Addictions

John Falcon

Abstract

This chapter will discuss the complexity of chemical and behavioural addictions. It will provide counsellors with in-depth knowledge of the field of addictions including both chemical and behaviour addictions. It will focus on what motivates clients seeking assistance and what counsellors need in terms of skills and knowledge in the interventions for addictions. Applying an attuned therapist approach will be offered. Counsellors will develop sensitivity to the stigma and shame surrounding addictions, and the social exclusion experienced by individuals and their families who have a vulnerability to addictions. Highlighted in the chapter is the prevalence of addictions both globally and in Australian society, including the overarching framework for services and interventions. The chapter will examine physiological, psychological, neurobiological, and sociological aspects of addictions, understanding current categories that are present. The aetiology of addictive behaviours will be outlined in terms of epigenetics and neuroscience, the effects of the mechanism both in the brain and a practical application in psychotherapy. Assessment protocols and case conceptualisation will be offered as a road map for client interventions.

Counsellors will learn and apply the major evidence base and practice-based models and interventions that fit clients’ needs, considering mental health issues and trauma. Attachment theory, motivational interviewing (MI), acceptance commitment therapy (ACT), neuropsychotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), and couples and family interventions, will be reviewed. Ongoing intervention planning including relapse prevention and support will be outlined. Importantly, self-care strategies will be offered to counsellors for best practice in combating burnout. Resources are provided throughout the chapter in order to support your further research into these areas.

Learning objectives

- Use the terminology and understanding of the concepts of addictions, both chemical and behavioural.

- Apply a case vignette in the assessment, intervention, and relapse/craving plan development.

- Apprehend the global and Australian statistics on the issue of addictions.

- Identify the challenges that counsellors face with current issues in policy and trends explaining the risk factors and variety of-risk populations’ conditions, including the family roles in the family system.

- Articulate the current approaches in addictions and identify a variety of options, including the use of various pharmacology.

- Evaluate a variety of theories and develop assessment, case conceptualisation, and referral skills appropriate to clients with addictions.

- Critically analyse the attachment theory and how it applies to the aetiology of addictions and effects on the brain.

- Discuss how shame and stigma interfere with intervention and how to motivate clients to intervention for addictions.

- Develop an integrative approach in addictions intervention, including biopsychosocial, mental health issues, and the effects of trauma mental health and the effects of trauma, and apply advanced theoretical knowledge for relapse prevention strategies and ongoing continuing care plan.

- Develop self-care strategies and protective strategies and identify the benefits of being an attuned practitioner in fostering a therapeutic alliance.

Introduction

Research into addictions has focused on two main areas: what causes addictions and how do we treat addictions. What causes addictions? Initially, two basic models emerged—the biological or the disease model and the behavioural model. The disease model describes an addiction as a disease with biological, neurological, genetic, and environmental sources of origin. The behavioural model of addiction sees addiction as involving a compulsion to engage in a rewarding non-substance-related behaviour—sometimes called a natural reward—despite any negative consequences to the person’s physical, mental, social, or financial well-being. Rather than adopting a specific model, this chapter draws on the interplay between four main areas: physiological, psychological, neurobiological, and sociological aspects of addictive behaviours.

The overlapping feature common to all behavioural addictions is the failure to resist an impulse or urge, leading to persistent engagement in the behaviour (e.g., online gambling, sex addiction, disordered eating, avoidance addictions including compulsive use of the internet, mobile phone, video gaming, and shopping addiction, despite returning harms (Grant et al., 2010). A unified approach to intervention that is research enhanced is offered in this chapter as a method of assessing intervention and its effectiveness.

Counsellors need to have a framework to identify the aetiology and work clinically collaboratively with individuals who come to therapy exploring individual and relational scripts, an important part of attachment-sensitive counselling (Schore, 2003). Shore talks about a “two person” psychology where right brain-to-right brain, embodied, affective, autonomic change between therapist and client becomes central to the therapeutic process (Schore, 2003). This is the basis of being an attuned counsellor. Attachment theory is central to working with clients with addictions and has become very useful in recovery. As Oliver Morgan argued, in his ground-breaking work Wired to Addiction, addiction is an attachment disorder (Morgan, 2019). Attachment therapy can be used to shift someone’s emotional distress, external mood modifiers chemical and behavioural forms. Therefore, counsellors need to critically evaluate themselves with current approaches to emotional regulation and addiction through attachment theory. The rapid, implicit emotional processing of deeper brain structures requires the therapist to engage in psychotherapy that goes well beyond the traditional cognitive–behavioural understanding. Studies have shown that attachment styles from client’s interaction with their primary caregivers determine the child’s brain structure. The moulding of approach and avoidance patterns drive strong neural connections. Therefore, creative interventions and understanding are important ways of changing attachment patterns (Siegel, 1999).

Counsellors also need to consider mental health issues and trauma as important pathways to addictions intervention. Supporting clients more comprehensively is the focus of this chapter utilising both neuroscience and traditional models. Counsellors need to have a competent understanding of the positive effects of a unified approach in order to work with clients with substance/s use and addiction. It is important for counsellors to know that trauma and addictions go hand-in-hand. Intolerable emotions and psychological pain coupled with self-medication with alcohol, drugs, food, sex, gambling, and so on (Dayton, 2000, p. 18) become a survival mechanism for clients with trauma and mental health issues. We need to look at the root of emotional problems and trauma and most often the root causes are found in the family system where addictions and trauma have eroded the infrastructure (Dayton, 2000, p. 307). Attachment theory helps to make those links necessary for counsellors to understand.

Importantly, counsellors need to establish an understanding of their limitations when working with clients with addictions. Equally important are the challenges faced in practice with clients with addictions and the need to develop protective strategies through self-care and clinical supervision. In the meta-framework of neuropsychotherapy, clinical practice is informed by insight that has been gleaned from contemporary neuroscience and related disciplines. These insights lead to a key challenge to traditional approaches from Grawe, a key researcher in neuropsychotherapy. He argues that “we ought to conduct a very different form of psychotherapy than what is currently practiced” (2007, p. 417). This includes engaging in deliberate practice to enhance therapeutic effectiveness and self-care as central foci.

Underpinning the contemporary work of counsellors three important principles are emphasised. First, we need to understand and apply research in our work, i.e., be research informed. Second, we need to tailor our approaches to addictions to the individual needs of our clients. Third, we need to work as attuned counsellors and see the complexity of addictions and associated mental health issues. Rather than applying a specific model, the primary concern of working with clients with addictions must be the individual needs of the client and always working within a supportive therapeutic relationship (Swisher, 2010).

Case study: The story

George is a 40-year-old who presented in counselling due to his wife’s insistence after a visit to the GP. George’s GP was concerned with the depression symptoms that George has had for the last 6 months. He has been isolated at home and at work and has sleep problems, irritability, not getting projects done at work, unable to concentrate, withdrawing from family, and relying on alcohol to reduce feelings of being overwhelmed and unhappy. George has been married for 5 years and they both want a child, but George says he is not ready until work improves. He has been in his job now for 2 years as a manager in an electrical engineering aerospace company.

George’s wife reports that George has become unhappy, isolated from her, and hard to talk to. He has increased his drinking and she is worried when he could not go to work due to his drinking. She has given him an ultimatum that he seeks counselling, or she will leave the marriage. George states his drinking is normal. He drinks with his friends 4–5 times a week after work drinking 6-7 beers and, on the weekends, while watching sport where he drinks about 6-10 beers. He and his mates do online bets and his wife says that is also a problem with their budget. He blames his increase in drinking due to pressures at work and from his wife about having a child.

