Chapter 1. What is Critical Thinking?

Learning Objectives

- Understand the power of questioning

- Understand what it means to be critical

- Understand the ways critical thinking is different from our mundane everyday thinking

- Appreciate the fundamental vulnerabilities of our everyday (untrained) thinking

- Recognise our broad (moral and social) obligation to be critical thinkers

- Recognise the central role of critical thinking to social and occupational success

- Understand the two steps to broad improving critical thinking: (1) examination and understanding, and (2) practice and application.

New Concepts to Master

- Socratic questioning

- Critical thinking versus everyday thinking

- Creative thinking

- Thinking as mental behaviour

- Living examined lives

- Concepts as tools/lenses.

- Post-truth era

- Fourth industrial revolution

- Attention economy

Chapter 1 Orientation

Let’s sketch out a road map for this chapter’s journey. In this first chapter, I have tried to focus on anticipating – and answering – questions that a curious (maybe even cynical) student might have as they begin this text. Some of these questions might seem very elementary, but progressing through these from the beginning will make sure we are all starting out on the same page. This might all feel like ‘cheerleading’ on my part on behalf of critical thinking, and that’s simply because it is. If I can convince you to take this content seriously and learn as much from it as you possibly can, you’ll benefit greatly.

Our first question will try and pin down what it is we’re looking at in this book.

Question 1: What is critical thinking?

Our second major question will address the issue of motivation and ask why we should even bother with learning and developing critical thinking.

Question 2: Why learn and practice critical thinking?

Our next question focuses on the broader context and the relevance of critical thinking in modern life, as well as the ever-changing workforce.

Question 3: Who should study critical thinking?

Our final question gets down to the practicalities.

Question 4: How do we improve our critical thinking?

This chapter’s content will also contain two side-tours into related topics. We will look at questions themselves and how they can be used to accelerate your learning and develop critical thinking skills. We will also look at the connection between creativity and critical thinking.

The Art and Power of Questioning

We will begin with one of our two side-tours for this chapter: the art and power of questioning. There are many reasons to focus on questions, but for your most immediate purposes, they’re going to be a huge ally for you during your university studies. For your success at university, questioning is both essential and constructive, and in fact, you might not accumulate much more after your first weeks of study than a long laundry list of questions. This is what we’d expect, so don’t stress about it. Answers will come in time, though you should ensure you’re tenacious in hunting them down, which is half the fun. If you find you’re only accumulating more and more questions during this early period of your university study, it means you’re probably doing something right: paying attention. Keep in mind, you’ll need to ensure you’re constantly reaching out to your peers, your lecturers and student support staff to get answers. Questions are powerful tools, but like any tool, they won’t help if you don’t put them to proper use. Questions are simply a means to an end – don’t hold on to them or get bogged down by them.

Another reason to spend some time thinking about questioning is that this simple everyday activity is central to critical thinking. In addition to critical thinking, all tertiary education should be a training ground for teaching you how to think, and questioning is a central and invaluable part of both learning and doing ‘thinking.’ Not only critical thinking, but any development of knowledge – such as scientific research – begins with a question. It’s how all of us learn. Failure to question is like having the brakes on the development of knowledge and understanding. Historically, this actually happened for hundreds of years when people through the Middle Ages failed to question the truths of the church and the teachings of Aristotle. Aristotle was an influential ancient Greek philosopher who founded science and invented logic, yet he was wrong about tons of stuff – he thought women had fewer teeth than men, he thought eels didn’t reproduce, etc. Yet, for thousands of years no one questioned Aristotle’s claim that of two objects the same size – like identically shaped bowling balls – a much heavier object would fall faster than a lighter object until Galileo disproved it almost 2000 years later.

There is a famous quote that goes ‘Prudens quaestio dimidium scientiae’, which means ‘to know what to ask is to already know half’ (I have tried to find the source of the quote and the best sources point to medieval philosopher Roger Bacon). Regardless, developing your skills at asking questions is half the journey to gaining knowledge and becoming a powerful thinker. German philosopher Immanuel Kant put this point as eloquently as ever (sagacity and insight means exceptionally smart stuff):

So the best advice I can give you at this early stage of your training in ‘thinking’ is to generate and ask plenty of questions, listen carefully to the questions posed by others, probe the answers you receive and use them to stimulate more questions. Normally, questions are something that just pop into our heads in an unconscious or automatic way. However, I’d like you to try a different approach and be active and creative in generating penetrating questions as a way to actually learn and discover more. Use questioning as a way to engage more with this book’s content, with your lecturers and with your peers. This will achieve several things: firstly, it will improve your own thinking, secondly, it will help you remember content better, and lastly, it will help you build relationships with other students and teaching staff. Questioning also boosts the thinking of others hearing or responding to your questions because questioning stimulates new ideas and nurtures creativity, which is another key concept you’ll be introduced to in this chapter.

