Chapter 8. Thinking Critically About Moral Issues

Learning Objectives

- Understand the distinction between analytic, synthetic, and normative propositions

- Identify the three types of value proposition

- Distinguish between ‘is’ and ‘ought’ as per Hume’s guillotine

- Be able to detect the commission of the naturalistic fallacy

- Understand the justification of normative propositions according to virtue, deontological, consequentialist ethical frameworks.

New Concepts to Master

- Normative propositions or statements

- Value proposition

- Hume’s guillotine

- Naturalistic fallacy

- Virtue ethics

- Deontological ethics

- Categorical imperative

- Consequentialist ethics

- Utilitarianism.

Chapter Orientation

You’ve made it to the final chapter. You should be proud of yourself. I know for many of you, this text is far more technical and challenging than you might have expected – or that I led you to believe in Chapter 1 – but that was just so I could lure you into a false sense of security before hammering you with mind-blowing facts and the trickier mechanics of reasoning.

The bottom line is that reasoning is hard and very complex, and we are somewhat pre-programmed to do it poorly, so learning a new and more robust approach to thinking is going to feel like your brain is being stretched from several different angles. All I can promise you is that the payoff is worth it. There’s nothing better for you to learn in your early stages of university than how to think properly, how to mitigate the influence of your cognitive biases, how to avoid fallacious reasoning, and how to spot these things in the thinking and reasoning of others. And this text has covered so much more about language, perception and sensation, cognitive models, webs of belief, as well as our final topic, which is morality and ethics.

Speaking of our final topic, by now you know I’m a huge fan of Wittgenstein, so you’ll forgive me for wanting to set the tone of this last chapter with another of his quotes.

The important questions of everyday life are more often than not questions about what is good and bad, right and wrong, worthwhile or not, how we should act, etc. These are moral or ethical questions, and training in critical thinking should certainly have some positive impact on those areas of our lives.

As I said in Chapter 1 and Chapter 2, critical thinking isn’t merely about learning technical reasoning rules for its own abstract sake. I know as university students your number one priority is to get the best marks you can get and to launch your successful and fulfilling careers, but I also hope that you have some moral purpose to your pursuit of learning. Specifically, I hope that you really want to think better to improve your life, improve the decisions you make, and improve the lives of those people who are around you and depend on you. I hope that I have convinced you to really want to think better for its own sake, not just to learn enough to ace this course.

This is a type of meta- or macro-level moral consideration that’s very relevant to your motivation for committing time and energy to these critical thinking lessons. There are of course multiple motivations for you to invest this time and energy, and I think if you take time to invest some thought into the values and judgements that have led you to this place in your life, you’ll be well on your way to thinking critically about moral issues. All of our choices depend somewhat on values and are shaped by our moral outlook. It’s vital that you can think critically and impartially about these issues to maximise your success.

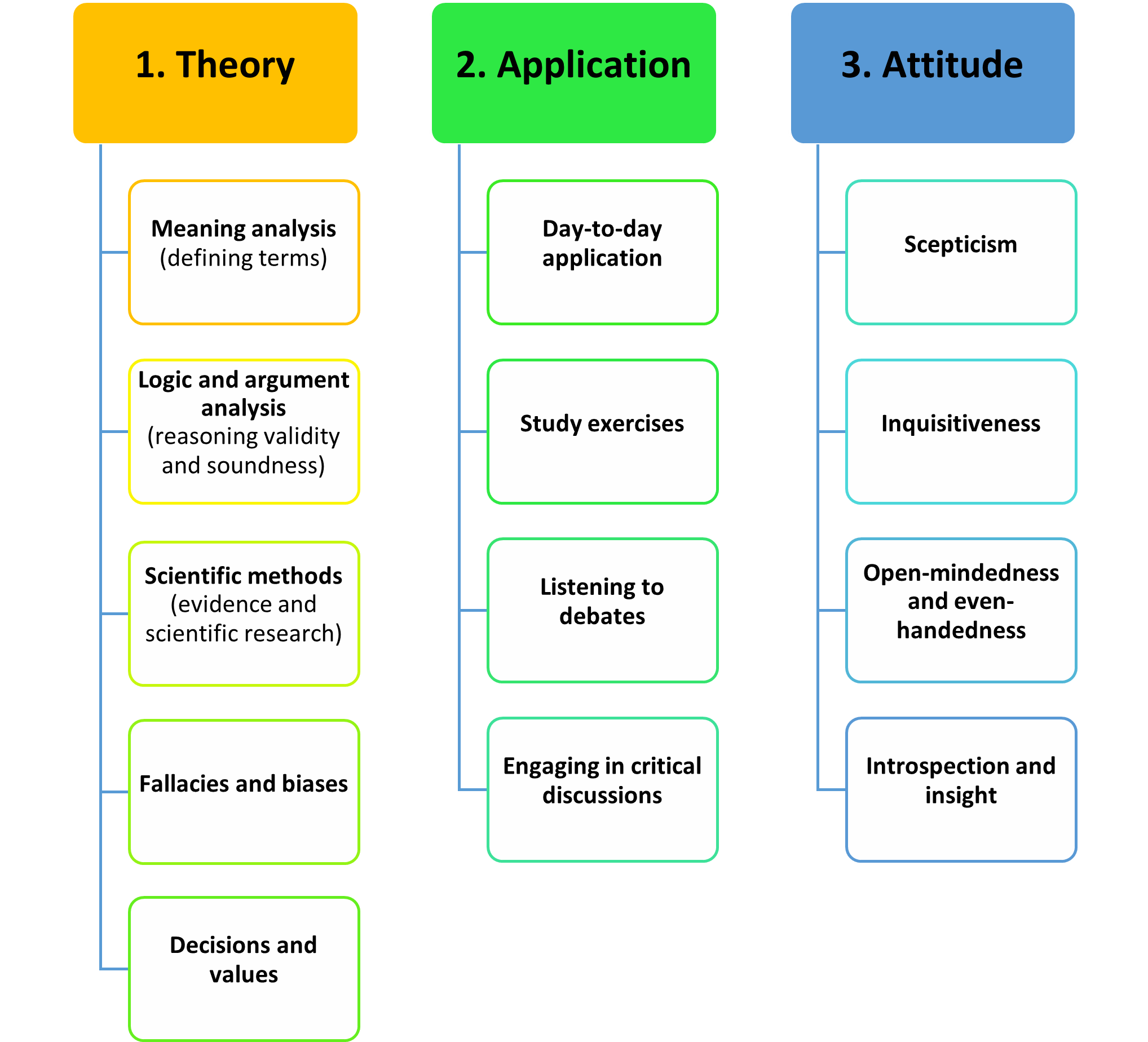

Our second chapter relied on a framework developed by Joe Lau (see Figure 2.3, which is reproduced here) in which developing our thinking was organised into steps and principles that were grouped into ‘theory’, ‘practice, and ‘attitude’. One of the five important parts of the ‘theory’ component was ‘decisions and values’, and this chapter will take what we talked about in that chapter as a launching point.

