4 Opening eyes onto inclusion and diversity in early childhood education

Michelle Turner and Amanda Morgan

What can educators do to create inclusive early childhood contexts that provide children and families with the opportunity to develop understandings of difference and diversity?

Key Learnings

- Diversity is a characteristic of early childhood education in contemporary Australia.

- The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child sets out the principle that all children have the right to feel accepted and respected.

- It is important that all young children have the opportunity to develop an appreciation and respect for the diversity of their local and broader communities.

- Adopting a holistic approach to diversity is promoted as a strategy for educators working in contemporary early childhood settings.

Introduction

In early childhood education, diversity and inclusion go together like “roundabouts and swings, a pair of wings, fish and chips, hops and skips, socks and shoes, salt and pepper, strawberries and cream, pie and sauce, the oo in moo” (McKimmie, 2010, p. 1). Effective early childhood educators understand that creating an inclusive learning environment that is responsive to a diverse range of characteristics and needs, can be a challenging and overwhelming endeavour with sometimes limited or underwhelming results (Petriwskyj, Thorpe & Tayler, 2014).

Traditionally, inclusive education in the mainstream early years classroom focussed on catering for children with special needs, such as physical impairment or autism, and for children considered ‘at risk’ or ‘disadvantaged’ in relation to issues such as socio-economic circumstances or geographical isolation (Petriwskyj, 2010). Petriwskyj’s (2010) research extends this notion of inclusive education to include many more considerations, such as the social, political, cultural, English as a second language, trauma-related and economic backgrounds of educational stakeholders.

This chapter is designed to reveal how early childhood educators could facilitate effective, inclusive pedagogies and programs in the mainstream classroom. Generally, when children have a diagnosed disability or a physical disability (such as needing a wheelchair or hearing aid), the general classroom teacher has access to support in the form of outside agencies or assisted technology (Forlin, Chambers, Loreman, Deppler & Sharma, 2013). However, when a teacher may think a child is ‘odd’, their learning progress is slow, or their behaviour is difficult to manage, then inclusive practices become difficult to seek, plan for and implement (Petriwskyj, 2010). The following information, ideas and activities are designed to be a general ‘teaching toolkit’ for new teachers to implement in a mainstream early childhood classroom to assist them to be more responsive and inclusive to its diverse clientele of students and families.

diversity

Diversity is a characteristic of early childhood education in contemporary Australia. Children engaging with early childhood contexts come from a range of social, economic, cultural and ability groups, and bring with them a considerable variation in life’s experiences. Diversity is defined by the Queensland Government Department of Education (2018) as encompassing individual differences such as culture, language, location, economics, learning, abilities and gender. Broader diversity constructs presented in the literature, such as diverse abilities (Ashman & Elkins, 2005), diverse learners (Coyne, Kame’enui & Carnine, 2007), diverse learning rights (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2006) and learners in diverse classrooms (Dempsey & Arthur-Kelly, 2007), highlight the complex and multi-dimensional nature of difference and the associated power relations of inequality (Ng, 2003). The representation of these constructs in the literature suggests a movement away from categorising children through ideas of normativity, to supporting learners with varied characteristics through differentiating pedagogies (Graham, 2007).

Australian society has become increasingly diverse in terms of the cultural and ethnic backgrounds, composition and size of families (Moore, 2008). Children’s developmental pathways are also more diverse. Taken for granted approaches about parenting and child development and traditional early childhood practices are challenged by this changing diversity (Fleer, 2003). Bronfenbrenner’s social ecology approach assists in the conceptualisation of the developing child in this changing diverse landscape because the model enables the recognition of “the broad range of contextual factors that can affect human development and education” (Odam et al., 2004, p. 18).

In the model, the child is situated at the centre of a number of concentric layers. These surrounding layers move out from the centre to reflect the varying contexts associated with the child at any given time in their life’s journey. Relationships between the child and surrounding layers are seen as dynamic.

Characteristics of the child such as age, health and personal traits, are embodied with the child in the centre of the model. The system closest to the child is called the microsystem and consists of the components in the child’s immediate surrounds such as family, extended family and early childhood setting. These components are seen to influence the child physically, socially, emotionally and cognitively. Emotional attachment with other people was viewed by Bronfenbrenner as a significant element in this layer (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The next layer of the model is called the mesosystem and refers to the alignment between contexts in the microsystem (Grace, Hayes & Wise, 2017). It is desirable for the child to experience high levels of alignment between the differing contexts experienced within their microsystem. A child who encounters a misalignment between the early childhood centre they attend and their family life may not be able to experience the best opportunities for learning. A strong match, however, between the values of the centre and their home life is likely to lead to improved learning outcomes.

The next adjacent layer, the exosystem, represents those systems or contexts that the child is not directly involved in but will still be impacted by. Parental employment, for example, can impact the child through such things as lower levels of income, higher working hours and increased stress levels. The final layer, the macrosystem, refers to the broad cultural and societal attitudes and ideologies that may influence components in all of the other systems. This layer represents the overall values of the society in which the child lives and is impacted by across all aspects life. Grace, Hayes and Wise (2017) provide the example of a society in which females are treated as being inferior to males by being denied equal access to education and employment, which may result in the female child possibly having reduced opportunities in life.

A final important point the Bronfenbrenner model makes, is that the child is not viewed as a static participant. The child is a dynamic being and influences the environment in which they engage. For example, parents of a child with vision impairment may make decisions about support mechanisms that the child has access to and bring these with them to the early childhood centre. Children, according to Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological model, will be influenced by, and will influence, their environment and the people in them (Grace, Hayes & Wise, 2017). Considering the child in their social, ecological surrounds can therefore assist educators in developing clearer understandings of children and their individual, unique diverse contexts.

inclusion

Ideas around inclusion in the early childhood field have evolved steadily over the past few decades, and are continuing to progress. This has occurred in a context of ongoing social change, which has been accompanied by similar changes across a range of social values and ideas. Definitions of inclusion traditionally focussed on readiness for assimilation into a general class (mainstreaming) (Petriwskyj, 2010) and integration in general classes with English language instruction and support for disability (Cook, Klein, & Tessier, 2008). These views have shifted to those incorporating curricular and pedagogic differentiation to support children’s senses of belonging (Gillies & Carrington, 2004). Changing values and ideas about diversity and difference, ability and disability, and social inclusion and exclusion in early childhood have been influential in this shift (Moore, Morcos & Robinson, 2009).

thinking about diversity and difference

Global populations are becoming more mobile, generating multi-cultural societies and therefore ethnic and cultural diversity in many world nations including Australia (Arber, 2005). Emerging from this is a growing awareness that everyone has their own cultural framework, which shapes perceptions, values and ideas (Gonzalez-Mena, 2004). Over (2016) notes that to experience personal growth and wellbeing, positive social interactions and long lasting relationships are necessary. Current thinking acknowledges the importance of incorporating children’s unique identities and diversities to enable positive experiences for personal growth and lifelong learning. Developing effective contexts for inclusion that support children manage their own needs in diverse and different multicultural group settings is therefore an important goal in an inclusive approach to diversity in early childhood settings.

