20 Circadian (Daily) Rhythms

In this section

Content in this section includes:

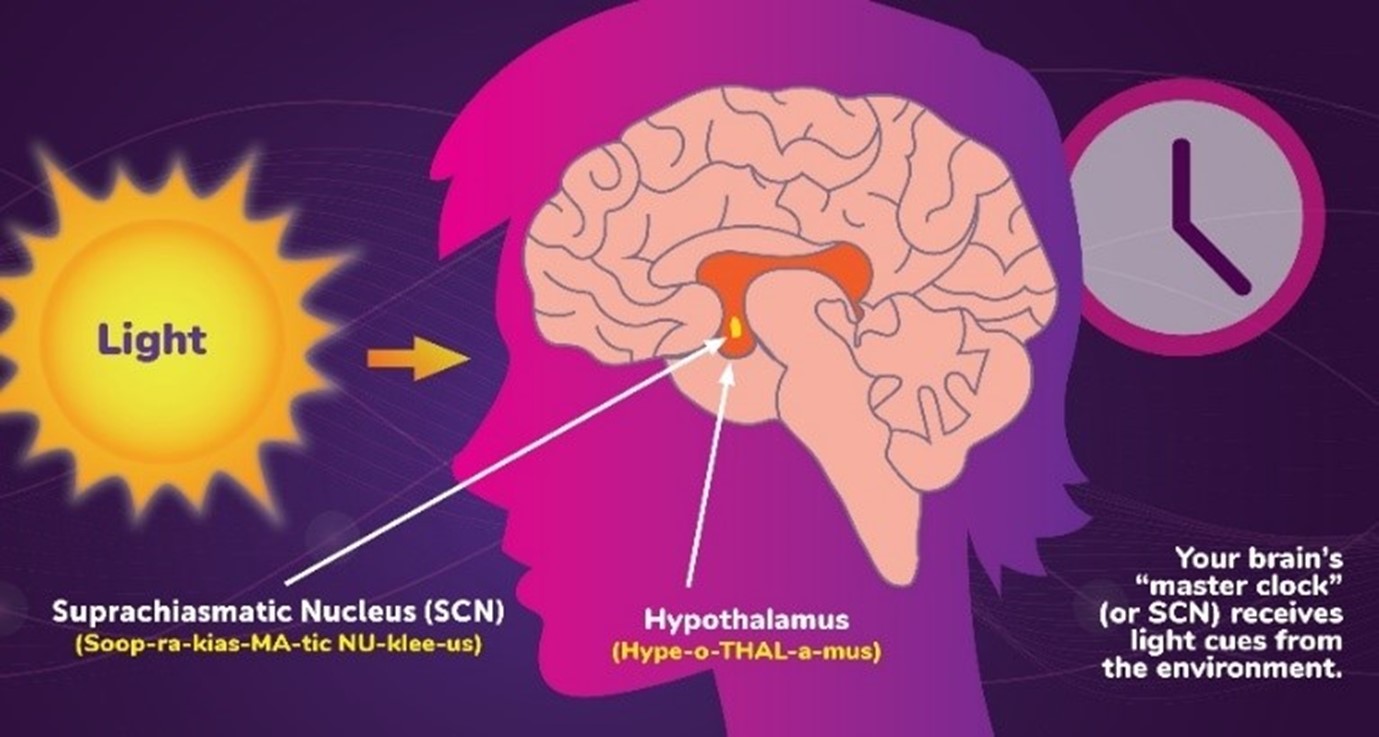

In the brain, the hypothalamus, which lies superior to the pituitary gland, is a main centre of homeostasis. Homeostasis is the tendency to maintain a balance, or optimal level, within a biological system. The brain plays a key role in the timing of body functions and the brain’s clock mechanism is located in an area of the hypothalamus known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The axons of light-sensitive neurons in the retina of the eye provide information to the SCN based on the amount/intensity of light present, allowing this internal clock to be synchronised with the outside world via the light-dark cycle. The SCN is integral in perceiving changes in light (input from the photoreceptive cells) in driving biological rhythms (the internal rhythms of biological activity). The SCN also regulates the production of the hormone melatonin (from the pineal gland; known as a darkness hormone), with increased production when light is low (ie during the night) and lower production when light levels are greater (eg during daylight hours) (Figure 6.5).

While the human body has a number of intrinsic biological rhythms, such as a woman’s menstrual cycle, nominally reoccurring every 28 days, not all cyclical patterns of biological rhythms occur over the same time frame, some can be much shorter.

