Chapter 3. Perceiving and Believing

Learning Objectives

- Understand the relationship between our senses and the signals they transform and transmit

- Understand the bottom-up and top-down pathways by which perception is created

- Appreciate that sensation and perception are creative acts

- Understand the lesson of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

- Identify between Locke’s primary and secondary qualities

- Understand the distinction between Kant’s noumena versus phenomena

- Understand the role of models and how they frame and shape our interaction with the world around us

- Recognise the structure (holistic) and power of our belief systems to shape our experiences

- Understand appropriate attitudes to hold towards our beliefs and mental models.

New concepts to master

- Signal

- Top-down versus bottom-up processes

- Heuristics

- Cognitive biases

- Allegory

- Primary versus Secondary quality

- Phenomena versus noumena

- Naïve realism

- Model

- Confirmation bias

- Holism.

Chapter 3 Orientation

In this chapter, we start to venture down another rabbit hole and look closely at the – often faulty – tools we use for gathering information and forming beliefs, and also the make-up and function of these beliefs. That is to say, the instruments we’ve evolved for picking up perceptions and turning these into beliefs about the world. Everyone knows from popular perceptual illusions and magic tricks that normal everyday perception isn’t exact or very reliable, but few people understand the ways it’s vulnerable to mistakes and biases and how to manage these vulnerabilities. I hope after this chapter, you’ll be in a better place to understand this and improve the way you perceive and believe.

Chapter 2 Review

Chapter 2 gave us many new conceptual tools with which to understand and improve our thinking and evaluate claims made about the world. The last chapter definitely covered a lot of new territory, so if you were feeling a little overwhelmed, don’t worry – we’ll go back over most of it and apply it several times in later chapters.

Chapter 2 was organised into three categories. The first was theory, which focused on developing essential knowledge and conceptual tools like logic, argumentation, fallacies, biases, inferences, language analysis, critical appraisal steps (e.g. knowing what counts as a reason and what counts as evidence and how to evaluate the credibility of these), etc. The purpose of this theoretical information (even if it was a tad dry) was to equip you with necessary conceptual tools that will make you a much more skilful critical thinker. The second focus of the last chapter was application, and we went through some basic steps to practice the ‘how’ of applying the new theoretical concepts. Practice is critical to ensuring we can execute these moves when we need them. Finally, we looked at optimal dispositional traits or attitudes, and how cultivating the best attitudes, perspectives, and approaches to the world around us can maximise our critical thinking abilities. Some good attitudes to cultivate are scepticism, inquisitiveness, open-mindedness and even-handedness, and introspection and insight, though this list is far from complete. As with everything in critical thinking, developing these attitudes takes time and practice.

Many new concepts were introduced last chapter, although many of these are just extravagant new names for ideas you’re probably already familiar with. For example, we began at the simplest level by defining statements within arguments as propositions or declarative statements – which is just fancy talk for a sentence that proposes a fact about the world. These types of sentences have the property of being either ‘true’ or ‘false’, and we determine their ‘truthfulness’ (or ‘false-fulness’) on the basis of reasons and evidence. We primarily focused on two types of propositions: premises and conclusions.

Claims about the world rest on arguments. Anybody making a claim has the burden of presenting an argument that shows why their claim is true (if they can’t or won’t do this, you can dismiss the claim outright). Therefore, arguments are key to critical thinking and were central to our discussion last chapter. We learnt that an argument is simply a collection of statements that relate to each other in a structured and purposeful way. The primary purpose being to try to convince an audience of the truth of a claim or proposition, named the conclusion. Statements offered in support of the conclusion are called premises, and they represent the reasons or evidence that supposedly back up the conclusion. The connective tissue between premises and conclusions is called inference. We learned that to infer is to venture beyond what the premises are claiming to conclude a new fact or piece of knowledge. Therefore, we’re making an inference when we make a new claim on the basis of the true premises that are already known.

With this in mind, we can scrutinise arguments in several ways: analysing the credibility or truthfulness of each premise in its own right, and also analysing the credibility or validity of the inference from the premises to the conclusion. In this way, the truth or falsity of any conclusion rests on two things: firstly, the credibility of the premises (question are they true or not) and secondly the credibility of the inferential move from premises to conclusion (question whether the premises provide any reason for believing the conclusion).

Going beyond the analysis of arguments, we became familiar with some broader tools in our critical thinking toolbox. We were introduced to the analysis of meaning and language, and the necessity of clear and unambiguous definitions of the terms that go together to make up our propositions. We briefly touched on the analysis of scientific methods, which are the best approaches to gathering evidence to support claims. Importantly, we should always keep in mind that not all scientific methods furnish equally credible evidence, and some so-called ‘scientific’ studies produce worthless evidence. Therefore, we should never accept, without critical analysis, any evidence just because it might be ‘scientific’. We introduced the idea of fallacies and biases, what forms these come in, and how to detect them. Finally, we spent time emphasising the importance of clarifying values and judgements and how these are the foundation for beginning – and the reason for continuing – our critical thinking journey.

Okay, that’s enough rehearsal of Chapter 2 – it’s time to get into the meat of Chapter 3.

Senses and Signals and Their Top-Down Influences

In this part of the chapter, we’ll touch on the world of signals and noise that we interact with. We’ll consider what is actually out there to be detected, how we detect it, and what things can go wrong in this process.

‘Signal’: Signal is a bit of a loaded term in that it implies ‘information’. Picking up a radio signal or a cellular phone signal means you’re receiving information. This term is often contrasted with the term ‘noise’, which is used to refer to non-signal or irrelevant signals. Almost anything can be a signal if it ‘signals’ information we’re interested in. In contrast, something that’s random can’t contain useful information, so randomness is always noise (think of whether you can predict a random outcome like a coin toss – the fact that you can’t is because it can’t be correlated with anything, and therefore, random processes carry no meaning or information).

If we’re doing some stargazing and looking to see a particular constellation, we’re looking for a specific signal (which is the light emitted by the stars that interest us) and we need a way to filter out the noise (which is all the other light coming from other sources). In this sense, the distinction between what is signal and what is noise is based on our purposes and desires. Our senses and brains are powerful instruments that detect, filter, and process signals amid noise. A lot of this work happens without our conscious awareness and can be vulnerable to a range of biases, which we’ll discuss in this chapter.

A simple overview of the signal detection apparatus within our body will serve as a useful starting point. Our body has a network of sensory receptors to detect signals. Some of these are on the outside of our bodies – such as our eyes, ears, nose, mouth, etc. – which are like the peripherals (mouse and keyboard) on a computer. Others are internal, such as those that register pain (kind of like the internal heat sensor inside a computer). Our external receptors are responsible for detecting some form of incoming energy, which is then converted to electrical signals that can be transmitted and interpreted by the brain. At this point, we can say that ‘sensation’ has taken place, but an experience or a ‘perception’ has not. The raw sensations are rarely of great use to us until they’re worked on by the brain. There are some exceptions to this, however. For example, the ‘fight or flight’ response is a rapid operating system that’s triggered by threat detection and produces an immediate and automatic physical response that prepares the body to fight or run. Rapid automatic responses like these can be triggered by sensations without requiring the conscious perception of fear, which often happens only after we recognise our bodily reaction.

This commonsense picture of ‘bottom-up’ sensation and perception is very common, and while it’s correct, it’s partial and a little too simplistic. It assumes there are a manageable number of unambiguous signals contacting these sense registers, and also that the brain is more of a passive receiver of these signals. Both of these assumptions are false. We live in an environment flooded with potential signals, and with a good dose of nuisance noise thrown in. The famous pioneering psychologist of the nineteenth century, William James, described the world of the newborn as a ‘blooming buzzing confusion’; however, this is actually an apt description for the torrent of signals that flood our senses at every age. The point James was making is that to have anything like sensible and useful perceptions, a newborn requires cognitive faculties that drive the senses in a top-down manner. A grown adult would experience the same overwhelming and incomprehensible ‘blooming buzzing confusion’ if they lost all the top-down influences shaping their experiences.

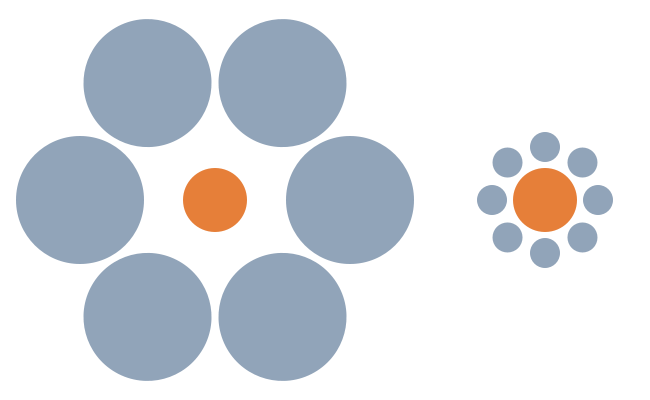

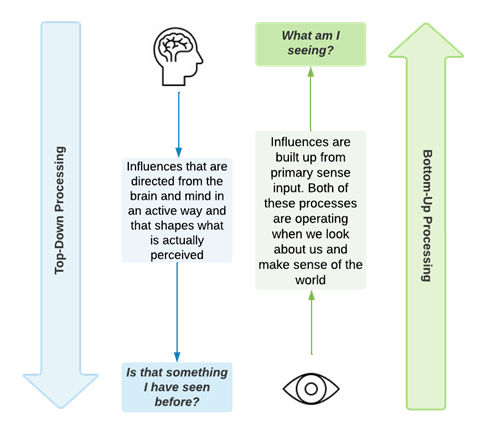

‘Top-down’ versus ‘Bottom-up’: In cognitive psychology and perception theories, a distinction is made between top-down and bottom-up processes. Top-down processing involves influences that are directed from the brain and mind in an active way and that shapes what is actually perceived. Bottom-up processes refer to the way perceptual influences are built up from primary sense input. Both of these processes are operating when we look about us and make sense of the world. Perceptual illusions are possible because they take advantage of top-down processes overriding bottom-up sensations and producing perceptions that are not ‘really there’. For example, in Figure 3.1 (known as ‘Ebbinghaus’ Titchener Circles’), influences from our top-down processing, which rely heavily on context, make it difficult to realise that the orange circles are the exact same size.

