8 Integral futures: Theory, vision, practice (2020)

This paper was originally published as: Slaughter, R., & Hines, A. (2020). Introduction. In The knowledge base of futures studies 2020 (pp. 1-15). Foresight International, https://foresightinternational.com.au/?product=the-knowledge-base-of-futures-studies-2020

Copyright resides with the author, and it has been licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No-Derivatives 4.0 International licence.

Introduction

This paper provides an overview of Integral Futures (IF) and outlines aspects of its evolution over the last twenty or so years. In so doing it also outlines some of the various uses and applications that have evolved over this time. At the outset it’s helpful to note that the way people respond to Integral Futures—or more correctly integrally informed approaches to futures—depends very much upon where they’re coming from. That is, what they value, what they perceive, and how they create and manage their own unique interior worlds. Most people get the point of the generic four-quadrant model and readily add it to their existing toolkit. Many also find the developmental perspectives within each quadrant illuminating. A closer and more sustained engagement can also reveal an underlying spirit of generousity embedded within the inclusive character of these four “windows on reality.” This is due to the fact that, unlike methods that foreground individual capability and insight, the four quadrants honour and integrate the efforts of many workers and scholars from different cultures and traditions, most of whom would otherwise be overlooked.

It should not be overlooked, however, that Integral Futures can pose real challenges to conventional practice and ways of operating. As is now more widely recognised the main focus of much conventional work is on exteriors—cities, infrastructures, and new technologies—especially new technologies. As noted throughout this book, we frequently encounter either implicit or explicit views with an underlying belief that the future is largely created by and through different forms of technology. Unfortunately, however, such views cannot but radically incomplete and ineffectual because they overlook the interiors that, in a broader view, encompass “half of reality.” As we now appreciate, technology-led views foreground science, technology, infrastructures, and the like but convey thin and unhelpful views of the very people, cultures, and societies from which these objects (and obsessions) spring. Such assumptions and their associated distortions are, for example, clearly central to the default worldview of Silicon Valley. As such they help to explain some of its dysfunctional consequences (see below). This web of barely-glimpsed assumptions obscures the fact that everything around us is socially constructed. No “thing” ever made by human beings stands by itself. It arises from a long period of gestation and development that may reach back centuries.

We can now assert with confidence that each and every technology has as much to do with cultures, worldviews, and values as it does with, for example, mining, metallurgy, and information technology (IT). Thus one immediate consequence of applying integrally informed approaches to Futures Studies & Applied Foresight (FSAP) is that they help to reveal, and then counter, reductionism and embedded structural bias. Another is that they enrich and enlarge the conceptual and operational spaces available. Put simply, this means that deeper, more granular and dynamic views of reality can emerge. The latter become shared resources that impact futures work at every level from organisational strategy to the analysis of global issues.

Evolution of futures methods

Futures methods have changed significantly over recent decades. To put this very briefly indeed, it can be suggested that during the second half of the twentieth century FSAP progressed from an early focus on forecasting and scenarios through a social construction period, followed by multicultural and Integrally informed developments. During the 1960s and ’70s forecasting was regarded as a cutting-edge methodology. Over time, however, it became associated with more mundane uses, just as the rise of scenario building and scenario planning were becoming prominent. These were real additions to the futures toolkit as they permitted the exploration of divergence within forward views. But both forecasting and, to a lesser extent, scenarios tended to focus predominantly on the external world. Critical Futures Studies (CFS), on the other hand, explored approaches that opened up and explored what are now often referred to as the social interiors. That is, they saw the familiar exterior forms of society (populations, technologies, infrastructure, and so on) as grounded in, and dependent upon, powerful social factors such as worldviews, paradigms, and values (Slaughter, 2004).

While futurists had by no means overlooked these social factors, many saw them as insubstantial and problematic. Methods to incorporate them systematically into futures enquiry and action were needed. Perhaps the central claim of CFS was that it is to no small extent within these shared symbolic foundations that certain vital wellsprings of the present, as well as the seeds of many possible alternative futures, can be uncovered and seen more clearly. It’s here that questions of power, social interests, and legitimation became valid subjects of forward-looking enquiry. Since the notion of “alternatives” was long seen as a key guiding concept in futures work generally, locating their origins deep within the ways that different societies actually worked was a significant step forward. Yet inevitably, perhaps, critical futures work itself lacked something essential: deeper insight into the nature and dynamics of individual agency. By finally addressing this missing dimension Integral Futures arguably completed a long process of disciplinary development and initiated a new phase of innovation and change (Collins & Hines, 2010).

