6 Chapter 6 – Generative AI and the future of education: Ragnarok or reformation? A paradoxical perspective from management educators

A paradoxical perspective from management educators

Weng Marc Lim; Asanka Gunasekara; Jessica Leigh Pallant; and Jason Ian Pallant

Generative AI and the future of education: Ragnarök or

reformation? A paradoxical perspective from

management educators

Weng Marc Lim a,b,c,*, Asanka Gunasekar b, Jessica Leigh Pallant b, Jason Ian Pallant b, Ekaterina Pechenka d

a Sunway Business School, Sunway University, Sunway City, Selangor, Malaysia

b School of Business, Law and Entrepreneurship, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia

c Faculty of Business, Design and Arts, Swinburne University of Technology Sarawak Campus, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

d Learning Transformations Unit, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia

* Corresponding author. Sunway Business School, Sunway University, Sunway City, Selangor, Malaysia.

E-mail addresses: lim@wengmarc.com, marcl@sunway.edu.my, marclim@swin.edu.au, wlim@swinburne.edu.my (W.M. Lim), agunasekara@swin.edu.au (A. Gunasekara), jlpallant@swin.edu.au (J.L. Pallant), jipallant@swin.edu.au (J.I. Pallant), epechenkina@swin.edu.au (E. Pechenkina).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100790

Received 9 February 2023; Received in revised form 16 February 2023; Accepted 17 February 2023

Available online 1 March 2023

1472-8117/© 2023 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Academic integrity

Bard

ChatGPT

Critical analysis

DALL-E

Ethics

Future of education

Generative AI

Generative artificial intelligence

Education

Educator

Management education

Management educator

OpenAI

Paradox

Paradox theory

Ragnar¨ok

Reformation

Transformation

Transformative education

ABSTRACT

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) has taken the world by storm, with notable tension transpiring in the field of education. Given that Generative AI is rapidly emerging as a transformative innovation, this article endeavors to offer a seminal rejoinder that aims to (i) reconcile the great debate on Generative AI in order to (ii) lay the foundation for Generative AI to co-exist as a transformative resource in the future of education. Using critical analysis as a method and paradox theory as a theoretical lens (i.e., the “how”), this article (i) defines Generative AI and transformative education (i.e., the “ideas”), (ii) establishes the paradoxes of Generative AI (i.e., the “what”), and (iii) provides implications for the future of education from the perspective of management educators (i.e., the “so what”). Noteworthily, the paradoxes of Generative AI are four-fold: (Paradox #1) Generative AI is a ‘friend’ yet a ‘foe’, (Paradox #2) Generative AI is ‘capable’ yet ‘dependent’, (Paradox #3) Generative AI is ‘accessible’ yet ‘restrictive’, and (Paradox #4) Generative AI gets even ‘popular’ when ‘banned’ (i.e., the “what”). Through a position that seeks to embrace rather than reject Generative AI, the lessons and implications that emerge from the discussion herein represent a seminal contribution from management educators on this trending topic and should be useful for approaching Generative AI as a game-changer for education reformation in management and the field of education at large, and by extension, mitigating a situation where Generative AI develops into a Ragnarok that dooms the future of education of which management education is a part of (i.e., the “so what”).

1. Introduction and background

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) is a distinct class of AI and an incredibly powerful technology that has been popularized by ChatGPT.1 Developed by OpenAI, ChatGPT acquired one million users in five days and reached 100 million users two months after it was made public in November 2022, setting the record for the fastest-growing consumer application (Hu, 2023).2 As a chatbot driven by Generative AI,3 ChatGPT shocked the world with its ability to understand complex and varied human languages and generate rich and structured human-like responses. DALL-E is another example of Generative AI developed by OpenAI that works in a similar way to ChatGPT albeit with digital images as outputs. Both ChatGPT and DALL-E are products of deep learning (OpenAI, 2023), which is a subset of machine learning that mirrors the human brain in learning and responding to data, information, and prompts (Sahoo et al., 2023). Google has responded rapidly by announcing their own Generative AI, Bard, which is powered by next-generation language and conversation capabilities such as Language Model for Dialogue Applications (LaMDA) (Pichai, 2023). Therefore:

Generative AI can be defined as a technology that (i) leverages deep learning models to (ii) generate human-like content (e.g., images, words) in response to (iii) complex and varied prompts (e.g., languages, instructions, questions).

It is also important to distinguish Generative AI with related concepts. In line with our definition, it is worth noting that Generative AI has the unique ability to not only provide a response but also generate the content in that response, going beyond the human-like interactions in Conversational AI (see Lim, Kumar et al., 2022). In addition, Generative AI can generate new responses beyond its explicit programming, whereas Conversational AI typically relies on predefined responses. However, not all Generative AI is conversational, and not all Conversational AI lacks the ability to generate content. Augmented AI models, such as ChatGPT, combine both Generative and Conversational AI to enhance their capabilities. They differ with Generic AI, for example, Scite (2023), which utilizes natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning to determine whether a scientific publication supports, refutes, or mentions a claim related to a specific query, as well as the citation statements reflecting that citing pattern. Notwithstanding these differences, we wish to shine the spotlight on Generative AI in this article in response to the great debate of its use in education that has been sparked by its content-generating capability. As a group that is often accused as conservative and resistant to change (Marks & Al-Ali, 2022), it is unsurprising to see many educators voicing concerns about Generative AI, particularly around assessment and ethical issues such as originality and plagiarism (Chatterjee & Dethlefs, 2023; Stokel-Walker, 2022). At the time of writing, it is noteworthy that many governments and schools have banned Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT amid fears of AI-assisted cheating (ABC News, 2023; Dibble, 2023; Lukpat, 2023) while the same is observed in academic publishing (Nature, 2023).

