21 Microbiology

The study of microorganisms has a very long history and while ancient peoples may have suspected the existence of invisible “minute creatures” that could cause disease, it wasn’t until the invention of the microscope that their existence was definitively confirmed. The original microbiologists relied on observation in their studies, with Hippocrates observing that diseases could be transmitted by objects such as clothing and that people who recovered from plague could take care of plague victims. Much later and with leprosy and also the spread of plague in Europe, it was recognised that disease could be spread between people and the best way to avoid infection was to avoid contact with infected people – ie isolation and quarantine.

The Ancient Greeks and Romans

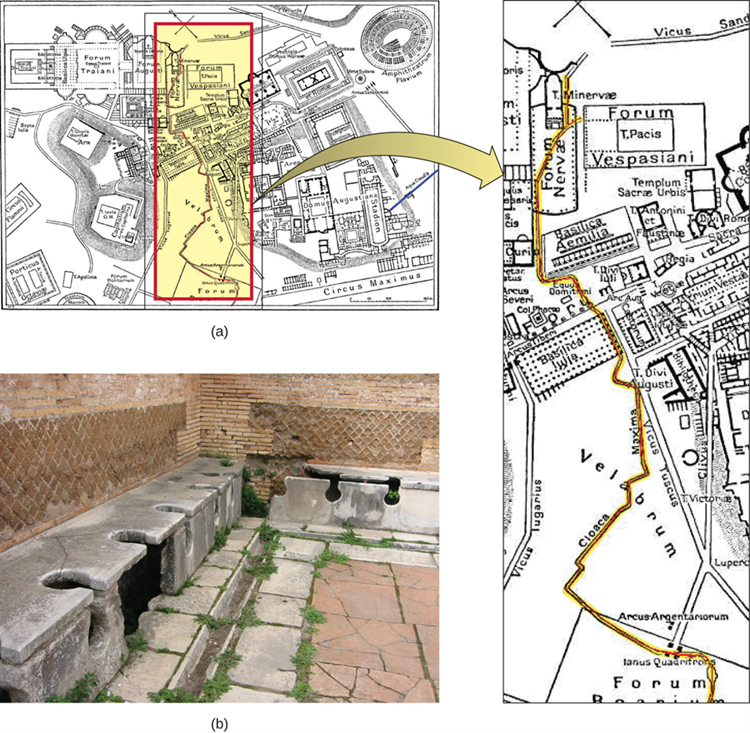

The ancient Greeks attributed disease to bad air, mal’aria, which they called “miasmatic odors.” They developed hygiene practices that built on this idea. The Romans also believed in the miasma hypothesis and created a complex sanitation infrastructure to deal with sewage. In Rome, they built aqueducts, which brought fresh water into the city and a giant sewer, the Cloaca Maxima, which carried waste away and into the river Tiber (Figure 7.1). Some researchers believe that this infrastructure helped protect the Romans from epidemics of waterborne illnesses.

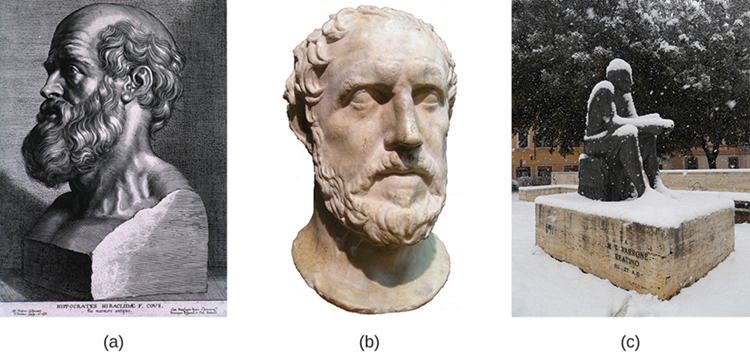

The Greek physician Hippocrates (460–370 BC) is considered the “father of Western medicine” (Figure 7.2). Unlike many of his ancestors and contemporaries, he dismissed the idea that disease was caused by supernatural forces. Instead, he posited that diseases had natural causes from within patients or their environments. Hippocrates and his heirs are believed to have written the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of texts that make up some of the oldest surviving medical books. Hippocrates is also often credited as the author of the Hippocratic Oath, taken by new physicians to pledge their dedication to diagnosing and treating patients without causing harm.

While Hippocrates is considered the father of Western medicine, the Greek philosopher and historian Thucydides (460–395 BC) is considered the father of scientific history because he advocated for evidence-based analysis of cause-and-effect reasoning (Figure 7.2). Among his most important contributions are his observations regarding the Athenian plague that killed one-third of the population of Athens between 430 and 410 BC. Having survived the epidemic himself, Thucydides made the important observation that survivors did not get re-infected with the disease, even when taking care of actively sick people. This observation shows an early understanding of the concept of immunity.

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC) was a prolific Roman writer who was one of the first people to propose the concept that things we cannot see (what we now call microorganisms) can cause disease (Figure 7.2). In Res Rusticae (On Farming), published in 36 BC, he said that “precautions must also be taken in neighbourhood swamps because certain minute creatures [animalia minuta] grow there which cannot be seen by the eye, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases.”

Produced wastewater from a community of people.