Aspects of Integral methods

The three aspects of Integral methodology that are evoked throughout this book are again provided here as Table 1: the four quadrants, levels of worldview complexity, and value levels. We’ve seen above how their careful and discriminating use arguably brings clarity to our “fractured” present and to identifying priority tasks for the future.

| Table 1. Summary of quadrants, worldviews, and values | ||

|---|---|---|

| The four quadrants (or “windows” on reality) | 1. | The lower right quadrant (the exterior world and physical universe) |

| 2. | The upper left quadrant (the interior “world” of human identity and self-reference) | |

| 3. | The lower left quadrant (the interior “world” of cultural identity and knowledge) | |

| 4. | The upper right quadrant (the exterior “world” of individual existence and behavior) | |

| Four levels of worldview complexity | 1. | Pre-conventional (survival and self-protection) |

| 2. | Conventional (socialised, passive, adherence to status quo) | |

| 3. | Post-conventional (reflexive, open to complexity and change) | |

| 4. | Integral (holistic, systemic, values all contributions, works across boundaries, disciplines, and cultures) | |

| Six value levels | 1. | Red (egocentric and exploitative) |

| 2. | Amber (absolutist and authoritarian) | |

| 3. | Orange (multiplistic and strategic) | |

| 4. | Green (relativistic and consensual) | |

| 5. | Teal (systemic and integral) | |

| 6. | Turquoise (holistic and ecological) | |

The four quadrants are, as noted, best understood as providing four “windows” on reality: the Upper Left (UL or individual interior), the Upper Right (UR or individual exterior); the Lower Left (LL or collective interior) and the Lower Right (LR or collective exterior). Within the upper left these intersect with over 20 “developmental lines” and stages of development. Two of the most significant lines are worldview complexity and values. Each quadrant records the process of evolution in its domain—from simple stages to more complex ones. Hence there are four parallel processes, each intimately linked with the others: interior–individual development; exterior–individual development; interior–social development, and exterior–social development. According to Wilber, “the upper half of the diagram represents individual realities; the lower half, social or communal realities. The right half represents exterior forms—what things look like from the outside; and the left hand represents interior forms—what things look like from within” (Wilber, 1995, p. 121).

The four quadrant model can be further elaborated but even simple versions help us to question the widespread habit of viewing the world as if it were a singular monolithic entity—which is how it appears to human senses. We unconsciously run quite different domains together—which unfortunately creates endless confusion. With these clarifications, however, it is easier to see how different principles and tests of truth (etc.) apply within different domains. This, in turn, brings greater clarity to the kinds of tasks that futurists undertake, as well as opening out more innovative solutions (as explored further below).

Levels of worldview complexity

As Table 1 suggests a pre-conventional worldview is one in which individuals are restricted to basic needs such as survival and self-protection. As such human beings operate unreflectively and contribute little to broader social ends. The conventional stage indicates successful integration into an existing social order. Individuals can certainly fit in, so to speak, but they are seldom innovative, except by accident. It is at the post-conventional stage of worldview development that interesting things begin to happen because it is here, in this greatly expanded domain, that innovative thinking and actions occur. Finally, in this brief summary, an Integral worldview values inputs from a huge variety of sources, works fluidly across boundaries and can therefore be innovative in new and original ways. Translating this into FSAP, conventional work clearly has its place, even though it is basically a matter of following rules and precedents. It operates within pre-defined boundaries according to clearly defined rules using well-known ideas and methods. A great deal of futures work in the world is like this. It serves well-known needs and clients. It operates in familiar territory: corporations, planning departments, consultancies, government agencies, and the like. Those working in this mode are likely to have a degree together with long experience in well-known futures methods such as Delphi, trend analysis, and scenarios. By definition they also tend to focus on the exterior collective domain (technology, the infrastructure, the physical world). Such work can now be enhanced by considering post-conventional approaches and explicitly including the interior domains.

On the other hand, post-conventional work recognises that the entire external world is constantly held together by interior structures of meaning and value, some of them very ancient. Two brief examples are the dogged pursuit of economic growth and viewing nature merely as a set of resources for human use. In a post-conventional view, objective accounts of the world are not possible (even within the so-called hard sciences). Rather, human activities everywhere are supported by subtle but powerful networks of value, meaning, and purpose that are socially created and often maintained over long periods of time. Post-conventional work draws on these more intangible domains and certainly demands more of practitioners. It means, for example, that a focus on various ways of knowing (e.g. empirical, psychological, critical) becomes unavoidable. Yet the effort involved is certainly worthwhile. Careful and appropriate use of these methods means that practitioners can gain deeper knowledge and more profound insight into both the currently changing social order and its possible futures. Clearly, Integrally informed futures work can augment these nascent capabilities and apply them in new and truly innovative ways.

