1 Directional Terms

In this section

Content in this section includes:

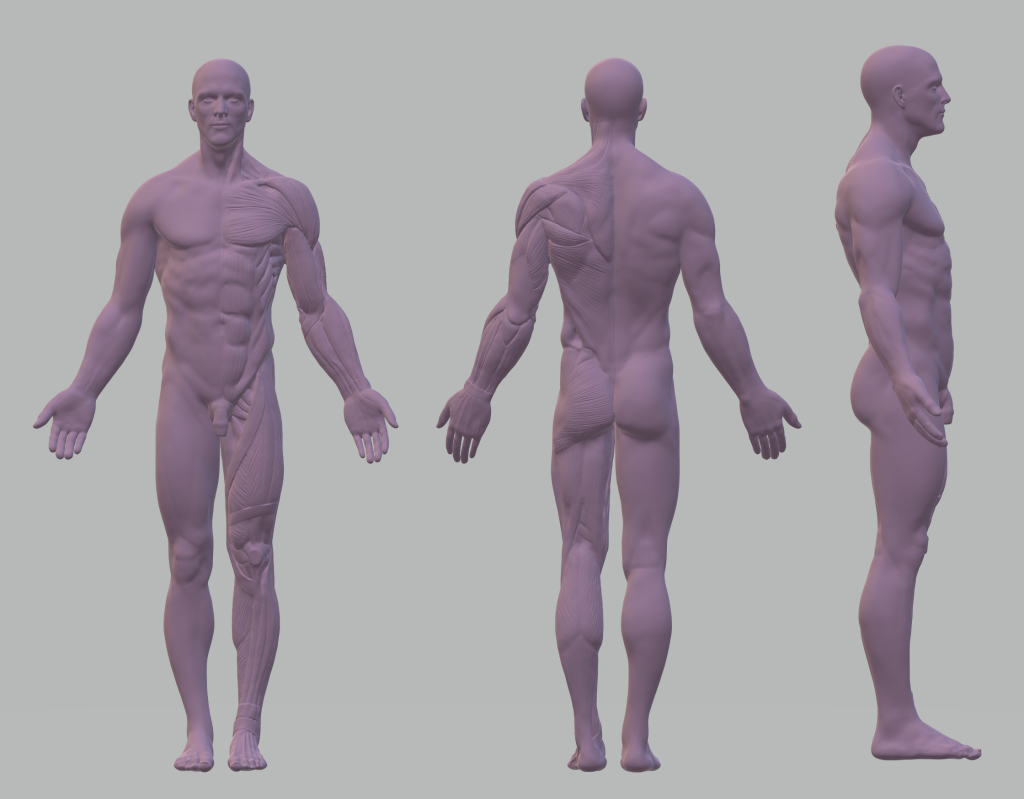

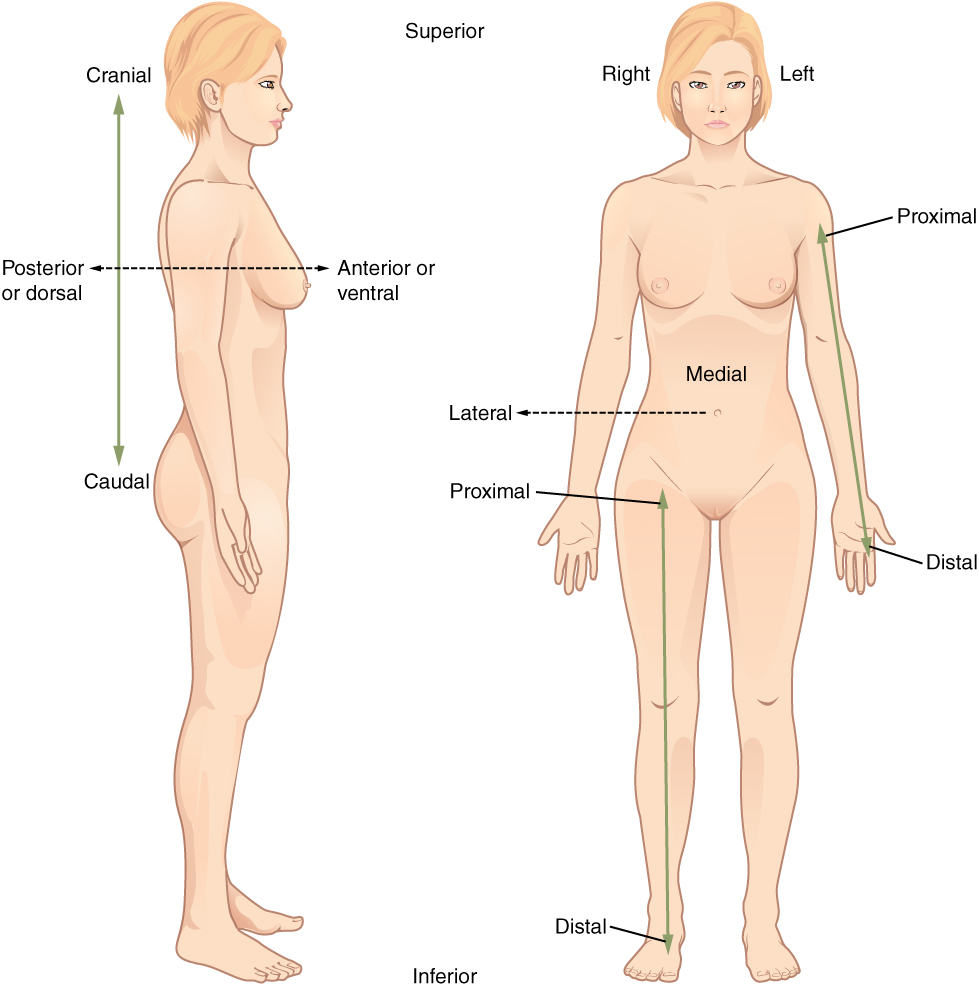

Anatomists and healthcare providers use terminology that can be confusing to the uninitiated. However, the purpose of this language is not to confuse, but rather to increase precision and reduce medical errors and eliminate ambiguity. Directional terms are used in anatomy and physiology to help describe the position of a certain area or structure relative to the body or other specific structures. These terms are often used in relation to the anatomical position (Figure 1.1). This refers to the positioning of the body when it is standing upright and facing forward, with feet flat on the ground and facing straight ahead, the arms down by the body’s sides with the palms facing forwards. This is why many diagrams and instructional videos are shown with the person/diagram standing in this manner so there is a common way of describing locations on a body using correct terminology.

