Chapter 2, Part B. Critical Thinking in Depth: Stages, Steps, and Dispositions Continued

Learning Objectives

- Appraise scientific methods and evidence

- Detect formal and informal fallacies in arguments

- Be clear on how decisions and values impact every step of critical thinking

- Understand the importance of scepticism, inquisitiveness, open-mindedness, and introspection or insight

New Concepts to Master

- Evidence

- Falsification

- Bias

- Empirical

Steps Necessary to Becoming a Critical Thinker (Continued)

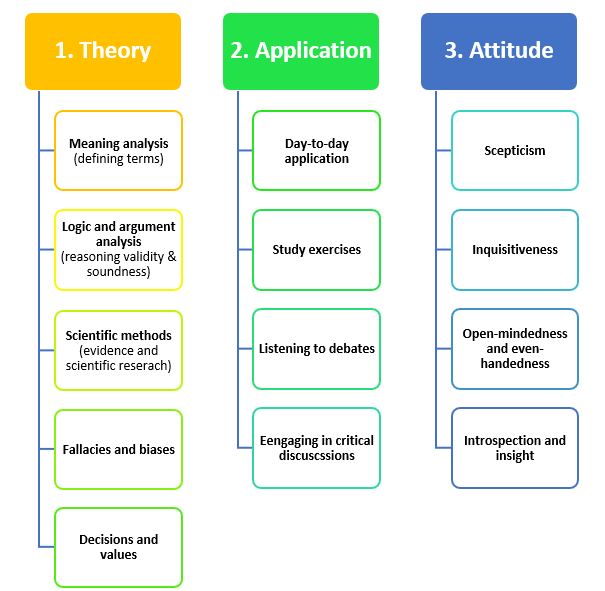

Recall Figure 2.4 which outlined critical thinking attributes covered in Chapter 2. In Part A of Chapter 2, we got through ‘Meaning Analysis’ and ‘Logic and Argument Analysis’. Part B will follow on from this point, starting with ‘Scientific Methods’.

Scientific methods

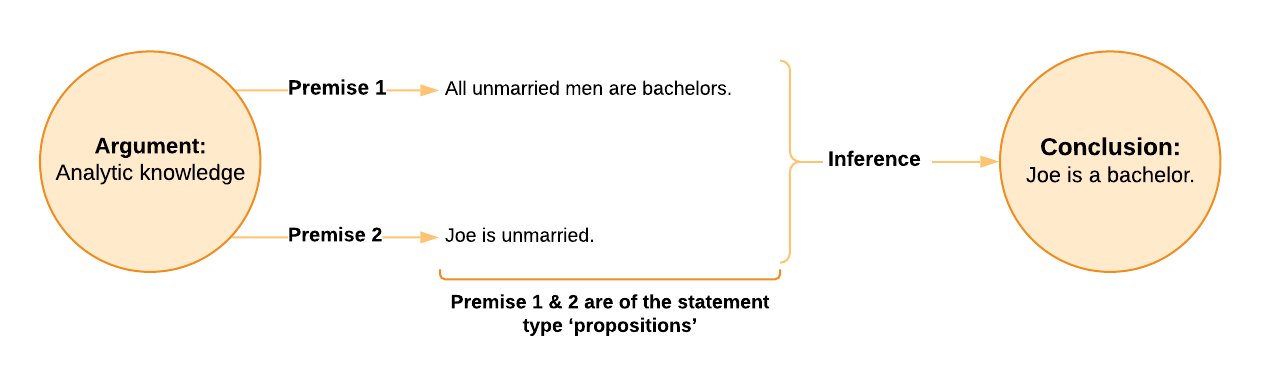

Coinciding with the appraisal of reasons when scrutinising any claim must be the ‘appraisal of evidence’. Not all arguments contain premises that appeal to evidence (this type of argument is about what we call analytic knowledge – we’ll learn all about this type of knowledge in Chapter 4).

Let’s look at an example:

This argument’s first premise is merely definitional or a ‘truth of reason’. We call this type of definitional knowledge, analytic (more on this in Chapter 4). The second premise might only require some evidence and validation of the fact that we don’t truly trust Joe (this is what is referred to as a synthetic proposition – more on this later). But overall, this argument can be appraised on the basis of meaning and reasoning alone. Both premises are true (at least for the purposes of our fictitious example), and the inference to the conclusion from the premises is valid so, without any evidence at all, we can determine we have a deductively sound argument. However, evidence plays a major role as part of the premises for most arguments we encounter in everyday life.

Many different things can count as evidence – such as facts presented in a criminal trial – but the evidence that will concern us most is scientific evidence. The term ‘evidence’ is usually used to mean observations about the world that are consistent with – and, therefore, corroborate – a specific claim. For example, if I have a claim that ‘All my critical thinking students have above-average intelligence,’ and I collect observations on everyone’s IQ scores to show that they’re all above average, these observations (the scores) are counted as evidence that can support my claim. But as we’ve learned before, not all observations are equally convincing. For example, it’s far less convincing if I collect evidence about the students’ intelligence from just chatting to one or two of them, which isn’t a very scientific way of testing my claim. As you might be able to guess, the most convincing way to collect evidence is using scientific methods.

Like many of these sub-topics for this chapter, detailing scientific methods is an enormous enterprise and deserves whole courses of its own. If you’re studying psychology programs, you’ll be completing many such courses that will cover the methods and processes of scientific methods. However, the most important thing to start out appreciating, is that your scientific literacy is foundational to your critical thinking skills. Scientific methods are the most powerful knowledge generation and knowledge testing system ever developed.

We can think of scientific methods as a group of techniques that have shown in the past to produce and corroborate reliable claims about the world. Reliable isn’t the same as true. Unfortunately, we can never get anything so comforting as certainty or ‘truth’ about the world, but we can produce useful and reliable knowledge. Reliable means the claims are backed up by a variety of evidence, that the evidence is repeatable, and can be used to generate new predictions about the world. However, even after satisfying all of this, scientific claims often turn out to be wrong. Remember, the basis of arguments is propositions, which are declarative claims about the world. The best method for producing and testing these types of claims is with scientific evidence. This means, if propositions are to be believed, they must be backed up with evidence, and strong scientific evidence is the most reliable form.

Even among scientific methods, there is variation in how convincing a piece of evidence is. Not all scientific evidence is created equal, and you need to carefully consider the credibility of the scientific methods used to gather evidence as you go about appraising propositions. Scientific studies can be flawed in a thousand different ways, and these flaws can disqualify the results produced by these studies. Evidence should come from the most rigorous scientific methodology available. There is lots of information available on how to rank or prioritise different scientific methods. For clinical research, some agencies like the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) have produced hierarchies of evidence that rank methodological designs according to their strength, which just means their vulnerability to bias and error.[1] You should familiarise yourself with these types of resources to improve your critical thinking and be better equipped for your career.