A huge chunk of our concern in this text has been on claims. People make claims all the time – each of us makes claims both to ourselves and to other people we encounter (for example, those we’re trying to persuade or sell to). Critically and safely navigating our world has a lot to do with critically and safely navigating the flood of different claims we’re bombarded with on a daily basis. However, until now, we’ve dealt with objectively verifiable propositions – that is, claims that can be shown to be either ‘true’ or ‘false’ (shown to be is the key here). This chapter fits into the larger picture by beginning to recognise that many of the claims we make and have to deal with are actually moral claims or claims about right and wrong, or good and bad. These claims can only be formulated as true/false type propositions if the morality of the claim is embedded into the proposition, such as: ‘the right thing to do is X’ or ‘It’s moral to do X’ or ‘X’ is immoral’.

Ethics and morality are too often thought of as an afterthought to critical thinking, and positioning this chapter at the end of the textbook might inadvertently give that impression. However, even if we’re not always aware of it, our thinking has far-reaching consequences. Moral considerations are never far behind our thinking. From the earliest critical thinkers, moral concerns have been a major part of all intellectual endeavours. The reason I placed this material at the end was to avoid interrupting the flow of your learning, which was staged to take you from sensation and perception to beliefs, language and propositions, to arguments, reasoning, fallacies, and biases, etc. However, theories, propositions, claims, and thinking all have distinct consequences. That is, they affect us, our lives, and the people around us. Our thinking does not occur in isolation, but directly influences our behaviour; neither does our behaviour occur in isolation, but strongly influences the people around us and the communities we create and inhabit. Therefore, moral concerns are fundamental to thinking itself.

Chapter 7 Review

The last chapter was concerned with reasoning critically. I get that this is a strange title for Chapter 7 in a text where the entire subject matter is about reasoning, but the focus of Chapter 7 was really about narrowing our focus on what makes something a reason, and what makes it a good or bad reason. Because our focus is on reasoning critically, we should pay most of our attention to areas where we have vulnerabilities or blind spots so that we can better understand them and attempt to overcome them.

Our starting point for Chapter 7 was to disentangle our concerns about pieces of reasoning (that is, arguments) that focus on issues of content versus structure. Every piece of reasoning has both content and structure. Content is what the piece of reasoning says, what is being referred to, or talked about, while the structure is the organisation or layout of the fragments of an argument. In Chapter 6, we focused quite heavily on issues relating to the form or layout of reasoning. Chapter 7 focused on the content of the reasoning, or issues with the reasons themselves. As a result, Chapter 7 was concerned with cases where reasons fail and looked at informal fallacies. Remember, formal fallacies concern the structure or layout of the argument rather than the content of the statements themselves. Since we want to better understand the quality of premises (that is to say, the usefulness and persuasiveness of reasons), we’re almost exclusively looking at informal fallacies.

Reasoning is also extensively affected by other, more general, patterns or habits in our thinking. Some of these are known as heuristics, which are mental shortcuts we have for processing information and decision-making. The types of heuristic that interest us most in this course are those that are detrimental to our ability to think clearly, critically, and creatively. These types of weakness and vulnerabilities in our thinking tare known as cognitive biases. These biases are habits and filters that create vulnerabilities or blind spots in our ability to process information, make decisions, and reason.

A good starting question is ‘What are the main ways that reasons fail?’ or ‘When are reasons not fallacious or erroneous?’ I presented three means by which reasons fail to live up to standard. Firstly, because reasons in an argument are simply insufficient to support a persuasive conclusion. This usually occurs when an argument is missing key pieces of information, or uses pieces of information that are not strong enough or are not argued well enough to truly support the inference that’s being attempted. Informal fallacies with insufficient reasons involve failures that hamstring the main four types of inductive arguments that we looked at in Chapter 6. Specifically, informal fallacies of insufficiency concern failures to provide good enough reasons (1) to justify a generalisation, (2) to justify a causal inference, (3) to justify a strong enough analogy, or (4) to justify an expectation that the future will resemble the past. Often, fallacies of insufficiency could have been overcome if additional premises (additional facts or reasons) or more detailed premises to support the inference had been provided.

It’s sometimes difficult to categorise informal fallacies as either committing the sin of insufficiency or irrelevancy. Often, a premise can seem irrelevant because the set of premises is simply insufficient to show why something is relevant. Sometimes if you look at different lists online or in different books or guides, you might see that certain informal fallacies are grouped differently to the way I have them. A fallacy that I call insufficient may be called a fallacy of irrelevancy. Whether something is insufficient or irrelevant (and bear in mind something can be both), simply depends on the surrounding argument and what other premises are being included.

The second way reasons fail to live up to standards is irrelevancy. More specifically, irrelevant reasons, or fallacies of irrelevancy, occur when someone includes, as a reason, something that has nothing whatsoever to do with the claim being made. Again, I included some prototypical examples, such as using something about the person who’s presenting the opposing claim that has nothing to do with the claim itself as a reason, which is called an ‘ad hominem attack’. Another prototypically irrelevant premise is the ‘red herring’ because it’s an intentional ploy to distract or derail the argument to avoid having to address the claims being made. Another very common sin of irrelevancy is the ‘straw man’, since it allows you to include as premises in your argument, inaccurate representations of an opposing view which can be easily defeated caricatures and distortions. These types of reasoning or premises (including things such as appeal to emotion) are simply irrelevant to our ability to justify a specific conclusion. Arguments that contain premises like these commit informal fallacies of irrelevancy.

The third and final way reasons fail to ‘cut the mustard’ is due to ambiguity. Ambiguity means something has two or more meanings. As we saw in Chapter 5, most words are somewhat ambiguous in their semantic definitions, which is why the meaning of a word is also dependent on its role in a sentence or discussion, how it’s used, and the reason it’s being used (which is to say we have to take account of syntactic and pragmatic meanings). That words have an inbuilt ambiguity is quite a useful thing to manipulate in arguments when we want to avoid having to properly deal with reasons and evidence head-on. We observed instances where the ambiguity was word-sized like the equivocation fallacy, which was using a word in two different ways. This occurs when the arguer intentionally manipulates the meaning of a specific word. Ambiguity can also arise at the phrase or sentence level, such as in the ‘fallacy of amphiboly,’ where phrases are intentionally vague or misleading. The ‘composition fallacy’ and its counterpart, the ‘division fallacy,’ incorrectly assume that properties of parts automatically apply to the whole or vice versa. For instance, the composition fallacy would claim that because something is true of a part, it must also be true of the whole. Conversely, the ‘fallacy of division’ is the claim that because something is true of the whole, it must also be true of a part. Finally, we learned about moving the goalposts, which is a very popular debating tactic that you’ll see in online and formal arguments. This renders the reasoning ambiguous because it’s never exactly clear what would be sufficient and necessary evidence or reasoning to establish a claim.