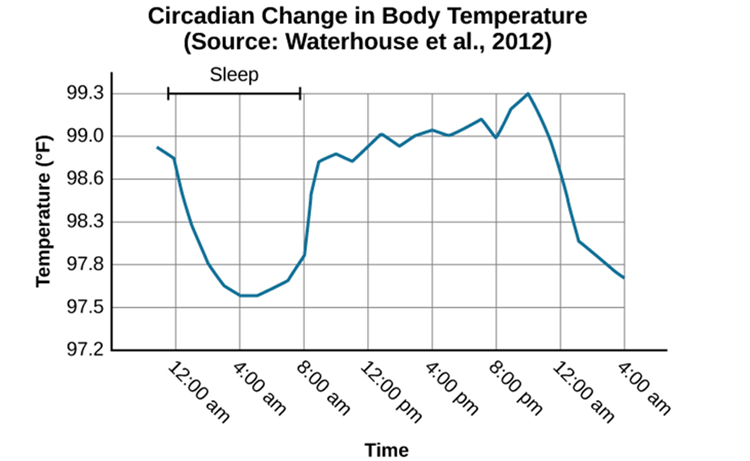

A circadian rhythm is a type of biological rhythm that takes place over a period of about 24 hours. The sleep-wake cycle, which is linked to the environment’s natural light-dark cycle, is perhaps the most obvious example of a circadian rhythm, but there are also daily fluctuations in heart rate, blood pressure, blood glucose and body temperature. Body temperature, for example, fluctuates cyclically over a 24-hour period (Figure 6.6) with alertness associated with higher body temperatures and sleepiness with lower body temperatures.

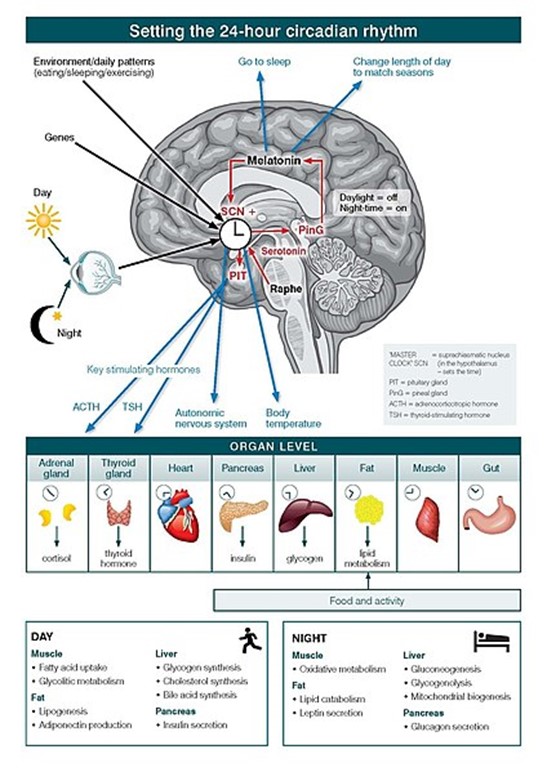

Circadian rhythms occur and influence a number of important functions in the body (Figure 6.7) and disruption of these rhythms can adversely affect health.

Disruption of Circadian Rhythms

Generally, and for most people, the circadian cycles are aligned with the outside world – most people sleep during the night and are awake during the day. There are individual differences in regard to the sleep-wake cycle, with some people saying they are morning people, while others would consider themselves to be night owls. These individual differences in circadian patterns of activity are known as a person’s chronotype and research demonstrates that morning larks and night owls differ with regard to sleep regulation. Sleep regulation refers to the brain’s control of switching between sleep and wakefulness as well as coordinating this cycle with the outside world.

One important regulator of sleep-wake cycles is the SCN and the ‘darkness’ hormone melatonin, produced by the pineal gland. Melatonin release is stimulated by darkness and inhibited by light and this hormone is responsible for many aspects of energy metabolism and glucose homeostasis and with a probable role in immune function, as well as the regulation of other biological rhythms.

Disruption of Normal Sleep

Whether a morning person or a night owl or somewhere in between, there are situations in which a person’s circadian clock gets out of synchrony with the external environment. One way that this happens involves travelling across multiple time zones. When this occurs, people often experience jet lag. Jet lag is a collection of symptoms that results from the mismatch between the internal circadian cycles and the environment. These symptoms include fatigue, sluggishness, irritability and insomnia (ie a consistent difficulty in falling or staying asleep for at least three nights a week over a month’s time) and these effects may be diminished by taking oral melatonin.

Individuals who do rotating shift work are also likely to experience disruptions in circadian cycles. Rotating shift work refers to a work schedule that changes from early to late on a daily or weekly basis. For example, a person may work from 7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. on Monday, 3:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. on Tuesday, and 11:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. on Wednesday. In such instances, the individual’s schedule changes so frequently that it becomes difficult for a normal circadian rhythm to be maintained. This often results in sleeping problems, and it can lead to signs of depression and anxiety. These kinds of schedules are common for individuals working in health care professions and service industries, and they are associated with persistent feelings of exhaustion and agitation that can make someone more prone to making mistakes on the job. Rotating shift work has pervasive effects on the lives and experiences of individuals engaged in that kind of work, which is clearly illustrated in stories reported in a qualitative study that researched the experiences of middle-aged nurses who worked rotating shifts.