George’s mother has had a diagnosis of depression for most of his life and he is ashamed of her condition and, therefore, does not believe he is depressed like her. His rationale is that it is just stress at work. His mother has been on depression medication for most of his life and that scares him. She was distant when he was growing up and George tried to assist her when she had depressive episodes. She had times of suicide ideation, but George denies any suicide ideation or attempt.

George’s father is a heavy drinker and so is his grandfather and George believes it is part of the family culture. His father is very demanding of him to succeed in his small business and was always distant when George was growing up because he was busy.

George was diagnosed at primary school by the psychologist with the learning disability dyslexia and identified as on the autism spectrum. He was put in a special school, which his father was against, but his mother insisted and supported him. He felt some shame and a stigma about being in that special school yet did well in maths and technology. He has always had poor social interaction and was a lonely child with few friends at school. At work he fears being rejected by his team members, so his managerial style is to be laisse faire. He states he feels out of place in most social situations and drinks to avoid discomfort and rejection.

George is ambivalent about his drinking problem and blames his wife for pressuring him. He does not like being diagnosed as depressed due to his mother’s history but has low motivation for intervention.

An intervention plan will address his lack of motivation with drinking and monitor his depression symptoms. The treatment plan will depend on his assessment results considering his high level of drinking and depression symptoms. Other compulsive behaviours will be considered in the overall plan. Couples therapy will be offered to address stressors and improve communication in the marriage.

Toward treatment in the 21st century

We will now look at developing greater understanding of the field of addictions. This involves identifying the prevalence of addictions, both globally and locally. Policy frameworks will be presented along with risk factors that have negative impacts on addictions. Current psychopharmacological interventions for craving, withdrawal, and tolerance will be examined as well as new neurobiological approaches.

We begin by looking at definitions of substance use disorders and addictions which have changed substantially over the years. The literature has moved from addiction to dependency and now substance use/addiction. The term substance use disorder was introduced by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, 2013) and refers to the recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For this chapter, we define a drug as any non-food substance illicit (illegal) or prescribed. We define a drug user or substance user as anyone who takes drugs which are illicit or prescribed in order to alter their function or state of consciousness. Addiction is the fact or condition of being addicted to a particular substance or behaviour where there is a presence of dependency, craving, compulsion, tolerance, and withdrawal. Thus, addiction is a neuropsychological and physical inability to stop consuming a chemical or being involved in a behaviour causing harm to self and others.

Prevalence of addictions

The prevalence of substances in society is explored with both global and Australian figures.

Globally, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) identified the following:

- substance use was responsible for 11.8 million deaths in 2017

- tobacco risk factor for early death in 11.4 million instances

- over 350,000 deaths from alcohol and illicit drugs use disorders (overdoses) each year

- alcohol and illicit drugs addiction accounted for 1.5 % of global disease burden, with some countries identified as over 5%

- over 2% of the world population has an alcohol or illicit drug addiction

- the USA and several Eastern European, more than 1-in-20 (5%) were dependent

- alcohol was more common in Russia and Eastern Europe (IHME, Global Burden of Disease, 2017).

The figures for Australian use are from the 2016 National Drug Strategy Household Survey: Substance abuse in Australia (AIHW, 2017).

Illicit drug use:

- more than 3 million Australians use an illicit drug

- about 1 million Australian misuse a pharmaceutical drug every year

- more than 40% of Australians over 14 years old have used an illicit drug in their lifetime

- more than a quarter of people in their 20s have used an illicit drug each year

- about 1 in 8 Australians had misused at least 1 illegal substance in the last 12 months and 1 in 20 had misused pharmaceutical drugs

- in 2016, the most commonly used illegal drugs used at least once in the past 12 months were cannabis (10.4%), cocaine (2.5%), ecstasy (2.2%), and meth/amphetamines (which includes “ice”) dropped to 1.4% from 2.1% in 2013.

Alcohol use:

- 8 in 10 Australians had consumed at least 1 glass of alcohol in the last 12 months

- among recent drinkers:

- o about 1 in 4 (24%) had been a victim of an alcohol-related incident in 2016

- o about 1 in 6 (17%) put themselves or others at risk of harm while under the influence of alcohol in the last 12 months

- o about 1 in 10 ((%) had injured themselves or someone else because of their drinking in their lifetime.

Polydrug use:

- 39% of Australians either smoked daily, drank alcohol in ways that put them at risk of harm or used an illicit drug in the previous 12 months

- 2.8% of Australians engaged in all 3 of these behaviours

- 49% of daily smokers had consumed alcohol at risky quantities, either more than 2 standard drinks a day on average or more than 4 on a single occasion at least once a month

- 36% of daily smokers had used an illicit drug in the previous 12 months

- 58% of recent illicit drug users also drank alcohol in risky quantities (either for a lifetime or single occasion harm) and 28% smoked daily.

The statistics so far do not include other addictive behaviours and their effects. However, we do have AIHW (2021) statistics for gambling:

- Australians lost approximately $25 billion on legal forms of gambling in 2018-2019

- social costs of gambling include adverse financial impacts, emotional and psychological costs, relationship and family impacts, and productivity loss and work impacts-estimated around $7 billion in Victoria alone

- the national Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey estimated that in 2018, 35% of Australian adults aged 18 and over, spent money on one or more gambling activities in a typical month, a 4% decrease from 39% in 2015

- HILDA 2015 and 2018 identified gambling activities as Lotto or lottery games (30% and 27%), instant scratch tickets (8.5% and 6.3%), poker machines/pokies (8.1% and 7.4%), betting on horse or dog races (5.6% and 6.2%), and betting on sports (3.3% and 6.2%)

- HILDA found that between 2015 and 2018, regular gambling on Lotto/lottery games, instant scratch tickets, and poker machines/pokies decreased while betting on horse or dog races, betting on sports, keno, casino table games, private betting, and poker increased (AIHW, 2021).

Risk factors in addictions

Research has identified a number of risk factors that contribute to the development of addictions. The focus of research has included genetic predisposition, neural/brain characteristics vulnerability, psychological factors, environmental factors, early age onset of use, and specific populations. An important discussion in the research has been focused on the link between nature (genetics) and nurture (environment). The genetic predisposition argument proposes that a client’s genetic information related to their familiar profile is an important consideration in addictions. Over recent decades research involving intergenerational studies, twin studies, adoption studies, biological research, and the search for genetic markers of addictions have been utilised to further explain addictions vulnerability. While psychological and environmental factors appear to be more influential in determining whether an individual starts to use substances or engages in compulsive behaviour, genetic factors appear to have more of an influence in determining who progresses in the addictions process (CASA Columbia, 2012). Based on these studies, addiction is 50 percent due to genetic predisposition and 50 percent due to poor coping skills. This has been confirmed by numerous studies. One study looked at 861 identical twin pairs and 653 fraternal (non-identical) twin pairs. When one identical twin was addicted to alcohol, the other twin had a high probability of being addicted. The study showed 50-60% of addiction is due to genetic factors (Melemis, 2019). Therefore, psychoeducation on genetics is an important intervention strategy when motivating clients to make an informed decisions about intervention.

