3 Evaluating ‘overshoot and collapse’ futures (2010)

This chapter was originally published as: Slaughter, R. A. (2010). Evaluating “Overshoot and Collapse” Futures. World Futures Review, 2(4), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/194675671000200403

Copyright is retained by the author, and use in this book complies with the Sage RightsLink page, and uses the accepted manuscript version, ‘in a book authored or edited by you, at any time after the Contribution’s publication in the journal’. In accordance with this reuse, a full reference (including live-linked DOI) is included for the chapter.

This chapter is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No-Derivatives 4.0 International licence.

Introduction

You don’t have to be a professional futurist / foresight practitioner to realise that premonitions of disaster have a long history. Moreover, events such as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and its continuing aftermath to remind us that the world is currently nowhere near what might be called an equilibrium state. Yet behind the issues reflected in daily headlines (economic woes, political dilemmas, armed conflicts, technological threats, global warming…) there’s a deeper and more systemic danger that receives too little attention. It concerns the way that humanity’s collective impacts have already breached some global limits and look set to exceed others in due course.

The puzzling thing is, however, that this is not some sort of hidden secret. The hazards and risks of unlimited economic growth have been understood and spelled out with increasing clarity and rigour over half a century or more. Yet, these critical signals of change have been widely ignored in favour of business-as-usual thinking, and the continued pursuit of growth at any cost. So long as this continues it’s widely believed that there will be sufficient wealth, in principle, to keep the rich happy and to keep everyone else diverted from the necessity of thorough-going renewal. However, attempts to pacify the poor become less effective over time. They’ve failed in the technically advanced nations and in the least developed as well. Hence, overall, we’re confronted by an upheaval in human affairs on a scale exceeding anything previously witnessed.

The term overshoot and collapse merged from the language of systems analysis and will be unfamiliar to some. Yet the perspective it represents offers new clarity about the role of humankind in its world. This chapter therefore considers one of the most significant pieces of work ever carried out on global issues – the Limits to Growth (LtG) study and its evolution over time. Later work evaluated its relevance to the early 21st Century world and also introduced fresh evidence regarding global change. Two other approaches are also briefly mentioned here. One offers a Gaian perspective on the human predicament. The other is a comparative study that considers how previous societies exceeded their own limits and, in so doing, offers some suggestions for ours. Both add something to the debate, but certain other caveats remain. Overall, the intention is to answer three questions. First, is overshoot and collapse a credible notion based on firm evidence. Second, if so, what does this imply? Finally is overshoot and collapse inevitable? If a measure of clarity emerges from this discussion, we’ll at least have made a start on the unprecedented tasks facing us.

A very particular danger

In many – perhaps most – situations it seems reasonable to adopt a wait and see attitude. Then, if the problem worsens, there is usually time to respond to correct it. Some situations are, however, time critical meaning that to wait is to court disaster. Examples are legion but we appear to have great difficulty knowing when to act and when to wait. This may be due to natural reticence, the complexity of ill-defined situations, opportunity costs and so on. Increasingly, however, we are, to some extent, becoming aware that we’re collectively faced not merely with any particular threat but with a number of them coming together at roughly the same time. Moreover, this is occurring on a global scale. Which means that the encroaching challenges to civilisation cannot be resolved by any single country or jurisdiction. Also, just to make things a little harder, this challenge is not one that stands before everyone, everywhere, as a clear and comprehensive. Rather, it’s one that challenges people, organisations and societies in many different ways.

This particular danger is therefore only visible within prepared and open human minds. It takes on greater reality either due to the experience of change that is often felt only by minorities or those whom we perceive as distant, or through the kind of careful study and extended reflection that, by definition, will only be undertaken by a few. Currently there’s still very little effective institutional capacity for social foresight anywhere. Thus, under present conditions, only a relatively small minority of people can see the danger clearly and therefore become motivated to start working on solutions. Then when the latter appear in embryo, so to speak, they confront a power structure with an array of embedded ways of knowing and doing. Consequently, they face a social and economic system that wants nothing of these ideas unless they can be bent to immediate uses – such as those of power and profit. In the wider picture this is contradictory and a certain recipe for disaster. How, therefore, can the threats to humanity be made clear and credible such that whole societies can begin to consciously respond to them?

It’s not enough to call, as some already have, for the same sort of responses that are elicited by war and the threat of war. The threats to survival in most rich developed countries are seldom that direct or clear. Unlike those living on the edge in various parts of the Third World, such threats on the whole don’t confront still-affluent populations directly in the face with the kind of immediacy that accompanies famine and war. Nor are we yet standing on the brink of extinction with the threat of all that we hold dear being torn apart before our eyes (though, in truth we are closer to it than many realise). For those sufficiently affluent who remain largely insulated from natural processes, the threats remain too subtle, distant and complex to cause them to re-think assumptions and work together in ways that matter. Clearly, we need new rationales for action backed by meaningful evidence and compelling options. A central purpose of The biggest wake-up call in history is to provide part of the groundwork needed to achieve this (Slaughter, 2010).

