Introduction

Welcome to this textbook on critical thinking and scientific reasoning. The scope of this text is admittedly very ambitious, so let’s put it into the most general terms: You have been gifted with a 1.5 kilogram supercomputer between your ears, and unfortunately, it never came with anything like an operating manual. Therefore, the broad purpose of this text is to help you learn how to get the most out of this extraordinary device.

Also, it’s important to remember that this extraordinary device doesn’t operate in a vacuum (i.e., in isolation) but interacts with an outside world and other individuals and our cultures and societies in ways that are fraught with dangers and tripwires. This context is becoming increasingly more complex and more combative as people try to actively exploit the vulnerabilities in our thinking to gain better control over us. The Oxford Dictionary declared ‘post-truth’ to be the word of the year in 2016, which suggests that, in modern times, the way people feel and what they believe often has a stronger influence on public opinion than actual facts and evidence. Since 2016, this situation has become worse, not better. As a result, there is no more important point in history or in your own life for you to buckle down and invest some real time and energy in mastering the art of thinking.

According to Aristotle, ‘man is a political animal’, meaning we are innately geared towards social organisation and to be influenced by others, and in turn, influence others. Famous philosopher Fredric Jameson went further and wrote that everything is influenced by social and historical forces and ultimately, even seemingly non-political aspects of life are shaped by the way power is exercised and distributed throughout society. This insight tells us that all we are, and all that we do, is geared towards influencing and being influenced. The term ‘political’ here is meant broadly, not simply to refer to politics and government and so on, but to show that all human endeavours and interactions are carried out in order to convince and influence. So, if you want to be good at this game that consumes us, we must learn to think and communicate effectively.

Another crucial thing to keep in mind as we travel through these lessons is that they are about your thinking as well as that of others. I am pointing out the seemingly obvious here because in the past, students have often discussed this content solely in terms of how it helps them understand the thinking of others or how it helps them argue more convincingly and win debates. But the material here is intended for you to use to get to know your own thinking and improve it. The first step to becoming an expert thinker is to interrogate your own thinking – your own perceptions, beliefs, assumptions and reasoning. All the pitfalls in thinking that we’ll discuss in this book apply to our thinking as much as they do to others’. Modesty is often needed for this endeavour to be successful, and we have very good reason to be modest, since every belief or perception we have is nothing but an interpretation. Each of these interpretations are shaped (i.e. distorted) by lenses representing our language, history, expectations, beliefs, desires, worldview, etc. As you read, resist the temptation to constantly apply what you are learning to the thinking of others, and instead turn your analysis inwards. Every disagreement is nothing more than a competition over whose interpretation will become orthodoxy – whose perspective wins out. Rather than try to win arguments or defend your own perspectives, look to be challenged and learn to lose arguments better – that is, in a way that matures your own thinking.

We have a lot of content to get through. Some of it will be more elementary, though I hope it will still be interesting, while other parts will be more technical and challenging. Regardless, my aim is to always be informative. As we progress through the content, some material might, on the surface, seem irrelevant to our purposes. For example, at different points, you might be wondering ‘Why so much talk about language?’ or ‘Why are we learning so much logic?’. However, this book is all about thinking and in a way, almost all of the concerns about thinking boil down to language, truth and logic[1]. So, of course my intention is that, by the end of this book, you’ll have mastered all three, and more.

If you feel yourself getting bogged down in the details, remember to step back, take a breath, and stay focused on the prize at the finish line (bulletproof thinking!). Despite the volume of technicalities to be learned, remember to keep a healthy sense of wonder. In the wise words of Francis Bacon:

You might also wonder why I’ve incorporated so many historical events and figures into this book. The reason is because I’m a devotee of experimental science, and history is the greatest experiment ever conducted. It’s like an examination of thinking conducted over millions of replications, at millions of sites, and through millions of time points. Therefore, observing the lessons of history about the fault lines in our thinking, and absorbing the insights of great past thinkers, is a shortcut to mastering our own thinking today. When it comes to being an expert thinker, we don’t need to reinvent the wheel – we just need to study the lessons and experts of the past who had perfected it already.