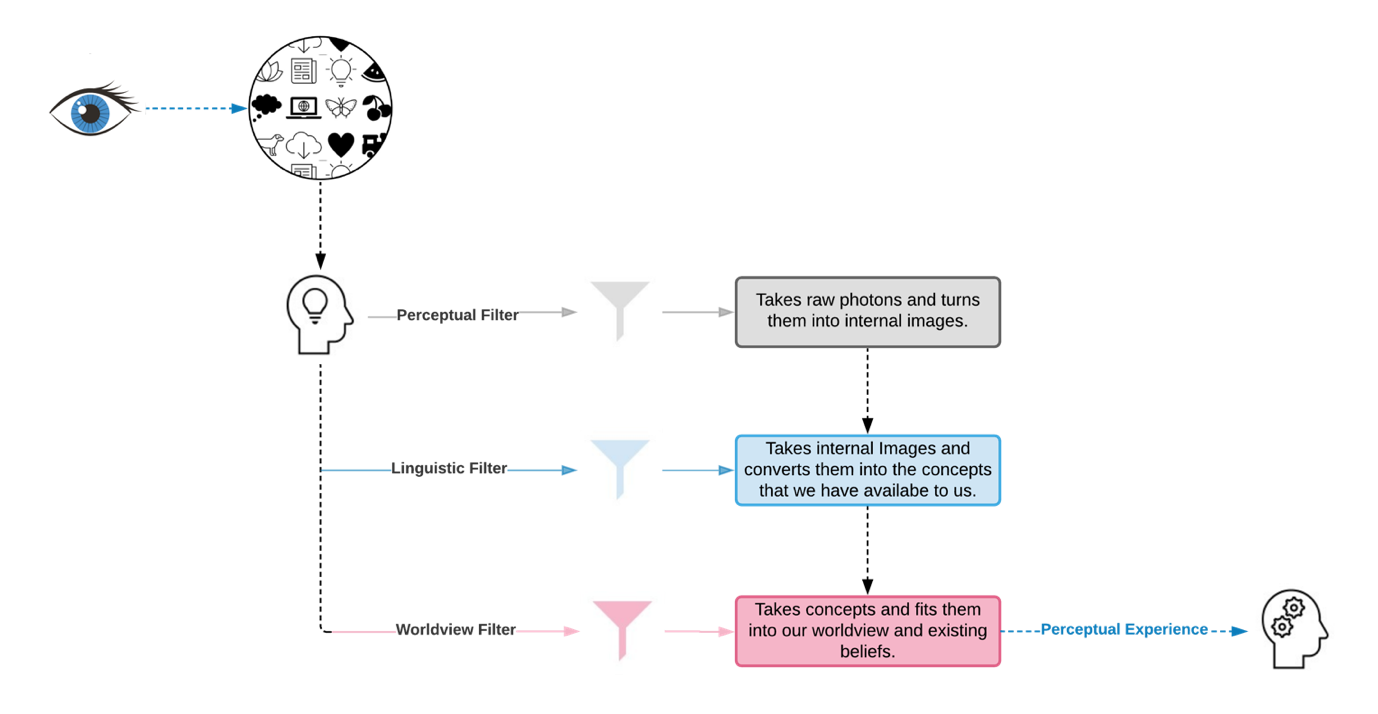

The distinction between top-down and bottom-up processes is a useful conceptual tool with which to better understand perceiving and believing. Both processes are essential, as our actual perceptions are a combination of bottom-up and top-down activity (see Figure 3.2).

So, the first task of our sense perception architecture is to direct and discriminate. This top-down influence on our sensation shouldn’t be seen as a liability, but is actually very necessary. Useful perception could barely happen without it (recall James’s ‘blooming buzzing confusion’). For example, the sheer number of photons hitting our retina at any point in time is entirely overwhelming and impossible to process into a useful image of anything – our brain needs to be in the driver’s seat behind our senses so they can focus on some signals at the expense of others. Another example of the usefulness of top-down direction is the ‘cocktail party effect’. I don’t usually get invited to these types of things, but I’ve heard stories that they get a little rowdy. It’s actually a miracle of perception that anyone can filter out a thousand voices to clearly hear the person speaking to them. With all this in mind, perception is better thought of as a creative act that involves our brain and mind filtering – though it’s more like transforming – raw sense information into perceptions that may, or may not, be accurate representations of the world. It’s always useful to keep in mind that these systems haven’t evolved to produce ‘accurate’ representations of the world, but rather are only devoted to producing the types of pictures that increase our chances of survival. ‘Accuracy’ doesn’t always equate to ‘survival value’, and therefore, it’s lower on the priority list for our brains.

An example of where this top-down driving of our sense input can go awry is in certain mental illnesses. Many mental illnesses alter our perception of the world around us. This is, of course, most pronounced with psychotic disorders that include delusions and auditory or visual hallucinations, but is also more subtly present in other conditions. For example, individuals with anxiety disorders experience heightened sensitivity and selective attention to potentially threatening signals[1]. Furthermore, individuals with these disorders show a lower ability to actually discriminate between neutral and threatening stimuli[2]. In this way, processes originating from the mind and brain directly shape primary sensations.

These top-down influences are not reserved to cases of mental illness. There are a host of other processing influences that shape what and how we actually see and perceive the world. One group of influences has to do with improving our processing capacity and speed. These are called heuristics and are types of mental shortcuts in our perception and cognitive processing of information.

‘Heuristics’: These are strategies that act as shortcuts in how we process information and make decisions. They’re tools we use to simplify complex tasks. They can be thought of as rules of thumb that are necessary to speed up perception and reduce the effort or resources required to process information and make decisions. The drawback of heuristics is that they’re error-prone because they’re employed to produce ‘good enough’ outputs, not necessarily ‘optimal’ or correct outputs. Therefore, heuristics are powerful space and time-saving tools, but the trade-off is that they’re much more prone to biases and errors. The ‘fight or flight’ response I discussed above is an example of a heuristic intended to improve our survival. This heuristic drives a rapidly triggered physiological system that’s engaged at the slightest sight of threat in our environment. This system might save our life one day, even though most times it just leaves us embarrassed at our overreaction to a coiled hose we caught out of the corner of our eye (my brain screamed ‘snake’). Another everyday instance of our reliance on heuristics is when we might pay closer attention to our valuables when lined up in front of a person with dreadlocks, shabby clothes, and face tattoos at the grocery store (using stereotypes is just one instance of heuristics). Thinking less heuristically about this person might lead us to consider that their outward features have nothing at all to do with possible criminality.

The verywellmind website provides further information about and examples of heuristics.

If you’re unconvinced of your continuous reliance on heuristics, think about the following problems (most people get them wrong because of heuristic thinking). The questions are not hard and as soon as you know the answer, you’ll probably slap yourself in the head, but you’re likely to get them wrong because of your reliance on heuristics.

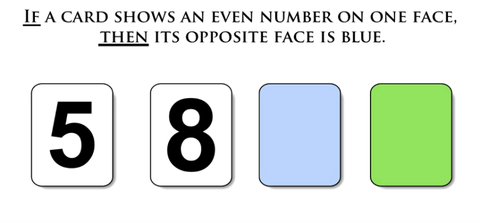

One last one. This next logic puzzle was devised by Peter Cathcart Wason in 1966. In this puzzle, we’re given four cards with numbers on one face and colours on the opposing face:

- The numbers are either odd or even numbers, and the colours are either blue or green.

- There’s a claim about the cards that says, ‘If a card shows an even number on one face, then its opposite face is blue’.

The task is to decide which two cards have to be flipped over that allows you to properly tests this claim or hypothesis. [3]

Once you learn about the types of deductive arguments called modus ponens and modus tollens, this type of puzzle will be straightforward for you to solve. A tip for now is that if you got it wrong, you were probably focusing on confirming the statement rather than trying to falsify it.

We wouldn’t want to eliminate heuristics from our lives, as this would leave us paralysed from the sheer amount of cognitive processing and decision-making that burdens us each day. But if we’re going to live with heuristics, we need to be aware of them and how they influence us. Another way to think of heuristics is that they ‘bias’ us to viewing and understanding things a certain way. The word bias is likely to seem quite negative, but it’s more like a tendency to interpret things a certain way, which can be positive or negative. Biases have evolved to have important benefits for us (i.e. overreacting to coils of hose has immense survival value). Harmful biases are those filters or heuristics that skew and distort our thinking, leading us away from the truth. (This is typically what people mean when they refer to bias.)

Stereotypes are an example of a heuristic that allows us to make a rapid – though often biased – decision about someone, and have helped improve our survival value. In critical thinking terms, we’re mostly concerned with heuristics that we call cognitive biases. You’ll see from the definition below that heuristics and cognitive biases can often be used interchangeably.