Thinking about ability and disability

Diversity exists in the way children develop. Development in children occurs at different rates across a population. However, when children fail to comply with the developmental pathways typically outlined and expected in the school culture, they are sometimes labelled as having a developmental disability. Disability is an overall term defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2002) and incorporates three components:

1. Impairment, which refers to body functions (for example, sensory or cognitive functions) and body structures (for example, organ or limb functions)

2. Activity limitations, which refers to the challenges of carrying out daily activities such as self-care, mobility and learning.

3. Participation restrictions experienced as the child endeavours to participate within the family and community settings.

Reframed notions of the continuum of what is ‘normal’ have emerged in thinking around disability in recent years. . The impacts of social and environmental factors have come to be seen as additional components associated with disability and have led to challenging what is interpreted as normal. For example, the increased number of sites with wheel chair access has enabled wheel chair users to engage with a greater variety of facilities and therefore life experiences. Such inclusive actions works towards incorporating Article 23 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child which specifies that children with disabilities have the right to special care with assistance appropriate to their condition in order to promote the child’s social integration and individual development.

Thinking about social inclusion and exclusion

Developed nations have experienced social changes, which have not been beneficial for all members of society. Some people have failed to benefit from the changed social and economic conditions and instead have experienced social exclusion and therefore poorer outcomes (Hertzman, 2002). ). A report released by the Australian Early Development Census in 2015 revealed that one in five children who enter school in Australia are developmentally vulnerable in one or more domain, including cognitive skills and communication (Shahaeian & Wang, 2018). Social changes have resulted in the fragmentation of communities, greater demands on parents, and systems that are ill-equipped to cope with the needs of children and families (Moore & Fry, 2011). Social exclusion arises when children suffer from multiple factors that make it difficult for them to participate in society (Hertzman, 2002). These factors may include growing up in jobless households, being a member of a minority group or living with a sole parent. This may lead to the child being at risk of living in poverty and being socially isolated (Moore, Morcos & Robinson, 2009).

Whilst social inclusion may appear to be the opposite of social exclusion it incorporates much more. Social inclusion infers a proactive, mindful approach that requires action to facilitate conditions of inclusion (Caruana, & McDonald, 2018). Current understandings about child development and learning, as well as social justice and social inclusion, indicates that relationships, interactions and experiences in children’s early lives have a profound influence on early brain development and future life outcomes (Centre on the Developing Child, 2011; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). Reducing boundaries, barriers and social and economic distances between people are important when promoting a more inclusive society (Hayes, Gray & Edwards, 2008). To be inclusive it is vital that children and adults are able to participate as valued, respected and contributing members of society.

INCLUSION IN THE EARLY YEARS

According to Early Childhood Australia [ECA](2016), the peak early childhood advocacy body in Australia, “inclusion means that every child has access to, participates meaningfully in, and experiences positive outcomes from early childhood education and care programs” (p. 2). Inclusion is significant as: it incorporates current thinking around child development; implements the current mandated legal standards for early childhood education and care [ECEC]; supports children’s rights; and reflects quality professional practice (ECA, 2016). Additionally it needs to be recognised that acts of inclusion facilitate acceptance of diversity and the reduction of barriers that may preclude a child from achieving their fullest potential in an ECEC setting.

Inclusivity occurs when all children, regardless of their diversity, have equitable and genuine opportunities to participate in and learn from the everyday routines, interactions, play and learning experiences that occur in the early years (The State of Queensland [Department of Education and Training], 2017). A policy statement intended for all levels of schooling, including the early years, developed by the Queensland Government Department of Education (2018) states that:

Inclusive education means that students can access and fully participate in learning, alongside their similar-aged peers, supported by reasonable adjustments and teaching strategies tailored to meet their individual needs. Inclusion is embedded in all aspects of school life, and is supported by culture, policies and every day practices (p. 1).

Inclusive settings in the early years, according to the Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority [QCAA] (2014) sees that “educators strive to improve all learners’ participation and learning, regardless of age, gender, religion, culture, socioeconomic status, sexual preferences, ability or language. Inclusion encourages everyone in the community to participate and achieve” (p. 1). KU Children’s services who manage a range of inclusion support services for the Australian Governments Inclusion Support Programme created the following information sheet fact for educators and services about what Inclusion Is:

POLICY AND LEGAL REQUIREMENTS FOR INCLUSION IN THE EARLY YEARS

Early childhood contexts in prior to school settings in Australia are governed by the National Law and National Regulations which outline the legal obligations of approved providers and educators and explain the powers and functions of the state and territory regulatory authorities and the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority [ACECQA]. The Education and Care Services National Law (National Law) and the Education and Care Services National Regulations (National Regulations) detail the operational and legal requirements for an education and care service including most long day care, family day care, kindergarten/preschool and outside school hours care services in Australia.

The National Law and National Regulations are components of the National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care [NQF] which aligns with the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child by aiming to ensure that all children have the opportunity to thrive, to be engaged in civics and citizenship and opportunities to take action and be accountable (ACECQA, 2017). The NQF also “recognises all children’s capacity and right to succeed regardless of diverse circumstances, cultural background and abilities” (ACECQA, 2017, p.10). Inclusion is acknowledged as an approach in the NQF where educators recognise, respect and work with each child’s unique abilities and learning pathways and where diversity is celebrated (ACECQA, 2017). This approach of inclusive service delivery and practice is embedded in the national approved learning framework for early childhood settings; the Early Years Learning Framework [EYLF].

Additionally, the rights of children with disability and from diverse backgrounds to access and participate in ECEC services are set out in national and state based legislation such as:

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Commonwealth)

- Disability Standards for Education 2005 (Commonwealth)

- Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Queensland)

- Child protection Act 1999 (Queensland)

- Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Queensland)

Additional information around the legal requirements associated with diversity and inclusion is available by at the following link: Inclusion of children with disability

School settings in the Queensland context are also required to comply with legal requirements, in particular, the Education (General Provisions) Act 2006 (Qld) and state and commonwealth discrimination laws. To read further about these requirements click on the following link: Inclusive education

Additional Readings

To extend your understanding around policy and legal requirements in the early years access the following articles online through the USQ Library webpage:

- Miller, M. & Petriwskyj, A. (2013). New directions in intercultural Early Education in Australia. International Journal of Early Childhood, 45, 251-266. Doi: 10.1007/s13158-013-0091-4

- Petriwskyj, A., Thorpe, K., & Tayler, C. (2014). Towards inclusion: provision for diversity in the transition to school. International Journal of Early Years Education, 22(4), 359-379. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2014.911078

iNCLUSION BARRIERS AND MYTHS

Despite significant changes in thinking around diversity and inclusion, potential barriers to successful inclusion still exist. Barriers may serve to reduce the opportunities educators are prepared to take to design and create inclusive environments. The barriers can emerge from a range of issues including personal, attitudinal and organisational. From a personal perspective educators may be unwilling to engage with inclusion because of a perceived increase in workload or lack of confidence in their own skills to work with children with diversity. Personal bias and attitudes may impact upon the educator’s willingness to consider making adjustments to their program or to support children appropriately within their program.