The limits to growth project

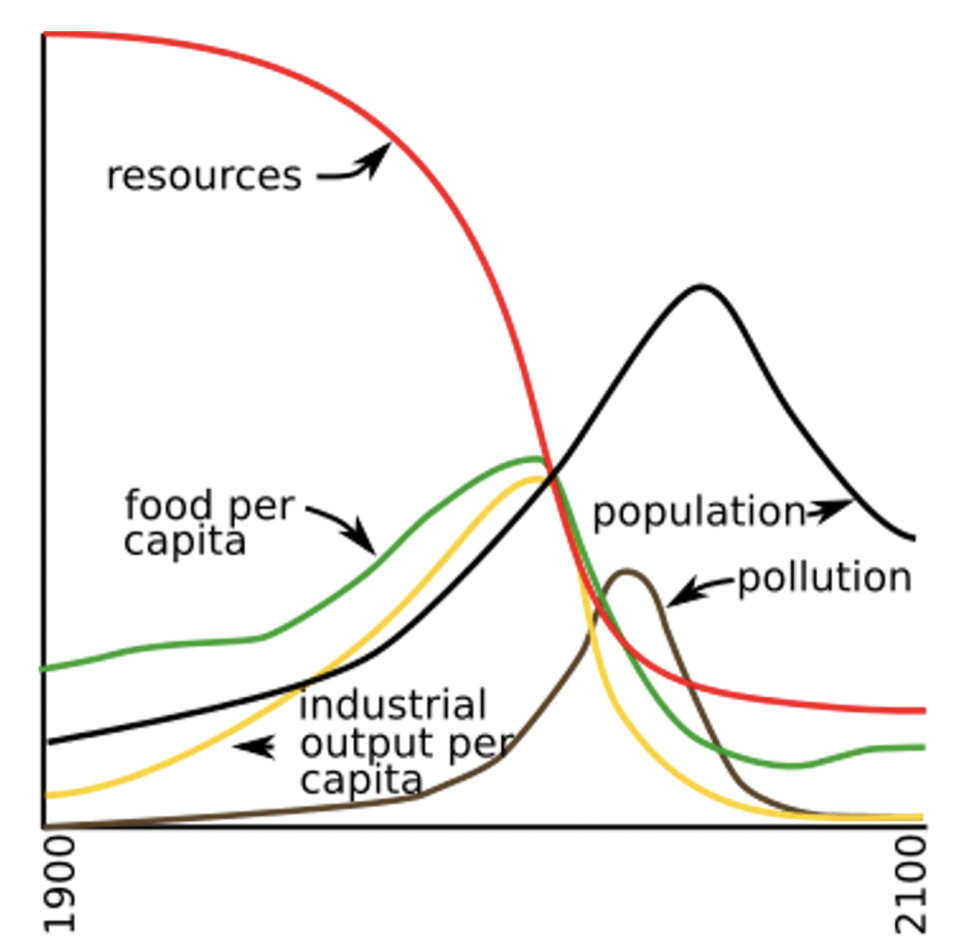

The 1972 publication of The Limits to Growth (LtG) created a debate that has ebbed and flowed ever since (Meadows, et al., 1972). The book looked in some detail at the phenomenon of exponential growth and argued that its dangers had been widely overlooked. It provided a number of examples which suggested that, given such growth it’s possible to move very quickly from a situation of abundance to one of scarcity. This led to a crucial insight that’s constantly overlooked by climate change deniers and others, i.e. that precise numerical assumptions regarding limits are not particularly helpful when set against the inexorable fact of exponential growth. It follows that a combination of population growth, agricultural production, resource depletion, industrial output and pollution could well lead to the collapse of civilisation unless limits to growth are observed before they reach crucial levels. Such conclusions were based on computer modelling techniques that were not widely known or understood at the time. Hence, on one hand they appeared to give the thesis a certain credibility while, on the other, some of the underlying assumptions and methodologies were widely questioned.

Source: Mefisto, K. (2025). Limits to growth, Wikimedia Commons. Attribution at the end of this chapter.

The Club of Rome, which had sponsored the report, also provided sufficient publicity to keep it in the public eye for some time where it attracted much interest and comment. But the central message of the book was uncompromising and it’s worth setting it out in full.

There may be much disagreement with the statement that population and capital growth must stop soon. But virtually no one will argue that material growth on this planet can go on forever. At this point in man’s history, the choice posed above is still available in almost every sphere of human activity. Man can still choose his limits and stop when he pleases by weakening some of the strong pressures that cause capital and population growth, or by instituting counter-pressures, or both. Such counter-pressures will probably not be entirely pleasant. They will certainly involve profound changes in the social and economic structures that have been deeply impressed into human culture by centuries of growth. The alternative is to wait until the price of technology becomes more than society can pay, or until the side effects of technology suppress growth themselves, or until problems arise that have no technical solutions. At any of those points the choice of limits will be gone. Growth will be stopped by pressures that are not of human choosing and that, as the model suggests, may be very much worse than those which society might choose for itself (Meadows, et al., 1972, pp. 153-4).

The authors also argued that placing our faith in technology as the ultimate solution diverts our attention from what they called the ‘ultimate problem’ – dealing with growth within a finite system. In setting out this thesis so clearly and directly the LtG study, in effect, fired a couple of shots across the bow of the great ship ‘Progress’ that had been steaming steadily ahead for several centuries. But, far from considering the thesis on its merits, what actually happened is that, after the initial burst of publicity and comment, the study was effectively ignored. This occurred for a couple of reasons. First, the growth imperative is the powering dynamic of the capitalist system. As noted above, continued growth means that the cake can be enlarged such that, in theory, everyone can have more. Given that the purported overshoot was way off in the haze of the future, there was simply no countervailing force available to reign in a process from which so many people had clearly benefited.

Second, in posing the issue this way – through computer modelling, graphs, diagrams and so on – the authors of the study tended to overlook the full personal, social and cultural implications of their proposals for controlling growth and avoiding disaster. The former came across as a challenge to forces that were barely glimpsed from within the study and certainly not named or engaged in any meaningful way. Nevertheless, it is wrong to think of this work as a failure. It was a first step that succeeded in raising issues and articulating concerns about the viability of a growth-oriented and technology-focused culture, that needed to be represented in the public domain.

Another stage in the LtG project was marked with a 1992 work called Beyond the Limits (Meadows, et al., 1992). It presented an updated and clearer account of exponential growth, backed by improved modelling techniques. It also reviewed the nature of limits and reconsidered the dynamics of growth in a finite world. One of the new features of the work is the way it demonstrated beyond all doubt that foresight had become a structural necessity. In a section called ‘Why overshoot and collapse?’ the authors wrote that:

Overshoot comes from delays in feedback – from the fact that decision makers in the system do not get, or believe, or act upon information that limits have been exceeded until long after they have been exceeded…The larger the accumulated stocks, the higher and longer the overshoot can be. If a society takes its signals from the simple availability of stocks, rather than from their size, quality, diversity, health and rates of replenishment, it will overshoot (Meadows, et al., 1992, p.137).

There then follows a statement that not only illuminates the situation we’ve now reached but also suggests part of a solution.

Physical momentum causes delay not in the warning signals, but in the response to the signals. Because of the time it takes forests to grow, populations to age, pollutants to work their way through the ecosystem, polluted waters to clear, capital plants to depreciate, and people to be educated or retrained, the economic system can’t change overnight, even if it gets and acknowledges clear and timely signals that it should do so. To steer correctly, a system with inherent physical momentum needs to be looking decades ahead’ [Emphasis added] (Meadows, et al., 1992, p.137) .

There may be no clearer explanation as to why social foresight has become a structural necessity. Without it, or something very similar, crucial signals from the environment are not received, not understood nor interpreted correctly and certainly not fed into critical decision-making processes across the board. Such oversights have already become prohibitively expensive not merely to people and the human economy but also within the progressively degraded global commons upon which all life depends.

Later in the book the authors explain why timely action is so central to their thesis. Growth can be insidious because it may shorten the time available for key decisions to be made. Systems that had coped during slower periods of change may be close to reaching their limits and in danger of collapse before awareness of the fact had been achieved. Technology and markets that worked well during slower periods of change could be overwhelmed as a society rapidly reached interconnected limits. One reason for this is the cost of adjustment mechanisms – such as new tax regimes or more energy efficient technologies. Another is that distortions and delays occur in feedback (information) loops. For example, scientists may fail to be heard and national councils may be politically neutralised, undermined or unresponsive. Finally, and crucially they note that:

The market and technology are merely tools that serve the goals, the ethics and the time perspectives of the society as a whole. If the goals are growth-oriented, the ethics are unjust, and the time horizons are short, technology and markets can hasten a collapse instead of preventing it (Meadows, et al., 1992, p.180).