While disruptions in circadian rhythms can have negative consequences, there are things that can be done to help realign the biological clocks with the external environment. Some of these approaches, such as using a bright light at an appropriate time (Figure 6.8), have been shown to alleviate some of the problems experienced by individuals suffering from jet lag or from the consequences of rotating shift work. Because the biological clock is driven by light, exposure to bright light during working shifts and dark exposure when not working can help combat insomnia and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

So… what about light pollution? Is excess light in the environment or specific types of light detrimental to your circadian rhythm and therefore your health?

It has been estimated that over 80% of people in the world have been impacted by light pollution mainly due to increased urbanisation, with artificial light at night and blue light representing the major current light pollution. As the SCN and light regulate so many of the body’s functions, light pollution has been associated with a number of health concerns, including obesity, sleep disorders and even some cancers, due to the disruption to circadian rhythms.

Sleep Debt

A person with a sleep debt does not get sufficient sleep on a chronic basis. The consequences of sleep debt include decreased levels of alertness and mental efficiency. Interestingly, since the advent of electric light, the amount of sleep that people get has declined. While modern society certainly welcomed the convenience of having the darkness lit up, it suffers the consequences of reduced amounts of sleep, because people are more active during the night-time hours than human ancestors were. As a result, many people sleep less than 7–8 hours a night and accrue a sleep debt. While there is tremendous variation in any given individual’s sleep needs, it is estimated that newborns require the most sleep (between 12 and 18 hours a night) and that this amount declines to just 7–9 hours required by an adult. If an individual lies down to take a nap and falls asleep very easily, chances are they may have sleep debt.

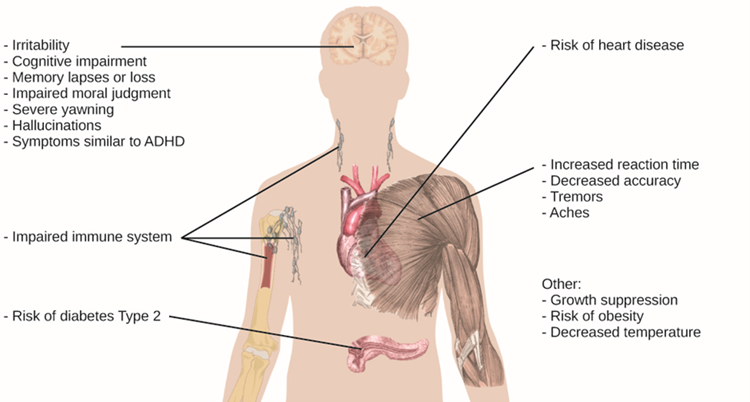

Sleep debt and sleep deprivation have significant negative psychological and physiological consequences (Figure 6.9), including decreased mental alertness and cognitive function. In addition, sleep deprivation may result in depression-like symptoms. These effects can occur as a function of accumulated sleep debt or in response to more acute periods of sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation is associated with obesity, increased blood pressure, increased levels of stress hormones and reduced immune functioning. Some research suggests that sleep deprivation affects cognitive and motor function as much as, if not more than, alcohol intoxication. Research shows that the most severe effects of sleep deprivation occur when a person stays awake for more than 24 hours or following repeated nights with fewer than four hours asleep. This can result in irritability, distractibility and impairments in cognitive and moral judgment and if someone stays awake for 48 or more consecutive hours, they may experience hallucinations.

Copyright Information: Sources from which this module has been adapted from can be found here.

Steady state of body systems that living organisms maintain.

Located in the anterior hypothalamus, regulates most circadian cycles in the body.

Specialised extension of a neuron that conducts electrical impulses away from the neuron's cell body towards other neurons or effector cells, such as other neurons, muscles or glands.

Ability to detect or respond to light.

Internal perception of the daily cycle of light and dark based on retinal activity related to sunlight.

Behavioural manifestation of an individual's internal body clock, or circadian rhythm. It essentially categorises a person's natural inclination toward being more active and alert at certain times of the day.

The brain’s control of switching between sleep and wakefulness in coordination of this cycle with the outside world.

Located in the anterior hypothalamus, regulates most circadian cycles in the body.

Important hormone in the regulation of sleep-wake cycles.

Mismatch between internal circadian cycles and the environment that result in several symptoms.

Work schedule with frequent changes from early to late on a daily or weekly basis.

Insufficient sleep on a chronic basis accumulates a sleep debt which results in decreased levels of alertness and mental efficiency.

Health condition or disease that persists over a long period of time.