The brain

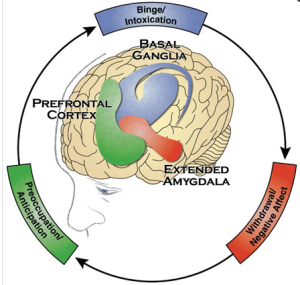

Neurobiological advances in the brain and addictions have been studied for decades. In more recent times, neuroimaging technologies and associated research have shown that certain pleasurable activities, such as gambling, shopping, and sex, can also co-opt the brain. The pleasure principle in the brain has a distinct signature: the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, a cluster of nerve cells lying underneath the cerebral cortex. Dopamine releases in the nucleus accumbens are so consistently tied with pleasure that neuroscientists refer to the region as the brain’s pleasure centre. Dopamine not only contributes to the experience of pleasure, but also plays a role in learning and memory—two key elements in the transition from liking something to becoming addicted to it. Further, in the brain’s process, we find drug reinforcement circuits (reward and stress) that include the extended amygdala (the central nucleus of the amygdala, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and the transition zone in the shell of the nucleus accumbens). A drug- and cue-induced reinstatement (craving) neurocircuit is composed of the prefrontal (anterior cingulate, prelimbic, orbitofrontal) cortex and basolateral amygdala, with a primary role hypothesised for the basolateral amygdala in cue-induced craving (Galanter & Kaskutas, 2008). A drug-seeking (compulsive) circuit is composed of the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), ventral pallidum, thalamus, and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and is important to the craving mechanism. Neuroscience continues to conclude that the brain has demonstrated opportunities for intervention and prevention based on the rewards systems. See Figure 1: The 3 phases of addiction in the brain.

Psychological factors

A cross section of psychological factors (e.g., stress, personality traits such as high impulsivity or sensation seeking, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and other psychiatric disorders) have been researched. The presence of these factors increases the risk that people will develop addictions (Schore, 2003). Individuals actively avoid experiencing adverse states and addictive behaviours continue to alleviate these states despite harmful effects (Jacobs, 1996). In other words, people use chemicals and compulsive behaviours to avoid painful feelings and regulate their distress.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors include exposure to physical, sexual, or emotional abuse and or trauma, substance use or addiction in the family or among peers, access to an addictive substance, and exposure to popular culture references that encourage substance use. We are seeing more young people engaging in technology to avoid loneliness and to connect which are basic human needs. Adverse childhood experiences or childhood trauma have been linked to an increased risk of developing a variety of addictive disorders including addictions to alcohol, gambling, video games, shopping, and sex (Thege et al., 2017).

At risk populations

Children living in families with addictions are another risk group. Children raised in chemically dependent families have different life experiences than children raised in non-chemically dependent families. Children raised in other types of dysfunctional families may have similar developmental losses and stressors, as do children raised in chemically dependent families. There is strong, scientific evidence that alcoholism/addictions tend to run in families. Children of alcoholics are, therefore, more at risk for alcoholism and other drug abuse than children of non-alcoholics. Based on clinical observations and research, a relationship between parental alcoholism and child abuse is indicated in a large proportion of child abuse cases. Children of alcoholics experience poorer physical and psychological health (and therefore higher hospital admission rates), poor educational achievement, eating disorders and addictions problems, many of which persist into adulthood (NACOA, 2020).

Families at risk

Intervention issues with families and addictions commenced alongside the foundation of Alcoholics Anonymous in 1935. From the late 1960s and early 1970s, researchers began to consider the influence that the family systems of individuals with addictions problems had on alcohol and substance use. Specifically, family studies began to investigate and identify the ‘functions’ that alcohol and other substances serve in different types of families (McCrady et al., 2012). Family systems have the potential to enable addictions and compulsive behaviour. This is because family members tend to react to substance use and compulsive behaviour according to their particular patterns. These patterns have a tendency of perpetuating the use of other drugs and behaviours (Crnkovic & Del Campo, 1998). Parents may have addictions themselves; siblings may have addictions problems; family values and attitudes as well as practices may influence problems, family dynamics and relational problems; and genetic and biological factors impact the individuals (Waldron & Slesnick, 1998). The contemporary view of addictions and families takes into consideration cultural differences and how these impact family roles, dynamics, communication, priorities, support structures and so on (McCrady et al., 2012).

Women at risk

Researchers have identified risk factors for women that differ from men. The National Institute of Health and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2008), for example, have compiled a summary of research in the area of women and have developed specific interventions that address women’s needs such as stress, childhood abuse, victim of sexual violence, trauma, and pregnancy. Women who are in partnership with addicts also need interventions that focus on the area of co-dependency.

Adolescents at risk

Adolescents are another risk group to consider when working in the field of addictions. They are influenced by socialisation and cultural environment factors. As part of their developmental process adolescents can be influenced toward chemical and behavioural addictions. New technology and lifestyle, peer group practices (peer pressure), wanting to be accepted and approved, experimentation, and risk-taking behaviours, are all part of the picture counsellors will be faced with when working with this population. The AIHW (2022) found the smoking and drinking patterns of Australia’s teenagers have shown some positive signs in recent years; many young people are deciding not to smoke or drink in the first place, while others are older when they first try. Illicit drug use has also fallen among Australian teenagers—those aged 14–19 were less likely to use illicit drugs in 2019 (31%) than in 2001 (37%). Cannabis use changed over the same period (21% in 2001 to 8.2% in 2019), use of ecstasy and cocaine increased from 8% and 5.1% in 2011 to 10.8% and 10.8% in 2019, while use of meth/amphetamines decreased from 13.2% in 2001 to 2.3% in 2019. However, there remain developmental risks for this group.

Older adults at risk

Older adults are vulnerable to addictions. Research identified that issues of getting older, retirement, loss of a partner, and medical conditions, all affect older adults. The use of chemicals and addictive behaviours help to relieve emotional distress (Satre, 2010).

LGBTQI+ at risk

The abbreviation LGBTQI+, often used to refer to people of diverse sex, gender, and sexual orientation, stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, plus. However, the limitations of this term when trying to describe the full extent of people’s gender diversity, relationships, sexualities and lived experiences should be acknowledged. This group is vulnerable to addictions and counsellors need to be able to work with this highly vulnerable group. As the 2016 National Drug Strategy Household Survey found, adults who identified as homosexual or bisexual or not sure/other sexual orientation, reported higher levels of psychological distress than heterosexual adults. Evidence from small-scale LGBTQI+ targeted studies, and some larger population-based surveys, indicate that LGBTQI+ people face disparities in terms of their mental health, sexual health, and rates of substance use (ABS, 2008). It has been suggested that many LGBTQI+ people use these substances to cope with the discrimination and difficulties that LGBTQI+ people regularly experience, that there may be a normalisation of substance use in some LGBTQI+ social settings, and that people who identify as being homosexual or bisexual are generally more accepting of regular adult use of drugs than people who are heterosexual (Leonard et al., 2015). This has major implications for intervention strategies with this population and needs to be considered in the at-risk group profile.

Social inequality in at risk groups

Social inequality is a strong predictor of addictions, especially related to lower social class (Room, 2005). This includes race/ethnicity factors in the literature. Culture impacts alcohol and substance use and misuse in many ways: what are considered ‘norms’ relating to alcohol and substance use; what substances are considered normal and abnormal, legal and illicit, acceptable and not acceptable; and represents an important factor in intervention and intervention planning. Culture also plays a central role in forming the expectations of individuals about warnings and problems faced with drug use. For example, Indigenous Australians constitute 2.6% of Australia’s population. However, they experience health and social problems resulting from alcohol use at a rate disproportionate to non-Indigenous Australians. Indigenous Australians suffer from dispossession, the stolen generation, intergenerational trauma, poor health status, high levels of incarceration, and diversion of income which create social inequalities. Primary interventions have had challenges for this population to recover over the decades. There were also no significant changes in drug use among Indigenous Australians between 2013 and 2016 but changes are difficult to detect among Indigenous people in the NDSHS due to the small Indigenous sample (AIHW, 2017).