There is a natural link between fallacious or flawed reasoning and our cognitive biases. A lot of the instances where we commit erroneous reasoning or where we are persuaded by fallacious reasons have to do with these built-in vulnerabilities that we call cognitive biases. Just as with informal fallacies, there’s obviously no way to give a comprehensive list of all the cognitive biases that might exist (and there may not even be such a list out there). For this reason, I focused on giving you a sampling plate that hopefully allows you to get a sense of what a cognitive bias is and how it influences our ability to reason critically, and thus gives you the ability to then spot these operating in your or other people’s reasoning.

We’ve confronted ‘confirmation bias’ several times already because I believe it’s one of the most destructive biases that we all need to confront daily and actively combat. We also benefit from biases that are useful for boosting our self-esteem, such as the ‘self-serving bias’, the ‘optimism/pessimism bias’, and the ‘fundamental attribution bias’. Interestingly, we saw that some instances of mental illness are exacerbated by reversals in some of these cognitive biases, so it’s important to remember that not everyone has these biases operating in the same way, in the same form, or to the same degree. Important biases to be aware of when you’re trying to persuade other people include the ‘backfire effect’, which is an ironic ‘digging heels in’ type of reaction that we all suffer from after being presented with evidence and reasoning against our position. ‘In-group bias’ is an interesting one that might make sense in everyday life since it seems intuitively sensible, except that it turns out to be rather blind. Experimental evidence indicates that people only really need to be told that they’re in a group they’ve never heard of before, and is even completely meaningless or random, for them to begin behaving in a way that exhibits in-group favouritism and out-group discrimination[1]. It turns out that grouping ourselves and other people is just extraordinarily fundamental to how we view and act in the world.

A note on fallacy and bias ‘lists’. This text is about sharpening your ‘garbage thinking’ detector and helping you eradicate faulty reasoning. Part of this is about developing a sixth sense so that you instinctively feel something is off when you look at your own thinking or the thinking of others. This is your cue to look into it further and consult fallacy lists to see if there is something obvious that you can label, but you don’t need a quirky fallacy name – in most instances, it’s enough to know a reason is insufficient, irrelevant, or erroneous. The fallacy names and lists are a bit of a crutch and a useful learning tool.

I provided you with some exemplar fallacies and biases that, I thought, are useful to help you learn about what these things typically involve. Before long, and with practice, you’ll stop being convinced by crappy reasons and know the reasons things are informally fallacious (insufficient, irrelevant, and ambiguous reasons, etc.) without having to consult lists of fallacy names.

A Look at Statements – One Last Time!

Firstly, let me re-address why statements matter so much that we would discuss them in almost every chapter. Statements contain the claims that represent both what and how we and others think and communicate about the world. We package these claims as statements (as opposed to whole discussions or individual words) because our thoughts and beliefs are sentence- or statement- sized and are stored in this way (and, if you recall Chapter 3, our thoughts and beliefs are also holistically tied together in a web structure). Statements are so fundamental to the way we think and communicate that to be an expert at dissecting, evaluating, and manipulating statements is to be a world-class critical thinker.

In this chapter, we’re going to learn about a new type of statement, but before we do, let’s have a quick refresh of the kinds of statements that have concerned us so far in this text. So far, we’ve learned a lot about types of statements or propositions that are either analytic or synthetic. By definition, propositions are statements that are assertions, which can be true or false. An analytic assertion, such as ‘All squares are four-sided’ is analytic because the predicate is already contained in the definition of the subject. Specifically, the subject ‘square’ is by definition a ‘four-sided object’, so the predicate is somewhat redundant. This is why these statements are explicative – because they flesh out or explicate mere definitions (for this reason, the actual claims in these statements are usually considered trivial). However, the statement is still a proposition because it can be true or false. A synthetic statement such as ‘The final text chapter will be interesting’ is synthetic because the predicate ‘will be interesting’ isn’t part of the meaning of the subject ‘the final text chapter’. These statements are ampliative because they amplify, or go beyond, what you’d know merely from the definition of the subject (nothing about the definition of the term ‘final text chapter alone tells you it’s interesting). Yet, the statement type is a proposition because the statement could be either true or false depending on what you find interesting.

In this chapter, we’ll introduce a third type of statement or proposition called ‘value statements’. Value statements or value propositions are assertions about the value of something or its moral status[2]. That is, a value statement claims something is good or bad, worthwhile or worthless, or right or wrong. These propositions or statements are different from analytic or synthetic propositions because an entirely different approach is required to demonstrate whether they’re true or false. They’re not synthetic or empirical statements because two people can accept the truth of all the facts (empirical or synthetic) and features of a situation, and yet still disagree adamantly about whether something is right or wrong, good or bad. These statements are not quite analytic either because whether you accept the claim they assert isn’t dictated purely by your understanding of the terms and their meanings.