Evidence produced by shoddy research practices is useless. Actually, it’s worse than useless since it can be distracting and even harmful. Inconclusive studies get published all the time –even I’ve been responsible for some. But just because something is written in a scientific study and published in a scientific journal, doesn’t mean it’s credible. In fact, even with the best methods, no scientific study is perfect and conclusive in its own right, so we often look for independent replication of findings. Replication is one of the main safety nets of the scientific enterprise. This means any discovery is provisional and merely hypothetical until several different groups of scientists using their own methods can corroborate it.

When appraising evidence for propositions about the world, look for rigorous scientific studies that use the best methodologies in their field (there are some useful online cheat sheets and guides for spotting bad science). Also, never rely on only one study, since it’s only the full body of scientific evidence that achieves the reliability and credibility that we need, not any individual research finding. No single study is ever conclusive on its own. Another key point in your search for evidence relates to what you should actually be looking for. The most powerful mechanism in the scientific endeavour is ‘falsification’, not ‘confirmation’. This means you should always focus your search on – and pay particular attention to – disconfirming evidence, and never go looking solely for confirming evidence. Confirmation is easy to find, it’s cheap, and is always uncertain. The logical reason for this is that falsifying claims can be based on sound deductive logic, whereas using evidence to confirm claims relies on weaker inductive reasoning, which is logically flawed, but necessary (more on this in Chapter 6 when we discuss modus ponens and modus tollens as reasoning tools). Researchers and critical thinkers should always be trying to falsify their hypotheses and theories, not protect them. Propositions are held as working hypotheses only because they have not been falsified yet.

‘Falsification’ is an approach to testing scientific theories and hypotheses (which are special types of empirical propositions) that focuses on trying to show they’re false, rather than trying to show they’re true. The most logically valid approach to conducting science isn’t to attempt to confirm hypotheses and theories, but to attempt to collect evidence that refutes them. This theory of science was developed and popularised by philosopher Karl Popper. According to this approach, science isn’t concerned with looking for confirming evidence for its propositions, but rather, looking for evidence that falsifies these propositions. The main reason for this is to eradicate a detrimental reliance on inductive reasoning (we’ll go over these issues in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7). The falsification approach is entirely deductive. Don’t worry if you don’t fully grasp this yet – we’ll cover it in agonising detail later. The takeaway point here is that the falsification approach is entirely deductive and, therefore, logically sound. Confirmatory approaches to scientific evidence are inductive and, therefore, faulty.

A solid scientific approach emphasises falsification of propositions. Scientific hypotheses – which are empirical propositions – must be falsifiable to even qualify as ‘scientific’. Ideas that are unfalsifiable are outside the scope of science. This makes science a somewhat restricted tool for assessing these very specific types of propositions (empirical ones that are falsifiable). One downside to bear in mind when thinking about the world of science and scientific knowledge in our lives, is that it’s often unfalsifiable claims – the meaning of life, the nature of love, life after death, and the values and morals we choose to live by – that are the most important ones to us.

It’s a popular rhetorical tactic to claim to have the ‘science’ on your side when discussing ideas with those who might disagree with you. Science is very easily hijacked to serve ideological interests because scientific results are almost always ambiguous, and evidence can very easily be cherry-picked to support one side of a debate or the other. The public’s faith in the credibility of science is regularly hijacked by political, religious, philosophical, and commercial ideologies. For example, left wing progressives criticise right-wing conservatives as anti-science due to their stance on climate change, green energy, stem cell research, etc. Likewise, right-wing conservatives criticise left wing progressives as anti-science due to their stance on genetically modified organism (GMO) technology, nuclear energy, (traditional) vaccine safety – though these positions appear reversed for the COVID-19 vaccines, etc. Christian religious fundamentalists use ‘science’ to give a veneer of credibility to various ‘creationist’ accounts of biological history. Commercial interests regularly use claims of ‘science’ and ‘research’ to help sell their products (e.g. the bogus unrealistic claims of health food products, diet scams, and beauty products).

All scientific evidence is subject to scrutiny and can be interpreted many different ways. For this reason, you should continually look for the raw evidence, not someone else’s interpretation of a study (just see how the evening news routinely butchers scientific findings) and critically appraise the quality (credibility) as well as the quantity (amount) of evidence for and against a specific claim.

One last comment I want to make about the use of scientific evidence in thinking and discussing ideas relates to the notion of ‘scientific consensus’.

‘Scientific Consensus’: You’ll often hear the phrase ‘scientific consensus’ thrown around in debates about controversial topics like climate change or vaccine safety. It’s typically used to imply widespread agreement among scientists, as if truth were determined by a popularity contest of opinions. While common usage often dictates the meaning of a term, even if it’s flawed, the conventional understanding of scientific consensus as a mere headcount is misleading and ultimately weak.

The true power of scientific consensus doesn’t lie in the number of scientists who hold a belief, but in the weight of evidence itself. It’s the consensus of rigorous scientific research, data, and analysis that matters, not the consensus of scientists’ personal opinions. After all, scientists are just as susceptible to biases, groupthink, and errors in judgement as anyone else. History is full of examples where the scientific consensus was proven wrong. For centuries, the theory of phlogiston, a fire-like element believed to be released during combustion, was widely accepted. Similarly, the miasma theory, which attributed diseases like cholera to “bad air,” was the prevailing medical understanding for centuries. And even the concept of luminiferous aether, a hypothetical medium thought to carry light waves, was once firmly established in the scientific community. Yet, all these theories were eventually overturned by new evidence and paradigms.

For instance, the claim “97% of climate scientists believe humans contribute to dangerous climate change” might sound persuasive. But the truth of climate change isn’t determined by a show of hands, but by the overwhelming evidence accumulated through decades of meticulous research. Relying on what scientists believe, rather than the evidence itself, is a lazy shortcut that can lead us astray.

In our society, we often idealise scientists, mistaking their consensus for the consensus of evidence. However, critical thinking demands we don’t fall for this trap. Our beliefs should be guided by the best available evidence, not the sway of popular opinion, even if it’s shared by experts.

The distinction between these two types of consensus is crucial. It’s the difference between relying on the authority of individuals and relying on the strength of evidence. In the pursuit of truth, it’s the evidence that ultimately matters.

Training your scientific literacy is a lifelong endeavour and involves familiarising yourself with scientific methods, their underlying logic, their relative strengths and weaknesses, and their implications for propositions – how the available evidence bears on claims about the world. Knowing what counts as evidence and the degree to which that evidence can be relied upon is central to critical thinking. These skills can take years of practice, but it’s very much worth learning.