Six value levels

A further step took place with the development of spiral dynamics, based on the work of Clare Graves (Beck & Cowan, 1996). Spiral dynamics depicts a nested series of human operating systems that provide many clues as to what is going on under the surface. Again, the path here is from quite restricted and self-regarding modes of being towards more positive, outward, and hopefully more effective ones. The approach can be used as a guide to individual and social interiors but it is not immune to critique and is by no means the only option. As mentioned above, the “values line” in the UL quadrant is only one of over twenty distinct “lines of development” in human beings (others include interpersonal, communicative, self-concept etc.). A practical consequence is that the careful use of such hitherto invisible distinctions means that we can gain greater clarity about our own ways of knowing, our preferences, strengths, blind spots etc., as well as those of others (Slaughter, 1999). What emerges is, in effect, a richer view of human agency.

Such developments imply that successful practice (whatever that means to different people in different places) involves rather more than mastering some of the better-known FS techniques. One of the most striking discoveries is that it is levels of development within the practitioner that, more than anything else, determine how well (or badly) any particular methodology will be used or any practical task will be performed. In one sense this is obvious. An inexperienced or poorly trained practitioner will always get inferior results when compared with others who have in-depth personal and professional knowledge. Yet, especially in past decades, there have been all-too-few professional training programs that have taken seriously the interior development issues of practitioners.

It’s now obvious why the earlier tendency to focus on a practitioner’s cognitive development and methodological skills provided an incomplete picture. As Peter Hayward and others have demonstrated, to be a success in any field demands a good deal more than cognitive ability and technical competence (Hayward, 2003). We now know, for example, that ethical, communicative, and interpersonal lines of development are equally vital to the well rounded practitioner.

Evolution of Integral Futures theory and practice

In their valuable overview of the first ten years of IF Collins and Hines recognise three distinct phases as below and in Table 2:

- The perspective phase: Focus on the theory and initial applications

- The methods phase: Attempts to apply Integral Theory to futures practice in the form of methods

- The sense-making phase: Debate and some controversy

| Table 2. Timeline of Integral Futures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Year | Author | Publication | Contribution to Futures |

| Perspective Phase | 1998 | Richard Slaughter | Transcending Flatland | Foundational Theory |

| 2001 | Joseph Voros | Reframing environmental scanning: An Integral Approach | Refreshes environmental scanning | |

| 2003 | Andy Hines | Applying Integral Futures to environmental scanning | 4-step Integral Scanning Framework | |

| 2004 | Richard Slaughter | Futures beyond dystopia | Questions for applying the Integral Perspective | |

| Methods Phase | 2005 | Mark Edwards | The Integral Holon: A Holonomic approach to organizational change and transformation | Organizational development |

| 2005 | Mark Edwards and Ron Cacioppe | Seeking the Holy Grail of organizational development: A synthesis of Integral Theory, Spiral Dynamics, corporate transformation and Action Inquiry | Organizational development | |

| 2005 | Landrum and Gardner | Using Integral Theory to effect strategic change | Strategic change | |

| 2005 | Peter Hayward | Resolving the moral impediments to Foresight Action | Individual development and ethics | |

| 2008 | Mark Edwards | Every today was a tomorrow: An Integral Method for indexing the social mediation of Preferred Futures | Framework for global social development | |

| 2008 | Chris Stewart | Integral scenarios: Reframing theory, building from practice | Deeper and richer scenarios | |

| 2008 | Peter Hayward | Pathways to integral perspectives | Awakening individual capacities through development | |

| 2008 | Joseph Voros | Integral Futures: An approach to Futures Inquiry | Development of paradigms for inquiry | |

| 2008 | Josh Floyd | Towards an integral renewal of Systems Methodology for Futures Studies | Integral Futures in systems | |

| 2008 | Chris Riedy | An integral extension of Causal Layered Analysis | Assessing Futures tools | |

| 2008 | Richard Slaughter | Integral Futures methodologies | How Integral can be used to enhance Futures | |

| Sense-Making Phase | 2008 | Josh Floyd, Alex Burns and Jose Ramos | A challenging conversation on Integral Futures: Embodied foresight & trialogues | Individual practitioner development |

| 2010 | Various | Various “Response” Special Issue, Futures (42) 2010 | Response to Integral Futures “Special Issue” | |

| 2010 | Sohail Inayatullah | Epistemological pluralism in Futures Studies: The CLA–Integral debates | Response to Chris Riedy critique | |