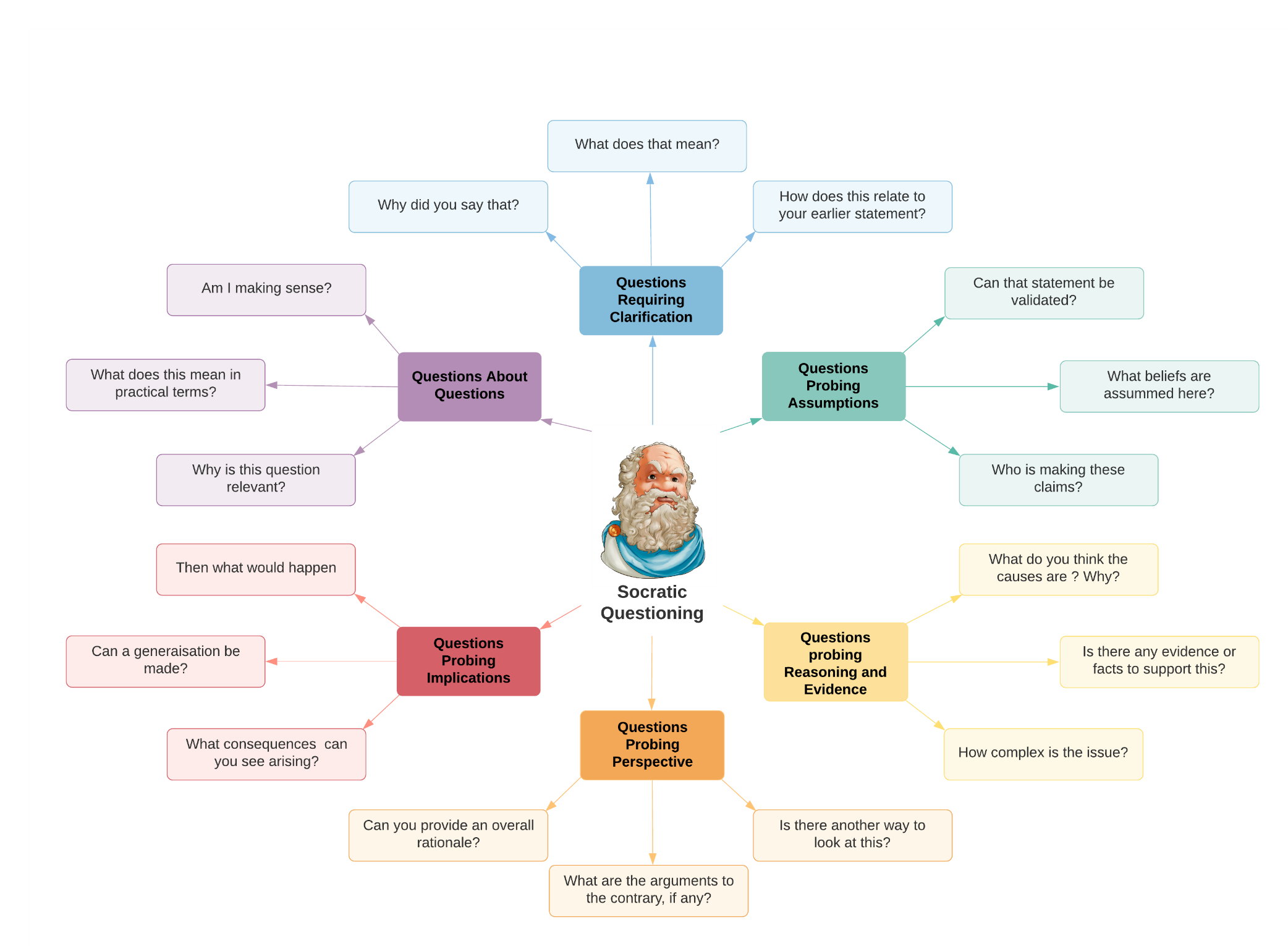

This questioning approach to learning is what is called the ‘Socratic method’. Socrates is one of the greatest and most influential thinkers of all time, though he never actually taught anything or presented his own ideas directly. Instead, he saw himself as something like a midwife delivering knowledge as a baby. He would insistently draw information out of his students by repeatedly asking questions that forced them to clarify and deepen their own thinking. Socrates might be called the first great critical thinker. We will hear more about him later in the book.

Hopefully, this chapter’s content will help you clarify some of the questions you may have as you embark on studying this text, and if we are lucky, it may even answer some of them. But there is a broader purpose to structuring this chapter’s content around questioning. I hope to show you how systematic questions can guide and structure our thinking. In fact, this whole text is intended to help you learn how to ask the right kinds of questions and also how to interrogate the answers you receive, which is a skill that will serve you for the rest of your university studies – not to mention your life and career. Like most of the tools mentioned in this book, questioning can be learned and improved through practice. Perfecting this skill isn’t just worthwhile for you during your time as a student. The professional world is also becoming more and more aware of the power of questioning, so mastering this skill will empower you for greater success later in your career. Therefore, ask questions as though you’re practising the art of questioning itself and as you get better at questioning, you’re improving your critical thinking.

A final note on questions: some people have important questions that they never get around to asking because they’re uncertain if the questions are silly – and therefore, unimportant – but these are two very different things. I have never been the type of lecturer who likes to claim ‘There are no silly questions’ because, of course, there are plenty, and I have been responsible for asking many myself over the years. What is true, though, is that ‘There are no unimportant questions’. Even seemingly silly questions serve an important purpose because they can help clarify information, pinpoint where you might have gone off-track, and even aid other students who may not have realised there was a gap in their understanding. Any time you need clarification on a concept in this text (or any course content), you should reach out. Questions stimulate conversations, which help us think and learn. In other words, questioning is critical thinking.

What is critical thinking?

Let’s get onto the first major question for this chapter. Since the text is called ‘critical thinking’, clarifying what this is seems like an ideal place for us to start. Since the foundation of critical thinking is self-reflection and self-examination, start by reflecting on ‘What comes to mind when you hear the phrase “critical thinking”?’ Consider your own ideas about this first, and once we go over some of the more conventional conceptions, you can reflect on how your pre-existing understanding might compare with what we are learning in this chapter.

As you might guess, critical thinking means many different things in many different contexts, and to many different people. It’s actually impossible to find a definition that everyone agrees on. In fact, critical thinking has become something of a popular buzzword in education, science and academia. When concepts achieve a type of ‘trendy’ status, they sometimes lose their meaning and become impossible to get a handle on. Don’t worry, we are going to unpack it in this chapter.

It’s important for us to set out on this journey with a firm conceptual grounding on what exactly we are talking about when we use the phrase ‘critical thinking’. We can start our attempt to understand what this is by breaking it apart into its constituent words. So let’s look at the two words ‘thinking’ and ‘critical’ separately.

‘Thinking’

Let’s start with clarifying the notion of thinking. What is thinking? Thinking is an activity we are so intimately connected with that we risk having an unearned sense of certainty about our ability to define it. That is, until the point where we actually have to do so. This exact crisis of confidence hit me about five minutes before attempting to write this part of the chapter. It can be a bit like asking a fish to explain to you what water is. Nevertheless, to master critical thinking, it’s essential that we understand the thinking process itself.

Defining this ‘thinking’ that we all do constantly in specific terms has actually been quite a difficult problem throughout human history. Philosophers and psychologists have spent hundreds and even thousands of years pondering the nature and activities of thinking, and some very impressive and technical work has been done in this area, though we don’t have to delve so deep in our very first chapter.