‘Cognitive biases’: Like fallacies (which we encountered in our last chapter), cognitive biases are a big concept in the context of our critical thinking training. Cognitive biases are systematic shortcuts in thinking that we all use – whether we’re aware of it or not. ‘Bias’ is usually a nasty four-letter word when talking about thinking, but as I pointed out, biases can be quite adaptive in helping us quickly grasp things and make decisions (they evolved for good reasons!). Biases are like shortcuts in thinking that can be useful at times, but because they’re designed to be fast and rough processes, they’ll more likely than not produce simplistic, uncritical, and faulty thinking. I like the way Jeff Jason describes bias in this context: where our brains make decisions with incomplete information deriving from our existing beliefs.[4] He calls biases ‘decision accelerators’.

There are many cognitive biases that we use without realising it – later in the chapter, we’ll learn about a common cognitive bias called confirmation bias. You can find lists published online that compile the most important or most commonly used cognitive biases (e.g. on Wikipedia). Studying these can be a very useful way to start detecting when you’re relying too much on them. Given the nature of our critical thinking focus, you can anticipate we will have a lot more to say about cognitive biases. This chart of fifty cognitive biases in the modern world is a good study guide.

Signal Detection & Transformation: Approximating Imperfect Perceptual Machinery

As I mentioned above, we have many sense organs that are sensitive to input from inside and outside our bodies, including the five basic senses everyone is quite familiar with: sight (vision), hearing (audition), smell (olfaction), taste (gustation), and touch (somatosensation). However, we actually have many more senses – some scientists believe the number could be as high as 20. Some of these other senses we’re very familiar with and simply take for granted. For example, proprioception allows us to ‘know’ where our body parts are in space without seeing them (close your eyes and touch your nose to test if yours is working). Equilibrioception (our sense of balance) and thermoception (our sense of temperature) are others we use every day, but might take for granted. Chronoception (sense of passing time) and kinaesthesia (sense of movement) are others.

But, I hear you asking: ‘What’s this got to do with critical thinking?’. well, the point is these are rather crude machinery that are sensitive to registering a certain type of input, and they all get it very wrong at times. Knowing the limitations and vulnerabilities of these systems is a good way to start developing the right attitudes (particularly humility) about our beliefs. The second thing you’ll need to develop is vigilance to accommodate these vulnerabilities and how they influence your formation and revision of beliefs. The impressions registered by these senses serve as the raw data that, with a lot of creative input from our brains, go onto make up our picture of the world. Yet, we know scientifically that the world our senses propose to us is neither complete nor especially accurate. Our senses are flooded with billions of signals that require a brain to filter and resolve them into useful information. We can’t function without filtering input received by our senses – without these filters, we’d be useless and know nothing. It’s a little like wrestling with those old frustrating Magic Eye pictures (called ‘stereogram’ or ‘autostereograms’) until an image of something obvious emerges.[5][1]

Apparently, there’s a Buddha statuette buried inside Figure 3.4. I know it’s there because I put it in the image myself. But I still can’t see it – I was never very good at these and would just pretend that I could see the hidden image, so people would stop asking me (don’t worry if you can’t see it – apparently they work better on paper than on screen).

Almost all our senses function to turn some type of physical contact (like air vibrations hitting our ear drum or vibrating photons hitting the retina inside our eye) with the outside world into an electrical signal that our brains can process and interpret (our brain operates almost exclusively on electrical signals). Interestingly, these signals are not much like what we end up experiencing. Our perceptions are transformed versions of the raw sense data that give us a much richer experience of the world. For example, light is nothing more than electromagnetic radiation that’s made up of vibrating energy packets called photons. These packets vibrate at different wavelengths, which the retinas in our eyes react to and gives us the experience of sight and colour. Our experience of sound is nothing more than our brain’s interpretation of vibrations of air that our eardrum is capable of reacting to. These vibrations are also of different wave lengths, and the different wave lengths produce the differences in sound pitch that we perceive. This is why it’s completely silent in space – because there’s no air, and sound is nothing more than our brain’s interpretation of vibrating air. Consequently, this means the world outside our sense equipment and the creative input from our brains is actually completely silent and colourless. A large part of our experience of things like colour and sound is a result of top-down processes. It turns out the most realistic movies are those old silent black and white ones. This is an important insight to consider as it sheds light on (no pun intended) how creative our own brain is in producing our experience of a colourful world filled with sounds. We’ll pick up this thread below when we discuss objects’ primary and secondary qualities.

Our minds carefully influence the sensations and perceptions we have, in the same way a museum curator painstakingly organises and presents exhibits to tell a rich story. This fact can easily be observed (again, no pun intended) when we notice how various psychological states influence our perceptions. We touched on this earlier when we discussed the case of mental illness shaping our sensations and perceptions, but this is just a readily observable instance of a normal, everyday occurrence. Top-down influences infect all perceptions, regardless of your mental health. For example, when we’re highly stressed, our sensation and perception systems shift gear and become more focused on specific signals. One recent experiment showed that ‘stress impairs the visual discrimination of scenes’.[6] This fact has produced some funny videos on social media involving interesting pranks.

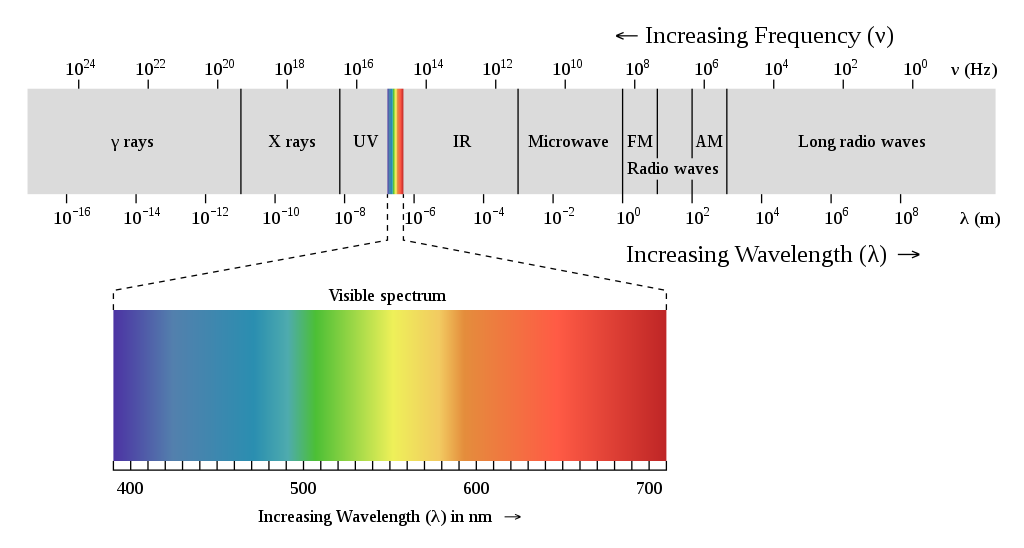

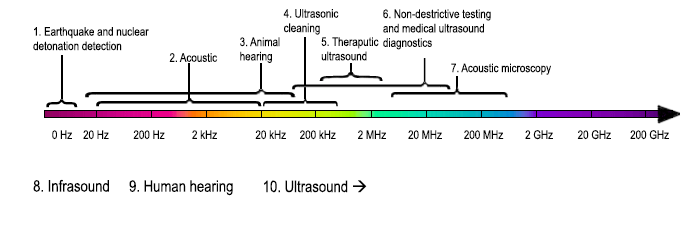

In addition to our perceptual experiences being a result of the creative top-down activity of our minds, our sense organs are actually only sensitive to a small proportion of the possible range of signals in the first place. For example, see Figure 3.5, which illustrates the tiny proportion of the spectrum of electromagnetic radiation that our eyes can detect (we can perceive less than a ten trillionth of all light waves). Our auditory sense machinery only registers a similarly small proportion of the possible range of sounds (Figure 3.6 shows the acoustic range that humans can actually hear – between 20hz and 20khz). Air vibrates at a wide range of possible frequencies, yet our ears and brains only respond to a small proportion of this spectrum. Therefore, the world around us is flooded with information and signals that we’re ordinarily unaware of. Thankfully, we’ve developed powerful instruments to aid our senses in being more sensitive to more of this information. But these instruments embody new problems with perception and sensation that we won’t go into here.

Broadly speaking, this description presents some of the things a critical thinker should be aware of when it comes to understanding the basic processes of sensation and perception. Another fact that should be remembered is that these processes don’t even work in the same way for different people. Different people have difference experiences of the exact same thing. This became famously apparent in 2015 with the viral social media sensation #TheDress. The episode of ‘the dress’ revealed important differences in people’s colour perception. Some viewers see this dress as blue and black, while others see it as white and gold, and scientists aren’t entirely sure why. Some hypothesise that our eyes become accustomed to certain types of light colours depending on our lifestyles. For example, people who are night owls see a blue and black dress, while people who are early birds see a white and gold dress based on the type of light they’re used to seeing.

It turns out there are more individual differences in how our perceptual systems work than we might have previously realised. It can be a little disconcerting to realise that two individuals with properly functioning visual systems can look at the same stimuli and see different things.