One more metacomment about the text before I get into the meat of it. Throughout this book, you’ll learn a lot of new terms and concepts, and these can sometimes seem daunting or even distracting. You might wonder at some points, ‘Why is he explaining these concepts when we could have learned the main points without them?’. This is a valid concern, but I want to assure you that learning new concepts is vital to your thinking skills – so vital that I will repeat this point several times through this book. Concepts are the building blocks of our thoughts, and every time you learn a new concept, you gain a new tool (or a new thinking power if you like). The more concepts you know, the more tools you have available to put to work in navigating your life. Concepts are the most powerful thinking tools I can give you, and the more concepts you absorb from this text, the smarter and better at thinking you’ll become.

This textbook has 8 broad modules. This is divided into 10 chapters, though since 2 of the modules ended up being so big, I cut them in half. To prepare for what is to come, let’s have a look at what each chapter will teach you.

The following graphic is an overview of all the content broken into the 8 chapters. When you’re down in the trenches with some mind-bending concepts in a particular chapter, it can be helpful to come back and look at this outline and remind yourself what the broad picture is and how each chapter’s content attempts to get you to your end goal.

Now for something rather boring but absolutely necessary. Later in the book, we will have a whole chapter devoted to the power of language and the necessity of arming ourselves with new conceptual tools in order to be formidable thinkers. For now, I want to briefly argue in favour of the necessity of spending extra time learning the new conceptual tools this book will equip you with.

Skilful applications or techniques in critical thinking are merely the application of concepts. That means becoming skilful in thinking is nothing more than learning new concepts and ways of applying them. Concepts are new lenses to use in order to see things, and to see them in specific ways. In this way, understanding concepts such as the make-up of propositions, arguments, worldviews, models, fallacies, inductive and deductive reasoning, cognitive biases and moral perspectives are like acquiring new lenses that actually enable you to see more, see further, understand more and then do more than you could have previously. Armed with the new lenses you’ll acquire in this text, your thinking becomes markedly more powerful.

In the following chapters, we will come across subsections surrounded by an orange box (orange like a traffic light, meaning slow down and absorb the definition carefully). These subsections contain key ideas and concepts that are absolutely essential for you to understand before proceeding to deeper, more complicated material, so make sure you invest time becoming confident with these terms before moving through the chapter. At the start of each chapter, I will also briefly list the new concepts that you need to learn in order to master the chapter’s content. You can refer back to this list after studying the chapter as a way to check your understanding. At the end of the textbook, I will collate all the technical terms to provide easy reference for you if you forget one or want to familiarise yourself with a term later.

If any of my explanations here don’t quite click, fear not! A comprehensive glossary awaits you at the end of the book, diving deeper into each key term. In the glossary, I’ve taken a fresh approach, offering alternative explanations and engaging examples to pique your interest and solidify your understanding. Consider it a valuable companion to your studies—a handy tool to reference whenever you need a little extra clarity or inspiration.

There are also a few light green sections I’m calling Explanation Box, which will attempt to provide additional definition and illustration on some issues I have found students particularly struggle with. For those of you who have a good grasp of the ideas, these sections might only seem like pointless repetition, but they may also be valuable ways to deepen and strengthen your understanding.

The take-home message here is that this text builds on early concepts to introduce more complicated ones in later sections. For this reason, when you come across a term you don’t understand, don’t just keep reading. Stop and spend some time becoming familiar with the term by looking it up at the end of the book, Googling it, asking on the forum, etc. This way, you won’t prevent yourself from benefiting from more complicated material later on that might require your firm grasp of certain concepts.

