Chapter 7. Reasoning Critically

Learning Objectives

- Understand the distinction between argument structure and content

- Understand the distinction between formal and informal fallacies

- Be able to identify reasons that are insufficient, irrelevant, and/or ambiguous

- Identify by name and feature various informal fallacies

- Identify by name and feature various types of cognitive biases.

New Concepts to Master

- Argument content versus structure

- Informal fallacies

- Insufficient reasons

- Irrelevant reasons

- Ambiguous reasons

- Cognitive bias.

Chapter Orientation

This is our second last chapter, and by now, you’ve climbed the enormous mountain of very technical argument dissection and analysis. However, I’m sure you’re all still catching your breath from last chapter’s content. So this chapter will follow on closely from that one, while being much less intense (no symbols this chapter!), and nowhere near as technical.

Similar to other chapters, this chapter’s content should be a whole text in itself, so we’ll barely skim the surface. The additional learning resources at the end of the chapter will help fill in more details for you. Reasoning means numerous different things to numerous different people (and yes, I get that I say this nearly every chapter), so it’s important that we’re all clear early on about what exactly I’m talking about when I refer to reasoning. In this chapter, we’re dealing with what it means for something to count as a good reason for something else. We’ve learned so far in this text that the best way to identify and appraise reasons and reasoning is to dissect what is being communicated into parts of an argument (every claim about the world rests on an argument). This makes the offered reasons much clearer, as they stand out on their own as premises. It also makes the reasoning steps much clearer, since it’s easier to see how these reasons are intended to justify an inferential leap. We’ve also seen many times already that the connective tissue between what is offered as a reason and the claim itself is called an inference. This connective tissue must be scrutinised in its own right (hence the long-winded-ness of the last chapter).

We know arguments have content and structure, and both are important. Content refers to what an argument is about – basically, what is being talked about. Structure is its organisation, and is independent of what is being talked about. We saw last chapter that one of the easiest ways to appraise argument structures is to remove all reference to content and translate everything into abstract symbols. For this chapter, we can’t do that because we’re dealing with the content itself (which is good news for you as it means there is no more ps and qs). Here we’re concerned with what is actually being offered as reasons and how these impact reasoning and inferences. The basic theme of this chapter is that to reason properly – which is to say, to reason critically – we need to avoid informal reasoning fallacies and reduce the influence of cognitive biases.

Previously we spent a great deal of time looking at the structure (formal rules and fallacies) of this rational set-up, but in this chapter, we’ll look more closely at the reasons themselves and when they go awry – focusing, therefore, on informal logical fallacies. We introduced informal fallacies in Chapter 2, so you can consult the definition in the orange Technical Terms box there if necessary. Briefly, informal fallacies concern the content of the premises, while formal fallacies are more concerned with what types of sentences are being used to justify a conclusion, regardless of what the content of the reasons are. That is, what they say, and how this serves to justify the conclusion. For informal fallacies, it’s more a matter of how the premises are inadequate as reasons. Contrary to popular belief, informal fallacies concern both deductive and inductive arguments, though a deductive argument containing an informal fallacy may still be formally valid, the informal fallacy makes it unpersuasive. In this chapter, we won’t focus on argument structures (inductive or deductive), but rather the content of the reasons, and the extent that they’re reasonable and persuasive.

In the preceding chapter, when looking at arguments and their structure, the actual reasons or content of the premises was less important. This chapter will inspect reasoning from the other angle and examine what counts as a reason and what doesn’t. We’ll also look at another major topic in reasoning that we haven’t given sufficient attention to so far: cognitive biases. These processing shortcuts generally exert an enormous – and largely unjustified – influence on our reasoning.

Chapter 6 Review

The focus of the last chapter was on formal descriptions of arguments, both inductive and deductive. First up, we looked at categorical syllogisms, which are called categorical because the proposition that they’re built on involves categories of things and describe category properties or memberships. There are four types of categorical propositions, which vary in the quantity or amount of things in the category they refer to: either all (universal) or part (particular) of the category. The types of categorical propositions also vary according to their quality, meaning they either affirm that a characteristic belongs to a category or deny it. As a result, these four types of propositions make different claims about how characteristics are distributed across terms or categories. ‘Term’ is just a technical word meaning the reference name for the categories of a proposition. Therefore, a term is just the name of a group of things that a categorical syllogism refers to. Nearly all propositions have two terms: a subject term and a predicate term. The subject of a proposition is the thing that’s being talked about, whereas the predicate is the description being given to the subject. For example, in the proposition ‘All whales are mammals’, the subject term is ‘whales’ and the predicate term is ‘mammals’. Next, we have to determine whether those terms are distributed to define the proposition type. Using the table I provided last chapter, we know it’s a universal affirmative: it has a distributed subject and an undistributed predicate – a type A proposition. This means the proposition is referring to ‘all’ whales, so the claim is saying something about this whole category, which is why it’s distributed across all members of that subject term. In contrast, the proposition isn’t referring to ‘all’ mammals, and so the claim isn’t about all members of this category. This is why it’s undistributed across the predicate term: because there are lots of mammals that aren’t being referred to.

The distribution factor may seem overly technical, but it’s a really important characteristic to consider when it comes to evaluating the validity of categorical syllogisms. Dissecting syllogisms into their constituent propositions, understanding the types and characteristics of each different proposition, and then further dissecting propositions into the subject and predicate terms and the distribution factor, are the main tasks in appraising categorical syllogisms. The final piece of the puzzle is to understand the role of terms within the whole syllogism, rather than inside propositions. One term is called the minor term, and this often has the role of being the subject term in the conclusion proposition. Another term is called the major term, and this often has the role of being the predicate term in the conclusion proposition. The third term in a syllogism, which isn’t used in the conclusion, is called the middle term.

Once you understand this, we can move on to applying specific rules that govern the validity of syllogisms. We have six rules that need to be satisfied to ensure we have a valid syllogism:

- A syllogism can only have three terms (major, middle, and minor) that are used consistently across the three propositions.

- The middle term must be distributed in at least one of the premises. Therefore, whatever the middle term is, it must refer to every member of its category for at least one of the premises.

- Any term that’s used to refer to all members of a category (i.e. distributed) in the conclusion must also perform that role in least one of the premises.

- Both premises can’t be negative – one must be an affirmative type.

- We can’t have two negative premises, so if either premise is negative (because we can have one negative premise), the conclusion must also be negative.

- From two universal premises, we can’t reach any particular conclusion. For this reason, if we have two universal premises, the conclusion has to follow suit.

Next, we turned our attention to conditional or hypothetical arguments, and we looked at two of the most common types: the modus ponens and the modus tollens. Modus ponens is ‘the way of agreeing’, whereas modus tollens is ‘the way of denying’. For both types of conditional or hypothetical arguments, the first premise can be exactly the same – it’s when we reach the second premise that they differ. For example, if we have a conditional proposition that ‘If you have the PIN code then you can access my phone’, for the method of agreement, the second premise is simply the affirmation that you do have the PIN code. If we accept both of these premises, we’re forced to accept the conclusion that you can get into my phone. This is a valid deductive argument. For the modus tollens argument, the second premise, ‘That you couldn’t get into my phone’, reveals to us that you actually don’t have the PIN code. These two premises guarantee a valid conclusion.

The modus ponens and modus tollens are valid uses of conditional arguments, and we also saw that each has a fallacious version. Modus ponens is said to validly affirm the antecedent because the second premise does exactly this. The fallacious version is to affirm the consequent. Modus tollens is said to validly deny the consequent since this is what the second premise states. Conversely, its fallacious version denies the antecedent. When we fallaciously affirm the consequent, we’re concluding backwards, knowing that ‘If p then q…’, and having observed ‘q’, we conclude ‘…therefore, p’ is the case. This is an unjustified conclusion because it’s not forced to be true by the premises alone. We simply don’t know what’s going to be the case if ‘q’ holds. All we know is that ‘q’ will follow if ‘p’ is the case. We know nothing about what happens when ‘q’ is the case. Likewise, when we fallaciously deny the antecedent, we’re concluding forwards from knowing ‘If p then q…’, and having not observed ‘p’, to concluding ‘…therefore, q’ won’t be the case. This is also unjustified because we simply don’t know what’s going to be the case if there’s no ‘p’, and we don’t know what the other conditions or causes are that might produce ‘q’.

Armed with this logical understanding, we can start to understand a bit more about scientific reasoning. Science uses modus ponens to derive observable hypotheses from theoretical claims. If I have a theoretical claim, then this serves as the ‘p’ in the ‘If p then q’ conditional proposition. The ‘q’ is the observable hypothesis that we derive from it. If my theoretical claim is that mobile phone towers cause cancer (the ‘p’), a deducible observational consequence of this (the ‘q’), could be that those people living near mobile phone towers will have increased rates of cancer, compared to an identical sample living away from mobile phone towers. When we do our research study, we might find that our sample living near the mobile phone towers don’t actually have increased rates of cancer. Therefore, we can conclude, using modus tollens, that given ‘not q’ (no evidence to support our hypothesis), ‘therefore, not P’, and on this basis, we can conclusively falsify the theoretical principle.

When science doesn’t use valid deductive arguments, and we observe confirming evidence from a research study. this is the instance of affirming the consequent fallacy. In this case, we observe q and find more cancer among our sample living near the mobile phone towers (since q is the observational evidence for our hypothesis), and therefore, conclude backwards to ‘therefore p’, which is fallacious. Rather, what we have to do is convert the argument into an inductive argument, and see this new experimental evidence as forming one premise in a potentially convincing – though uncertain – inductive argument.

We then explored inductive arguments because as you can see, they play a huge role in everyday life, as well as in science. Inductive arguments are much weaker, and can’t achieve the airtight certainty of deduction, but this doesn’t mean they’re useless – we couldn’t really get by without them. We run into trouble when we hold on to inductive conclusions as though they’re decisive or proven. We learned about four types of inductive arguments, starting with enumerative inductions, in which a series of observed instances are used to support a conclusion about either a future case (as in predictive induction) or about a whole group or class of things (as in generalisations). Another type of induction uses analogy, such as when two objects are similar in several important respects – from this we can infer additional information to help us understand another analogous object. Finally, inferences to cause and effect, which is probably the most difficult to establish. Causality is one of the most powerful conceptual tools we have at our disposal, since understanding the causes of things allows us the power to predict, explain, and control them. However, causality is one of the most difficult things to establish in science and in everyday life. There are a series of conditions we need to establish to be confident that we have the correct causal inference, and these must be established as premises in a causal argument. More on these conditions later in this chapter.

Reasons and Reasoning

The fundamental starting point for most of our chapters is to ask a deceptively simple question such as ‘What is reasoning?’, only to quickly find ourselves struggling to stay afloat in some deep and uncertain waters. This chapter will be no different, so I hope you brought your floaties. Almost anything can be a reason, but what counts as a compelling or persuasive reason is a whole different kettle of fish. As you can tell, there is some subjectivity to be accommodated here. Something that’s persuasive to one person might not be persuasive to another, but here we’ll discuss general principles around when and how reasons perform their job properly. We’ll come across a series of ‘reasons’ that are erroneous and shouldn’t be persuasive to anyone.

The stage of analysis we’re concerned with in this chapter relates more to the content and legitimacy of the reasons, and less to the connective tissue of how reasons connect with claims and conclusions. Therefore, once you’ve analysed an argument into its constituent components, we’ll be focusing on the premises or reasons offered in the argument.