If we recall, COVID-19 supposedly forced education worldwide into digital transformation. Educators and institutions ‘pivoted’ to online or blended classes, and many have continued with these practices even as campuses have reopened (Holden et al., 2021). Yet, this transformation remains imperfect. Some, if not many, educators still rely on basic technologies such as online game-based learning platforms (e.g., Kahoot and Mentimeter) and videoconferencing tools (e.g., Microsoft Teams and Zoom) to replicate physical into virtual lessons (Lowenthal et al., 2020).

The above observations are critical as they provide two noteworthy implications (i.e., the “issues”): one, the transformation of the education sector remains sluggish, and two, the state of transformative education remains underwhelming, whereby:

Transformative education can be described as education that (i) is transformative4 (i.e., the “idea”) in its (ii) process5 (i.e., the “how”) and (iii) product6 (i.e., the “what”) in response to (iv) grand challenges7 (i.e., the “so what”).

With Generative AI rapidly emerging as a transformative innovation along the likes of the internet and the smartphone, there is now a golden opportunity to truly reimagine and transform the future of education (i.e., the “importance”), and with the likes of ChatGPT co-authoring and publishing journal articles (e.g., Ali & OpenAI Inc, 2023; O’Connor & ChatGPT, 2023),8 educators must inevitably transition into a future of education where Generative AI is embraced rather than shunned (i.e., the “urgency”). As with any trending issue such as COVID-19 (Lim, 2021) and the Ukraine and Russia conflict (Lim, Chin et al., 2022), Generative AI has, inevitably, attracted plenty of interest among academics (e.g., educators, researchers), industry professionals, and policymakers, resulting in a great debate (i.e., the “relevance”), though often times in a fragmented manner, for example, either from the perspective of opportunities and proactive pathways (Dowling & Lucey, 2023) or threats and reactive regulations (Nature, 2023) (i.e., the “gap”).

Given the notable tension transpiring in the field of education, there is a need for a critical discourse that can accommodate both the concern and excitement for Generative AI in a well-balanced manner (i.e., the “necessity”). In this regard, this article assumes the position that Generative AI is here to stay and thus endeavors to reconcile the great debate on Generative AI with insights, lessons, and implications for the future of education (i.e., the “aim”). To do so, this article adopts critical analysis as a method and paradox theory as a theoretical lens to deliver on its aim, wherein the former is a method that supports tackling known issues using the 3 E s of exposure (e.g., readings), expertise (e.g., as educators and researchers), and experience (e.g., users of Generative AI) (Kraus et al., 2022) while the latter is a theory that acknowledges the existence of contradictory yet interrelated elements and thus offers a basis to engage, reconcile, and produce a well-balanced perspective to manage competing elements (Yap & Lim, 2023) (i.e., the “how”). In doing so, this article offers a seminal contribution from the perspective of management educators and highlights the potential for Generative AI to co-exist as a transformative resource in education, thereby supporting endeavors that approach Generative AI as a game-changer for education reformation, and by extension, mitigating a situation where Generative AI develops into a Ragnarok that dooms the future of education of which management education is a part of (i.e., the “so what”).

2. The paradoxes of generative AI and the future of education

Current discourse surrounding Generative AI and its impact on education tends to focus on the challenges it creates for educators (e.g., Stokel-Walker, 2022; Terwiesch, 2023) or the opportunities it presents for educators and students alike (e.g., Pavlik, 2023; Zhai, 2022). At their extremes, the former position views Generative AI as a form of Ragnarok, bringing about the destruction of the education system, while the latter sees it as a reformation, bringing a new dawn of accessible information and automation to enhance the footprint and quality of education. These two views highlight the inherently paradoxical nature of Generative AI and its role in education; it could destroy some education practices while at the same time supporting them. To explore these conflicting ideologies, we present four key paradoxes of Generative AI in education, including some hands-on practical examples, which, in turn, offer useful lessons and implications for the future of education.

2.1 Paradox #1: Generative AI is a ‘friend’ yet a ‘foe’

Early research suggests that ChatGPT, as a specific example of Generative AI, can be used as a tool to facilitate knowledge acquisition and support writing tasks such as codes, essays, poems, and scripts (Chatterjee & Dethlefs, 2023; Terwiesch, 2023; Zhai, 2022). Within a short period, ChatGPT has demonstrated its remarkable ability to generate human-like responses in almost all disciplines. Feedback from early users suggest that many are surprised and impressed by how fast the tool learns from and responds to human interactions (Terwiesch, 2023). Though technically ‘artificial’ (i.e., AI), Chatterjee and Dethlefs (2023, p. 2) has referred to Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT as a friend, a philosopher, and a guide because of the ‘humanely’ way such tools interact and generate responses, which, in turn, opens up opportunities for educators to diagnose gaps in student learning and students to gain timely feedback using these tools (Zawacki-Richter, Marín, Bond, & Gouverneur, 2019). Yet, when elevation of knowledge is concerned, Generative AI tools may pose challenges for educators, especially those in research-intensive higher education institutions, in ascertaining whether knowledge presented by students, and even peers, are truly novel (e.g., new insight emerging from a critical analysis of information) or, in fact, recycled (e.g., basic copying and pasting to advanced paraphrasing of AI-generated answers). Critics such as Noam Chomsky (Open Culture, 2023) have suggested that Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT are essentially ‘high-tech plagiarism’ and ‘a way of avoiding learning’, but is this truly the case, or should we be viewing this an opportunity to rethink how we learn and evaluate information?

