate personal interactions, they still need to gain consent from patients and explain what is being undertaken and why it is important. The need for this consideration is even greater in cultural groups where higher levels of personal modesty are the cultural norm.

With such diversity and difference present in health care contexts, how do nursing students begin to develop an approach that assists them to understand the depth of diversity and its impact on their professional nursing practice? How do they develop an approach that is inclusive of the diversity they encounter in the health care context? In nursing an inclusive approach is synonymous with the concept of Patient Centred Care. The next section explains how student nurses can be encouraged to think about who they are and why they need to focus on developing their patient centred care, or an inclusive approach to their nursing practice.

PATIENT CENTRED CARE

Patient (person) Centred Care [PCC] is a care approach that considers the whole person and is important for nurses to be aware of in order to inform and foster inclusive care practice and ‘become ‘ a Registered Nurse. A PCC approach improves health outcomes of individuals and their families (Arbuthnott & Sharpe, 2009; Arnetz et al., 2010; Beach, et al., 2005; Boulding, Glickman, Manary, Schulman, & Staelin, 2011). It is a concept that consists of several constructs and as a consequence, a globally accepted definition of PCC is yet to be formed. The main widely accepted constructs of PCC include person, ‘personhood’ and effective communication.

The term ‘person’ acknowledges a human being has rights, especially in relation to decisions and choice (including being sensitive to nonmedical/spiritual aspects of care, patient needs and preferences), and being respected (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2012; International Council of Nurses, 2012; United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 1948; 1976). The term ‘person’ reflects that a person is a human being, who is made of several human dimensions. These dimensions include intellectual, environment, spiritual, socio-cultural, emotional, and physical, all of which operate together to form the whole person (Smith, 2014).

Personhood is the expression of being human, that is one’s humanity. A nurse can seek out an individual’s personhood by spending time communicating with them (the patient). In particular, communicating with them in order to find out what interests them, what is important to them, what concerns them and what threatens them (Dempsey, 2014). Importantly though, the element of PCC vital to improving health outcomes is presence of effective communication between the nurse and the patient and the patient’s family in order to facilitate information sharing (Dempsey, 2014; Kitson, Marshall, Bassett, & Zeitz, 2012).

For communication to be effective, it needs to be based on mutual trust and respect. Trust and respect are key enablers in the establishment of a therapeutic relationship with patients (Dempsey, 2014; Kitson, et al., 2012). Other core dimensions of PCC include: education, emotional and physical support, continuity, transition and coordination of care, involvement of family and friends and access to care (ACSQHC, 2011). When delivering PCC, it is important to consider all these constructs and dimensions as a whole unit, and how they work in unison to improve the health and wellbeing outcomes of a patient and their family. Therefore, as first year nurses, awareness of these PCC constructs and their benefits are essential in order to foster inclusive care practice.

The next step is to provide student nurses with several building block activities, designed to:

- Raise their self-awareness of the values they hold as ‘being’ human’ and their associated behaviours in a everyday way of being.

- Raise their awareness of the values the nursing profession holds.

- Identify ‘ways of being in every day practice’ in order to develop the values and behaviours that the nursing profession holds in promoting inclusive care practice.

Reflection

The following activity can help us to understand the implications of this way of thinking in our approach to the values we hold.

What do we value in ‘being’ human?

- Reflect on the values you place on being human. Write down your thoughts in the first column.

- What behaviours shows these values in action? Write down these behaviours in the second column.

| Values I place on being human | Behaviours that reflect my values in being human |

|

|

The nursing profession holds specfic values in relation to ‘being’ human. There are, for example, multiple Codes of Practice that designate these values. These include the International Council of Nurses (2012) with the ICN Code of Ethics for Nurses, the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia’s (2018) Registered Nurse Standards for Practice and the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, and the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia’s (2018) Code of Professional Conduct for Nurses in Australia. Today’s rapid changes in value systems in society are causing health care to encounter more ethical and philosophical challenges at providing care to its clients. These changes have created diverse and changing nursing environments that require professional nursing.

- What behaviours would you show to reflect these values in your inclusive professional practice?

- Write down these behaviours in the second column.

| Values we placed on being human | Behaviours that reflect our profession’s values in being human |

|

|

Now we compare our personal values to the professional values towards ‘being’ human to help us develop inclusive practice?

- Circle the values and corresponding behaviours that are a match.

- Identify the values and the corresponding behaviours that do not match by highlighting these with a highlighter pen.