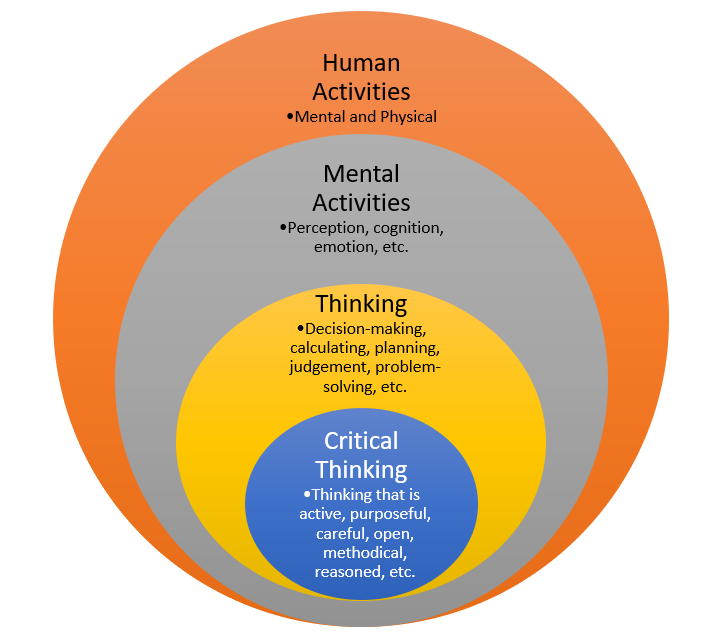

Let’s start at the most obvious and basic points. Thinking is a mental activity that we can easily contrast with physical activities like walking. To state the obvious, a mental activity is an activity that happens inside our mind, and therefore, it’s private and internal (that is, until Elon Musk perfects his mind-reading device).[1] As an activity, it’s ‘active’, which just means it’s something that we actually do rather than something that happens to us – though it can sometimes feel like we do it unintentionally or unconsciously. Thinking is also one among many different types of mental activities or states. Others include perception, memory, emotions and daydreaming. Those of you who are studying psychology will learn a great deal about all of these throughout your degree, however, in this text, we will focus on thinking specifically. Many mental activities come under the umbrella term ‘cognition’, which you’ll come across many times in your study. The terms ‘cognition’ and ‘thinking’ are sometimes used interchangeably, but it’s clearer to use cognition as a broader term to encompass many related mental processes – those like perception, thinking, learning, language, and memory.

Tackling tricky definitions is often helped by compiling a list of things that we agree belong under a term (i.e. the instances of the thing we are trying to define) as well as things that don’t. By sorting cases like this, we can abstractly identify what they have in common. We’ve already started to do this above by identifying some mental activities that we wouldn’t consider thinking. In contrast to these non-thinking activities like perception, emotion and memory, mental activities that most people consider ‘thinking’ include decision-making, calculating, planning, active comprehension of complex material, judgement and problem-solving. We can work out what might be common among these examples and tentatively conclude that thinking involves some type of mental manipulation or processing of information, symbols and/or ideas. This idea of processing or manipulation is just another way of saying we are actually ‘doing’ something to, or with, the information and ideas.

As I said before, thinking might not always be intentional or conscious, but we can see from the above list of activities that it can be quite active, strategic and skilful (or not, depending on your training). Since it isn’t just any type of thinking that interests us in this text, but critical thinking, we should get clearer on what this critical type of thinking refers to.

‘Critical’

In everyday conversation, the word critical is used in many different ways. In one sense, to be critical means to criticise. People often confuse being critical with being judgmental or even disapproving, such as pointing out the flaws in someone or something. Critical thinking isn’t all about criticising, which can be more like a negative, thoughtless knee-jerk reaction to things we don’t like – the opposite of critical thinking.

A more general and appropriate use of the term would be to represent an analytical and interpretative activity, such as how a thoughtful and attentive art critic views a painting. Good art critics don’t reactively jump to conclusions or naively pour scorn on artworks. They carefully and methodically consider the piece of art and make a thoughtful and reasoned evaluation of it. In this sense, being critical has nothing to do with being unnecessarily negative, but rather is a skilful way of viewing things methodically in a careful and evaluative way. Therefore, being critical is a good thing. To do this requires the use of a range of mental tools that we will discuss as we progress throughout the text. When it comes to thinking, being critical means to be analytical and reflective of the thinking process itself as well as our ideas and beliefs, and doing this in a purposeful and systematic way. In fact, we can be critical about almost anything, and we can apply critical thinking skills and tools to just about any topic or area of our life.

This description suggests that being critical isn’t something that’s likely to be innate – meaning we aren’t automatically born with it. Rather, it’s something that’s acquired and then developed, often over many years. Only skilled analysis and examinations will actually produce useful evaluations and interpretations, and only training and practice can ensure our analysis and examination are done skilfully rather than error-prone or haphazardly. To be successful in your critical approach means you need to be careful and deliberate, and this requires training. A second aspect that should become apparent at this point is that critical thinking isn’t the kind of thinking we do when we aren’t trying. Not only is being critical learned rather than inborn, but it’s also not our default mode of thinking until we make a habit of it.

Critical thinking

Now we have a handle on what thinking is, and we know a bit about what critical means, we can determine several things.

Firstly, thinking is a distinct kind of internal mental activity.

Secondly, being critical is a special skilful mode of thinking (since not all thinking is critical). It has specific attributes such as being active, purposeful, careful, evaluative, open, methodical, reasoned, etc. We’ll go over these attributes and others as we progress through this text.

Thirdly, critical thinking skills are learnable, perfectible and must be deliberately cultivated and performed (i.e. they’re neither inborn nor automatic).

For comparison, non-critical thinking would include the kind of thinking we do when we’re on autopilot and our mind is flitting from one thought to another without any real goal, and without us being very aware or deliberate about it.

The following nested Venn diagram is a useful way to think about what we’ve covered so far. It shows how we’ve located critical thinking as a specific subtype of thinking, which is a specific subtype of mental activity, which is a specific subtype of human behaviour. In this way, you can situate the focus of this information in your broader understanding of these topics. This will be especially useful for helping students studying psychology degrees to locate the focus of the current content in relation to their other courses, which will focus on other aspects of this diagram.

Some Established Definitions (for Completeness)

These descriptions will start to feel quite familiar at this point.

One of the most influential accounts of critical thinking describes it as active and skilful and involves interpretation and evaluation activities applied to information, observation, and communication (Fisher & Scriven, 1997, p21). This definition is useful in identifying some of the targets to which critical thinking can be applied. These are:

- observations

- communications

- information

- arguments.

In navigating our daily lives, being critical of the information and observations we make is indispensable to our success.

From a cognitive psychology perspective, Halpern (2003, p. 6) explains that critical thinking is the application of a set of cognitive skills or strategies directed towards achieving an outcome. On this account, critical thinking is a reasoned activity employed purposefully with some objective in mind. This definition highlights another aspect of critical thinking that I haven’t mentioned yet: that it’s goal-directed and goal-oriented. This means critical thinking is engaged to produce a certain outcome, whether that be an interpretation, a decision, an action, or a solution to a problem. We need to engage our critical thinking to determine how to properly understand what’s going on, whether we can believe what we’re being told, how to act and how to achieve our goals.

