Chapter 5. Language, Thought, and Concepts

Learning Objectives

- Understand the nature of language

- Understand the process and power of abstraction

- Understand how linguistic signs and symbols obtain meaning

- Understand the difference between semantic, syntactic, and pragmatic meaning

- Appreciate how language shapes our perception and experiences of the world

- Understand the power of concepts and their limitations

- Understand the role of scientific concepts and psychological constructs in shaping our worldviews

- Recognise the use of language as a rhetorical tool – especially the use of emotive and colloquial language.

New concepts to master

- Linguistics

- Semantic meaning

- Syntactic meaning

- Pragmatic meaning

- Reification

- Concepts

- Rhetorical

- Emotive language

- Colloquial language.

Chapter Orientation

Language deserves its own chapter in this book for many reasons. Language performs so many simultaneous functions in our lives and our thinking that go beyond just communication. We use language to communicate our status, specialist technical language polices class- or group-membership (people can tell I’m not a theoretical physicist by the types of terms I use), for entertainment (jokes, puns, musical lyrics, etc.), and to jostle for social position – social manoeuvring (you might show people you’re an authority on something by using obscure advanced language). Language positions us socially and is the primary device we use to manoeuvre through our interactions and relationships. Interactions are always transactional (there is always some exchange being made), and language is the means by which bargaining takes place. Primarily, the reason for a whole chapter on language is because it’s so central to thinking. Thinking and language are so intertwined that we simply couldn’t have one without the other.

Just because you can never get enough Wittgenstein, let’s allow him to set the tone for this chapter:

These inspirational quotes from one of the greatest of 20th century philosophers help us get a sense of the importance of language in understanding our world and our thinking. Wittgenstein was a cool character. His family was one of the wealthiest in all of Europe. He fought in the First World War and then turned his thinking to philosophical questions. After writing the only book of his life, a short 80-page pamphlet called the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1921, he declared that he had solved all of the problems of philosophy, gave away his family fortune, then retired and went to work as a gardener in a monastery (this didn’t last though, and he came back to philosophy later in life).

Language is how we understand the world and ourselves. Words are the lyrics of our lives, and just like songs and poems, our lives have very little meaning and significance without the words we use to fill them. Language is the form of all of our thinking. In the same way a computer stores and processes information in binary units (that is, as 0s and 1s), our thinking and understanding is composed of units of words and linguistic symbols. That means what we can think, what we do think, and what we can understand and know about the world is entirely dependent on language. This is why Wittgenstein asserts that the limits of our language are the limits of our world. The limits of our vocabulary place limits on our thinking, understanding, experiences, and social power. There’s no way to overestimate the power of language. We can’t perceive, understand, or interact with things until we have the capacity to symbolically represent them in thought – and this symbolic representation is the very nature and purpose of language itself.

Language and words are the very substance and vehicles of thought – words are how and what we think. Therefore, any course on thinking that doesn’t focus on language hasn’t understood or addressed the heart of thinking at all. This chapter will focus on two areas where understanding language is important for critical thinking: how language influences what and how we think, and how language is used as a rhetorical tool to be persuasive.

This chapter’s content touches again on topics from Chapter 3 about sensation, perception, and beliefs, as well as Chapter 4 about knowledge because – as you might be able to anticipate – it’s through language that we represent the world (that is, our worldview, models, and beliefs are linguistic things made up of words and concepts). Therefore, concepts and language serve as another top-down influence on our sensation and perception. Secondly, language is the medium or material of our thought and knowledge – in the same way we build houses out of bricks, we build our knowledge and thoughts from words and linguistic symbols. Without language, thought and knowledge wouldn’t be possible.

‘Linguistics’ is the scientific study of language and communication.

Let’s review the last chapter’s content.

Chapter 4 Review

The last chapter was concerned with how knowledge is constructed. We started off with one of the first-ever definitions of knowledge, provided by Plato, who described it as ‘justified true belief’. This account of knowledge provides three criteria that are jointly necessary for something to qualify as knowledge: the individual claiming knowledge must believe it, there must be some justification, and the claim actually has to be true. However, it turns out that satisfying these conditions is much more difficult than you might expect.

Despite belief being one of the three prongs of Plato’s description, the distinction between mere belief and knowledge remains very important. We can, and often do, believe many things that don’t qualify as knowledge because either they’re not true, or we don’t have any justification for them.

The major headaches arising from these criteria is owing to problems with the ‘J’ in the formula (or the justification). Just how do we go about justifying claims to knowledge? There are a number of ways we use the term ‘knowledge’, and we were able to distinguish between three main ones: (1) procedural knowledge, (2) acquaintance knowledge, and (3) propositional knowledge, which concerns us in our interactions with the world (and is the focus of our critical thinking journey).

The best way to formulate and appraise claims to knowledge is by representing them and unpacking them as arguments. Therefore, a knowledge claim is nothing more than a proposition or assertion about the world which rests on a series of other propositions that serve as its premises in order to justify it (a proposition offered without supporting premises is an unsupported assumption). The idea of an unsupported assumption can be tricky – especially when the proposition might seem true. But whether a proposition is true or not is irrelevant in deciding whether it’s an unsupported assumption. The only thing that counts is whether the person presenting it offers supporting evidence and reasoning for it.

One useful distinction when understanding knowledge is between what’s called analytic and synthetic types of knowledge. Analytic propositions and knowledge are concerned with language and the meaning of terms, and therefore, can be justified through an analysis of language and definitions. Conversely, synthetic propositions and knowledge involve ‘matters of fact’ or events and objects in the world, and therefore, are justified through empirical evidence.

In this way, we learned that different types of knowledge (such as analytic versus synthetic) require different types of justification. For analytic propositions, justification is more straightforward, and we can even achieve something like the necessity, universality, and certainty that Plato believed was the real meaning of knowledge (fought for by the Gods in his myth). This is because when it comes to analytic propositions, we can have some certainty about the meaning of the terms and no empirical evidence is required. For example, to justify the proposition ‘All bachelors are unmarried’ requires nothing more than unambiguous use of the terms ‘bachelors’ and ‘unmarried’.

Synthetic propositions can sometimes be elevated to the status of facts once we believe there’s sufficient justification for them. We learned that a ‘fact’ is something we’re confident is ‘the case’ or is a state of affairs that has been provided with sufficient justification. In this way, ‘fact’ is a type of success term, in that a claim graduates to being considered factual only when we believe sufficient justification has been provided. In contrast, a proposition we believe is a good candidate for a fact, but hasn’t yet received justification, is called a hypothesis or a conjecture. Hypotheses are propositions that are awaiting testing and evidence.

The difference between analytic and synthetic knowledge also takes us back into our earlier discussions about the use of deductive and inductive reasoning. We learned that justification isn’t an all-or-nothing type of status, but should be thought of as existing along a continuum that has ‘certain’ at one end and ‘unlikely’ at the other. To achieve ‘certainty’, sound deductive reasoning is required, while inductive reasoning only provides us with ‘probable,’ ‘plausible,’ ‘possible,’ and ‘unlikely’ knowledge. I showed how deductive reasoning fits nicely with analytic propositions, and pointed out that synthetic propositions (those that are about the world) almost always require inductive reasoning.

The downside of achieving certainty about analytic knowledge through deductive arguments is that they’re merely ‘explicative’, which means they tease out or unpack (i.e. explicate) the meanings of the terms without going beyond them (that is, beyond the premises, which are largely definitional) to any new knowledge or information. Inductive arguments, on the other hand, can go beyond mere meaning and definitional premises to new knowledge. This is why we call them ampliative – because they amplify our knowledge. Note that inductive reasoning is sometimes even called ampliative reasoning. In order to be ampliative and progress knowledge, inductive arguments must trade off the certainty of deduction, and venture into unknown territory by accumulating specific premises that incorporate empirical evidence to support uncertain conclusions.