Organisational systems and structures can create barriers for educators through such things as lack of leadership supporting inclusive practices, professional development for staff or finances for resources. Early childhood is a unique period, which provides the blueprint for all future development and learning. Where barriers exist, opportunities for children’s learning and development can be greatly reduced.

Myths associated with inclusion may also serve to dissuade the development of inclusive environments for all children. Dispelling myths associated with implementing inclusive practices through sound reflective practice, educator commitment and teamwork have been identified as starting points for successful inclusion. Livingston (2018) summarised myths under the following headings; the view that inclusion is not about disability, the perceived effects of including a disabled child in a classroom and the differences between inclusion and early intervention. Following is a discussion around these myths.

Inclusion is not just about disability

Ashman and Elkins (2005) note “inclusion enables access, engagement and success for all learners” (p. 65). The NQF promotes the valuing of diversity, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, people with a disability and people from diverse family compositions. The definition of inclusion in the approved learning frameworks for ECE is broader than simply providing for children with a disability. Inclusion is about embracing diversity, including every child holistically and providing opportunities for all children to participate and benefit.

As indicated above when discussing relevant policy and legal requirements, inclusion is a basic human right. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child states that all children have the right to an education (Article 28) that develops their ability to their fullest potential, prepares children for life and respects their family, cultural and other identities and languages (Article 29). This is reflected in Regulation 155 of the National Regulations where it states that an approved provider must take reasonable steps to ensure that the education and care service provides education and care to children in a way that maintains at all times the dignity and rights of each child.

Including a child with additional needs

There has been a perception by some that inclusion of diverse children will be detrimental to other group or class members. There is now sufficient evidence to suggest that peers are not harmed or disadvantaged through inclusive classrooms; rather, they grow and develop as a result of the relationships they cultivate and sustain with their diverse counterparts (Odom et al., 2004). Typically, developing children learn a great deal from their classmates in inclusive settings. The inclusion of children with disabilities prompts classmates to become more understanding of, and to develop positive attitudes toward, their diverse counterparts (Odom & Bailey, 2001).

Inclusive environments are characterised by repeated and impromptu interactions, which support all children in social, emotional and behavioural development (Odom et al., 2004). When children with disabilities or differing abilities attempt to engage their peers in social interaction, typically developing children with experience in inclusive environments respond to these initiations and progress relationships by initiating interactions, negotiating sharing and developing an understanding of other children (Odom et al., 2004). Additionally, children with experience of inclusive environments have been found to approach play with a stronger focus on fairness and equity and utilise more targeted ways to include diverse counterparts in their play (Diamond & Hong, 2010).

Research has found that children are most receptive to actions of inclusion at an early age. Evidence suggests that older children are less likely to be receptive of children with disabilities being included in academic settings (Siperstein, Parker, Bardon, & Widaman, 2007). Since inclusion is beneficial to all children, inclusion in early childhood settings is considered to be highly important (Gupta, Henninger & Vinh, 2014).

Inclusion and early intervention are not the same

Inclusion and early intervention for children with diversity are interrelated concepts but are viewed differently and have separate outcomes. As noted above the definition of inclusion in the EYLF refers to all children holistically. Early intervention relates to children who require additional support and involves the support of early childhood intervention specialists. The outcome of early intervention is to support children to develop the skills they need to take part in everyday activities and to be included in family and community life. This process is achieved in an inclusive environment where the important adults in the child’s life provide the experiences and opportunities necessary to help children participate meaningfully in their everyday lives.

Reflection

- Critically reflect upon these three myths.

- What can you add to the discussion?

- Have you experienced a change in your thinking?

INCLUSIVE PRACTICE

The image of the child

The starting point for successful inclusive practices is reflecting upon the image of the child. Loris Malaguzzi (1994) suggests that the educators’ image of the child directs them in how they talk, listen, observe and relate to children. The image of the child influences how the educator views the child and influences their expectations they have of them. Reflecting on the image of the child shifts the focus back to the child as they are, not just the way they are perceived or labelled.

The image of the child promoted by advocates of inclusive practices, presents the child as being so engaged in experiencing the world and developing a relationship with the world, that he or she develops a complex system of abilities, learning strategies and ways of organising relationships (Rinaldi, 2013). Children are the “bearer and constructors of their own intelligences”, expressing their leanings in a variety of ways; a process Reggio educators refers to as ‘the hundred languages’ (Rinaldi, 2013). Underlying the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (2010) is the belief that children are competent and capable of actively constructing their own learning.

Reflection

- What is your image of the child?

- Do you see the child’s competencies and complexities?

- Is this a child who shares their thinking, theories and wonderings with you or do they censor themselves in adult child interactions?

Getting to know the children

It is important to get to know individual children so that the appropriate support can be offered to them. This is most successfully achieved through discussion with the family and the child and through observation and documentation. Discussions with the family will provide educators with vital information about the child. It is important to ask questions with sensitivity and understanding in talks with parents and to set a tone of welcome for the family that encourages communication and open discussion built on trust and respect.

Conversing with the child about their abilities, needs, and interests empowers the child and increases their sense of agency. Conversations provide the opportunity for the child to verbalise their interests and needs. Observations are a vital tool for early childhood educators to build an understanding of children’s interests, abilities, learning, development and wellbeing (Colville, 2018). When observing an individual child, it is important to focus on the child’s abilities. Looking beyond a textbook definition of their possible diversity and noting their strengths and what they can do is also helpful. Documenting observations of children professionally and regularly, without labels or diagnoses is also a useful step. Interpreting these observations and applying this information when making decisions about programming and planning that relate to individual children and groups of children is also effective in building an inclusive culture.

Early childhood educators are key in knowing and understanding child development. Understanding that children learn skills in a particular order will help the early childhood educator set realistic expectations for the child’s skill development. As an example a child needs to practice standing before practicing walking. A child with special needs may need to have a skill divided into smaller steps before the skill can be mastered.

The following e-Newsletter provides practical ideas for learning about children’s knowledge, ideas, culture and interests through observation. Click on the following link to access the information sheet: NQS PLP e-Newsletter No. 39 2012 – Observing children

Inclusive environments

The importance of high quality early years education and care has been well documented (Dahlberg, Moss, & Pence, 2007; Dearing, McCartney & Taylor, 2009; Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2014; Sylva, 2010, Torii, Fox & Cloney, 2017). Participation in inclusive high-quality early childhood settings is fundamental to supporting children to build positive identities, develop a sense of belonging and realise their full potential. Supporting children’s positive individual and group identity development in ECEC is fundamental to realising children’s rights. Inclusive environments provide the space for the recognition of gender, ability, culture, class, ethnicity, language, religion, sexuality and family structure as integral to society (Queensland Government Department of Education, 2018b).