Anterior and Posterior

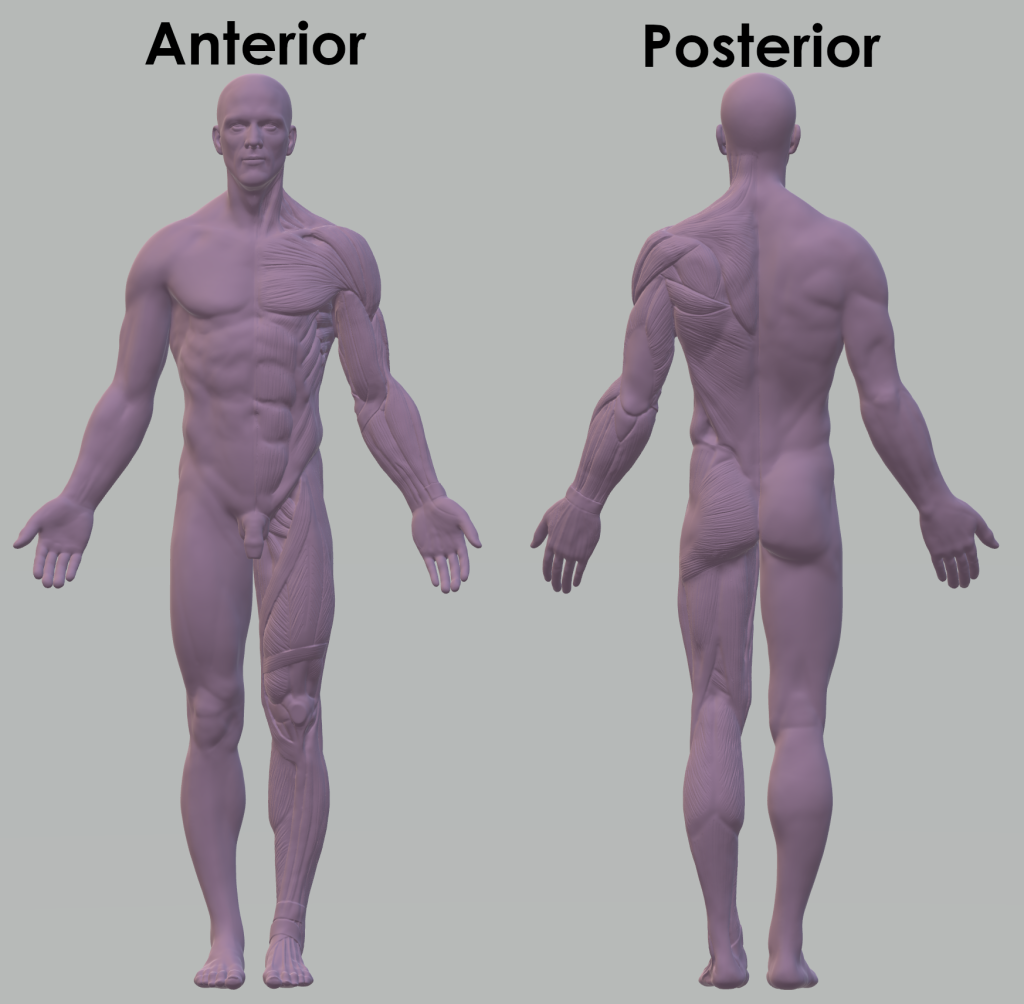

Other essential directional terms used throughout anatomy and physiology are the ones that refer to the front side and back side of a structure. This makes it easier to visualise and orientate the location of the structure and associated regions. Just like when boarding a plane, and the flight attendant tells you that your seat is located at the front of the plane, we use the term anterior to describe the front side (Figure 1.2). An example of this is saying that the belly button is located on the anterior side of the torso, or that when a body is in the correct anatomical position, the palms of the hands face anteriorly.

When referring to something being towards the back of a structure, this is referred to as being posterior (Figure 1.2). As an example, the spine sits on the posterior side of the torso, or the calves are on the posterior side of the leg or the spine is posterior to the umbilicus (navel or belly button). These examples refer to structures that are located near or directly at the back of the body and can also refer to the relative positioning of the structures.

Supine and Prone

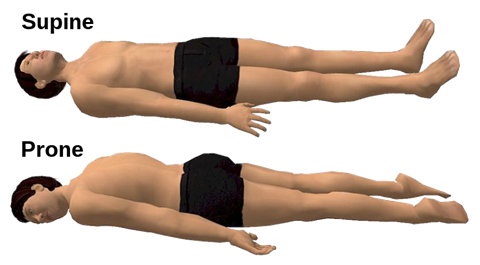

As the anatomical position shifts from standing upright to lying down on the back, this is called the supine position (Figure 1.3). In the supine position, the person remains in the anatomical position, with the palms and toes facing upwards towards the ceiling. When the anatomical position shifts to lying down on the stomach while remaining in the anatomical position, this is known as the prone position (Figure 1.3). In the prone position, the person lies on their stomach with the palms and toes facing down towards the surface they are lying on (usually a bed).