Though it may seem straightforward, defining critical thinking has been the subject of quite a bit of debate. A research study was even conducted with ‘experts’ to try and reach a consensus as to what critical thinking is all about. You can read about their results and decisions in The Delphi Report.[2]

Critical ‘versus/and’ Creative Thinking

This section will cover our second side-tour of this chapter: Creativity versus critical thinking. Since these two concepts are rarely spoken about in the same breath, you’d be forgiven for wondering: ‘What has creativity got to do with critical thinking?’. But I hope to show you how the two are, in fact, very closely linked, and even interdependent. Earlier in this chapter, I’ve started to answer the question ‘What is critical thinking?’, so hopefully you’re up to speed on that.

Since this is meant to be an intellectual discussion, let’s begin by outlining some definitions of creativity. One popular definition by Robert E. Franken (1994, p. 396) highlights two important things. Firstly, it emphasises that the acts of ‘creation’ and ‘recognition’ of (1) ideas, (2) alternatives and (3) possibilities are creative acts. Therefore, recognition of novelty (or new things) is creative, just as generating novelty is. It also identifies some of the areas where creativity is most useful: problem-solving, communication, and entertainment. We’re quite familiar with the role of creativity in producing entertainment products (such as in music, film, art, and dance etc.) but we may be less aware of how instrumental creativity is in our simple daily activities of communication and problem-solving.

Another good definition that ties in well with critical thinking activities is provided from Ghuman and Aswathappa (2010, p. 540). They explain that, in addition to generating new ideas, creativity involves challenging assumptions and viewing things from alternate perspectives. Here we are getting even closer to key tasks involved in critical thinking. Yet again, many people may not recognise the essential need for creativity in the act of challenging assumptions or beliefs, seeing things from a range of different viewpoints, and developing new ideas. It may not be obvious that these are actually creative acts.

The first thing that’s apparent from these definitions is that creativity is much more than painting a picture or writing a song. It’s, in fact, a fairly commonplace day-to-day type of activity. It isn’t some magical or mystical power that only a few geniuses possess. We all have it to some extent, and the extent to which we have it depends on some inborn inclination (including being interested in creative pursuits) but is also determined by our interests, experience, and training. All individuals possess creativity, or we would be essentially immobilised in our life – we never would have overcome the first hurdle that we came to.

The common misconception that critical and creative thinking are unrelated or even incompatible types of thinking is based on dodgy old-fashioned stereotypes. You may have heard the very common ‘right brain versus left brain’ myth, which claims the two sides of the brain favour different functions, with the left being for analytical, rational, and logical functions and the right being for creativity. Some people even believe that some individuals are exclusively ‘left-brained’ or ‘right-brained’ in their tendency to be analytical and creative. Well, these claims are simply not true at all. Both of these myths have been debunked. Both hemispheres of the brain work in concert to produce critical and creative thinking, and we are all both left-brained and right-brained people.

As we’ve seen from the previous definitions, creativity is actually indispensable to many steps in critical thinking. The ability to think imaginatively about a situation and problem, and to come up with new ideas, perspectives, and insights is essential to critical thinking. Creativity gives us the ability to see a situation and a problem in a new light and generate new solutions – or view and use old solutions in a new way. Good critical thinking depends on mental flexibility and innovation, which are features of creativity. We saw previously that critical thinking is a goal-directed activity, which means that it’s used to achieve something specific. Whether the goal is to produce an interpretation, an evaluation, a decision, an explanation, an action, or solving a problem, your degree of success will be determined by how creative you can be at generating a range of options to consider.

Imagine you’re a songwriter in a band, and you’re putting together some guitar riffs. As you go about choosing notes and arranging them and perfecting the tempo, the rhythm, and the structure of the piece of music, you need to be constantly appraising the work. You must review each step and critically evaluate it and how it serves the piece of music. This process of analysis, reasoning, and problem-solving as you’re being creative is nothing other than active critical thinking.

Now imagine you’re an investigative journalist looking into political corruption. As you gather information and evaluate its credibly and usefulness, you’ll need to be able to generate a range of alternative explanations for events. You’ll need to use imagination to view the information and people from a range of different perspectives. You’ll need to be innovative in your approaches to investigation to circumvent the obstacles put in your path. You’ll need to see how the pieces fit together, find hidden patterns, make novel connections between things, and experiment with new ideas and hypotheses about what’s going on.

In this way, a critical thinking activity relies heavily on creativity to be successful. They’re highly interdependent and very similar skill sets. Creativity enhances critical thinking, and critical thinking enhances creativity. Both skill sets share another similar feature in that they can both be learned and developed. All it takes is self-reflection (watching how you think and how you create is the starting point) and some practice. So, learn these skills and then get practising. Just like a weightlifter building muscles, repetition and dedication are the keys.

Before we leave off on this side-tour, I thought it only fair that I give you some preliminary practical strategies to improve your creativity. Things you can start doing right now to be a more creative person, and by extension, a better critical thinker. The first thing you need to begin is to understand that creativity is a skill that you need to practice (I know I’m repeating myself but squashing this myth is the first step to being more creative). Like other complex skills, and like critical thinking, you can’t get more skilful at it if you don’t dedicate yourself to practice.

Strategies to Improve Creative Thinking

In order to improve your creative thinking, you need to start with increased awareness and exposure. Start to pay attention to how you think, how you create, how you tackle problems, how you generate ideas, and how you expose yourself to ideas. An uncreative monotone environment is just not conducive to creativity. Do you live in an echo chamber of ideas and input? Notice how many new ideas you expose yourself to. Whether that be in the form of different news channels, TV shows, books, podcasts, social media content pages (these are actually orchestrated to only provide you with input you have engaged with before or input that confirms what you already believe). Creativity feeds off new and challenging ideas, new and challenging viewpoints, and new and challenging perspectives. If you live your life only digesting and parroting the opinions of your favourite ‘thought leaders’, you’re not an independent thinker. In fact, your voice and thinking has merely been co-opted and ventriloquised by other people or agendas. Check whether your opinions align in every way with any major political or ideological position. If so, there’s a chance you’ve been ideologically captivated. For example, if knowing one of your opinions (for example, on gun control) allows me to easily predict all your other positions on important topics (for example, abortion or immigration), you may not be as independent a thinker as you might believe.

The solution is to try to expose yourself to input you aren’t used to or even disagree with. Genuinely try to put yourself in the shoes and inhabit the worlds of new and different people. People you don’t like or disagree with – even including fictional characters. As you go about this, notice the limits you put on yourself and your influences. Read, listen, watch, and converse widely with others outside the genres you’re used to and expose yourself to as many different viewpoints as possible. Challenge yourself to regularly do something different that you haven’t done before. It doesn’t have to be skydiving – it might just be to drive down a road you haven’t been down before or cook a dish you haven’t tried before.

