Thinking

Douglas Eacersall; Tyler Cawthray; and Akshay Sahay

Introduction

Thinking is a core skill that university educators aim to teach students. Learning different ways of thinking and how to resolve or respond to problems creates well-rounded learners who are capable of breaking down issues or problems into manageable parts, adapting to changing situations or contexts and devising creative or novel solutions. These are key characteristics required in the 21st century digitally focused work environment.

This chapter will provide you with an overview of different types of thinking, namely, creative, critical and analytical and give guidance on how you can practise these approaches. It will then cover the practical use of these skills for your study, including applying creative, critical and analytical thinking skills to problem solving and your university assignments. In this way, the chapter provides you with the information and thinking skills to begin positively affecting your study outcomes right now.

Creative thinking

Has anyone ever told you that you have a creative flair? If so, celebrate! That’s a good personality trait to nurture. Creativity is needed in all occupations and during all stages of life. Learning to be more in tune with your own version of creativity can help you think more clearly, resolve problems, and appreciate setbacks. You’re creative if you repurpose old furniture into a new function. You’re also creative if you invent a new biscuit recipe for a friend who has a nut allergy. Further, you’re using creativity if you can explain complex biological concepts to your classmates in your tutorial or workshop. Creativity pops up everywhere. When creative thinking comes into play, you’ll be looking for both original and unconventional ideas, and learning to recognise those ideas that improve your thinking skills all around.

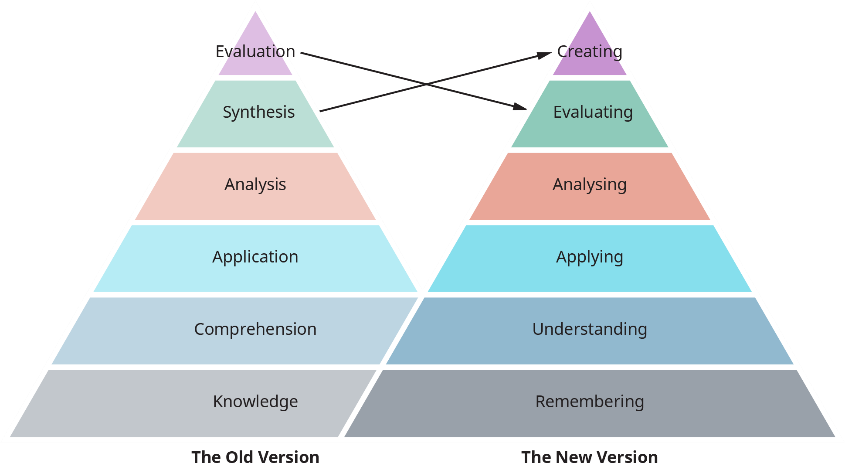

Creativity doesn’t always present itself in the guise of a chart-topping musical hit or other artistic expression. We need creative solutions throughout the workplace, institutions for learning and in everyday life—whether in the home, board room, emergency room, or classroom. It was no fluke that the 2001 revised Bloom’s cognitive taxonomy, originally developed in 1948, placed a new word at the apex—create (See Figure 17.2). We all need to use and develop the lower thinking skills including remembering, applying, and analysing, but at the top of the apex, these skills can be incorporated to create new ideas leading to innovation and invention.

Many assessments and lessons you’ve seen during your schooling have likely been arranged with Bloom’s taxonomy in mind. Regurgitating the minute details of Goldilocks or Romeo and Juliet demonstrates far less comprehension than fashioning an original ending that turns the tables, or developing a board game from the story. Author Gregory Maguire used the base plot of L. Frank Baum’s 1900 book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz to create the 2003 smash-hit Broadway musical Wicked that tells the story from the perspective of the Wicked Witch of the West, making her a sympathetic character. This creative approach calls for far more critical and creative thinking than memorising facts. Creating new out of old or new out of nothing is how we ended up with manned space flight, mobile phones, and rap music. Continuing to support creativity in whatever form it takes will be how we cure cancer, establish peace, and manipulate the time-space continuum. Don’t shortchange your own creativity.