Fallacies and Biases

A major task in the scrutinising of reasons and evidence is the ‘appraisal of errors in reasoning’. This goes hand in hand with the appraisal of reasons and appraisal of evidence. By now you’ve realised that these key areas of Lau’s ‘Theory’ – or developing knowledge – (meaning analysis, logic and argument analysis, scientific methods, fallacies and biases, and decision and values) are not sequential steps, but spill into each other and are complementary ways of doing similar things. I’ve presented them separately like this, as different areas, so they each get the right amount of emphasis. As you’ve seen, propositions – the building blocks of arguments – (the focus of appraisal area two) have no meaning without careful study of definitions and terms (appraisal area one), and the appraisal of arguments involves dedicated attention to reasoning validity and soundness (appraisal area one). as well as evidence and scientific research (appraisal area three). Finally, mistakes in argument soundness and validity invariably involve screening for fallacies and biases (appraisal area four), and so on and so forth… all very inbred…

This chapter will deal mostly with fallacies. Chapter 3 covers biases in more depth. I’ll introduce the concept here because it plays an important role in this appraisal step, as well as the previous one (assessing scientific evidence).

‘Bias’ is something like a distorted or skewed view or understanding of things. A bias is like driving a car that has one small and one big wheel on the front. The car will continually pull or veer to the side with the smaller wheel – and this would be equivalent to having a bias that pulls in that direction. In this way, to be biased is to have a tendency to be pulled (usually by filtering and giving unequal consideration) to certain perspectives, evidence, interpretations, conclusions, or ideas. Biases colour our evaluations of things and sway our conclusions and judgements. While biased thinking is almost always erroneous thinking (it’s a departure from objective truth), some biases can be productive if they aid us in making rapid (albeit very rough) decisions, but they can also be deeply flawed and impair clear thinking and judgement. Cognitive biases are an example of ways our thinking might be swayed to see the world a certain way and favour certain perspectives that might be useful in saving time, but can wreak havoc – just like driving a car with one smaller front wheel. Chapter 3 and Chapter 7 will deal at length with cognitive biases.

Our brains and minds come preprogrammed with a host of these unbalanced wheel sets. It’s unlikely we can eradicate all the biases we are prone to, but we can become aware of them and compensate for their effect, in the same way the driver of the car with uneven wheels can continually pull the steering wheel in a way that counterbalances the bias. Ongoing awareness and counteracting biases are part of the daily challenge for critical thinkers.

A note on perspectives and bias: All perspectives bias or colour perception and communication in some way. Perspectives are always partial, narrow, and filter our experience and communication (we’ll learn a lot about our filters in the next chapter). Importantly, there is no perspective-free standpoint from which to view the world and communicate about it. So, every perception you have is from a perspective, and therefore, partial, narrow, and biased in some way. Similarly, every expression or communication you share or are exposed to is from a perspective, and therefore, partial, narrow, and biased in some way. These biases are not always malicious or even intentional, but are nonetheless influential. To not occupy a perspective is to not exist. To not communicate a perspective is to not communicate at all.

This helps explain why two people can witness the same event and still see different things. It’s also why news media reporting on the same event can give radically different interpretations of it. For these reasons, there is no point looking for bias-free news or information because none exists, none could possibly exist. We can reduce the influence of our perspectives and biases by becoming aware of them and mitigating them as much as possible, but we can never remove them. The best way around the influence of our narrow perspective is to expose ourselves to as many perspectives as possible; especially those we disagree with or contradict our perspective. Perspective-taking is an essential skill in critical thinking, so work hard to try adopting and experiencing as many perspectives on an issue as possible. This perspective-taking is a creative act that requires self-awareness and imagination, and as usual, lots of practice.

We call errors in reasoning ‘fallacies’. Therefore, to commit a fallacy is to make a mistake in your reasoning. Fallacies are the cancers that live inside bad arguments. They prevent a conclusion from being drawn from premises. The most common reason an argument is unsound is because it’s fallacious. An invalid logical argument (recall our discussion of logical validity before) is a fallacious one.

Fallacies are usually grouped into two types: formal and informal. Formal fallacies contain a problem with the structure of the argument itself: its ‘form’. Whereas, an informal fallacy contains a problem with both the form and the content of the argument. When the conclusion does not arise in a rational way from the premises, a fallacy has been committed. Whether the fallacy concerns what the premises say or how they say it is the difference between an informal versus formal fallacy.

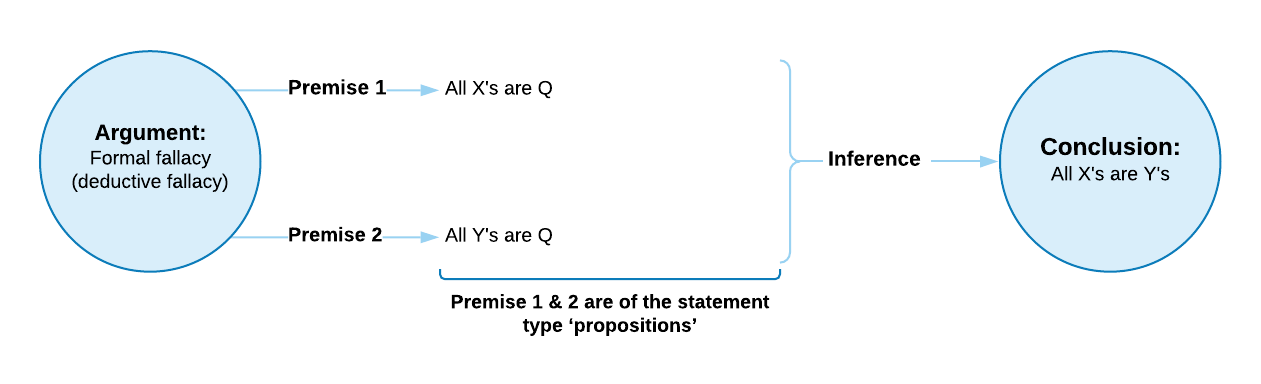

Consequently, formal fallacies involve how the propositions in the premises licence the proposition in the conclusion. It has to do with how these are laid out, which is to say, how the argument is put together. If an argument is put together properly, the conclusion is forced logically from the premises without any ambiguity or formal fallacy having been committed. We’ve come across formal logical fallacies above in our discussion of deductive arguments, which were considered valid (that is, without any fallacy) if the conclusion ‘must’ be true when the premises are ‘true’. We learned that a common formal fallacy seen in deductive argument is the non sequitur.