Carefully planned environments engage and enable children to co-construct learning and build deeper understandings (Queensland Studies Authority, 2010). The educator’s image of a child and the environment they create are strongly connected. Creating an environment that supports the inclusion of every child means each child can be supported to thrive and build a respect and valuing of diversity. High quality education and care is characterised by thoughtfully designed environments that support intentional, structured interactions to scaffold children’s growth and learning. Quality child-care contributes to the emotional, social, and intellectual development of children.

A starting point in creating an inclusive environment is to pay close attention to the physical environment. Does the physical environment meet the needs of the children and support children to engage naturally with things that interest them? Physically inclusive spaces maximise each child’s opportunity to:

- access and explore indoor and outdoor areas as independently as possible;

- make choices about the resources they access and the experiences they participate in;

- interact meaningfully with other children and adults;

- care for themselves as independently as possible;

- experience challenge and take managed risks;

- engage with images, books and resources that reflect people with disabilities as active participants in and contributors to communities in a variety of ways (Owens, 2012, p. 2).

When adapting the physical environment to include a child with a disability, it is important to consider what needs to be altered or added to enable the child to manage daily routines and experiences as independently as possible. How accessible are the resources for the child? Do items need to be placed at a different height or level so that the child can reach them? Considering issues of fairness and equity at the level of the individual child and the group and providing appropriate adaptations that allow diverse children to participate in the classroom curriculum is an effective strategy as well (Diamond & Hong 2010). Attention to the physical demands of daily classroom activities for example may support classroom wide intervention (Brown, Odom, McConnell, & Rathel, 2008). For example, moving a painting activity from an easel to a tabletop for all children may offer support for those who find it difficult to stand and paint for long periods (Sandall & Schwartz, 2008).

Adaptations to the indoor and outdoor environments that increase children’s access to activities might be effective in supporting peer interaction (Diamond & Hong 2010). For example, a child with a communication difficulty may benefit from using visual resources such as pictorial flow charts to help them understand and participate in the day’s routines and activities (Owens, 2012). Inviting all children to become familiar with the visual resources and encouraging them to support those who are unsure is another useful strategy. A child who experiences high levels of anxiety or behavioural issues may need a safe, quiet area to go to when they feel overwhelmed or want time away from the group (Owens, 2012). Such additions to the environment often benefit all children.

It is beneficial to include strategies that support children’s independence as they access the class resources to undertake their learning. Educators in classrooms make use of a large variety of ideas and strategies to enable learner’s independence. Visit the resource below and make a note of the different ideas one teacher has used to create an inclusive prep classroom in a Queensland primary school. Use these ideas to begin your own collection of strategies and build upon the list as you continue to engage with ideas around creating inclusive classrooms.

Cultural competence

In creating an inclusive physical environment, a shared culture of inclusion can be modelled and supported. Children are naturally curious about the people around them as they attempt to develop a sense of their own identity. One way of achieving this is by defining what makes them different from everyone else. A child may ask questions about observable characteristics like skin colour, accent, or manner of dress. “Children are around two or three when they begin to notice physical differences among people” (Kupetz, 2012, p. 1). Questions about characteristics such as “Why is Kiah’s skin brown?” are not motivated by any intention to offend or hurt. Educators can use these opportunities to send a fair and accurate message about each diversity, so that children learn that these differences make a person unique. The educator can utilise these encounters with diversity to enrich all children’s learning.

In this podcast the educator took the opportunity to support children to become familiar with, understand and experience being different. Families NSW (2011) recommend simple examples to embrace diversity within an early childhood setting:

- Make a point of acknowledging where all the children in the group come from by simply hanging a map and tagging locations with the child’s name and country of origin.

- Showcase a country each week or month and take the opportunity to invite parents to share words or phrases from their language, songs, music, food, traditional dance and costumes.

- Celebrate culturally diverse calendar events throughout the year.

- Display and make accessible multicultural and multilingual resources.

However, it is not enough just to raise cultural awareness. It is a requirement of the NQF for educators to become culturally competent. Cultural competence is about thinking and actions that lead to:

- Building understanding between people;

- Being respectful and open to different cultural perspectives;

- Strengthening equality in opportunity (ACECQA Newsletter, 2014).

Read more about developing cultural competence through the We Hear You newsletter published by ACECQA.

Intentional teaching

In the Early Years Learning Framework, the term ‘intentional teaching’ is used to describe teaching that is purposeful, thoughtful and deliberate (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. (2009). In this definition it is the word intentional that is important since it assumes that an intentional educator is someone whose actions stem from deep thoughtfulness where the potential effects have been considered (Epstein, 2007). Epstein goes on to point out that this means the educator understands why they are doing what they are doing (the intentional act) and what strategy is required for the teachable moment.

A number of effective intentional environmental strategies to support interactions among children with disabilities and their classmates without disabilities include limiting the size of groups and using materials that are familiar and likely to encourage social interactions. Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) 2017) have suggested the following strategies for applying intentional teaching practices within inclusive environments.

Model appropriate behaviours

Children learn through observation and imitation (Meltzoff, 1999) and modelling by an educator becomes a powerful tool in intentional teaching. Children notice when adults are working and collaborating together and modelling positive behaviours. Children imitating this modelled adult behaviour will demonstrate considerate actions that support an understanding of inter-dependence both within and outside of an early childhood setting.

Using a range of communication strategies

Children cannot always find the appropriate words to use to express how they feel especially when they are faced with something outside of their normal experiences. Introduce and use a wide range of communication strategies with all children to equip them with a variety of approaches to use when they attempt to organise their own feelings, explain events and resolve conflict. A variety of communication strategies may include gestural, pictorial, oral and written components. It may be necessary at times to “give” the children the appropriate words to use. For example, in the following scenario the educator helped Sam express his thinking, using words:

Scenario

Sandpit play:

Sam is building a road in the sand using a spade and a trowel. He puts the spade down as he picks up the trowel. Peter turns around and takes the spade. Sam immediately pushes Peter over and takes the spade back. The educator checks that Peter is OK and then says to Sam. “I can see that you are still using the spade but Peter did not see that. Could you please say to Peter “I am still using the spade”? Sam repeated the words and Peter nodded his head turning back to his own sand construction.

Using self-talk

Using self-talk can be a powerful form of guidance for children. Educators can ‘self- talk’ through activities with which they are engaged, so that they are giving children a commentary on their actions. For example, ‘I am cutting around the picture. I am trying to be careful and make the scissors stay on the line’. Educators can also ‘parallel talk’ as they provide commentary on what the child is doing. Both strategies can be very helpful for short periods but should not be extended to the point where they become intrusive or inhibiting.