You may feel like you cannot come up with new ideas, but even the process of combining and recombining familiar concepts and approaches is a creative act. A kaleidoscope creates a nearly infinite number of new images by repositioning the same pieces of glass. It is certainly a pretty metaphor of idea generation, but even if old ideas are reworked to create new solutions to existing problems or we embellish a current thought to include new ways of living or working, that renewal is the epitome of the creative process.

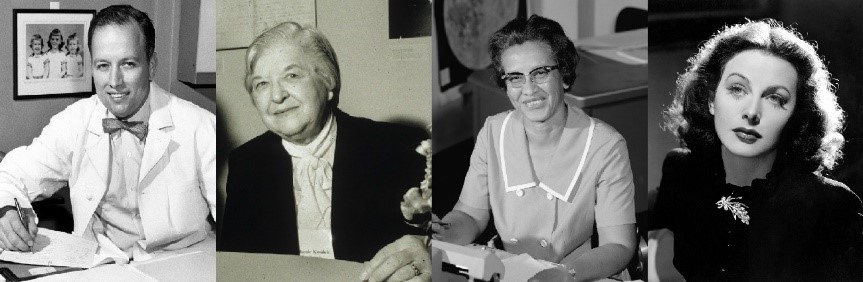

It’s common to think of creativity as something used mostly by traditional artists—people who paint, draw, or sculpt. Indeed, artists are creative, but think of other fields in which people think creatively to approach situations in their discipline. The famous heart surgeon Dr. Denton Cooley didn’t have an exact model when he first implanted an artificial heart. Chemist Stephanie Kwoleck discovered life-saving Kevlar when she continued work on a substance that would usually be thrown away. Early US astronauts owed their ability to orbit and return to Earth based on creative uses of mathematics by people like Katherine Johnson. Inventor and actress Hedy Lamarr used diagrams of fish and birds to help aviation pioneer Howard Hughes produce faster airplanes. Indeed, biomimicry, an approach to innovation that seeks sustainable solutions to human challenges by emulating nature’s time-tested patterns and strategies, is now a huge field of study. This list could go on and on.

DEVELOPING CREATIVE THINKING FOR UNIVERSITY

There are many activities you can undertake, as part of your university studies, to develop your creative thinking and supercharge your problem solving and academic success.

Creative Spaces

Setting up your study space in a certain way can foster more creative thinking. Personalising the space with personal and inspiring objects can help remind you of your own unique perspectives while at the same time inspiring new and innovative thoughts. Try to design your study space with comfort and relaxation in mind. You should aim for a space that you want to spend time in and that creates a stress-free environment. If you are relaxed and uninhibited, you will be more open to innovative ideas and the creative process. For more suggestions on setting up your study space, see the chapter Study Space.

Notebook

Keep a notebook to write down and explore ideas. This can be about anything that comes to mind (e.g. brainstorming ideas for a project), or could use creative questions to generate ideas for a particular academic task. For example, how would I develop this product if I was the richest person on earth, or how would I solve this problem as a superhero, or how would I present this idea as a TikTok video? Approaching a problem like this can be a good way to think creatively, outside of the box, and get ideas flowing. Ideas can also be creatively explored through graphical representations. In your notebook you might try sketching ideas as illustrations, making a collage of ideas from cut out pictures, or drawing a concept map.

Creativity Driven Learning

You can develop your creative thinking skills by using creative means to focus your learning. This might be used to aid deep learning or to assist with surface level memorisation of course content. For example, you could write a short story to help you remember and understand certain core concepts of a particular theory or you could write a song, where the lyrics help to memorise key information.