In light of all this, the old saying ‘Seeing is believing’ starts to look very uncertain. This means we should be modest about what we perceive of the world and the role – and reliability – of our sense organs in forming and shaping beliefs. Understanding the vulnerabilities and limitations of our signal detection systems is the first step to being a more critical consumer of sensations and perceptions. Being aware that we never see the whole picture – and often don’t even see a very accurate version – is a good remedy for overconfidence in our senses. Also, being aware of differences in how our sense machinery and perception processes operate helps us understand others’ better, and allows us to be more understanding of varying beliefs and worldviews. This understanding can help better equip us to deal with contrasting beliefs and perceptions. These issues also underscore how important it is to develop those attitudes we talked about in the last chapter. Specifically, scepticism and open-mindedness regarding sense perception.

Philosophical Perspectives on Sense and Perception

This section is a little theoretical, but don’t worry – we don’t dive too deep. It’s useful to give some background context to these discussions and reference some of the great thinkers throughout history who grappled with these very same issues. Understanding some of the broader intellectual debates that concern the problems we’re learning about is also useful for deepening and contextualising your learning about critical thinking. As I mentioned already, this is really about you learning new conceptual tools, new terms, and new ways of looking at everyday problems. Seeing these issues from as many different angles as possible will increase your ability to understand them and improve your thinking. These are inspiring thinkers that are well worth checking out further.

Allegory of the Cave (Plato)

In Chapter 1, we met an inspirational thinker named Socrates (469–399 BCE). Almost everything we know about Socrates is due to his student, Plato (427–347 BCE), who wrote down the debates and discussions held by Socrates. Like Socrates, Plato was one of the most brilliant thinkers of all time, and one of his most famous teachings is a classical thought experiment to probe our intuitions about sensation and perception. This teaching is from his book The Republic (Book VII), which reports on a dialogue Socrates had with various Athenians and foreigners about the nature of justice.

‘Allegory’: An allegory is a story or poem in which the events or characters are used to communicate important – sometimes hidden – messages. This hidden meaning usually concerns some deep topic relating to morality, politics, or philosophy. The allegory is a literary (or storytelling) device intended to reveal something important about human existence.

Using this allegory, Plato is attempting to distinguish between people who mistake sensory knowledge for the truth and people who really do see the truth.

The allegory goes like this:

Envision human figures living in an underground cave with a long entrance across the whole width of the cave. Here they have been from their childhood and have their legs and necks chained so that they cannot move and can only see before them, being prevented by the chains from turning their heads around. Above and behind them, a fire is blazing at a distance. They see only their own shadows, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave. For how could they see anything but the shadows if they were never allowed to move their heads? Between the fire and the prisoners, there is a raised way and a low wall built along the way like the screen which puppet players have in front of them over which they show the puppets. You see men passing along the wall carrying all sorts of articles, which they hold projected above the wall: statutes of men and animals made of wood and stone and various materials. Of the objects which are being carried in like manner, they would only see the shadows. And if they were able to converse with one another, would they not suppose that they were naming what was actually before them? And suppose further that there was an echo which came from the wall. Would they not be sure to think, when one of the passers-by spoke, that the voice came from the passing shadows? To them, the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.[7]

The shadows in Plato’s cave allegory (Figure 3.7) are the prisoners’ only perceptions of reality, but they’re not complete or accurate representations of the outside world. Plato claimed there were three higher levels of knowledge: the natural sciences; mathematics, geometry, and deductive logic; and the theory of forms. But for our purposes, it’s a powerful story that nicely captures some of the concerns about our perception that we discussed earlier. Our sensations and perceptions are mediated – they’re not raw or pure input from the outside world, but are filtered, transformed, and indirect. Mediated here just means that they pass through processing (like being turned into shadows cast by a fire) before we experience them, and that our contact isn’t direct.

Primary and Secondary Qualities (Locke)

We’ve discussed how some of our perceptions come directly from the objects we sense (such as the feel of a solid surface), while other perceptual experiences (such as sound and colour) are products of how our mind and brain transform and interpret raw sensations (of shaking air and light wavelength) into perceptual experiences. This distinction has been most famously articulated by English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704),[8] in his famous book, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689).[9]

Primary qualities are inherently part of the objects being sensed, while secondary qualities are add-ons created by our senses and mind. For example, there’s nothing in the outside world like ‘sound’, only vibrating air. This vibration is a primary quality of air, while our experience of sound is a secondary quality produced by our senses and our mind. Primary qualities are aspects of things that are there regardless of us and our senses or our creatively interpreting minds. Secondary qualities require our senses creatively interpreting minds to exist. Secondary qualities are interpretations and experiences that we add to the primary qualities, which are the attributes things have in themselves. Foods don’t have tastes on their own, but rather they simply have primary chemical properties that our tongues and our minds interpret and transform to produce our own wonderfully complex subjective experience of taste, which is the secondary quality.

Locke argued that all that’s actually ‘out there’ (outside our heads) are colourless, tasteless, soundless, odourless corpuscles (atoms or chunks) of matter. Our experience of this matter is far richer and more interesting, however, due to secondary qualities. We perceive a world rich in colour, taste, smell, sound, and warmth or cold. These are secondary qualities because they don’t necessarily resemble anything ‘out there’ in the world, but rather are experiences given to us by our own mind as a result of ‘things’ out in the world. According to this view, sense objects often contain properties or cause experiences that have more to do with how our mind interprets and interacts with the objects, rather than with the objects themselves. The primary qualities are inseparable from matter, whereas the secondary qualities are not really qualities of matter, but are more like ‘powers’. These objects have to produce certain experiences in us. It’s useful to consider this distinction in our experience or knowledge of objects, and to think about what perceptual experiences arise from the objects themselves, versus those that are creative products from the interaction of our own mind and brain with them.

‘Primary versus secondary quality’: One useful way to distinguish between these types of qualities is to think of primary qualities as those qualities that sense objects have independently of our perception of them. Secondary qualities are a category of perceptual experiences that outside objects produce in us that are dependent on the working of our own minds and brains. In a way, secondary qualities can be derived from primary qualities, but require some creative input of our own perceptual systems.

Noumena Versus Phenomena (Kant)

Another distinction that sheds light on our perception and sense experiences is between phenomena and noumena. The most famous account of this comes from modern German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), who is another of the most brilliant and influential thinkers of all time.

Another distinction that sheds light on our perception and sense experiences is that between phenomena and noumena. The most famous account of this is due to Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) who was a modern German philosopher and considered one of the most brilliant and influential thinkers of all time.

Earlier in our discussion of sense and perception, we discussed the things outside us that give rise to sense experiences. This is what Kant is referring to when he talks of noumena (plural of noumenon). This is contrasted with what he called phenomena, which are our very experiences of things. Phenomena are the way things display themselves to us or, to our senses. Kant believed this distinction to be crucial to our understanding of the world and the activity of our mind in producing sense experiences. Therefore, noumena are ‘things in themselves’ and are ‘really real’ in a way, but unfortunately, are things we never have direct contact with. Phenomena are our experiences – or ‘the way things appear to us’ (involving sound, smell, taste, and feel). We’re bound to only have direct contact with phenomena, and the real challenge is that phenomenal aspects of things may be entirely different to the noumenal things themselves (or the things as they really, truly are). According to Kant’s account, our experience of the world is organised by three conceptual frameworks: space, time, and causality. Categories such as cause and effect are like lenses that are imposed on our experiences, not derived from them. This means, we experience a world full of causes and effects, and yet, there is nothing like causality directly observable ‘out there’ in the world. Rather, it’s our way of thinking that makes us have cause and effect-type experiences (this perspective is more owing to David Hume than Kant, whose whole philosophy was aimed at fighting the scepticism this depiction created, though many don’t find his solution to the problem very convincing).

Check out the first image on this site, which uses a person looking at a table to explain Locke’s primary and secondary qualities. In Kant’s terms, the table itself is the noumena, and it’s something we only ever have contact with through the mediating and distorting role of our senses and our minds. Our actual rich experience of this table is the phenomena.

‘Phenomena versus noumena’: Phenomena are our experience of things, whereas noumena are the ‘things in themselves’, or the source of our experiences. Noumena exist independently of our experience. We only ever infer them, rather than encounter them directly. Consequently, the world of our experiences is phenomenal, and we hypothesise that these experiences are caused by a world behind our experience that we can call noumenal. That old Zen saying about whether a tree falling in the woods when no one is around would make a sound can be understood in these terms. The noumena of a tree and its falling is independent of the phenomena of sound. It would vibrate air, but if there are no ears or brains around to convert that signal to an experience of sound, the event would be silent.

To link it with our discussion of Plato’s and Locke’s ideas above, you could say that noumena can be thought of as the original things that are projected by the light of the fire onto the wall for our hapless cave prisoners to see. The images that are experienced by the prisoners in the cave are the phenomena, and these poor cave-dwellers have no way of ever knowing whether their phenomenal experiences are accurate representations of the noumena. Noumena are the original objects with primary qualities, but also with features that interact with our perceptual apparatus and give rise to secondary qualities that we experience. You could say phenomena have secondary qualities, but noumena don’t.

Naïve Realism

What have we learnt from this whirlwind tour of influential philosophical debates that concern sensation and perception? Essentially, we don’t have direct contact with the things that cause our perceptions (the noumena). Rather, our experience of them (the phenomena) are like shadowy blurry reflections cast onto a wall. Further, our experience of things is amplified to include a host of secondary qualities (taste, colour, sound, etc.) that are not really a feature of the ‘thing in itself’.