The recognition that intangibles such as goals, ethics and time perspectives was of primary significance. In this and other ways Beyond the limits offered a new understanding informed by over 20 years’ work, critique and reflection. Apart from describing the dynamics of exponential growth more clearly, and with up-to-date examples, the analysis was beginning to focus on the human and social sources of the issues they raised. Indeed, near the end of the book the authors concluded that present generations were faced with two enormous tasks. One was to learn to operate within the earth’s limits, the other to thoroughly revise the relationship between its inner and outer worlds (Meadows, et al., 1992, p. 216).

This is crucial insight. It alerts us to the fact that for such ideas to take root and emerge in practice requires readiness and capacity. In turn what this indicates is the adequacy or otherwise of the interior resources available within people and cultures. Beyond the limits concluded by outlining a number of shifts that the authors considered were necessary in culture, human behaviour and governance. Briefly, these included visioning, truth telling and loving – qualities that thus far do not appear to have featured anywhere in public or international affairs (Meadows, et al., 1992, pp.224-236).

A third book in the series was published in 2005 and appropriately called Limits to growth: The 30 year update (Meadows, et al., 2005). It presents what the authors refer to as pervasive and convincing evidence that humankind had by now exceeded the carrying capacity of planet Earth. They also acknowledged that:

The idea that there might be limits to growth is for many people impossible to imagine. Limits are politically unmentionable and economically unthinkable. The culture tends to deny the possibility of limits by placing a profound faith in the powers of technology, the workings of a free market, and the growth of the economy as the solution to all problems, even the problems caused by growth’ (Meadows, et al., 2005, p. 203).

Part of the book is devoted to reviewing criticisms of the earlier works, considering changes in the World3 model, testing assumptions and showing very clearly why they believe humanity is already living in overshoot mode. Though dealing with some very difficult issues, it avoids being either shrill or defensive. The authors are clear about their values and open about their methodology. They intend to open out new possibilities for understanding and dealing with the global predicament. In particular they suggest a number of ways to avoid overshoot and collapse of natural systems. These include:

- Reducing population and capital growth through proactive decision-making rather than the raw feedback emerging from the system itself.

- Reducing the use of energy and materials by using capital more efficiently via de-materialisation, value shifts and related lifestyle innovations.

- Taking heed of the role of ‘sources and sinks’ of energy and raw materials such that they can be protected or restored.

- Improving signals from the environment such that they are seen, heard and responded to in a timely fashion.

- Encouraging society to get used to thinking long-term and, in so doing, ensure that rationales regarding long-term costs and benefits become clearer.

- Taking action to reduce, prevent or reverse land degradation and erosion. (Meadows, et al., 2005, p.178)

Clearly these suggestions build on the earlier work and are stated with as much, if not greater clarity and force. Yet a crucial continuity from previous decades still applies. They still amount to an all-but-impossible program for growth and market-oriented societies as they are presently constituted. There’s still insufficient broad understanding within society as a whole and, as a result, little or no political will to ensure that recommended actions will be taken seriously, let alone rendered into any form of practice. Yet the interesting thing to note is that, in failing to respond adequately to this diagnosis, the issue has not been resolved, merely deferred. We can be quite certain about this because it has steadily re-emerged in the yet more extreme and intractable form of global warming. Recognising this, the authors also consider what they call ‘transitions’ to a more sustainable system. They note that there are three ways that the human world can respond to the signals that environmental limits are being exceeded. These are:

- Deny, disguise or confuse the signals being generated within the global environment;

- Take action to temporarily alleviate growth pressures through temporary ‘solutions’ (such as technological fixes); or

- Seek out and clearly identify the underlying causes so that the structure of the system becomes evident and, in principle, be changed over time. (Meadows, et al., 2005, pp. 235-236)

Since that time there’s little doubt that the dominant response is the first, followed by the second. There’s little or no prospect of even approaching the latter at the present time as changing the structure of the system poses almost insuperable problems. Moreover, it assumes levels of clarity and understanding that almost certainly exceed our individual and collective grasp. The conclusion seems to be that experience will continue to be a more effective teacher than foresight. Yet we should pause before assuming the worst. For one thing, new insights are constantly arising. For another, this is far from the open and shut, gloom and doom story that often provides a spurious reason to do nothing…

Reviewing and evaluating limits to growth

One of the co-authors of the Limits series, Jorgen Randers, took a fresh look at the whole issue in a 2008 paper called ‘Global collapse, fact or fiction?’ (Randers, 2006). He reminded readers that the main point of the LtG research was not stopping growth but, rather, to provide a basis for understanding the dynamic of overshoot and collapse. He affirmed that this could well occur early in the 21st Century if humanity continued to disregard global limits and environmental constraints. If humanity’s ecological footprint exceeded the planet’s carrying capacity there could be…

…a sudden, unwanted, and unstoppable decline’ in the average well-being of many people. Such a collapse could be considered global if it affected ‘at least 1 billion people, who lose at least 50% of something they hold dear, within a period of 20 years’ (Randers, 2006, p. 857). [1]

This is obviously a measure that can be critiqued on a number of grounds, not least that it vastly under-states the magnitude of likely future events. He then went on to provide four of many possible ‘local’ examples of this dynamic that have already occurred: the over-harvesting of wood on Easter Island that led to the collapse of that society; the over-fishing of Canadian cod which destroyed the stock and forced the closure of the fleet; the over-valuation of share prices leading to boom-and-bust cycles and, finally, the global financial crisis of 2008-9. In the light of these examples, he suggests that the overshoot and collapse syndrome is based on two major factors. These are, first, the way that the supposedly well-informed can deny what is happening right up to the point where it occurs and second, the continuation of growth beyond sustainable levels. This, in his view, is the root cause of the problem.