Following this period IF has been widely recognised as a useful innovation and, as such, has diffused steadily into various forms of practice. That is not to say, however, that it has become universally popular. An international survey carried out in 2009 showed that systemic, linear, and critical methods remained dominant (Slaughter, 2009). Which is perhaps what would be expected given (a) the continued dominance of conventional methods, especially in business and government and (b) the fact that locations where IF can be explored by emerging practitioners remain uncommon. At the same time the significance of Integral Futures theories and practices continues to emerge as the latter are applied to an expanding range of issues and concerns. Here are some examples.

Linking foresight and sustainablity: An integral approach (2010)

A paper by Floyd and Zubevich explores the notion of Integral Sustainability (IS). Central to it is a shift of thinking about sustainability itself. That is, instead of considering a world of objects, and systems of objects, IS considers it in terms of perspectives. As such it represents a deliberate shift from constituting issues as if they were right hand quadrant (RHQ) entities to seeing them as also expressive of left hand quadrant (LHQ) ones. Such a shift immediately evokes the interior worlds of people and cultures and allows the authors to examine how, for example, different worldviews and values help to determine our views of reality. Casting a critical eye over dominant perspectives it becomes clear that external (empirical) ones are, as they put it, “well catered for” in this context. Equally, however, they also find that “there is a deficit in our individual and collective ability ... to take responsibility...” (2010, p. 64). Taking the example of nuclear power as a “solution” to expected energy shortages they identify five distinctive perspectives:

- Energy for all

- Safety first

- Our only hope

- Yesterday’s solution

- Time will tell (Floyd & Zubevich, 2010).

The authors point out that it is not necessary to give each perspective what might be called an equal voice so much as to allow them to be inhabited in ways that are balanced and unbiased. They conclude with an example from Tim Flannery (a well-known Australian scientist and commentator on environmental matters) in which he distinguishes purely utilitarian issues from those that are political and value-laden. They see this as a worthwhile attempt at “perspective formation” that remains open to the real complexities raised when nuclear power is seen as a viable solution through largely empirical eyes. Clearly, from an IS view, it is connected to many other phenomena that also need to be brought into awareness and considered more fully. This expanded picture allows for, indeed enourages, divergence and variety which in turn means that social and value-based solutions can also be brought into play.

Surfacing the intangible (2016)

Great, potentially world-shaping notions are all very well but, at the same time, IF must be able to demonstrate a certain amplitude—that is, be applicable and useful at a range of scales. If it failed to resonate with individual practictioners and were incapable of being used in standard organisational settings then its own future would be in doubt. There is, however, good evidence that, when put to the test of industry consulting and the development of effective organisational strategies, IF performs well in the hands of those who know how to use it. An example (also included in the KBFS 2020 update) is Conway’s account of how she became dissatisfied with standard approches to strategy mainly because, in her words “doing strategy ignores the human factor” (Conway, 2016, p. 232). For Conway “it matters very little how perfect your strategic planning process is or how good your strategy looks on paper, if people aren’t at the core of the process. For me strategy without people is a strategy without a future” (p. 232). She then adds the following:

It is, however, ... time to get strategy out of the box, and move this work from the pragmatic to the progressive futures space. That involves making visible in my work how I re-frame strategy development using the integral four quadrants. It involves challenging the formulaic strategic planning approach that we now might tweak and change, while continuing to use without questioning its underpinning assumptions. It means valuing people and culture as much as process. It also means surfacing a diversity of views about the future to create possible futures. In so doing we value what’s possible as much as data and forecasts and the single ‘right’ future. Most importantly, it’s time to integrate the thinking and doing of strategy to perhaps create a space first where we gather to think strategy, to feel it, to think about possibilities, to acknowledge our emotional responses to those possibilities, and to work collectively across the organisation to identify what needs to happen next. This is a space where our thinking is first expansive and divergent. (Conway, 2016, p. 235)