After practising some introspection and raising your awareness, as well as scrutinising your ‘environment of ideas’, it’s time to take the plunge and start practising the art of creation. In this step, you simply rehearse generating new ideas, perspectives, and solutions. This practice is intended to be playful, so don’t be too serious about it. You can apply this to anything:

- How many uses of a kitchen item can you think of?

- How many activities can you list to do if time and money were not an issue?

- How many solutions can you come up with for a fictitious problem – the crazier, the better!

This is the classic blackboard method for releasing our creativity from the confines of everyday conventional thinking. The point here is just to practice loosening up our thinking and learn about ourselves as we go about doing this. The aim of this exercise is to produce long lists, not good lists – or diverse quantity over quality. During this practice, notice the automatic tendency to immediately evaluate and even belittle certain ideas. You may notice yourself reflecting on items in the list saying, ‘That’s dumb!’, ‘That’s impractical!’, ‘That won’t work!’, ‘That’s too much like the other options!’, etc. A key part of this exercise is to pick up on this internal monologue. It’s natural and everyone does it, and it’s part of how we evolved to survive by making instantaneous evaluative decisions. We all have an internal ‘voice of criticism’ that likes to provide negative running commentary, ruining our creative pursuits. Part of this exercise is intended to minimise the influence of this voice of criticism during the creation stage. Recognising and relaxing this knee-jerk, reactive ‘criticism’ is an essential step in becoming more creative. At this point, suspend all judgement and be crazy and outlandish in your ideas. Evaluation of ideas can come later, but there’s no place for condemnation when we’re simply generating ideas. Evaluation throttles creativity. Here is where repetition is so important. The more practice you get in generating options, ideas, pathways, uses, activities, solutions, etc. the better you’ll be at it.

Because of the overlap between critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving, we’ll cover additional strategies in later chapters that deal with these neighbouring topics.

Why Learn and Practice Critical Thinking?

We’ve spent some time previously discussing what critical thinking is, so now it’s time to address the why question. One of the most common questions students have at the beginning of any course is ‘Why is this information necessary or important?’. Most students rightfully want to know why they’re investing their time in this stuff, and what is to be gained by studying thinking. Luckily for me, there are excellent answers when it comes to learning critical thinking, and I think by now, you’ll be able to anticipate many of them yourself.

Before we launch into my reasons, we should absorb some wise words from theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, who acknowledges that we mustn’t fool ourselves, as we are the easiest to fool.

To me, this quote[3] sums up the overall spirit motivating us to engage with critical thinking. The only thing I’d add to this is that while we’re very adept at fooling ourselves, we can also never underestimate how susceptible we are to being fooled by other people – especially those who know how to think and communicate in more clever and sneaky ways than ourselves. We have a swarm of in-built vulnerabilities in our perception, thinking, and decision-making that we’ll cover in detail later in the text, and these are well-known to hustlers and charlatans of all types. Becoming an expert critical thinker is the best way to arm yourself against those who seek to exploit our in-built vulnerabilities to lie to, cheat, and steal from us. As Feynman aptly puts it, one of the people looking to do this is our very own sly selves. We’ve all suffered that horrible feeling of annoyance at ourselves after talking ourselves into doing, believing, or buying something against our better judgement.

Now on to the detailed reasons. I previously gave three primary reasons to study and improve your critical thinking skills:

- Firstly, thinking affects every aspect of our lives. We can’t avoid doing it, so we may as well do it well.

- Secondly, we’re not innately or automatically good at thinking. This comes as a surprise to most of us.

- And third, we have something of a social and moral obligation to be good at critical thinking. It isn’t all about us!

Let’s go over each of these in turn.

Thinking Infects Every Aspect of our Life

We’re almost always thinking in some way. In fact, one of the hardest things to do is to stop thinking for any extended period of time. We spend almost 24 hours of the day engaged in some form of thinking. When sleeping, we think; having a shower, we think; when we’re eating, we think – hopefully you’re thinking while studying these chapters! From birth to death, thinking is the foundation of almost everything we do, and the degree of success we have in life is influenced a great deal by how good we are at thinking.

So, the first answer to the question of ‘Why study critical thinking?’ is simply because thinking infects everything we do, and every aspect of our lives. Aside from breathing, perhaps, what else could be more important to be good at?