Moreover, the diffusion of Generative AI at scale could potentially spell the end of some assessment types such as essays (Zhai, 2022). After all, if a Generative AI tool like ChatGPT can offer detailed and human-like responses to advanced essay questions, the what is the role of human learning and insight in responding to these types of assessments? As an example of this challenge, ChatGPT successfully passed graduate-level business and law exams (Kelly, 2023), and even parts of medical licensing assessments (Hammer, 2023), which has led to suggestions for educators to remove these types of assessments from their curriculum in exchange for those that require more critical thinking (Zhai, 2022). In this regard, the advancement of technology through the rise and proliferation of Generative AI tools could elevate the rigor in the assessment of knowledge, though it could also threaten to make such assessment redundant in at least three instances: (i) when no suitable solution can be found, (ii) when a solution is found but unavailable, or (iii) when a solution assesses only the process (e.g., questioning) but not the product (e.g., answer). Counterintuitively, the rise of Generative AI could also reinvigorate the debate about the relevance of assessments that supposedly do not belong in higher education such as multiple-choice questions (Young, 2018), which when designed in a way that induce higher-order critical thinking 10 could become a potential solution that not only test students’ mastery of specific skill sets needed to resolve complex issues but also grade the answers when Generative AI is paired with automated solutions. Though the capability of AI is poised to advance rather than regress over time, history suggests that new discoveries and thus the evolution of humanity will inarguably follow,11 thereby enabling humans to become better users and managers, not slaves, of technology.

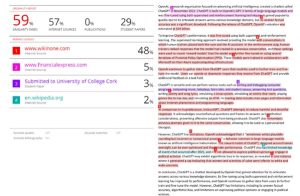

Nonetheless, it is important to note that Generative AI has its flaws despite its ability to inform and generate human-like responses. To illustrate, we asked ChatGPT two simple questions about recent events.12 The first question requested for an answer pertaining to the winner of the Australian Open in 2023, an event that occurred between January 8 to 29, 2023 (Fig. 1). ChatGPT apologized that it did not have the answer and explained that its training data only goes up until 2021. Yet, ChatGPT was able to provide an answer to the second question relating to the winner of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, an event that took place between November 20 to December 18, 2022 (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, it should be noted that France was an incorrect answer as the real winner was Argentina. Through these illustrations, it can be deduced that Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT may be (i) limited to non-current data, which, in turn, can cause its users to suffer from (ii) knowledge gaps, or worse, (iii) false information when the tool misinterprets prompts, or (iv) turns dishonest, if any how possible. Yet, with companies such as Google venturing into Generative AI and leveraging its resources to address the gap of currency in data by connecting Generative AI tools to the world of information via the search engine and using such information for training, other issues may arise, for example, unlike any pre-determined training data that is carefully curated and managed, the data sourced directly from the search engine for training and informing Generative AI may be subject to information disorders such as disinformation and misinformation, thereby raising a different set of problems. Supporting the notion that Generative AI is not perfect nor of premium quality at this juncture, a recent study by University of Pennsylvania (Terwiesch, 2023) found that ChatGPT responses only received B to B- grades for an Operations Management exam in the MBA. Further scrutiny of the capability of Generative AI to paraphrase also indicates that the output returned or work performed could appear decent at a glance but may be, in reality, unable to fully meet requirements and pass detailed checks by plagiarism detection software such as Turnitin. This can be seen in Fig. 3, which shows that the requirement of returning a paraphrased essay with a minimum of 500 words was not met and that the paraphrased essay had a similarity index of 59%.13 Due to these limitations, students who rely on Generative AI alone could obtain true information, but they may not necessarily do well in their assessments; instead, they will need to re-check, re-work, and meaningfully build on the content developed by Generative AI to stand a better chance of performing well and securing a higher grade.

Last but not least, Generative AI can empower progress in a good way when the information it provides is employed by its users ethically or with good intention. Nonetheless, the opposite is also true when the information that Generative AI tools provide is used unethically or with ill intention. Yet, the example shown in Fig. 2 reveals evidence that misinformation could be propelled by Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, which, in turn, suggests that even users of such information, with good intention, could also turn into culprits (e.g., disseminator of fake news). While the onus would inarguably be on users to verify the validity of the information provided by Generative AI tools, the reality is that many people continue to remain ignorant to false information, which may be due in part to cognitive bias (e.g., belief-conforming information, popularity and persistence of false information) and overreliance on heuristics (e.g., headlines) to interpret information (Center for Information Technology and Society, 2023).

2.2 Paradox #2: Generative AI is ‘capable’ yet ‘dependent’

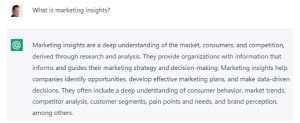

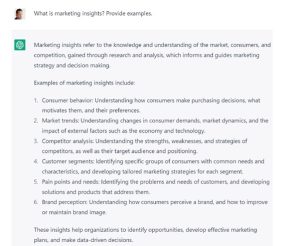

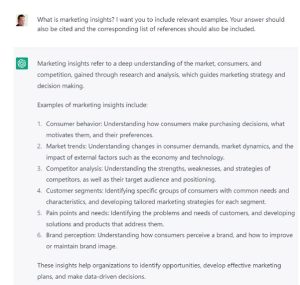

Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT have proven to be quite capable in generating responses (e.g., text) across a myriad of areas (e. g., topics) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Fig. 3) and prompts (e.g., instructions, questions) (Figs. 4 and 5). This can also be seen in its access to a rich collection of resources (e.g., books) and its responses that are adept (e.g., structured) anti-timely (e.g., immediate) (Fig. 6). In this regard, the capability of Generative AI could be measured by how well its tools such as ChatGPT can respond to the prompts given in a way that is complete, coherent, and correct (i.e., the 3Cs). Indeed, these capability traits resonate well with those typically shown by humans who are deemed to be capable (e.g., efficient, skillful, and resourceful) (Ferraro et al., 2023; Rychen & Salganik, 2003).