As with many things, it’s much easier to explain what makes for a good reason by outlining what makes reasons bad. We can start out with some basic principles and use these to demarcate what makes a reason admissible or (informally) fallacious in the context of an argument. A reason should be sufficient, relevant, and unambiguous. Using these criteria, we can look closely at instances where reasons fail to measure up. When reasons are insufficient, irrelevant, or ambiguous, we’re dealing with fallacious or erroneous reasoning. Let’s be clear about informal fallacies first before going into details about what makes them fallacious – in other words, what makes them insufficient, irrelevant, or ambiguous.

Informal Fallacies

As we know, a fallacy is a defect in reasoning. That defect can concern either the organisation or form of the propositions or argument or their content (what the propositions say). To reiterate what I said earlier, while the form of the argument is always relevant, informal fallacies are mistakes in reasoning that arise from mishandling the content of propositions that serve as reasons or premises. This contrasts with the formal fallacies we confronted last chapter when we were concerned with ‘types’ of statements – how they connect to each other, and to the conclusion. Informal fallacies are mistakes in reasoning that occur because the premise offered is insufficient, irrelevant, or ambiguous in its task of supporting the conclusion. In this way, informal fallacies can’t be identified without understanding the content they refer to.

It might be surprising to learn how commonly these fallacies are committed and relied upon in everyday discussions, as well as in formal settings. For a range of psychological reasons, informally fallacious reasons can often be useful and persuasive, though they have no right to be. Part of the reason fallacies are so pernicious and pervasive is that they often appear to be good reasons, though this is just an illusion. After six chapters spent grappling with critical thinking concepts, I believe you’ll be much more immune to using and accepting these types of reasons.

The following list of a dozen or so informal fallacies isn’t exhaustive. No one has catalogued all possible instances of a garbage reason, which would probably be impossible (you can search for other lists that have been published – they run into the hundreds). The purpose of this list, and my approach to organising them, is to give you a sense of how and why these reasons are inadmissible, not for you to memorise a bunch of Latin words (this isn’t a Latin text). In this way, you don’t need to know the names of all the fallacies to sniff out inadequate and inadmissible reasons.

Another qualifier to keep in mind is that even this scheme for organising the fallacies is by no means agreed upon. You’re just as likely to come across systems that articulate four types of fallacies. There also might be other schemes that put some of the bellow fallacies into a different category (for example, some fallacies of insufficiency could also be thought of as fallacies of irrelevancy). There’s no right or wrong way to organise these, but grouping them does illustrate the more general and useful principles underlying them, so I went with the 3-grouping fallacy typology because it seems slightly simpler. These groups are: (1) insufficient reasons, (2) irrelevant reasons, and (3) ambiguous reasons.

Fallacy Group 1: Insufficient Reasons

Insufficient premises are those that represent inadequate or ‘not enough’ types of evidence and reasons to support the conclusion. When insufficient reasons are offered as premises with no additional supporting premises or their own argument underpinning them, it’s something like an unjustified assumption. The onus is always on the person offering the argument to provide sufficient evidence or reasoning to support their conclusion. For this reason, they commit fallacies of insufficiency. After a few examples, you’ll have a more secure grasp of what these fallacies are all about. Many of these fallacies involve failures to properly construct legitimate versions of inductive arguments that we covered last chapter: enumerative inductions to a future case (predictive induction), generalisations, arguments from analogy, and cause and effect reasoning.

Fallacies of insufficiency are often reasons that are offered as though they were convincing in isolation – yet most of these fallacies wouldn’t be so terrible if additional premises were included to provide sufficient evidence. Therefore, these are often fallacious because the arguments are somehow incomplete.

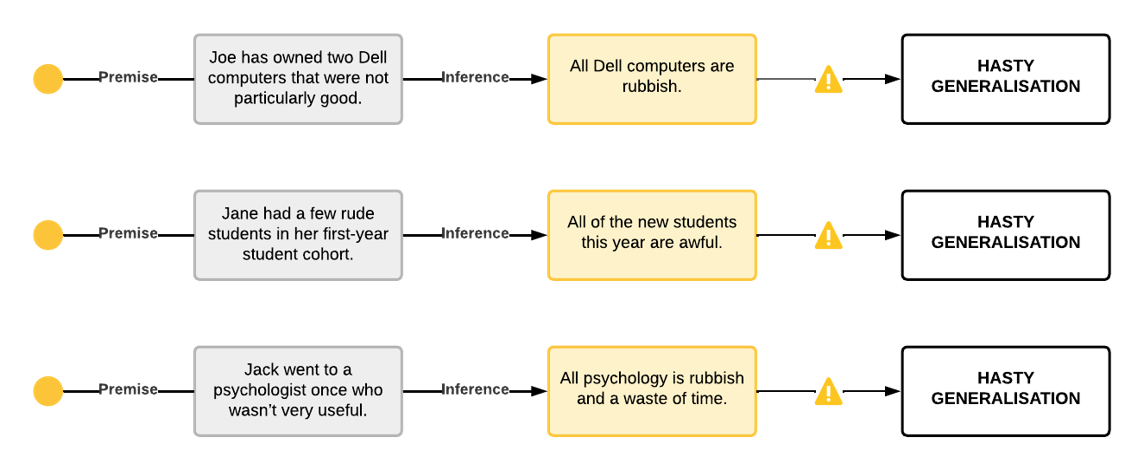

Hasty Generalisation

As we saw last chapter, many inductive arguments seek to establish a generalisation about a whole class or group of objects from a finite sample. Many times, however, that sample is inappropriate, small, or biased. Without any additional evidence or rationale provided to justify these samples, the propositions that form the premises are woefully inadequate to establish the generalised conclusion.

This fallacy involves reaching an inductive generalisation based on a faulty or inadequate sample. It’s fallacious because the inadequate instances sampled aren’t a good reason for believing in the generalisation. This type of fallacy also leads to stereotyping and prejudice. In fact, as we learned in Chapter 3, prejudices and stereotypes often result from our desperation to cling to weak, category-derived information, or to overextend (generalise) this information to inappropriate cases. Part of the motivation for this is to act as a security against the anxiety caused by our ignorance.

Generalisation fallacies are all too common. There are some specific types that are not identical to, but are related to hasty generalisation such as ‘insufficient sample’, ‘a converse accident’, ‘a faulty generalisation’, ‘a biased generalisation’, ‘jumping to a conclusion’, etc.

Examples:

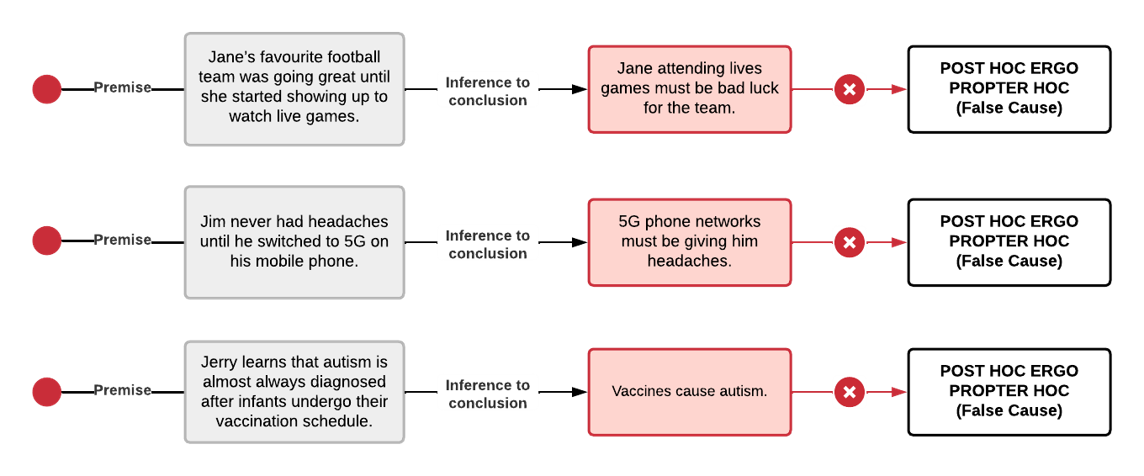

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (False Cause)

This fallacy translates from Latin as ‘after this, therefore because of this’ and it’s often shortened to ‘post hoc fallacy’. This fallacy involves reading causality into a sequence of events. As we know from the last chapter, identifying and establishing causal relationships is one of the main uses of inductive reasoning – however, it’s incredibly difficult to establish with any certainty. Thus, an all-too-common pitfall of these types of inductive arguments is to infer causality with insufficient evidence or reasons. One example of this is the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy.

To have a credible inference to a cause and effect relationship, you need to establish at least three things:

- the two phenomena are, in fact, related (correlation has to exist)

- the supposed cause precedes the effect in time (effects can’t come before their causes

- other potential causes and confounds are not interfering and confusing the issue.

Strong inductive arguments must address all of these in the premises. Fallacies of insufficiency relating to causal inferences occurs when premises are offered that don’t tick all these boxes. The fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc is one example of this type of fallacious causal inference. It’s simply a premature inference that there is a cause and effect relationship in the absence of fully satisfying all three conditions. This is why it’s an example of insufficient reasoning. Just because something regularly occurs after something else doesn’t make them causally related – they may not be connected in any way whatsoever. Examples of this abound in all sorts of superstitious thinking.

Examples:

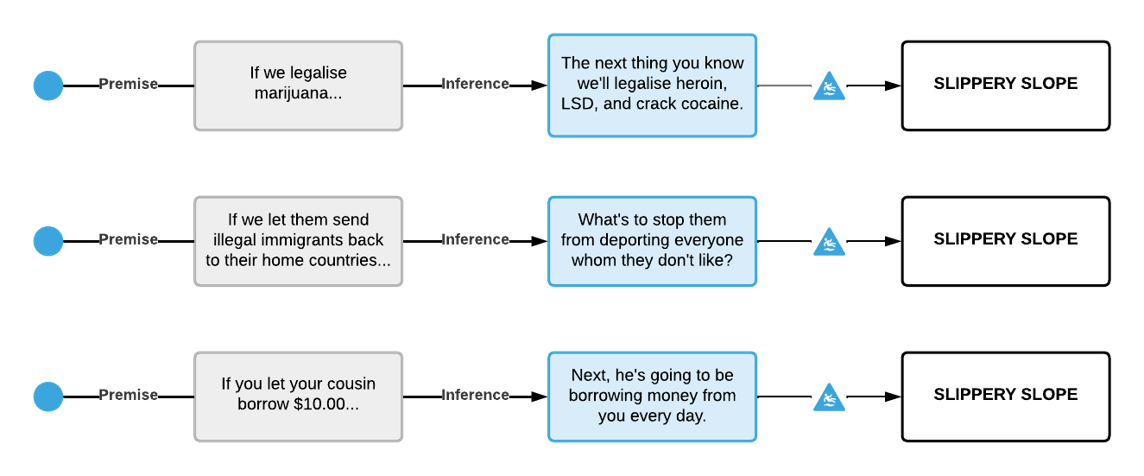

Slippery Slope

Invoking a slippery slope as a premise is another instance of a fallacy of insufficiency. This is because consequences are inferred for which no evidence or rationale is provided – except that one step forward is claimed to trigger a chain of events that have significant and dire consequences. Of course, any claims about future events must be supported by their own reasons and arguments and not merely assumed. When arguments contain a ‘You give an inch, they take a mile’ type of reasoning, they’re appealing to a ‘domino effect’ or a ‘chain reaction’ (sometimes this fallacy is referred to using these terms). These arguments are also sometimes coupled with fallacies of inevitability or ‘appeal to fear’. Like most informal fallacies of the insufficiency type, they’re not always fallacious – only when they’re overreaching and incomplete. These fallacies can easily be turned into good arguments by providing the necessary additional reasoning and evidence to support the claim that the events will proceed in a slippery slope.