Midline

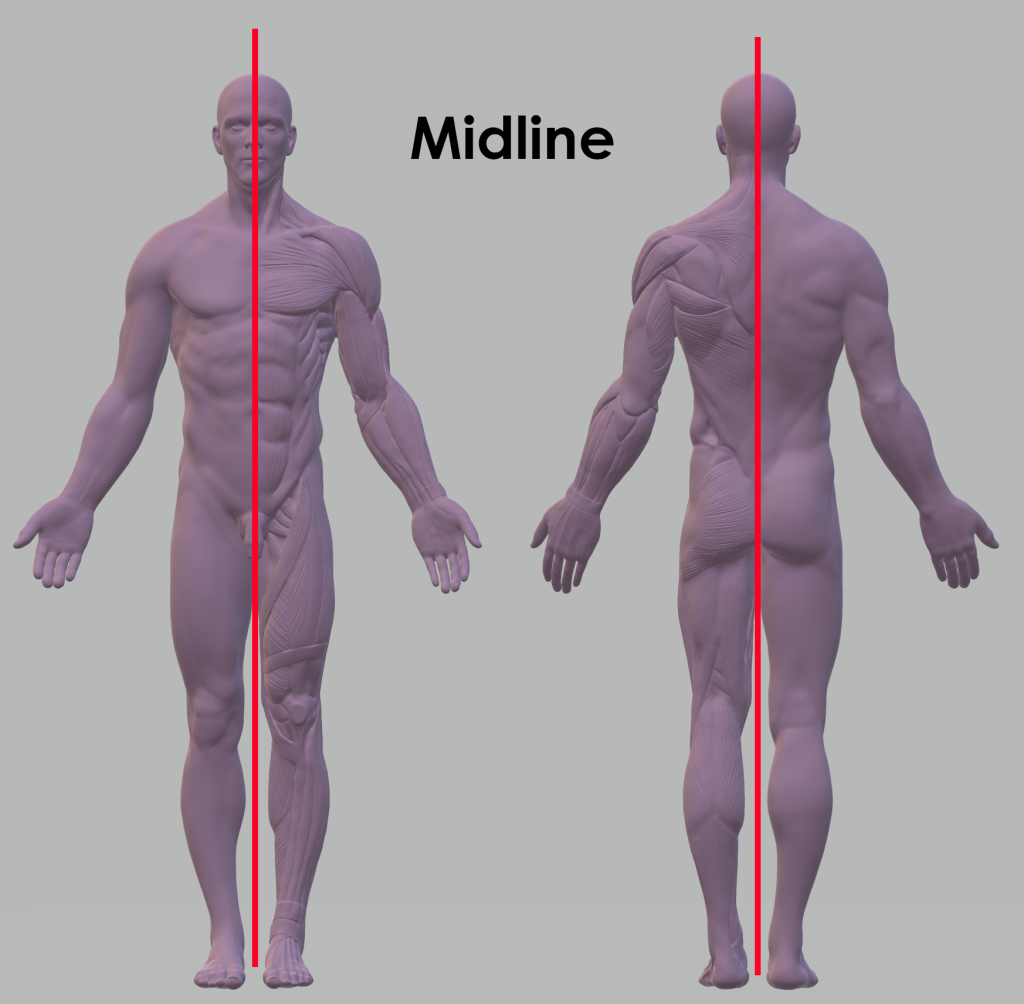

When looking at a body in the anatomical position, it can be useful to think of it as a world map. On a map, coordinates are used to point to a specific region, or broad directional terms like north, south, east and west – the same thing can be done with anatomical directional terms, many of which refer to or relate to the midline (Figure 1.4). The midline is an imaginary line that goes down vertically in the middle of the body, separating it into equal halves, the right and left side of the body. On a world map, this would be the same as prime meridian, which is the Line of Longitude with 0°.