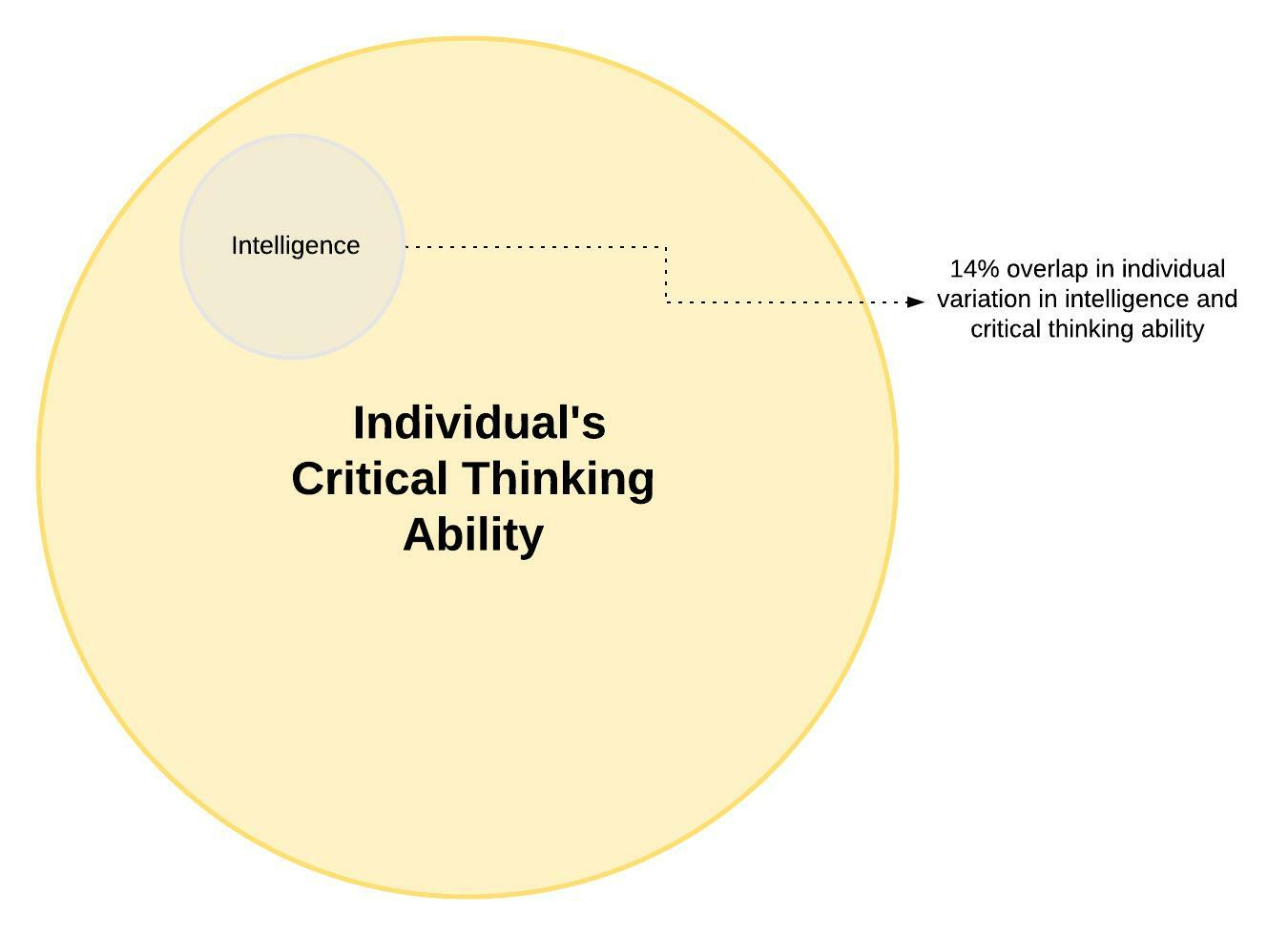

Research studies have shown that critical thinking ability is an even better predictor of life decisions than intelligence[4], and also, that better critical thinking predicts wellbeing and longevity.[5] In other words, after mastering this text, you’ll experience fewer bad things in life, you’ll be happier, and you’ll live longer – now that’s a sales pitch! This is especially good news for dummies like me. It means that no matter how smart you are, being good at critical thinking can improve your life. Intelligence still plays a minor role, but it’s actually quite difficult to do much about that, whereas critical thinking is very malleable, which means it’s changeable and can be improved. Of course, intelligence can help with critical thinking and vice versa, but interestingly, there’s only about a 14 per cent[6] overlap in individual variation in intelligence and critical thinking ability, which is quite encouraging.

We are not Automatically Good at Thinking

Let’s look at our second reason for improving critical thinking. At first blush, our inability to think very well might seem counterintuitive. How could we be bad at something we do all day and have been doing our entire life? Doesn’t ‘practice make perfect?’ In the case of skilful technical activities, practice does not make perfect at all. In fact, practice only reinforces and ingrains bad techniques and habits.

Thinking about other skilful practices can help make sense of this. Martial arts are a good example. Practising a technique incorrectly for 1,000 repetitions doesn’t make you any better at the move. One of my favourite coaches once said, ‘Every time you practice a move less than perfectly, you get a little worse at it. Every time you practice a move perfectly, you get a little better at it’. This was from Ryan Hall who is a UFC fighter and former Brazilian Jiujitsu world champion. Thinking is a lot like this.

Don’t worry, it isn’t all doom-and-gloom. As I pointed out earlier, critical thinking is a collection of skills that are very learnable and can be cultivated through practice. However, without learning and practice, we’re simply not automatically active, purposeful, careful, open, evaluative, methodical, reasoned thinkers. One of the first steps to being more critical in our thinking is just to recognise that our natural default approaches to thinking are less than optimal. And calling them ‘less than optimal is being generous’. They can actually be quite disastrous as we fall victim to a thousand blind spots, biases and prejudices, and sloppy gullible habits. Through practice, we can sharpen and strengthen our critical thinking skills, the same way a weightlifter develops strength through repetitions (I keep coming back to this analogy to really drive home the need for repetitive practice).

Another selling point to critical thinking is the generality, applicability, and scope of these skills. This means critical thinking isn’t restricted to one specific content or subject area. You can apply the skills you learn in this text to any area of your study, your work, or your life. Most of your undergraduate courses will focus almost exclusively on subject knowledge that can rapidly go out-of-date. For example, textbooks on emotion, psychopathology, cognition, and counselling that existed when I was a student 10 years ago are now long out-of-date. In contrast, the knowledge and skills you learn in this text won’t just outlast the subject knowledge you learn in psychology, but will make you better able to properly absorb new information and be more likely to succeed in any discipline with such fast-changing knowledge. Sharpened critical thinking skills can aid you in properly judging the credibility of new claims in your own field, and also in appraising claims in other fields that you don’t necessarily have a lot of knowledge in. My PhD supervisor always said to me that university study wasn’t about memorising facts, but about perfecting students’ ‘bull… detector’.

Living an Examined Life

Let’s look at the idea of living an examined life. From the above two points, you can see that there is much to be gained personally by developing your critical thinking skills. In general, you can think of life with critical thinking skills as a more examined existence as you introspect, evaluate, and interpret yourself and the things around you with a much sharper set of lenses. The Ancient Athenian philosopher Socrates (who we’ve come across already in this text) went even further and actually claimed that an unexamined life wasn’t even worth living. This famous saying was delivered by Socrates while he was on death row, and it highlights the necessity of self-reflection and self-scrutiny in giving meaning to our lives. The Athenians had a gutful of his preachy-ness and sentenced him to death. The point is that to maximise the potential of our lives to be meaningful, we need to think deeply, intentionally, and be open-minded and inquisitive about our own thinking. If I were to extend this advice to one of the core messages of this text, I would say that ‘Unexamined assumptions are not worth holding or believing’ since they can only wreak havoc on our thinking and lives. Socrates would advise that we question all our assumptions daily, and this practice has to start by actually figuring out what they are.

In this way, critical thinking is a type of disposition or attitude we can adopt and apply to improve the overall quality of our life. We should continually examine our beliefs, assumptions, information, and values to ensure we’re maximising our thinking power.