Examples:

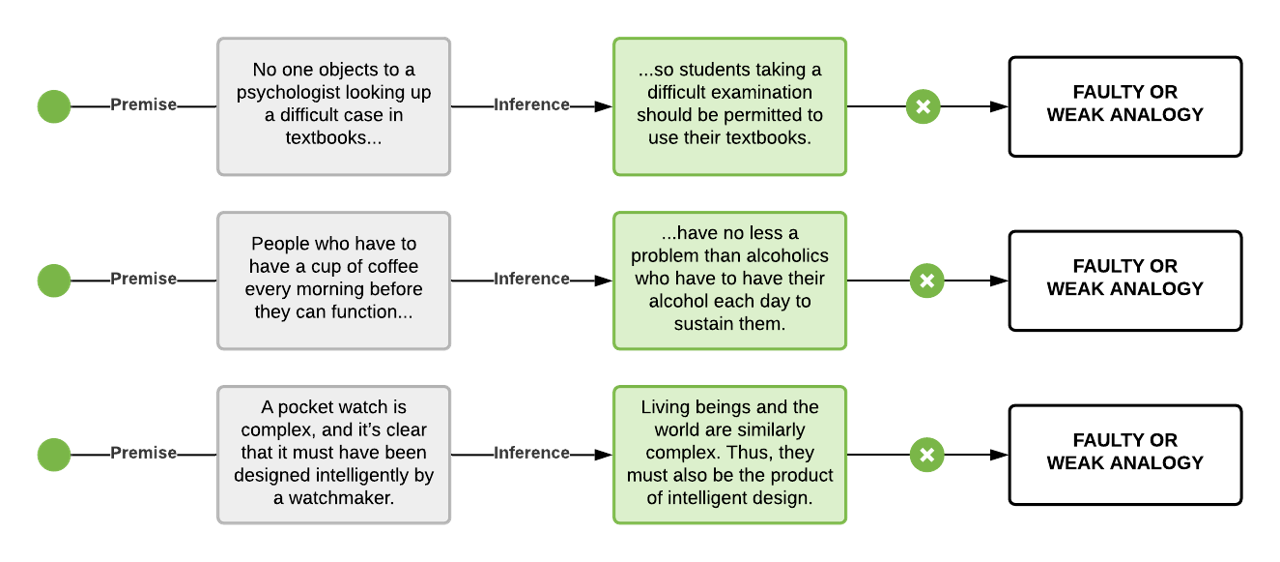

Faulty or Weak Analogy

Like fallacies that involve causality and generalisation that we discussed above, a faulty or weak analogy is an instance where a potentially legitimate form of induction has gone wrong because the reasons are insufficient and/or incomplete. We learned last chapter that analogy is one of the major strategies for inductive reasoning, and yet, like inferences that invoke causality and generalisation, these arguments very easily become fallacious. When two things claimed to be analogous aren’t alike in enough ways that matter, we have a faulty or weak analogy.

This fallacy goes by a few other names as well (like most informal fallacies) and some of the more common ones are ‘bad analogy’, ‘false analogy’, ‘faulty analogy’, ‘questionable analogy’, ‘argument from spurious similarity’, and ‘false metaphor’.

Examples:

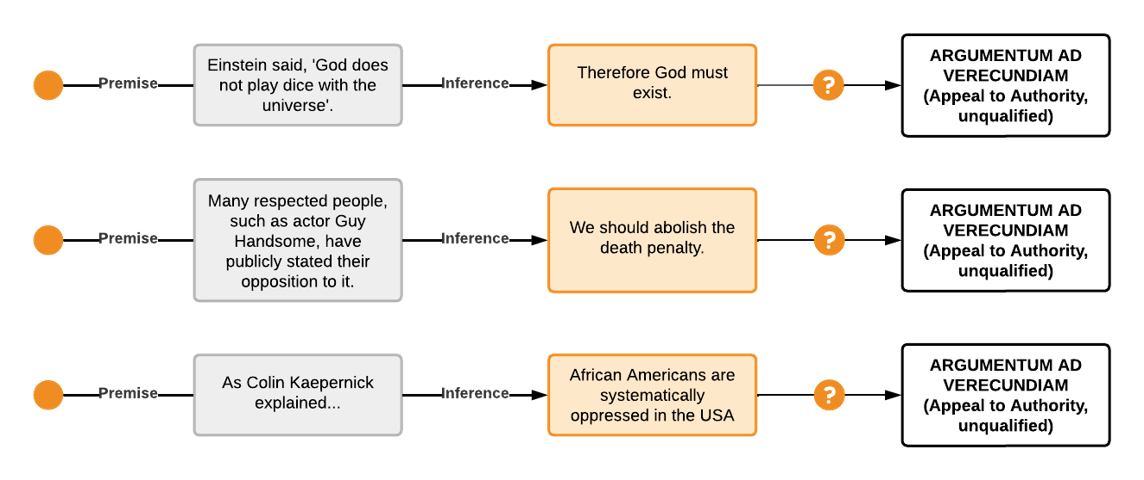

Argumentum ad Verecundiam (Appeal to Authority, Unqualified)

This one could also have been grouped under fallacies due to irrelevance since, in most cases, an appeal to a supposed authority figure is completely irrelevant to the claim. However, it’s also an example of an insufficient reason because in the absence of more information and verification, the appeal to an authority is unconvincing. As the name gives away, this one is quite straightforward, yet no less commonly smuggled into arguments, especially informal conversations. Appealing to some authority figure as a source or an adherent of a claim simply provides no reason at all for believing that claim. There are a million crazy ideas believed by some of the most brilliant and gifted people of all time. Newton was obsessed with alchemy and apocalyptic prophecies and spent more time working on these projects than he did on actual science. You’ll bump into this fallacy a lot on social media where people will quote Einstein’s position on politics, which is about as legitimate as quoting a political scientist as a reason for believing something relating to special relativity theory (or Deepak Chopra on quantum theory).

As with most of the other fallacies in this section, there is a legitimate way to appeal to an authority, and that’s if that person has specific expertise in the area. However, the appeal to authority in this case is more of a shorthand for appealing to the leading scientific theories and evidence of the day. In this way, it isn’t actually the person that can legitimise a claim, but what they might represent. However, it’s always more convincing and safer to simply appeal to actual reasons and evidence, not people. For example, it isn’t fallacious to quote Stephen Hawking on the subject of black holes. But it isn’t Hawking’s authority that makes the claim compelling – rather, he’s a placeholder for the latest scientific reasoning and evidence on the matter. This is also the case when we take medical advice from our doctor. It isn’t that we believe they have powers to see into the future, but just that when they tell us that our condition will improve after x, y, z, treatment, they’re a placeholder and mouthpiece for the latest medical research and theories on the matter.

Arguments that cite authority figures who have no special expertise on the relevant topic are committing this fallacy. Additionally, arguments that cite someone with supposed expertise without the willingness to provide verification for why their expertise is compelling are also guilty of very weak argumentation. For example, the claim ‘Because 97 per cent of climate scientists believe in man-made climate change, it must be real’ isn’t necessarily fallacious, but it’s still a very unpersuasive argument. I find appeals to authority are often used out of laziness.

Examples:

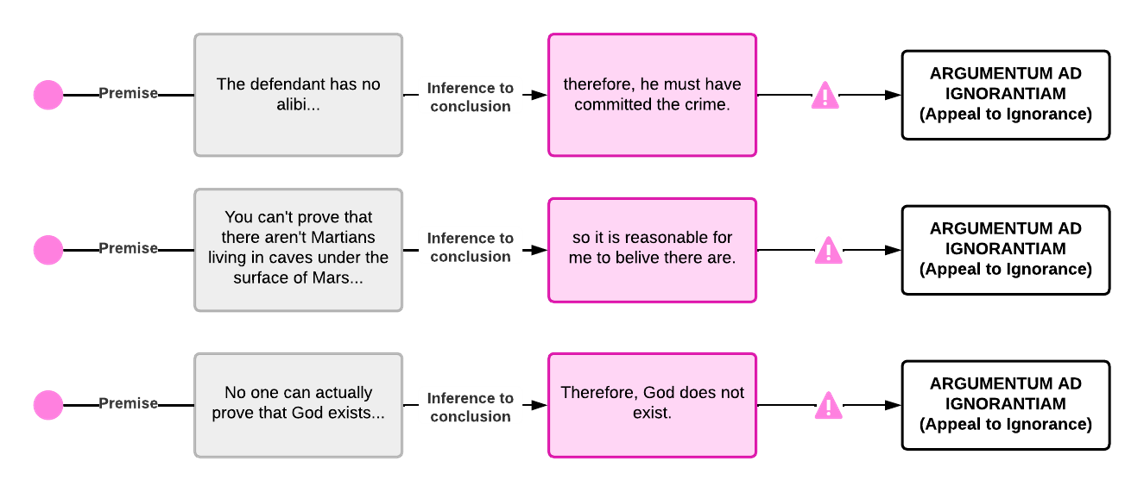

Argumentum ad Ignorantiam (Appeal to Ignorance)

This common fallacy is the act of reasoning for a claim because there is no evidence to disprove it. Things aren’t true until disproven – rational thinking doesn’t work that way. Appeals to ignorance are often part of attempts to shift the ‘burden of proof’ (another fallacy). The key point is that anyone making a positive claim adopts the burden of proof for supporting it with reasons and evidence. Anyone presenting an argument must provide supporting evidence and reasons, and not merely claim there’s no evidence against it. A lack of evidence is evidence of nothing and can’t be used to support any positive conclusion. You’ll come across this fallacy in many areas of our culture, and even the fringes of some sciences that are especially prone to pseudoscience. These include sport sciences, the dieting and supplement industry, the beauty product industry, etc.

People are likely to use this tactic if they have very strong beliefs in something. They require these beliefs to be disproved, rather than requiring any evidence to support them in the first place. For example, if someone is a passionate adherent of astrology, they may require you to marshal evidence to show why it’s false, rather than a willingness to offer the evidence for its truthfulness. The best stance to adopt is one of reserved judgement (scepticism), just as we talked about in Chapter 2. Believe nothing until there is evidence and a strong rationale to do so.

One caveat to keep in mind is that sometimes in scientific studies we attempt to find evidence of something, but when the study doesn’t support the hypothesis, this can be a convincing argument. But what really matters here is that there was a dedicated attempt to find evidence to support something. This isn’t an appeal to ignorance, though it might sound that way. When someone says something like ‘There’s no evidence that childhood vaccinations are linked to autism’, it isn’t fallacious. This is because scientists have spent decades conducting many different types of studies to try to find such a link – however, they’ve been unable to find any evidence that the hypothesised link exists. In this case, it isn’t fallacious to accept this (lack of) evidence as a compelling reason not to believe vaccines are linked with autism.