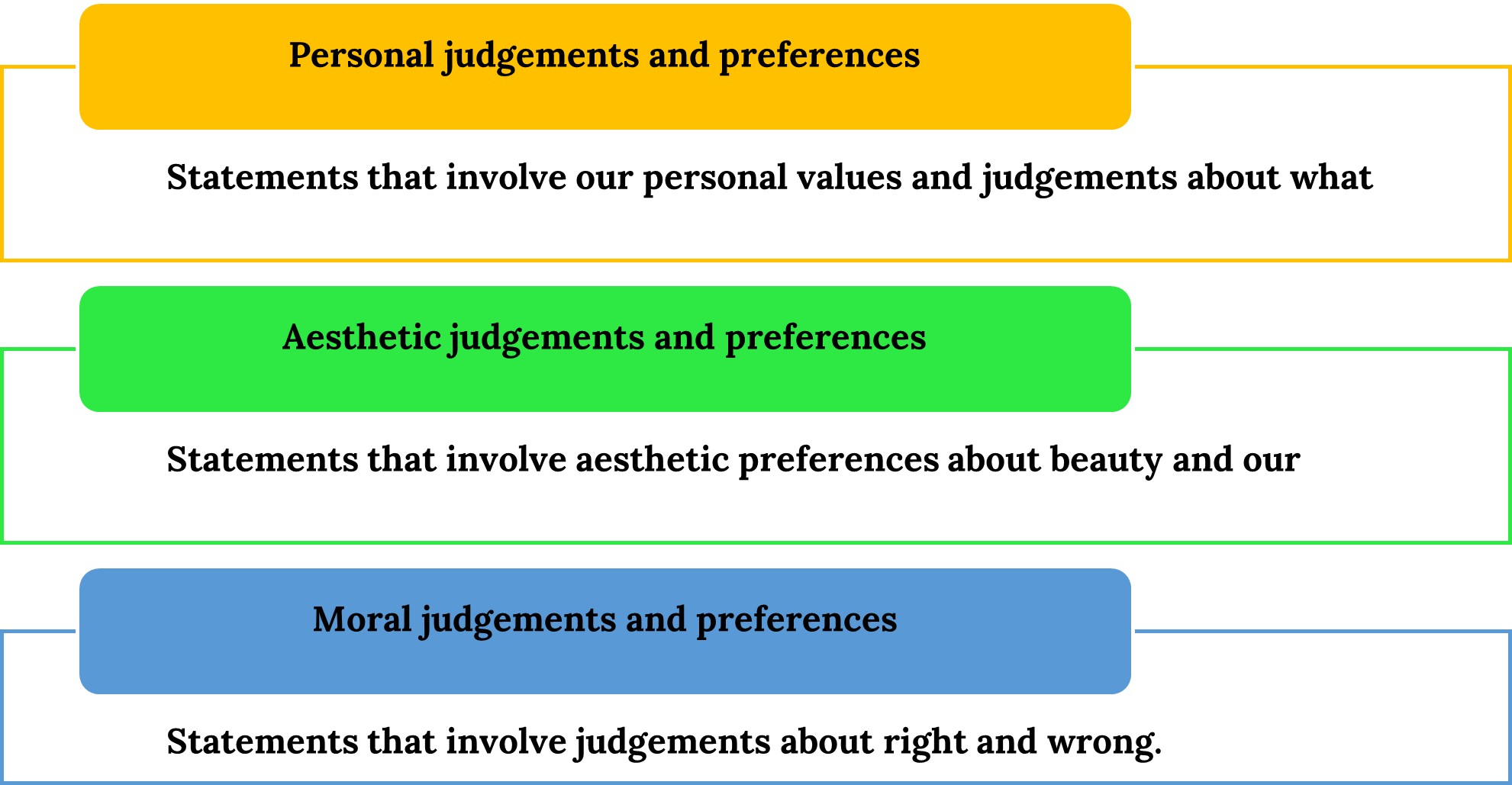

As shown in Figure 8.1., value propositions typically concern one of three things:

As you can expect in a text like this, I won’t have a lot to say about personal preferences or aesthetic judgements. The types of values that concern us most in this text are moral values, and these are often formulated and communicated via what are called normative statements or moral propositions.

Normative propositions/statements: A normative proposition is a statement that claims some moral or ethical status is true for some state of affairs (remember, all propositions are statements that claim something is true or false). The claim is usually that something is prohibited, permitted, or obligatory on the basis of moral or ethical reasons.

Normative Statements

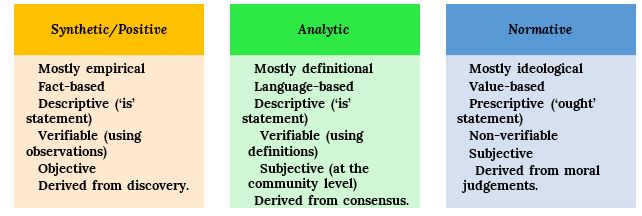

Normative statements or normative claims are a type of statement or claim that expresses values and morals about an issue. Normative statements are claims about the way the world ‘should be’ as opposed to the way the world ‘is’. Statements about the way the world ‘is’ are empirical synthetic statements. Both of these types of statements are contrasted with analytic statements, which are about the way language is and the implications of how words are defined. The distinction between descriptive (synthetic and analytic) statements and normative statements is critically important, and they shouldn’t be melded or confused, as we will discuss in more detail below.

A key difference between analytic and synthetic (empirical or positive) propositions and normative propositions is that the former are testable and verifiable: they can be shown to be true[3] or false. The test and verification might be extremely difficult but is, in principle (even if not in practice), possible. Because normative propositions represent a value judgement, they’re not objectively verifiable, but are always a subjective matter of opinion. Normative notions are largely ideological and opinion-based and depend on value judgements. Sometimes the ‘ought’ notion is referred to as prescriptive to contrast it with descriptive statements that are analytic or synthetic. Prescriptive statements are sometimes divided into two more subdivisions: imperatives (commandments about right and wrong) and value judgements (comments about the goodness or badness of something).

The following graphic (see Figure 8.2.) summarises some of the key differences in the types of statements and propositions we’ve covered in this text).

Unfortunately, the first two types of propositions are often taken as examples of the third.

The ‘Is-Ought’ Problem

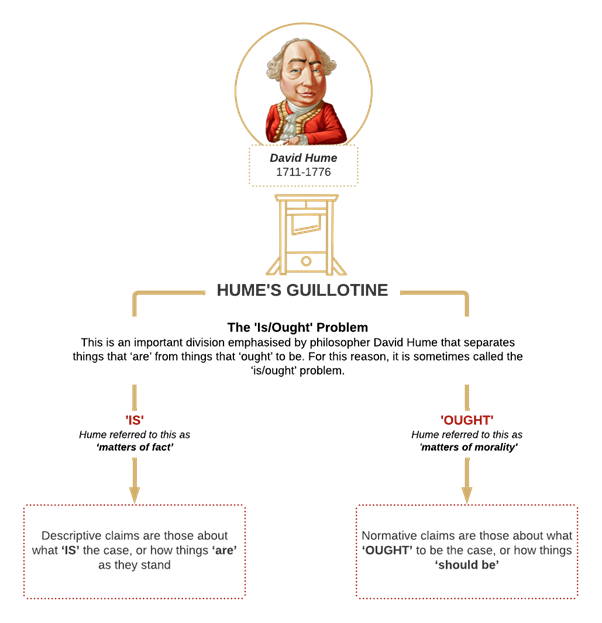

In intellectual discussions, it’s necessary to distinguish between descriptive and normative claims. Descriptive claims are those about what ‘is’ the case or how things ‘are’ as they stand (analytic and synthetic propositions are descriptive). Normative claims are those about what ‘ought’ to be the case or how things ‘should be’. There have been countless arguments in the history of science between describing the practice of science as it happens (descriptively) versus how it should be done (normatively). To confuse these two things is called the ‘is–ought problem’ or ‘is–ought fallacy’ first introduced by David Hume (yep, that jovial Scottish guy had insightful stuff to say about most things). We learned about Hume’s fork earlier (back in Figure 4.4.), in which Hume argued for a separation of ‘matters of fact’ (which involved synthetic propositions concerning things in the world) from ‘relations of ideas’ (which involve analytic propositions concerning our own concepts and their meanings). However, with Hume’s guillotine, he attempts to separate ‘matters of fact’ from ‘matters of morality’. He claims in the quote below that ‘oughts’ (moral questions and propositions) are an entirely different type of thing from ‘matters of fact’ (he calls ‘observations of human affairs’) and that trying to reason from one to the other is ‘altogether inconceivable’.