This is not to suggest that earlier practices in the FSAP domain ignored the inner capacities of human beings. The attention paid to assumptions, for example, in scenario planning is proof of that. Yet it arguably needed the development of IF to provide a more systematic and comprehensive “map” of reality, with distinct reality domains and valuable accounts (plural) of lines of development within all human beings. For this practitioner, as with others, “the integral frame scaffolds the thinking activity in the left-hand quadrants and the doing box in the right-hand quadrants, integrating people and process in strategy development”. She adds, “both are essential. This integrated space connecting thinking and doing is where I now position my work...” (Conway, 2016, p. 235)

The Polak Game (2017)

As time passes, it’s likely that addressing the interior worlds of individuals and cultures will continue to inspire the emergence of new methods and approaches. A further example is a workshop activity initially developed in 2004 at Swinburne’s Australian Foresight Institute by Peter Hayward and Joseph Voros. It draws primarily on two pairs of concepts from Fred Polak’s classic work on images of the future. These are "Essence Optimism" vs. "Essence Pessimism" and "Influence Optimism" vs. "Influence Pessimism". The “Essence” categories refer to a kind of fatalism about whether a particular course of events is changeable or not. The “Influence” ones are used to determine how people feel about the possibilities of human intervention. Both deal with individual interior responses to exterior reality. Stated thus, they sound abstract but when a group of people actually inhabit those spaces in a workshop setting it rapidly becomes clear that, as Hayward and Candy (2017, p. 6) note, much “depends on where you are standing.”

In the original model of the Polak Game people are encouraged to arrange themselves on a 4x4 matrix, first along one linear dimension and then in relation to both. Participants are then encouraged to move around the matrix, to try out different orientations and perhaps settle on a location that best reflects their own provisional views. With careful facilitation they can then be assisted to reflect on the assumptions underlying their choices. The workshop format provides a user-friendly structure for facilitating far-reaching conversations among students and / or clients. It runs for up to an hour or so and provides an accessible approach to exploring such images as properties of individuals and cultures. Stuart Candy, among others, has taken up and adapted this model in other settings and the results of these collaborations have been written up in a short accessible paper (Hayward & Candy, 2017).

Re-assessing the IT revolution (2018-2024)

A further example of IF work addresses the way that the IT revolution has not only failed to live up to the expectations of the early pioneers but also taken a number of regressive and ill-advised turns towards what Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism” (Zuboff, 2019). Moreover, China, a state with no tradition of human rights or interest in democratic norms, is in the process of creating the world’s first IT dystopia. The potential of IT for productive use and social well-being is clearly under real and deepening threat. Yet it’s consistent with the above to suggest that the search for solutions cannot, by definition, be confined to the underlying technology per se. The technology is, of course, a set of consequences of other forces—human, social, economic, and so on—that have been operating over some two decades. So the “way in,” so to speak, only marginally concerns the invention or adaptation of devices. Of far greater significance are questions about social values and worldviews, the very things that were previously missing from FSAP but where so many core issues are grounded. (Slaughter, 2019) Figure 1 illustrates some of these concerns and indicates some of the actions and policy changes suggested within each of the quadrants. Each of them suggests “proto-solutions” or starting points for further and more detailed work.

| Fig. 1. Humanising and democratising IT | |

|---|---|

| Interior human development | Exterior actions |

| Relate human development factors to organizational development and innovation. Implications of different worldviews, values, and choices. Revalue human agency as source of power and capability. Redress their takeover by tech substitutes. Refocus attention on human and social priorities for positive futures. | Abandon the century-long fiction that consumerism equals happiness. Revalue human capabilities. Restrict “screen time” in favor of real-world interaction and experiences. Refine uses of “digital reality.” Protect children and young people from online exploitation. Subject Internet oligarchs to stringent regulations. |

| Interior cultural development | Global system, infrastructure |

| Revalue the sociocultural domain and recognize how IT conditioned these foundations. Develop understanding of how cognitive, social, and economic interests intersect with technical and practical outcomes. Identify role of public goods and moral universals in pursuit of healthy social forms. Abandon business models based on theft of private data. Support progressive innovations such as social democracy and platform cooperatives. | Revise, update civil infrastructure to shift core functions from private interest. Invest powerful new oversight and foresight functions. Subject new digital tech (algorithms, cryptocurrencies, facial recognition) to stringent auditing. Require that innovation and tech development contribute to human, social, and environmental well-being. Ensure that ‘sharing cities’ reflect democratic principles. Steady-state economics. |