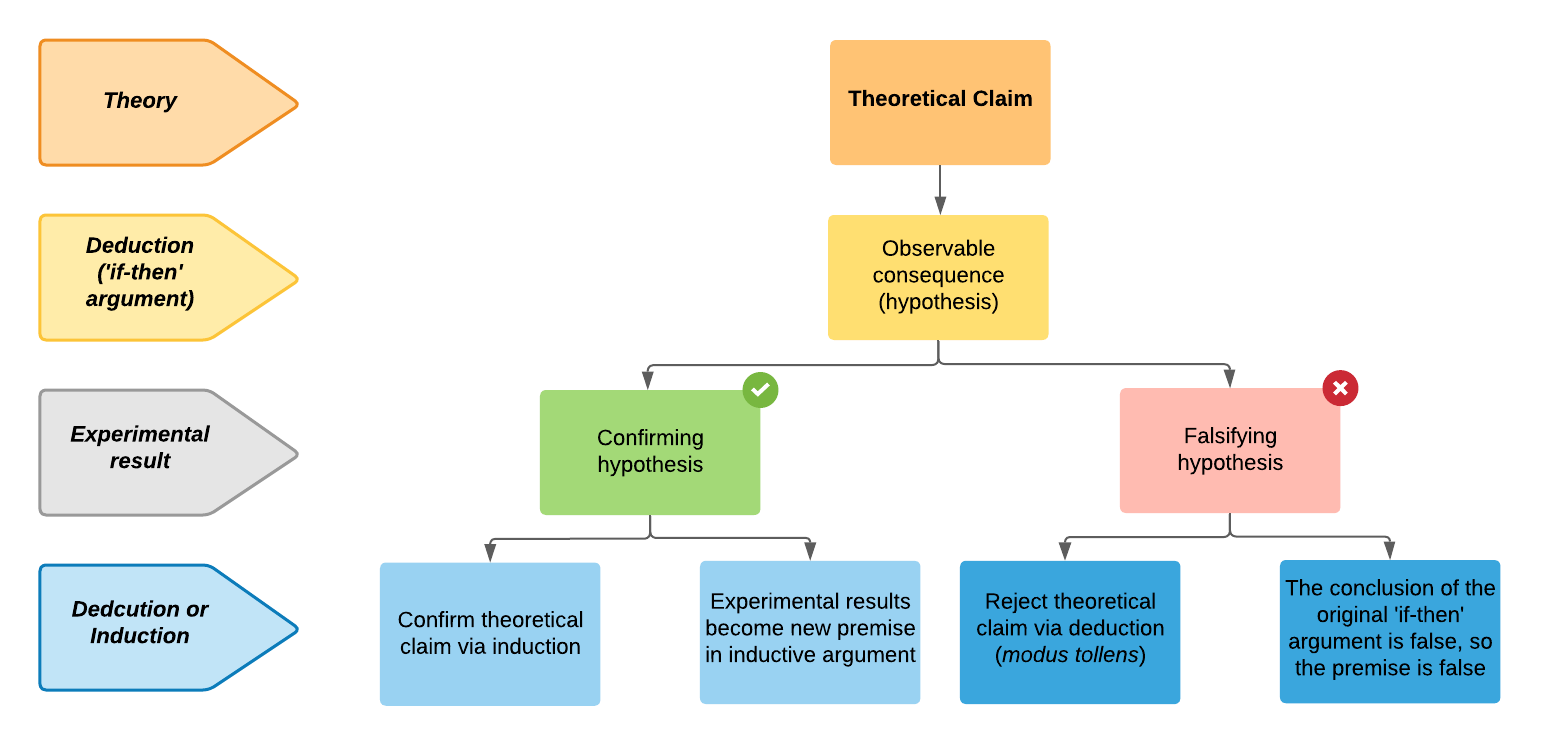

Next, we identified the uses of inductive and deductive reasoning in scientific practice. At different stages, science relies on both induction and deduction. Deduction is used when we go from theoretical claims (‘Childhood trauma increases the chances of experiencing adult psychological illness’) and deduce observable testable hypotheses from them (‘A sample of mentally unwell adults should have higher rates of childhood trauma than a similar sample of mentally healthy adults’). In this way, we use deduction to determine the observable consequences of a theoretical claim. To achieve this, we simply ask ourselves, ‘If the theoretical claim is true, what should we observe?’. To continue the example, the reasoning is ‘If childhood trauma increases the chances of experiencing adult psychological illness’, then we should observe that ‘A sample of mentally unwell adults should have higher rates of childhood trauma than a similar sample of mentally well adults’, which becomes our hypothesis. We’ll learn more about this conditional ‘if/then’ type of argument later in Chapter 6B.

The next step is to conduct the study and make the observations that test this hypothesis we’ve deduced. We then employ either deductive or inductive reasoning pending the results of our study. If the result of our study falsifies the hypothesis, then we only need to use deductive reasoning to reject the theoretical claim. Consequently, assuming there are no flaws in our study, and we observe that rates of childhood trauma among mentally unwell adults is the same as – or even less than – mentally well adults, then we’ve falsified our hypothesis. In this way, the observable hypothesis serves as the conclusion of a deductive argument with the theoretical claim (‘Childhood trauma increases the chances of experiencing adult psychological illness’) as the premise, and when the conclusion of an argument turns out to be false, we have either an invalid inference or false premises. In this case, the inference is sound, so the theoretical claim represented by the premise is falsified.

However, when the study confirms or corroborates the hypothesis, we rely on inductive reasoning, and that’s a big part of the reason why confirmation of hypothesis is cheap and unconvincing in a lot of cases. Because a true conclusion (the hypothesis being confirmed) doesn’t mean premises are true, the argument has to be reformulated, so the true conclusion becomes a new empirical premise in an inductive argument that’s believed to support the theoretical claim. These steps in scientific reasoning are summarised in Figure 5.1.

So why all this fuss? Well, a lot of energy has gone into tackling problems of knowledge and justification – especially as they relate to scientific work – and it’s easy to start to feel as though the pay-off may not be sufficient. But scientists and philosophers believe this investment of time and energy into tackling these problems is worthwhile due to the great power that knowledge affords us. Remember the quote from Francis Bacon: that knowledge itself is power. Belief is only ever accidentally powerful, so it’s worth trying to work through these issues to ensure what we believe counts as knowledge. Therefore, we can influence the world in ways that are consistent with our values.

What is Language?

We almost always start our chapters with the most basic question, and that’s invariably a ‘What is?’ type of question. As we learned in Chapter 2, sorting out what we mean by our key terms is a precondition to being able to have any sensible and fruitful discussion. So we start the meat of our fifth chapter by asking, ‘What is language?’. As with all our beginning questions, this misleadingly simple one hides some very complex issues that only become apparent with further penetrating questions. Like a lot of concepts in this text, language is something we use every day and mostly take for granted, without realising. And it’s fraught with a number of complex landmines.

Let me provide a definition and we’ll work from there.

Language: Language is an organised, rule-governed system of abstract and arbitrary symbols that are agreed upon by a community of people to represent and reference (or point to) specific things we want to think or communicate about (including both our internal psychological world, as well as the outside world).

Language affords us the ability to represent abstractly, which is responsible for the two great achievements of human cognitive evolution: thinking and communicating.

A couple of ideas should immediately stand out from this explanation:

- Language is so powerful because it’s an abstraction to the symbolic, which means it replaces the real things in the world with a set of arbitrary symbols. This allows us to manipulate the symbols and do a lot of the heavy lifting of thinking, which would be impossible if we didn’t have the flexibility and utility of symbols. For example, we can mentally work out how to divide 10 apples evenly between 2 people without needing the actual apples. Symbols allow us to create, change, add and subtract, move, exchange, contemplate, and manipulate meanings and ideas that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. Symbolic representations also allow us to think of things that aren’t concretely available in our immediate experience. You can easily think of apples or numbers – or any number of ideas – using their symbolic representations.

- In this way, thinking is possible because of language.

- The symbols that make up any language only have meaning due to conventional (i.e. interpersonal and social) agreements, which just means the abstract symbols are tied to the concrete referents (objects such as apples) only because all of us agree to interpret them in that way. We can speak to each other of apples because we all agree that the symbol – or word – ‘apple’ points specifically to these objects.