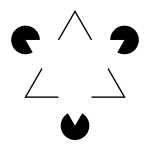

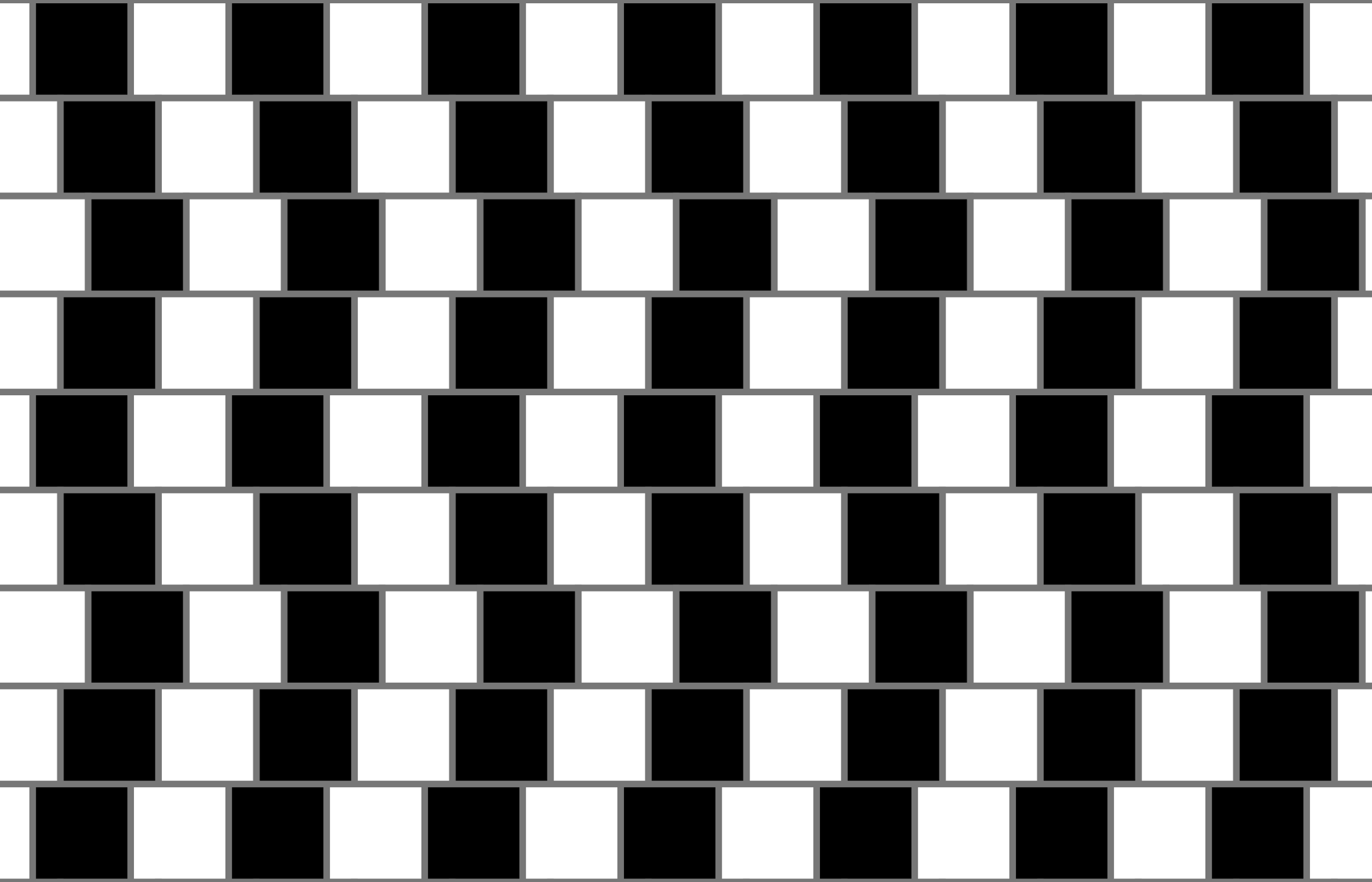

In this way, our perceptual systems have evolved over millions of years to operate similar to an augmented virtual reality system. Our brains were using augmented reality long before computer technology was advanced enough to develop something like the once-popular ‘Pokémon GO’ mobile phone game. This augmented reality is an incredible evolutionary achievement, but gets us into trouble when our perceptual experiences don’t match what is ‘out there’ being perceived. This is most easily observed (and entertainingly) when we look at perceptual illusions. For example, in the centre of the image below (Figure 3.8), you might see a downward pointing white triangle, which isn’t there at all, but is visible to you because of your augmenting top-down processing.

Perhaps in the next example (Figure 3.9), you see slanted lines? Well, there are none here, only straight parallel lines. Again, your perceptual system has allowed you to experience an augmented reality.

Without a good doze of science, psychology, and philosophy, we often have a fairly childlike commonsense (overly trusting), view of our own perceptions. We have far too much faith in them and are too easily suckered in by their many pitfalls. We are the trusting lover who keeps falling for the same lies of our perceptual system, though they regularly betray us. A version of this perspective has been called naïve realism.

‘Naïve realism’: Naïve realism is a technical term used in philosophy and psychology to represent the belief that everyday material objects (desks, recorded lectures, trees, rain, etc.) are real (the realism part) and that these things exist just as we perceive them (the naïve part). Naïve realism has faith in the existence of objects out in the world and that our sense and perception equipment give us direct and correct contact with these things. We’ve seen from our preceding discussion that while this is a fairly commonsense position, it’s rather difficult to have much certainty in it.

In simpler terms, the naïve realist believes that as we move around in the world and bump into things and these things make contact with our sense machinery (eye retinas and eardrums and the like), these things are really there and are being correctly captured by our sense organs. This assumption proves quite useful in navigating everyday life because it isn’t always productive to continually doubt what your senses are showing you. However, this perspective does leave us vulnerable to a range of misperceptions and false steps. The solution is to be aware of the pitfalls and vigilantly work to accommodate them.

Beliefs and Models

So how is it that we actually navigate and interact with the world? When we wake in the morning, and our brain starts registering the flood of electrical and chemical signals from our eyes, ears, and body, how do we even begin to organise and make sense of these? And how do we know what to do next? There is no way to predict the future, so why aren’t we paralysed with indecision, uncertainty, and anxiety? You might answer, ‘Well, that’s the job of our brain to manage all that’. And you’d be right, but we need to understand how our brains go about managing it so we can be aware of the many pitfalls and vulnerabilities involved in this process.

The solution is that we’ve built up mental representations – or working models – of the world, which we primarily interact with and rely on to understand what’s going on moment to moment (we all have our own internal versions or representations of the world). These are like maps we use that give us a sense of who we are, what resources are at our disposal, what the world is like, and how we should navigate it. Our internal representations are also predictive models that we use to anticipate events, as well as forecast the consequences of our actions. Throughout our lives, we use past experiences and beliefs to build up working models of the world that allow us to grasp its essential features and laws, and use these to make decisions and navigate life. These mental models are part of – and represent – our belief systems and worldview.

An important insight to digest here is that we don’t only interact directly with the world outside us, but process our experiences through the filter of these working models (one of many filters through which our experiences are refracted before we receive them). We live more ‘inside our own head’ than many of us actually realise. That is, our world is much more subjective and internal than it seems from our first-person perspective. We use our mental representations as a mediator between our direct experiences and our understanding of what’s happening. The way we make sense of the past, the decisions we make in the present, and the predictions and expectations we have for the future are all possible because of our internal working models of the world. These pictures or models are essential for getting us out of bed in the morning and helping us decide what to eat for breakfast. Working models contain our beliefs about the world and act as lenses that filter and shape our sense experiences. Like all lenses, our models or worldviews do a great job of focusing our perception, but also act to distort it according to a range of biases and prejudices. All lenses distort, although this is not automatically a bad thing. If lenses didn’t distort the incoming information, they wouldn’t be lenses. That’s how and why lenses work. We want and use this distorting power of lenses because it’s what allows us to see and understand things in specific ways; however, we should always be aware of the dangers and pitfalls of our lenses in shaping and corrupting our understanding of the world.

‘Model’: The term ‘model’ might not seem very technical as you likely use it in everyday speech, but it has a number of different technical meanings. You’ll come across this term again in cognitive psychology and statistics courses (if you enrol in these as part of your degree). In simple terms, models are just abstract representations that are intended to convey important information about the thing that’s modelled while sacrificing other details considered unimportant or not useful for whatever task the model is being constructed for.

Models are simplifications that summarise a select number of important things while ignoring the rest (unimportant things). Imagine a good model plane – it can successfully represent many features of a real plane (its look, shape, dimensions, colours, etc.), while excluding countless other details (probably the engine, the functionality, and the ten million bolts a full-sized aeroplane has, etc.). Cognitive models work in a similar way by using past experiences and prior knowledge to formulate a representation of the world that we can use to understand it and make predictions about it.

Look at the photograph in Figure 3.10. You can see plenty of important features have been incorporated into this model of a train, but perhaps even more features (generally those considered unimportant) have been left out –this is what makes it a model, rather than a real train.

One of the primary assumptions we make in order to piece together a useful model of the world with which to interact is that the future will resemble the past in some reliable way. This assumption works out well for us most of the time, but also gets us into trouble more times than we would like. The major strength of our mental models is also their biggest weakness: that is, that they’re always incomplete and partial. We compound this weakness when we’re rigid and inflexible in our beliefs and ideas. An important critical thinking lesson for all of us is that we need to be ready to revise our ideas of the world as new information comes in.