Imaging, empowerment and action

It’s not hard to imagine futures in which vision logic, the transpersonal realm, and other such higher order realities were never achieved. The dystopian consequences are clearly displayed in books, films, TV, computer games, the Internet and so on. In this context, the continuing emergence of powerful new technologies can only lead to a continuing disaster for one key reason: the “it” world (or upper right and lower right quadrants) contains no principle of self-limitation. If left to itself “it” will further engulf human cultures and the natural world. But if the scene is shifted, if the parameters are changed, strikingly different world outlooks emerge. For example, a world where “average level” consciousness evoked green values and beyond, and a worldview that is world-centric or above, is one in which the options for deep innovation and change multiply. In this alternative world the powers of new technologies would be seen anew. Raw technical power would be reined in because it would be clearly understood that such power, taken alone, was entirely defeating of the wider human project. In other words, the most interesting futures are those in which human and social evolution matches that of scientific and technological development.

Source: R. Slaughter, The Biggest Wake-Up Call in History, p 168.

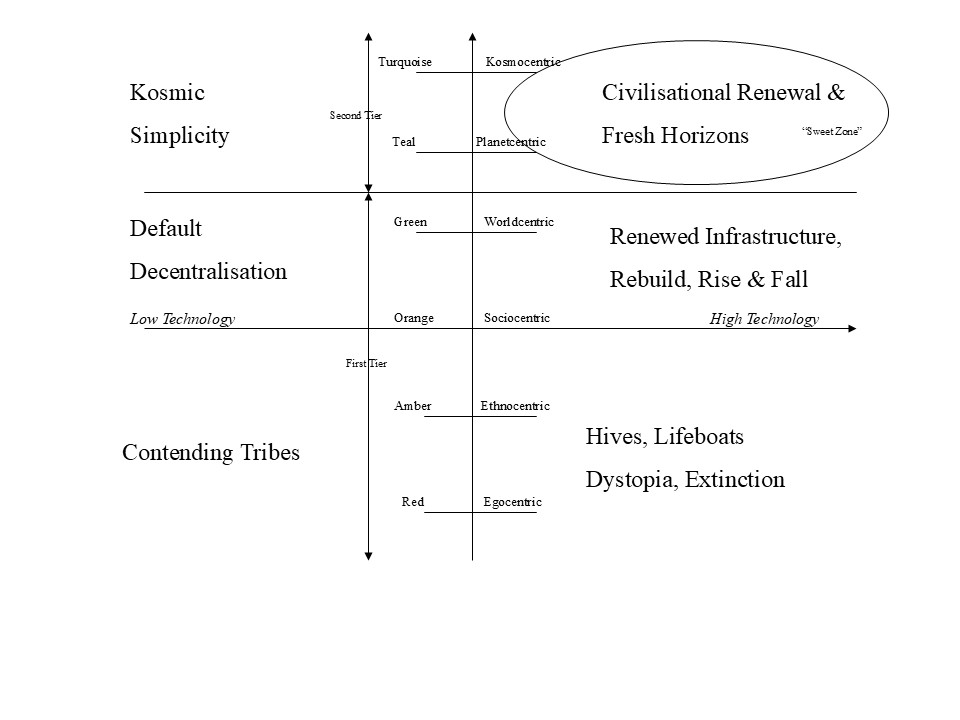

Figure 9 renders some of these suggestions into graphic form, as applied to the medium-term collective future. While not a scenario matrix per se, it follows that general form by running variables against each other to create four cells and six possible futures. These are framed by a vertical line representing the value bands we first encountered in Table 1 above, and one that runs left to right, from low-tech to high-tech. It will be recalled that red, amber, and orange values tend to be exclusive, self-limiting, and often conflict ridden. In low-tech environments they can lead to tribal warfare over land and resources. If we shift towards higher tech versions then the results are larger in scale but with similar outcomes. The key point is that ascending the value hierarchy changes these prospects dramatically. The move from orange to green, and then to teal and turquoise evokes two other scenarios that have been called “green tech” and “earth steward.” Both suggest decentralised societies where human intelligence and progressive values lead to greater resilience and improved prospects for social harmony. These are societies that understand and recognise global limits and also seek to balance out the different contributions of values in relation to many things, including technology (Slaughter, 2010).