Yet. apart from its ability to search, structure, and showcase (i.e., the 3Ss), Generative AI is far from being highly independent; in fact, the responses that it generates is highly dependent on the inputs that it receives. For instance, Generative AI is quite dependent on the prompts that it receives, both in terms of quantity and quality. To illustrate, we asked ChatGPT a question with and without specific instruction(s) and evaluated the responses that were returned. Fig. 4 indicates that ChatGPT is indeed capable of providing a decent answer when asked a question, in this case, the meaning of marketing insights. However, without any specific instruction, the answer provided appears to be sharp and succinct. Fig. 5 shows that ChatGPT is also capable of providing a more elaborate answer when it is instructed to do so. Perhaps the most interesting observations could be found in Fig. 6, where ChatGPT, in its present version (i.e., ChatGPT Jan 30 Version), does not have the capability to (i) cite despite being instructed to do so and (ii) unable to correctly choose the references to support its answers in its entirety (e.g., Hair et al. (2016) is a methodological not a subject-matter reference). These limitations suggest that the responses from Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT cannot be fully relied upon in its entirety, especially at this juncture, and thus should be treated with caution. The manifestation of the latter (i.e., the overconfidence in reference selection) is

Fig. 1 ChatGPT acknowledging its limitations

Fig. 2 ChatGPT revealing an incorrect answer when it disregards its limitations

Fig. 3. Similarity index of a paraphrased essay about ChatGPT by ChatGPT based on a Turnitin plagiarism scam.

also noteworthy and could be explained by the Dunning-Kruger effect, which occurs when an entity’s lack of knowledge and/or skills causes that entity to overestimate its capability, resulting in completion yet underperformance of tasks (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). Specifically, AI-driven tools are being fed information and thus can only generate predictive responses to prompts based on the information it has already been fed. This observation suggests that Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT are dependent on the training that it receives to generate its responses (Chatterjee & Dethlefs, 2023; Terwiesch, 2023). Therefore, a probable reason for its limitations.

Fig. 4 ChatGPT providing a sharp and succinct response

Figure 5. ChatGPT providing an elaborate response

References:

- Kotler, P., & Kotler K. L. (2012). Marketing management. Pearson Education.

- Vavra, T.G. (2017). Marketing research essentials. John Wiley & Sons.

- Malhotra, N.K. (2018). Marketing research: An applied orientation. Pearson.

- Malhotra. N.K., & Birks, D.F. (2015). Marketing research: An interdisciplinary approach. Pearson

- Hair, J .F., Hult, G. T.M., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

Fig. 6. ChatGPT providing an elaborate response with references

could be attributed to the tool’s algorithm predicting the most likely combination of words rather than being able to objectively review and cite a specific source. In this regard, the same ignorance of ignorance that is seen in humans could also be observed in AI, therebyshowing early evidence that may extend and support the theoretical generalizability of the said effect from humans to bots.

2.3 Paradox #3: Generative AI is ‘accessible’ yet ‘restrictive’

The next paradox relates to the accessibility of Generative AI. The mission of OpenAI, the developer of Generative AI tools like ChatGPT and DALL-E, is to ensure that Generative AI benefits all of humanity (OpenAI, 2023). In line with this mission, ChatGPT was made freely accessible to its users upon launch to support the democratization of knowledge (Pavlik, 2023). This has the potential to not only pave the way for educators to access deep learning tools to curate knowledge, but also improve equity and access to education. For instance, one of the major issues faced by higher education students from non-English speaking backgrounds are language barriers hindering their academic success (Cheddadi & Bouache, 2021), which could induce the fear of missing out (Alt, 2017) and open up greater possibilities of getting entangled in academic integrity issues (e.g., unintentional plagiarism) (Fatemi & Saito, 2020). With Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, we could argue that its features such as language editing and translation, ability to continuously improve content with human prompts, and speed in providing a response may provide a somewhat leveled playing field for students.

However, Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT could be made freely and readily available only for a limited period and include a paid subscription service (Chatterjee & Dethlefs, 2023). This not only stands against the democratization of knowledge but could also widen the impact of socio-economic gaps by reducing access for those who cannot afford the premium fee and prioritize access for those who can. Hence, the inherent paradox is that while Generative AI tools have the ability to democratize access to knowledge, the ability to access these tools may be limited based on available resources, thereby creating further equity and accessibility issues. It is therefore a must to carefully consider the possible negative implications on students who cannot afford to regularly access the tool. Similarly, can or should we expect academic institutions to purchase rights to access these tools on behalf of their students so that they can embrace the use of AI in education? What will be the cost and can every academic institution in the world from the Ivy Leagues in developed countries to the public- and self-funded institutions in developing and less developed nations afford it? These are pertinent questions that highlight the importance of engaging and managing transformative innovation such as Generative AI in a way that would make the world—not part of it—a better place.

2.4 Paradox #4: Generative AI gets even ‘popular’ when ‘banned’

With the rapid rise and popularization of ChatGPT, education bodies around the world have been quick to declare a stance on Generative AI tools. For example, the Department of Education in the Australian states of New South Wales and Queensland have announced that they will ban ChatGPT using a firewall (ABC News, 2023) while the same has taken place in New York City public schools (Lukpat, 2023). Others such as the Department of Education in the Australian state of Victoria has banned access to ChatGPT, citing the terms of use that is restricted to those above the age of 18 (Jaeger, 2023), which most school-going students are not. These bans represent attempts to control the use of the technology, either permanently or temporarily, while policies and regulations are developed or revised.

Yet, paradoxically, banning Generative AI tools could have a detrimental impact, which may be reasoned in two major ways. The first is the Streisand effect, which stipulates that attempts to censor, hide, or remove something can lead to the unintended consequence of increasing awareness and interest (Jansen & Martin, 2015), and the second is psychological reactance, whereby restrictive practices can also motivate people to react because people generally do not like being told they cannot do or have something, especially if it feels arbitrary or unfair (Brehm, 1989). This is a particularly relevant issue to consider given that several public schools are banning the technology, yet it is still available to many private school students, which can lead to further disparity in access to resources for public versus private school students while increasing their psychological reactance through both emotional and behavioral outlets.