Analytical thinking

Different forms of thinking can be useful in many situations. When we work out a problem or situation systematically, breaking the whole into its component parts for separate analysis, to come to a solution or a variety of possible solutions, we call that analytical thinking. Characteristics of analytical thinking include setting up the parts, using information literacy, and verifying the validity of any sources you reference. Although the phrase analytical thinking may sound daunting, we do this sort of thinking in our everyday lives when we brainstorm, budget, detect patterns, plan, compare, solve puzzles, and make decisions based on multiple sources of information. Consider the thinking that goes into the logistics of a “dinner and a movie” date—where to eat, what to watch, who to invite, what to wear, popcorn or ice-cream. These decisions all involve analytical thinking skills.

Many employers specifically look for candidates with analytical skills. If everything always went smoothly on the shop floor or in the office, we wouldn’t need front-line managers, but everything doesn’t always go according to plan or corporate policy. Your ability to think analytically could be the difference between getting a good job and being passed over by others who prove they are stronger thinkers. A mechanic who takes each car apart piece by piece to see what might be wrong instead of investigating the entire car, gathering customer information, assessing the symptoms, and focusing on a narrow set of possible problems, is not an effective member of the team. Some career fields even have set, formulaic analyses that professionals in those fields need to know how to conduct and understand, such as a cost analysis, a statistical analysis, or a return-on-investment analysis.

DEVELOPING ANALYTICAL THINKING FOR UNIVERSITY

There are many ways you can develop your analytical thinking for university. Some of these include identifying and examining relationships between theories and ideas, and making use of real-world examples.

Identify and examine relationships

In developing analytical thinking, it is important to identify the parts of an issue, theory or idea you are studying, and examine how they relate to each other and other ideas. This can be undertaken when you are listening to a lecture, taking notes from the textbook or working on organising information for an assignment. For example, once you have taken notes and/or studied a particular part of the course, you could try and relate it to other sections of the course by writing notes that seek to explain and synthesise how the different sections relate (or don’t relate) to each other. This type of activity will begin to develop your analytical thinking skills in the context of your university course.

Apply knowledge to real-world examples

When trying to learn new information, it can be helpful to relate it to real life examples rather than trying to learn it through memory alone. This is more likely to result in learning by understanding and will exercise your analytical thinking skills. This is because this type of learning requires you to identify the relevant course concepts and analyse them in terms of their application in the real world rather than learning them in isolation. For instance, if you were studying law, there are many abstract law concepts to remember — the rule against perpetuities; the differences between defamation, slander and libel; the application of jurisprudence. If we use defamation, slander and libel as an example, trying to differentiate the slight differences between the definitions of these three terms can be confusing. If however you apply these definitions to a high profile celebrity defamation case, you will engage your analytical thinking skills in understanding the contrasting aspects of these concepts and connecting them to relevant elements of the real world example. This helps you to remember them and also understand their application.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking has become a buzz phrase in education and corporate environments in recent years. The definitions vary slightly, but most agree that thinking critically includes some form of judgement that thinkers generate after careful analysis of the perspectives, opinions, or experimental results present in a particular problem or situation. Before you wonder if you’re even capable of critical thinking, consider that you think critically every day. When you grab an unwashed T-shirt off the top of the pile on the floor of your bedroom to wear to university but then suddenly remember that you may see the person of your dreams on that route, you may change into something a bit less dishevelled. That’s thinking critically—you used data (the memory that your potential soul mate travels the same route you use on that day on campus) to change a sartorial decision (dirty shirt for clean shirt), and you will validate your thinking if you do have a successful encounter with said soul mate.

Likewise, when you decide to make your lunch rather than just grabbing a bag of chips, you’re thinking critically. You must plan, buy the food, possibly prepare it, arrange to carry the lunch with you, and you may have various reasons for doing that—making healthier eating choices, saving money for an upcoming trip, or wanting more quiet time to unwind instead of waiting to purchase food. You are constantly weighing options, consulting data, gathering opinions, making choices, and then evaluating those decisions, which is a general definition of critical thinking.

Consider the following situations and how each one demands your thinking attention. Which do you find most demanding of critical thinking and why?