Examples:

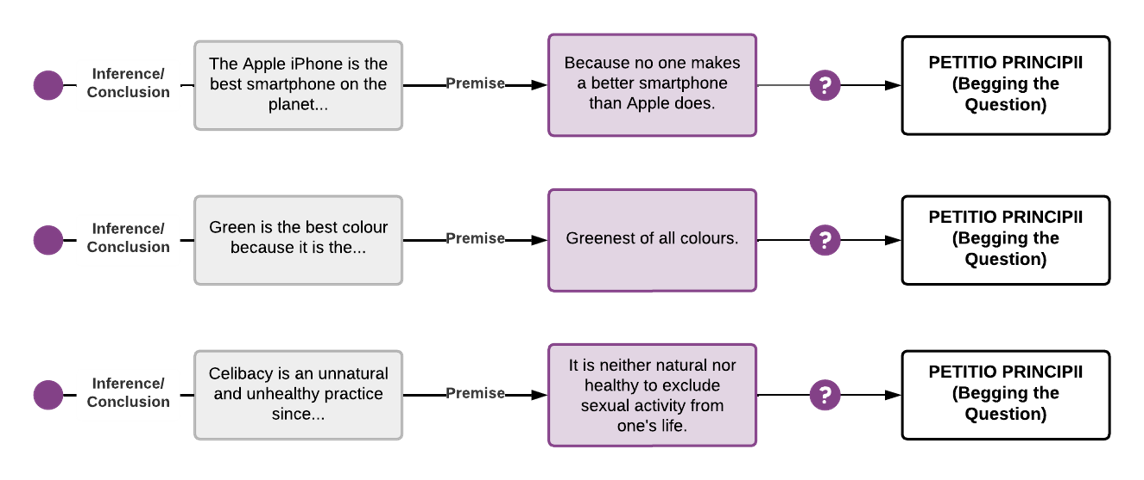

Petitio Principii (Begging the Question)

Petito principii is the fallacy of using whatever you’re trying to prove as a premise. That is, embedding or assuming the conclusion in the premises. In this way, the conclusion is already assumed, but usually in a different form in the premises. Begging the question isn’t used in its commonly understood everyday sense of ‘John is smart, and it begs the question: Why is he with that girl?’. This version of the phrase ‘begs the question’, points to something that’s difficult to explain, as though there is an obvious question that one is begging for an answer to.

The fallacious tactic ‘begging the question’ is more circular in reasoning. For example, ‘I’m confident God exists because it says so in the Bible, and the Bible contains God’s word’. So the book is what verifies God, and God is what verifies the book. In this way, each part of the argument assumes the other part, so each ‘begs the question’ (I understand this is confusing since there’s no question here). Another example can illustrate this circularity: ‘Everyone wants the new iPhone because it’s the hottest new gadget on the market!’, but the premise or reason that ‘It’s the hottest new gadget on the market!’, isn’t actually saying anything different from the conclusion. The fact that it’s the ‘hottest new gadget’ is saying the same thing as ‘everyone wants it’. In this way, the premise is nothing more than a restatement of the conclusion, and thus, begs the question: ‘Where are the actual reasons and evidence?’.

Sometimes this fallacy is called ‘circulus in probando’, ‘circular argument’ or ‘vicious circle’.

Examples:

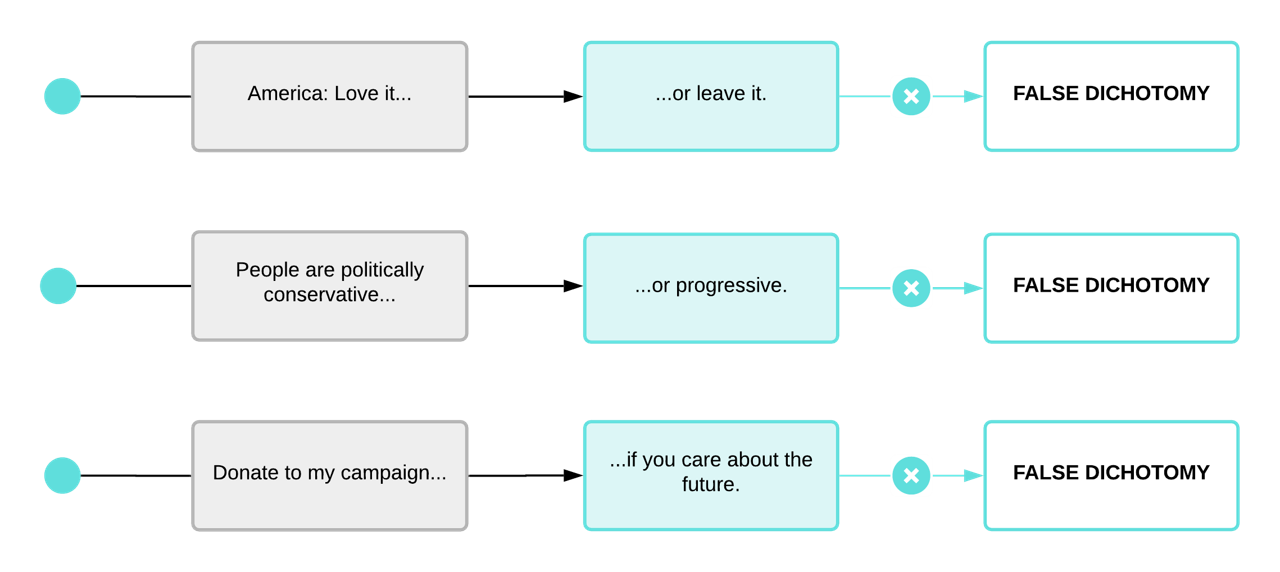

False Dichotomy

This is a case of artificially offering only two mutually exclusive alternatives, when in reality, there are many more options. There are almost always countless variations in possibilities between any two extremes. In many arguments, you’re presented with two extremes or two options to pigeonhole you into one or the other. This is essentially a problem or strategy of oversimplification in which one or more alternatives is omitted, usually purposefully. Look out for key words such as the phrase ‘the alternative’, as there is almost never a single alternative. You might also detect this one when you see the use of ‘or’ in the premises. These are very common in political speeches. Generally, the aim here is to limit your awareness of available choices so the choice being offered by the person trying to persuade you seems like the better option.

This fallacy is known by many names. Sometimes it’s called ‘false dilemma’, ‘all or nothing fallacy’, ‘false dichotomy [form of]’, ‘either/or fallacy’, ‘either/or reasoning’, ‘fallacy of false choice’, ‘fallacy of false alternatives’, ‘black and white thinking’, ‘fallacy of exhaustive hypotheses’, ‘bifurcation’, ‘excluded middle’, ‘no middle ground’, ‘polarisation’, etc. Note here the phrase ‘excluded middle’ isn’t to be confused with the formal fallacy of a similar name, which is concerned with the middle term in categorical syllogisms.

Examples:

Fallacy Group 2: Irrelevant Reasons

As opposed to fallacies of insufficiency, irrelevant reasons are often easier to spot. Insufficient reasons are more a case of potentially legitimate arguments that are missing important pieces and, for that reason, are unpersuasive. Irrelevant reasons are fallacies that introduce premises that have nothing whatsoever to do with the claim being made. While insufficient fallacies are simply lacking justification – be it extra evidence, reasons, or details – fallacies of relevance are more a matter of changing the subject entirely. The relevancy of specific premises offered as reasons is something you must decide on a case by case basis – as in, it’s dependent on what the claim is about. For example, it’s fallacious to dismiss vegetarianism just because an evil person like Hitler advocated for it. However, it isn’t fallacious to be sceptical of Hitler’s human rights policies on the grounds that he is an evil person, because in this case, that’s relevant. Appealing to Hitler is a common fallacy of irrelevance, which even has a tongue in cheek Latin name now (‘Reductio ad Hitlerum’) and is also known as ‘playing the Nazi card’.

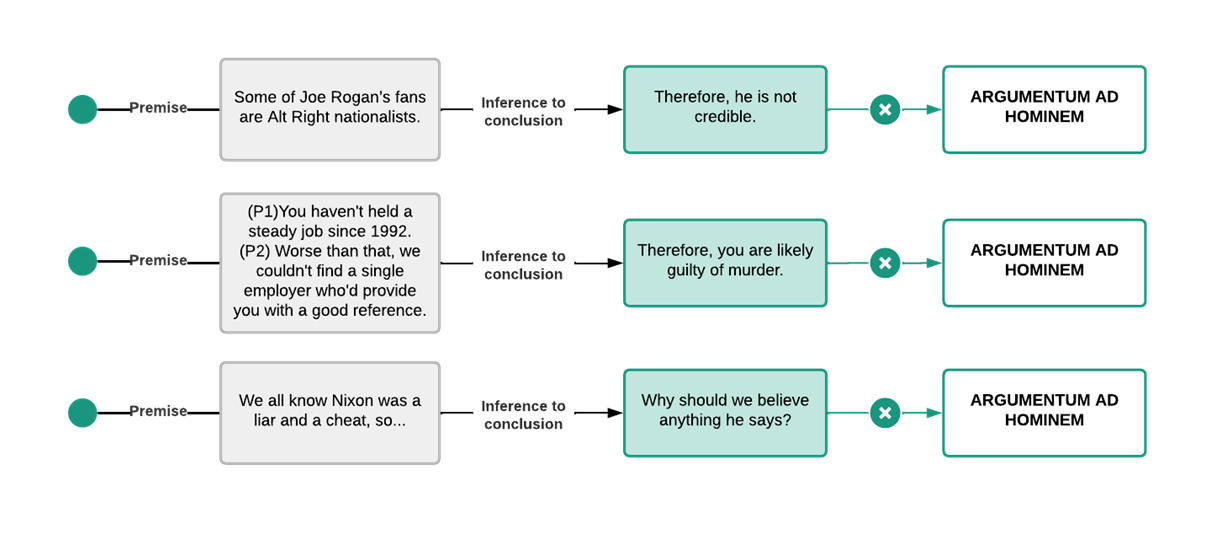

Argumentum ad Hominem

This translates as ‘against the man’ and is a case where a proposition is dismissed because of some characteristic of the people presenting or believing it. This fallacy is committed when irrelevant premises referring to individuals opposing you and not the facts are appealed to (of course, an exception would be when an argument is about a specific person). In this way, the argument is sidetracked from focusing on the quality of the reasons or evidence against the claim itself, and instead focuses on the quality of the people presenting it – usually by casting aspersions on their character or motives. The most obvious answer is when one debater tries to malign or undermine their opponent’s credibility. The strategy is to create prejudice against a person to avoid dealing with their arguments. ‘Ad hominem attacks’ are most commonly seen in political debates that descend into name-calling without anyone actually reasoning through the issues.

One thing that students often get confused by is thinking that ad hominem refers to any attack on any person’s character. This is not the case. It’s specifically an attack on the person opposing your viewpoint because it’s fallacious to criticise that person instead of dealing with their arguments. It’s not necessarily an ad hominem fallacy to criticise or sledge people not involved in a debate (though this might not be very persuasive).

The reason these are fallacies of irrelevance is fairly simple. It doesn’t matter whether it was Hitler or Stalin who told you that 2+2=4 – their character or value as human beings has nothing whatsoever to do with the argument underpinning the claim.