These cognitive models are just approximations that we build up from our own experiences – as well as our observations of others’ experiences – in conjunction with facts we’ve learned along the way. Over the course of our lives and learning, we piece together facts and beliefs that inform our models of what the world is really like, and how we should successfully interact with it. If we’re flexible and careful, the puzzle we piece together becomes increasingly flexible, refined, and sophisticated as we gather more experiences and learn more. As I’ve stated, a primary purpose of our internal working models is to give us enough understanding to make predictions or inferences about what will happen next and how we should behave. In this way, our mental models are like inference cranks we can use to pump out working theories of what is going to happen, and this allows us to make decisions about how we will behave.

It’s worth taking some time to think about our heavy reliance on these models – what we gain from them, but also the vulnerabilities they open up for us. Firstly, the use of mental models has evolved to prioritise practical utility over accuracy. I’ve mentioned this idea before when talking about the evolution of our brain, mind, and belief systems. Beliefs and ideas (features of our working models) are selected because they serve a purpose (usually to increase our chances of survival). Accuracy is rarely a consideration. It’s reasonable to think that accurate models are also likely to maximise our chances of survival, but this isn’t necessarily the case. It’s not uncommon for us to struggle to let go of false or irrational beliefs because they’re adaptive in some way – many religious and superstitious beliefs have evolved for this reason. There was an entire issue of the philosophy journal, Philosophical Explorations, entitled ‘False but Useful Beliefs’ that discussed this very issue.[10]

In eliminating a lot of the seemingly unnecessary particulars and noise (which I discussed at the beginning of this chapter) in real-world events and processes, models are intended to be idealised and filtered versions of the things being represented. Idealised here means that the model abstracts (takes away) certain features of the things being represented and considers them in isolation and as though they function in a perfect way. This is very vague, I know. Let me try explaining with examples. Suppose you’re a clinical psychologist and use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, or DSM-5 diagnostic criteria as models to define mental illness. These models serve a useful function in helping to guide you when categorising people as either ‘psychologically ill’ or ‘psychologically well’, as well as discriminating between the types of mental illness a person might have. Yet, there are very few circumstances where an individual would perfectly match a given depiction of a diagnosis in every detail. We also see models as idealisations in the fashion industry. A fashion model is expected to present an idealised view of how a piece of clothing will look. Yet, nothing I have ever put on looks anything like it did on the model (but maybe that’s just me).

Models are idealised approximations that are useful precisely because they try to eliminate noise and randomness. We need to be aware of this and be flexible in how we apply them because they don’t perfectly mirror reality (nor should they – if they did, they would be the real thing and not a model).[11] The take-home message is that we build models and worldviews up out of our ongoing experience, and then use these as ways to anticipate and interact with events. Yet models are – by design – imperfect, partial, idealised approximations that vary in their usefulness. The statistician George Box put it best when he asserted ‘any model is at best a useful fiction—there never was, or ever will be, an exactly normal distribution or an exact linear relationship. Nevertheless, enormous progress has been made by entertaining such fictions and using them as approximations’.[12] What this means is that models are idealised and partial abstractions, which are intended not to perfectly mirror reality. This isn’t a defect of models, but a powerful benefit – it’s why they’re useful. By being wrong, it means they miss things like details in the reality being modelled to focus attention on specific (and more important) features and represent these in an idealised way.

We are starting to see how raw sense information passes through multiple filters before any perception takes place. A sampling of these filters is depicted in (Figure 3.11).

Beliefs and Belief Systems

A belief is simply the acceptance of something as being true. It’s a personal position we adopt towards claims, whereby we accept them as being accurate or factual. Beliefs relate to propositions (statements that can be either true or false), which is a term we’ve come across several times already in our critical thinking journey. When somebody accepts a proposition as true, they can be said to believe in it. These beliefs can include all sorts of content. They can involve interpretations, evaluations, conclusions, or predictions. Beliefs tend not to exist in a vacuum, but come in families and are interconnected. The working models we described previously are examples of belief systems we hold on to and rely on.

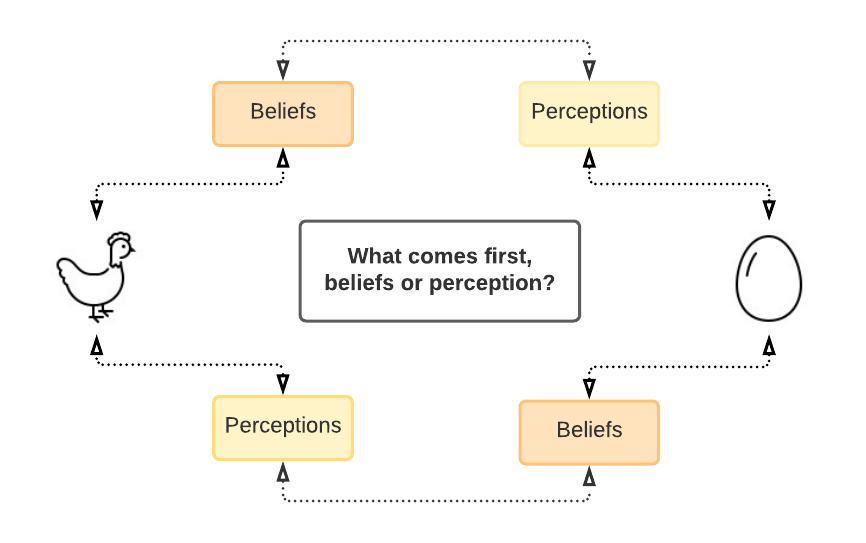

Beliefs and Sensation: A Chicken-and-Egg Problem

There’s an interesting dynamic interaction between belief and sensations. Many people hold a simplistic view that our beliefs about the world are developed out of the raw sense data they experience. But you’ve now been reading this text long enough to know that perspectives like this are far too simplistic. Our beliefs are also powerful perceptual filters and can have a decisive role in dictating what we sense. Many of our beliefs even predate sense perceptions or cannot possibly be derived from them (such as a belief in certain things like infinity).

To illustrate how beliefs impact sensations, a famous psychological experiment was conducted by Harvard psychologists, Jerome Bruner and Leo Postman, in 1949. In this study, participants were shown a series of playing cards, like the ones you use playing poker or blackjack. Most of the cards were normal, but a few of them had been altered to be anomalous (i.e. non-typical). For example, one might show a red four of spades – and yet spades cards are always black. When participants were shown the cards in a timed exposure, the anomalous cards were almost always identified – without apparent hesitation or puzzlement – incorrectly as normal. For example, an anomalous black six of hearts would be identified as the six of spades (so the colour was correct). Participants automatically and confidently claimed that what they saw seemed to always be consistent with what they believed were the ‘right’ perceptions they thought to be possible. This experiment shows how we take our beliefs with us into the world, and they act as lenses or filters through which we see things and make meaning of our experiences.

Many other experiments like this have been conducted and confirm the idea that our belief systems moderate and help produce the experiences we have. One interesting study showed that people with very strong beliefs may work harder to suppress falsifying information, and have different physiological reactions to potentially threatening information.[13]. Because our sense experiences require so much top-down input to be meaningful, it’s always inherently ambiguous (like anomalous playing cards). This ambiguity is the royal road to confirmation bias (discussed below). However, as with most things in this book, there’s an upside. Ambiguity is also an invitation to creativity, and is a great antidote to dogmatism. Relish ambiguity!

Thomas Kuhn, a famous historian of science who reported on the playing card experiment in his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), went so far as to claim that people with different worldviews (i.e. different belief systems, though he liked to use the word paradigm), actually inhabit different worlds. People inhabiting different worlds produced by their worldviews or lenses can look at the same scene and see different things. He even went so far as to say that people inhabiting these different worlds would find it nearly impossible to communicate effectively, as they would always be talking past each other and take words to mean different things. To hold a different worldview isn’t merely a theoretical thing – it’s to actually see, hear, taste, and be in the world as a fundamentally different place. The world we experience changes radically as our worldviews shift. It’s a much more tangible thing.

This is a rather extreme view, but it does carry an important insight. We can see how people with radically different worldviews would (at least from their subjective first-person perspective) seem as though they’re inhabiting different worlds. This can be an important thing to keep in mind when we are trying to talk to people of different cultures, religious persuasions, or different political beliefs who might have radically different worldviews to us.

As I alluded to in Chapter 2 when discussing scepticism, it’s very difficult for us to move ourselves or others beyond a worldview that’s held dear. In a way, we become devoted to worldviews, just as if they were religious beliefs (the same is true of our core concepts). We have an enormous emotional investment in assuring our thinking is only pushed in a direction our concepts and worldview are already taking us. Just as it can be psychologically devastating for people to lose their religious faith, the same can be true of losing faith in one’s worldview or core concepts. Concepts are the building blocks of someone’s worldview, and when these are challenged, their very idea of themselves and the world they live in is at stake.

So, we have a chicken-and-egg situation, just as I depict in Figure 3.12. Beliefs dictate what sensations and perceptions we have and how we process them. In turn, our perceptions influence what beliefs we hold (we’ll see in Chapter 5 that concepts have a similar function). Consequently, we view the world as already fitting approximately within our belief structures, as conforming to our pre-existing worldview, and confirming the conceptual categories that we already hold dear. This is concerning, as it shows we’re resistant to – or not even aware of – perceptions or experiences we encounter that could potentially falsify our beliefs and worldviews. This is an enormous liability in the way we think and interact with the world, and one we have to consciously struggle against. Therefore, being a skilful thinker means adopting the right attitudes towards our beliefs – something we’ll discuss below. This tendency to favour – and even shape – perceptions so they’re consistent with our core beliefs is a cognitive bias called confirmation bias.