- In this way, communication is possible because of language.

Language is a game – or system – of symbols. Like other games such as those with playing cards, these symbols (i.e. numbers and suits) form concepts and ideas and combine to represent things we want to think about, experience, and communicate. Linguistic symbols create distinctions for us and pinpoint distinctions that are considered meaningful by our language community. For example, the meaning of the ace of clubs isn’t the same as the nine of hearts. Meanings are also game-dependent or context-dependent, just like language. That is, an ace of clubs might serve different purposes whether we’re playing blackjack or poker. The system of symbols within a game also influences what we take as not being meaningful, such as differences in the design on the back of cards. We might combine a deck of cards so that half have plain-coloured backs, and half have a landscape picture on the back without influencing how the cards are used.

Since language provides the tools that make thinking and communicating possible, it’s no surprise that these tools in turn influence and place limits on what thinking and communication are, or how they happen. If thinking is the manipulation of symbols, and communication is the sharing of these symbols, then it’s the nature of the symbols themselves that shape and limit our thinking and communicating. Therefore, it’s the outer limits of our symbolic toolset that enforce limits on our thinking, our communicating, and even what we can experience (Wittgenstein put it more poetically in the quote from the start of the chapter). You simply can’t have a thought, or communicate something, or even fully experience something that you don’t have any way of symbolically representing. You can certainly experience it in a raw, immediate sense, but not fully, and certainly not contemplate the experience in any meaningful way. Those rare experiences that we have, which we don’t have language for are often felt with great uncertainty and apprehension due to our inability to process them cognitively. This isn’t that different to saying ‘The limits of my toolbox are the limits to the repairs I can do around my home’, and in fact, the limits to your toolbox and repair skills are the limits to all the repairs you could even conceive of or imagine. Consequently, language grants us enormous power, but does so at the cost of confining us within the boundaries of its symbols.

Explanation Sidebar – ‘Concepts’ and ‘categories’: Students often struggle with the notion that language directly shapes and filters the types of experiences we can have. Without language, we don’t have concepts or categories to encode and understand our experiences. For this reason, we instinctively, and even unconsciously avoid or suppress experiences that we don’t have language with which to represent, understand, and process. Without symbolic representations to process experiences with, we’re lost adrift in a sea of bewilderment without a linguistic lifeboat to hold on to or mentally work with. Without symbolic representation to think with, experiences are a mere shadow of what they could be and tend to provoke anxiety or discomfort in us. We need handles to grab on to things and words are those handles. Experiences, without concepts to make sense of them, are felt as shallow and disconcerting, and leave us scrambling to locate some rational or even supernatural explanation for them. Without words and concepts, our experiences have no reflective depth.

Our concepts provide us with analytic or interpretative categories that we can organise things into. These linguistic categories give us a greater understanding of the thing we’re thinking about. Organising our experiences into categories tells us more about the thing than we’d otherwise know. Knowing the concept ‘poodle’ belongs to the category ‘dog’ or ‘pet’ tells us a lot more than the concept ‘poodle’ alone.

Understanding that our concepts and categories are our only way of understanding anything, and our understanding is limited by the precision and clarity of our concepts, we begin to appreciate that to learn to think and understand anything is a matter of collecting new concepts and categories. For example, our worldview is constrained by our available store of concepts, which then dictate the type and form of world we perceive and experience.

People with very strong attachments to certain concepts can’t help experiencing the world according to these concepts. Consider people for whom ‘race’ or ‘caste’ are core concepts. Their experiences of everyday activities like buying lunch will be experienced through these lenses. These concepts will ensure they have different experiences than other people for whom something like race is an interesting – though very minor – categorisation. For example, social caste (which is something like biologically determined social class) is an unfortunate social reality for people in India. There are certain individuals who experience and interact with their world exclusively in terms of caste and will even forgo food for many days if there is no one of the appropriate caste to prepare it for them. These concepts create and facilitate experiences for these people that might seem impossible for someone of European heritage born and raised in Australia. This is also why it’s so important to constantly interrogate the usefulness of our concepts.

The power of categories and concepts are often self-evident to those who hold on to them, but they can look silly and even dangerous to outsiders. This is part of the dangers of reification, which we’ll talk about soon. For example, the reification of caste in India, or of race differences in South Africa has resulted in untold suffering and violence.

Concepts are like mini models – they’re exceptionally powerful and even comforting, but they can be enslaving. Once an experience or idea is tethered or anchored in concepts, it becomes rigid and nearly impossible to shake-off because all our new experiences will be interpreted through the lens of this concept, and therefore, won’t be able to falsify the concept (show that it doesn’t fit or serve its purpose). When everything is bent into shape to fit our core concepts, nothing will be able to show how the concept doesn’t actually fit our experiences.

When you learn new concepts, you’re expanding your toolbox for thinking and even opening yourself up to new experiences. Let me illustrate with a concept from this text. Prior to reading this text, you might not have had much familiarity with the concept of a logical fallacy. Since reading these chapters, you’re likely to now have picked up a lot of information about this concept, what it means, what it refers to, and how to apply it. Therefore, while previously you had experiences of fallacious reasoning in a vague sense – that certain arguments or premises were inadequate – your experience of fallacies wasn’t very sophisticated or complete. Now you’ve learned this new language of logic and fallacies, you can have a range of new experiences and understanding of the world around you. In this way, all your learning from this text is actually a matter of learning a new language. And whenever you learn a new language like this, you expand your horizons and the kinds of things you can think about, experience, and communicate.

Another example from psychology will be useful here. When you don’t have training in psychology, you’ll have a rudimentary and crude understanding – and possibly, experience – of mental illness, but you won’t be able to fully grasp it in a complete way. Learning a framework and conceptualisation like the one provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (or DSM) gives you a new language with which to understand and think about these phenomena. By learning this new language, you’ll have a sophisticated conceptual category system that provides labels and groupings of mental illnesses according to theoretical frameworks. In this way, you’re learning a new language that allows you to think about, experience, contemplate, and communicate about mental illness in more depth. Without the conceptual category system like the DSM, you’ll fumble through by merely grasping at vague senses of what mental illness are all about without any way to do any serious thinking about them. This also helps explain the second quote from Wittgenstein that we began our chapter with, ‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent’. Which is to say, without a language and set of concepts to make sense of our experience, we can’t speak or think about things properly and are forced into an impotent, confused silence.

From these examples, you can appreciate how our language is just the store of concepts we have available to think and speak (test this out by trying to say something without the use of concepts). But as I also illustrated in the example of caste (in the Explanation Sidebar above), words and concepts create our understanding, and also get in the way of it. Concepts and categories are bindings that shine light and give us understanding, but lock out other possible interpretations. Yet concepts, as our own constructions, are never perfect fits, and like models, they’re only approximations. We encounter problems because we become hypnotised by concepts and can’t seem to get rid of useless ones or see the world without them.

Symbols and Abstractions

Let’s delve a little deeper into this idea of symbolisation and abstraction. The word abstract means something like to ‘remove’ or ‘detach’. Therefore, to abstract is to step back from, or move away from a concrete thing in order to represent it, or part of it. Something that’s abstract usually exists as a representation or idea rather than in a concrete, real sense. Like how a painting of an apple – or even the word ‘apple’ – is an abstraction, while the real apple is the concrete thing. Signs and symbols that represent the idea are also arbitrary because they could be exchanged at any time – there is no necessary connection between the abstract linguistic symbol and the concrete thing being symbolised.