Our Accompanying Cast

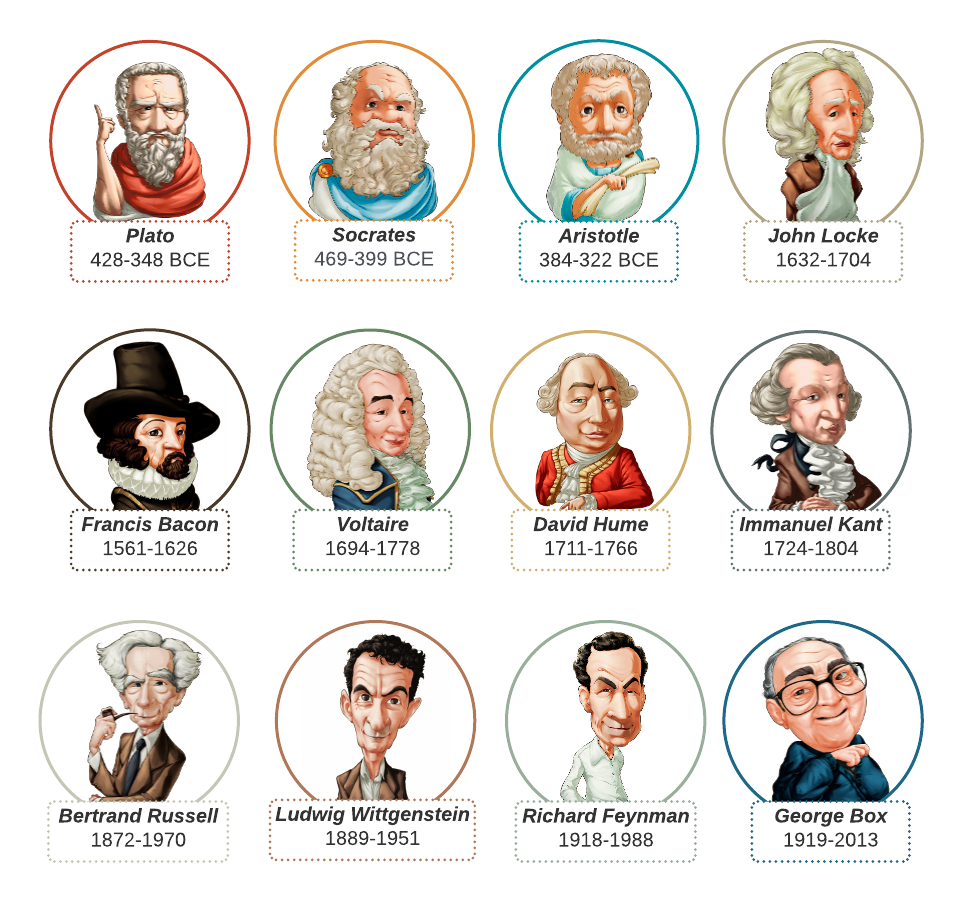

Along the way, we will meet a range of fascinating and brilliant characters that have been some of the greatest thinkers in history. Let’s face it, there is nothing really new in the science of thinking. As Alfred North Whitehead famously observed, the Western philosophical tradition is essentially ‘a series of footnotes to Plato’.[2] This means that much of the knowledge within these pages has been taught and learned before. Yet, because critical thinking doesn’t come naturally, each of us must embark on our own journey of discovery and understanding.

To help us along the way, we will hear some pithy insights from some of history’s greatest and most fascinating critical thinkers. I will include a very short bio for each, so you know something about them as they pop their heads in throughout the text. This cast of characters includes philosophers, poets, mathematicians, social reformers, scientists, politicians, soldiers and convicted felons. Look out for the following characters and heed their wise words:

- Which is actually the title of an awesome book by A. J. Ayer https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language,_Truth,_and_Logic ↵

- Whitehead, A.N. (1929). Process and reality. An essay in cosmology. Gifford Lectures delivered in the University of Edinburgh during the session 1927–1928. Macmillan. ↵