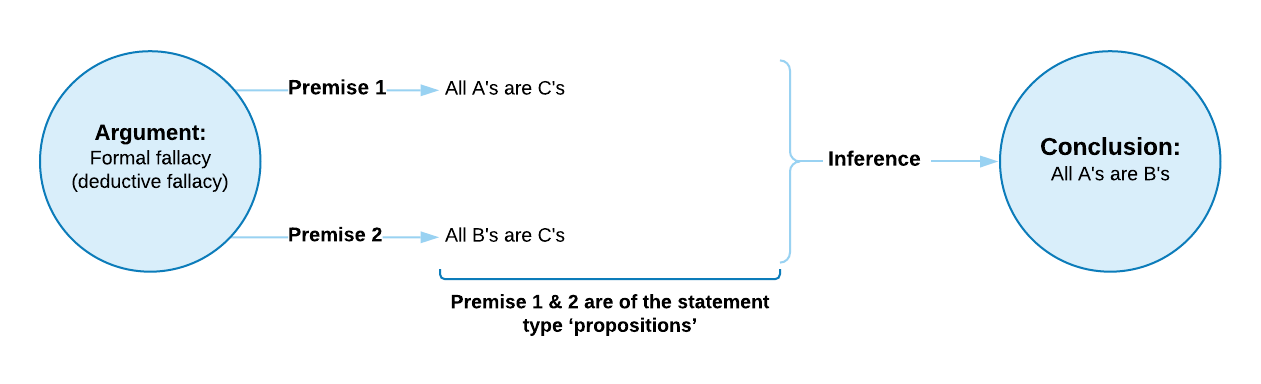

‘Formal fallacy’: As the name implies, formal fallacies involve a problem with the structure or ‘form’ of the argument, which is to say, how the propositions connect to each other. In contrast to informal fallacies, these problems have nothing whatsoever to do with the content of the reasons offered, but whether, if we assume them to be true, they force us to then accept the truth of the conclusion. We’re not actually concerned here with whether the premises are true, just with whether, if they were to be believed, the conclusion would have to be believed as a consequence. In this way, formal fallacies are all about how the premises connect to the conclusion, even if the premises are completely abstract (e.g. all As are Bs) or utter nonsense (e.g. all Klemps are Plerbs). These premises could be used in valid deductive arguments without any formal fallacy being committed (this is the opposite of what is true for informal fallacies). Valid deductive arguments are the only arguments that don’t contain a formal logical fallacy. We’ll learn a lot more about formal fallacies in Chapter 6 Part A and Part B.

Formal fallacies are often also called deductive fallacies because they mostly concern deductive arguments. In Chapter 6, we’ll cover the rules of deductive logic, the types of formal fallacies, why they’re fallacious, and how to spot them.

When we’re looking for formal fallacies, the content of the argument isn’t a concern. Take the following example:

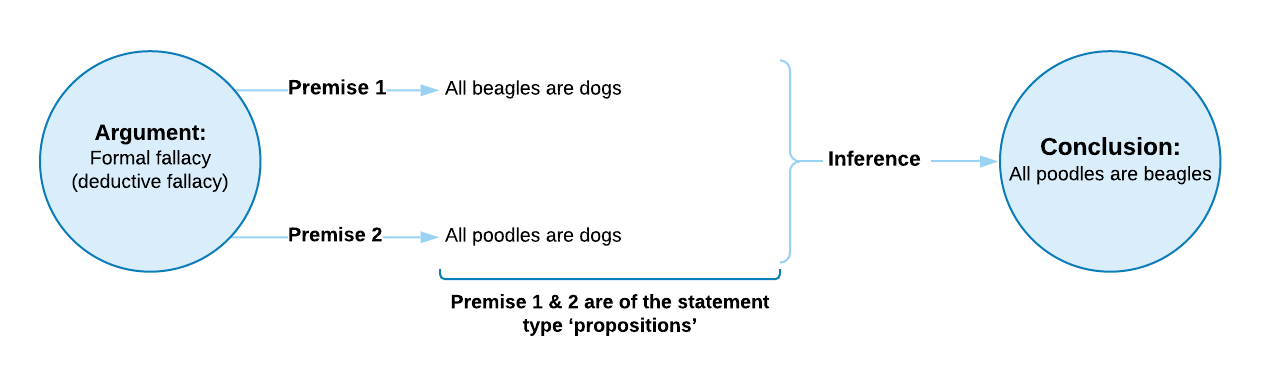

It’s easy to see here how the conclusion can’t be confirmed just by these premises. Xs are a subset of Q, and Ys are a subset of Q, but nothing in the argument tells us that these two subsets overlap, so the conclusion is unfounded, invalid, or fallacious (these can be interchangeable terms). The point is that these premises don’t really have any content – they don’t actually say anything. Xs and Ys and Q could mean anything at all. So, it isn’t what the premises say, but how they say it, and how they link to the conclusion that’s the problem here.

This is fallacious, whether we’re talking about dogs or not (it isn’t content-dependent).

The problem here is with the form, not the content, so it is a formal fallacy.

Informal fallacies can be a little more difficult to pin down. This label is sometimes used as a catch-all category for all fallacies of reasoning that are not formal. They mostly involve a ‘sin of irrelevance or ambiguity’ in the argument – appealing to facts, issues, ideas, or evidence that have nothing to do with the central argument. In this way, the informal fallacy has everything to do with the content of the premises – it’s about what they say. Informal fallacies can be thought of as distractions in the argument. Informal fallacies are much more common in everyday discussion and commonly arise from the misuse of language or evidence. An informal fallacy has been committed when a conclusion isn’t made more believable by the presented premises. I say believable because when it comes to informal fallacies, we’re usually taking about an inductive argument, so the formal fallacy ‘non-sequitur’ has already been committed). There are three common types: ambiguity (propositions that are insufficiently clear), relevance (propositions that don’t address the issue at hand), and sufficiency (propositions that are too weak to support the conclusion offered).[2]

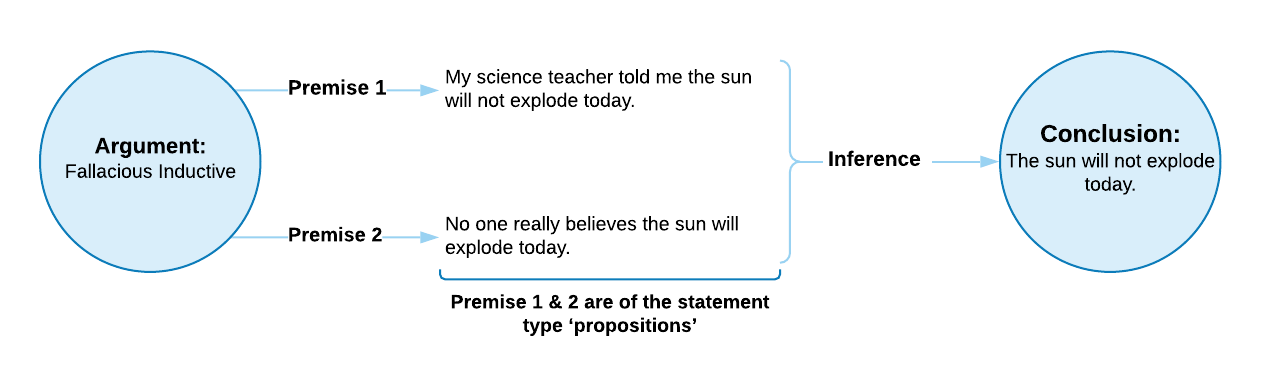

Returning to our ever-reliable sun for an example, a fallacious inductive argument could be:

The conclusion ‘The sun will not explode today’ seems equally certain as in the sun example from Chapter 2, Part A, but the premises on which it’s based are deeply flawed – meaning they give very little reason to believe this conclusion. Therefore, the inductive argument is weak because of its appeal to fallacious argumentation strategies. There’s another crucial lesson here: just because this argument is fallacious and weak, doesn’t mean the conclusion is false because the sun will certainly not explode today. Fallacious reasoning doesn’t guarantee a conclusion is false – it only guarantees a better argument is needed before the conclusion is worth believing. When you come across a fallacious argument, don’t reject the conclusion. Simply demand a strong argument with better reasons and evidence to serve as premises.