Examples:

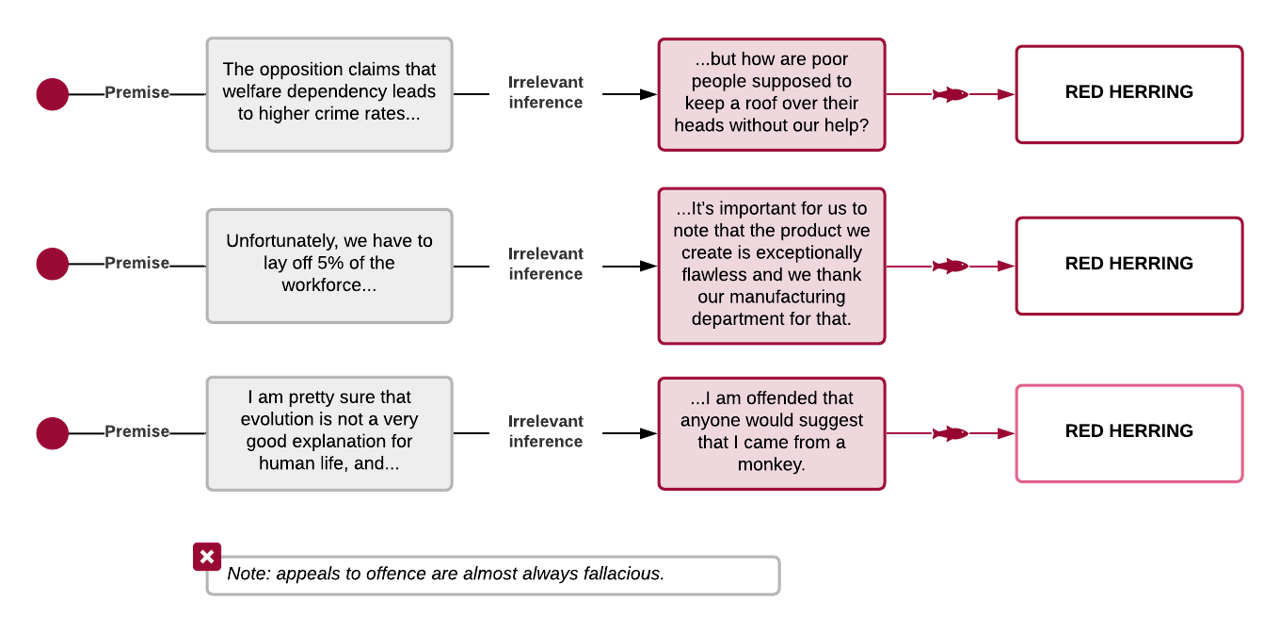

Red Herring

‘Red herring’ is a phrase from hunting. It refers to any strategy for distracting attention. This is a prototypical type of fallacy of irrelevance – it’s an active attempt to change the topic or of introducing irrelevant facts or arguments to distract from the issues at hand. One doesn’t have to deal with the claims and arguments if the topic is changed altogether. ‘Ad hominem attacks’ are also useful ‘red herrings’ since the opponent invariably launches into a defence of their own character, and the accuser is now off the hook for having to actually address the arguments being stated. The red herring is a not so clever diversion technique that’s often a last resort from a debater who simply can’t address the reasons and evidence of their opponent.

Sometimes this fallacy is called ‘befogging the issue’, ‘diversion’, ‘ignoratio elenchi’, ‘ignoring the issue’, ‘irrelevant conclusion’, or ‘irrelevant thesis’.

Examples:

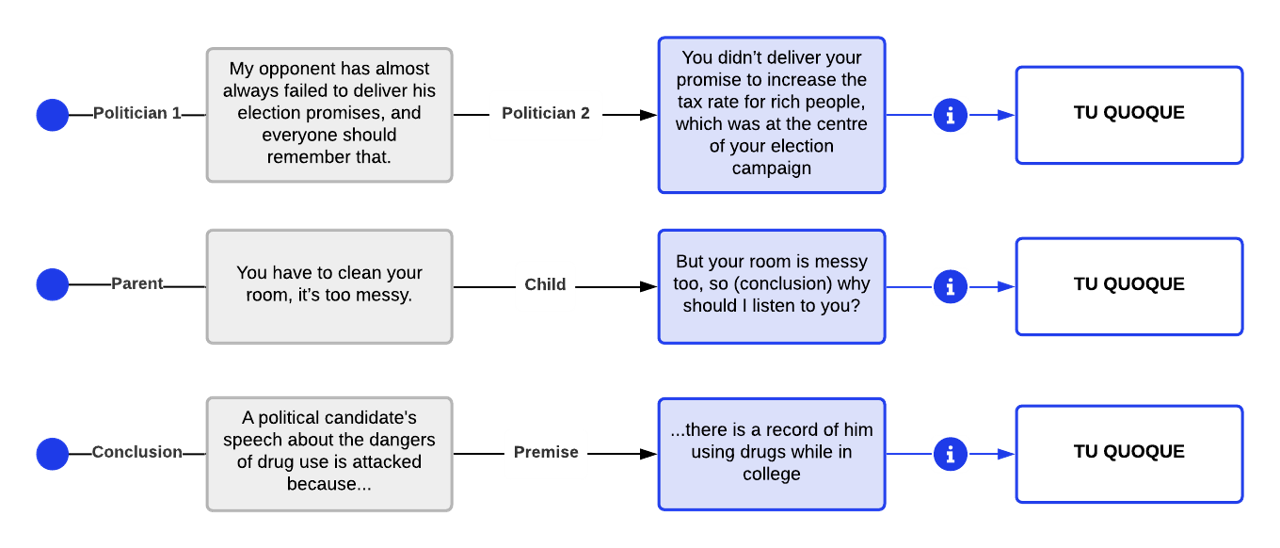

Tu Quoque Fallacy

This translates from Latin as ‘You too’, meaning, ‘Who are you to talk?’. This tactic is used to deflect attention back to the person making the claim and their own past actions or words. In a way, it’s a ‘charge of hypocrisy’ intended to discredit the person presenting the claims. ‘Tu quoque’ is a type of ad hominem also used as a red herring device. In this case, the argument is being dismissed because the one making the argument isn’t acting consistently with the claims of the argument. An obvious example of this is dismissing health advice from an overweight doctor or one who smokes. You might struggle to swallow this advice from the doctor, but the health advice isn’t wrong due to the smoking or weight issue. It’s fallacious because the behaviour of the person presenting the facts has nothing to do with those facts.

Examples:

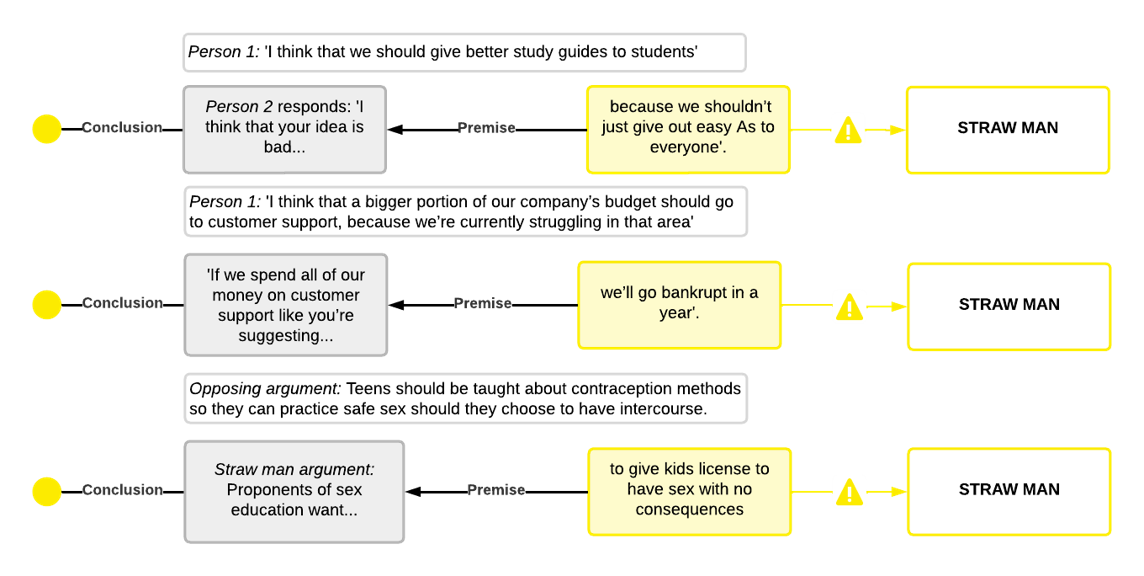

Straw Man

This excellently named fallacy is a case of oversimplifying or misrepresenting your opponent’s argument so it’s easier to defeat. A man made of straw is easier to defeat than a living, breathing one, so this fallacy is a strategy of turning your opponent’s position into a ‘straw man’ and making it easy to knock over. This is a common tactic when a debater doesn’t have enough reasons or evidence to dismiss their opponent’s claims. Instead, they can simply distort those claims and defeat the distorted versions. Sometimes the person committing the straw man will intentionally caricature or present an extreme or silly representation of the opponent’s claims. Often, the distorted version of the opponent’s debate is only remotely related to the original. The distortion may focus on just one aspect of the claim, take it out of context, or exaggerate it.

This is very common in everyday conversations, as well as debates over contentious issues. We routinely put words into people’s mouths, and thereby, have an argument with a straw man. Straw man arguments can be rather effective, and can sometimes entice an opponent into defending a silly version of their own position.

Some of these fallacies can be used in combination. For example, a good straw man (one that’s silly, but not too dissimilar to the opponent’s true position) is actually a useful red herring as it distracts the audience from the real claims and evidence of the opponent.

Examples:

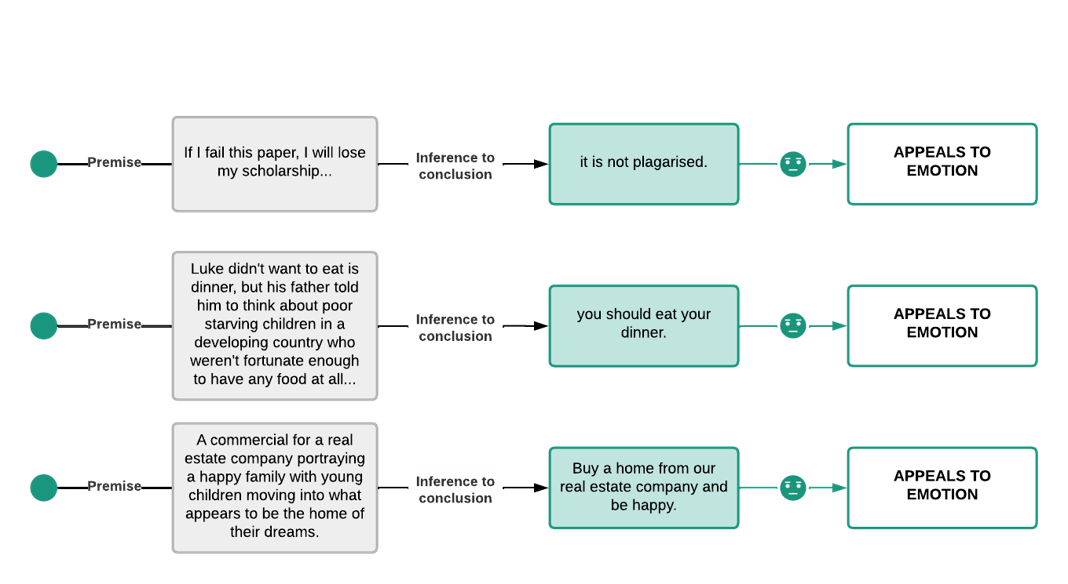

Appeals to Emotion

This is a general category of highly persuasive fallacies that contain a number of very common argumentation tactics. Generally speaking, these tactics attempt to produce acceptance of claims by manipulating the audiences’ emotional state. These are clearly ‘fallacies of irrelevance’ – we should only ever be convinced by reasoning and evidence, not be influenced by our emotional state, which could have nothing to do with the truth of a claim.