Pharmacology and psychoactive substances

An understanding of the various substances in society and their categories is important for counsellors. There are two areas to consider with the action of psychoactive substances: depressants and stimulants, and the effects on the central nervous system (CNS). Depressant drugs begin their action in the cerebral cortex and work their way down to the midbrain. This action is an inhibitor and sends a cascade of effects to the body and brain. These include disinhibition, impaired judgment, emotional liability, loss of motor control skills, and in extreme cases poisoning. The classification of these psychoactive drugs includes alcohol/ethanol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, GHB, (Club Drug), and opiates. (See Commonly abused drugs charts for names, physical, psychological, possible effects, overdose effects, and withdrawal syndrome.) Additionally, pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence, including anti-craving medications for relapse prevention, is important for counsellors to understand. (See Pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence: Anticraving medications for relapse prevention for further details.)

Major theories of addictions

The four factors of physiological, psychological, sociological, and neurobiological, support the theoretical understanding of addictions. Emerging trends for treatments that match these 4 factors will be offered alongside intervention application for all four.

Physiology

Physiology involves the effects of chemicals and compulsive behaviours on the body and mind. Drugs are chemicals that affect both body and brain. Changes in the brain mechanisms have been researched and are complex because we must consider short term use, long term use, a variety of drugs, consumption, and age of onset. All these conditions need to be considered when assessing a client with an addictions issue. Research by Licata and Renshaw (2010) demonstrated that drug abuse affects neuronal health, energy, metabolism, maintenance, inflammatory processes, cell membrane turnover, and neurotransmission. What is important to remember is that the brain has been the recipient of psychoactive substances and the compulsive behaviours in addictions allow individuals to cope with internal and external stressors. However, substances have been used for a variety of other reasons including pain relief, pleasure, mystic insight and spirituality, escape, to relax, and stimulation.

Substance use issues have been segregated from the rest of health care and, as a result, are treated very differently from other chronic conditions such as anxiety or depression. However, we know that substances cross the blood-brain barrier and cause changes in the brain. Biological markers of disease states, therefore, need to be considered. In the disease/condition model, there is an organ, the midbrain; the defect is the cause of addictions (e.g., genetics, trauma, mental health issues, stress); and then there are the indicators such as loss of control, “bad behavior”, criminality, and so forth (McCauley, 2015). From a physiological perspective, addiction to alcohol and other drugs (and associated compulsive/pathological behaviour) is considered a brain disease whereby drug actions on brain circuitry result in changes in the control of behaviour (Tomberg, 2010).

Intervention approaches in physiology are detoxification, harm reduction, mindfulness-based stress reduction, mindfulness without meditation. These models reduce the effects of the chemicals in the body and reduce emotional dysregulation in the brain. Detoxification from alcohol/drugs is the removal of substances clients have become dependent on and withdrawal symptoms are medically monitored within a medical setting. Harm-reduction model is used for clients who are moderate in their use and wish to cut down on their use to avoid becoming dependent on substances. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is a combination of cognitive behavioural techniques and mindfulness strategies (such as meditation, breathing exercises, and stretches) that are designed to help individuals better regulate their emotions and conflicting thinking. As a result, clients learn how to manage and relieve feelings of distress without reliance on substances.

Psychology

As we explore the psychology of addictions, we need to consider several aspects. One characteristic is mental health disorders which are generated by drug use and addictions. The other characteristic is that people use drugs to emotionally regulate themselves. This term for this dynamic used to be labelled dual-diagnosis and now called it is known as comorbidity. Chronic use of some drugs can lead to both short- and long-term changes in the brain which can lead to mental health issues including paranoia, depression, anxiety, aggression, hallucinations, and other problems. Many people who are addicted to drugs are also diagnosed with other mental disorders and vice versa. Alcohol and drug abuse can also increase the underlying risk for mental disorders. Mental disorders are caused by a complex interplay of genetics, the environment, and other outside factors. If you are at risk for a mental disorder, drug or alcohol abuse may transform the underlying risk for a mental health issue. Multiple national population surveys have found that about half of those who experience a mental illness during their lives will also experience a substance use disorder (Ross & Peselow, 2012). Data show high rates of comorbid substance use disorders and anxiety disorders—which include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Magidson et al., 2012). Substance use may also sharply increase symptoms of mental illness or trigger new symptoms. Alcohol and drug abuse also interact with medications such as antidepressants, anti-anxiety pills, and mood stabilizers, making them less effective.

Trauma and addictions are other considerations for counsellors. Trauma can lead people to use chemicals or compulsive behaviours to seek pleasure or self-medicate with alcohol or other drugs, food, sex spending, gambling, and the internet. People who have had subjective experiences of trauma, not feeling safe, adversity, and fear in their childhood and in their family may also have parents with addictions and mental illness disorders. This complex combination is unpredictable and uncontrollable and can cause psychological damage. These symptoms are encoded in their memory and genes are expressed to avoid pain and seek pleasure. A person who is abused or traumatised may develop dysfunctional defences strategies or schemas designed to ward off emotional and psychological pain (Dayton, 2000).

Intervention approaches in psychological issues can include many models. Current examples that are evidence-based are motivational interviewing (MI), mindfulness and addiction therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT). ACT addresses clients’ goals and values to guide the process of behaviour change and increase psychological flexibility (Hayes et al., 2012). CBT is a treatment approach for a range of mental and emotional health issues including anxiety, depression, and substance misuse. CBT aims to help a person identify and challenge unhelpful thoughts and to learn practical self-help strategies. These strategies are designed to bring about positive and immediate changes in the person’s quality of life.

Sociological theory

Social theory explores how the social harm of addictions reaches across several areas within the social context. In social learning theory, people who experience fragile social bonds tend to deal with those situations by using drugs and engaging in compulsive behaviour to deal with their discomfort and isolation. Role modelling is an associated factor to consider in the social frame of family structures. Children who live in a family with addictions have role models and witness strategies to reduce stress by using drugs (NACOA, 2020). This action, called social reinforcement, plus genetics, have an influence on how children make choices when feeling socially isolated or distressed. As a result, stress and coping become learned neural pathways that are habitual. Most of these children and then adults have poor coping skills and an inability to deal with stressors and are at high risk of addiction and compulsive behaviours and activities (Miller & Carroll, 2006). The social theory model also considers where addictions are highest, such as in clusters in a city or town, alongside poverty, where there is a decline in labour and skilled jobs, increased lack of housing, and living costs rise, and where there is child abuse or neglect.

Social models for intervention focus on the counsellor’s need to consider support groups and group psychotherapy to help clients learn how to reconnect with themselves and others. These models help clients to learn how to reconnect and establish healthy relationships as well as tools to maintain their recovery. Three support groups are the 12 step programs (AA, NA, and so on), SMART recovery, and group psychotherapy.

12 Step program is a community support group where recovering clients can find hope. It works by connecting people and providing support. It is worldwide and has some good results for outcomes in abstinence and recovery. It can be a lifetime process. Sack asserts in his article, Mapping AA: The Neuroscience of Addiction (2014), that not only does chronic substance abuse rewire the neural pathways, but that 12-step recovery can be of great help by providing prosocial connection and repairing faulty wiring that chronic substance abuse has caused.