The upper reaches of values development then lead into territory that must be treated with care since few people have accessed these advanced levels directly or in a sustained way. Sufficient clues can be gleaned, however, to make some suggestions about how human and social prospects appear to shift into new territory here. That is, they appear to go through a kind of phase change—a shift from one state to another. What have been called “second tier values” are sufficiently broad and deep to recognise the validity and necessity of all other value sets. This gives them unprecedented freedom in that they can inhabit all other value sets without identifying with them, without, that is, seeing the world only from a particular stance. In a profound sense, therefore, people with second tier values are, in essence, peacemakers and protectors of the entire Earth community. They are also proven sources of wisdom and deep understanding. It is, however, the high-tech version of second tier that is the most interesting because it is here that I think we can glimpse the beginnings of thoroughgoing civilisational renewal and the emergence of truly “fresh horizons.”

It should be clear why this domain has been called the sweet zone. It indicates a state of being in which human beings have transcended earlier conflicts and healed the rift between society and nature that was created during the scientific revolution. This is not some dull Utopia but a world characterised by dynamic balance. It has a steady state economy that respects ecological laws and reconnects the threads of mutual interdependence. Clearly such a vision may still lie far in the future. Yet, understood as a compelling image of a truly desirable future, it can act as a powerful magnet that draws people and societies towards its realisation. It follows that the “push” factor of the global emergency, coupled with the “pull” factor of further human development towards such compelling futures, constitute two powerfully productive forces that can be fully acknowledged and more widely employed. The seeds of such a renewed civilisation are not hard to identify but are, perhaps, merely waiting for their chance to grow and develop. The prospect of wise cultures living more lightly upon the earth, supporting the full variety of homo sapiens and its fellow creatures in a mutual web of respect and security, while at the same time employing highly advanced technical means to do so, need not remain distant and unreachable. It can be brought within reach of our collective vision, imagination, and purpose.

Integral futures in practice

With the possible exception of the reference to Conway’s experience above, those who are working in conventional organisational settings could be forgiven for wondering if IF is essentially focused on visions and grand world-shaping ideas. But there is, in fact, plentiful evidence that this is not the case. One way to demonstrate this is to review some back issues of the Journal of Integral Theory and Practice. While it contains its fair share of theoretical work it also contains a wealth of examples of how Integral thinking and methods have been widely applied within many fields and professions. Another way, and one more directly related to IF, is to turn the clock back some 20 years and consider an article on environmental scanning (ES). It took a critical look at conventional business organisations by noting their pragmatism, their inability to grasp the bigger picture, and the fact that they were mostly interested in technical and narrowly financial (rather than human or cultural) goals. Three reasons were put forward to suggest why ES in such organisations fell short of what was needed:

- The typical scanning frame overlooks phenomena that do not respond to empirical “ways of knowing.”

- All organisations are located in a wider milieu—a world that is experiencing stress, disruption, and upheaval on an unprecedented scale.

- Organisations themselves need access to richer, deeper outlooks and more thoughtful, innovative strategies (Slaughter, 1999, p 442-443).

The paper went on to outline a new frame for ES based on the four quadrants of Integral enquiry and briefly outlined what might be involved in referring explictly to what it called these “four worlds.” Following a visit to the Australian Foresight Institute in 2003 Andy Hines was among the first to try out this new approach in the exacting context of a large American chemical company. His conclusions were written up in Futures Research Quarterly. Bearing in mind that it was early days in the development of a new perspective, and in relation specifically to IF he concluded that it provided “three key enhancements.” The Integral approach:

- Emphasises the importance of knowing yourself and your filters

- Provides a model for making sense of what’s going on out there

- Guides you to go beyond the norm and access a wide range of resources (Hines, 2003, p. 28).

Then, in relation to these and other aspects of organisational management and strategy formation Hines added:

- Insights coming from the right-hand side can be measured, while those from the left-hand side must be interpreted.

- (IF therefore) re-balances scanning to integate the empirical and the intuitive.

- (It) challenges your and others’ assumptions (and) aids in communicating insights.

- (It) brings a wider and deeper perspective to new business development, strategy-making and decision-making in general (Hines, 2003, p. 30).

Clearly these are not minor shifts. For example the idea that interpretation and measurement should be treated as of equal significance could be seen as almost revolutionary in some settings. Changes of this magnitude clearly take time. So we should not expect IF to achieve universal influence and application in the short term. But in the longer term it is entirely possible since its influence may be seen as non-trivial as much at the hands-on organisational level as it is for understanding and responding to global dilemmas.

So what general guidelines might emerge from this brief overview for emerging and existing practitioners? Some brief suggestions follow:

- Take time to read around the topic and, if possible, get in touch with someone you trust who has found IF useful in their life and work.