‘Informal fallacy’: In contrast to formal fallacies (which concern the inferential move and whether it’s legitimate), informal fallacies are concerned with the content of the premises and whether what they’re actually claiming is relevant, sufficient, and clear to the argument. Content here refers to what the actual premises say, and whether their claims are insufficient, irrelevant, or ambiguous. Informal fallacies make an argument unpersuasive. Informal fallacies occur when bad premises are used that simply don’t provide any good reason for believing the conclusion.

An informal fallacy occurs in an argument that offers a reason (premise) that’s insufficient, irrelevant, or ambiguous. Some students confuse this with an analysis of whether the premises are correct or true. But that’s a different matter. A true premise creates an informal fallacy if it’s too weak to prop up the conclusion, completely irrelevant to the conclusion, or ambiguous in its meaning. We’ll learn a lot more about informal fallacies in Chapter 7.[3]

Logical fallacies can be powerful rhetorical and persuasive tools that are intentionally used to market, mislead, and manipulate. Advertisers, propagandists, charlatans, and sincere though unwitting people employ fallacies in their argumentation. That is, there are people who will intentionally use fallacious argumentation because they know these types of arguments can still be very convincing psychologically. This chapter will introduce you to the forms of fallacies without going into detail on actual fallacies. Logical fallacies will be the subject of Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 (this one is getting far too long as it is).

There are many taxonomies of fallacies you can study. Whole books have been compiled to serve as reference guides. There are even cool posters you can buy. Here is a useful compilation of 231 common fallacies from the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. By studying these types of lists, you’ll get a sense of what qualifies as a fallacy, and you’ll get better at spotting them for yourself

A final note on fallacies: The burden of proof is always on the person making the claim. If you claim someone is committing a logical fallacy, the onus is on you to describe the fallacy and explain how it invalidates the reasoning. Too often in debates (especially online) people throw around accusations of fallacious reasoning without even knowing how the fallacy has been committed or what impact it has.

Decision and Values

These appraisals, despite being listed last, should always come first. Decisions about values forms part of the critical thinking process because there is a huge difference between those claims and ideas that matter, and those that simply don’t. Consequently, a major task in exercising your critical thinking is the ‘appraisal of value’. This is where the rubber meets the road, so to speak. Of course, not everything people argue over matters, yet there are many things that do deserve our attention and scrutiny. This also relates to our discussion in Chapter 1 about our moral obligation to be critical thinkers so that we can serve our own values and interests properly. We do ourselves, our values, and our communities a major disservice when we don’t properly evaluate the importance and implications of beliefs, arguments, decisions, policies, and actions.

The appraisal process centres on whether something actually matters, who cares, and being clear about why. We don’t have infinite resources to dedicate to arguing with every fanatic online or debunking every outlandish new idea. We need to make careful examination of the potential implications of certain ideas and arguments so we can devote our time and resources to those that matter to us. In order to achieve this, we need to be aware of our own values and priorities. The growing anti-vaccination or ‘anti-vax’ movement has potentially lethal consequences for the children of the world, so this might be something I’m willing to risk a thousand headaches over. In contrast, the growing pseudoscientific claims made by the anti–GMO movement might be merely a nuisance or entertaining to me (such as the hilariously labelled ‘non-GMO salt’). Whether we realise it or not, these are decisions we must make every day.

This isn’t just relevant for deciding who to argue with online, but for more everyday tasks such as deciding which products to purchase at the supermarket. For example, the growing trendiness of organic or anti-GMO products might turn out to be nothing more than a luxury First World privilege that’s harmful for the environment and provides no extra health benefits. These decisions not only inform how we engage in critical thinking activities, but also require critical thinking to know how to approach them in the first place. You might hold the opposing view on vaccines, GMO foods, homeopathy, or whatever. Still, whichever side of the debate you fall on, you need to be clear about your very compelling (non-fallacious) reasons, and have on hand, strong evidence to support your position. Alternatively, these particular issues might seem unimportant for you – this determination should also be made consciously and overtly based on your own values. You might be a politician who only values winning and not the safety of children, so taking an anti-vaccination stance to secure certain voters’ loyalty might be in keeping with your values. Whatever your decision, you must be clear about it, and be able to explain and defend it as a rational one.

Ultimately, we influence everyone we engage with in our daily lives. Our opinions matter and have wide influence. We owe it to ourselves and the people we interact with to ensure we have the most justifiable opinions available