Research for positive outcomes can be found with Project MATCH (Matching Alcoholism Treatment to Client Heterogeneity): rationale and methods for a multisite clinical trial matching patients to alcoholism intervention found 12 Step groups, Motivational Interviewing, and then Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, to be the most effective intervention outcomes for alcohol/addiction (NIAAA, 2020).

Group psychotherapy, most often found with in-patient treatment, residential programs, and outpatient programs, allows clients to feel that are not alone with many of the issues that they are experiencing. DrugAbuse.com (2020) identifies five types of groups for psychotherapy:

- psychoeducational groups which offer general education and information on a range of issues related to addictions

- skill development groups which offer specific strategies for handling triggers, communication and parenting, anger responses, and managing finances

- cognitive behavioural therapy groups for changing thinking and behavioural patterns, as well as relapse prevention

- support groups offer care and support between the group leader and group members as well as between group members

- interpersonal process groups focus on emotional development and childhood concerns which impact on decision-making, impulsivity, and coping skills.

These groups combine to provide education and strategies on the recovery process, support, problem-solving, feedback from others, and healthy skills in developing relationships (DrugAbuse.com, 2020).

Neuroscience

The neuroscience theory has been a paradigm shift in psychotherapy over the past two decades. The breakthroughs in neuroscience have given us neural underpinnings for behaviour, validating affectively focused practice (Dahlitz, 2015). Grawe grounded neuropsychotherapy in a model of mental functioning he termed the consistency-theoretical model (Grawe, 2007). This model identifies the psychological needs being served by schemas. In addictions, clients form a schema of their needs, neural networks are then encoded in childhood in their genome or epigenetic expressions of genes and learning (memory formation). These memories are implicit or unconscious and they lie at the base of approach/avoidance motivational schemas. This constitutes a primary target for therapeutic change. It is therefore pertinent to understand something of how memory is formed on a neural level and what conditions counsellors might be necessary for change (Dahlitz, 2015). In working with clients with addictions, counsellors need to beware that a client is operating from these memories and has no awareness of them. These memories also inform how clients anticipate their future. The motivation for addictions then is a driving force to avoid pain and seek pleasure. Knowing what drives or motivates people to distract themselves helps to increase their awareness and decrease shame as they develop new learning through neuroplasticity. Substance-related and compulsive behaviour is therefore a disorder of regulation.

Motivational interviewing (MI) is another intervention approach that works with neuroscience. Motivational interviewing has been researched for over 30 years for its effectiveness in addictions intervention (Miller & Rose, 2009). The work of Prochaska and DiClemente (1983) lay the foundations for MI with the change model. MI explores motivation and change from a relational perspective rather than from a rational decision-making process. MI allows for a recognition of normal ambivalence with clients who have a strongly developed defence mechanism, low levels of trust, and a low motivation to change due to implicit learning (hijacked brain).

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), developed by Steven C. Hayes and colleagues, is an overarching approach which incorporates a range of therapeutic approaches, including DBT, CBT, and MBCT. The aim of ACT is to accept private events, such as unwanted thoughts, feelings, memories, images, or bodily sensations, rather than change them. In this way, there is an increase in commitment to the change the client chooses. Additionally, ACT addresses clients’ goals and values to guide the process of behaviour change and increase psychological flexibility (Hayes et al., 2012).

Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) is another model that works with neuroscience. DBT incorporates concepts that work with addictions and modalities are designed to promote abstinence and to reduce the length of adverse impact on relapse. Several randomized clinical trials have found that DBT decreased substance abuse in clients with borderline personality disorder. The intervention may also be helpful for clients who have other severe disorders co-occurring with addictions or who have not responded to other evidence-based addictions therapies (Dimeff & Linehan, 2008). For substance-dependent individuals, substance use is the highest order DBT targets within the category of behaviours that interfere with the quality of life.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is another model that can fit with neuroscience. CBT is a classification of mental health counselling founded in the 1960s by Dr. Aaron T. Beck. Cognitive behavioural therapy is used widely today in addictions intervention. CBT teaches recovering addicts to find connections between their thoughts, feelings, and actions and increases awareness of how these things impact recovery. CBT identifies negative “automatic” thoughts. These thoughts are implicit, in memory, and not conscious. These thoughts are impulsive and come from an encoded misconception of reality formatted in childhood in the face of un-nurturing caregivers. They come with loaded emotions and reactions with defences that are in the brain pathways.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is another model that can be applied to neuroscience. MBCT is a combination of cognitive behavioural techniques and mindfulness strategies (such as meditation, breathing exercises, and stretches) that is designed to help individuals better understand their emotions and thoughts (www.themindfulword.org). As a result, clients learn how to manage and relieve feelings of distress and lowers cortisol in the brain to reduce stress, which allows for neuroplasticity (Dahlitz, 2015).

Component model of addiction argues that addictions can be both substances and behavioural and have different expressions, yet there is a common underlying disorder and mechanisms which need to be addressed in intervention. So, the component model (also known as the transdiagnostic treatment model) of addictions targets underlying similarities between behavioural and substance use addictions (Hyoun & Hodgins, 2018). All addictive disorders have common vulnerabilities that all have psychological, cognitive, and neurobiological characteristics. This more current approach explores behaviours such as gambling, including internet gambling, which are compulsive behaviours and found in the DSM 5-TR (2022). Common to all substance use and addictions are the underlying disorders of compulsivity. Interventions aim to address those vulnerabilities such as negative urgency, deficits in self-control, expectancies and motives, deficits in social support, and compulsivity, and maladaptive preservation behaviour. Interventions with this model involve a number of approaches which have empirical support for their efficacy (Sauer-Zavala et al., 2017).

Interventions within the component model include CBT models which are transdiagnostic as they address the present conditions while targeting underlying vulnerabilities. They also include mindfulness-based interventions and ACT which are all based on a transdiagnostic model. ACT research is at the forefront of process research, with initial data supporting the ACT model (for a meta-analysis, see Levin et al., 2012).

Attachment theory and addiction

Attachment theory recognises that human beings are interactional and constantly impacted by our relationships and the environment. When the fundamental ability to connect with others is damaged, as in families with addictions or trauma, it is not surprising that some clients seek emotional support and regulation through substances and compulsive behaviour. As the use of substances increase, the individual is further impaired, and the cycle of addictions is set in motion (Fletcher et al., 2015). Attachment theory highlights the connection between the social, psychological, and biological. Emotions, thoughts, and a sense of self emerge from neural structures and processes that occur within the social environment and impact the psychological and biological aspects of the client (Schore, 2014).

Interventions with attachment theory involves what Oliver Morgan calls “Counselling for Connection” (2019). This model, as mentioned in the introduction of this chapter, focuses on affect regulation and emotional integration through appropriate attachment between the client and counsellor. Attachment-sensitive counselling encourages a welcoming empathic relationship therapy healing and repair. Connection with another self becomes healing and “growth-facilitating” (Schore & Schore, 2008. p. 13). As stated earlier, this is a person-to-person healing process. The goal of this model is to heal wounded attachments that have created current difficulties. The counsellor needs to be attuned to the client’s needs through compassion, empathy, and non-judgmental relating. It is a co-creating process as the more secure interaction allows for the application of corrective (reparative) relational experiences in a new safe environment (Morgan, 2019). Attachment-sensitive therapy develops a therapeutic alliance/relationship and the capacity for compassion and acceptance.