There are similar parallels to bans that educational institutions have attempted to place on other technologies such as mobile or smart devices in classrooms. In most cases, more positive outcomes have been generated when educators have sought to utilize and integrate these technologies rather than banning them (Nikolopoulou, 2021). Similarly, organizations are often limited in the extent to which they can enforce such bans. For example, the ban on the TikTok social media app in the US colleges only applies to government-issued devices and college-supplied WiFi (Paul, 2023). Despite this ban, and even being warned about the potential for private data collection by the platform, users are not deterred from engaging with the platform (Harwell, 2023).

To this end, a paradox of Generative AI that manifests here is that attempts to ban or limit its use could have a conflicting effect and may actually increase its usage among students through heightened attention and psychological reactance. Like other recent technologies, educators and institutions may be more successful at minimizing the negative impacts of Generative AI by embracing its use and formally including ways to leverage it within curriculums. Indeed, some higher education intuitions have chosen to encourage and promote the ethical use of AI-generated content rather than engaging in blanket banning (e.g., Monash University, 2023), which we believe might be the point where the debate would converge in the future.

3. Concluding remarks, lessons, implications, and future directions

The rise of Generative AI may seem like a cause for panic, amid a slew of alarmist articles and the rapid bans by several educational bodies and institutions. However, due to multiple paradoxes that these tools create, we argue that Generative AI is not Ragnarok but rather a transformative resource that educators and students can draw on in teaching and learning. Raising awareness of these tools, using them together in class, and leading discussions with students about their pros and cons offer a more sustainable way forward than either banning these tools or making them central to entire curriculums.

As with governance of student data collection and usage, educational bodies and institutions need to be up to date on the latest AI developments and update their relevant policies and guidelines accordingly. Reiterating that using AI-generated verbatim texts to produce assignments clearly constitutes academic misconduct (i.e., plagiarism) and updating the relevant policy accordingly should come hand-in-hand with examples of how students can use AI tools to brainstorm, develop initial ideas, and critique information sources.

An example of an AI-specific framework adopted by a university comes from Athabasca University (2020), which has developed a set of principles informing the usage of student data auto-collected by AI and adjacent learning analytics tools. These principles promote learning agency, duty of care, accuracy, and transparency, among others. Frameworks like this can support mindful use of Generative AI in classrooms and demystify these tools instead of banning them altogether.

Generative AI produced texts and images can be a perfect conversation starter, specific but not limited to such topics as intellectual property and ownership of data, textual artefacts, and innovations. The consequences of banning technologies, or introducing bans in general, can also galvanize classroom discussions. The same applies for discussions around limiting access and placing previously free technology behind paywall. Spatial inequality, device ownership, and unequal access to internet already contribute to the digital divide that disproportionally affects students located in remote areas, including indigenous learners (Prayaga et al., 2017). Banning Generative AI tools will only add to the existing inequalities, likely affecting students who may already have been (unfairly) marginalized and penalized.

While Generative AI tools present a set of both challenges and opportunities, it is important for educational bodies and institutions to remain vigilant and proactive in observing and governing the use of such tools. Frameworks governing the use of AI on campus must be driven by principles (e.g., agency, accountability, transparency) (Pechenkina, 2023) with the overarching principle being what digital rights advocates refer to as ‘data justice’ (Dencik & Sanchez-Monedero, 2022).

Educational bodies and institutions need to embrace a cultural change when it comes to Generative AI and similar technologies deemed ‘disruptive’. As history has shown, bans may not be as effective as intended; therefore, governance and strategic regulation are key to seamless integration. However, the way educational bodies and institutions conceptualize academic misconduct may need to be rethought as well, which is a much bigger and all-consuming task than writing the use and misuse of AI into policies.

Last but not least, the current narrative around academic misconduct places the onus fully on students not to engage in unethical and dishonest practices and behaviors. The bottom-line is that students are expected to cheat and therefore cannot be trusted—the policy language is clear on that. Students are warned of serious punishments in stock if they are caught, from suspension to expulsion. We argue that it is time to shift this narrative in favor of one highlighting a distributed accountability when it comes to academic misconduct—that is, leaders, administrators, educators, and students are to share the responsibility. Educational bodies and institutions should therefore allocate adequate resources to support staff and students deal effectively with Generative AI-related challenges and optimize opportunities presented by its tools.

To this end, we sum up the four paradoxes of Generative AI—i.e., (Paradox #1) Generative AI is a ‘friend’ yet a ‘foe’, (Paradox #2) Generative AI is ‘capable’ yet ‘dependent’, (Paradox #3) Generative AI is ‘accessible’ yet ‘restrictive’, and (Paradox #4) Generative AIgets even ‘popular’ when ‘banned’—along with their implications for transformative education in Table 1. Generative AI tools such as Bard, ChatGPT, and DALL-E are opening up new frontiers that will affect the way we learn, interact, and work with each other and thus requiring us to reimagine existing practices in order to be prepared for and stay relevant in the future. Our experience working with Generative AI tools suggest that it is important for users to be (i) complete and specific in prompts, which may involve (ii) laddering (e.g., clarifying with examples, structured questioning) while (iii) keeping in mind the technology’s limitation in order to scope expectations and secure the best results (lessons). The takeaways from the critical analysis herein should also offer timely advice on guidelines for educational practice and directions for educational research (Table 1). The latter—i.e., educational research—is especially important given (i) the newness of the phenomenon and (ii) the limitation of this article to conceptual and practical but not empirical insights, thereby highlighting the gap and the necessity to fill in this gap, starting with new explorations using rigorous methods that would enrich the body of knowledge on Generative AI for and in education. Therefore, taken collectively, the insights that emerge from this article should be useful for approaching Generative AI as an impetus for transformative education, ensuring that education continues to evolve in order to stay relevant and thus safeguarding the future of education, and by extension, the society of tomorrow.