Tying it Together

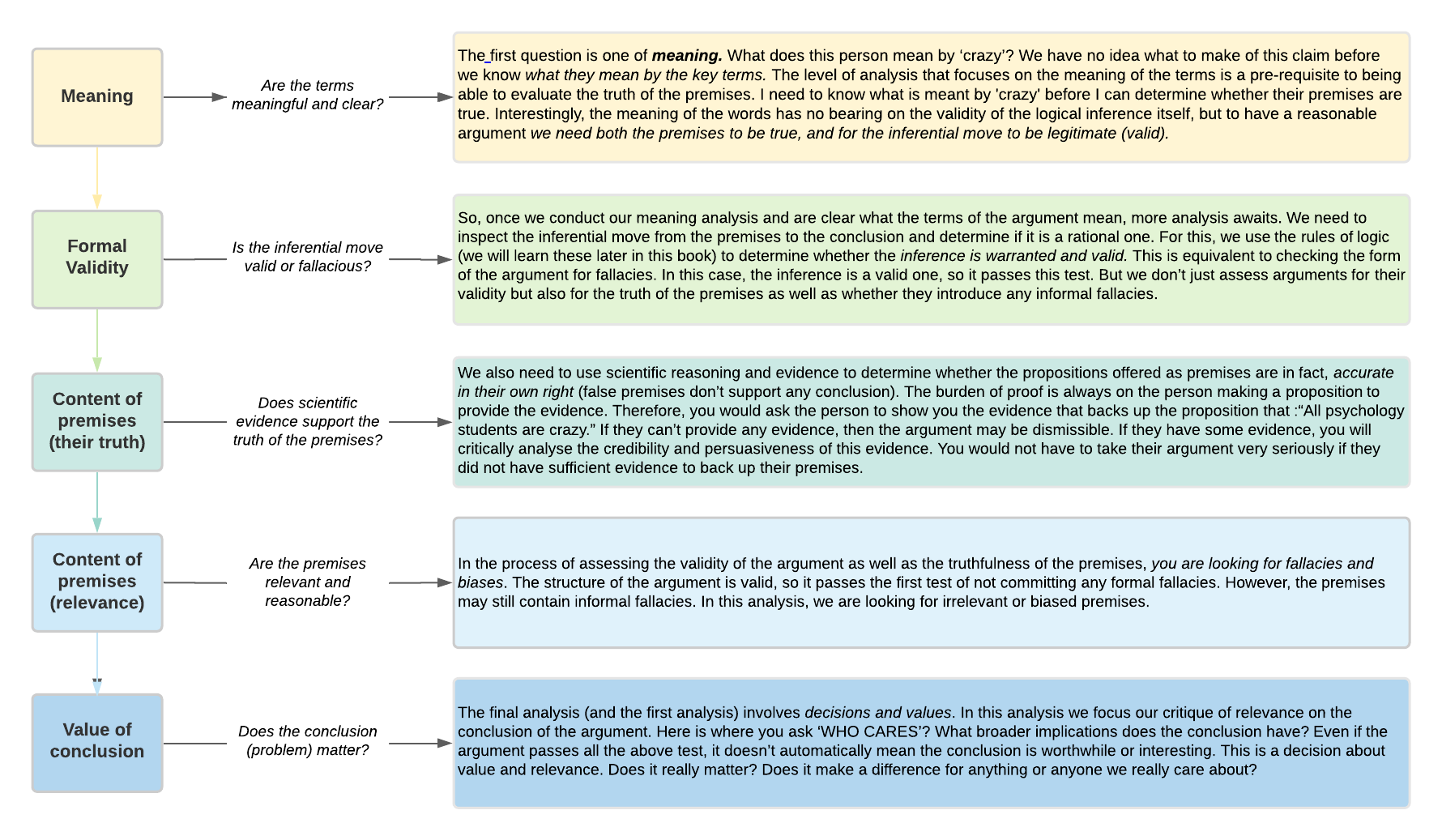

Let’s tie it all together with an example of a simple argument and how each of our appraisals bear on it. Some of these appraisals need to be done in a certain order, such as the meaning analysis – what is meant by the key terms. This has to be settled before you can get started on the rest. Other steps like the analysis of reasons, evidence, and fallacious inferences can happen simultaneously, or in different orders than I have them here. The final appraisal of relevance or importance happens throughout. You must constantly be re-evaluating whether any of this is worthwhile. Therefore, while these five tasks aren’t necessarily ordered, you can’t skip any of them!

To recap, our five main tasks (or appraisal areas) are:

- the ‘appraisal of meaning’

- the ‘appraisal of reasons’

- the ‘appraisal of evidence’

- the ‘appraisal of errors in reasoning’ (invalid inferences)

- the ‘appraisal of value’.

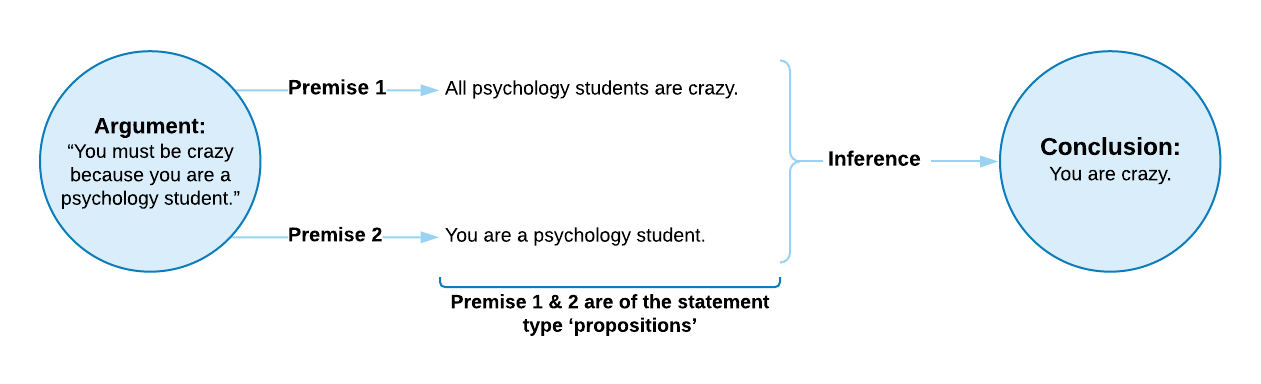

The example is: Someone says to you, ‘You must be crazy because you’re a psychology student!’. Before you decide to slap this loudmouth, you sense an opportunity to practice your newly learned critical thinking skills.

Our first task is to unpack this claim so that the premises and inferences are absolutely explicit and not buried or hidden. The full argument might be unpacked to look something like this:

2. Application: Practising Skilful Application of Critical Thinking

As you develop your understanding of critical thinking theory (don’t worry, after this whirlwind tour, you aren’t expected to have mastered anything just yet), practice is the key to cementing your knowledge and sharpening your skills. Theoretical knowledge is a necessary first step to good critical thinking, and in the above section, I outlined some of the core areas of theoretical knowledge that you’ll master studying this text, but theoretical understanding isn’t all it takes to be a successful critical thinker. Don’t forget the analogy I presented in Chapter 1 of the unfortunate UFC fighter who had merely memorised textbooks on fighting and had never actually done any actual practice. Critical thinking is equally something we ‘do’, not merely ‘know’, and if we don’t actively practice the ‘doing’, we won’t be any good at it. Each step of the process outlined above requires practice in order to master it.

Critical thinking is an applied skill, and as such, it requires you to repeatedly practice applying the concepts outlined above in order to master it. There is no shortage of opportunities to practice critical thinking. As I explained in Chapter 1, we’re constantly bombarded with information, claims, ideas, arguments, rhetoric, and so-called ‘news’. It’s unlikely you could get through a day without having an opportunity to practice critical thinking skills. Critical thinking practice requires the right kind of application of the steps, skills, and strategies outlined above. It takes conscious effort to sharpen your critical thinking by asking the right questions, looking for new information and perspectives in the right places, and weighing ideas in the right manner.

Some of us may be familiar with the 10,000-hour rule popularised by journalist Malcolm Gladwell. This rule states that to achieve expertise in something, you need approximately 10,000 hours of practice. It’s a decent-enough guide that’s helpful for appreciating the amount of work that’s required to legitimately achieve ‘expert’ status in an applied skill like playing the violin or martial arts. But more critical reflection on the evidence for this rule of thumb exposes some issues with it. It turns out the number 10,000 isn’t very well-founded, but I’d argue this misses the point. No one needs to quantify the exact amount of time needed to master a specific skill. The point remains valid that it isn’t a trivial investment. And it would be nearly impossible not to end up pretty good at something you’ve committed 10,000 hours to.