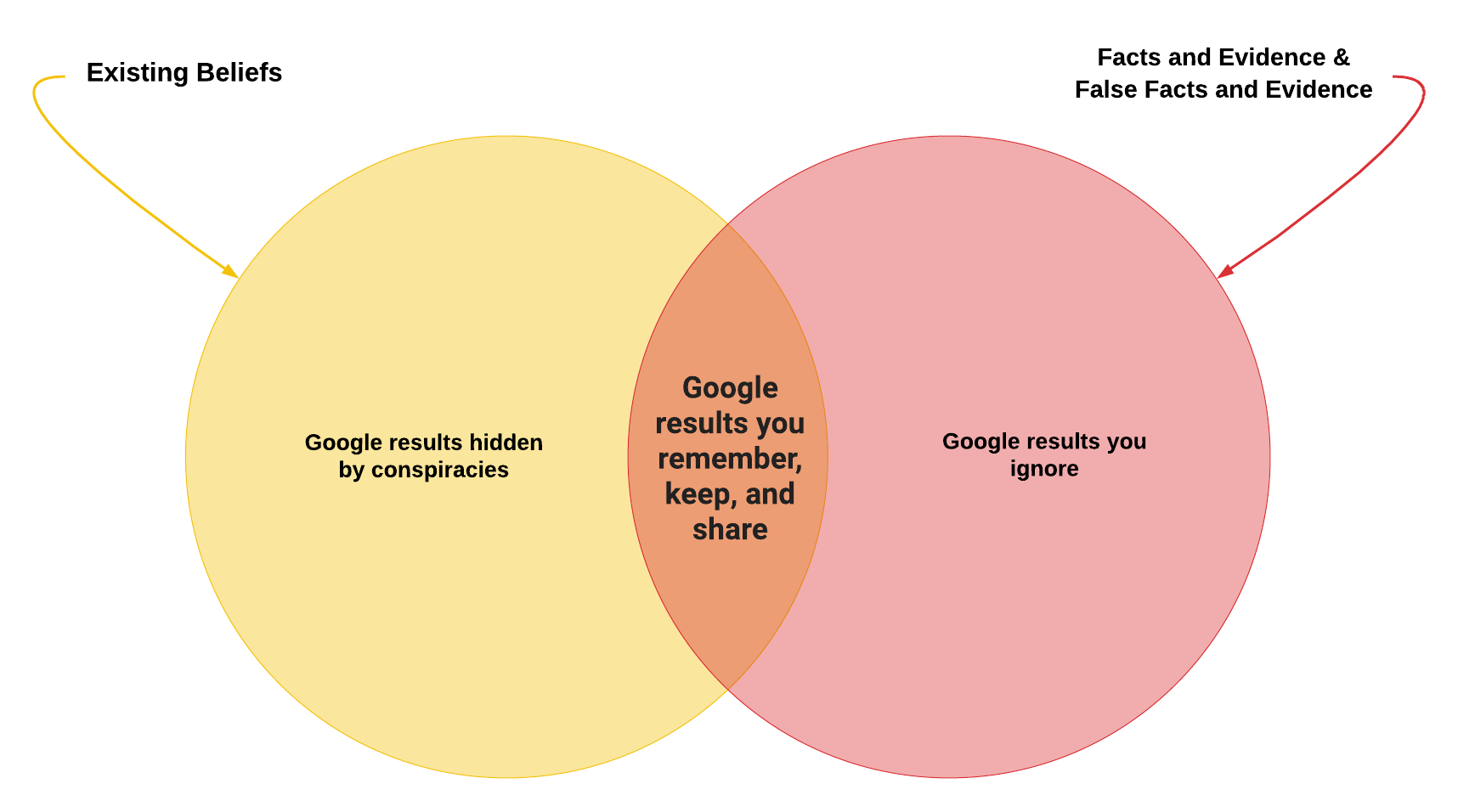

‘Confirmation bias’: Confirmation bias is one of a number of well-known cognitive and perceptual biases. This cognitive bias has been known for so long that even the Ancient Greeks talked about it.[14]. We all have a tendency to search out, notice, attend to more closely, accept uncritically, and remember information that confirms what we already believe. That is, information that confirms and supports the things we believe in is more likely to be looked for, noticed, accepted, and remembered (see Figure 3.15). In fact, because of our distorting perceptual, linguistic, and thinking lenses, pretty much any experience can be confirming. Ultimately, all interpretations are both self-serving and belief-serving since all experiences must undergo interpretation, and interpretation invariably serves our own beliefs and expectations.

Let’s look at an example. If you tell me something you believe, and I inform you it isn’t true, the first inclination you’ll have is to go find evidence to prove me wrong. This is the exact opposite of what you should be doing. We then take the opposite approach to how we treat information that isn’t consistent with our existing beliefs. We tend to avoid, ignore, overly criticise, and forget non-confirming evidence. Like with all cognitive biases, we need to be aware of this tendency and actively struggle against it as much as possible. The best way to do this is to always focus on trying to falsify our beliefs and not to try to confirm them (more on this falsification attitude below).

As is often the case with critical thinking, Francis Bacon (1561-1626), got there first and articulated these issues as well as anyone could:

The human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion (either as being the received opinion or as being agreeable to itself) draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or else by some distinction sets aside and rejects; in order that by this great and pernicious predetermination the authority of its former conclusions may remain inviolate.[15]

Structure of Belief Systems

As I mentioned earlier, individual beliefs don’t exist in isolation, but are part of integrated and interdependent systems (like networks or webs). By ‘integrated’, I mean these beliefs fit together in a mostly cohesive network (we tend to resist holding contradictory beliefs), and by ‘interdependent’, I mean the credibility of each belief rests on a large number of other beliefs being true. In simple terms, beliefs or propositions about the world are ‘holistic’, which is an important insight primarily due to the work of logician Willard Van Orman Quine.

‘Holism’: These days holism and holistic are trendy catchphrases hijacked by peddlers of pseudoscience, and as a result, these words have lost much of their meaning. Holism refers to systems where parts can’t be understood in isolation, but must be considered in light of the whole. That is, the parts that make up something holistic can’t be understood when looked at alone, but only by considering their interconnectedness with other parts of the system. For example, holistic medicine seeks to treat the whole person, considering mental and social factors rather than just the symptoms of a disease.

Beliefs are structured in a holistic way as ‘webs’ (another metaphor presented by Quine), with the beliefs that are core to our worldview or that we’re most committed to in the centre so they’re better fortified against falsifying evidence. As holism and the web metaphor imply, specific beliefs rely on (and imply) a host of other beliefs to support them. If I hold a belief in a 6,000-year-old planet (as many fundamentalist religious people do), then I’m also committed to a variety of other beliefs about the fossil record, evolution, and cohabiting humans and dinosaurs, etc. Some beliefs we’re committed to just by implication, and we might not even be aware of them until they’re pointed out. Even though we might think we’re open-minded, we all have beliefs that we’re not willing to give up easily. When we confront evidence that disconfirms our beliefs, we can choose to offer up a less important belief (on the periphery of the web) as a sacrificial lamb, and retain those beliefs at the core of our worldview that we consider most precious.

So, our belief webs have a type of hardcore group of beliefs that need never be revised. Surrounding this hardcore is a protective belt that contains a range of auxiliary beliefs that we can throw away to protect the hardcore from falsification. Beliefs in the hardcore are protected for a number of reasons, but often because they’re essential to our broader worldview, and the upheaval to our worldview by rejecting them could be quite traumatic. Our core beliefs are so cherished as to become sacred cows that we worship, and won’t allow them to be killed even when overwhelming sense and evidence stands against them. Confirmation bias is just one of many devices we wield to protect these sacred cows.

Let’s flesh this out with an example. Perhaps I have a belief that the moon landing was faked. I’m very committed to this belief, as it’s quite central to my broader worldview (perhaps one about governments being corrupt and deceitful). Regardless of my motivations, I have deeply held beliefs about the faking of the moon landing. Therefore, when someone presents me with satellite images of footprints on the moon, I can choose to revise the core belief about the faked space mission, or I can choose to drop another peripheral belief that I’m not so committed to. In this case, I might respond by changing my mind about the accuracy and reliability of satellite imagery (something which I had no reason to doubt before). With an almost infinite number of ‘moves’ like this up our sleeve, we can fortify almost any belief against revision.

Appropriate Attitudes About Beliefs

With all that we’ve learned about how beliefs form and are structured, as well as what tactics we might unwittingly (or intentionally) employ to protect certain beliefs, we should now be sufficiently motivated to avoid the pitfalls our beliefs can lead us into. To achieve this, we need to adopt a specific type of stance in relation to our beliefs. Again, like the list of critical thinking attitudes I discussed at the end of the last chapter, this isn’t intended to be a complete list, just an overview of some safer ways to relate to our beliefs.

Modesty

The first necessary attitude (which should be obvious by now) is that we need to approach our own beliefs with a good dose of modesty. After progressing through this chapter, several facts should be apparent to you:

- We don’t know nearly as much as we think we know.

- Our beliefs are built on sense and perceptual foundations that are far shakier than we often realise.

- We have only very indirect and filtered or augmented contact with the outside world.

- We (sometimes unconsciously) employ a range of devious manoeuvres to protect beliefs we are very attached to.

- We can (and might) be wrong about every belief we currently hold.

Unfortunately, most of us don’t possess any modesty about our own beliefs, and this gets us into a world of trouble. Quine, borrowing an old Biblical expression, famously pointed out that longing to be correct is a ‘pride [that] goes before destruction’ since it prevents us from knowing when we are wrong and impedes the advancement of knowledge. [16].