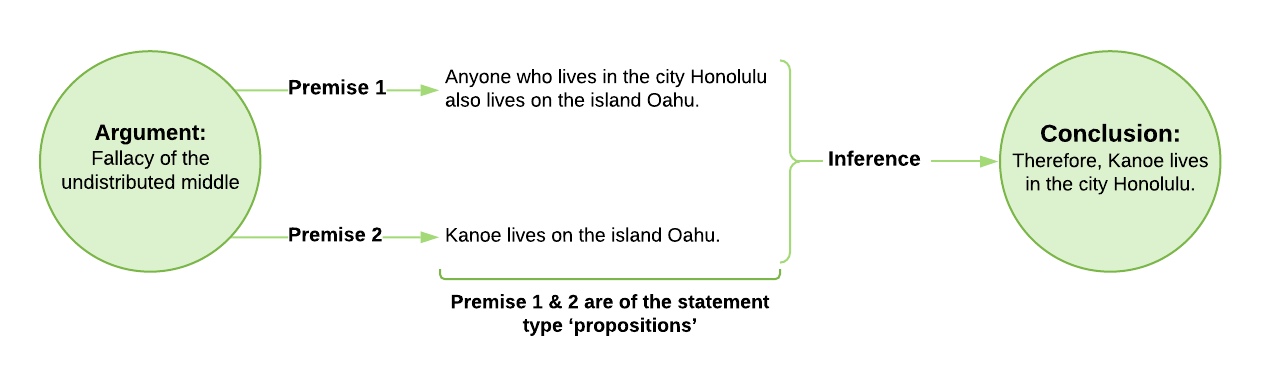

The process of abstraction that gives us language replaces concrete things with symbols that are taken to represent them and replace them in our thinking. Symbols are simply signs in the form of written or spoken words (or anything, really, if the relevant community agrees to accept the sign), that refer or point to the thing being represented. I alluded to part of the power of language above as owing to its symbolic nature when talking about how much flexibility this affords us. Symbols are super lightweight and can be manipulated in an almost infinite number of ways. The example above of being able to manipulate quantities in our head using number symbols is perhaps one of the easiest for us to understand. But logic works this way as well, and we’ve been learning a lot about this in this text. Take the following example logical argument:

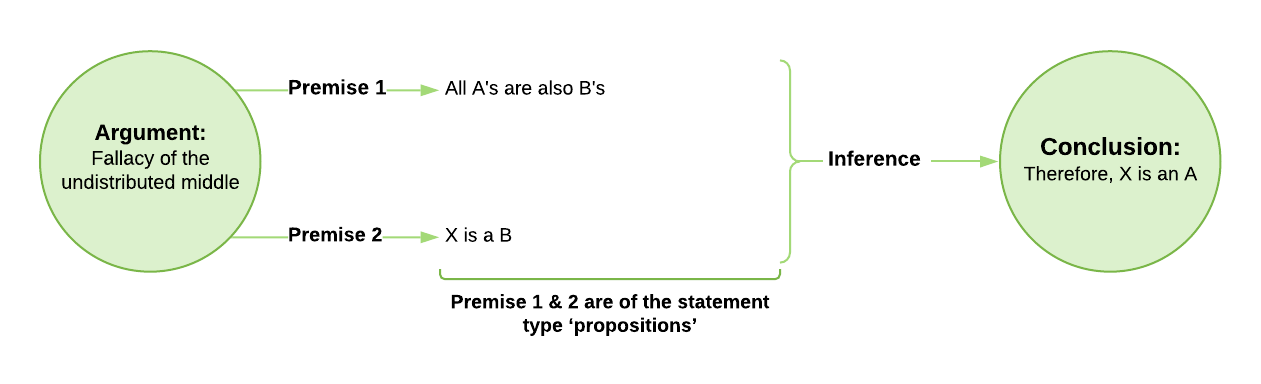

The first thing you should notice is that we’re not dealing with the concrete here, which means we’re not looking at where Kanoe or the city of Honolulu is to understand the propositions. By dealing with symbols, we can process this information and make judgements about it using only the signs themselves. But we can go to an even greater level of abstraction and use letters to symbolise the objects in the propositions, and this sometimes helps us appraise arguments even more. Let’s see what this looks like:

We might be able to get a better look at this argument when abstracted even further to symbols like this. Another powerful tool with abstractions is sometimes to switch them out for another set of words (i.e. symbols), and in that way, get a different angle and understanding of the propositions and arguments (in this case we can get a better sense of why this argument is invalid and absurd by using different words). See below when I change out the As, Bs, and Xs for something else.

By switching out symbols – which is a possibility only because we’re dealing with abstract signs and not the concrete things themselves – we see how this argument is invalid (because true premises lead to a false conclusion). Without the flexibility that an abstract system of signs (i.e. a language) offers us, we couldn’t manipulate the propositions in this way to dig in to them and understand the argument more deeply.

In Chapter 3, we learned that the mental models we use to navigate the world are abstractions because they detach or extract certain features of the real world, while eliminating unimportant details. Language does the same thing, but in a more general sense. A major function of language is that it’s capable of modelling specific things in the world, as well as the relationships among these things, via statements and propositions.

This abstracting power of language comes at an enormous price: it’s forever disconnected from things the signs point to, but this gives us several thinking superpowers. We can think about things we’re not immediately experiencing such as people, places, and objects or anything that we may have no contact with, but a word to symbolise. Even more remarkably, we can think of things we’ve never had – or could never have – any concrete experience of, such as abstract concepts (e.g. a perfect circle or infinity) or fantasy objects (e.g. ET or Santa Claus). Through the powerful use of language to abstract and communicate, we can even think about and experience things that have only happened to other people – which is a powerful therapeutic tool for those of you considering a clinical career.

Varieties of Meaning

A natural question from learning all this is to wonder how it is that symbols get – and hold on to – their meanings. I alluded to this above when I referred to the social and interpersonal nature of language –signs hold meanings for us just because we all agree on them. We learn them in school and rarely need to question them until they fail us. Therefore, we inherit these meanings in a way and reinforce them by practice in the community. In this way, you could change meanings if you really wanted to, as long as you aren’t too concerned with being understood by anyone else. This is why words have no objectively correct definition (recall this point from Chapter 2) because the meaning is merely a consensus decision on the part of the community of people using it. Consequently, the definitions are subjective (a social-level subjectivity, though, rather than individually subjective) because we can’t personally have our own usable definitions. Only a community of people can have its own subjective definitions that change and mutate with use (which is why dictionaries update every year to change the meanings of words or add new ones).

Because the meanings of words aren’t fixed, but are achieved through ongoing negotiation within interactions by the group of people using the language, words are incredibly slippery things prone to mutate and shape-shift right in front of our eyes – even mid-discussion – without anyone intending it.

Another important feature of language is also quite counterintuitive. Language is only internally meaningful since it’s self-referential (don’t worry, I’ll unpack this). Despite how we intuitively think of language, the signs and symbols don’t actually point to things outside the language, but to other signs and symbols inside the language system. This is because symbols can only point to other symbols and not to real or concrete things. In this way, they’re only internally meaningful because their meaning is derived from their role within the whole system and doesn’t require a concrete link to anything outside the system. This vague point will be easier to understand with an example. The word ‘tree’ isn’t connected to an actual tree. If it was, it wouldn’t be very meaningful as it would be too rigidly tied to referring only to that tree and not to any other tree, or to all trees for that matter. Rather, it’s meaningful because it points to other signs and symbols in the language system. Hence, it’s self-referential, since the system of symbols points only to other parts of itself. In this way, individual signs and symbols don’t have meanings in isolation, but only as part of the whole system of language. Consequently, words as signs can’t be defined by pointing to things and saying, ‘Tree is this’. Though you can use it as an example and say, ‘Things like this’, just having to say the extra words shows you’re recruiting extra signs and symbols to communicate the meaning of the word, and merely pointing to the tree is a helpful aid to your definition. Some words like ‘bark’ copy features of the thing being referred to – the actual sound of a bark is similar to the sound made when speaking the word, but without further explanation and elaboration, you can’t hope a non-English speaker will know what ‘bark’ means if you say it in isolation. Another way to appreciate that words have meaning only because of their connection to other words is by opening a dictionary and observing that the only way meanings of words can be described is with other words.