An Obligation to be Critical Thinkers

Critical thinking isn’t just about improving our own lives. We actually have something of a moral and social obligation to be critical thinkers. In addition to the reasons I’ve already listed, that mostly involve the way the condition of our lives can be improved by critical thinking, we also have obligations outside ourselves. In other words, there are important altruistic, in addition to self-serving, reasons to improve our critical thinking. To be contributing citizens in a modern democratic society, we actually need to be able to think critically about the issues that matter to us and the people we care about. In line with living an examined life, we need to be clear about our own values, our motives, and the reasoning behind them. Our families, communities, and democratic societies actually depend on us as citizens to be able to carefully reflect on a wide range of issues, critically appraise information and arguments, judiciously weigh options, and to act and vote according to our values for the best outcome. In the digital age where we spend a huge chunk of our lives on social media, it’s more important than ever that we engage with ideas from a critical standpoint. This makes critical thinking training a social obligation as well as a tool for self-improvement.

Who Should Study Critical Thinking?

The short answer to the question of who should study critical thinking is ‘Anyone who thinks.’. A slightly longer answer might be ‘Anyone who wants to be successful in study, career, relationships, and anything in life.’. The point to these simplistic answers is that it’s unlikely anyone wouldn’t benefit somehow from training their critical thinking skills. The moral of the story here is that if you think, and your thinking impacts you (which is to say everyone), then you’d benefit from thinking better.

As Canadian clinical psychologist and professor Dr Jordan Peterson explains in his guide to writing essays:

Those who can think and communicate are simply more powerful than those who cannot, and powerful in the good way, the way that means “able to do a wide range of things competently and efficiently.” Furthermore, the further up the ladder of competence you climb, with your well-formulated thoughts, the more important thinking and communicating become. … So, unless you want to stay an ignorant, unhealthy lightweight, learn to write (and to think and communicate). Otherwise those who can will ride roughshod over you and push you out of the way. Your life will be harder, at the bottom of the dominance hierarchies that you will inevitably inhabit, and you will get old fast.

Therefore, a more selfish-sounding answer to who should study critical thinking might be ‘Whoever wants to actually get ahead, be successful, be persuasive, make a difference, and generally win at life’.

I’ve reiterated many times so far that critical thinking is a complex skill that’s learnable and trainable, but requires dedicated practice. You won’t get much better at it just by reading this textbook, without doing any actual practice. Unlike some highly technical skills such as flying a fighter jet or coordinating rover landings on Mars, critical thinking is an equal-opportunity skill set that anyone can improve with the right information and commitment.

Contrary to popular opinion, most of the thoughtless things people do aren’t really due to a lack of intelligence – though there is something deeply satisfying about concluding that other people are ‘simply morons’. We all have that unique human knack for doing stupid things. I’ve searched the house for 30 minutes looking for my glasses, only to realise that I was wearing them. I’ve even scrambled around in bed searching for my phone in the dark, aided by the light from the phone screen. One fateful day, I was shaving and decided to clean the end of my razor with my finger by swiping across it. I haven’t made that mistake twice. I like to believe I’m not alone in committing these kinds of goofs. My wife particularly enjoys the meme trend ‘Why women live longer than men’, which shows photographs of men doing a range of ridiculous things – mostly involving ladders. These misadventures can be chalked up to a combination of bravado and a general absence of careful thinking. While they’re mostly trivial and funny, there’s a more serious side to failures in careful thinking. Reading through the list of winners of the aptly-named ‘Darwin Awards’ is a great way to scare yourself ‘smart’ and motivate you into some serious thinking training. As the name implies, these awards commemorate those who improve our gene pool–by removing themselves from it in the most spectacular way possible. In these cases, the goofs end up costing the poor chumps their lives. These tragic failures of thinking illustrate that while the actions are most definitely thoughtless, the people who commit them are not necessarily unintelligent, but just like everyone, they’re very prone to not being careful and meticulous in their thinking. As I have said before, critical thinking isn’t our natural default mode of thinking. For this reason, thinking skills are something that everyone could benefit from working on. It may even save their life.

Critical Thinking in Modern Society and the Workplace

Let’s consider the role of critical thinking in modern society and the workplace. Critical thinking skills are becoming more and more important in our fast-paced, media-saturated, and increasingly politicised information landscape.[7] Never before have we been inundated with so much information, news, opinions, options, and ideas. And never before has this type of downpour been so rapid – almost instantaneous. Sometimes, the flood of data seems impossible to escape. As a result, it has never been so important to have fine-tuned and razor-sharp thinking skills with which to navigate this environment. These changes in our information landscape have been dramatic and swift, and are set to accelerate into the future. Presently, there is too much information, news, and commentary to absorb and process, and so we have to make daily choices about who we expose ourselves to and who we ignore. As I emphasised previously, we all need to be very careful not to box ourselves into being exposed only to sources that share our worldviews and our political or religious perspectives. This is quite a modern problem in the grander scheme of human history. Within the space of about 80 years, the population of the world has gone from being mostly illiterate to active users of the internet – the greatest information source ever created.[8] This is quite a shocking change in such a short time. No more than 80 years ago, more than half of the people on the planet couldn’t even read or write, and today the majority of adults in the world are active internet users – not simply have internet access but are active users of it. And yet, despite this surge in engagement with information among the majority of people, we’re living in what has been nicknamed a ‘post-truth era’.

Sadly, our post-truth era has devastating consequences. We now have to grapple with a host of social, economic, and environmental problems that are caused by a lack of critical thinking. To cite only a couple of examples from Jeff Jason, we live in an age where we must deal with unvaccinated populations nurturing the spread of previously eradicated diseases, and an age in which NASA needs to publicly state that Mars is actually not a secret child labour slave colony.[9] The only way to get humanity back on track is training more people in critical thinking.

We’re bombarded from all directions with a dizzying avalanche of information and ideas, and amid this storm, it’s more urgent than ever that we practice skilled and active interpretation and evaluation of observation, communication, information, and argumentation. In plainer terms, we need critical thinking to filter useful signals from all the noise. Currently, the signal-to-noise ratio is largely unknown, but it’s safe to say that most of what we encounter is useless noise – or even worse, is unwanted, biased, rhetorical propaganda, clickbait, and agenda-driven ‘news’. Without critical thinking, there’s no way to determine how much of the information you’re bombarded with is actually useful and accurate – that is, there’s no way to reliably pinpoint the meaningful signals.

It isn’t that this challenge is completely new to humankind, but it’s becoming more and more urgent as the volume of information and rhetoric accumulates and accelerates daily. Your attention is a hot commodity in the twenty-first century, as a thousand corporations and interests vie to secure your engagement in their products. You’re the target of a billion-dollar arms race for your opinion, your engagement, and ultimately, your clicks and votes. This new business model (some are referring to it as an ‘attention economy’) has led to media companies employing teams of cognitive scientists, social scientists, and statisticians to calibrate their media platforms in a way that ensures they have the best chance of hypnotising you and manipulating your human vulnerabilities (mostly through emotion manipulation) to keep you glued to their content. This is addiction science weaponised to seduce the masses so they can make your attention a commodity for them to sell to other third-party companies.

