Afterword

JP Jakonen

This chapter is original work by JP Jakonen, and appears for the first time in this text. It is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

The fallacy of consensus reality: A multi-storey building model as a basis for systemic change

Abstract

The fallacy of consensus reality is built on forgetting our interior dimension. This dimension causes us see both the same reality and a different View of that reality. When discussing a topic, we should first attempt to discern the View of those discussing the topic. Human beings each have their unique “Kosmic address” as they inhabit our planetary building. Failing to see that leads to unfruitful dialogue, worldview neglect, and hate speech inspired by a lack of empathy. This happens on all levels, as our unique address offers us a particular View (based on the floor/level of the building we are currently residing at) and a particular Perspective (based on our native way of looking at reality). Most of these feel mutually exclusive due to the binary nature of the Views from each floor. The View from Floor 5 is often the first where all the previous Views start to make evolutionary sense. This decreases the need to “do something” about them, and instead understands that optimal life conditions for translational and transformational evolution exist on each Floor, each with their corresponding View.

Floors and Views

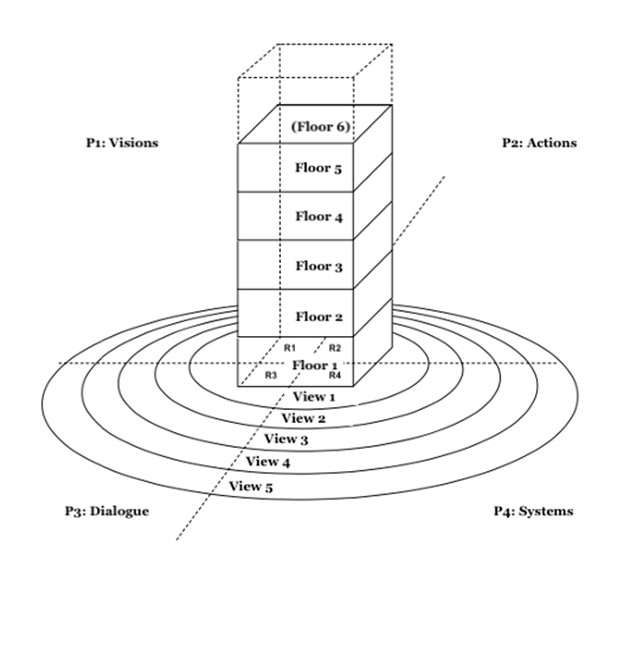

As this approach is rather novel and contains terms with specific meanings, let’s start by defining the two core concepts and offering a visual analogy that binds them together. The concepts are Perspectives, of which there are four, and Views, of which there are five. Perspectives can be compared to rooms in a house that has many floors. We can enter each of the rooms at each of the floors and take in the Perspective available from that room. That Perspective is always colored by and seen through the View that is given as we ascend the building. The following picture illustrates the idea.

Floor 1 offers us a View that enables us to see our own front yard, so to speak. It focuses mainly on me and mine, due to our underlying preoccupation with ourselves. When the limitations of that View untenable, evolution offers us steps to take it wider, as we climb and grow to the next Floor.

Floor 2 offers a View of belonging to a wider whole. It is as if now we can see the yard of the whole building, our common, shared lawn, that requires us to relinquish our self-centeredness in order to belong to this larger group. This View is often called tribal or ethnocentric. In psychology it is referred to as pre-conventional, a View comprised of the conventions of the chosen group. When the limits of this View start to become too painful, evolution offers another flight of stairs.

Floor 3 offers a way of seeing that all the yards in all the buildings all over the world are not so different after all. It offers a worldcentric way of understanding reality. For the first time universal morals, despite the religious, ethnic or intellectual denominators of the group emerge. Since a worldcentric View is only possible from the third Floor, it is a momentous leap forward in moral and cognitive development. Yet as with all Views, problems or limitations arise. Floor 3, however, is the home base of Views that pursue growth without limits and a consumerist lifestyle that no one really needs. It is the modern worldview, that again gives rise to yet a new set of stairs. In this case it leads up to the postmodern View that becomes available as we enter the fourth Floor.

Floor 4 is the View that allows us see the limitations of what happens if we only concentrate on yards, instead of what has been omitted from the grand narrative of buildings and yards. It shows us how the modern world has trampled marginalized peoples and their ways of being under its colonial feet. It opens a sensibility to suffering that is experienced by few, and perhaps, as the limits of its own View come online, at the expense of many. In its healthier versions this is the View of enlightened academics, good-hearted hippies and structuralists. Its unhealthy versions are sometimes referred to as the “mean green meme”, or “woke racism”.

Floor 5 has emerged more recently and, depending on the individual observer, sometimes called integral, teal or second tier. It has been described as offering the first View where all the previous Views are accepted as real tenants of the same common building. From here, the Views from 1 to 4 are seen as what they are: Views to be taken seriously but not as solid and fixed. Their evolutionary nature becomes apparent, as they are seen leading holistically to each other, offering a natural holarchy of growth towards ever more expansive Views and deeper moral sense of planetary citizenship (Salonen et al, 2023). A view from Floor 5 helps us grasp the basic fact that the rent is identical for all the tenants, regardless of the Floor they occupy. Some folks see a wider, more expansive View, while other see a narrower, more restricted View, and that’s just the way it is. Floor 5 offers a seemingly paradoxical combination of evolutionary empathy and optimism based on both seeing the world as it is – a multi-storey building of Floors and Views – and as a continuum of both vertical and horizontal growth possibilities.