- Write down three strategies you could begin to implement in your everyday ‘way of being’ (behaviour) towards other people, to address areas that were a mismatch to your professional codes of practice.

| Strategies to implement to improve my way of being with others to ensure my behaviour reflects the nursing standards and codes of practice | |

| 1.

|

|

| 2.

|

|

| 3.

|

|

We can see how developing the concept of professional behaviours, or in the context of health care, Patient (person)-centred care, is a professional approach that considers the whole person and is important for first year nurses to be aware of in order to inform and foster their inclusive care practice in ‘becoming’ a Registered Nurse. By considering the patient as a person with their own values, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, student nurses are beginning to overcome some of the barriers that can arise when they communicate across difference. The following case study shows how one student is developing her person-centred care.

Case Study

I would like to show I care as a student nurse on my first clinical placement firstly by getting to know the people I will be working with, by understanding my scope of practice through a thorough orientation, not being too nervous and hopefully feeling relaxed and confident, this will certainly put me in better stead to show my caring nature. I will ask many questions (at appropriate times) to help me to understand conditions and diagnosis and this will assist me to understand about the people in my care. Building a rapport with patients and taking the time to get to know them will be top of the list for showing I care for patients, I would also build rapport with their families to help ease their worry, as I know it is awfully difficult leaving a loved one in hospital and uncertainty of the unknown and wishing there was more they could do. Through a transactional communication model, congruent body language, displaying genuine interest, being empathetic, positive, encouraging, honest and respectful and culturally aware, I will hopefully be off to a good start in showing my caring nature on my first student placement.

In this next section we link ideas derived from communication and critical perspectives and those of Patient Centred Care to the strategies or skills and competencies to enhance an inclusive approach in a health care context.

A CONCEPTUAL MODEL TO DEVELOP AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH

A conceptual model to develop an inclusive approach presents three practices that emerge from integrating communication and critical theories with Patient Centred Care (Lawrence,2015). The three practices include self-awareness and reflective practice, communicative practice and critical awareness of context (or critical practice). The practices underpin a conceptual model depicted below in Figure 5.4.

SELF-AWARENESS AND REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Developing self-awareness is more complex than most people imagine. It is difficult to change or shift our taken-for-granted assumptions and expectations and to accept others’ differences without judging them. Listen to this TED talk about cultural identity, how our lives, our cultures, are composed of many overlapping stories. Novelist Chimamanda Adichie tells the story of how she found her authentic cultural voice — and warns that if we hear only a single story about another person or country, we risk a critical misunderstanding.

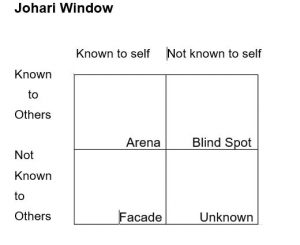

To encourage nursing students to make this shift they are asked to reflect on their self-awareness by using the Johari window. The activity below assists them to accomplish this.

Activity 1

Develop your self-awareness with the Johari Window

- Watch: The Johari Window in Model

- Complete the quadrants of the Johari window reflecting about your nonverbal communication as an example. Then, ask a peer, class or work colleague or friend, family member, etc. to add their reflections about your nonverbal communication.

- Reflect about what you might have discovered about your own self-awareness. How could you learn more about how others perceive you?

- Culturally safe and respectful practice requires having knowledge of how a nurse’s own culture, values, attitudes, assumptions and belief’s influence their interaction with people and families, community and colleagues.

- Refer to the Code of Conduct for nurses (NMBA, 2018). Which principle/s do you think aligns with this activity?

Activity 2

Interview someone who has worked in a health care context and ask them about their experiences and what helped them to be confident in the new context.

- Your task is to ask your interviewee about their nursing experiences / problem solving strategies they have developed; what worked for them; did they become more comfortable in a clinical situation; how did they balance life, study, children and work; something they found unexpected; one thing they wished they had known at the start.

Activity 3

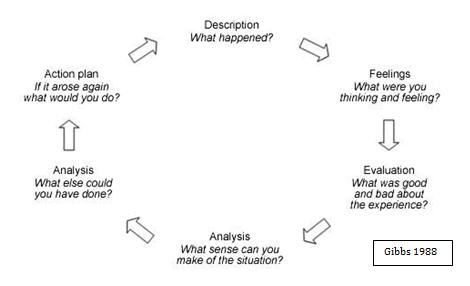

Build your reflection skills by practicing Gibb’s reflective cycle (1988).