All of these models mentioned work with neuroscience and can also overlay to other models as described in this section. Models can be very flexible in working with substance use, addictions, and compulsive behaviours. This all depends on where the client is at and what their goals are. In the next section counselling with an issue of addictions, we will explain further how this all works by applying screening techniques, assessment, referrals process and self-care linking to the models.

Counselling with addictions

Counsellors need to be emotionally attuned caregivers providing a growth-enhanced environment and exploring clients’ motivation and their resources (Gassmann & Grawe, 2006). Counsellors need to create a positive environment for change because people are naturally inclined toward positive growth and have a great capacity for self-understanding and modifying their behaviour and attitudes, given the right environment, climate, and support (Gassmann & Grawe, 2006). Research has shown that positive social interactions promote both safety and new neural patterns. This can result in enhanced attachment and control, and stress reduction (Alison & Rossouw, 2013).

Assessment can be seen as the exploration of the nature and potential causes of a client’s issues (Lewis et al., 2011). The assessment considers a holistic approach. Counsellors need a curiosity-oriented approach. While not a therapy in itself, it is a state of being that shifts the mind, alters the flow of energy and information within the brain, and changes biology all the way down to gene expression and protein synthesis to produce the biochemical milieu. These changes create the best conditions for therapeutic progress toward beneficial change (Hill, 2020). There is an energy flow between both therapist and client. These “mirror neurons” show how we are wired with each other (Siegel, 2001). Neuroscientists tell us that the therapeutic co-regulation occurs, says Schore and Schore, through a “relational unconscious” in which “one unconscious mind communicates with another unconscious mind” (2008).

Assessment of this unique population must consider neurobiological, psychological, and learning defences. Here are a few considerations to ponder.

- Neurobiological approach: People who engage in substance and behavioural addictions need an integrative approach to assessment. Many of the behaviours that users display can be impulsive, compulsive, and sometimes aberrant, some argue that substance use is not tied to neurobiology but is a behaviour of choice (McCauley, 2015). This argument negates what happens in the brain’s reward system and scientific evidence.

- Why do they come? Many clients come to therapy because they are forced and are, therefore, involuntary. Some enter interventions due to health problems, others because they are referred or mandated by the legal system, employers, or a family member (Milgram & Rubin, 1992). Initially, counsellors need to determine the client’s readiness for change (Australian Government Department of Health, 2020). Without this important information nothing you offer the client will work and they will not take ownership of their recovery process. Motivational Interviewing captures all the positive ideals of being with the client in a cooperative manner, allowing for a psychological connection and dialogue to develop between the therapist and client.

- Barriers: Learned defences need to be considered first in order to achieve a positive outcome in the assessment process. Assessment can for any client be overwhelming, so careful consideration of that factor alone is needed here. The traditional way was to confront the client’s “denial” to get results and we found that did not work. We need to hold the diagnosis and first connect with the client. We know from neuroscience, that the relationship/connection is the key element for the best possible outcome in psychotherapy (Dahlitz, 2015).

- Stigma/shame: Stigma has the potential to negatively affect a person’s self-esteem, damage relationships with loved ones, and prevent those suffering from addictions from accessing interventions (Room, 2005). Social stigma is a perception that these individuals and their families are deviant, a moral approach. As shame is a major barrier to engagement, Flanagan developed an account of addictions which includes shame as part of the addictions phenomenon (Flanagan, 2013). Counsellors must also assess their own stigmatisation attitudes toward people with addictions (Myers & Salt, 2007).

The next step in the assessment process is to consider what level a substance user is at—mild, moderate, or severe—all these issues need to be considered in a comprehensive assessment. The proposed interventions also need to be integrative in their approach. Behavioural addictions were not found in the DSM so the component model discussed earlier will be utilised in this chapter to address behaviour assessment.

Mild users (previously called experimental user) use the drug with no significant ill effects and with no marked withdrawal or tolerance. This person can use alcohol and drugs and return to their normal life. The practice can be precarious, however, because even early, voluntary use can interact with environmental and genetic factors and result in addictions in some people, yet not in others. The concept of behavioural addictions is still controversial. While some people exhibit manageable behavioural self-regulation—even in so-called behavioural addictions like over-eating, pathological gambling, and video gaming—others with these disorders often manifest compulsive behaviours with impaired self-regulation (Volkow et al., 2016). Addictions used to be considered a continuum of use, or stages of use, but the theory no longer has much value because not everyone who uses experimentally becomes an addict.

Moderate users may not consider what is happening in their brains, so psychoeducation needs to be utilised to increase their awareness. When use is increased and the reward system is activated, users may pursue that reward with some negative effects. There may be some ambivalence in their thinking that they can use like others and that there is no problem; stigma and shame may also be present. This is a fine edge for clients and for intervention providers in helping clients to participate in interventions. Harm reduction approaches can be very effective for them.

Severe users are characterised by an increase in a psychological need to use. Tolerance develops in that they need more of the drug to get the same high or reward. In a person with addictions, the reward and motivational systems become reoriented through conditioning to focus on the more potent release of dopamine produced by the drug and its cues. As a result, with severe use, the person no longer experiences that same degree of euphoria (tolerance). In addition to resetting the brain’s reward system, repeated exposure to the dopamine-enhancing effects of most drugs leads to adaptations in the circuitry of the extended amygdala in the basal forebrain; these adaptations result in increases in a person’s reactivity to stress and lead to the emergence of negative emotions (Davis et al., 2010; Jennings et al., 2013).

Screening

Again, it is important to note that the best indicator of which level your client is at (and it is not linear) is your connection with the client. Instruments are best used after you have established rapport with your client, otherwise as said earlier, they will become defensive and shut down. Remember that diagnosis limits vision and it diminishes the ability to relate to your client (Yalom, 2002). Connection and rapport are key in the first phase of the interview; with that said we also can learn much from psychometric instruments and so can the client. There are at least 100 instruments that can be used that have shown good reliability in the research. They are also designed to fit different chemicals of addictions and that can be a challenge if your client presents with multiple chemicals and behaviours. Screening is useful to determine the intervention needs of the client.

Referrals

Given that many clients in drug and alcohol counselling are involuntary, referral to an advocate (legal or otherwise) may be required at times to independently safeguard their interests. This is a recommendation of the AASW Code of Ethics (2010). As substance-using clients present with many co-occurring conditions and life difficulties, other services are highly likely to be needed. Therefore, gaining written client consent for making referrals, writing referral letters and reports, is essential. It is also essential when referring clients to services to explain the reason for making the referral and the benefits for them, and the role that the service will play in their lives (Rubin, 2012).

Self-care

Burnout is an occupational hazard in our work as counsellors. Working with clients who present with addictions can be most challenging due to their defences that involve neural networks, shame, and stigma. Burnout can be disabling but if recognised early can be rectified quickly. Counsellors are impacted by emotional trauma, and they are often witnesses to horrific stories of distress and pain. Counsellors need to develop personal boundaries and be mindful of transference (the phenomenon whereby we unconsciously transfer feelings and attitudes from a person or situation in the past to a person or situation in the present) and countertransference (the response that is elicited in the counsellor by the client’s unconscious transference communications. Countertransference response includes both feelings and associated thoughts). The first step is to be aware of the indicators. Because counsellors are in a therapeutic relationship with many clients who have poor social skills and histories of difficult relationships, these clients may project feelings about someone else, particularly someone encountered in childhood, onto the counsellor. Counsellors may have a reaction to these issues and take such experiences personally, especially when the counsellor has diffuse boundaries. As a result, there will be a rupture in the relationship.