The conflation or confusion over what ‘should be the case’ on the basis of what ‘is the case’ is very common and results in committing the ‘is-ought’ fallacy. That is, ‘is’ (or descriptive) statements can’t be used to justify ‘ought’ (or normative) conclusions. According to Hume, and quite rightly, there is an unbridgeable gap between the world of facts and the world of values and morals.

Hume’s guillotine: This is an important division emphasised by philosopher David Hume that separates things that ‘are’ from things that ‘ought’ to be (see Figure 8.3.). For this reason, it’s sometimes called the ‘is/ought’ problem. This guillotine illustrates that norms (prescriptions) and facts (descriptions) should never be confused. Violating Hume’s guillotine routinely happens when people argue that because something ‘is’ the case, then it ‘ought’ to be the case. You can observe violations of this guillotine in arguments from religious people, who might claim that the way ‘God’ created things is the ‘right’ way for things to be. Another example of this is the ‘naturalistic fallacy’ committed by people who claim that because something is natural (description), it’s therefore, ‘good’ (normative). This last example is a favourite of the health food industry.

The philosophical problem here is that it isn’t clear how we go from a descriptive statement to a normative statement without additional (and very strong) premises. Hume’s guillotine is his argument that propositions that are normative can’t be confused with propositions that are positive or empirical. This is the crux of the guillotine – that we absolutely must have a clear distinction between these two types of claims to have anything like a reasonable discourse. Unfortunately, despite nearly 300 years elapsing since Hume pointed this out for us, our day-to-day thinking and discussions routinely conflate (mix) claims about what is the case and what should be the case. Earlier we met Hume’s fork, and now we meet Hume’s guillotine. If you find any of this interesting, please pursue it further. Hume is fascinating and a very accessible writer.

There is also a debate involving the value of descriptive versus normative accounts of how science should be conducted. Some historians and philosophers argue that science should be conducted just the way it is (descriptive) – after all, it has been incredibly successful (this is sometimes called the ‘no miracles’ argument). Other historians and philosophers argue that science is more often than not practised poorly and should be conducted according to specific guidelines (normative). If you’d like to learn more about the practice and history of scientific methodologies, these two perspectives on science are encapsulated nicely by influential thinkers Karl Popper (normative perspective focusing on falsification only) and Thomas Khun (descriptive perspective focusing on paradigms and inductive research programs).

Next, we’ll look at the all-too-common case of normative propositions being buried or hidden in arguments.

Undeclared/Smuggled Normative Premises

Many moral arguments or moral claims smuggle in undeclared contraband as hidden premises. Value propositions often slip under the radar or are merely implied rather than stated plainly as premises in an argument. Many of the premises that people bury, and leave assumed (unsupported assumptions), concern value statements. We naturally tend to be terrible at being aware of, and clearly articulating, the value judgements we hold that greatly influence our position on many issues. A key task in improving your own critical thinking is to be open and honest with yourself about your values so that – at least to yourself – they don’t lurk as unseen vulnerabilities in your arguments and beliefs.

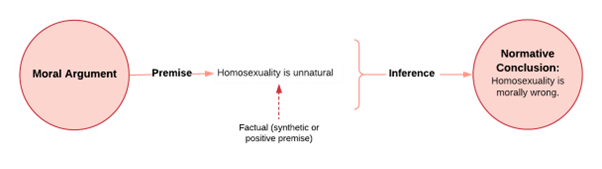

Take the following example of a proposition and argument (taken from Lau[4]):

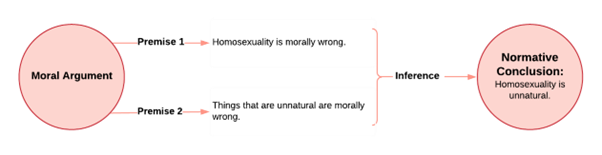

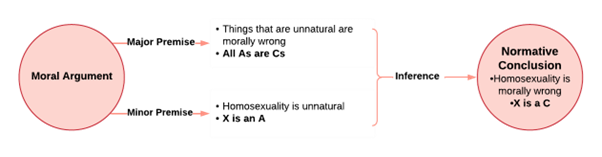

This argument is surprisingly common, and right away, we can see that the argument as it stands without any additional information commits the sin of insufficiency in its premise (we don’t always need a clever fallacy name or flash card to know an argument is flawed and obviously offensive). What is actually missing here is a hidden value proposition that’s capable of linking the premise more concretely with the conclusion. In this form, there is no real connection between the notion of unnaturalness and wrongfulness. For this reason, we know a hidden assumption is lurking here unseen. To properly appraise the argument, we need to know all the premises and reasons. The full form of the argument here is more like the following:

The missing premise was a normative proposition about the status of unnatural things. This is an unsupported assumption that takes a minute to flush out, and unfortunately, it’s surprisingly common to see this in day-to-day conversation and even formal debates. Here we see a classic case of the ‘is-ought’ fallacy, or another version of it called the ‘naturalistic fallacy’. If we can’t see the full argument, we can’t appraise it, and if we can’t properly appraise it, we have no interest in even contemplating whether the conclusion is sound.

Naturalistic fallacy: The naturalistic fallacy is an informal logical fallacy of irrelevancy that tries to argue for some moral status on the basis that it’s ‘natural’. It’s a fallacy of irrelevancy because ‘naturalness’ has nothing whatsoever to do with ‘goodness’. This fallacy is easily observed in the marketing of health products.