We humans are very vulnerable to emotional manipulation, since emotions quite rightly influence our reasoning daily. Therefore, it’s a powerful rhetorical technique to attempt to elicit certain emotional states in another person to make them more amenable to your points. Fallacies under this heading can include any ‘appeals to emotion’ that take the place of reasoning and evidence. Common instances include ‘appeal to pity’, ‘appeal to fear’, ‘appeal to joy’, ‘appeal to pride’ – the list goes on. Getting an emotional reaction from an audience can be a much easier and more powerful way to convince them that certain claims are true.

Some flexibility is required in applying the charge of ‘fallacy of appealing to emotion’. Note that appeals to emotion aren’t necessarily fallacious when used in moral reasoning because eliciting certain emotional reactions is relevant to our moral position on important issues. Further, when the purpose of the argument is to motivate us to action, then emotional experiences may not be irrelevant. But always remember that emotion should never take the place of reasoning and evidence, and certainly should never be used to suppress or dismiss reasoning and facts. Sometimes facts are uncomfortable and unpleasant, but feelings never surpass facts.

Examples:

Fallacy Group 3: Ambiguous Reasons

Fallacies of insufficiency occur when something is missing or simply inadequate as a reason or evidence for a claim; fallacies of irrelevance occur when premises are introduced that have nothing whatsoever to do with the claim being made; finally, fallacies of ambiguity involve unintentional or intentional confusion over the meaning of what is being offered as a reason or piece of evidence. In this way, a fallacy can involve a lack of clarity or a misunderstanding of the words. Sometimes fallacies of ambiguity occur when the meaning of a word or phrase shifts within the course of an argument. An ambiguous word or phrase is one that has more than one clear meaning. Ambiguous terms, phrases, and arguments are unclear and unpersuasive. While fallacies of insufficiency often arise out of laziness or inattentiveness, fallacies of ambiguity and irrelevance are often intentionally misleading.

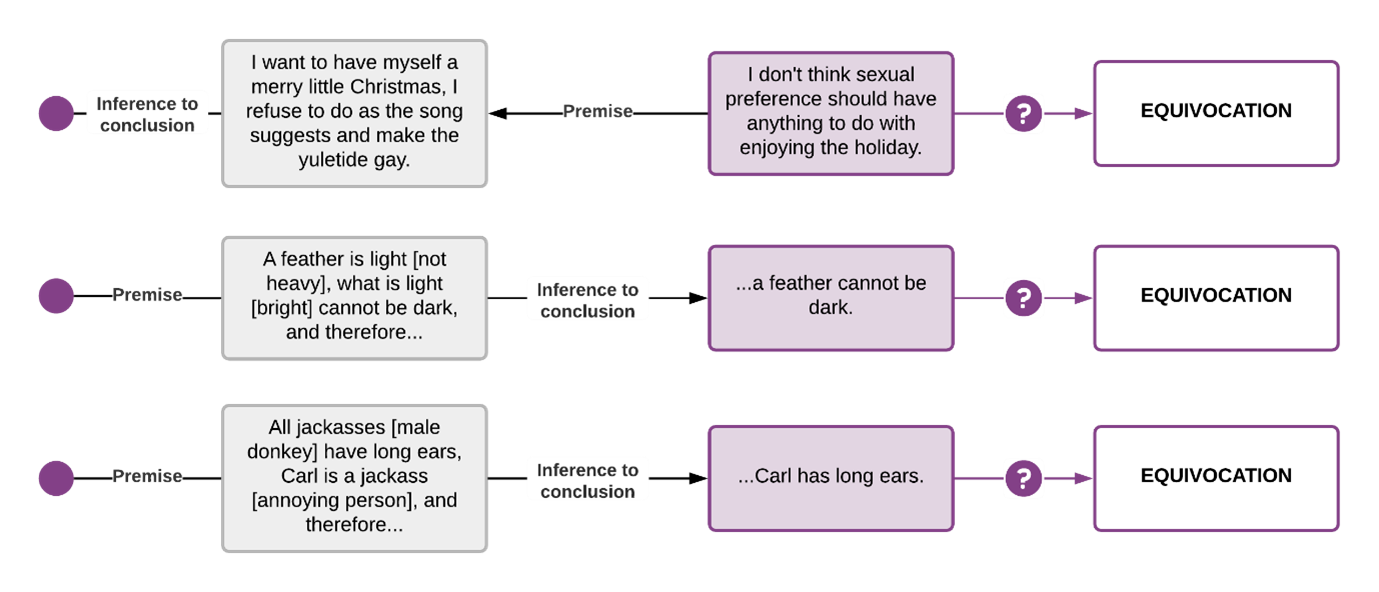

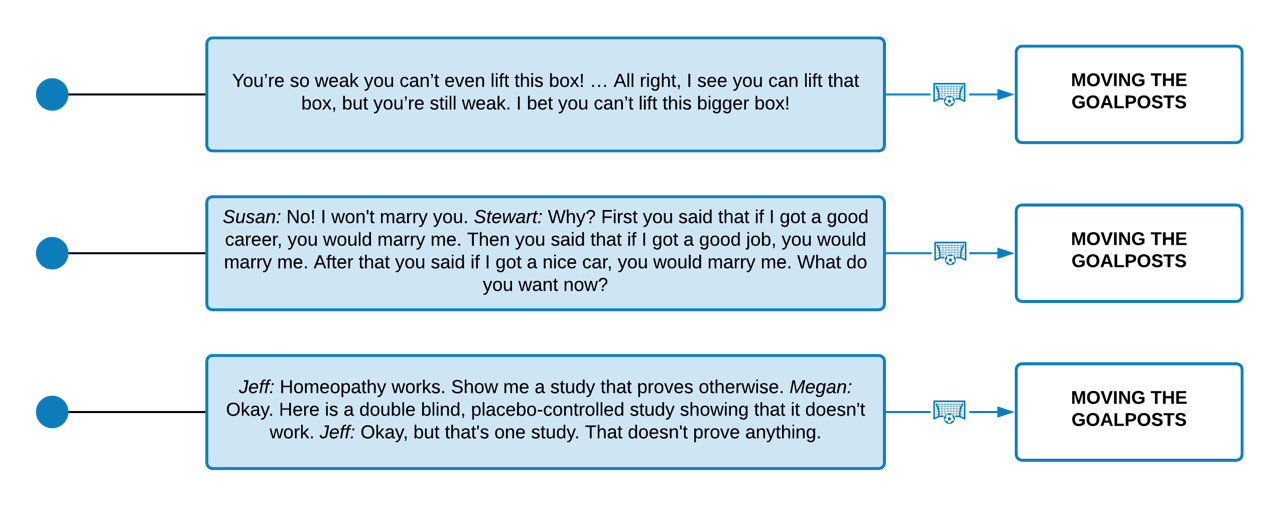

Equivocation

The meaning of reasons and evidence offered as propositions in arguments is a product of the meaning of the words they’re made up of. One challenge introduced by this is that words often have multiple – and even unrelated – meanings. Equivocation means calling two things by the same name inside an argument. It isn’t a problem if a word like ‘gay’ has several meanings, but the onus is on the person making the claim and presenting the argument to use their terms in the same sense (referring to the same things) throughout their argument. This fallacy occurs when a certain term or expression is used in two different ways throughout an argument. It isn’t difficult to come across obviously silly examples such as ‘Since only man [human] is rational and no woman is a man, no woman is rational’. However, it can be rather difficult to notice when a shift in a word’s meaning has occurred when it’s a subtle one. This is also sometimes paired with a ‘shifting goalposts fallacy’ in which a person cleverly uses language to make the target evidence or reason demanded increasingly difficult to achieve.

Not much additional explanation is required to make sense out of this fallacy, except to say – inspect the meaning of the words in a debate very carefully and ensure the words are used in same sense throughout (we first confronted the necessity of being very careful with language and meaning in Chapter 2 under the first appraisal ‘meaning analysis’).

Examples:

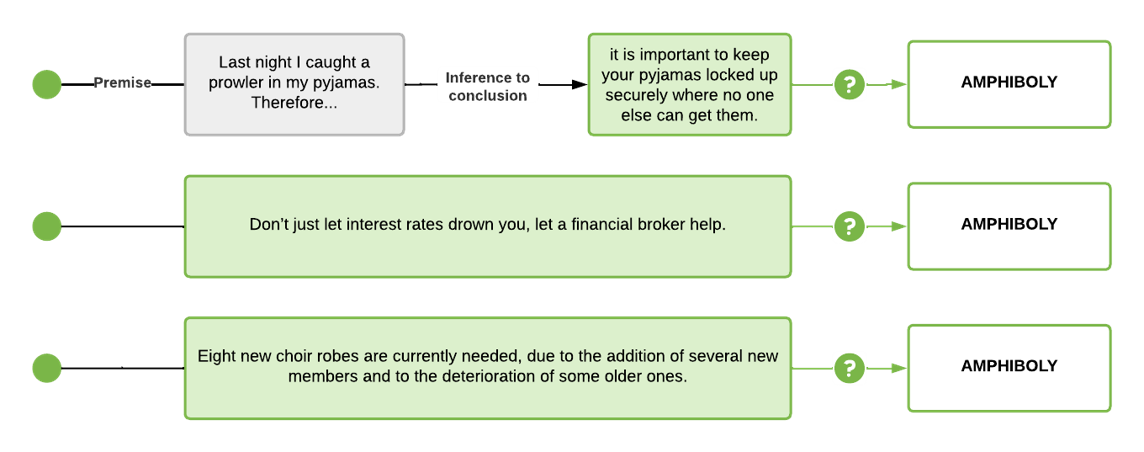

Amphiboly

Amphiboly is a Greek word meaning ‘double’ or ‘on both sides’ (this is a nice break from all the Latin we’ve been confronting). A ‘fallacy of amphiboly’ occurs when the meaning of a phrase or sentence is indeterminate or ambiguous. Amphiboly occurs when the grammar of a statement allows for several distinct meanings. The equivocation fallacy referred to above is word-sized, whereas the amphiboly fallacy is sentence- or phrase-sized. Therefore, it’s the use of sentences that have multiple possible meanings. This fallacy is often achieved by incorporating a complex expression (e.g. ‘I shot an elephant in my pyjamas’) with multiple possible meanings to smuggle in or camouflage one’s true point. Like the equivocation fallacy, you can have some fun with the examples for this one.