The signs of language possess meaning in several ways. Individual words have meaning based on their use in sentences, their associations with other words, and their outcomes (what they’re used to achieve). The meaning that’s achieved by the role of words inside sentences and by the use of words to achieve outcomes is referred to as syntactic and pragmatic meaning, respectively (we’ll discuss those soon). The nature of the meaning of words is also a product of their association with other words. In this way, word meanings are holistic, just like beliefs (as we saw in Chapter 3). This type of holism suggests that word meanings are achieved by a network of connections between words including their synonyms (words with overlapping meanings) and antonyms (words with opposite meanings). For this reason, the word ‘pig’ has a variety of meanings, and these are derived from its links to other words like ‘tasty’ (at least for me, personally), ‘cute’, ‘fat’, ‘dirty’, ‘loud’, etc.

One important thing to note is that in everyday language use, meaning is more often ‘sentence-sized’ than ‘word-sized’. Therefore, meaning exists at different levels – or pieces – of language; from the most basic level, which is individual ‘words’ and ‘sounds’ (the individual signs), up to phrases and sentences (or combinations of signs), to even larger units, such as discourses or conversations. Each of these levels influences the meaning of what is being thought about or communicated. For example, words change meanings depending on which sentence they’re used in and which context or conversation they’re part of.

In everyday life and in science, meaning is understood and expressed more in the form of statements than individual words. That is to say, useful meanings operate at the ‘statement level’ more so than the ‘individual word level’. Similar to saying the meaning of a house isn’t each individual brick, which on its own doesn’t quite represent a house. While individual words have their own meanings (of course), the meanings that serve us most in thinking and communicating are statements, and as we’ve seen many times in this textbook, the statements that are of most interest for critical thinking and scientists are propositions (analytic, synthetic, and normative). Therefore, when appraising the meaning of propositions, think more about what the specific words mean in the context of the proposition, rather than simply the dictionary definition.

In fact, the role of individual words in sentences and propositions is part of how words get their meaning, so there is another type of cyclical influence here. The meaning of individual words (called their semantic meaning), when combined, create the meaning of sentences (which provide syntactic and pragmatic meanings), but the role of words within a sentence is partly how the words have any meaning at all.

We defined the technical term semantics as the study of meaning back in Chapter 2, but in this chapter, we’ve introduced some related words that need to be defined.

‘Syntactic’: Syntax is the set of rules or principles that govern how words and phrases are put together to form sentences. You all know a lot of syntax – possibly without even knowing that this is the term for it. Therefore, syntax tells us the possible and appropriate format and structure of sentences. A lot of the grammar you learned in school is concerned with syntax.

So the placing and pattern of words and phrases within a sentence is part of how those words and phrases actually possess meaning.

‘Pragmatic’: Pragmatic is sometimes used as a synonym for ‘practical’, which gives some sense of what it’s concerned with. Pragmatics is concerned with practical or even sensible uses of something. Pragmatic considerations only worry about the outcomes or effects of something. A pragmatic view of something is an instrumental view – that is, what does it do that’s worthwhile or useful?

So the use of a word or sentence is another part of how words and phrases possess meaning. The meaning of a sign according to a purely pragmatic viewpoint is nothing more than how it’s used. According to this pragmatic account, words mean whatever it’s you can do with them.

Varieties of Influence

Language doesn’t merely express meaning and ideas, but plays an active role in shaping them. There is quite a bit of controversy as to the amount of influence language has on our thoughts and experiences. Generally, the idea that language influences our thoughts and experiences is called linguistic relativism, and like most philosophical positions, this comes in strong and weak forms. The strong form is called linguistic determinism, which claims that language ‘determines’ thinking in an absolute way. Linguistic determinism further claims that society itself is confined by its language. This has been called the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis because it was championed most influentially by the linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf (though they didn’t come up with the notion on their own). Earlier in the twentieth century, Sapir wrote:

Human beings do not live in the objective world alone, nor alone in the world of social activity as ordinarily understood, but are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression for their society.[1]

Whorf further claimed:

We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages […] We cut nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do, largely because we are parties to an agreement to organize it in this way — an agreement that holds throughout our speech community and is codified in the patterns of our language.[2]

In this way, language predetermines what we see in the world around us. We can take an example from science that Sapir and Whorf introduced. The Hopi language (Uto-Aztecan language) doesn’t include any concept of time seen as a dimension, and so Whorf hypothesised that, without this conceptual tool, a system of physics developed by Hopi speakers would be radically different from the mainstream physics of today. Whorf suggested that a Hopi physicist and an English physicist would find it virtually impossible to understand each another.

The weaker – and more justifiable – form of linguistic relativism is just referred to as linguistic influence, and, as the name implies, claims that language influences rather than determines thoughts, experiences, and our worldview. A research experiment illustrates this. The language of an Amazonian tribe called Pirahã lacks terms for quantities greater than 3. When tested, members of this tribe made errors in recognising and thinking about quantities of things without having terms available to represent them (that’s without having terms for the numbers 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and so on). For this tribe, the challenge isn’t one of simply being unable to count. Without conceptual representations of these quantities, they were unable to think in this way and discriminate between quantities they had no notion of. Their ability to count wasn’t in question, for the numbers they had concepts for – they could count just fine. This experiment shows how our language shapes our ability to experience, think about, and recognise things in our environment.[3] As I mentioned in Chapter 1, learning new terms and concepts is like gaining new thinking powers.

The main point here is that words are not merely passive labels that are applied to things, but have a role in influencing perception and thought. This might seem like a strange idea at first, but let’s look at two particular influences – those of perception and belief.

Language and Perception

We already know from Chapter 3 that how we think influences our perception, and that this is one of the important top-down influences we have to deal with. Given that thought is shaped by language itself, it isn’t much of a stretch to realise that language also shapes our perceptions. I also alluded to this above when we talked about how dependent our experiences are on us having a language we can use to think and communicate. This extends to perceptual experiences. At a fundamental level, the language we have with which to recognise and process experiences influences what we pay attention to, how much attention we give to things in our perceptual field, what importance we attribute to these things, and what subsequent thoughts we have about them. These variations account for important differences in the worldviews of people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, but even among English speakers, there are important effects on perception that are a result of having linguistic categories (i.e. words) to organise experiences into.

Language may not necessarily create perceptions, but rather acts as a filter, enhancer, or framer of perception and thought. While people of differing languages have the same building blocks of sensation at their disposal, it isn’t simply the case that people in different linguistic groups all have the same experiences under different names. As Sapir (who as I mentioned earlier, was one of the most influential American linguists) wrote: ‘The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same worlds with different labels attached’.[4] As you can imagine, this is quite a controversial issue, but more and more research is being done and is revealing a number of important influences of language on perception.

One basic area of research is in colour perception. Russian people have different words for light and dark blue, and so when asked to discriminate between different colours in a cognitive experience, native Russian speakers are faster at detecting the difference between these blues than similarly different shades of grey.

Language and Belief

You’ll remember from Chapter 3 that a belief is a personal position we adopt towards claims whereby we accept them as being accurate or factual, and that beliefs relate to propositions. So if beliefs are propositions or statements, then this means they’re also linguistic things – that is, things that are made up of words. Thus, a belief is a linguistic thing. It might be thought of as an emotional conviction attached to a concept.

Knowing that beliefs are built up out of language in the same way that water is made up of hydrogen and oxygen atoms, allows us to understand better the powerful influence that language has on our beliefs. In the same way that the material our clothes are made from influences how they look, function, and fit, the nature of the words and sentences that form our beliefs influence the nature of these beliefs.

An obvious limitation imposed by the linguistic nature of beliefs is on the things we can have beliefs about. You simply can’t have beliefs or even think about things you don’t have any words for. The meaning of the words and the propositions that your beliefs are made up of influence the character of these beliefs. In a similar way that our beliefs are structured holistically or as a web, the meaning of words and propositions are tied closely to a web of other words and propositions. I realise I already mentioned this above, but I want to make the point that the meaning of our beliefs is tied closely (and even constrained) to the meaning of other words and propositions in our belief system. For this reason, the meaning of our words and our beliefs are co-dependent on each other. In this way, the kinds of beliefs we have are dependent on the meanings of the words that make up the propositions, as well as how these meanings and propositions tie together into larger webs of belief.