CRediT author statement

Weng Marc Lim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Supervision, and Writing (Original draft, review,

and editing).

Asanka Gunasekara: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, and Writing (Original draft, review,

and editing).

Jessica Leigh Pallant: Conceptualization, Investigation, and Writing (Original draft).

Jason Ian Pallant: Conceptualization, Investigation, and Writing (Original draft).

Ekaterina Pechenkina: Conceptualization, Investigation, and Writing (Original draft).

| Takeaways | Generative AI | Definition | Transformative education | Definition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Generative AI can be defined as a technology that leverages deep learning models to generate human-like content in response to complex and varied prompts | • Transformative education can be defined as as education that is transformative in its process and product in response to gran challenges | |||||

| Lesson ↓/→ | Paradox | Positive | Negative | Key implications | Guidelines for practice | Directions for research |

| To scope expectations and secure the best results, Generative AI users can : • Be complete and specific in prompts. • Engage in laddering (e.g., clarifying with examples, structured questioning). • Keep in mind the technology's limitation and be ready to engage in further work.

|

• Paradox #1: Generative AI is a 'friend' yet a 'foe' |

• Generative AI is a 'friend' when it facilitates knowledge acquisition through timely and human- like responses • Generative AI is a 'friend' when it elevates the rigor in assessement |

• Generative AI is a 'foe' when it makes it difficult to ascertain novel versus recycled knowledge • Generative AI is a 'foe' when it threatens to make assessment redundant |

• Generative AI can accelerate learning and thus the discovery of new knowledge, though distinctions on novel and recycled knowledge need to be sorted effectively. |

• Adopt Generative AI as a tool to transform and support educational activities |

• What educational-related problems and tasks can Generative AI tools address, and how well do thay fare? |

| • Generative AI is a 'friend' when it realises its capability in offering true information. | • Generative AI is a 'foe' when it reveals its flaws in offering false information | • Generative AI can serve as a useful informant to users in education, though caution should be afforded due to its susceptibility to information disorders such as disinformation and misinformation | • Engage in fact checking and verification for information produced by Generative AI while feeding it with more information/prompts in tandem with upgrading of deep learning algorithms to allow it to detect and correct its flaws. | • How can Generative AI be trained to evaluate and make trustworthy decisions, and how can educators and students engage in counterchecking of the responses produced by such tools? | ||

| • Generative AI is a 'friend' when it realises its capability in offering true information | • Generative AI is a 'foe' when it reveals its flaws in offering false information | • Generative AI can serve as a useful informant to users in education, though caution should be exercised due to its susceptibility to information disorders such as disinformation and misinformation | • Engage in fact checking and verification for information produced by Generative AI while feeding it with more information/prompts in tandem with upgrading of deep learning algorithms to allow it to detect and correct its flaws | How can Generative AI be trained to evaluate and make trustworthy decisions, and how can educators and students also engage in counterchecking of the responses produced by such tools? | ||

| • Generative AI is a 'friend' when the information it provides is used ethically or with good intention. | Generative AI is a 'foe' when the information it provides is used unethically or with ill intention. | • Generative will inherently have an impact on academic integrity, including its improvement. | • Establish and periodically revise policies and guidellines for ethical use of Generative AI in education as and when the technology advances and develops over time. | • What is the impact of Generative AI on academic integrity policies, how can institutions encourage educators to use Generative AI while maintaining academic integrity, and what if any, methods should educators use to detect use of Generative AI in assessment submission? | ||

| • Generative AI is inherently neutral but could be trained to promote the good and mitigate the bad among users in education. | • Establish Generative AI protocols that can alert users and institutions on potential criminal and unethical engagement, as well as opportunities to improve efficiency, productivity, and performance in education. | • How can Generative AI tools be trained to detect potential criminal and unethical engagement as well as opportunities to improve proficiency, productivity and performance (i.e.. the 3 P s) in education, and how well do they fare? | ||||

| • Paradox #2: Generative AI is 'capable' yet 'dependent' | • Generative AI is 'capable' in delivering responses. | • Generative AI is 'dependent' on the quality of prompts and the type of training it receives in delivering responses. | • Generative AI education is necessary to enable its users in education to make the best use of its tools and maximize the returns from its usage. | • Establish a sustainable model for Generative AI that would promote equitable access in education. | What are the strengths and shortcomings of different categories of Generative AI tools, and how can educators and students be trained to effectively use such tools, and how do different training methods and programs fare in improving the proficiency, productivity, and performance (i.e., the 3 P s) of its users in education? | |

| • Paradox #3: Generative AI is 'accessible' yet 'restrictive' | • Generative AI is 'accessible' for people to use | • Generative AI is 'restrictive' in what and how much people are allowed to use | • Generative AI can democratize the power of education, though any conditions imposed will need to be managed equitably in order to realize its impact potential. | • Establish a sustainable model for Generative AI that would promote equitable access in education. | • What are the roles of the developers and educational institutions in creating and developing access to Generative AI tools for students, how can such access be made equitable, and how would this impact on the equity of student learning experience among different student groups along with their academic and non-academic performance in the short and long run? | |

| • Paradox 4#: Generative AI gets even more "popular' when 'banned' | • Generative AI is 'popular' for its value, even more so from the Streisand effect and psychological reactance | • Generative AI gets 'banned' for its supposed threats (e.g., academic integrity, ethics). | • Generative AI is inevitable and banning it will likely drive students to want access through heightened attention and psychological reactance, and thus, educational institutions should embrace rather than shun its use | • Establish and promote the use of Generative AI for education and its best practice instead of banning or limiting it. | • How do students perceive and respond to policies regarding Generative AI, how does banning its use impact on students accessisng such tools outside educational settings, and how can Generative AI be built into education in a meaningful way? | |

Data Availability

No data was used for the research described in this article

Notes

1 ChatGPT stands for Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (OpenAI, 2023). The phenomenon of ChatGPT popularizing Generative AI is akin to that of Facebook for social media.