Lateral and Medial

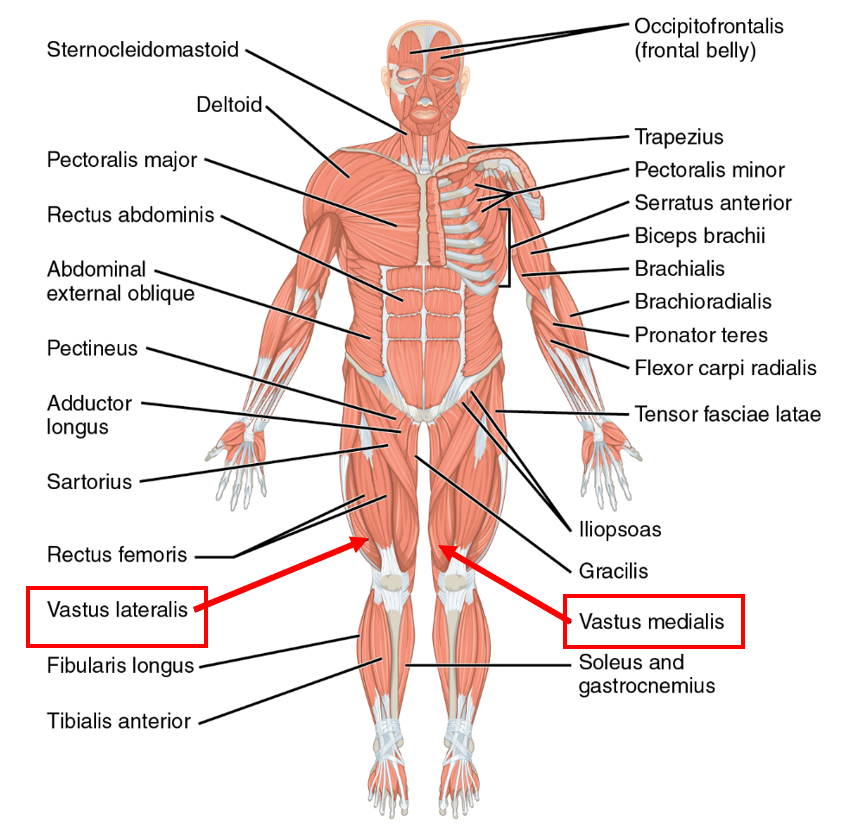

Once the location of the midline is established, if a structure is located further away from midline (toward the outside edge of the body), that is referred to as lateral (Figure 1.5). This refers to something that is to the ‘side’ of the body, and away from the midline, for example, the ears are lateral to the eyes, or the arms are lateral to the torso. The names of some structures of the body can incorporate the location from the midline such as the vastus lateralis muscle, which is one of the four muscles of the quadriceps (‘Quads’) that make up the thigh (Figure 1.5). This muscle sits on the outer side of the thigh (lateral position).

The opposite can be said about a structure that sits towards or on the midline, this is referred to as medial. As an example, the nose is medial to the eyes, or the big toe (the hallux or first digit of the foot) is medial to the little toe (fifth digit of the foot). Using the example of the quadriceps muscles of the thighs, the vastus medialis muscle is located towards the inner thigh and thus closer to the midline (Figure 1.5).