This helps explain why we’re sometimes so resistant to off-loading beliefs that aren’t true or are no longer useful. Even if we aren’t attached to a specific belief that needs to be off-loaded, we can resist giving it up if it connects to a set of important meanings for a number of other beliefs and terms in our worldview. A specific belief we hold might be core to understanding the very meaning of certain terms, so the belief plays an important role in our worldview, and therefore, is more resilient against falsification.

A change of worldview or even religion is something like a change of concepts or a change in language. It’s nothing more than the shift of allegiance to specific concepts.

More on the Centrality of Concepts

We’ve already touched on concepts many times, so you’ll already have some appreciation of their role and influence. The influence of concepts may be more far-reaching than you would expect. It’s not overhyping to say that we live conceptually. Our self is a concept that interacts with other things only as concepts. This means, what we call our ‘self’ is really just a set of ideas and representations that we hold mentally. This self-concept interacts with ‘things’ as conceptual representations (a distinction that might remind you of Kantian phenomena) rather than as things in themselves (something like the Kantian noumena). For example, the way I internally experience interactions with my spouse is a matter of my self-concept interacting with the concepts and mental representations I have about her. Therefore, our lives are a matter of concepts interacting with other concepts (other people, ideas, and things). Language is the substance of these concepts, as well as the means by which they interact. For this reason, it can’t be overstated how important it is for us to fully understand what concepts are all about, how we form them, how we think using them, how we reify them, and how they lead us astray.

At a fundamental level, we need concepts to think about things because we can only think about concepts not the actual things in themselves (again, recall Kant’s noumena, which we never have direct experience of). Concepts help us think by chunking the world (which is to say, our experiences) into crude discrete categories that are easier to digest, process, and manipulate cognitively. For example, ‘skin colour’ or masculinity/femininity – both of which represent inconceivable variation yet are reduced to crude binary categories like ‘black/white’ and ‘male/female’. Therefore, our concepts do a massive amount of thinking work for us, and so they better be well suited to the task. If they’re too crude, we’ll keep missing the point, and skipping the target we’re trying to think and talk about due to our blunt and crudely-designed tools. For example, as I explain below, we couldn’t understand time and space properly until Einstein revolutionised these concepts in 1905 because all we can think about something is what our concepts allow us or tell us.

Colours like green and blue are concepts, and therefore, represent discrete categories – yet in reality, there’s no clear demarcating point at which blue stops being blue and the light becomes green and vice versa. We experience these as distinct colour categories only because we think according to a language that carves these colours up into discrete chunks for us to think about. This illustrates how our concepts are crudely overlaid on to reality and influence our own thinking and perceiving. I’m sure when you first look at the colour wheel (Figure 6.2), you most likely see clearly discrete colours. In this way, we can appreciate how our concepts mediate and filter – as well as distort – our experience. They’re translators that convert our experiences into the language of our concepts.

So where do our concepts come from? From our own imaginations and those of other people we’ve learned them from. Concepts are imaginary constructions we desperately hope and believe are capable of mapping on to something useful in the world. Like tools – such as a welding machine – we don’t go out into the world and simply find them and pick them up to use. We force them on to our experience like a carefully crafted key made to go into a lock. They’re all we have, and we can’t do any thinking without them (they’re all we can think about). Yet, our concepts are our mere best attempts at abstraction. They act as tools for us, but at the same time, are also as straightjackets to our thinking. When our keys (concepts) don’t fit the locks (usefully represent and map on to real things), we have a tendency to keep trying in vain, or blame the lock, or even break and reshape the lock in order to salvage our beloved concepts. This is true of the concepts in this text such as inference, validity, fallacy, morality, creativity, etc. Consider the utility of a pair of handcuffs, and yet, like concepts, when we’re not willing to let go of them when they stop being useful, they become as helpful as if we were wearing them ourselves.

Let’s lay out some fundamentals more explicitly. Concepts are abstract ideas or principles that are the fundamental building blocks of our thinking and understanding of the world. Concepts are human-made constructions that we develop and use as tools to think and communicate. Concepts are internal cognitive things rather than things that exist outside of us to be discovered – though we believe they capture something important about the world (when I refer to the world like this, I mean both the external world, as well as our psychological world). Once a concept has been named or created, it can be used to describe, explain, and capture reality to improve our knowledge and understanding. In basic terms, because they’re fundamental abstractions, concepts are ideas or words that don’t correspond directly to a specific thing (such as a pronoun might). Concepts can be relatively simple, like ‘joy’ or ‘money’, to very complex, like ‘purpose’ or ‘meaningfulness’. This text has introduced you to a host of new concepts that are nothing more than intellectual devices that will allow you to think smarter.

Concepts are categorisations, and categorisations are concepts. Names or terms for things to represent concepts are ways of representing categories. Anytime you name something as ‘X’, if it’s a new label, you’re creating a category. If you’re using an existing label to denote X, you’re sorting it into the existing category. This idea of terms as categories or groups of things will become central in Chapter 6 when we delve into categorical syllogisms. We’re so obsessed with our concepts as categories that we even make them up and enforce them even when they don’t fit or make sense. Take the popular designation in cooking of ‘proteins’ to refer to a group of ingredients that includes most meats and tofu. If you’re watching a cooking show and the presenter wants to sound smart, they’ll talk about the ‘protein’ in the dish to represent one of these things. Yet using this categorisation (concept) to include tofu (with 8 grams of protein per 100 grams), but not edamame (though it has 11 grams of protein per 100 grams), shows how a term and concept can be inexact, yet still be useful and popularly used (or should I say popularly misused). This is an illustration of how we tend to impose our categories or concepts on to the world as much as we derive them from the world.

We often identify the idea of a concept with the term used to refer to it. The name we use to refer to a concept is its ‘term’, and this can get tricky when concepts change meaning, but carry the same terms (consider Newtonian versus Einsteinian conceptions of space, which we will discuss again soon). A principal concept from our text is thinking itself. The word ‘thinking’ is the term used to point to the very complex concept of ‘thinking’, which might take you a whole lifetime to properly grasp. You can see that concepts are general categories that apply to (and allow us to) think and talk about multiple things at a time. For example, the concept ‘thinking’ doesn’t pick out a specific thought, but refers to a family of activities that share properties and that we can analyse and discuss as a group.

Over time, concepts come and go and should be thought of just like disposable razors. That is, when they outlive their usefulness, they can start to cause problems. We get into trouble by holding on to concepts that are no longer applicable. This happened in physics at the start of the last century, when experimental results weren’t consistent with the long-established, unquestioned concepts of time and space that dated back to Isaac Newton in 1687. Specifically, according to classical or Newtonian physics, the concept of space was a ‘featureless container’ that exerts no effect on its contents. But holding on to this concept of space made experimental results of light bending around heavy objects impossible to understand, until Einstein threw away the old concepts and redefined space as having an active influence on matter and energy (light bends around heavy objects because space itself bends, and this bending influences the trajectory of objects like light photons). The lesson from this episode is to never forget that concepts are imaginary impositions we place on experience. Once we start taking them for granted, they get in the way.

Most revolutions in the history of science are a matter of abandoning old concepts that have exceeded their usefulness and replacing them with shiny new ones, and by doing so, introducing a new language for people to use when thinking about the phenomena under study. As I described in Chapter 3, scientific revolutions are like a change of language. Scientific progress is impeded when we become too attached to long-held and beloved concepts. When scientific concepts are assumed and not repeatedly tested, science gets bogged down and stagnates.

Scientific Concepts

Since we’ve already started talking about the use of concepts in science, and most of you will be studying and planning to enter a scientific field – that of psychology – I’m going to spend some more time on scientific concepts.