- Reflective practice is another important strategy you can engage in to develop your self-awareness, understanding of situations and interactions encountered in practice and your own responses to these. There are quite a few frameworks for reflective practice.

- Apply the stages of Gibbs Reflective Cycle to the interview you conducted in Activity 2. In the feelings stage outline one surprising thing that you discovered about nursing and patient-centred care that differed from the expectations you had about nursing and in the action plan stage put forward a strategy that we can use to become comfortable with an unfamiliar group or individual in a context is our ability to reflect on the behaviours, languages or jargon in the context.

In a practical sense this means that we need to observe, monitor, to watch, listen to and reflect on other’s or the group’s behaviours and practices and to learn from our observations. In a health care or clinical context for example, how do you address clients, colleagues and supervisors? What happens if you don’t do this well? Where do you need to go to find out about the accepted requirements for interaction? Is there a source of help and assistance? Lawrence (2015) suggests that one way to learn how to understand this is to watch how our colleagues and clinical supervisors communicate with us, analyse their practices, the kinds of information that are valued and begin to develop evidence-based practice. What do our studies inform us about? What does the research literature say? What exactly does this mean for our practice and our communication in that context? Good observation techniques can save us a lot of time as well as help to identify the group and/or individuals we need to communicate with in the new context. It is important to recognise too that if we do not know the practices in the new context, we are not deficient, we are unfamiliar.

COMMUNICATIVE PRACTICE

The second practice relates to communication. Communicating effectively helps gain and develop an understanding of an unfamiliar culture, group or person being engaged with as well as their specific behaviours and practices. The specific communication strategies discussed here include seeking help and information, participating in a group or team, and making social contact and conversation. In terms of communication theory, these practices signify ‘feedback’ and facilitate more effective communication between communicators.

Seeking help and information is an important communication strategy which cannot be underestimated. It is critical in understanding another’s’ beliefs, values and cultural practices. We cannot assume that we can understand another person or patient because they are a certain age, nationality or have a certain sexual preference. We have to seek their help in developing our understanding of them, and in a health care context our understanding of their needs and requirements.

In daily life the evidence is overwhelming. Kids Help Lines assist younger people cope with changes in their lives. Cancer Support groups are set up to help people diagnosed with cancer to develop sources of support and information. The following case study documents students’ clinical experiences of seeking help and information.

Case Study

I would admit it has been difficult to understand some of the strong ethnic accents when they talk. I don’t want to appear rude but I have to ask them to repeat what they have said.

One of our Indian CNs wasn’t able to communicate with an old digger who was being quite rude and abusive to her. She asked me if I would assist him as there was not going to be the opportunity for her to do so as he was not going to change his mind. She wasn’t upset or angry, she tried, she handed over and all was good, because I was able to culturally communicate with him, as I am Australian, from the bush with a military background. Nurses need to work with the understanding that no two persons are the same and communication and respect are important.

I found that working for Blue Care and in the hospital the problem with communication is either with the patient or client (most elderly) who is hard to understand as they are unable to speak clearly and unable to voice their concerns. Or that information was not handed over properly, as staff are usually flat out and understaffed. I find it’s better to go to the patient’s care plan or file and look at progress notes thus getting a basic detail of the history of the person. I feel if we just take a little bit of time and to listen to others we might hear something, others can’t hear.

It is important to reflect on our own attitudes to asking for help. Some people don’t find it easy to ask for help. Kossen, Kiernan and Lawrence (2017) suggest that some may believe asking for help is a sign of ‘weakness’ while others may feel that they lack the confidence to ask. Still others might be reluctant to ask because they are overconfident about their own abilities. Others may feel they do not have the ‘right’, or believe that they could be considered ‘stupid’, or they may equate help as ‘remedial’. Other groups’ cultural belief systems may not value asking for help or do not prioritise it.

Case Study

Again students reflect about why they felt unwillingness to ask for help and support.

Sometimes, my fear of conflict prevents me from communicating effectively because I tend to keep quiet rather than express my own point of view or speak up if I feel something is incorrect. Sometimes I cannot understand the supervisor what he means, so I must ask again. This is really uncomfortable for me. The biggest part of communication is to have to ask for help. Recently I asked for help from one of my colleagues and was nervous to see them as I may appear stupid for just not getting it.

Reflection

- Reflect about your approach to asking for help. For example, do you hesitate to ask because it is difficult for you?