Rooms and Perspectives

Perspectives are like rooms in a house. In order to see what is available from a particular room, we must enter the room. Unlike Floors, the rooms are always available for everyone to walk in, as they exist in each Floor, with no vertical development needed to access them. They are akin to languages that we can learn. The word “dog” refers to the same thing in different languages, but we must learn to say the word in Finnish if we want to refer to a dog in Finland. The same thing with Perspectives. We can only enter the world of Visions (P1), i.e. inner, felt reality, with a certain degree of truthfulness. We can speak about our interior-personal perspective with varying degrees of truthfulness. This is the coinage of the realm where phenomenology, psychology and therapy meet. The same applies to P2, the world of exterior-personal Actions. In order to produce measurable results in fixing a car, investing in stocks or removing an appendix, we need to be able to act, to do and to measure the visible results of the action. Truthfulness does not apply here. Amounts do. Phenomenological truthfulness will not make a car run, if there is air in the hydraulics.

P3 and P4, the perspectives of interior-collective Dialogue (P3) and exterior-collective Systems (P4), have again their own language. In order to make agreements, we must enter the language of interpersonal exchange of ideas in the public sphere. We must enter a room where this language game is being played, and the only way to do that is to learn the language. The same, again, applies to the perspective of Systems, which are the exterior-collective dimensions of our being in the world. Planetary systems, governments, star clusters and universities are all systems, operating under certain rules. To understand these systems, we need to learn their language, since other languages only get us so far in building better systems, frameworks and intermeshing structural architectures that support the visions (P1), actions (P2) and dialogue (P3) of living beings inside those systems.

What does it feel like to have a View?

If Perspectives are like languages with common reference points – easy to understand, but a bit cumbersome to learn – then Views are like cultures that sometimes feel as if they were from another planet. Imagine being able to speak Swahili, but only having learned it from a book in a Scandinavian country. Imagine, then, being transported to a hut in a village in Kenya, as if in a flash, and finding you there. You can speak the language – the Swahili word for a dog points to an actual dog walking in the village – but the dog itself could have a different function in the language-game system than in the place you were suddenly transported from. It could represent an object of religious reverence, a pet, or a meal, depending on the surrounding system, life conditions and the worldview that arises to meet the entire set of circumstances (Beck 1996).

Then imagine being transported to Germany. Again, you can speak the language, but you have learned to speak German in a small island in the Pacific Ocean. Then, again as if in a flash, you are transported to a country where you know the language, but the language game system has different reference points than the place you came from. “A holiday” in Germany might mean two weeks off from work a year, where “a holiday” in your native language-game system has no meaning at all! Your native system with its life-conditions have birthed a worldview that has no use for “holiday” as a rhythmic interval for otherwise all-consuming way of living that is our modern work life.

These examples may sound far-fetched, but the idea behind them is straightforward. Human beings do not all see the same world. Rather, our perceived reality is brought to life by our instruments of perceiving. The structures of consciousness determine the phenomena that appear in that consciousness. These instruments and structures are both horizontal, varying in Perspectives of the world (P1, P2, P3, P4), and vertical, varying in Views (View 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …) of the world. Perspectives can be changed by learning a new language. Views change as we grow into a new interior culture, usually referred to as a worldview or a level of cognitive development. In the Figure these are represented by a multi-storey building, with Floors giving rise to a certain View, and rooms offering a certain Perspective.

Conclusion

A few concluding notes. We can be at a certain Floor and have access to all the rooms. Usually, one of the rooms is closer to our way of being than others, but we still can have varying levels of access to all of them. Things are, however, more challenging from within Views that are available to us. We usually have a worldview base that is centered around one Floor. That means that our worldview is, more or less, at one point in time, an either/or type of occurrence. We either see the View 1 of egocentrism, or the View 2 of Ethnocentrism, but we cannot inhabit both Floors at the same time. In healthy cognitive growth we retain the access to previous floors, but as they are transcended, our sense of meaning making is no longer restricted by them. We still have (or, in healthy growth, should have) access to our egoistic tendencies, but they are superseded our belong to a wider, more expansive group than one’s own individual ego. The leap to the third Floor opens up the View of all groups, and a universal moral recognition that all groups are equal, whatever their attributes may be.

Throughout the building arise different structures, like elevator shafts that can reach all the way to the top (although, strictly speaking, there’s no top, as evolution has no obvious end point). Using the analogy, one of the attributes (“Cognition”) can have its elevator access Floor 5, offering a systems view of reality. Another attribute (“Emotional Intelligence”) can reach as far as Floor 3, which tends to make those with these attributes rather tedious companions. These are sometimes called multiple lines of intelligence (Gardner 1983; Wilber 2000). Other elements such as states of consciousness and typological structures are relevant here, but for the same of brevity they are not addressed in this introductory piece.

The multi-storey building offers a visual analogy of the human element in all systems. It suggests that reality does not offer a universal consensus, as it is always seen, or created, from a certain “kosmic address”. There is no reality as such. There is a reality of Views and Perspectives, which in this model, depicts 24 variations. This helps us to understand diversity in communication, and also how it takes effort to understand each other in a genuinely empathetic way, taking the point of view of another human being and accepting it as it is. Despite the odd-sounding language and the foreign culture it is embedded in, it offers room for horizontal and vertical evolution. Any theory of systems not taking this into account will be less than sufficient.

References

Beck, A.T. (1996). Beyond belief: a theory of modes, personality and psychopathology. In P.M. Salkovskis (Ed.), Frontiers of cognitive therapy (pp. 1-25). Guilford Press

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: the theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books

Salonen et al. (2023). Who and what belongs to us? Towards a comprehensive concept of inclusion and planetary citizenship. International Journal of Social Pedagogy, 13(1), 5

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology: consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Shambala