It’s actually much easier to appraise the argument now and see obvious flaws in the reasoning. The argument is unsound and unconvincing because the premises are blatantly false. One interesting point to be noticed, though, is that there are no formal fallacies here, in that if the premises were true, the structure has a valid deductive form. Let’s illustrate the form:

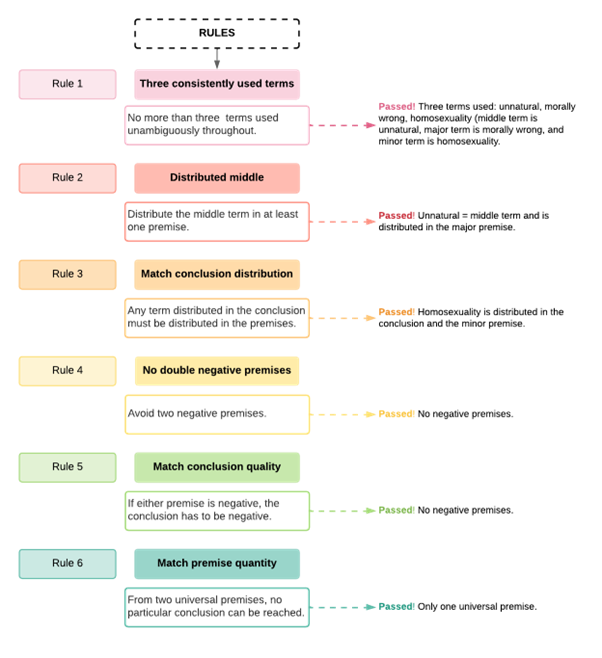

If we consult our rules of syllogisms, we find that this is a valid syllogism with three propositions and three terms all used correctly:

However, the reason we reject the conclusion and the argument is because the premises are false. Both premises have some convincing counterarguments – our lives are full of unnatural things that are not morally wrong (such as universities, critical thinking books, computers, the internet, café lattes, cricket, and Scotch whisky –I’ll stop scanning my room now). This conflation (or confusion) of what is ‘natural’ with what is ‘good’ and moral is the naturalistic fallacy and is the major problem with the argument[5].

So, this example has shown four very important points:

- Just because an argument is deductively valid doesn’t mean it isn’t flawed, harmful, and easily refuted.

- Uncovering all the premises of an argument is obviously necessary to fully appraise it.

- It’s often value judgements such as the moral status of unnatural things that are kept hidden because they’re simply assumed or not overtly considered as part of the arguments.

- Some of these hidden premises contain fallacious reasoning that isn’t always apparent when only part of the argument is presented.

Theories of Morality

Next, we turn our attention to major theories of how normative propositions should be derived. The key question here is, given normative propositions assert that actions are good or bad, what is the licence or justification for accepting their claims? In other words, given normative, or ‘should’ statements, typically proscribe or prescribe specific actions, then justification for these ‘commandments’ (pun intended) must be rooted in some theoretical accounts of why certain actions are desirable or not.

There are three main accounts of ethics that are commonly appealed to in order to provide justification for normative propositions: these accounts are based on either virtue, binding laws (deontological accounts), or on consequences.

Let’s illustrate with an example. A proposition that ‘One shouldn’t kill’ is worthwhile and persuasive because either:

- Preserving life expresses important virtues.

- It’s a fundamental law, like a law of nature – i.e., killing is simply wrong.

- The consequences of accepting this assertion are better than not accepting it.

These three accounts are called virtue ethics, deontological ethics, and consequentialist ethics.

Virtue Ethics: The Greek Philosophical Trinity

From our very first chapter, we began to meet some of the original great critical thinkers who were the ancient Greek philosophers. The most famous of these were the classical trinity of Socrates, his student Plato, and Plato’s student Aristotle. These three not only invented critical thinking, epistemology, science, and logic but also developed one of the great and enduring theories of morality and ethics.

Virtue ethics, as the name gives away, is concerned with virtues of moral character. Decisions about whether something is valuable or not, good or bad, etc., are based on what virtue it might express or represent. In this way, virtue ethics is a moral philosophy that emphasises character foremost as opposed to moral principles (as in deontological systems) or consequences (as in consequentialist systems such as utilitarian accounts). Therefore, in grappling with a normative proposition, the perspective of virtue ethics would guide us to accept those propositions that are consistent with virtuous traits. For example, someone adhering to a virtue account of ethics might accept the proposition ‘Be kind to your neighbours’ and reject the proposition ‘Do whatever it takes to get ahead’ because of the types of character traits each expresses or represents.

Central to virtue ethics is the insight that not only does our character direct our behaviour, but our behaviour in turn creates and shapes our character. Therefore, one of life’s central purposes is to sculpt our own character through actions that represent the types of attributes we would like our character to reflect. An example will help here. Determining whether I should put my litter in a rubbish bin rather than throw it out the window is not so much about littering being wrong due to some rule or law or even about the consequences of littering, but is all about who I think I am and who I want to be. Behaviours are right or wrong on the basis of what character they reflect and whether this character is virtuous. Ultimately, how I should behave is a matter of what type of person I want to be.

The classical Greeks argued persuasively that living a virtuous life is truly the ‘good life’ or achieves eudaemonia, which is just a fancy word for a state of happiness, wellbeing, or flourishing. According to these thinkers, a good life was one lived virtuously, and this would yield more satisfaction and happiness than pursuing things like pleasure, wealth, and power. Repeated reference is made in Plato’s dialogues that the morally good person is at peace and enjoys a host of psychological benefits, but these are seen as mere fortuitous payoffs to virtue, not the reason to be virtuous.

Of course, one is then entitled to wonder what virtues count as virtuous and who gets to decide. Obviously, in a simplistic sense, each person gets to decide for themselves about what counts as virtue to them, but, like everything in life, there is also some considerable influence by the context a person is in and their social and cultural environment. Certain traits, like ruthless ambition, have been considered virtuous at specific times and places, but less so in our own culture. As with all the moral theories we will encounter in this chapter, virtue ethics raises almost as many questions as it answers.

The risk of a purely virtue-based account of morality is that actions are not appraised in their own right, nor are their consequences considered. Maybe we’re more cynical in modern Western cultures or in this day and age, but most people would find this uncoupling of the morality of actions from their consequences rather unpalatable. The Enlightenment period (1700s) saw the ascendancy of utilitarian and deontological accounts of morality, after which virtue ethics became less influential in Western philosophy.

Deontological Ethics: Revisiting Kant

The next two moral theories we encounter completely ignore the individual character and focus on the intent or the actions themselves. Deontology (from the Greek meaning ‘study of obligation’) considers actions in their own right, without reference to the person committing the action or their consequences. On this account, performing the right actions and fulfilling one’s duty is more important than the consequences.

Immanuel Kant is perhaps the most persuasive exponent of deontological ethics. He argued that people must act from duty without fear of, or favour for, consequences. For this reason, what is good, is good without qualification. Kant had a solid example of this in the ‘will’ itself. A good will, he claimed, is good without qualification, and this consideration has profound influences even in today’s dominant Western legal systems (for example, in the principle of ‘mens rea’ or the intention to commit a crime). We make accommodations for the intentions or will behind actions, regardless of the actions’ consequences. Kant argues that consequences are less relevant and often out of the actor’s control anyway. What matters is the will itself and the intention to do one’s duty and perform the proper actions.