Such local phenomena can also be seen in more global terms by looking more closely at humanity’s total impacts, or its ecological footprint. This later work independently confirms the essence of the LtG thesis and, incidentally, also suggests that humanity may have shifted from a sustainable growth trajectory to an unsustainable one as far back as the 1980s. According to the Global Footprint Network, by 2010 humankind had already pressed into service some 25% more land than was considered available on the planet (Randers, 2008, p. 859). The main reason provided was the huge expansion in forested areas that’d be needed to soak up excess CO2. Without venturing too far into the global climate change issue, it’s sufficient to note that if this background (i.e. the empirical facts, a systems perspective and an appreciation of psychological factors) were more widely appreciated, then current efforts to reign in CO2 emissions would not be such an uphill battle. They’d arguably make sense to more people and the delays in decision-making may well also be reduced. To his credit, Randers gives a number of examples of these delays that are numerous enough to suggest that they’ll not be easily or quickly resolved (Randers, 2008, p. 861). [2]

A further significant contribution to clarifying and resolving these questions is a paper by Graham Turner in which he compared the LtG study with what he terms ‘thirty years of reality’ (Turner, 2008). Since it’s a fairly technical paper this account will focus on three of its key conclusions that address the reception accorded to the LtG project, the reliability of the systems model it used and, finally, how well the standard run scenario compared with subsequent trends in the real world. Turner suggests that a key reason why recommendations from the project were not taken up was that:

From the time of its publication to contemporary times the LtG has provoked many criticisms which falsely claim that the LtG predicted resources would be depleted and the world system would collapse by the end of the 20th Century. Such claims occur across a range of publication and media types, including scientific peer reviewed journals, books, educational material, national newspaper and magazine articles, and websites. (But) this paper shows them to be false’ (Turner, 2008, pp.13-14).

This is relevant because it is here in the reception accorded to the LtG that we can see some of the ways a dominant reality responds to initiatives that challenge it. It’s also reminiscent of the Meadows’ response #1 (deny, delay or confuse the signals) mentioned above. More startlingly, perhaps, Turner’s comparison of the original scenarios with subsequent data also revealed that there was a good correlation between what had been termed the standard run scenario and the real world. He noted that that had there been fundamental flaws in the original work, then scenario outputs he derived from the World3 model would be unlikely to match the long time-series data so closely. For him, the close correlation of scenario outputs with actual historical data not only served to validate the model, it also increased the likelihood that the global system would go on to display the same, or similar, underlying dynamics suggested by what the Meadows team referred to as the standard run scenario (Turner, 2008, p.34). Some details of the latter also closely matched other emerging issues such as those of peak oil and constraints on food production in some areas. Given these similarities Turner concluded that the global system was indeed on an unsustainable trajectory. In the absence of appropriate technical innovation and vastly reduced demand, some sort of global collapse looked likely before mid-century (Turner, 2008, p.37-38).

These are powerful and challenging conclusions, but the truly remarkable thing is that many years later they are still not widely understood or taken seriously. That said, it’s useful to acknowledge that the continuing efforts of scholars and others to explore and apply the implications of the LtG debate have resulted in the creation of real-world innovations and practices with wide applicability (Slaughter, 2022).

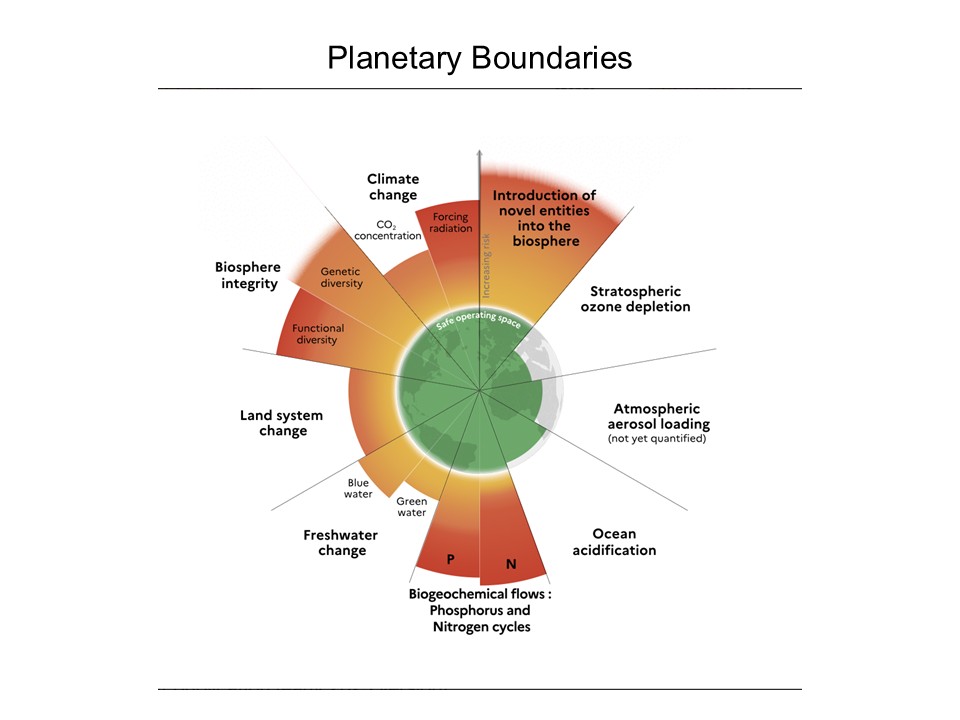

Then in 2009 Johan Rockstrom, director of the Stockholm Environment Institute, Sweden, convened a meeting of specialists to take a fresh look at human impacts on the global system (Rockstrom, 2009). This time the focus was on nine interlinked planetary boundaries and the thresholds associated with each. Figure 2 shows the most recent results, newly updated in 2023. More than a decade earlier the research team had found that planetary boundaries had already been exceeded in three cases (climate change, species extinctions and the nitrogen cycle), that four more were close to being breached (ozone depletion, freshwater usage, ocean acidification and changes in land use), but that there was insufficient data to decide on the remaining two (atmospheric aerosol loading and chemical pollution). These are fairly dramatic results and they should have set the alarm bells ringing. Yet the article ends by stressing the ‘gaps’ in our knowledge and, somewhat perversely, arguing that if key thresholds are not breached, then social and economic development could continue well into the future.

A later New Scientist article reviewed the results of the study and concluded that however the topic was approached, the Earth’s life support systems were in poor shape. Yet it also concluded with the good news that the ozone hole in the atmosphere was slowly recovering, suggesting that successful action was indeed possible. In such cases, a dire situation was minimised in favour false optimism. While it makes sense to avoid overstatement, it seems as though parts of the scientific community have sometimes preferred to sugar the pill, rather than come out and clearly state that humanity is currently set on a no-win path. Others, however, are rather more forthcoming.

Notions of Collapse

As indicated above there’s more to the notion of ‘collapse’ than first appears. Hence, it’s useful here to consider two rather different accounts.