- I sometimes hesitate because I sometimes feel that I do not like to bother people with my problems?

Asking for help is critical in building our learning capacities, so it is vital not to minimise the value of this skill. However it must be done appropriately and professionally. We need to prepare ourselves, for example asking ‘who to ask’ and ‘how to ask’. The question about ‘who to ask’ often requires research. The most appropriate one to use may need prior investigation, where we use sources of information gained by making social contact and conversation. It is also useful to reflect on how to seek help and information. This is because the way that we ask needs to be socially and culturally fine-tuned to the particular context. In relation to verbal communication, we may need to consider the actual words we will use. Will we use colloquial language or jargon, long sentences or short sentences? Will we prepare and practice how to ask? Will we ask directly or indirectly? How close will we stand?

Physically, how and where we will ask for help (in consultation times, on a forum, using email, through an appeal if it is about a grade)? In terms of nonverbal communication we would need to think about our gestures, facial expression, body language and whether we use direct or indirect eye contact. In terms of paralinguistics what tone of voice, what pace, volume and pitch will we use? We need to ensure our choices are appropriate to our context. The verbal and non-verbal ways we would seek help and information from a lecturer would, for example, differ from the ways we would ask our friends or our employer or a client in an aged care institution.

Participating in a group or team

The communication strategy used when participating in a group or team can help us develop our confidence as well as contribute to critical thinking and questioning. This is essential in both learning and professional contexts and is crucial in team-centred workplaces like nursing or healthcare contexts.

Case Study

Students reflect about their use of this strategy or practice using online tools:

Having things like blackboard collaborate was extremely beneficial. The feedback, the advice I received, and the fact that I saw that people were in a similar boat with study helped me stay focused and determined.

I had what I thought was a lot of experience when it came to acquiring information from digital resources. When it comes to developing my skills I realised I am not as knowledgeable as I thought. There are more ways to access information that I had no knowledge of or had access to. I found that participating in online forums was very helpful in learning due to giving and receiving advice from and to other students. I am gaining a lot of confidence and more digital literacy skills.

Reflection

- Observe your colleagues’ and peers’ use of team work.

- Write down one example of a strategy that contributes to effective teamwork and one strategy that negatively affects the team’s productivity.

Building team and group capacities not only helps gain confidence in performing in health care contexts, they can also help gain employment and/or promotion. Team and group capacities assist with accomplishing professional tasks more effectively and productively. However, the verbal and nonverbal behaviours and cultural beliefs underlying this skill also change from person to person, culture to culture, place to place, context to context. Some individuals may feel more comfortable with team work while others prefer to work independently. Some groups enjoy early getting-to-know-you humour before they progress to the actual work of the meeting, hand over or consultation? Some groups are more collectively orientated while others more individually orientated. Cross-cultural theory sees these differences in behaviours as cultural practices or cultural literacy. But the fact is that we often take our own behaviours and practices for granted while perceiving others’ ways as different or deficit. It is important to stress that one way is not better than the other – just different.

Making social contact and conversation

This practice not only increases our sources of support it also assists in brainstorming solutions or solving problems. Confidence in employing this practice will increase our capacity to develop networks, learning circles, mentors, friends and partners.

Case Study

Again students reflect on their capacities to make social contact.

When I came here in Australia five years ago, my communication skills were very limited. High school helped me a lot and talking to different people in English really built up my communication skills. I have a great support system around me including two great girls who I have met on clinical. It is great to have them to talk to and ask questions we also keep each other on track. I also have a friend who graduated last year so this is also a great avenue to receive information and get help. I will be working in the industry during my studies so I believe I will have plenty of help from experienced nurses when I need it.

I didn’t know anyone when I started, but I met a 2nd year undergraduate in the library who took me under her wing and showed me how to use the library, photocopier, Study Desk online and forums. She also added me to her study group on Facebook. I was very thankful that she took her time to show me these vital things.

Reflection

- Observe your colleagues and peers’ use of this strategy.

- Write down three approaches that you would feel comfortable in using to make social contact.

Again there can be differences in the ways that individuals and groups approach this strategy as its use needs to be socially and culturally fine-tuned to the specific context or situation. Its use depends on a very complex social and cultural interplay of factors. For example, do you need to be introduced before you are able to meet someone? Do you need to think of a suitable topic with which to start a conversation (for example the weather, a significant cultural event)? Are there ‘taboo’ subjects which could lead to a communication barrier or even offense? What kinds of personal information can you use to help authenticate your status and position which may be necessary for establishing relationships in particular cultural groups? Are there any unwritten social mores regarding this skill which would mean that if you were to ignore or overlook them would there be a risk offending someone?