This seems to simply reassert our original question, which was, ‘How do we know the right or wrong way to act?’. But Kant has a revolutionising answer to this. His principle is that we should only act according to that maxim ‘by which we would also will that the same action becomes a universal law’. In everyday terms, this means that you should never perform an action that you wouldn’t want other people to be allowed to perform. Therefore, if you behave a certain way, you should ask yourself if you’d like for that particular action to become a universal binding law in the same sense as the laws of physics, so that everyone acts the same way. For example, if you steal from others, then you must agree that it’s okay for them to steal from you. If you don’t think this would be a good idea, you shouldn’t perform that action. He also puts this another way and argues that ‘Every rational being must so act as if he were, through this maxim, always a legislating member in a universal kingdom of ends’. He is arguing for a ‘no excuses’ type of morality here. If you want to lie about something and yet, you couldn’t accept that lying become a universal law that would bind everyone to act that way all the time, then that’s how you know lying is wrong.

This principle of Kant’s is called his categorical imperative. Another important part of the categorical imperative – and what, I think, is the best example of the maxim – is to ‘act so as to always treat humans, whether ourselves or others, never simply as a means, but always as an end’. This is a self-evident example of the principle that we should never act in a way that we couldn’t desire to become a binding universal law. We could never desire that it be a universal binding law that people are used as mere tools rather than be ‘ends in themselves’ since that would mean we ourselves are mere tools to be likewise used by others.

Categorical imperative: A categorical imperative is a moral rule (i.e., imperative) that unconditionally applies as an obligation to all people in all situations (i.e., categorically applied, not conditionally applied). The most famous of these is the ‘universalizability principle,’ which stipulates that it is only moral for a person to perform actions that they would be willing to enforce as a universal law binding all people at all times. If a person wouldn’t wish their behaviour to be copied by all other people in all other scenarios, then it’s immoral.

It’s a little harder to find everyday examples of this, but they’re not impossible to think of. Some examples include a belief that all humans have dignity and moral value and many of us hold this as a morally correct attitude, irrespective of who is championing the attitude, or what the consequences of it might be. Many people hold it as a moral truism that everyone, regardless of their gender identity, sexuality, age, race, or creed, should be treated equally under the law. Although many people holding to this view often regard it as irrelevant if this principle leads to somewhat unpalatable outcomes (such as women being enrolled in war drafts alongside men). On the other hand, if outcomes like this cause you to waver in your commitment to a radical principle of equality, then maybe you’re more of a consequentialist in your moral thinking.

Consequentialist Ethics: Meeting Bentham and Mill

The aptly named consequentialism judges moral actions based on their outcomes, irrespective of the virtue of the person or any duties or motives. In this analysis, normally immoral actions like lying or stealing could actually come out looking squeaky clean, so long as the consequences of performing them provide a greater amount of good than not performing the action. Therefore, a moral action is anything that will produce whatever is considered a ‘good’ outcome. In determining what is ‘good’, different consequentialist theories tout different end goals, including things such as pleasure, the absence of pain, satisfying one’s preferences, or a more general good (for a wider community). One influential consequentialist account is called hedonism, and this focuses on maximising human pleasure. However, the most famous version of consequentialist ethics is called utilitarianism and was devised by Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and his student, J. S. Mill (1806–1873). According to Bentham, ‘utility’ means something like ‘human welfare’. He provided some examples, such as ‘benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness’ or the prevention of ‘mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness’. According to utilitarians, morally right actions were those that produced the greatest happiness or welfare for the greatest number of people. In contrast to virtue ethics or deontological theories of ethics, consequentialist ethics seem intuitively easier to digest. Many of us naturally think that an important role for moral considerations is to make the world a better place, and therefore, consequentialist theories of morality seem to make a lot of sense. However, pushing this too far can also seem counterintuitive, as it forces us to forsake any notion of an action having moral status in its own right.

Utilitarianism: Utilitarianism is the perspective on morality that favours utility or practicality. In other words, what is right is what produces the most good for the greatest number of people. This perspective argues that morality should be about producing good outcomes, and actions are judged as moral or not on the basis of their capacity to produce desired outcomes.

In further contrast to virtue or deontological theories of morality, consequentialist accounts see morality as more dimensional rather than having discrete binary positions of good or bad, or right or wrong. Because consequentialist theories regard the goodness of an action as a product of how much ‘good’ or ‘utility’ they produce, this opens up the possibility of something being more or less good, or things having greater or lesser utility. And in that way, certain actions can be rank ordered on the basis of how much utility they have for producing good outcomes. For virtue or deontological theories, the moral status of an action is much more black and white, kind of like an on/off switch, in that it’s either moral or it isn’t – there is no more or less moral.

A major drawback of consequentialist accounts is that you never know for certain whether an action is moral until after the fact, when the results are in and the consequences can be calculated. This means that at the time of behaving, we’re always only making educated guesses about potential utility, without ever really knowing what the consequences will actually be. One only needs to spend five minutes studying history to realise that often the consequences of human actions are wildly unpredictable. Another major problem with this perspective is that the concerns of minority communities are often ignored in the bean-counting process of calculating the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Consequentialist theories also tend to ignore intention, and yet we know from our daily lives that someone’s intention always matters when judging the morality of an action (it’s the difference between murder and manslaughter in our legal system). Finally, consequentialist accounts can be used to justify seemingly horrific actions if they turn out to have positive long-term benefits (like murdering half of humanity in order to stave off global warming and save us all).

Final Word on Normative Propositions

As we know, propositions are assertions about something that can be true or false. The major problem that has motivated us in this chapter is to work out what is the warrant or justification for accepting a normative proposition as true. Determining the truth of analytic and synthetic propositions is much more straightforward, since they more objectively involve either definitions or facts and evidence. But since normative propositions are subjective and ideological, they deal with values that are personal and must be argued for at the level of moral principles and theory.

The three main theories that have been proposed as justification for normative propositions concern either qualities of:

- (1) the actor (virtue theories)

- (2) the action (deontological or duty theories)

- (3) the consequences or outcomes (utilitarian theories).

As usual, for theories that have stood the test of centuries of scrutiny, each has strengths and weaknesses. In their own way, each pretends to answer the key question about the rational justification for normative propositions, while actually deferring our confusion to another issue. What I mean is that they attempt to provide rational justification for normative propositions, but raise as many questions as they answer. For example, virtue theories claim that what is moral is whatever a virtuous person does, so this appears to answer the primary question, but in reality, palms our confusion off onto another, just as complicated issue. Specifically, ‘independently of someone’s behaviour, how is it then that we would know someone is virtuous?’. Similar concerns haunt deontological accounts, which have the appearance of answering the primary question, yet raise the obvious question that ‘independently of an action’s consequences, how is it that we would know what the correct moral duty is in any given circumstance?’. Kant’s categorical imperative does solve this to some extent, but it’s difficult to apply, and is purely hypothetical. Currently, consequentialist accounts are more universally favoured, as most people today view the moral status of an action as being a product of the consequences of that action (we don’t typically hold a killer morally accountable when they’re stopping a violent sociopath from doing harm). However, as we saw, consequentialist accounts presume too much is known about the future and about the effects of our actions. Even more confusing is that some complicated calculus is required to judge an action properly, since most of our behaviours have almost innumerable positive and negative effects. Therefore, consequentialist theories leave us back at square one. Since we can’t really know the consequences of an action before committing it and seeing the results, we remain exactly where we started, groping for some rational justification for normative propositions.