Be firm when necessary

Children need the security that comes with knowing that there are limits and that when they need help with their behaviour they will get it. Children need adults to set reasonable boundaries and help them to organise their feelings and responses. Educators can support children to focus on the outcomes of being considerate to others while searching for a fair and equitable resolution that supports children’s learning.

Acknowledge considerate behaviour

Let children know when they do things that you want to see more of. Try to support children to manage their own behaviour in a way that tells the child “I know this is hard for you, but I will help you”. Modelling empathy provides children with a repertoire of examples and strategies to use themselves.

The emphasis is on supporting children to manage their own behaviour in a ways that teach and show respect. When responding to a child’s behaviour it is important to make sure you are doing so in ways that maintains their dignity and rights. In order to do so, it is important to take a moment and reflect on the best way to respond, rather than simply react, however in some situations educators may need to respond quickly if safety is an issue.

High Expectations

Every child is unique. Children may share the same type of disability, but be completely different from each other in every other respect. While there are some exceptions many two year olds with special needs have, for example, they will also face the same challenges of being two that all children face. Setting high expectations for each individual child is vital to their overall success.

Promoting inclusion and the participation of all children across the entire program involves working with each child’s unique qualities and abilities, strengths and interests, so that each child can reach his or her potential. Early childhood professionals are key in knowing that children with special needs are more like all children than different. Where and when possible setting similar expectations for children will help them to be accepted. High expectations of all children can be delivered through flexible program approaches and curriculum decision making, focused on inclusive practice. Curriculum decision making for inclusion of children with a disability is about creating opportunities for all children to engage in daily experiences, rather than planning alternative or separate experiences for a particular child (Owens, 2012). Curriculum considerations includes all planned and unplanned “interactions, experiences, routines and events” that occur each day (ACECQA, 2011, p. 203). When undertaking inclusive curriculum decision making, educators intentionally extend each child’s learning by designing experiences that build on the child’s “strengths, interests and abilities in both planned and spontaneous learning experiences” (Owens. 2012, p. 2).

Involving families

Families of children with diversity have the same needs for ECEC as do other families. Inclusive ECEC environments offer all families the opportunity to engage in regular life patterns (Jansson & Olsson, 2006). Offering inclusive settings removes barriers and provides the opportunity for all children to engage in high quality ECEC that may enhance their learning and developmental success.

Be clear and transparent

At the outset inform all families about the setting’s philosophy in regard to inclusion and diversity. When educators and families have different views regarding this, the educator may need to seek support from colleagues and draw on the centre policies for guidance. A focus on the holistic, inclusive approach of the NQF will be of assistance here.

Pay attention to settling-in

Every family can face challenges when settling into a new ECEC setting, as each child must adjust from their home culture to the culture of the service. Children from different backgrounds, minority groups or a child with a disability may face an extra challenge as they undergo this transition from their home to the setting. The cultural and educational approach of the setting, which is generally based on the values and perspectives of the majority population, may be new to families. It is essential that such families feel confident that the settling-in process will support, and be appropriate to, their child’s needs.

Support families when asked

Educators play an important role in helping families support and guide their child’s learning and development in positive and effective ways. When families are well-supported by educators they may be better equipped to nurture their child’s learning and development (Hunter Institute of Mental Health, 2014). Families may need support, and educators need to respond in non-judgemental ways. As with so many areas of communication and relationships, it helps if the educator can put themselves in the shoes of the family and think about how they (the educators) may feel in the same situation. Developing collaborative partnerships that involve respectful communication about all aspects of a child’s learning and development helps both parties to adopt a holistic and consistent approach. Taking a professional approach supports educators in presenting a positive attitude to families, working collaboratively to identify options to solve problems.

Providing the family with professional advice about their child’s learning and development, including their strengths and their psychological, social and emotional development is important. Families do not always know where to go to for assistance to act on the information provided. Recommending reliable sources of information and support for families in their local community and beyond is vital. The early childhood educator regularly serves as the conduit between families in need and agencies structured to assist. Educators with a sound knowledge of the variety of support systems available for the community group associated with the ECEC setting is best equipped to be of assistance here.

Communicate with families

It is important that educators identify children’s learning needs and respond quickly to any concerns they may have. Communicating concerns about a child to the parents is often a difficult step. Success is more likely if this step is taken from an already-existing relationship that is built on trust and respect. Even when this relationship is in place, educators need to plan what they will say about concerns for the child. A discussion of this nature should take place in a private location, with adequate time allowed, and, if applicable, both parents in attendance.

The first step is to ask the family members how they see the child and then to share the positive qualities observed within the ECEC setting. At the outset, it is helpful for educators to let the family know that:

- They share concerns for the child.

- Their intent is to support the child’s development.

In order to do this, educators need to get some ideas for how to best meet the child’s needs. If family members differ in their view of the child, be open to their perspective, ask questions, gather information, and invite them to be your partner in meeting the needs of their child. When done respectfully, this communication can lead to a fruitful exchange of ideas and ultimately help for the child. The following document provides practical ideas for communicating with parents effectively in ECEC settings. Click on the following link to access the information sheet: Kids Matter – Effective Communication between families and staff members

Negotiate multiple agency involvement

While in an early childhood program, children with special needs may receive additional therapy from specialists. Early childhood professionals are key in partnering with the family and other professionals in the provision of support services for the child. Communication with those providing specialist support helps to coordinate the activities of the child. Educators play an important role in working with parents to support their children.

Successful engagement between educators, families, professionals, agencies and community members enable the sharing of information that ultimately support children’s learning and development. Strong partnerships between these sites also help vulnerable children feel more secure (Hunter Institute of Mental Health, 2014). By working with families, professionals and agencies, educators may have access to helpful information and strategies to manage or guide children’s learning and development.

Empowering Children

Educators who enact thoughtful and informed curriculum decisions and work in partnership with families and other professionals provide children with the greatest opportunity for success. Enabling child agency through considered curriculum and program design empowers children to engage confidently with their own learning and development. By purposefully planning experiences and engaging in nurturing, non-directive interactions with children, staff can optimise children’s learning. Supporting children’s agency enables them to make choices and decisions, and influence events and their world. Appropriate choices provide children with an opportunity to implement their emerging skills and develop a strong sense of identity. A practical strategy is to implement strategies, practice and programs that support every child to work with, learn from and help others through collaborative learning opportunities.

It is important to acknowledge children as individuals with a range of skills, emotions and experiences, both at home and at the setting, that may impact on how they cope being part of a group setting on any given day. Children’s learning is most effective when staff members are responsive and make the most of the spontaneous skill learning opportunities that arise in children’s everyday experiences. For children to learn to guide their own behaviour they need help to understand expectations and what is acceptable. For example, they may not understand why they have to wait to use the new equipment; why they cannot draw on the walls; why it is not appropriate to pull someone’s hair to get them to move. The answers to these questions are not always obvious to children. Empower children by acknowledging their understandings and supporting them as they develop new knowledge.