We should hold all our beliefs as nothing more than rough estimations that we simply haven’t falsified yet. We only ever have access to partial – and potentially biased – information (most information is provided to us to support someone else’s agenda), so we have no right to any sense of certainty about what we believe. Unfortunately, like an insecure lover, it’s not enough for us to simply have beliefs – we’re obsessed with feeling certainty about them. Unless we’re skilled at critical thinking, we simply can’t and won’t tolerate uncertainty. We’ll always choose to lean on bad information, even knowingly, rather than suffer the anxiety of ignorance. Being modest will help to ensure we’re open to being wrong and reduce the impact of confirmation bias. This attitude is also critical for social progress, since certainty always destroys tolerance (those who are the most certain in their own ideas are always the least tolerant to conflicting ideas).

Falsifiability and Intellectual Courage

Let’s reiterate two key points from above. Firstly, we should never forget that our beliefs are just our best guesses. They’re nothing more than approximations. The next thing to keep in mind is that confirming evidence for almost anything is cheap and easy to find, and even misses the point entirely. Scientific evidence that’s of any worth is evidence that has been collected while trying to falsify a proposition, and has simply been unable to do so. The same is true of our everyday beliefs and perceptions.

There are very good logical reasons why confirming evidence isn’t even a very useful way of supporting beliefs, and that only disconfirming evidence has the proper logical relationship with propositions, but we’ll go over that in more detail in Chapter 6. In this chapter, it’s more important to consider the power of confirmation bias when looking at evidence that either supports or falsifies our beliefs. This emphasis on attempting to falsify or refute beliefs or propositions is known as falsifiability.

Explanation Box – ‘Falsification’: (I know we’ve gone over falsification before, but it’s critical for understanding the role of evidence, and it’s also one of the concepts students typically struggle with, so I’m going to recap it for you).

Falsification is just the approach to evidence that focuses on how evidence can contradict ideas and claims. This approach focuses on disproving propositions and doesn’t see much value in trying to accumulate evidence supporting them. The most powerful presentation of this approach was by Karl Popper in his book, The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934). Popper claimed the only way to scientifically test a theory was to try and prove it wrong. Confirmation (or the act of trying to gather evidence to support a belief) is fraught with psychological and logical problems, and therefore, he claimed it was unscientific. For example, as we’ve seen from our cognitive biases above, we’re far too good at searching for confirming evidence. Falsifying claims is usually much easier anyway. For example, to support the claim that ‘Swans are white’ requires us to make millions of observations of swans (we haven’t really confirmed anything until we see all of them). Falsifying that claim is as simple as finding one black swan. There are a host of more technical problems with the confirmation approach that we ‘ll get into later in this text, but for now, it’s important to keep in mind that confirming evidence is almost never conclusive in the way that falsifying evidence is. For example, finding another white swan isn’t very conclusive if we’re trying to show they’re all white, whereas finding one black swan quickly and easily throws the proposition straight in the trash.

We should be sceptical of all of our beliefs and not take confirming evidence too seriously. We need to be mindful of our emotional and psychological attachment to certain beliefs, and our tendency to protect them from falsification. If you really value having true beliefs, then you should have the courage of your convictions and try hard to look for disconfirming evidence. This takes vigilance and resilience, as it can be devastating to have views you’re attached to be falsified. We should be willing to stand with the courage of Immanuel Kant, who wrote, ‘If the truth shall kill them, let them die’. (Here we can interpret him to mean our beliefs, assumptions, and ideas.)

The opposite of this is intellectual laziness or timidity. We should be bold and try to sacrifice any of our preciously held beliefs. These are not inconsequential issues, and these attributes could save your life one day.

Openness and Emotional Distance

We need to be open to the weaknesses that our perceptual and belief systems suffer from: open to the idea that we could be wrong about what we sense and perceive – and by extension – about what we believe, open to the biases we employ to reinforce our beliefs from falsification, open to the search for falsifying evidence, and always open to change. Being open to ideas that oppose our own is a distinguishing mark of being a mature human being as well as a skilled critical thinker. When we lack openness, we deny nuances to the ideas that oppose our own. For example, the cultural right caricatures the cultural left and vice versa, and both then cherish their comforting fictions.

Emotional distance from our beliefs is an important attribute that will enable us to be open to the prospect that our ideas and beliefs are wrong, and reduce our emotional resistance to falsifying information. No one likes to be wrong or to find out we believe something that’s actually false. We can reduce the pain of these experiences by continually trying to falsify our beliefs in order to root out incorrect ones. We can also reduce the pain of being wrong by cultivating some emotional distance from our beliefs, especially those that are core to our worldview.

Take‐Home Message

Granted, this chapter was a little dense, and not particularly applied. Think back to Chapter 1, when I discussed the steps, we must progress through to become a skilled thinker. The first of these was examination and understanding. An important part of this is understanding our own state of thinking, and the way to do this is through self-reflection and awareness. With this in mind, this chapter has covered a lot of essential ground that illuminates for us how our senses and perceptions operate, how they influence our beliefs, and how our beliefs and approaches to processing in turn influence our perceptions. Being aware of this is the first step to becoming a better and more critical thinker. Primarily, this journey begins by being more critical and analytical with respect to our perceptions and beliefs. With all the problems I discuss with beliefs, you might be wondering, ‘What’s the point of having any beliefs?’. Well, we can’t just choose to believe in nothing because unbelief is inaction and in our Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’ world, inaction is death. So, the challenge is to think carefully about how we should come by our beliefs, and how we should then treat them. Naively assuming that our beliefs are true is obviously our default position (and therefore, the most popular stance to take), but also the most dangerous and difficult to justify. Following this chapter, I expect (hope) you’re feeling a little humbler about the accuracy and usefulness of your own perceptions and beliefs, but I also hope you feel more optimistic about your ability to improve and overcome many of the limitations we discussed. Onwards and upwards!

Additional Resources

By scanning the QR code below or going to this YouTube channel, you can access a playlist of videos on critical thinking. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content. URL links to module 2. You can access a cognitive flashcard deck and additional online video related to this chapter using the links below:

- Cognitive Bias Flashcard Deck (you can get any business card printer to print them for you)

- The role of belief in interpretation

- Kindt, M., Van Den Hout, M. Selective Attention and Anxiety: A Perspective on Developmental Issues and the Causal Status. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 23, 193–202 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010921405496 ↵

- Laufer et al. Behavioral and Neural Mechanisms of Overgeneralization in Anxiety. Current Biology, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.023 ↵

- The answer is the card with the number 8 and the green card ↵

- Jason, J. (2017, August 10). Confirmation bias making you dumber, and what to do about it. Medium. https://medium.com/@umassthrower/confirmation-bias-sucks-a7bc989d3fd2 ↵

- You can create your own stereogram online using this Easy Stereogram Builder. ↵

- Paul, M., Lech, R. K., Scheil, J., Dierolf, A. M., Suchan, B., & Wolf, O. T. (2016). Acute stress influences the discrimination of complex scenes and complex faces in young healthy men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 66, 125–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.01.007 ↵

- Republic, VII 514 a, 2 to 517 a, 7 https://web.stanford.edu/class/ihum40/cave.pdf ↵

- I don’t want to give too much credit to Locke for originating this idea, though he produced the most famous discussion of it: ‘Though Boyle and Locke invented and popularised the distinction and the terminology of primary and secondary qualities, the distinction dates back in principle to Democritus, who said that sweet and bitter, warm and cold, and colour exist only by convention (νόμῳ), and in truth there exist only the atoms and the void (Fr. 9, Diels and Kranz). The distinction was revived by Galileo Galilei and accepted by René Descartes, Isaac Newton, and others.’ Cengage. (n.d.). Primary and secondary qualities. Encyclopedia.com. https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/primary-and-secondary-qualities ↵

- See Book II, Chapter VIII ‘Some further considerations concerning our simple ideas of sensation’, or for a summary, read the SparkNotes study guide. ↵

- Bortolotti, L., & Sullivan-Bissett, E. (Eds.). (2017). False but useful beliefs [Special issue]. Philosophical Explorations, 20(Suppl. 1). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13869795.2017.1287290 ↵

- This is true even of scientific laws. For example, the laws of physics are an idealistic abstraction that don’t actually correspond to anything in real life. An influential book on this topic, How the Laws of Physics Lie, was published by Nancy Cartwright in 1983. The main message here is that abstract idealisations we call scientific laws attempt to describe regularities, but never act in isolation in the real world, and there are too many variables and too much randomness in real life for them to really correspond to anything. Some physical laws acknowledge this in their name, such as the ‘Ideal Gas Law’. ↵

- Box, G. E. P., & Luceño, A. (1997). Statistical control: By monitoring and feedback adjustment. John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- See Reiss, S., Klackl, J., Proulx, T., & Jonas, E. (2019). Strength of socio-political attitudes moderates electrophysiological responses to perceptual anomalies. PLoS ONE, 14(8), Article e0220732. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220732 ↵

- Greek war general, Thucydides, (c. 460 BC–400 BC) wrote, ‘For it is a habit of humanity to entrust to careless hope what they long for, and to use sovereign reason to thrust aside what they do not fancy’. ↵

- From The Novum Organum, fully "New organon, or true directions concerning the interpretation of nature") or Instaurationis Magnae, Pars II ("Part II of The Great Instauration"), 1620. ↵

- Quine, W. V. O., & Ullian, J. S. (1970). The web of belief. Random House. ↵