James Lovelock is well known as the originator of the Gaia hypothesis, the notion that the Earth is a self-balancing system in which all the elements of nature work together to maintain global equilibrium. To some it is a metaphor and to others a useful way of thinking about an integrated planetary system. In a number of publications Lovelock drew on a number of empirical sources to propose that humanity is faced with its greatest challenge ever – to restore the balance between it and the Earth or be mercilessly pushed to the margins. In his view global warming (which he called global heating) from rising levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will raise global temperatures by as much as 6 to 8 degrees centigrade and, in the process, trigger abrupt and irreversible climate shifts. Among them are the melting of the polar ice caps, the switching off of the Gulf Stream (or ocean conveyor) that warms Western Europe, abrupt shifts in rainfall patterns and the rendering of large tracts of land unproductive and uninhabitable. Sea levels will rise such that coastal cities and large numbers of people will be displaced. Overall, he anticipates “a climate storm the Earth has not seen for 55 million years” (Lovelock, 2006, p.105).

In this catastrophist view the human species has become complacent about its place upon the earth and takes seriously neither its current impacts nor where these will lead. Lovelock comments that our journey into the future is ‘amazingly unprepared’ (Lovelock, 2006, p. 155). Yet enough is known about the global system, and about how it functions, to provide us with clear warnings of what lies ahead and perhaps time to deal with it. Business-as-usual thinking no longer makes any sense and is seen as evidence of the inertia of the industrial outlook. If it remains in place, then ‘our species may never again enjoy the lush and verdant world we had only a hundred years ago’… and furthermore … ‘few of the teeming billions now living will survive’ (Lovelock, 2006, p.60)

The author added several ideas to the developing debate. First, he asked us to set aside notions of ‘sustainable development’ and so-called ‘renewable’ energy sources. In his view both are little more than romantic dreams. In one of the most outspoken passages, he writes that:

Our religions have not yet given us the rules and the guidance for our relationship with Gaia. The humanist concept of sustainable development and the Christian concept of stewardship are flawed by unconscious hubris. We have neither the knowledge nor the capacity to achieve them. We are no more qualified to be the stewards or developers of the Earth than are goats to be gardeners’ (Lovelock, 2006, p.137)

Second, he argued forcefully for a re-consideration of the possible role of nuclear energy which, in his view, had been too-readily demonised and dismissed but is the only source of energy that, in the absence of fusion power, could provide base-load electricity for the foreseeable future. In this respect he parted company from other observers who broadly identify with the environmental movement who see nuclear power as an expensive diversion.

Third, he proposed a value change at the heart of the relationship between the species and the planet. He asked us to think of Gaia first and humanity second. That is, to reverse the deeply inscribed habits, ways of thinking, operating procedures and the like that have guided human behaviour over millennia. In part this echoes the view from the LtG study which suggests that ‘we have to make our own constraints on growth and we have to do it now’ (Lovelock, 2006, p.142). Yet since the prospects of achieving either of these in the near future remains remote, what should we do? A small ray of hope is offered in the following statement:

We need the people of the world to sense the real and present danger so that they will spontaneously mobilise and unstintingly bring about an orderly and sustainable withdrawal to a world where we try to live in harmony with Gaia’ (Lovelock, 2006, p.150).

There are a number of criticisms of the Gaia hypothesis, one of which is the way it employs the metaphor of a benign Earth Goddess to represent concepts from science in general and systems science in particular. Another later evidence suggested that Gaia herself may not actually be that benign. For example, Peter Ward has argued that subsequent discoveries cast serious doubt on the Gaia hypothesis. He writes:

Two lines of research are particularly damning: one comes from deep time – the study of ancient rocks – and the other from models of the future. Both overturn key Gaian predictions and suggest that life on Earth has repeatedly endured Medean events – drastic drops in biodiversity and abundance – and will do so again in the future’ (Ward, 2009, pp. 28-31).

Indeed, some mass extinctions were indeed driven by ‘microbial’ sources including ‘huge blooms of bacteria belching poisonous hydrogen sulphide gas (Ward, 2009, pp. 30-31.)’. On such occasions, life seems to be ‘pursuing its own demise’ (Ward, 2009, pp. 30-31.) which certainly casts some doubt upon the presumed benevolence of Gaia.

Many responses to such downbeat views are, of course, possible. On the one hand they could reinforce an existentialist viewpoint that life was always pretty meaningless anyway. On the other one could also conclude that, if life was so transient, rising and falling over time, then it could also be considered precious and therefore particularly worthy of our care and respect.

This reveals a vital clue. The future of the world depends not only on the clarity of the diagnosis provided by science. More profoundly it depends on our individual and collective responses that emerge from values, perceptions and worldviews. The perception that the human race itself may well be advanced in closing down the wellsprings of life on the planet, destroying its life-support systems and interfering in the great cycles of matter and energy, arguably projects the species into new territory within which more empowering responses can also be envisaged.

If, instead of labelling potentially disastrous futures as mere ‘gloom and doom,’ we openly acknowledged the reality of what collectively stands before us – an uninhabitable world and the decline of the human species – what then? We might discover sources of insight, strength and motivation that would drive some of these deep-seated and systemic changes in self-concept and in how we live and relate to the rest of the world.

As noted above, most of the evidence for the overshoot and collapse hypothesis comes from using the past to model various possible futures. Complementing this approach is another sub-field of enquiry that looks at how a number of past societies dealt with these issues. One of the most influential is Joseph Tainter’s work on social collapse that turns on the careful rise and fall of social complexity at different times (Tainter, 1988). A further and more accessible, addition to this literature is Jared Diamond’s work Collapse which provides further insights into the factors and dynamics involved (Diamond, 2005).

While Diamond’s earlier work used comparative studies of earlier societies to understand how they were differentially built up and established, Collapse focuses on how they either survived or broke down. Eight factors are held to have been responsible for past breakdowns: deforestation and other habitat destruction; soil erosion, salinisation and loss of fertility; problems with water management, overhunting, overfishing and the effects of introduced species; and finally, contributing to all of these, overpopulation. Four factors are cited that affect our own prospects. These are anthropogenic (human caused) climate change, toxins in our environment, energy shortages and, again, population growth.

The bulk of the book provides a valuable compendium of case studies showing how these factors operated at different times and in different places. Diamond’s hope is that in understanding the past we may be clearer about the causes of collapse and act more decisively to prevent it. Thus, the last three chapters are devoted to the practical lessons that have emerged. He asks, ‘why do some societies make disastrous choices; how does big business relate to the environment; and finally, what does it all mean for us today?’ Among the reasons cited for societal bad choices are the:

- failure to anticipate a problem before it arrived;

- failure to perceive a problem after it has arrived; and,

- failure to solve a problem after it has arrived and been recognised (Diamond, 2005, pp.421-7).