Play-based Pedagogy as a Tool for Inclusive Education and Diversity

ECEC settings serve a wide range of children with various needs, backgrounds, abilities, genders, cultures, languages, and interests. Play based learning experiences are at the heart of early education (Booth, Ainscow & Kingston, 2006). Children make sense of their world through their play and engage in the social world of their peers when they are playing. They benefit from the opportunities play offers to make decisions, predictions and solve problems. Where children are supported in play, they actively interact with others to create experiences to develop the skills and rewarding relationships that are fundamental to their personal growth and development across physical, social, emotional and cognitive domains (KidsMatter, n.d.). They create valuable learning opportunities for themselves through their interactions with their world and the people in it (Siraj-Blatchford & Sylva, 2004). Children learn to transfer their social and emotional skills and understandings to new situations through play and interactions with their peers.

Shipley (2013) suggests the following principles relating to learning through play. Children learn:

• when given plenty of opportunities for sensory involvement.

• through exploration and experimentation where they are free to move and pursue self-paced activities at their individual developmental level.

• by doing and interacting with real objects in a playful learning environment.

• most effectively if they are interested in what they are learning and free to choose to play in their own way.

• in an environment where they experience psychologically safety, a place where risk taking and mistake making are acceptable and where encouragement is offered in a timely manner that supports a learning moment.

• by uncovering concepts through open-ended exploratory play.

• most effectively when they progress from concrete to abstract concepts involving simple to more complex levels of knowledge, skill, and understanding, and where they can make sense of general concepts through to specific concepts.

• by revisiting prior knowledge, previously acquired skills, and concepts in manner that reinforces the transference of knowledge from a known context to application in a new context.

• most effectively when their experiences of play build on what they already know, and can take one step further, what is known as a zone of proximal development at a pace that is scaffolded to suit the

individual.

Play-based pedagogy is well suited to supporting diversity and inclusive education, as it incorporates the interests, insights and backgrounds of all the children (Siraj-Blatchford & Sylva, 2004). Educators who embrace a play-based pedagogy are responsive to the individual strengths and needs of children, which lead to a naturally inclusive environment (McLean, 2016). Within a play-based learning environment, educators have the opportunity to adapt the environment and resources routinely to promote optimal learning experiences for all students based on individual development, interests, strengths and needs. Educators are key in encouraging children to be independent. Children like to do things on their own and it is better for the development of children, to encourage them to do whatever they can for themselves. A play-based setting supports this approach.

The role of the educator is integral to supporting children’s learning and development. Educators provide support (i.e., scaffold) to extend the duration and complexity of children’s play as well as encourage children to incorporate language, literacy, and numeracy within their play (McLean, 2016). When teachers consider individual children’s abilities, interests and preferences, they create an environment that is engaging for all.

To support all children to learn and develop through play, Wood (2007) suggests educators:

• plan, resource and create challenging learning environments;

• support each child’s learning via intended play activity;

• extend and support play that is spontaneous;

• develop and extend each child’s communication in play;

• assess each child’s learning through play promoting continuity and facilitating progression;

• combine child-initiated play with adult-directed activities;

• accentuate well-planned, purposeful play in both outdoor and indoor settings;

• plan for connection between work and play activities;

• provide time for children to engage deeply in work activities; and

• scaffold opportunities for engagement connecting children and adults.

When enacting play-based pedagogies educators are able to recognise the discoveries being made by children as they construct their own knowledge, in their own ways (McLean, 2016). Curriculum objectives will be met in an integrated program, allowing for depth as well as breadth as children make meaning from the world around them. Play-based approaches open a setting to all learning possibilities in a way that inclusion happens as part of every-day life and diversity is welcomed and celebrated.

conclusion

It is the right of every child to be provided with the opportunity to learn and develop to the best of their ability. Early childhood educators are required to facilitate effective, inclusive pedagogies and programs in the both childcare and school settings to cater for the diverse children and families who may attend their site. Strategies and ideas for developing diverse classrooms have been suggested in this chapter.

Conclusion Activity

Managing inclusivity within your classroom will require flexible and creative approaches. Reflecting upon the information provided above prioritise 5 approaches you will utilise to create a more inclusive environment. Use resources such as those provided via the websites below to begin your list.

Resources for educators

Recommendations for best practice for early childhood educators in Queensland state schools (Prep teachers) are as follows:

1. Build relationships. The Early Years Learning Framework Practice Based Resources – Connecting with families: Bringing the Early Years Learning Framework to life in your community (for more information, refer to https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/connecting-with-families_0.pdf) offers practical advice for early childhood practitioners. PACE attitude training, offered in Queensland by Evolve Therapeutic Services, is a valuable resource for teachers working with children who have experienced trauma or neglect (for more information refer to https://www.communities.qld.gov.au/childsafety/partners/our-government-partners/evolve-interagency-services).

2. Connect with culture. Non-indigenous teachers should seek access to safe, reliable cultural cues from other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff within their school or wider community (Dockett, Perry & Kearney, 2010; Lewig et al., 2010; Zon et al., 2004). Professional practice should also reflect other minority cultures represented in the school’s student population (Cortis et al., 2009; Gilligan & Akhtar, 2005; Hundeide & Armstrong, 2011; Libesman, 2004; Ryan, 2011).

Refer to the Foundations for Success website for further information https://det.qld.gov.au/earlychildhood/service/Documents/pdf/foundations-for-success.pdf#search=crossing%20cultures%20training%20teachers. Also, Queensland state school teachers can access Crossing Cultures and Hidden History training – for more information, refer to http://indigenous.education.qld.gov.au/school/crossingcultures/Pages/default.aspx

3. Manage behaviour effectively. Use real and life-like examples to role-model socially-acceptable responses, reactions and reflections to everyday situations (Doyle, 2012; Howe, 2005). Establish and maintain routines, timetables and rewards systems (Gross et al, 2006; Karr-Morse & Wiley, 1997). The Positive Behaviour for Learning (PBL) behaviour management approach is currently being implemented in Queensland state schools (refer to http://behaviour.education.qld.gov.au/Pages/default.aspx) and is recommended for children with challenging behaviours (DET, 2015; Umbreit & Ferro, 2015).

4. Access help and support at a school level. Queensland state schools have access to specialists including speech/language pathologists, behaviour coaches, occupational therapists, guidance officers and learning support teachers (refer to https://education.qld.gov.au/students/students-with-disability/specialist-staff for more information). Contact the school’s Principal if there are extended absences or a suspected case of child abuse or neglect (refer to https://oneportal.deta.qld.gov.au/Students/studentprotection/Pages/Studentprotectionprocedureandguidelines.aspx for further information). A wraparound approach to support is preferred (Cortis et al., 2009). This could include the school’s collaboration and cooperation with different community-based support agencies (Cortis et al., 2009 The HIPPY (for more information, refer to http://hippyaustralia.bsl.org.au/) and FAFT (Families as First Teachers) programs (for more information refer to http://www.earlyyearscount.earlychildhood.qld.gov.au/age-spaces/families-first-teachers/) assist families with young children to develop the language and interactions which best support parent-child relationships and a child’s transition to school (Dean & Leung, 2010). Working with families is viewed as best practice for educators, parents and ‘at risk’ children (DiLauro, 2004; Karr-Morse & Wiley, 1997).