Counsellors can protect themselves by getting out of the isolated bubble and seek support through supervision or co-counselling with other counsellors. Personal counselling on issues that may surface while working with clients is suggested. Recharging is also important such as taking time to exercise, eating healthy food, developing hobbies, and utilising meditation and relaxation techniques which can assist. All strategies you offer your clients when they are distressed can be useful for you as a counsellor. Combating burnout can include not having high expectations of yourself and your client and knowing it is natural to experience burnout and require support.

Key intervention with component model of addiction/transdiagnostic model of behavioural and substance addictions

A key intervention with the component/transdiagnostic models addresses the underlying mechanisms that are common to both substances and behaviours (Hyoun & Hodgins, 2018). Intervention with this model encompasses a number of approaches which have empirical support for their efficacy (Sauer-Zavala et al., 2017). In considering which model to apply the counsellor needs to consider common underlying conditions: negative urgency, deficits in self-control, expectancies and motives, deficits in social support and compulsivity, maladaptive preservation behaviour. For example, addressing expectancies and motives by applying CBT elements. Cognitive expectancies for the effects of addictive behaviours have been found to be an aetiology and maintaining factor of addictive disorders (Mudry et al., 2014). There are two types of thoughts that maintain dysfunctional beliefs: permissive beliefs and anticipatory beliefs. Interventions might include disputing beliefs that justify substance use or compulsive behaviour and what addictive behaviours do for them. These beliefs may maintain and/or exacerbate engagement in the addictions. In relation to addictions, three motivations have been identified: 1. enhancement motivations (i.e., engaging in addictive behaviours to enhance excitement and positive affect); 2. social motives (i.e., engaging in addictive behaviours for social benefit) or basic human need to connect; and 3. coping motives (i.e., engaging in addictive behaviours to alleviate negative affect). These three motives are linked to neurobiology and can be addressed in neuropsychotherapy by utilising motivational interviewing to develop awareness and coping skills. Relapse prevention as an intervention for ongoing recovery also needs to be considered. This is an important issue and requires counsellors to address relapse with their clients in the early stages of intervention. There is evidence that approximately two-thirds of clients who complete intervention for addictions relapse within the first 90 days. The frequency of return to drinking is estimated to be between 70 and 74% within the first year. More current studies show that the relapse rate for substance use disorders is estimated to be between 40% and 60% (American Statistics/Drug & Substance Abuse Statistics, 2019).

Remember post-acute withdrawal (PAW) symptoms are not easy to observe as they are sub-clinical, long term (about 12-18 months), and cause dysfunction in recovery. Clients have difficulties with thinking clearly, managing their emotions, remembering things, sleeping restfully, physical coordination, and managing stress. All of these symptoms of PAW can be addressed in treatment with counsellors in outpatient or individual therapy. In therapy, high risk situations need to be addressed. These are any experiences that can activate the urge to use alcohol or other drugs or compulsive behaviour in spite of the commitment not to. Counsellors can assist clients to manage high-risk situations by identifying the high-risk situations and developing strategies for managing them. CBT can be utilised to log experiences of high-risk situations by identifying the specific situations that can happen, and giving the situations a title, name, or a phrase to help the client remember their commitment (Gorski, 2007).

Case study George: Assessment

George was interviewed and assessed using the 5 P’s for case conceptualisation (Macneil et al., 2012).

- Presenting problem: Drinks 5 times a week and 6-10 beers on weekends, over the alcohol limit for males, marriage breaking up due to drinking, and work problems due to alcohol leading to missed days and poor performance at work.

- Predisposing factors: Family history of alcoholism and parental neglect due to mother’s depression. He felt shame and stigma because of her depression. Father was distant and emotionally demanding. In his adulthood, he has had intimacy problems with his wife and has a conflictual relationship with her.

- Precipitating factors: Isolation at school and poor performance due to learning disability. Drinking to avoid painful emotions interfering with marriage. Isolation due to symptoms of depression.

- Perpetuating factors: Ambivalence to change due to fears. Shame about his sex addiction. Fear of being depressed like his mother and an alcoholic like his father. Isolation loss of contact with family and friends. Restless and bored.

- Protective factors: George is motivated to change. Realises that an alcohol lifestyle goes against his values. Has attempted to stop before and he loves his wife.

The psychosocial assessment with George showed that: he was having problems in his marriage due to alcohol use; had symptoms of depression from his depression, anxiety, stress scales (DASS) score; and the Attachment Scale Test results showed a preponderance to dismissive-avoidant attachment style because he tends to keep an emotional distance between his wife and has poor connections with others at work. He has a history in his family of alcoholism and his parents were not emotionally available to him. Addiction adaption to early adversity. He has had physiological problems due to his drinking, and an enlarged liver. He feels disconnected from the world and his drinking helps to protect himself from pain.

George was given several screening tests. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and his total score was 25 points (i.e., addiction likely). He took the Cut-Annoyed-Guilty-Eye (CAGE) screening test and answered 2 questions positive for alcohol problems. He undertook the Gambling Addiction test and scored high for gambling addiction. He also disclosed the compulsive use of pornography and was given the Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST) and scored high on the test.

On the basis of this assessment, counsellors can develop appropriate strategies to assist George.

Case study George: Intervention plan

The conclusions for George are severe on the DSM 5-TR screening for alcohol use, high score on the AUDIT (17) and gambling and sex addiction tests. George has multiple addictions and interventions will focus on these issues. Because of George’s ambivalence and fear, and his high level of dangerous drinking, he will be detoxed first in an in-patient hospital setting and transition to the in-patient program to work with his addictions in a safe environment. He will be given medication for craving management and for his depression symptoms.

Intervention strategies are medical management, withdrawal management, and post-withdrawal management. George will first work with his therapist utilising motivational interviewing to access his motivation for treatment. He will attend group psychotherapy daily to work on his family-of-origin issues. One-to-one weekly therapy will focus on developing an ongoing intervention plan and monitoring medication and intervention targets. In his therapy sessions, he will work with his common vulnerabilities and develop strategies to overcome the vulnerabilities utilising CBT and ACT strategies. He will develop skills in recovery utilising the DBT workbook in the group process. Family/couple therapy will be part of his intervention plan. He will complete in-patient treatment and then be transitioned to outpatient to continue his craving management and attend 12 Step support groups for ongoing continuing care. His goals are to become alcohol-free in 3 months’ time, manage his cravings, and work on his marriage. He will develop exercise plans to enhance his recovery and develop a healthy diet. Attending AA 12 Step Support groups aim to get an understanding of his addiction and how to remain abstinent from his addictions. This integrative approach will address all his addictions in the intervention settings.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided an overview of approaches to addictions intervention. Addictions intervention is very complex, and in constant flux. Counsellors have to keep up to date with the policy changes in each country as well as the new research in pharmacology, models, current statistics, and new developments in intervention. This chapter reviewed some of the traditional approaches as well as the new 21st century approaches to addictions. The intention was to offer a more user-friendly approach in terms of assessment and diagnosis, utilising an integrative approach. The inclusion of more modern concerns, such as internet addiction, mobile phone addiction, video-gamming, and internet gambling, have been discussed along with common vulnerabilities in addictions. The field of addictions is facing a challenge for counsellors because more people are searching for entertainment and distraction due to our stressful world. Some people are more vulnerable to becoming addicted whilst others may have a problem rather than addiction and still need support. Shame and stigma have been key issues to be dealt with when dealing with our clients.