- Participating in competitive athletic events

- Watching competitive athletic events

- Reading a novel for pleasure

- Reading a textbook passage for study

Developing Critical Thinking for University

Critical thinking forces you to determine the actual situation under question and to determine your thoughts and actions around that situation. Critical thinking differs according to the subject you’re thinking about, and as such it can be difficult to pin down a formula to make sure you are doing a good job of thinking critically in all situations. There are however some general approaches you can take during your university studies to improve your critical thinking skills. These include questioning everything and participating in academic discussion.

Question Everything

In order to exercise your critical thinking, it is important that you question everything. You should never assume information is accurate or correct. Even information from seemingly credible sources such as the news, your textbook or your lecturers should be scrutinised. To exercise your critical thinking skills, you should identify and evaluate the evidence to make an informed decision about the information. You should question the credibility of the source and the evidence that has been provided to support the information. Is it accurate? Is it reliable? Is it sufficient? For more information on methods for measuring a source’s credibility, see the chapter Working with Information.

Participate in Discussions

Whether it is through an online forum or in person, participating in academic discussion can improve your critically thinking abilities. Discussions with peers and your lecturers will help you to engage with and evaluate different perspectives. This aids you in critically formulating and expressing your own opinions and further refining your critical analysis skills through dialogue and constructive debate.

PRACTICAL APPLICATION

Now that you understand a bit more about the different types of thinking skills and how to develop them in the university context, let’s examine how to apply them to problem solving and assessment. These are some of the most useful applications of thinking skills you will experience at university.

Problem Solving

Problem solving is part of our everyday and study life and often incorporates the different types of thinking discussed above. Many of the tasks you are required to complete as part of your university studies will involve multiple thinking skills and elements of problem solving. When solving a problem, we generally have a sequence of processes that we follow, with related types of thinking, to effectively resolve or to dissolve a problem. In order to do this, we may use some variation of the following strategies:

- Identify and determine what the problem is (analytical)

- Explore (brainstorm) as many possible solutions to the problem (creative)

- Recognise and understand that there will be varying perspectives from different people (analytical)

- Explore the results further by researching and documenting pros and cons for all the possible solutions (analytical/critical)

- Select the best solution (critical)

- Communicate your findings to all involved (analytical/critical/creative)

- Establish logical action items based on your analysis (analytical/critical)

The image below represents the problem solving cycle:

To determine the best solution to a problem, it is important to generate a wide array of solutions. When coming up with potential solutions during a brainstorming session, it is important to remember that there is no right or wrong answer. The purpose of this is to establish different solutions that can potentially solve the problem. Once you have a variety of different solutions, you can start evaluating them to see how they fit within the context of the problem and weighing up pros and cons. This will help you to narrow down your solutions until you find the best one. Once you have established this, you can communicate and implement the solution. Afterwards evaluate whether the problem has been resolved or not. Evaluation is an important part for closing the loop when problem solving. If the problem is not resolved, then go through the process again.

Determining the best approach to any given problem and generating more than one possible solution constitutes the complicated process of problem-solving. People who are good at these skills are highly marketable because many jobs consist of a series of problems that need to be solved for production, services, and sales to continue smoothly.

Think about what happens when a worker at your favourite coffee shop slips on a wet spot behind the counter, dropping several drinks she just prepared. One problem is the employee may be hurt, in need of attention, and probably embarrassed; another problem is that several customers do not have the drinks they were waiting for; and another problem is that stopping production of drinks (to care for the hurt worker, to clean up her spilt drinks, to make new drinks) causes the line at the cash register to back up. A good manager has to juggle all these elements to resolve the situation as quickly and efficiently as possible. The resolution and return to standard operations doesn’t happen without a great deal of creative, analytical and critical thinking: prioritising needs, shifting other workers off one station onto another temporarily, and dealing with all the people involved, from the injured worker to the impatient patrons.