Examples:

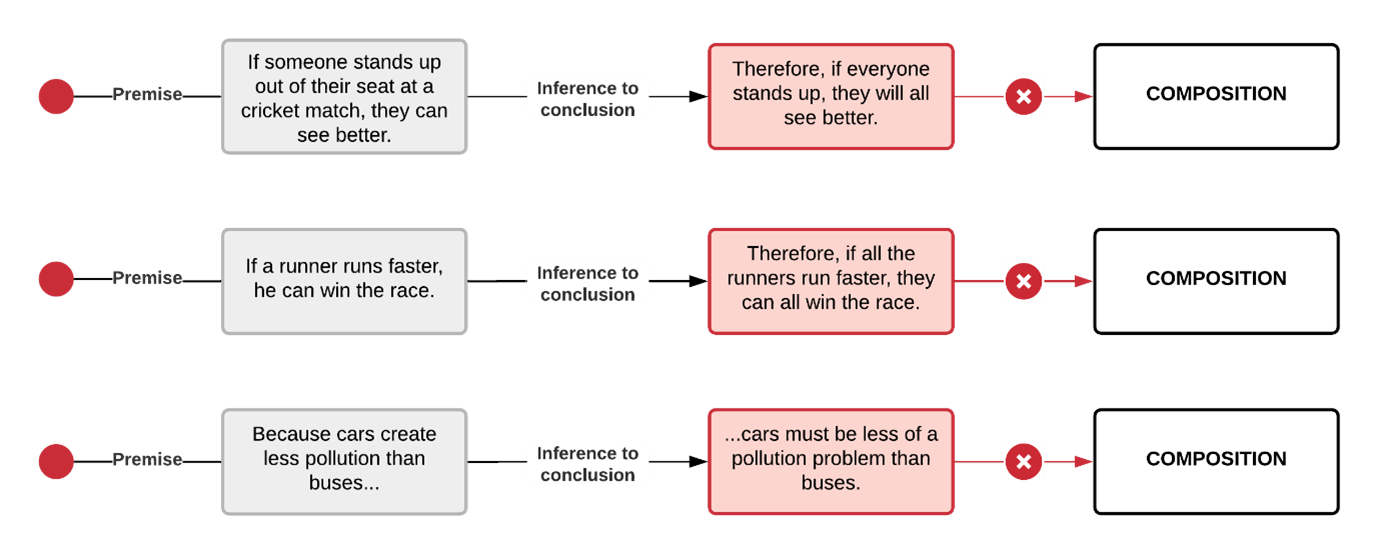

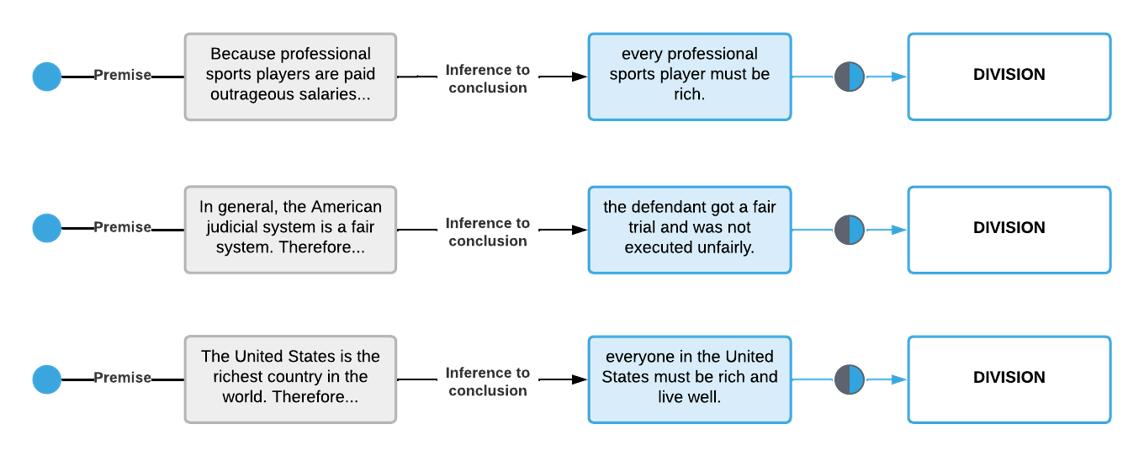

Composition

This fallacy relates to how things are put together or ‘composed’. The general tactic is to infer that when something is true of a part, it’s true of the whole (or a bigger part of the whole). Stated like this, you might think that this is simply trivial and hardly ever persuasive. Certainly, the trivial examples offered for it (including the ones below) do give the impression it’s rarely a useful strategy. However, man y view this fallacy as ubiquitous and highly significant. While we know it stands to reason that what is true of parts isn’t necessarily true of the whole, we commit – and fall prey to – this fallacy all the time. Another trivial, but very common, instance of this reasoning is when we believe that because our sport team has the best players in all the positions, they’ll be the best team in the league. Yet, we know from painful history that the whole isn’t reducible to the sum of its parts.

The ‘fallacy of composition’ is the opposite of the ‘fallacy of division’, which we’ll look at next. This fallacy has some overlap with hasty generalisation, in which the whole population is believed to be identical or represented by characteristics held by one part (the sample).

This fallacy is also known as the ‘composition fallacy’, ‘exception fallacy’, and ‘faulty induction’.

Examples:

Division

Here, the situation in the fallacy of composition above is reversed, and the inference is that something that’s true for a whole must also be true of all – or some – of its parts. But just because a collective whole has a certain property, doesn’t mean any of its parts will have that same property. Just as generalising from a small non-random sample to a population is fraught with danger and likely fallacious, it’s equally so when generalising from something known about a population to an individual case or sample. We see this a lot in racial stereotyping, where we might think because on average certain ethnic groups are unhealthier, have lower educational outcomes, or are convicted of more crimes, etc. then any given case must also share this characteristic. However, it’s silly to assume that any individual member of a group has the same generalised property known to exist at a group or average level.

This fallacy is also known as ‘false division’ and ‘faulty deduction’ (the reference to deduction here is confusing, so don’t give it too much weight.).

Examples:

Moving the Goalposts

‘Moving the goalposts’ (or shifting the goalposts) is a metaphor borrowed from sport to represent a changing of the target in order to gain advantage. This tactic can commonly be seen in debates. A debater might be ambiguous about what they’ll accept as a compelling reason or piece of evidence so that when it’s presented, they can rearrange the goalposts and avoid defeat. For example, a creationist may ask, ‘Show me an example of something evolving today’ or ‘Show me an example of information increasing through random processes’, only to then change the meaning of the terms or standards of evidence that are acceptable. The issue here is that the terms are ambiguous enough to support a range of different meanings of evolution, information, randomness, etc. The strategy is straightforward and involves demanding more and more difficult and rigorous standards are met before one will accept a claim. No matter how much evidence or reasoning is offered, we can always escalate our demands for infinitely more evidence and reasons. In this way, we avoid ever having to concede defeat.

It’s important to always be clear to ourselves and those we’re in discussion with about what counts as evidence or a compelling reason, and stick consistently to this. Unfortunately, it’s human nature to resist defeat at all costs, and so when the evidence is applied, we change our mind about what evidence is acceptable and what isn’t. It’s important to ensure both parties are clear on what evidence or reasoning they will accept as conclusive about an issue. Once someone commits to this, it’s more difficult for them to run away with the goalposts.

This fallacy is also known as ‘gravity game’, ‘raising the bar’, ‘argument by demanding impossible perfection’, and ‘shifting sands’.

Examples:

Cognitive Biases

Many of the fallacies above exist because they can be very persuasive. This is because many are rooted in cognitive biases. That is, we have in-built vulnerabilities to be persuaded by certain underhanded, unconvincing, incomplete, ambiguous, or irrelevant information and reasoning. This is particularly relevant for the current chapter, since it’s concerned with reasoning critically. One of the major reasons we fail at achieving this is due to our blindness to a range of cognitive biases that get in our way.

We defined ‘cognitive bias’ back in Chapter 3. But let’s refresh this. Cognitive biases are systematic ways in which the context and framing of information influence individuals’ judgement and decision-making. We already know from previous chapters that we have a host of filters and lenses through which we interact with information, and these have evolved to produce evolutionarily advantageous outcomes, rather than accurate or ‘correct’ interpretations and beliefs. Cognitive biases are types of heuristics or shortcuts that make our thinking and decision-making faster and more efficient. Yet in many situations, it makes them also more error-prone. That is, we have heuristics and biases to make information processing and decision-making more effortless, not more accurate.

Unfortunately, this chapter is a little bit of a ‘listicle’ (trendy millennial term for an article that comes across as a mere list) because we’ve just spent a bunch of time looking at different types of informal fallacies, and now I want to cover some major cognitive biases. Like informal fallacies, these are often grouped in a range of different ways – a Google search will yield a host of lists purporting to contain ‘The 12 cognitive biases’, ‘The 10 cognitive biases’, or ‘The top 5 cognitive biases’. However, here I will cover a handful of biases that provide you with enough of a foundation to be able to spot others.

A foundational principle of cognitive therapy is that psychopathology (psychological illness) is produced by suboptimal information processing habits called cognitive distortions. ‘Cognitive bias’ is a technical term in cognitive clinical psychology (more commonly called ‘cognitive distortion’) used to refer to habitual ways of viewing the world and ourselves that exacerbate and prolong unpleasant emotions such as anxiety and depression. If you’re in a psychology program, you’ll come across this at some point. To avoid confusion, I’m using the term more broadly than it’s used in cognitive psychotherapy. You can read more about it in the article below[1].

One of the interesting things about cognitive biases (and something that’s a cognitive bias itself), is the fact that we have a very strong tendency to see these biases in other people, but rarely spot them in our own thinking. For this reason, try to be extra receptive to people who point out cognitive biases in your own thinking. Undoubtedly, if you’re a normal human being, you have a few that you may be blind to.

I’ll use a recent Psychology Today article[2] to narrow down the biases to include in this chapter.

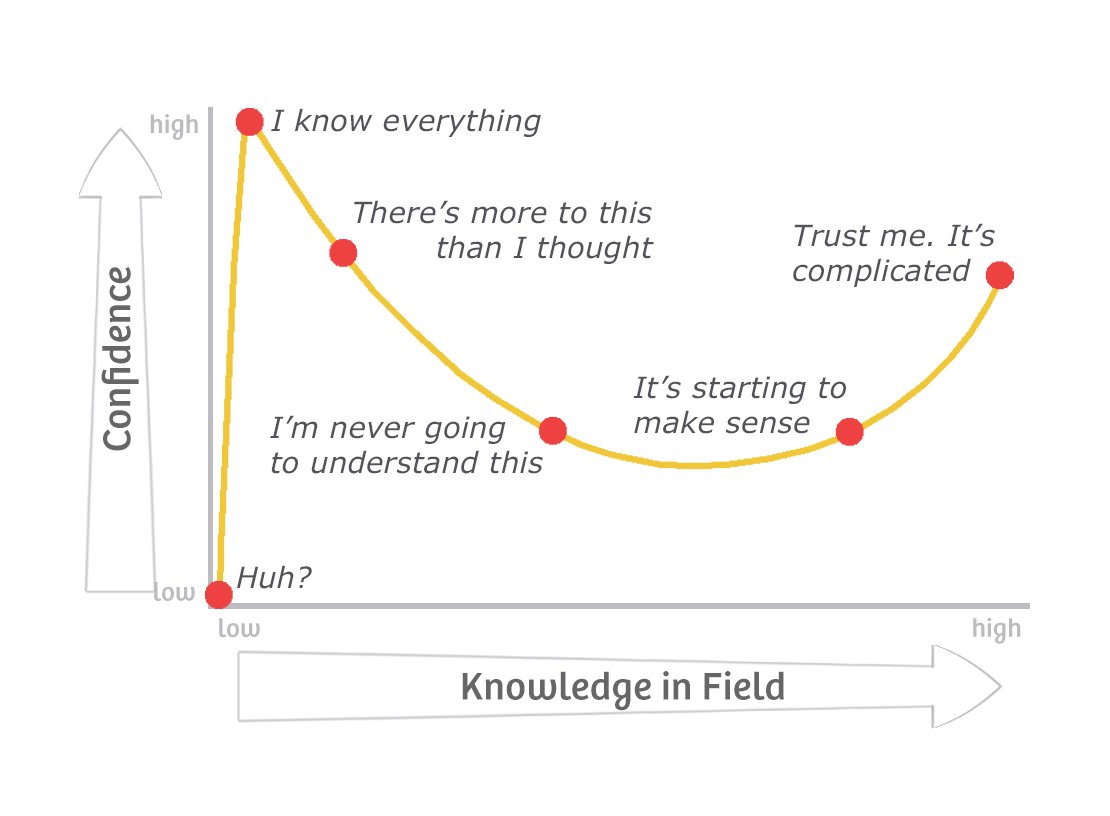

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

It’s an interesting fact that the more you know about a topic, the less confident you are in your knowledge. We’ve all come across this phenomenon, though you might not have known there was a name for it. The ‘Dunning-Kruger effect’ (Figure 7.19) is named after researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger (the original psychologists to formally describe this phenomenon) in their 1999 article ‘Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognising one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments’[3]. The bias is a case of the more ignorant you are, the more ignorant you’ll be of your ignorance. It’s often the people who know very little about a topic that have an unearned overconfidence in their knowledge of that topic. This is really a case of being too ignorant to even know how ignorant you are. Even Darwin wrote in the 1800s that ‘Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge’.