As you study critical thinking, you’ll start to notice opportunities to practice the skills you’re learning. In the absence of any checks or balances to ensure you’re genuinely practising these exercises, you could easily save yourself some time and skip doing this. But how would this benefit you? By trading in a few minutes of skilful practice time each day to play video games or watch Netflix, you’d forfeit some genuine skill development that could pay off enormously for you at some future point. In the more immediate future, these skills will help you solve problems or quizzes given to you in your classes, but in the long term, this practice could prevent you from making a fool of yourself, losing a lot of money, or could even save your life.

You can begin practising a critical approach to thinking in everyday life by looking for the claims or propositions sometimes hidden in the statements people make. A good place to start is by watching debates and speeches, and unpacking specific claims into the form of an argument (as we’ve done here before). To do this:

- First, assess whether all the terms are used in an open, fair, and consistent way.

- Then, write down the premises and conclusions of the argument in a structured way.

- Determine whether the argument is an inductive or deductive one, and then begin judging the quality of the premises in terms of how reasonable they are and whether evidence supports them – remember, the person making the proposition always carries the burden of proving their claim. Look for fallacies of reasoning, both formal and informal (if it’s an inductive argument rather than deductive, you already know there is a formal logical fallacy).

- Finally, determine how relevant and impactful the conclusion is with reference to your own values.

You can also do this the next time you find yourself in a disagreement with someone, whether in person or online. It can seem like quite a drawn-out process at first, with too many steps, but just like when you first started learning to drive, it seemed as though there were too many things to remember, after some practice, it all starts to become instantaneous and automatic.

I know by now you’re sick of hearing me harp on about practice, practice, practice. But the point I want you to take away from this part of the chapter is that, unlike much of what you learn in your university courses, critical thinking isn’t simply the development of theoretical knowledge. It’s a practical skill – something you do, not just something you know. Some university disciplines rely on mostly theoretical knowledge (like history or mathematics), and some involve physical practical skills (like medicine). Critical thinking is much more like the latter, and more practical than many people often realise. The bottom line is, if you learn all the critical thinking theory in this textbook, but don’t apply it regularly, you won’t be very good at critical thinking.

You can begin by engaging with ideas and information you’re confronted with on a daily basis. For example:

- Ask probing questions (request reasons and evidence when you’re confronted with claims).

- Expose yourself to new sources of information.

- Watch or listen to debates online or TV and practice picking out fallacious reasoning.

- Put your own ideas and beliefs up for debate with others. You don’t need to win any debates – just start practising and sharpening your own thinking. Let others interrogate your ideas and opinions and the arguments that underlie them.

This will all sharpen your critical thinking and expand your horizons a great deal.

3. Attitude: Building the Right Mindset and Disposition

Here we get to the third foundation of critical thinking: attitude. Of the three areas of development I detail in this chapter (theory, application, and attitude), this one is perhaps the most elusive to fully grasp, and maybe the hardest to develop since it requires us to cultivate our own personality in a goal-directed way. Regardless of our theoretical knowledge and our skill-development, we won’t be good critical thinkers if we don’t have the right attitude and disposition. When I talk about having the right attitude, it isn’t like a pseudo-religious set of requirements about how to be a good person. Rather, it’s just about what stance to take when you’re bombarded with claims and ideas so you’re in the best position to be critical, analytical, insightful, and have better immunity against being conned.

So, the obvious question is: ‘What is the right attitude and disposition to possess?’. What follows is a list of some of the more important attributes that are worth cultivating (again, practice is the key), and I will explain how each can support your development as a critical thinker. You’ll get the sense as you follow below that many of these traits overlap with each other, and even boost each other (I’ll discuss this at the end). This list is by no means exhaustive – there are many more that could be added to this list, but these are a great starting point against which to gauge your own development.

Scepticism

Scepticism is a disposition of suspending judgement. Suspending judgement just means you don’t make up your mind quickly, but wait until you have a decent amount of relevant evidence and reasoning on an issue. To be sceptical means to hold off on making decisions about the truth of claims until you’ve properly interrogated the reasoning and evidence using the conceptual tools discussed here. To be sceptical is not to automatically disbelieve everything, but to remain neutral about everything until you can arrive at a defensible position. This is actually harder to do than you might realise because we’re hardwired to react quickly to incoming information and situations, and to make snap decisions about what to accept as well as how to respond. All too often, we jump to conclusions with only partial information. Our beliefs and disbeliefs are often knee-jerk reactions based on faulty reasoning like gut feelings or first impressions. Being sceptical means going through the steps of critical thinking (analysis of meaning, logic and argument, scientific methods and evidence, fallacies and biases, and decision and values) before making up our mind about a claim. Being sceptical can sometimes seem like a lack of commitment, and sometimes it can be difficult to maintain a neutral stance when you’re under pressure from your social networks, or you have strong emotions about a topic. This is why it takes practice. Always remind yourself of the pay-off or – better yet – the costs of being too gullible and jumping to conclusions. Be prepared to suffer the pain of sitting on the fence until you’re satisfied there is sufficient reason and evidence for you to take a position.

Scepticism is especially necessary for ideas and information that are immediately appealing to you. Many ideas don’t get treated with enough scepticism, and are somehow smuggled through your critical thinking filter because they’re consistent with other beliefs you have, like your political, ideological, or religious worldview. We need to be most sceptical about ideas we want to be true. It’s no accident that our interpretations are invariably consistent with our existing beliefs. We’re almost incapable of making an interpretation of an ambiguous event that contradicts our worldview. This is because any concept, event, or interaction can be interpreted in an infinite number of ways. Therefore, there is always room for us to fabricate our interpretations to fit our existing belief systems. Be aware of this tendency and weed out any beliefs you have that you haven’t fully interrogated.

Inquisitiveness

The fact that you’re studying at university and have enrolled in a critical thinking course is probably testament that you’re already an inquisitive person – that you’re interested in thinking, you care about getting things right, and you know the value of investigating ideas, reasons, and evidence. Nevertheless, there is always room for improvement on these traits. Being inquisitive means not taking anything at face value and being interested in exploring the details, teasing out the nitty-gritty of an idea or argument, and wanting to probe and interrogate its characteristics. This can sometimes be a laborious task, and it’s true we don’t have enough time on any given day to properly interrogate all the claims we’re exposed to, but we need to get in the habit of asking probing questions as our first reaction to new claims and ideas. In the first chapter, I discussed the importance of questioning to your studies, as well as your development as a critical thinker. Questioning is the royal road to understanding the claims you’re confronted with, so cultivate curiosity and questioning as a habit (if people around you start to find you a little annoying, it might mean you’re getting good at it). However, one important qualification worth clarifying is that not just any question will do. Using the appraisal tools discussed so far as a guide will give you a powerful repertoire of questions with which to interrogate information. However, the important point I want to drive home here is that this willingness and desire to question is a trait or disposition that we can all cultivate in ourselves. Be curious about the reasons and evidence. Ask ‘Why?’, ‘How?’, ‘Who says?’ and ‘On what grounds?’ often, and it will soon become second nature to you. This inquisitiveness and hunger to probe deeper will serve you generally in your life endeavours.