All of human thinking operates using concepts, and science is no different. Science itself is a concept and wouldn’t be able to proceed or achieve anything without a heavy reliance on concepts. Despite obliviously priding themselves on being entirely ‘empirical’ and concerned only with observable facts, scientists rely on a huge array of abstract philosophical (i.e. non-observable) concepts. Just think how far science would have progressed in its short 400-year history without using concepts such as ‘cause and effect’, ‘structure and function’, ‘variables versus constants’, ‘theory and reality’, ‘universals versus particular’ – the list is almost endless. It isn’t an accident that I’ve presented a series of concept pairs, because one of the most powerful uses of concepts is to demarcate ‘things’ into opposing categories. One of the most useful aspects of concepts is how they tell us more about something by aligning it with other similar things believed to be in the same category. For example, if I tell you that ‘x’ is a variable, you immediately know a lot about it since you understand what variables are and probably are familiar with a range of different types of variables. Therefore, by me identifying that ‘x’ belongs to the conceptual category ‘variable’, you understand it better even though I haven’t described it in any other way except to give the category title.

The creation of concepts, scientific or not, is an important part of how we understand the world, and these concepts serve as the repositories of our theoretical knowledge. A conceptualisation (building concepts) is a purely creative act. We build concepts up out of primary experiences and the ideas we have about our experiences. Once created, they become ways of thinking in themselves, and in turn, begin to shape our primary experiences. Someone who has never thought of or heard of a concept like ‘cause’ would have a hard time understanding what is happening when they watch billiard balls collide and push each other in different directions. Therefore, concepts as pictures (or models) of something that exists in reality can sometimes lurk unexamined as assumptions in our thinking. We need to be vigilant in examining them and weeding them out when they’re no longer applicable. Sometimes the unexamined assumptions in an argument have to do with the meaning of a concept – that is, an unexamined, possibly faulty definition (like space in Newtonian physics).

Psychological Concepts (aka Constructs)

In psychology, we sometimes use the word ‘construct’ as a synonym for concepts. The term ‘construct’ betrays their man-made nature. Psychological constructs represent and organise complex ideas about mental processes and behaviour that are used to help explain, predict, and modify these ideas. Most of the psychological terms you’ll be familiar with are constructions (i.e. abstractions) that contain important theoretical understandings. For example, think about constructs such as self-esteem, anxiety, wellbeing, coping, or memory. These theoretical constructs don’t directly correspond to any specific thing in reality, but rather complex processes believed to be related in some way. It’s only after we’ve created and learned to think using psychological constructs that we can begin to experience (see) and think about them in our day-to-day lives. And that means we can then begin to do scientific and applied work with these constructs.

Sometimes we even see things in our worlds that aren’t really there because of our reliance and commitment to concepts. Sometimes we take our concepts and constructs for reality and ‘believe in’ these theoretical ideas as though they have an external, objective reality. In this way, we become hypnotised into seeing reality according to our concepts and constructs. This influences us so much, we have trouble seeing when a specific concept or construct doesn’t actually exist. This is a type of reification, which is the process of attributing a concrete characteristic (like existence) to something that’s merely theoretical and abstract. For example, the construct of ‘ego depletion’ has recently been falsified fairly decisively. This begs the question: When all the researchers were seeing ego depletion in their research for the past 20 years, what were they really seeing? This situation shows how our constructs can lead us astray, but also our dependency on constructs in that we can’t really do without them. The phenomena that were experienced in a certain way due to reliance on constructs (e.g. ego depletion) still needs a conceptual explanation, and so scientists now need to go back to the drawing board and reimagine new constructs that can explain the phenomena.

‘Reification’: Reification is when we treat immaterial things (like concepts) as though they’re real and material things. In sciences such as psychology, this is a matter of taking our abstractions – formulations or constructs like mental health diagnoses – as though they were real independently existing things out there in the world, rather than conventions and constructions of our own imagining. Treating some ideas (like our notions of space and time) as though they’re real things out in the world is a risk that blinds us into not seeing things for what they are – we can’t get our concepts out of the way to see real things as they might really be.

We can’t think of psychological ideas like mental illness in any other way than with the concepts we have available such as depression, anxiety, distress, psychosis, personality malfunction, etc. Our thinking about these phenomena is made immensely more powerful by these concepts, but is also tied to and bound by them. Always view your concepts (like the ones in this text) with scepticism and a willingness to ditch them like a disposable razor that has done its job. We imagine them, and hope they fit, because without them, we experience great discomfort – in the same way a strange emotion we can’t label disturbs us immensely.

Language as a Rhetorical Tool

Given the power of language and concepts to influence our thinking, experiences, and beliefs, it’s no surprise that we routinely use language as a rhetorical device to persuade others. People hijack our concepts to make us think and behave according to their priorities. Our suite of concepts – and our commitment to them – represents one of the weakest points in our critical thinking armour.

As I said in Chapter 2, words are always rhetorical weapons, and sometimes this weapon isn’t used honestly, genuinely, or with good intentions. Dishonest actors have a range of rhetorical devices at their disposal to increase the persuasiveness of their speech. Though I paint a fairly dire picture here, the use of these tactics isn’t always underhanded –sometimes they can be used to communicate more information than what is literally meant by a phrase. From a critical thinking perspective, if you’re not on the lookout for them, you might fall prey to them.

There are dozens of crafty rhetorical devices, and the additional resources at the end of this chapter will introduce you to a number of them. I only want to give you a taste in this chapter, so here we’ll focus on two: the use of emotive and colloquial language.