Superior and Inferior

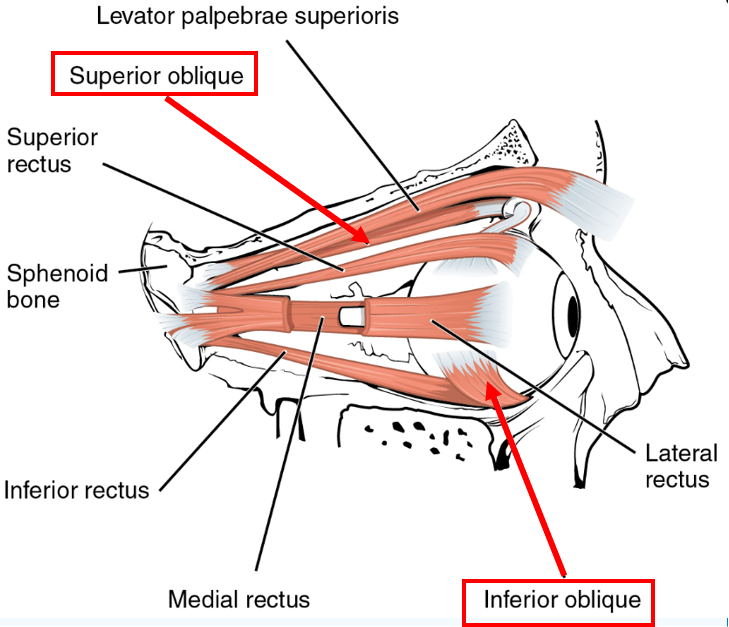

Another direction that is often needed is what is found at the top and what sits on the bottom. In anatomy and physiology, when referring to something that is at the upper part of a structure, or towards the head, this is referred to as being superior. As an example, the head is superior to the torso, or the elbow is superior to the hand (remember the anatomical position). Some muscles are also named after their superior position, for example the superior oblique of the eye (Figure 1.6), is found above (superior) the eyeball. More detail regarding the anatomy of the eye will be discussed in later modules. When referring to something above, and specifically the head, the term ‘cranial’ can be used instead of superior, as noted in some of the later modules when discussing the cranial bones and cranial nerves.

When a structure is located towards the bottom of another structure, or away from the head, this is referred to as being inferior (Figure 1.6). As an example, the foot is inferior to the knee, or the thighs are inferior to the torso. Similarly, to the superior oblique muscle of the eye, some muscles are also named after their inferior position, such as the inferior oblique muscle of the eye (Figure 1.6). When describing something at the end, or the back, or towards the tail of an organism, the term ‘caudal’ can be used.

Proximal and Distal

Sometimes when discussing anatomical regions or structures, it is not always as simple as up or down, towards the head or towards the toes. In these situations, different terminology is used which focuses on something being closer towards the centre of the body, or towards a point of attachment. This is when the term proximal (Figure 1.7) is used. As an example, the neck is proximal to the eyes, meaning that the neck is closer towards the centre of the body compared to the eyes. Another example would be that the shoulder is proximal to the elbow, where once again the shoulder is closer towards the centre of the body compared to the elbow.

When a structure or region is further away from the centre of the body, or away from the point of attachment, this is referred to as being distal (Figure 1.7). Using the same examples as above, the eyes are distal to the neck, meaning that the eyes sit further away from the centre of the body when compared to the neck. The elbow is distal to the shoulder, where the elbow is situated further away from the centre of the body in comparison to the shoulder.