Open-Mindedness and Even-Handedness/Balance

We all know open-mindedness is a virtue, but it’s harder to practice than preach. We cling to our cherished beliefs, instinctively dismissing anything that challenges them. Instead of fairly evaluating all sides, we often filter information through the lens of our existing views. But true open-mindedness requires more than just acknowledging opposing viewpoints; it demands engaging with them head-on. Even ideas we find abhorrent deserve to be confronted and defeated with superior arguments.

The modern trend of deplatforming—silencing those we disagree with—is a misguided approach. It’s akin to waving a white flag, admitting an inability to counter their ideas. Moreover, it stifles productive dialogue and forces dangerous ideas underground. Bad ideas are best defeated by better ones, not by censorship. In free societies, everyone has the right to express their opinions. But this right comes with a responsibility: to engage with reasoned challenges to those opinions. We all make mistakes and are susceptible to flawed thinking. Open-mindedness and a willingness to consider counterarguments are our best defence against these pitfalls.

Strong critical thinkers recognise censorship as a regressive and dangerous tool. Throughout history, the powerful have sought to suppress dissent, a practice that continues today, albeit more subtly. Modern methods may be disguised in moral righteousness, but they share the same goal as their historical counterparts: to control the narrative and maintain power. Consider the removal of individuals from social media for spreading “misinformation.” This mirrors the condemnation of Galileo for his revolutionary ideas. Both actions stem from the desire to suppress challenges to the established order.

Today, this power isn’t just wielded by governments. Media outlets and corporations also shape the information we receive, often subtly influencing the public discourse. An old adage reminds us: “You can always work out who’s really in power by asking yourself who or what can’t be criticised. Remember, those in power often seek to limit free expression under the guise of moral imperative. History shows that those who favour censorship often end up on the wrong side of history. Open-mindedness and a willingness to engage with opposing viewpoints are essential for a healthy and progressive society.

In this context, if you’re fixed and rigid in your beliefs, you have the wrong mindset to be a good critical thinker. The ongoing fight is to acknowledge and work to reduce personal biases by promoting fairness in our own thinking and openness in the information we share and consume. Consider every belief you hold – or are confronted with – as tentative and open to revision (we’ll learn more about this in the next chapter). Actively look for disconfirming evidence (without this, looking for confirming evidence is mostly a waste of time) and seek out counterarguments.

To gauge how open and even-handed your thinking might be, consider these self-check questions:

- Do all your beliefs align with a specific group or ideological worldview (e.g., political party, activist group)?

- Do the people you regularly interact with (especially on social media) share the same beliefs as you?

- How many people or pages do you follow that hold different opinions or viewpoints from yours?

If you answered “yes” to the first two questions and “a lot” to the third, you may need to do some more work interrogating your ideas, your influences, and your open-mindedness.

Introspective-ness/Insightful-ness

The Ancient Greek aphorism ‘Know thyself’ is a famous maxim (or wise saying) that was inscribed at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi (the saying is also attributed to Socrates). This should be a guiding philosophy for you in deepening your critical thinking. As I said in Chapter 1, the beginning of critical thinking is ‘Thinking about thinking’. This means we need to be interested and observant of our own thinking processes and habits, which, as I also pointed out, are not so crash-hot until we train them. If you’re not aware of how you think, it will be very difficult to notice areas of weakness and make improvements. This is another positive habit you can cultivate through practice. Watch how you think, watch how you react to new ideas and information, and notice whether there are any differences in how you react when the information either confirms or falsifies what you already believe. Watch your emotional reactions to ideas and claims – we often reason emotionally without even being aware we’re doing it (certain ideas just feel good because they confirm our pre-existing view of the world). Watch your inclination to want certain things to be true or false. Watch whether you’re open to being wrong, open to scrutinising information from all sources equally, whether you pay as much attention to confirming as falsifying sources. Ask yourself whether you’ve looked at the data to support your beliefs and actually tried to falsify them. Look at your own beliefs and begin practising the type of critical interrogation of them we described above. No belief or claim is automatically self-evident. Everything needs reasoning and evidence to support it. If you’re not aware of the reasoning and evidence supporting your beliefs, you haven’t been critical enough. Watch for beliefs you have that you think are just ‘obviously true’ and don’t really need to be given much evidential support. Understanding the basis for your own beliefs makes you more prepared to defend them if they come under scrutiny (because you’ve already applied the critical thinking blowtorch to them yourself) and puts you in a better position to scrutinise the claims of others.

Traits that Interact and Support Each Other

Cultivating these traits isn’t so much about making radical changes to your personality, but more about forming good habits. These attitudes are much more like good routines or approaches you can get into the habit of adopting on a regular basis. Just start looking closely at yourself and see what you do when you come across a piece of information or an idea. How can you improve your habitual reactions? We often have routine ways of responding that aren’t always sceptical, inquisitive, open-minded, and balanced. Cultivating the right attitude to be a skilful critical thinker is all about becoming aware of these habits and working to create new, more successful habits.

These dispositions go hand in hand to support each other. For example, the more you adopt a sceptical stance, the more inquisitive you’re likely to be – you’ll be on the lookout for reasons and evidence to support or refute ideas you’re confronted with. The more you introspect on your own thinking, the more you’ll develop greater insight. One result of this will be greater open-mindedness and fairness as you become more aware of – and confront – your own biases.

Additional Resources

By scanning the QR code or going to this YouTube channel, you can access a playlist of videos on critical thinking. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

By scanning the QR code or going to this YouTube channel, you can access a playlist of videos on critical thinking. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

You can access posters and flashcards mentioned in or related to this chapter using the links below:

The Logical Fallacy – Thirty of the most common errors in argumentation.

Free Creative Commons think-y things (posters and flashcards available as PDF downloads)

- See: Petrisor, B. A., & Bhandari, M. (2007). The hierarchy of evidence: Levels and grades of recommendation. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics, 41(1), 11-15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2981887/ National Health and Medical Research Council (2008). NHMRC additional levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines. https://www.mja.com.au/sites/default/files/NHMRC.levels.of.evidence.2008-09.pdf ↵

- In Chapter 7, we’ll learn about the full meaning of these three groupings and the names of many informal fallacies that they represent. ↵

- Tips for determining if a fallacy is formal or informal: Remember formal fallacies are just a matter of determining if, when accepting the premises as true, we’re forced to then accept the conclusion as true (regardless of whether we actually think the premises are true or not). In this way, formal fallacies are all about the inference. Informal fallacies are more about weeding out premises that are insufficient, irrelevant, or ambiguous with regard to their role in the argument. Any premise that is insufficient to make the conclusion more believable, irrelevant to the conclusion, or ambiguous as to what it’s actually claiming is informally fallacious. ↵