Critical awareness of context

The third practice is the most difficult. Critical practice moves beyond our self-awareness of our own belief systems and cultural practices to include an awareness of the relationships in operation around us. This is called critical self-awareness or more generally critical practice. Critical practice involves a) the ability to seek and give feedback about specific practices and belief systems and b) an awareness of the power relationships operating in the context or culture.

Seeking and giving feedback is critical. For example, teachers give feedback all the time in assignments, in class and on forums. Students want feedback as feedback assists students to improve their skills and knowledge. In a nursing workplace there will be performance reviews and case conferences and seeking feedback allows you to learn more about your own practices and beliefs as well as those of your colleagues and peers. It also allows you to check whether your understandings and interpretations about these are accurate. Asking for and giving feedback is also an empowering strategy. When it is positive it can facilitate teamwork, improve interpersonal relationships and lead to greater productivity.

Providing constructive feedback or negative feedback, in socially and culturally appropriate ways, can be a difficult and risky strategy. It can be vital in being assertive, in putting forward your point of view, in developing flexibility, in time management, in preventing stress and in minimising conflict. For example, in keeping patients safe, sometimes nurses have to take their colleagues to one side and tell them that they are not doing something correctly or the way they communicate with others is not being well received. If you are inadvertently offending someone then it is much better if that person were to let you know.

Case Study

Student nurses reflect about situations where feedback became an important strategy in avoiding communication barriers and in enabling them to fulfil their study goals.

The communication error I witnessed was in my class. We were learning about long bones, and our practical involved dissecting a bone from a cow. Our lecturer completely forgot to mention that the bone was from a cow. We cut the bone, and one lady was standing back. It was lucky that she realised herself that it was a cow’s bone, as she followed a religion which meant that the cow was a sacred animal to her religion. It was an honest communication error in which the lecturer apologised profusely.

If someone is offending you then it is important for you, in a socially and culturally acceptable manner, to provide them with some constructive and careful feedback that would help to overcome this potential barrier between you and the other person. You could, for example, use the the following strategy:

- Prepare what you want to say, as well as when, where and how, beforehand.

- Start with something positive and/ or place yourself in their situation (be empathetic).

- Give your reasons and/or explanations for why you feel offended/disagree.

- Provide an alternative or state what specific action you would like them to do.

Reflection

Provide some examples of where you either sought or gave feedback about specific practices whether or not they achieved the solution you were aiming for.

- For example, you might want to give a lecturer feedback about how marks were distributed in an assignment.

- Your outcome might be to have your marks increased.

Power relationships

Power relationships operating in the culture or context can affect our effectiveness. If you were studying social science or politics you would be studying power relationships for the entire degree. Power is the ability to influence or control the behaviour of people. Sometimes power is seen as authority which is the power which is perceived as legitimate by the social structure surrounding the context. Examples would encompass a Federal or State or Local Government, a Hospital Board, the University Council. Sometimes power can be seen as evil or unjust and you might agree or disagree with the decisions made.

However the exercise of power is accepted as pervasive to humans as social beings. In the business environment, power can be upward or downward. With downward power, a company’s superior influences subordinates. When an organisation exerts upward power, it is the subordinates who influence the decisions of the leader. In higher education academic staff can be seen as having more power than you as first year students? Health care workers or nurses will be witnesses to power relationships both in their studies and clinical experiences. Domestic violence, whether physical or verbal, is an expression of power.

Case Study

In thinking about my conversations about caring I engaged with the concept of putting on a new face for the next patient you see, I find this particularly difficult as I can be emotive at times and this is something that I will be working on for my future practice. I am also aware that body language has an important role in this interaction and my facial expressions can give me away at times also. Other strategies that I use to communication towards others is talking at the eye level of the person instead of standing over them, sitting beside their bed so there is no power play happening as I believe we already display a power imbalance through our knowledge, practice and skills we have developed so the patient who is unwell and in a vulnerable position, whether they are laying down, sitting, or with people standing over them can be at eye level. Ways in which I have shown care is by building a rapport with people and their families, asking about their interests, their concerns by actively listening, acknowledging, paraphrasing to understand and responding appropriately also giving space or silence when needed. I also like to follow up any with any questions that the person has that I may not have the answer to and respond back in a timely manner or refer the person to someone who may be able to explain, I like to be authentic and honest. In times that I have shown care towards others it has mostly been positive although there were times when the person was in pain or just fed up with their situation and they were short with me or just plain rude and abrupt and this was understandable considering their situation, so not taking everything on board is important when caring for people and usually an apology slips in down the track when they are feeling better, although I have explained sometimes to people I care for that “I am doing my very best and I understand you are not well, but let’s try and get through this together” that usually puts a different spin on the outcome of care and a genuine, honest understanding of each other.