Confirmation Bias

This is our old friend from Chapter 3, so you already know a little about this one. I think confirmation bias is the most pernicious and pervasive of the biases, though this is just my opinion. We have an innate tendency to look for, favour, remember, and positively appraise information that supports a position we already have on a topic. We’re fixated on being right and are attached to our beliefs and positions because being wrong and changing our mind is uncomfortable and difficult. This has become a much bigger problem in the Information Age, where it’s incredibly easy to find evidence and reasons for just about any position imaginable. A simple Google search will yield all the confirming evidence and reasoning we could ever want, and therefore, protect us from ever having to change our mind – as long as we don’t mind actually being wrong. This bias doesn’t only protect us from having to confront falsifying evidence – we don’t even process and remember negative evidence in the same way. If you’re confronted with two pieces of evidence, one falsifying and one confirming your existing position, you’re likely to be much more critical of the falsifying evidence and less likely to remember it.

Self-Serving Bias

This bias is about our systematic tendency to look for different types of causes for events we interpret positively or negatively. Specifically, we’re less likely to blame ourselves for negative events as opposed to positive ones. As the name suggests, this bias does us great favours in boosting our self-esteem. To serve our need to maintain a positive self-image, we use filters for our experiences that blame external forces for the bad things that happen to us, and give ourselves personal credit for the good things. In this way, we see positive events as caused by things we identify with – like our character or behaviours – and we see negative events as caused by factors external to ourselves. There are so many everyday events that illustrate this. For example, following a car accident, both parties involved almost always blame the other driver. Research has shown that in cases of low self-esteem or depression, this common bias might actually be operating in reverse[4].

The Curse of Knowledge and Hindsight Bias

One downside to knowledge is that it makes you less likely to appreciate that others don’t know the same things as you. The curse of knowledge (sometimes called the ‘curse of expertise’) is one that many lecturers fall prey to. Some lecturers, who may have accumulated a great deal of knowledge in a specific domain, fail to consider the differences in knowledge between themselves and their students or even peers. This causes a range of issues, not only with communication, but it also makes it difficult to predict others’ behaviour. Once someone understands and integrates a new piece of information into their worldview, that information is now seemingly obvious.

Hindsight bias is similar, but refers to events rather than facts. Specifically, after an event has occurred (or is in hindsight), it’s so obvious that it would occur as it did, that it can be difficult to contemplate that it might not have happened this way. Once we have the certainty of hindsight, we seem to be able to convince ourselves that we could have predicted an event, and struggle to understand how ‘No one else could have seen that coming’. This happens when studying history sometimes, such as when we look at the build-up to World War I and wonder how it is that so many experts didn’t fully appreciate what was about to happen.

Optimism and Pessimism Bias

These are biases about probability. It’s certainly not a surprise that we have these issues since humans are innately terrible at probability (this explains why it’s one of the latest sciences to be developed). We have biases that predispose us to exaggerate our chances of succeeding, as well as failing. The difference can depend on who we are, what mood we’re in, the type of situation we’re thinking about, etc. The bottom line is that we’re terrible – and lazy – at properly thinking through the possibilities and probabilities of future events. For example, most university students surveyed believed their chances of being impacted by negative events such as divorce or having a drinking problem to be lower than that of other students[5]. Conversely, they believed their chances of experiencing positive events such as owning a home or living past 80 years to be higher than that of other students (confirmation bias makes it very easy to come up with supporting reasons for these beliefs). Optimism and pessimism about different events are not mutually exclusive. You may simultaneously hold some biases towards optimism and pessimism at the same time. Some people are also particularly prone to pessimism bias due to mental illnesses such as depression.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

A sunk cost is an expense that has already been incurred and can’t be recovered. The bias here is to view these costs as greater than future or prospective costs that might be incurred if one stays on the same trajectory. Consequently, when we’ve already invested something into a behaviour or endeavour, we’re more likely to continue to pursue it even when it becomes unprofitable to do so. For example, people sometimes order too much food and then overeat just to get their money’s worth. In this way, our decisions about how to behave are overly influenced by investments we’ve already made – the more we’ve invested, the harder it is to abandon course, even when it becomes woefully unprofitable to continue. We’re so attached the idea that we should get something in return for what we put in, that we’re almost hardwired to avoid ‘cutting our losses’, no matter how much these end up costing us in the long run.

Negativity Bias

We all know that we’re prone to keenly dislike negative emotions and events, but what you might not be aware of is that we weigh negativity greater than equally intense positivity. Our negativity bias is a natural propensity to attend to, learn from, and use negative information far more than positive information. In this way, not all emotions and experiences are given equal consideration. An obvious example of this is the amount of time and energy we spend fixating on an insult or a mistake, relative to the amount of time and energy we might spend on a comparable compliment or success. Negative events have a greater impact on our brains than positive ones. As a result, we register negative emotions and events more readily, and dwell on them longer. Negativity just ‘sticks’ more than positivity.

Note that this bias isn’t the same as the pessimism bias, which is about future events, not the impact of events that have already occurred.

The Backfire Effect

We all like to believe that when we’re confronted with new reasons and facts, we’re perfectly willing to change our opinions and beliefs. That is, you might have thought that was the case before reading this text or spending 5 minutes observing people on Twitter or Facebook. Well, things are even more dire than you may have expected. We’re so resistant to changing our minds that we have a fascinating ‘digging our heels in’ type of defence mechanism against new information and evidence. It’s as if changing our mind comes with such excruciating growing pains that we resist it at all costs – we’re even willing to trade-off rationality itself. Contrary to common sense (though probably not contrary to how you’ve seen people behave on social media), new facts and reasons don’t actually lead many people to change their minds, but can force them to become even more entrenched and double-down on beliefs as though they were bunkering down for a long wintery war. This is called the ‘backfire effect’ because sometimes showing people new evidence and reasoning against their beliefs actually causes them to become even more committed to them. Like a lot of the other biases I’ve mentioned, this one is easy to see in other people, but nearly impossible to notice in ourselves.

The Fundamental Attribution Error

This bias illustrates an imbalance in how we judge the causes of our own versus others’ behaviour. Relative to how we view our own behaviour, attribution bias leads us to overemphasise dispositional or personality-based explanations for behaviours observed in others, while underemphasising situational explanations. That is, the behaviour of others is a product of who they are, not the situation they’re in. For example, if we do something bad, we’re more likely to blame our circumstances than believe we’re ‘just bad people’. But when it comes to explaining bad behaviour in others, we’re much more likely to ignore the situational context and think their behaviour is more a product of who they are, not the circumstances they’re in. When we cut someone off in traffic, we rarely stop to think, ‘I guess I’m just a jerk’. Instead, we have a host of rationalisations that appeal to all sorts of circumstances, such as: ‘We just didn’t see the other driver’ or’ We were running late’. Conversely, if someone else cuts us off, we don’t grant them the time of day to even consider their circumstances that might be responsible because, of course, we know they’re just a jerk.

This bias is sometimes referred to as the ‘correspondence bias’ or ‘attribution effect’.

In-Group Bias

We often think of our world in terms of social categories or based on group membership (which is kind of a bias in itself – we just can’t help but view our world in terms of social groups). A by-product of these social categories is our tendency to have preferential attitudes and beliefs towards groups we consider ourselves to be part of. This bias is also commonly called ‘in-group favouritism’ since it’s the tendency to favour our own group (however we define it), its members, and characteristics more favourably than other groups. Now before you jump in with ‘That isn’t a bias!’, this is natural – of course our group is more favourable (think sporting team allegiances); otherwise we would simply change groups. This effect is so powerful that it’s even been shown to be influence people when they’re simply told they’re part of newly made-up groups that they know nothing about and minutes before didn’t even exist. This effect is so powerful that even when people are randomly allocated to meaningless groups, they almost immediately begin viewing their situation in group terms and showing in-group favouritism. This is another bias that’s good for our self-esteem, since we use our group memberships to shape our own identify and sense of self-worth.

The Forer Effect (aka The Barnum Effect)

This is a type of favourable self-referencing that leads us to think that vague and generic personality descriptions are overly specific to us. The easiest example of this is of people reading non-specific horoscopes describing personality characteristics of different star signs, and being more likely to see their own personality reflected in the description of their star sign. When this effect kicks in, we’re likely to see these types of vague descriptions as especially – or even uniquely – referring to us more than other people with the same sign. When we see ourselves in vague and generic descriptions that could apply to anyone (e.g. ‘strong’, ‘stubborn’), we’re falling prey to the Forer or Barnum effect.

A fun experiment to do with someone you know who is an avid horoscope believer is to tell them you’re of a different star sign than you really are. See how quickly they start to marry up your traits with what is supposedly true of that sign. When you reveal you’re of a different sign, they’ll probably just say, ‘Yeah, that sign is known for lying’. In this way, we can recruit confirmation bias and the backfire effect to ensure we’re safe and snug in our cherished beliefs.

Additional Resources

By scanning the QR code below or going to this YouTube channel, you can access a playlist of videos on critical thinking. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

By scanning the QR code below or going to this YouTube channel, you can access a playlist of videos on critical thinking. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

Further Reading and Video:

- Lecture on reasoning (the video is a bit hard to spot, but is at the top of the page):

Mikulak, A. (2012). The realities of reason. Observer. 25(2). https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/the-realities-of-reason - Cognitive biases: Busch, B. (2017, March 31). Cognitive biases can hold learning back – Here’s how to beat them. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/teacher-network/2017/mar/31/cognitive-biases-can-hold-learning-back-heres-how-to-beat-them

- Durlofsky, P. (2019, August 14). Why cognitive distortions worsen anxiety and depression. Main Line Today. https://mainlinetoday.com/life-style/why-cognitive-distortions-worsen-anxiety-and-depression/ ↵

- Dwyer, C. (2018, September 7). 12 common biases that affect how we make everyday decisions. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/thoughts-thinking/201809/12-common-biases-affect-how-we-make-everyday-decisions ↵

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognising one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121 ↵

- Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Burling, J., & Tibbs, K. (1992). Depression, self-focused attention, and the self-serving attributional bias. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(9), 959–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90129-D ↵

- Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 806–820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.806 ↵