2 TikTok took about nine months while Instagram took around two and a half years to achieve 100 million users (Hu, 2023).

3 On their own, chatbot and Generative AI are not new (e.g., chatbot has been used by companies to interact with visitors to websites while Generative AI has manifested through generative adversarial networks (GANs) that can create realistic images and together with variational autoencoders (VAE) ushered in the era of deepfakes), though they could be considered new at the time of writing when they are taken together (e.g.,

Bard, ChatGPT, DALL-E).

4 The idea of being transformative could be observed through the occurrence of a marked change.

5 The process of transformative education could occur in many ways, for example, leveraging new-age technology such as Generative AI across learning and teaching.

6 The product of transformative education could manifest in many ways, for instance, tech-savvy graduates who can make people and technology work together for a brighter future.

7 The grand challenges that transformative education could address are varied, which may include existential threats arising from breakthrough innovations such as Generative AI and mega-disruptions such as COVID-19.

8 While a corrigendum (O’Connor, 2023) has been issued for an article supposedly author by ChatGPT (O’Connor & ChatGPT, 2023) and the supposed author name of ChatGPT remains inconsistent (e.g., Ali & OpenAI Inc, 2023; O’Connor & ChatGPT, 2023), the point that we intend to make here is that the rapid development of Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and the way people are using it calls for urgent attention and informed action from educators, whose profession is, in essence, to provide education, or in other words, to educate, which should inarguably include innovative ways of responding to current issues.

9 The attribution of human characteristics to AI, including Generative AI, is called anthropomorphism (Lim, Kumar et al., 2022).

10 This could manifest as multi-answer/logic questions that involve the application of knowledge in new situations, analysis that draws connections among multiple ideas and forms/pieces of information including distractors, and evaluation that requires justifying a decision or stance

11 The invention of the calculator is a relevant example in history that has empowered mathematicians to focus on complex tasks and explore mathematics in greater depth by making calculations easier, more accurate, and less tedious as compared to manual calculations.

12 The queries were made on February 8, 2023.

13 Based on a Turnitin plagiarism scan on February 14, 2023. The document used for the Turnitin plagiarism scan was a paraphrased essay about ChatGPT by ChatGPT. The original essay had 685 words while the paraphrased essay had 482 words. The paraphrasing instruction—i.e., “Please paraphrase the essay below, which should be a minimum of 500 words”—was conveyed together with the original essay about ChatGPT, which was sourced from Wikipedia on February 14, 2023, to ChatGPT.

References

ABC News. (2023). Queensland to join NSW in banning access to ChatGPT in state schools. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-01-23/ queensland-to-join-nsw-in-banning-access-to/101884288.

Ali, F., & OpenAI, Inc, C. (2023). Let the devil speak for itself: Should ChatGPT be allowed or banned in hospitality and tourism schools? Journal of Global Hospitality and Tourism, 2(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5038/2771-5957.2.1.1016

Alt, D. (2017). Students’ social media engagement and fear of missing out (FoMO) in a diverse classroom. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29(2), 388–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-017-9149-x Athabasca University. (2020). Principles for ethical use of personalized student data. Available at: https://www.athabascau.ca/university-secretariat/_documents/policy/principles-for-ethical-use-personalized-student-data.pdf.

Brehm, J. W. (1989). Psychological reactance: Theory and applications. Advances in Consumer Research, 16, 72–75. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/6883/ volumes/v16/NA-16.

Center for Information Technology and Society. (2023). Why we fall for fake news. University of California Santa Barbara. Available at: https://www.cits.ucsb.edu/fake-news/why-we-fall.

Chatterjee, J., & Dethlefs, N. (2023). This new conversational AI model can be your friend, philosopher, and guide … and even your worst enemy. Pattern, 4(1), Article 100676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2022.100676

Cheddadi, S., & Bouache, M. (2021). Improving equity and access to higher education using artificial intelligence. In The 16th international Conference on computer science & education (ICCSE 2021) (pp. 18–20). August 2021 (Online).

Dencik, L., & Sanchez-Monedero, J. (2022). Data justice. Internet Policy Review, 11(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.14763/2022.1.1615

Dibble, M. (2023). Schools ban ChatGPT amid fears of artificial intelligence-assisted cheating. VOA News. Available at: https://www.voanews.com/a/schools-banchatgpt-amid-fears-of-artificial-intelligence-assisted-cheating/6949800.html.

Dowling, M., & Lucey, B. (2023). ChatGPT for (finance) research: The Bananarama conjecture. Finance Research Letters. , Article 103662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.103662

Fatemi, G., & Saito, E. (2020). Unintentional plagiarism and academic integrity: The challenges and needs of postgraduate international students in Australia. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(10), 1305–1319. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1683521

Ferraro, C., Wheeler, M. A., Pallant, J. I., Wilson, S. G., & Oldmeadow, J. (2023). Not so ‘trustless’ after all: Trust in Web3 technology and opportunities for brands. Business Horizons. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2023.01.007

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hammer, A. (2023). The rise of the machines? ChatGPT CAN pass US medical licensing exam and the bar. Experts Warn – After the AI Chatbot Received B Grade on Wharton MBA Paper. Daily Mail. Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11666429/ChatGPT-pass-United-States-Medical-Licensing-Exam-Bar-Exam.html.

Harwell, D. (2023). As states ban TikTok on government devices, evidence of harm is thin. Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/01/20/tiktok-bans-states-colleges/.