We, as counsellors, need to be more attuned to ourselves and our clients. Clients with addictions have a natural defence networked in their brains and meeting them face-to-face, human-to-human, right-brain-to-right-brain, leads to better outcomes. When we can accept that moderate to severe use is more than a behavioural disorder or choice and see it from a scientific perspective as a condition of the brain, then the stigma and shame can be reduced. Interventions need to be integrative. This means considering the genetics and family influences for prevention strategies, the damage to the cortex, and the imbalance of the midbrain’s neurochemistry. Addictions is more than a behavioural disorder. It involves behavioural changes and complications, cognitive and emotional changes. Therefore, a comprehensive approach needs to be applied to address relapse and cravings. Utilising the integrative and alternative therapies discussed in this chapter can heal the brain. The good news is recovery is possible!

Learning activities

Learning activity 1: Multidimensional family therapy

Please watch the following YouTube clip presented by Howard Liddle as an introduction to MFT: Multidimensional Family Therapy, An Introduction (1 of 2) (10:15).

- Reflect on the MFT model.

- Reflect on how effective this approach might be for families with addictions.

- What are the limitations of this theory?

- Would you incorporate this approach into your own practice?

Learning activity 2: Family rules

Please watch the following YouTube clip by Judy Saalinger, 3 rules that govern the family system in addiction – LastingRecovery.com, (5:00).

- While watching the video consider what were three common ‘rules’ found in families impacted by the misuse of drugs and alcohol.

- While watching the video consider one of the rules and discuss what is the long-term impact on adult relationships resulting from this rule.

- Observe this particular rule and its impact overall on the family.

Learning activity 3: : The disease theory of addiction

Please watch the following video on addiction (2:24).

- Reflect on some of your thoughts about this model.

Learning activity 4: Australian culture in drinking

Watch the following YouTube clip by DrinkWise Australia – Attitudes to alcohol: Creating cultural change in Australia (3:54).

https://youtu.be/WywLrGzZrok

This video shares thoughts and concerns about the drinking culture in Australia.

- Reflect on how you could apply this understanding in the psychoeducation of your clients.

Learning activity 5: Dr. Kevin McCauley on the periodic table of intoxicants

Please watch this video of Dr. McCauley (3:43).

This video shows a complete list of addictions.

- Reflect on what you learned from this presentation that would be useful in your practice.

Learning activity 6: Using AUDIT

AUDIT screening is the most common form of assessing alcohol use. Please review the AUDIT tool.

- Complete the AUDIT from your own experience.

Learning activity 7: ACT Exercise

Here is a simple acceptance exercise. Use at your own risk. If in doubt seek professional advice. Please take some time and practice this method

- Observe – scan the body for any feelings of tension, pain, etc. Try not to listen to your head telling you what the feelings mean, and just observe the actual physical sensation. What colour, temperature, etc is the feeling?

- Breathe – imagine breathing into and around any uncomfortable feelings. It is normal for the feeling to shift, becoming bigger or smaller; just hang in there. Remember this is not a relaxation exercise, even if some people do end up feeling more relaxed afterwards.

- Allow – come back to the present moment, without pushing the awareness away. Don’t struggle with any thoughts or feelings that come up, but also become aware of the world around you.

Reflect on your experience.

Learning activity 8: Attunement

Please watch this video on Attunement (9:26).

This video addresses attunement for clinicians, as mentioned in this chapter. It provides a wider perspective of the concept.

- Reflect on how you might apply this concept to your practice.

- What part of attunement do you need to practice further in order to feel confident?

Recommended resources

Some selected websites for further information on substance use and addictions

These websites are for counsellors who want to learn more about this field and expand their practice. There are a number of government websites, models, information about substances, and additional factors that impact clients with addictions. These are just a small sample, and it is incumbent on each counsellor to develop their own practice.

- American Psychiatric Association (2022). Alcohol-related disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Text revised version (5th ed.).

- American Psychiatric Association (2022). Cannabis-related disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Text revised edition

- Addictions

- Partnership to end addiction

- Neurobiology of addictions. An integrative review.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- The Institute for Addiction Study.

- Drug and alcohol information on statistics and treatment-recovery research at the Recovery Research Institute

- The American Journal on Addictions.

- Project MATCH Research Group (1997). Matching alcoholism treatment to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes.

Additional resources on addictions in Australia, including health policy and at-risk populations

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

- Commonwealth of Australia (2017). National Drug Strategy 2017-2026. Department of Health and Ageing.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (March 2017) Mental health effects.

- Ministerial Drug and Alcohol Forum (MDAF).

- National Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Peoples Drug Strategy 2014-2019 [PDF].

- National Alcohol and other Drug Workforce Development Strategy 2015-2018 [PDF].

- Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet; Alcohol and other drugs knowledge centre.

- Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of NSW.

- State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services (April 2018). Alcohol and other drugs program guidelines – part 2.

- Young people and addictions.

- The MERIT Program.

Additional resources on screening and treatment options

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

- Motivational interviewing (MI).

- ACT and mindfulness activities worksheets [PDF].

- Mindfulness resources from the Mindsight Institute.

- Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) workbook and a complete description of DBT.

- Cognitive behavioural therapy model.

- Mindfulness-based stress reduction.

- Popular mindfulness-based stress reduction exercises.

- The component model.

- Numerous assessment and screening tools.

- Screening with alcohol – Drinkers Checkup and Alcohol Screening.

- Information on overcoming codependency.

- Information on neuroscience and the science of psychotherapy.

- Depression and other resources from the Black Dog Institute.

- Ellen Langer on the science of being mindlessness and mindfulness.

- Claudia Black on family issues.

Information on substances and support groups

- Illicit use of drugs.

- Cannabis use and psychosis: what is the link and who is at risk?

- Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland.

- World-first medication trial for ice addiction.

- 12 Step support groups on how they work.

- SMART recovery.

- Ayahuasca information.

- Mindfulness.

Glossary of terms

abstinent—not using substances of abuse at any time

acute care—short-term care provided in intensive care units, brief hospital stays, and emergency rooms for those who are severely intoxicated or dangerously ill

addiction—a psychological and physical inability to stop consuming a chemical or being involved in a behaviour causing harm to self and others

CAGE questionnaire—a brief alcoholism screening tool asking subjects about attempts to Cut down on drinking, Annoyance over others’ criticism of the subject’s drinking, Guilt related to drinking, and use of an alcoholic drink as an Eye opener

coerced—legally forced or compelled

combined psychopharmacological intervention—treatment episodes in which a client receives medications both to reduce cravings for substances and to medicate a mental disorder

co-occurring disorders (COD)—refers to co-occurring substance use (abuse or dependence) and mental disorders. Clients said to have COD have one or more mental disorders as well as one or more disorders relating to the use of alcohol and/or other drugs.

deficit—in the context of substance abuse treatment, disability, or inability to function fully

detoxification—a clearing of toxins from the body

downers—slang term for drugs that exert a depressant effect on the central nervous system

ecstasy—slang term for methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), a member of the amphetamine family (for example, speed)

epigenetic—is the study of heritable changes in gene expression (active versus inactive genes) that do not involve changes to the underlying DNA sequence—a change in phenotype without a change in genotype—which in turn affects how cells read the genes