In my opinion, none of the theories are sufficient to account for all possible cases of moral behaviour, and as usual, our day-to-day moral decision-making borrows from each of them. If we introspect enough about our own moral code, we’ll likely discover that we hold a blend of moral positions on the basis of a variety of justifications (virtue, deontological, or utilitarian), and that this may even vary according to the context. For example, most people who might consider themselves to be purely consequentialist would still consider behaviours like cannibalism or necrophilia immoral even if no one ever knew about or was harmed by it in any way. Likewise, people who would claim to be purely deontologist would likely consider lying to save someone’s life as a moral action even though on a purely deontological account, lying might be categorically wrong.

The key to becoming a good critical thinker about morality is to be open and aware of the principles that guide your personal moral compass, learn about the different theoretical justifications for moral actions, and be flexible in your thinking so that you can accommodate new situations and contingencies.

Additional Resources

Of course, I don’t agree with all the perspectives and ideas expressed in these videos, but I’m sharing them to stimulate your thinking and provide a range of perspectives on the issues presented so that you can practice dealing with issues more critically.

Of course, I don’t agree with all the perspectives and ideas expressed in these videos, but I’m sharing them to stimulate your thinking and provide a range of perspectives on the issues presented so that you can practice dealing with issues more critically.

By scanning the QR code below or going to this YouTube channel, you can access a playlist of videos on critical thinking. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

Chapter 8 Review

Since there is no Chapter 9 in which to place the Chapter 8 review, this will have to hang out here on its own. Like most of this book, Chapter 8 is concerned with propositions and how we go about deciding whether to accept them or not. However, we’re interested here in a new type of proposition: the normative proposition. The location of our material on normative propositions at the end of this text in no way reflects a lack of importance. These types of propositions are often the most common and important ones we deal with in daily life.

In contrast to analytic and synthetic propositions, normative statements assert a value judgement or claim about what or how things ought to be. In this way, normative propositions are prescriptive rather than descriptive, which is a key difference between them and analytic or synthetic propositions. In fact, analytic and synthetic propositions are sometimes grouped together under the name ‘descriptive propositions’, and thereby, contrasted with prescriptive or normative propositions. Normative propositions are prescriptive because they state or prescribe how things should be, not merely describe the way things actually are.

As with all proposition types, our main headache is always to find a way to justify accepting or rejecting them. Unfortunately, we can’t use any of the frameworks suitable for judging analytic or synthetic propositions because decisions about right and wrong simply have very little to do with teasing out the meaning of our words (as with analytic propositions) or observable facts about the world (as with synthetic propositions). Despite this, it’s common for people to use descriptions about facts to justify claims about right and wrong, and it was this tendency that Hume tried to warn us against with his famous guillotine. In what has been called the ‘is-ought problem’, Hume showed that there is no rational way to move from descriptive propositions to normative ones – certainly not without smuggling in hidden premises. We’ve previously discussed the importance of being constantly vigilant against hidden assumptions.

Next, Chapter 8 turned to some influential theories of morality and ethics in the hopes that we might discover a framework to guide us in dealing with normative propositions. Virtue ethics – championed by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle – is a perspective that emphasises the type of character that is expressed or represented by a given normative proposition. In this way, we’re guided to accept or reject these normative claims on the basis of the virtues they might embody. In contrast, deontological accounts – championed by Kant –favour rules and laws and a person’s moral duty as the critical deciding factor. According to deontological ethics, certain actions themselves are inherently wrong or right, and this can be determined on the basis of careful reasoning. In contrast, consequential theories such as utilitarianism – championed by Mill and Bentham – prioritise results. For these thinkers, normative propositions should be judged not by the virtues they embody or according to rationally derived rules, but simply by the outcomes of accepting or rejecting them.

Like any influential theory, all of these frameworks have great strengths and debilitating weaknesses. In diving into each, we discovered that they all solve a major headache when it comes to thinking about morality, but invariably open up as many questions as they answer. Specifically, virtue ethics gives us a principled way to deal with normative propositions that can flexibly accommodate individual differences in people, contexts, and sociocultural backgrounds. Virtue ethics even motivates us to act consciously and consistently with our values, which is important for living a happy and fulfilled life. However, questions remain as to how the identification of virtues should be carried out, and ultimately, the application of this approach might be too vague and flexible. On this account, someone could argue for a perverted form of morality behind Hitler’s murderous rampage during the Holocaust, as he was acting consistently with his virtues. Deontological accounts eliminate any flexibility by claiming morality can only be grounded in fixed rules to which everyone is duty-bound. When such rules can be discovered, this approach is simple and easy to apply. However, the question of where these rules should come from leaves us almost back at square one. Consequentialism takes a lot of this uncertainty away by weighing the results of actions. In this way, it opens up a whole new area of uncertainty regarding how we could begin to know and calculate the consequences of any given action, and how we handle the fact that any given action has almost unlimited positive and negative consequences.

Despite these limitations, these theories provide plenty of useful pointers that can guide us when confronting normative propositions. In reality, we likely draw on all three simultaneously and emphasise different approaches in specific situations. As with many of the things we’re interested in when it comes to critical thinking, self-awareness and flexibility are essential traits in navigating normative propositions.

- AlleyDog.com. (n.d.). Minimal group paradigm. Retrieved May 13, 2023, from https://www.alleydog.com/glossary/definition.php?term=Minimal+Group+Paradigm ↵

- When I use the phrase ‘value proposition’, I’m not referring to business jargon about unique selling points, etc., but about declarative statements that propose or assert some value or moral attribute or state of affairs. ↵

- Although because of difficulties with unavoidable fallacious reasoning such as ‘affirming the consequent’ and the issue with induction, we now know that synthetic propositions can never be conclusively shown to be true. That is, they can never be proved beyond any doubt. ↵

- Lau, J. Y. F. (2011.). An introduction to critical thinking and creativity: Think more, think better. John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- introduced by British philosopher G. E. Moore in his 1903 book, Principia ethica. See this Wikipedia page for more information. ↵