I am of Aboriginal decent but due to my appearance am not recognised as such by the public. An example of discrimination was in a meeting group when one lady very openly pronounced some offensive things not only in front of me but also in front of another fellow Aboriginal student. We were all offended by the comments but chose to only discuss our feelings amongst ourselves afterwards. This was very unprofessional and in a patient/professional environment very inappropriate.

Reflection

• Reflect about when you may have experienced or witnessed discrimination

The three practices are lifelong learning skills that can assist us to be more inclusive and help nurses practice patient centred care. For example each will have particular ways of communicating and operating. The practices can instil in us a resilience that enables us to apply and re-apply these practices so that we are empowered to practice inclusivity whenever diversity emerges in the fast moving and complex world in which we live.

Conclusion

This chapter explored how our awareness of self shapes our capacities to adapt to develop a more inclusive approach to diversity by integrating the concept of Patient Cantered Care. Patient Centred Care was described as an inclusive practice that new student nurses need to understand and practice as they progress through their degrees. The twin concepts of awareness of self and awareness of context were used to inform a model of inclusion. The model emphasises the use of self-awareness and reflective practice, communicative practice and critical awareness of context. These practices can assist nurses to develop patient centred care, at its heart an approach that by its nature, is inclusive.

References

Adichie, C. N. (2009). The danger of a single story [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006). Census findings 2006. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/historicaldata2006?opendocument&navpos=2

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015). Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4430.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Census findings 2016. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Home

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC]. (2011). Patient-centred care: Improving quality and safety through partnerships with patients and consumer. Sydney, Australia: ACSQHC.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC]. (2012). Patient-centred care: Improving quality and safety through partnerships with patients and consumer. Sydney, Australia: ACSQHC.

Australian Council of Social Service. (ACOSS). (2012). Poverty in Australia, 3rd edition. Retrieved from http://acoss.org.au/images/uploads/Poverty_Report_2013_FINAL.pdf.

Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency [AHPRA]. (2014). Australian Health Practitioner

Regulations. Retrieved from https://www.ahpra.gov.au/

Arbuthnott, A., & Sharpe, D. (2009). The effect of physician-patient collaboration on patient adherence in non-psychiatric medicine. Patient Education and Counselling, 77, 60-67.

Arnetz, J. E., Winblad, U., Lindahl, B., Höglund, A. T., Spångberg, K., Wallentin, L., Wang, Y., Ager, J. & Arnetz, B.B. (2010). Is patient involvement during hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction associated with post-discharge treatment outcome? An exploratory study. Health expectations. 13(3), 298-311.

Beach, C. M., Sugarman, J., Johnson, R. L., Arbaleaz, J. J., Duggan, P. S., & Cooper, L. A. (2005). Do patients treated with dignity report higher satisfaction, adherence and receipt of preventative care? Annals of Family Medicine, 3(4), 331-338.

Blake, B. (Author). (2014). The Johari window model [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWii4Tx3GJk

Bottrell, D., & Goodwin, S. (2011). Schools, communities and social inclusion. South Yarra, Australia: Palgrave Macmillan.

Boulding, W., Glickman, S., Manary, M., Schulman, K., & Staelin, R. (2011). Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. American Journal of Managed Care, 17(1), 41-48.

Cancer Council Queensland. (2019). Cancer support groups. Retrieved from https://cancerqld.org.au/get-support/cancer-emotional-support/support-groups/

Corocran, T., & Renwick, K. (2014). Critical health literacies? Introduction. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 5(3), 197-199. doi:10.1080/18377122.2014.940807.

Crawford, T., Candlin, S., & Roger, P. (2017). New perspectives on understanding cultural diversity in nurse–patient communication. Collegian, 24(1), 63–69. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2015.09.001.