Holden, O. L., Norris, M. E., & Kuhlmeier, V. A. (2021). Academic integrity in online assessment: A research review. Frontiers in Education, 6, Article 639814. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.639814

Hu, K. (2023). ChatGPT sets record for fastest-growing user base. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpt-sets-record-fastest-growinguser-base-analyst-note-2023-02-01/.

Jaeger, C. (2023). AI tool banned in Victorian state schools. The Age. Available at: https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/ai-tool-banned-in-victorian-schoolsas-implications-examined-20230201-p5ch8h.html.

Jansen, S., & Martin, B. (2015). The Streisand effect and censorship backfire. International Journal of Communication, 9, 656–671.

Kelly, S. M. (2023). ChatGPT passes exams from law and business schools. CNN. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/01/26/tech/chatgpt-passes-exams/index.html.

Kraus, S., Breier, M., Lim, W. M., Dabi´c, M., Kumar, S., Kanbach, D., … Ferreira, J. J. (2022). Literature reviews as independent studies: Guidelines for academic practice. Review of Managerial Science, 16(8), 2577–2595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00588-8

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Lim, W. M. (2021). History, lessons, and ways forward from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Quality and Innovation, 5(2), 101–108.

Lim, W. M., Chin, M. W. C., Ee, Y. S., Fung, C. Y., Giang, C. S., Heng, K. S., … Weissmann, M. A. (2022). What is at stake in a war? A prospective evaluation of the Ukraine and Russia conflict for business and society. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 41(6), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22162

Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., Verma, S., & Chaturvedi, R. (2022). Alexa, what do we know about conversational commerce? Insights from a systematic literature review. Psychology and Marketing, 39(6), 1129–1155. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21654

Lowenthal, P., Borup, J., West, R., & Archambault, L. (2020). Thinking beyond Zoom: Using asynchronous video to maintain connection and engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 383–391. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216192/.

Lukpat, A. (2023). ChatGPT banned in New York City public schools over concerns about cheating, learning development. The Wall Street Journal. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/chatgpt-banned-in-new-york-city-public-schools-over-concerns-about-cheating-learning-development-11673024059.

Marks, A., & Al-Ali, M. (2022). Digital transformation in higher education: A framework for maturity assessment. In COVID-19 challenges to university information technology governance (pp. 61–81). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13351-0_3.

Nature. (2023). Tools such as ChatGPT threaten transparent science; here are our ground rules for their use. Nature, 613, 612. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00191-1

Nikolopoulou, K. (2021). Mobile devices and mobile learning in Greek secondary education: Policy, empirical findings and implications. In A. Marcus-Quinn, & T. Hourigan (Eds.), Handbook for online learning contexts: Digital, mobile and open: Policy and practice (pp. 67–80). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67349-9_6.

O’Connor, S. (2023). Open artificial intelligence platforms in nursing education: Tools for academic progress or abuse? Nurse Education in Practice, 66, Article 103537.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103572

O’Connor, S., & ChatGPT. (2023). Open artificial intelligence platforms in nursing education: Tools for academic progress or abuse? Nurse Education in Practice, 66, Article 103537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103537

Open Culture. (2023). Noam Chomsky on ChatGPT. Open Culture. Available at: https://www.openculture.com/2023/02/noam-chomsky-on-chatgpt.html.

OpenAI. (2023). OpenAI. Available at: https://openai.com/.

Paul, K. (2023). The new frontier in the US war on TikTok: University campuses. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/jan/20/us-tiktok-bans-university-campuses.

Pavlik, J. V. (2023). Collaborating with ChatGPT: Considering the implications of generative artificial intelligence for journalism and media education. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776958221149577

Pechenkina, K. (2023). Artificial intelligence for good? Challenges and possibilities of AI in higher education from a data justice perspective. In L. Czerniewicz, & C. Cronin (Eds.), Higher Education for good: Teaching and learning futures (#HE4Good). Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers.

Pichai, S. (2023). An important next step on our AI journey. Google. Available at: https://blog.google/technology/ai/bard-google-ai-search-updates/.

Prayaga, P., Rennie, E., Pechenkina, E., & Hunter, A. (2017). Digital literacy and other factors influencing the success of online courses in remote Indigenous communities. In J. Frawley, S. Larkin, & J. Smith (Eds.), Indigenous pathways and transitions into higher education: From policy to practice (pp. 189–210). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4062-7_12.

Rychen, D. S. E., & Salganik, L. H. E. (2003). Key competencies for a successful life and a well-functioning society. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

Sahoo, S., Kumar, S., Abedin, M. Z., Lim, W. M., & Jakhar, S. K. (2023). Deep learning applications in manufacturing operations: A review of trends and ways forward. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 36(1), 221–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-01-2022-0025

Scite. (2023). See how research has been cited. Available at: https://scite.ai/.

Stokel-Walker, C. (2022). AI bot ChatGPT writes smart essays — should professors worry? Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-04397-7

Terwiesch, C. (2023). Would Chat GPT3 get a Wharton MBA? A prediction based on its performance in the operations management. The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Available at: https://mackinstitute.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Christian-Terwiesch-Chat-GTP.pdf.

University, M. (2023). Acknowledging the use of generative artificial intelligence. Available at: https://www.monash.edu/learnhq/build-digital-capabilities/createonline/ acknowledging-the-use-of-generative-artificial-intelligence.

Yap, S. F., & Lim, W. M. (2023). A paradox theory of social media consumption and child well-being. Australasian Marketing Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/14413582221139492

Young, J. R. (2018). Should professors (a) use multiple choice tests or (b) avoid them at all costs? EdSurge. Available at: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2018-05-10-should-professors-a-use-multiple-choice-tests-or-b-avoid-them-at-all-costs.

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education–where are the educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), 1–27.

Zhai, X. (2022). ChatGPT user experience: Implications for education. Available at SSRN 4312418