Reasons for these failures have multiple and familiar explanations including: perverse subsidies, inappropriate responses to the tragedy of the commons (i.e. over-exploitation of commonly owned resources) and the over-extension of values or, conversely, adherence to currently disastrous ones. In addition, various psychological factors are mentioned including crowd psychology and the varieties of human denial. Some cogent observations are made here but he passes rather lightly over this territory. In Diamond’s hands, big business is treated with remarkable restraint. He considers positive examples of constructive, long-term thinking and also areas such as agriculture and ocean fisheries where, as we’ve seen, unsustainable practices are common. Yet he rather curiously holds ‘the public’ responsible for actively or passively acceding to business practices.

The final chapter, however, puts aside any residual doubt about where Diamond stands. It summarises a dozen familiar concerns such as the loss of natural habitats and the steady decline in genetic diversity, various environmental insults, water and energy shortages, chemical pollution, climate change and continued growth in the human population. He concludes, as others have, that:

Our world society is presently on a non-sustainable course, and any of our 12 problems of non-sustainability that we have just summarised would suffice to limit our lifestyle within the next several decades. They are like time bombs with fuses of less than 50 years’ (Diamond, 2005, p.498).

This conclusion is strikingly similar to Turner’s, above. In Diamond’s view, the major oversight for which we are all responsible is that ‘the prosperity that the First World enjoys at present is based on spending down the environmental capital in the bank’ (Diamond, 2005, p.509). Thus there’s no longer any room for debate about whether past collapses have modern parallels and associated lessons. Rather, ‘such collapses have actually been happening recently, and others appear to be imminent. Instead, the real question is how many more countries will undergo them (Diamond, 2005, p.517).’ Given all this work, and especially the in-depth examination of a dozen or so case studies, the grounds for hope that Diamond offers seem rather slender. Here is a summary.

- Because we are the cause of our environmental problems, we are the ones in control of them, and we can choose to stop causing them and start solving them.

- We can muster the courage to practice long-term thinking, and to make bold, courageous, anticipatory decisions at a time when problems have become perceptible but before they have reached crisis proportions.

- But do we also have courage to make painful decisions about values…e.g. how much of our traditional consumer values and First World standard of living can we afford to retain?

- We can be grateful that past societies lacked archaeologists and television, whereas today TV documentaries and books show us in graphic detail how past societies collapsed.

- It follows we have the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of distant peoples and past peoples (Diamond, 2005, pp.521-525).

In this view we have the advantages of comparative knowledge, technically advanced media and a range of admirable human qualities. Yet this does not explain our long-standing cultural myopia or why, equipped with these resources, we still appear committed to an ‘overshoot and collapse’ trajectory. To locate such an explanation suggests that we need to look further into ourselves and into the interiors of advanced societies.

The meaning of Overshoot and Collapse

The Limits to Growth study has been critiqued for its technocratic emphasis, its lack of engagement with affected constituencies, its assumptions regarding the efficacy of market mechanisms and its relative lack of attention to the social, economic and political dimensions of issues such as climate change (Easton, et al., 2010). These criticisms are certainly valid but do not materially detract from its overall significance. For one thing the LtG study was, in itself, a wake-up call, an invitation to a wider debate and to a more adequate view of humanity and its place in the world. For another, it did, in fact, anticipate two of the greatest challenges of our time – climate change (caused by CO2 overwhelming natural ‘sinks’) and resource depletion (of which ‘peak oil’ is the prime example). Both were sanctioned by a careless profiteering mentality that remained ignorant of global limits and sponsored forms of development that led directly to the current impasse.

The main conclusion to be drawn from these accounts is that humanity is indeed living a long way beyond its means and has been doing so for a while. The cultural triumphalism often expressed by the currently powerful looks both foolish and empty when viewed in this light. The human species is consuming natural capital at a frightening rate rather than living on the renewable interest. Wherever we care to look the evidence is clear. In general terms the presence of over 8 billion people is degrading the Earth and reducing its capacity to support life. But this is not merely a question of raw numbers. Different populations clearly exert different impacts and the currently affluent are quite clearly consuming more of their earth share than is just or wise (Kemph, 2008).

For some time, the IPAT formula has been used to give an approximation of the different impacts associated with people of different living standards. Impact was held to be a multiplier of Population x Affluence x Technology. In 2009 George Monbiot suggested that a more accurate rendering would be ICAT, or Impact = Consumers x Affluence x Technology. Quoting relevant research, he argued that ‘there’s a weak correlation between global warming and population growth’ and ‘a strong correlation between global warming and wealth.’ Yet he was unable to ‘find any campaign whose sole purpose is to address the impacts of the very rich’ (Monbiot, 2009, p.18) page number). This identifies a major contradiction since a great deal of affluent consumption is learned behaviour based on faulty assumptions about people and their world.

Overall, humanity is undermining the web of life that evolved here and that existed for millennia before it appeared on the scene. It’s unnecessary to buy into any strong version of Gaian mythology to recognise that this living web which has passed through numerous ancient cataclysms and created the very foundations of our own lives and being, is an unparalleled gift from deep time that is – or should be – endowed with incalculable intrinsic value. It is profoundly ironic that some earlier cultures recognised this. It follows that it is incorrect to imagine that those of us who are part of the most technically powerful civilisation in history could imagine that we have the right to destroy or degrade any part of it. Yet whether we look at the story of the oceans, forests, reefs, birds or melting glaciers, different fragments of the same story are reflected back at us. [3]Humanity has become a global force in its own right but is still thinking and behaving as if it lived on a world without limits that can continue to absorb impacts and insults of all kinds without consequence.

The same games of dominance and power that our species has enacted over centuries are still being played out as if the Earth were infinitely resilient. But we now know it is not. Even Machiavelli, an uncompromising master of strategy, recognised the importance of timely foresight as long ago as the sixteenth century. [4] Now the signals of distress from the global system are neither rare nor esoteric but plentiful and increasingly obvious.

There are, of course, large numbers of people living in poverty and diminished means that prevent them from reading the signals of change and dealing with the encroaching global emergency. In many cases they are already dealing with the early manifestations of climate change: unreliable rains, falling or unreliable river flows, vanishing fisheries and so on. Those who live in affluent circumstances have some level of awareness and understanding but, on the whole, choose not to respond. We also know that our civilisation was not only built by exploiting fossil fuels but also continues to rely on them even as the supplies of oil diminish and the costs of the resulting global warming from CO2 pollution escalate. In these circumstances E.O. Wilson’s suggestion that human beings may be hard wired to respond only to short term and immediate stimuli and hence are destined to fail makes some sense. But, fortunately for us, that view is only part of the story. We also need to look more closely at where our responses to global challenges originate and also how they are conditioned through invisible – but immensely powerful – socio-cultural forces.