Dempsey, J. (2014). Introduction to nursing, midwifery and person centred care. In J. Dempsey, S. Hillege, & R. Hill (Eds.), Fundamentals of nursing and midwifery: A person centred approach to care (pp. 4-16). Sydney, Australia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Engleberg, I.N. & Wynn, D.R. (2015). Think Communication, Boston, MA:Pearson Education.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford, England: Oxford Further Education Unit.

Giroux, H. (2007). Utopian thinking in dangerous times: Critical pedagogy and the project of educated hope. Utopian pedagogy: Radical experiments against neoliberal globalization, 25-42.

Graham, C. & Lawrence, J. (2015). Building transcultural skills for professional contexts. In J.

Lawrence, C. Perrin, E. Kiernan, Professional Nursing Communication: Building professional nursing

communication (pp. 103-129). Port Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

Grant, J. & Luxford, Y. (2011). Culture it’s a big term isn’t it’?: An analysis of child and family health nurses’ understandings of culture and intercultural communication. Health Sociology Review: The Journal of the Health Section of the Australian Sociological Association, 20(1), 16-27.

Hamilton, J., Woodward-Kron, R. (2010). Developing cultural awareness and intercultural communication through media: A case study from medicine and health sciences. System, 38, 560-568. doi:10.1016/j.system.2010.09.015.

Hazelwood, Z. & Shakespeare-Finch, J. E. (2010). Let’s talk (listen feel think act) : Communication for health professionals. French’s Forest, Australia: Pearson Education

Hockley, N. (2012). Digital literacy. ELT Journal, 66(1), 108-112. doi:10.1093/elt/ccr077

Hunter, D. (2014). A practical guide to critical thinking: Deciding what to do and believe. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

International Council of Nurses[ICN]. (2012). The ICN code of ethics for nurses. Retrieved from https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/…/2012_ICN_Codeofethicsfornurses_%20eng.pd…

Kids Helpline. (2019). Retrieved from https://kidshelpline.com.au

Kitson, A., Marshall, A., Bassett, K., & Zeitz, K. (2012). What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine, and nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(1), 4-15.

Kossen, C, Kiernan, E &Lawrence, J(eds.) (2017). Communicating for success. Sydney, Australia: Pearson Australia.

Lankshear, C, Gee, P, Knobel, M & Searle, C (1997). Changing literacies. Buckingham, England:Open University Press.

Lawrence, J. (2014). The use of reflective, communicative and critical practices in facilitating international students’ transition to a regional Queensland university. Special Issue ‘Migration in Regional Queensland. Queensland Review, 21, 2.

Lawrence, J. (2015). Building lifelong learning capacities and resilience in changing academic and healthcare contexts. In J. Lawrence, C. Perrin, E. Kiernan, Professional Nursing Communication: Building professional nursing communication (pp. 48-69). Port Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

Luxford, Y. (2011).Culture is a big term isn’t it? An analysis of child and family health nurses understanding of culture and intercultural understanding. Health Sociology Review, 20,16–27.

Lytton, M. (2013). Health literacy: An opinionated perspective. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 45(6), 35-40. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.006.

Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. (2018). The code of conduct for nurses. Retrieved from https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/news/2018-03-01-new-codes.aspx

Queensland Government. (2019). Domestic and family violence. Retrieved from https://www.qld.gov.au/community/getting-support-health-social-issue/support-victims-abuse/domestic-family-violence

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1948). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Smith, A. (2014). Concepts of health and illness. In J. Dempsey, S. Hillege, & R. Hill (Eds.), Fundamentals of nursing and midwifery: A person centred approach to care (pp. 4 – 16). Sydney, Australia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. (1948). The international bill of human rights. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/compilation1.1en.pdf

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. (1976). International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx

Wikipedia (2006). The Johari Window. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johari_window

World Health Organisation. (2016). Health Literacy. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/9gchp/health-literacy/en/

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.1 Photograph by NeONBRAND on Unsplash © NeONBRAND is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 5.2 Transaction Model of Communication © Kossen, Kiernan & Lawrence, (2017), for the University of Southern Queensland. is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 5: 3 Photograph by rawpixel on Unsplash © rawpixel is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Figure 5.4 Model for Inclusive Practices © J. Lawrence, (2017), for the University of Southern Queensland. is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 5.5 Johari Window © Simon Shek (Wiipedia Author) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 5.5: Gibbs Reflective Cycle © GSE843 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 5.6 Photograph by youssef naddam on Unsplash © Youseff Naddam is licensed under a Public Domain license