Superficial and Deep

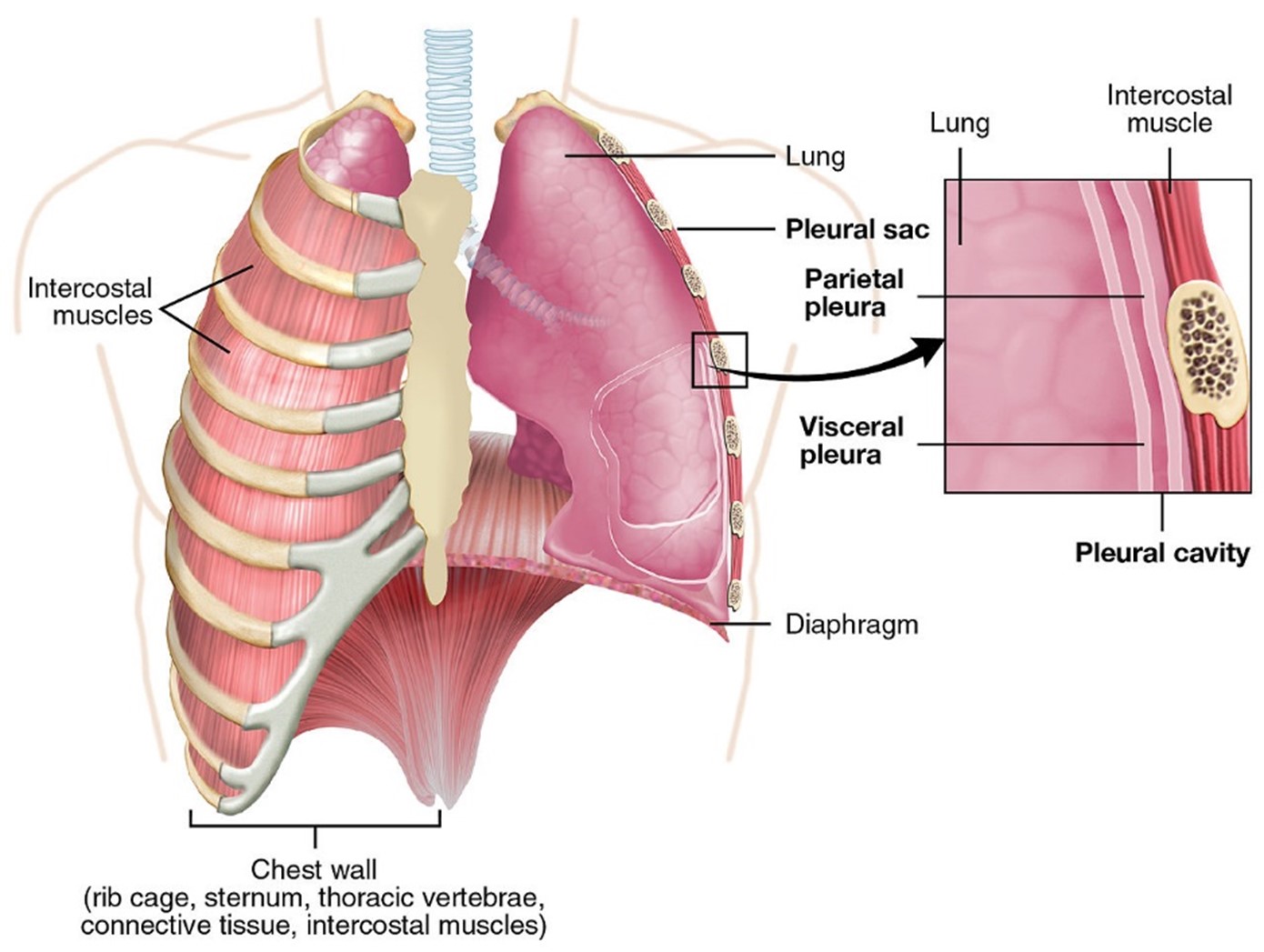

There are also terms to describe how close a structure is to a surface – either close to a surface or deeper inside a structure. When referring to something being close to, or even on, the surface of the body, this is termed as being superficial. The opposite is true for a structure that we refer to as deep, where the structure or area is located away from the surface of the body. A good example of this is skin and bone. Skin sits superficially on the outside of the body, while the bones are located deep within the body. Another example are ribs, which sit superficial to the lungs, which are found deeper, underneath the ribs (Figure 1.8).

Standard reference position used for describing locations and directions of anatomical structures in the human body.

In front of or front.

In behind or behind.

Face up.

Face down.

Median vertical line that runs the length of the body separating it into left and right hemispheres.

Towards the median.

Towards the top of the head.

Towards the head.

Towards the feet.

Towards the tail

Closer or towards the trunk or the point of origin of the body part.

Away or farthest away from the trunk or the point of origin of the body part.

Nearer to the surface.

Farther from the surface.