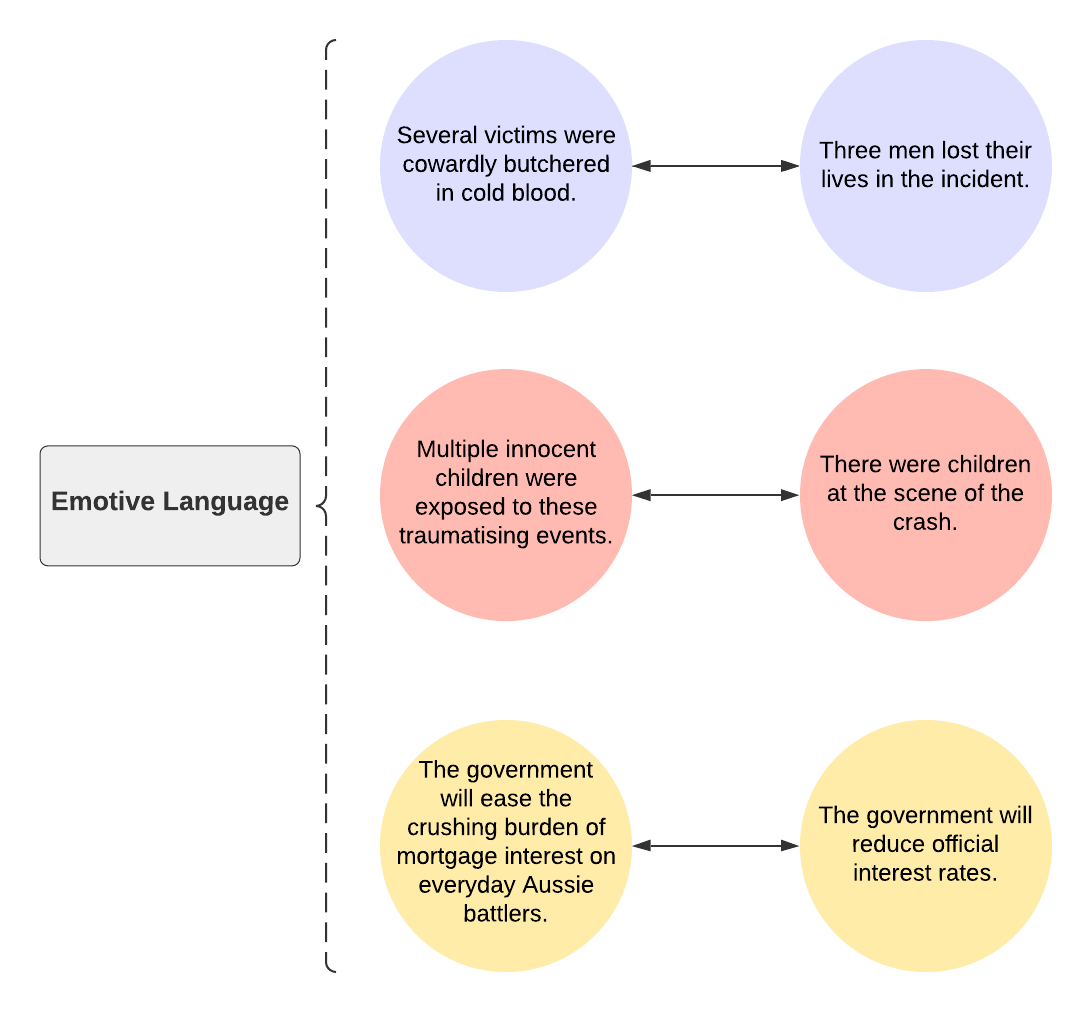

Emotive Language

Emotive language is the deliberate use of specific words solely to evoke emotions in the audience and make the proposition appear more plausible. Someone uses emotive language with the intention of manipulating the affective state of the audience. This is often confused with emotion language. An emotion term can be used emotively if it’s used with the intention to create an emotional experience in the person who is the audience. However, emotive language often doesn’t reference an emotion at all, as this is beside the point. Often, referring to specific emotions isn’t the most effective way to create an emotional experience in an audience.

Let’s look at some examples for each. Notice how the statement might make you feel.

The first example of each statement includes specific terms that are intended to rouse the audience to have emotional experiences. Importantly, notice the second version of each statement may still arouse emotion, but there is no intentional cherry-picking of words solely for this purpose. Emotive language isn’t a matter of whether a proposition or statement may have emotional content or even whether the presenter of the statement is presenting it to evoke emotion –it’s about whether they’re intentionally manipulating language to produce this effect. A statement can involve a topic that elicits emotion, but this isn’t the same as using emotive language.

Some instances of emotive language also employ colloquial language to reinforce the emotive expressions.

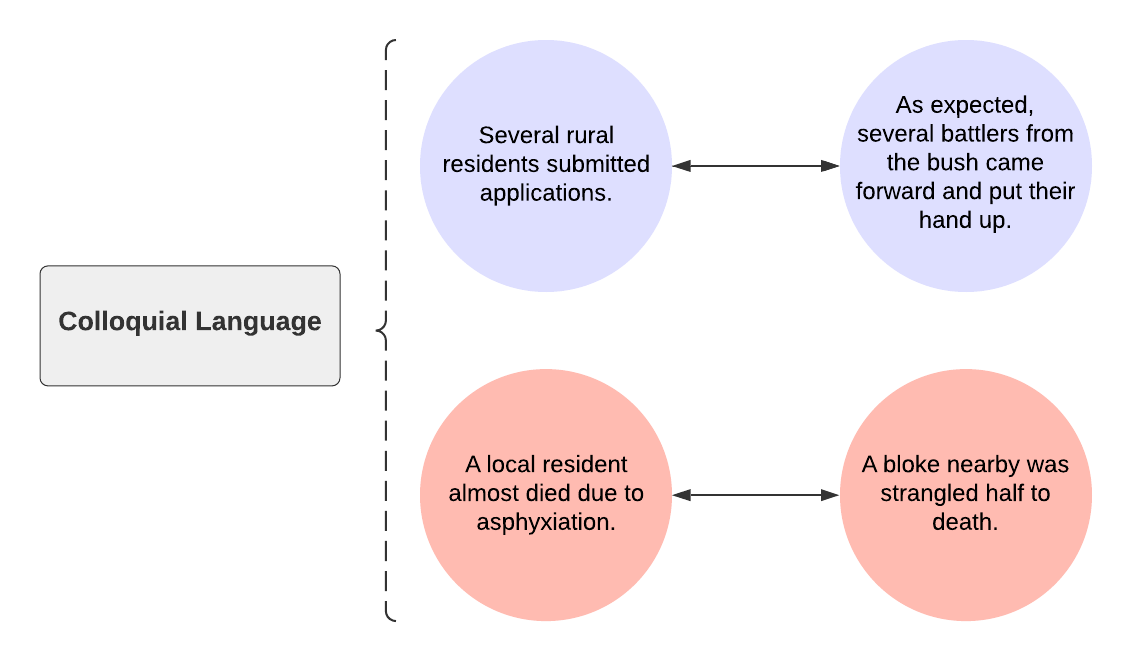

Colloquial Language

Colloquial language is the use of everyday casual language to be more persuasive. Individuals use informal language such as slang and jargon (though slang and jargon aren’t exactly the same as colloquial language, they’re forms of it) because audiences find these phrases comforting and reinforcing, and so they can be powerful persuasive tools. Imagine the difference if an Aussie politician states, ‘We have the situation under control’ versus ‘She’ll be right, mate’. Now, you might not personally find the latter any more persuasive, but many people often find comforting colloquial expressions more persuasive. This example also illustrates that many colloquial expressions are specific to a geographical area. However, this strategy can be used more broadly and rely on more casual modes of language in order to bring your audience on side or make them more relaxed and friendly to your point.

Let’s look at some more examples. Similarly to the emotive language examples above, notice how each statement might make you feel:

As you can tell from these examples, colloquial expressions are often used to evoke emotions in the audience, so sometimes there isn’t a clear line between emotive language and colloquial expressions.

Additionally, the reverse strategy is a powerful rhetorical and commonly used device. That is, many speakers and writers make their expressions unnecessarily complex and technical so as to be more persuasive. This is a cheap tactic that’s easy to spot and has the opposite effect most of the time. It conveys a sense that the author doesn’t fully respect or trust their own ideas enough to use the simplest, most straightforward language to represent them. Students also fall into this trap when writing assignments by thinking the more they use the thesaurus, the more marks they’ll score. This may work sometimes, but mostly it just backfires by obscuring their point. For example, consider the following sentences carefully crafted by a student: ‘The presently assigned paper necessitates an eloquently articulated analysis of the existentialist perspective as it pertains to contemporary living. You should adumbrate the points which represent the sine qua non of your analysis.’ Most lecturers marking this don’t have the time or energy to decipher this mess, and whatever clever point may be buried within it is lost forever, earning the student no marks.

One final note on the use and detection of emotive and colloquial language (and yes, this will seem repetitive because students always struggle with this distinction): a phrase is only colloquial or emotive if it intentionally uses colloquial or emotive words in order to be more convincing. Emotive or colloquial language has nothing to do with content. For example, if you’re careful, you can discuss all kinds of emotion-arousing topics – like infanticide or the Holocaust – and never be guilty of emotive language.

Notice that the content and message of the statements in the examples above are the same in each column. The only difference is that the ones on the right use overtly emotive or colloquial expressions in an attempt to con the audience. Emotive and colloquial language is about the words used, not the topic they’re used to describe.

Additional Resources

By scanning the QR code below or going to this YouTube channel, you can access a playlist of videos on critical thinking. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

By scanning the QR code below or going to this YouTube channel, you can access a playlist of videos on critical thinking. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

Further Reading:

‘The Russian Blues’ in the Scientific American

Caldwell-Harris, C. L. (2019, January 15). Our language affects what we see. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/our-language-affects-what-we-see/

Thoughts affect words and words affect thoughts (article and video)

Thierry, G. (2019, February 27). The power of language: We translate our thoughts into words, but words also affect the way we think. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-power-of-language-we-translate-our-thoughts-into-words-but-words-also-affect-the-way-we-think-111801

- Sapir, E. (1929). The status of linguistics as a science. Language, 5(4), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.2307/409588 ↵

- Whorf, B. L. (1940). Science and linguistics. Technology Review, XLII(6), 3-7. https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/p15999coll16/id/104384 ↵

- Everett, C., & Madora, K. (2011). Quantity recognition among speakers of an anumeric language. Cognitive Science, 36(1), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-6709.2011.01209.x ↵

- Sapir, E. (1929). The status of linguistics as a science. Language, 5(4), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.2307/409588 ↵