Let us, however, be clear about one thing. The notion of overshoot and collapse is no longer a distant hypothesis. Rather, it is a structural reality, an unavoidable part of the world in which we live. Yet here we need to register a couple of vital caveats. First, the above analysis is by no means a gloom and doom conclusion but contains within it seeds of considerable promise. Second, the concept of collapse is by no means as monolithic or settled as it may first appear. When used unthinkingly it may be little more than a blanket term that actually conceals a wide range of opportunities for intervention and choice that are, thus far, poorly understood or explored. Fortunately for us, these questions open up in some challenging and surprising directions.

A broader, deeper canvas

Over the years it’s become increasingly clear that common characteristics of climate change deniers, like the evasions of here-and-now decision-makers, and those who blithely dismiss future threats, are not hard to identify. Self-interest, viewed as an expression of ego and pride, plays a huge role, particularly when it remains unexamined and unquestioned. In many cases it is accompanied by narrow-mindedness, an aversion to high-quality information and a lack of interest in humanity’s future. Human characteristics such as these are highly influential but widely overlooked in more conventional economic-, and technology-focused accounts. Such characteristics are, however, neither invisible, nor set in stone.

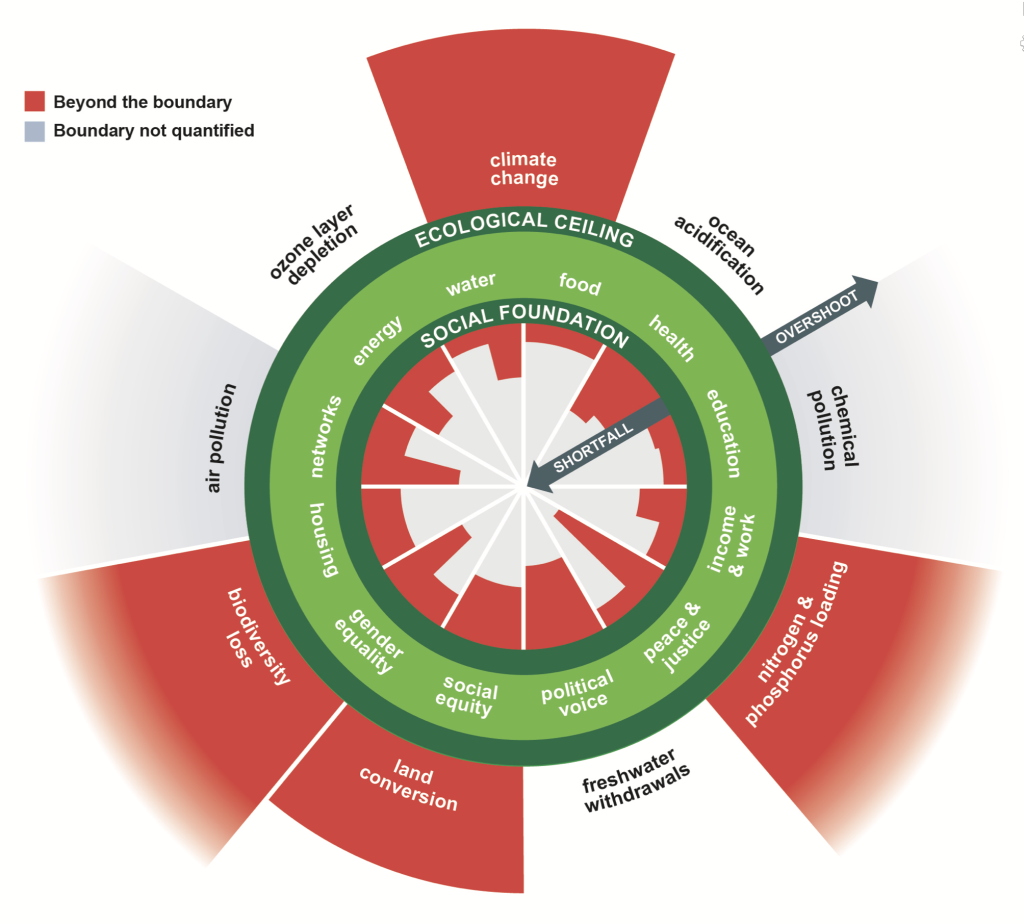

E.F Schumacher wisely noted that problems cannot be understood on the same level upon which they’re first experienced. To appreciate how human attributes directly affect the shifting prospects for humanity requires something more than positive thinking or everyday psychology. It requires an open mind, a depth dimension, respect for quality evidence and an extended timeframe. Overall, a broader, deeper canvas. One of the secrets hidden in plain sight is that the entire human world is constructed by and for people. Moreover, every part of it needs to justify its place or, in other words, be legitimated. It’s a continuing process. This means that, in principle (if not always in practice) every aspect of our world can be revised, re-imagined and re-constituted in the light of changing circumstances. Properly understood this view provides a sound and continuing basis for a huge range of productive social innovations across the board that, taken together, support constructive change (Slaughter, 2022). Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Model is proving to be one of the most productive and widely applied.

Within the futures domain, critical approaches manifestly generated new insights and reinvigorated methods. Yet, over time, what also became clear is that they paid insufficient attention to the human and cultural interiors. By looking more carefully at how individuals, societies and organisations, for example, construct and inhabit these inner worlds (through language, tradition etc) it became easier to clarify why some actors, such corporate executives, political leaders and high-tech oligarchs, acted as they did to deny, delay and impede so many necessary changes in policy and practice.

The tools and methods of integrally informed futures work are useful precisely because they shine new light on these interior realities. They can also reinvigorate earlier methods (see Chapter 6). They help us to understand how values, worldviews, perspectives and states or stages of human development each have a role in producing the consequences we see around us. Climate denialism, the premature dismissal of limits, rigid adherence to the ideology of growth, and many other issues become much clearer when approached in this way. Such methods also helpfully illuminate some of the interior aspects of more humanly compelling futures.

Conclusion: Is collapse inevitable?

If by ‘collapse’ we mean the global system shuts down then – no, it won’t happen — the system will continue to adjust to the impacts created by our species and, as has happened many times before, eventually reach a new dynamic equilibrium. If by ‘collapse’ we mean the sudden termination of human societies, again, this future appears unlikely in the foreseeable future. Some form of human presence will continue, so long as global temperatures remain with a zone habitable to humans.

If by ‘collapse’ we mean that some resources will run out, more species will become extinct and human societies will continue to be battered and bruised by global changes beyond their control then, — yes, this is a very likely future. Most of the ‘heavy trends certainly point in this direction. But ‘very likely’ does not, by any means, mean inevitable. Part of the reason is that we are literally surrounded by resources that, for many reasons, we’ve either overlooked or declined to take seriously. This chapter has, for example, implied that Western culture has proceeded for three centuries with a strong emphasis on empirical knowledge in pursuit of instrumental power. The other ‘half’ of reality (i.e. the human and social interiors) has been widely overlooked, leaving huge gaps in what can be grasped, what projects can be attempted and, as a result, what futures seem likely at any particular time.