5. Supporting children with additional needs. Early Years Connect is a website developed by the Queensland Government Early Childhood Education and Care section of the Department of Education. The purpose of the site is to help educators support children with complex additional needs to participate in early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings. The resources include information sheets, online modules and webinar recordings.

6. Complex and additional needs. The Early Years Health and Development website developed by the Queensland Government Department of Education provides to a number of links for supporting inclusive practice in early childhood settings along with links to information around health and development issues.

referenceS

Arber, R. (2005). Speaking of race and ethnic identities: Exploring multicultural curricula.Journal of Curriculum Studies 37(6), 33–652. doi: 10.1080/00220270500038586

Ashman, A., & Elkins, J. (2005). Educating children with diverse abilities(2nd ed.). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson.

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2017). Guide to the National Quality Framework. Sydney, NSW: ACECQA.

Booth, T., Ainscow, M., & Kingston, D. (2006). Index for inclusion: Developing play, learning and participation in early years and childcare. Bristol: Centre for Studies in Inclusive Education.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brown, W., Odom, S., McConnell, S., & Rathel, J. (2008). Peer interactions for preschool children with developmental difficulties. In W. B. Brown, S. L. Odom, & S. R. McConnell (Eds.), Social Competence of Young Children with Disabilities: Risk, Disability, and Intervention(pp. 141-164). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Centre on the Developing Child. (2011). Building the brain’s air traffic control system: How early experiences shape the development of executive function.Working Paper No. 11. Retrieved from http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu

Caruana, C., & McDonald, M. (2018) Social inclusion in the family support sector. (online) Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Family Services. Retrieved from: https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/social-inclusion-family-support-sector/export

Colville, M. (2018). Observation-based planning. Chap 11 pg 319-354. In Estelle Irving & Carol Carter, The Child in focus: Learning and teaching in early childhood education pp. 319-354). South Melbourne, VIC: Oxford Press.

Coyne, M., Kame’enui, D., & Carnine, D. (2007). Effective teaching strategies that accommodate diverse learners. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Dahlberg, G., Moss, P., & Pence, A. (2007). Beyond quality in early childhood education and care: Languages of evaluation (2nd ed.). London, England: Falmer Press

Dearing, E., McCartney, K., & Taylor, B. (2009). Does higher quality early child care promote low-income children’s math and reading achievement in middle childhood? Child Development, 80(5), 1329-1349. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01336.x

Dempsey, I., & Arthur-Kelly, M. (2008). Maximizing learning outcomes in diverse classrooms. South Melbourne, Victoria: Thomson.

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. (2009). Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Commonwealth of Australia.

Diamond, K., & Hong, S. (2010). Young children’s decisions to include peers with physical disabilities in play. Journal of Early Intervention, 32, 163–177.

Epstein, A. (2007). The intentional teacher. Choosing the best strategies for young children’s learning. Washington, D.C: NAEYC.

Families NSW. (2011). Celebrating cultural diversity in early childhood services.(Tip Sheet 2). Retrieved from http://www.resourcingparents.nsw.gov.au/ContentFiles/Files/diversity-in-practice-tipsheet-2.pdf

Forlin, C., Chambers, D., Loreman, T., Deppler, J., & Sharma, U. (2013). Inclusive education for students with disability: A review of the best evidence in relation to theory and practice.Retrieved from https://www.aracy.org.au/publications-resources/area?command=record&id=186 (2013).

Fleer, M. (2003). Early childhood education as an evolving ‘Community of Practice’ or as lived ‘Social Reproduction’: Researching the ‘taken-for-granted’. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 4(1), 64-79.

Gillies, R., & Carrington, S. (2004). Inclusion: Culture, policy and practice: A Queensland perspective. Asia-Pacific Journal of Education, 24(2), 117–28.

Gonzalez-Mena, J. (2004). Diversity in early education programs: Honouring differences(4th Ed.). Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill College.

Grace, R., Hayes, A., & Wise, S. (2017). Child development in context. In R. Grace, K. Hodge &C. McMahon (Eds.), Children, families and communities (5thed.) (pp. 3- 25). South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press

Graham, L. (2007). Done in by discourse… or the problem/s with labelling. In M. Keefe & S. Carrington (Eds.), Schools and diversity (2nd ed.)(pp. 46-53). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson.

Gupta, S., Henninger, W., & Vinh, M. (2014). First steps to preschool inclusion: How to jumpstart your program wide plan.Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Hayes, A., Gray, M., & Edwards, B. (2008). Social inclusion: Origins, concepts and key themes.Canberra, ACT: Social Inclusion Unit, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. http://www.socialinclusion.gov.au/publications.htm

Hertzman, C. (2002). Leave no child behind! Social exclusion and child development. Toronto, Ontario: The Laidlaw Foundation.

Hunter Institute of Mental Health. (2014). Connections: A resource for early childhood educators about children’s wellbeing. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Department of Education.

Jansson, B., & Olsson, S. (2006). Outside the system: Life patterns of young adults with intellectual disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 8(1), 22-37. doi:10.1080/15017410500301122

KidsMatter. (n.d.). Early Childhood: A framework for improving children’s mental health and wellbeing.Retrieved from https://www.kidsmatter.edu.au/early-childhood/kidsmatter-early-childhood-practice/framework-improving-childrens-mental-health-and

Kupetz, B. (2012). Do you see what is happening? Appreciating diversity in early childhood settings. (Online). Early Childhood News. Retrieved from http://www.earlychildhoodnews.com/earlychildhood/article_view.aspx?ArticleID=147

Livingstone, R. (2018, April 30). Breaking down the inclusion barriers and myths. (We Hear You Blog). Retrieved from: https://wehearyou.acecqa.gov.au/2018/04/30/breaking-down-inclusion-barriers-and-myths/

Malaguzzi, L. (1994). Your image of the child: where teaching begins.Child Care Information Exchange (96), 52-61.

Meltzoff, A. (1999). Born to learn: What infants learn from watching us. In N. Fox & J.G. Worhol (Eds.), The role of early experience in infant development(pp. 1-10). Skillman, NJ: Pediatric Institute Publications.

McKimmie, C. (2010). Two peas in a pod. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin

McLean, C. (2016). Full–day kindergarten play-based learning: Promoting a common understanding.Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Retrieved from: https://www.ed.gov.nl.ca/edu/pdf/FDK_Common_Understandings_%20Document_Eng_2016.pdf

Moore, T. (2008). Supporting young children and their families: Why we need to rethink services and policies. (CCCH Working Paper No. 1). Parkville, Victoria: Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and The Royal Children’s Hospital Centre for Community Child Health. Retrieved fromhttp://www.rch.org.au/emplibrary/ccch/Need_for_change_working_paper.pdf

Moore, T. & Fry, R. (2011). Place-based approaches to child and family services: A literature review. Parkville, Victoria: Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and The Royal Children’s Hospital Centre for Community Child Health.