Applied to the university setting, we can consider the different disciplines of study and the common problems and thinking skills most used within them. Creative arts students are more likely to engage in creative projects that require creative problem-solving skills. For example, a photography student may experiment with filters to communicate a mood in a picture. In a similar way, an architecture student may need to tap into creative thinking skills when considering the atmosphere of a home during the design process. When designing a bridge, engineering students may be more likely to use analytical thinking to consider the amount of load different building materials can carry. In reality though, just like the example of the coffee shop manager above, most of the problem solving we do, including at university involves a mix of different thinking skills, no matter the discipline. For example, if you are an early childhood education student outlining the logistics involved in establishing a summer day camp for children, you may need a combination of critical, analytical, and creative thinking to solve this challenge. Faced with a problem-solving opportunity, you must assess the skills you will need to create solutions. Problem-solving can involve many different types of thinking. You may have to call on your creative, analytical, or critical thinking skills—or more frequently, a combination of several different types of thinking—to solve a problem satisfactorily.

Thinking and assessment success

At university, the need to apply multiple thinking skills is evident in many of the academic tasks required, irrespective of discipline. For instance, goal setting, time management, planning, learning content, assignment writing, note taking, reading, examination and quiz preparation, oral presenting, and group work all require different combinations of creative, analytical and critical thinking skills. This section will use the example of an essay assessment to demonstrate how these different skills can be applied to contribute directly to your academic success.

Essay Writing

Successful essay writing involves several steps. These include task analysis, brainstorming, finding and evaluating sources, constructing and writing arguments with supporting evidence, and referencing (see the chapter Writing Assignments for a more detailed overview of essay tasks). Each of these steps involves different combinations of thinking skills. For example, when brainstorming topics, creative and analytical thinking are important but if you are evaluating sources then critical thinking will be used. For referencing, you will need to be very accurate and follow a predetermined method, so analytical and critical skills will be useful but creative thinking skills will not be as relevant.

Task Analysis (analytical and critical thinking)

Task analysis involves breaking the assignment task down into its relevant parts and therefore involves mostly analytical thinking skills. By breaking the task into parts, you can more effectively analyse what is required and how these parts relate to the overall task. There is also some critical thinking required in understanding the requirements of each part of the task and the language used to communicate this. You must critically assess the meaning of these words and what each requirement is actually asking you to do. For example, it may require that you compare and contrast, describe, evaluate and/or justify. The analytical and critical assessment of the essay task can help you understand the essay question and ensure that you fulfil the overall essay requirements adequately.

Brainstorming (analytical and creative thinking)

In the context of essay assessments, brainstorming is used to come up with a topic and possible options to fulfil the essay requirements (e.g. answer the essay question). In this case you will mostly use analytical and creative thinking skills. You will use analytical skills to identify the individual concepts relevant to the topic and organise them according to their relationship to each other. These concepts often come from your course textbook and relevant literature and may be organised into an overall framework. This represents the concepts you believe will be useful in answering the essay question. As part of this process, creative thinking will be used to come up with novel concepts and may also be required to represent the framework visually in a concept map.

Finding and evaluating sources (critical thinking)

In order to effectively answer an essay assessment question, you will often need to engage with a great deal of information (see the chapter Working with Information). Some of that information will be factual, and some won’t. You need to be able to use your critical thinking skills to distinguish between facts and opinions so that the information you use in your essay effectively supports your arguments.

Fact: a statement that is true and backed up with evidence; facts can be verified through observation or research

Opinion: a statement someone holds to be true without supporting evidence; opinions express beliefs, assumptions, perceptions, or judgements

Of course, the tricky part is that most people do not label statements as fact and opinion, so you need to be aware and recognise the difference by using your critical thinking skills. You probably have heard the old saying “Everyone is entitled to their own opinions,” which may be true, but conversely, not everyone is entitled to their own facts. Facts are true for everyone, not just those who want to believe in them. For example, mice are animals is a fact; mice make the best pets is an opinion. Many people become very attached to their opinions, even stating them as facts despite the lack of verifiable evidence. Think about political campaigns, sporting rivalries, musical preferences, and religious or philosophical beliefs. When you are reading, writing, and thinking critically, you must be on the lookout for sophisticated opinions others may present as factual information. While it’s possible to be polite when questioning another person’s opinions when engaging in intellectual debate, thinking critically requires that you do conduct this questioning.