Be aware that the information you consume has almost always been heavily processed, and processed information is just as bad for you mentally as processed food is for you physically – and I would argue, it’s even more addictive. Part of your homework for this chapter is to listen to the discussion about ‘What is technology doing to us?’ on the Making Sense Podcast with Sam Harris.[10] The bottom line is to learn to think critically, or risk becoming a victim to these forces.

In broader commercial terms, information itself is a major commodity in the twenty-first century global economy. This is why people call it the ‘Information Age’. We’re entering what is being called the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’[11], which has at its heart information and information technologies. And all the while, it’s becoming less and less clear what actually counts as information. One result of this is that employers are becoming more sensitive to the importance of critical thinking among their employees. Dedicated manuals and guides have now been developed specifically for business to adopt critical thinking approaches. In fact, critical thinking is now considered one of the primary skill sets required for success in many industries.[12]

Not too long ago, the top ten skills were ranked by global employers and half of them relate directly to critical thinking. Rounding out the top three are complex problem-solving and creativity, both of which are actually core components of critical thinking and will be covered in this text. Not surprisingly, of the top ten skills listed, half of them relate directly to critical thinking as we will conceptualise it in this book.

For example, number 1 (complex problem-solving), number 2 (critical thinking), number 3 (creativity), number 7 (judgement and decision-making), and number 10 (cognitive flexibility) are all part of our broader conception of critical thinking and will be covered in this text.

Top 10 skills identified by the World Economic Forum:

- Complex Problem-Solving

- Critical Thinking

- Creativity

- People Management

- Coordinating with Others

- Emotional Intelligence

- Judgement and Decision-Making

- Service Orientation

- Negotiation

- Cognitive Flexibility.

I realise that the answer to the question that motivated this section ‘Who should study critical thinking?’ has now trespassed on the content of the previous section ‘Why study critical thinking?’, but the two answers are very closely intertwined. There are so many advantages to studying critical thinking that any time I talk about particular applications, it will seem like I’m just in ‘sales’ mode again. In all honesty, there really are no downsides to working on a critical thinking toolset. That’s probably all the hyping you’re willing to put up with from me this early in the text, so I’ll curb my enthusiasm here.

How is Critical Thinking Improved?

We can’t leave the first chapter without mapping out, in broad strokes, how critical thinking is developed and improved. We have the entire book to get into the nitty-gritty, but here we can outline the broad steps that are involved.

Just like repairing a car engine, the first step in improving your critical thinking involves examination and understanding. To bridge the gap between our current state of thinking and our goal state (which is critical thinking), we need three pieces of information:

- We need to understand our current state of thinking.

- We need to understand what the goal state looks like.

- We need to know how to progress from our current to the ideal state.

Therefore, the beginning of critical thinking is self-reflection and awareness. Simply put, we need to think about thinking itself. To achieve our ends, there’s quite a bit of theory to be covered in the book, and some effort at being mindful will be required. The chapters in this text will outline more about thinking, how it operates, and how/why it goes awry. This first step then is all about knowledge and comprehension, which is a necessary launching pad to being able to ‘do’ critical thinking.

The second step is practice and application. This is as important as theoretical learning, but it’s often overlooked. You need to exercise your critical thinking muscles for them to strengthen. This means actively practising what you’ve learned as you go about your day. Thinking is practice, not just theory. Like the martial arts analogy I used above, critical thinking is a comparably disciplined art. Both are complex skill sets that cannot be mastered by mere theoretical learning. You might actually die if you enter a UFC fight having only read an instruction manual on how to fight. Critical thinking is a similar in that your ability will only improve with dedicated practice. In addition, you should be attentive and open to new opportunities to practice what is being taught in each chapter.

This book will attempt to cover both steps with lots of theoretical information on thinking better, but also with activities for you to do along the way so that you can practice and master the skills. Don’t fall for the temptation to skip practical exercises, as the effort you put into these will pay off.

Final Word for Chapter 1

Let me leave the last word for capturing the sentiment of this chapter – and also this whole textbook – to Voltaire, who is considered one of the greatest writers in history.

Let’s arm ourselves with an arsenal of powerful critical thinking tools, and begin deconstructing the edifices of superstition and ignorance that are the impetus behind this fanaticism.

Additional Resources

Videos

Access a playlist of relevant videos by scanning the QR Code. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

Access a playlist of relevant videos by scanning the QR Code. Take the time to watch and think carefully about their content.

Fallacy posters and flashcards

Print and/or study the fallacy posters and flashcards:

- FUN FACT: This is actually happening according to a very interesting neuroscientist I had the pleasure of hearing speak: Dr Divya Chandler. It’s called Brain Hacking ↵

- Facione, P.A. (1990). The Delphi Report. The California Academic Press. [1998 printing]. ↵

- Feynman, R. (1974). Cargo Cult Science. Engineering and Science. June, p. 12, para. 6. ↵

- Butler, H. A., Pentoney, C., & Bong, M. P. (2017). Predicting real-world outcomes: Critical thinking ability is a better predictor of life decisions than intelligence. Thinking Skills and Creativity. 25, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2017.06.00 ↵

- Grossmann, I., Na, J., Varnum, M. E. W., Kitayama, S., & Nisbett, R. E. (2013). A route to well-being: Intelligence versus wise reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(3), 944–953. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029560 ↵

- Butler, H. A., Pentoney, C., & Bong, M. P. (2017). Predicting real-world outcomes: Critical thinking ability is a better predictor of life decisions than intelligence. Thinking Skills and Creativity. 25, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2017.06.005 ↵

- The world may have always been politicised, and information has always been a political tool. but never before have there been so many people interacting with, and influenced by this process. ↵

- In 1940, 58 per cent of the world couldn’t read and write. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/09/reading-writing-global-literacy-rate-changed/ ↵

- Jason, J. (2017, August 10). Confirmation bias making you dumber, and what to do about it. Medium. https://medium.com/@umassthrower/confirmation-bias-sucks-a7bc989d3fd2 ↵

- Harris, S. (Host). (2017, April 15). What is technology doing to us? (No. 71) [Audio podcast episode]. In Making Sense. https://www.samharris.org/podcasts/making-sense-episodes/71-technology-us ↵

- Schwab, K. (2016, January 16). The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means, how to respond. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond ↵

- Ranked by the 100 largest global employers in target industry sectors (as classified by the World Economic Forum), published in the 2016 The Future of Jobs report. ↵