Moore, T., Morcos, A., & Robinson, R. (2009). Universal access to early childhood education: Inclusive practice – kindergarten access and participation for children experiencing disadvantage. (Background paper). Parkville, Victoria: Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and The Royal Children’s Hospital Centre for Community Child Health. Retrieved from https://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/ccch/UAECE_Project_09_-_Final_report.pdf

Ng, R. (2003). Towards an integrative approach to equity in education. In P. Trifonas (Ed.), Pedagogies of difference: rethinking education for social change(pp. 206-219). (New York, NY: Routledge Falmer)

Odom, S., & Bailey, D. (2001). Inclusive preschool programs: Classroom ecology and child outcomes. In M. Guralnick (Ed.), Early childhood inclusion: Focus on change(pp. 253–276). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Odom, S., Vitztum, J., Wolery, R., Lieber, J., Sandall, S., Hanson, M., Beckman,P., Schwartz, I., & Horn, E. (2004). Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective. Journal of Research in Special Education Needs, 41, 17–49.

Over, H. (2016). The origins of belonging: Social motivation in infants and young children. Philosophical Transactions Royal Society Publishing B, 371, 1-8. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.007220150072.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2006). Starting strong 11: Early childhood education and care. Paris, France: OECD.

Owens, A. (2012). Curriculum decision making for inclusive practice. National Quality Standard Professional Learning Program, 38, 1-4. Retrieved from: http://www.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/nqsplp/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/NQS_PLP_E-Newsletter_No38.pdf

Peisner-Feinberg, E., Buysse, V., Fuligni, A., Burchinal, M., Espinosa, L., Halle, T., & Castro, D. (2014). Using early care and education quality measures with dual language learners: A review of the research. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29, 786-803. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.04.013

Petriwskyj, A. (2010). Diversity and inclusion in the early years. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(2), 195-212. doi: 10.1080/13603110802504515

Petriwskyj, A., Thorpe, K., & Tayler, C. (2014). Towards inclusion: provision for diversity in the transition to school.International Journal of Early Years Education, 22(4), 359-379. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2014.911078

Queensland Government Department of Education. (2018). Inclusive Education Policy. Retrieved from https://education.qld.gov.au/students/inclusive-education

Queensland Government Department of Education. (2018b). Respect for diversity. Retrieved from https://qed.qld.gov.au/earlychildhood/about-us/transition-to-school/information-schools-ec-services/action-area-research/respect-for-diversity

Queensland Studies Authority. (2010). Queensland kindergarten learning guideline. Brisbane, QLD: Author

Rinaldi, C. (2013). Re-imagining childhood. Adelaide, SA: Government of South Australia.

Sandall, S., & Schwartz, I. (2008). Building blocks for teaching preschoolers with special needs. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Shahaeian, A., & Wang, C. (2018). More children are starting school depressed and anxious – without help, it will only get worse. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/more-children-are-starting-school-depressed-and-anxious-without-help-it-will-only-get-worse-87086

Shipley, D. (2013). Empowering children: Play-based curriculum for lifelong learning. Toronto, ON: Nelson Education.

Shonkoff, J., & Phillips, D. (Eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development.Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Siperstein, G., Parker, R., Bardon, J., & Widaman, K. (2007). A national study of youth attitudes toward the inclusion of students with intellectual disabilities. Exceptional Children, 73(4), 435–455.

Siraj-Blatchford, I. & Sylva, K. (2004). Researching pedagogy in English pre-schools. British Educational Research Journal, 30(5), 713-730.

Sylva, K. (2010). Introduction: Why EPPE? In K. Sylva, E. Melhuish, P. Sammons, I. Siraj-Blatchford, & B. Taggart (Eds.), Early childhood matters: Evidence from the effective pre-school and primary education project (pp.1-7). Abingdon, England: Routledge.

The State of Queensland (Department of Education and Training) (2017). Early Years Connect: The principles of inclusion. (Information sheet 2). Retrieved from https://qed.qld.gov.au/earlychildhood/service/Documents/pdf/info-sheet-2-principles-inclusion.pdf

Torii, K., Fox, S., & Cloney, D. (2017). Quality is key in Early Childhood Education in Australia. (Mitchell Institute Policy Paper No. 01/2017). Melbourne, Victoria: Mitchell Institute. Retrieved from:www.mitchellinstitute.org.au

World Health Organization (WHO). (2002). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

Wood, E. (2007). New directions in play: Consensus or collision? Education 3-13, 35(4), pp.309-320. doi: 10.1080/03004270701602426

Yazejian, N., Bryant, D., Freel, K., & Burchinal, M. (2015). High-quality early education: Age of entry and time in care differences in student outcomes for English-only and dual language learners. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 32(1), 23–39. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.usq.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eoah&AN=35018509&site=ehost-live

Media Attributions

- Figure 4.1: Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological model © Unknown Author is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

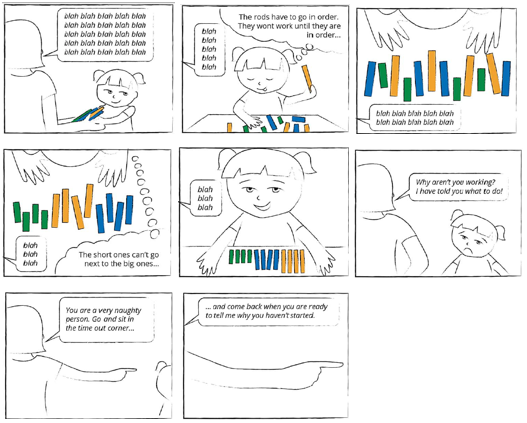

- Figure 4.2: Comic strip of a child. (2019). Australia, USQ. © University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 4.3: Photograph of child with guinea pig. (2018). Australia, USQ Photo Stock. © Photo supplied by USQ Photography is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 4.4 Photograph of a mother and a baby on Unsplash © Kiener, Gabriel. (u.d.) is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Figure 4.5: A photograph of child and cattle, (2018). Australia, USQ Photo Stock. © Photo supplied by University of Southern Queensland Photography is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 4.6: A photograph of a teacher reading, (2018). Australia, USQ Photo Stock. © Photo supplied by University of Southern Queensland Photography is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 4.7: Photograph of a child bouncing. (2018). Australia, USQ Photo Stock. © Photo supplied by University of Southern Queensland Photography is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 4.8: Photograph of a staff member and a parent and child. (2018). Australia, USQ Photo Stock. © Photo supplied by University of Southern Queensland Photography is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 4.9: Photograph of child with spiral book. (2018). Australia, USQ Photo Stock. © Photo supplied by USQ Photography is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license