Basically, you need to use your critical thinking skills to evaluate the information you plan to use for your arguments and supporting evidence. This means questioning the information based on accuracy and reliability. To ensure that information is fact and not opinion it is useful to find corroborating evidence from other reliable sources. The more corroborating evidence from reliable sources, the more factual and accurate the information is likely to be. The reliability of sources should be critically evaluated by checking where the information has come from. Is the source reputable and impartial? For example, information taken from Facebook or Wikipedia is less reliable than evidence provided through an academic peer-reviewed journal. Questioning the sources in this way and making informed decisions whether to include information in your essay is exercising your critical thinking skills.

Constructing Arguments with Supporting Evidence (analytical, critical and creative thinking)

Once you have all your information gathered and you have checked your sources for accuracy and reliability you need to decide how you are going to present your well-informed analysis. This involves constructing arguments with supporting evidence and writing this in essay form (see the chapter Writing Assignments for more information on essay writing). This process involves using both critical and analytical thinking skills. Critical thinking will be used to select the best arguments and relevant supporting evidence and your analytical skills will be important in structuring the elements into a logical argument. The actual writing of the article will also involve some creative thinking as you express your arguments and ideas through the art of writing.

You will need to be careful when constructing your arguments to recognise your own possible biases. Facts are verifiable; opinions are beliefs without supporting evidence. Stating an opinion is just that. You could say “Blue is the best colour,” and that’s your opinion. If you were to find evidence to support this claim, you could say, “Researchers at Oxford University recognise that the use of blue paint in mental hospitals reduces heart rates by 25% and contributes to fewer angry outbursts from patients.” This would be an informed analysis with credible evidence to support the claim, in the context of mental hospitals.

Not everyone will accept your analysis, which can be frustrating. Most people resist change and have firm beliefs on both important issues and less significant preferences. With all the competing information surfacing online, on the news, and in general conversation, you can understand how confusing it can be to make any decisions. Look at all the reliable, valid sources that claim different approaches to be the best diet for healthy living: ketogenic, low-carb, vegan, vegetarian, high fat, raw foods, paleo, and Mediterranean. All you can do in this sort of situation is use your creative, critical and analytical thinking skills to conduct your own serious research, check your sources, and write clearly and concisely to provide your analysis of the information for consideration. You cannot force others to accept your stance, but you can use evidence in support of your thinking, being as persuasive as possible without lapsing into your own personal biases. Then the rest is up to the person reading or viewing your analysis.

Conclusion

Thinking is a core skill that is central to your ongoing learning at university and later in your career. University represents a unique opportunity to learn and test different approaches in a safe environment. The creative, analytical and critical thinking discussed in this chapter, as well as the activities provided to increase your thinking skills at university, and the practical application of thinking skills to problem solving and essay writing are a valuable guide to understanding, developing and applying thinking skills to your university study.

Key points

- Thinking and problem solving skills are critical to learning both at university and during your career.

- Creative thinking is the highest form of thinking as outlined in Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy. The creative process appears challenging, but simply put it requires the combination of existing ideas in new ways to create novel outcomes.

- Creative thinking can be developed at university through creative spaces, keeping a notebook and creativity driven learning.

- Analytical thinking requires you to break down a problem, task or issue into its smallest parts and respond to each accordingly.

- You can improve your analytical thinking by identifying and examining relationships and applying your knowledge to real-world examples.

- Critical thinking involves careful assessment or judgment of the available information, assumptions and bias to develop an informed perspective.

- Some strategies to exercise your critical thinking skills include, questioning everything and participating in discussions.

- Problem solving is a critical skill developed at university and may require all of the forms of thinking discussed above. It focuses on devising solutions.

- Creative, analytical and critical thinking are all used in different combinations to successfully complete the steps of the essay writing process.