- Don’t rush into organisational settings poorly or half-prepared. Start small with minor projects and applications. Don’t be afraid to get it wrong.

- Don’t feel that you have to follow the rules blindly. There are many aspects to IF and many different way of approaching them. You don’t have to master them all.

- Equally, don’t reinvent the wheel. If or when you run into problems don’t imagine that you’re the first one to do so.

- Check in with a reference group if you possibly can. If you can’t find the right post-grad course, lobby for one to be created.

- Above all maintain a spirit of openness and generosity. Remember that “everyone is right (but) all truths are not equal.”

Conclusion

This paper has argued that Integral approaches to futures enquiry and action provide FSAP with richer options than hitherto. They arguably help us to engage in depth both with everyday concerns and with the multiple crises that threaten our world and its nascent futures. In summary, the distinctive features of Integrally informed work include:

- The underlying rigour and depth of an Integral meta-perspective provides a firm, yet evolving foundation for forward-looking thinking and action.

- The focus on credible accounts of human and cultural development means that the interior worlds of people and societies are seen as significant drivers in their own right.

- Integral perspectives provide well-grounded and legitimate means for challenging the dominance of empiricism, technolology, and instrumentalism.

- Hence narratives of dystopian inevitability can be challenged and pathways towards more viable human futures explored in greater depth and detail.

As futurists we can start looking more deeply into ourselves and into our social contexts to find the levers of change - the strategies, the enabling contexts, the pathways to social foresight (Slaughter, 2004). Such work reaches across previously separate realms. It regards exterior developments with the eye of perception that it consciously adopts. It participates in shared social processes and takes careful note of shared objective realities. In other words this is an invitation to move and act in a deeper, richer, and more subtly interconnected world. Post-conventional and Integrally informed futures work is certainly not for the faint-hearted. Yet it suggests a range of constructive responses to a world currently desperate for solutions to the encroaching global emergency (Slaughter, 2012).

This paper appeared in Slaughter, R. & Hines, A. (Eds.) The Knowledge Base of Futures Studies 2020, APF / Foresight International, 2020. For more information and access please go to: https://foresightinternational.com.au/?page_id=16

References

Beck, D. & Cowan, C. (1996). Spiral dynamics. Blackwell

Collins, T. & Hines, A. (2010). The evolution of integral futures: A status update. World Futures Review, 2(3), 5-16.

Conway, M. (2016, October 24). Surfacing the intangible: Integrating the doing and thinking of strategy. In R. Slaughter & A. Hines (Eds.), The knowledge base of Futures studies (pp. 231-236). Association of Professional Futurists, https://reevolution.espoch.edu.ec/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/1.pdf

Floyd, J., & Zubevich, K. (2010). Linking foresight and sustainability: An integral approach. Futures, 42, 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2009.08.001

Gidley, J. (2017). The future: A very short introduction. OUP.

Hayward, P. (2003). Resolving the moral impediments to foresight action. Foresight, 5(1), 4-10. https://doi-org.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/10.1108/14636680310698216

Hayward, P., & Candy, S. (2017). The Polak game, or: Where do you stand? Journal of Futures Studies, 22(2), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.6531/JFS.2017.22(2).A5

Hines, A. (2003). Applying integral futures to environmental scanning. Futures Research Quarterly, 19(4), 49-62. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/14636680310494735/full/pdf

Slaughter, R. (1999). A new framework for environmental scanning. Foresight, 1(5), 441-451. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636689910802331

Slaughter, R. (2004). Changing methods and approaches in Futures Studies. In, R. Slaughter, Futures beyond dystopia: Creating social foresight, RoutledgeFalmer. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203465158

Slaughter, R. (2004). Futures beyond dystopia: Creating social foresight. RoutledgeFalmer

Slaughter, R. (2009). The state of play in the futures field: A metascanning overview. Foresight, 11(5), 6-20

Slaughter, R. (2010). The biggest wake-up call in history. Foresight International

Slaughter, R. (2012). To see with fresh eyes: Integral futures and the global emergency. Foresight International

Slaughter, R. (2012, April 27-31). Overview for Human Futures [Paper presentation]. World Futures Studies Federation. https://foresightinternational.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/TSWFE_A_Journey_Final2.pdf

Slaughter, R. (2018). The IT revolution re-assessed part three: Framing solutions. Futures, 100(6), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.02.005

Wilber, K. (1995). Sex, ecology, spirituality: The spirit of evolution. Shambala

Wilber, K. (2000). A theory of everything. Shambala

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism. Profile Books