So where are we headed? Currently we are clearly heading toward a high-tech dystopia, a damaged, denuded world overrun by non-human, digital devices that, as things stand, we may never fully understand or control. This is precisely where higher—order human capacities of the kind referred to here are most urgently required. Once the interiors are factored back into our evolving picture of the world, we begin to see how out of balance things have been. We notice how conventional taken-for-granted worldviews reality provided so few options beyond an arid business-as-usual. Once we’ve identified the specific domains, values and worldviews from which the mega-crisis arose, everything changes, or could do so. The paucity of view that led to depression, fatalism, avoidance and so can recede into the past. We realise that what any individual or social entity perceives depends upon the internal resources that he, she or they bring to the task. Similarly, by understanding what this means in depth, a truly vast arena of possibilities and real-world options opens up before us.

In summary, overshoot and collapse futures are perhaps best understood as consequences of an exhausted worldview and redundant values. On the other hand, embracing a broader, deeper canvas provides access to human and social resources from which vibrant and humanly compelling futures can emerge.

Notes

The earliest version of this paper appeared as Chapter 3 of Slaughter, R. The Biggest Wake-Up Call in History, Brisbane, Foresight International, 2010. A related version was adapted for inclusion in the August-September edition of World Future Review, Vol 2, No 4, 2010.

[i] Ibid, p. 857. The author cites the collapse of the former Soviet Union as a recent example that fits his particular formulation of the issue. But this is best seen as a relatively minor forerunner of the larger breakdowns to come on a much wider scale.

[ii] For example: uncertainty about climate science, the perceived high cost of action, the tragedy of the climate commons, legitimate unwillingness among the poor to commit etc. Ibid. p. 861.

[iii] The executive summary of Steffan, et al, 2004 provides ample evidence of impacts on a global scale. For example: ‘In terms of key environmental parameters, the Earth System has recently moved well outside the range of the natural variability exhibited over at least the last half million years. The nature of changes now occurring simultaneously in the Earth System, their magnitudes and rates of change are unprecedented in human history and perhaps in the history of the Earth.’ P. 4. http://www.igbp.net/booklaunch/book.html

[iv] ‘When trouble is sensed well in advance it can easily be remedied; if you wait for it to show itself any medicine will be too late because the disease will have become incurable.’ … ‘As the doctors say of a wasting disease, to start with it is easy to cure but difficult to diagnose; after a time, unless it has been diagnosed and treated at the outset, it becomes easy to diagnose but difficult to cure…’ ‘So it is in politics. Political disorders can be quickly healed if they are seen well in advance (and only a prudent ruler has such foresight); when, for lack of a diagnosis, they are allowed to grow in such a way that everyone can recognise them, remedies are too late.’ Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, 1516 (Penguin, 1961, p 12).

References

Diamond, J. (2005). Collapse: How societies choose to succeed or fail. Viking.

Eastin, J. Grundmann, R., & Prakesh, A. (n.d.). The two limits debates: ‘Limits to growth’ and climate change. [Unpublished manuscript], Elsevier, Futures,

Kempf, H. (2008). How the rich are destroying the Earth. Green Books.

Lovelock, J. (2006). The revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth is fighting back – and how we can still save Humanity. Allen Lane.

Machiavelli, N. The Prince, London, Penguin, 1961 (Original work published in 1516).

Meadows, D., Meadows, D., & Randers, J. (1972). The limits to growth. Universe Books.

Meadows, D., Meadows, D., & Randers, J., (1992). Beyond the limits. Earthscan.

Meadows, D. Meadows, D., & Randers, J. (2005) Limits to growth – 30 Year Update. Earthscan.

Monbiot, G. The same people always get dumped on, Guardian Weekly, 2nd October, 2009a, p 18-19.

Oxfam International (2012). A safe and just space for humanity: Can we live within the doughnut? [report]. Oxfam discussion papers. https://oi-files-d8-prod.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/file_attachments/dp-a-safe-and-just-space-for-humanity-130212-en_0_4.pdf

Randers, J. (2008). Global collapse: Fact or fiction? Futures 40, 853-864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2008.07.042

Rockstrom, J. , Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F.S., Lambin, E.F., Lenton, T.M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H.J., Nykvist, B., de Wit, C.A., Hughes, T., van der Leeuw, S., Rodhe, H., Sörlin, S., Snyder, P.K., Costanza, R., Svedin, U., … Foley, JA (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461 (7263), 472-6.

Science Policy Research Unit, (1973). The Limits to Growth Controversy, Futures, 5(1).

Steffen, W., Sanderson, Tyson, P.D., A., Jäger, J., Matson, P.A., Moore III, B., Oldfield, F., Richardson, K., Schellnhuber, H.-J., Turner II, B.L., & Wasson, R.J. (2004). Global Change and the Earth System. IGBP Secretariat. http://www.igbp.net/download/18.1b8ae20512db692f2a680007761/1376383137895/IGBP_ExecSummary_eng.pdf

Turner, G. A. (2008). Comparison of the limits to growth with thirty years of reality. (Report). CSIRO. doi.org/10.4225/08/5a6f615edf3ce

Ward, P. (2009, June 17). Gaia’s evil twin. New Scientist, 28-31.

- Randers 2006, p857 - The author cites the collapse of the former Soviet Union as a recent example that fits his particular formulation of the issue. But this is best seen as a relatively minor forerunner of the larger breakdowns to come on a much wider scale. ↵

- Randers, 2008, p. 861. For example: uncertainty about climate science, the perceived high cost of action, the tragedy of the climate commons, legitimate unwillingness among the poor to commit etc. ↵

- The executive summary of Steffan, et al, (2004, p.4) provides ample evidence of impacts on a global scale. For example: ‘In terms of key environmental parameters, the Earth System has recently moved well outside the range of the natural variability exhibited over at least the last half million years. The nature of changes now occurring simultaneously in the Earth System, their magnitudes and rates of change are unprecedented in human history and perhaps in the history of the Earth.’ ↵

- ‘When trouble is sensed well in advance it can easily be remedied; if you wait for it to show itself any medicine will be too late because the disease will have become incurable.’ … ‘As the doctors say of a wasting disease, to start with it is easy to cure but difficult to diagnose; after a time, unless it has been diagnosed and treated at the outset, it becomes easy to diagnose but difficult to cure…’ ‘So it is in politics. Political disorders can be quickly healed if they are seen well in advance (and only a prudent ruler has such foresight); when, for lack of a diagnosis, they are allowed to grow in such a way that everyone can recognise them, remedies are too late.’ (Machiavelli, 1516/1961, The Prince, p. 12). ↵