Successful Connections

Kacie Fahey; Debi Howarth; Sarah Irvine; Leigh Pickstone; and Bianca Retallick

Introduction

University can be intimidating. Thousands of unknown faces, cryptic messages emblazoned on PowerPoints and an unending list of acronyms that can be confusing and confronting. One way to ensure you don’t get lost in the jungle is to make successful connections to the support services offered at university. This chapter begins by discussing the importance of asking for help at university, and then helps you to create your own support contact list. Next, it considers the types of varied support staff and peers you can access, followed by a look at the inclusivity of all students at universities, especially those with a disability. The chapter concludes by explaining the value of reaching out for support to maintain your mental health while studying.

Asking for Help

At university, there are many individuals and support services who can help you plan your path. Students grapple with unfamiliar university paperwork and technology with little assistance as they proudly tackle perhaps newfound roles as adult decision-makers. Seeking help is a strength, not a weakness, particularly when that help comes from well-informed individuals who have your best interests in mind. When you share your goals and include others in your planning, you develop both a support network and a system of personal accountability. Being held accountable for your goals means that others are also tracking your progress and are interested in seeing you succeed. When you are working towards a goal and sticking to a plan, it’s important to have unconditional cheerleaders in your life as well as people who keep pushing you to stay on track, especially if they see you stray. Knowing who in your life can play these supportive roles will allow you the opportunity to confidently immerse yourself in the university experience.

Your Support Contact List

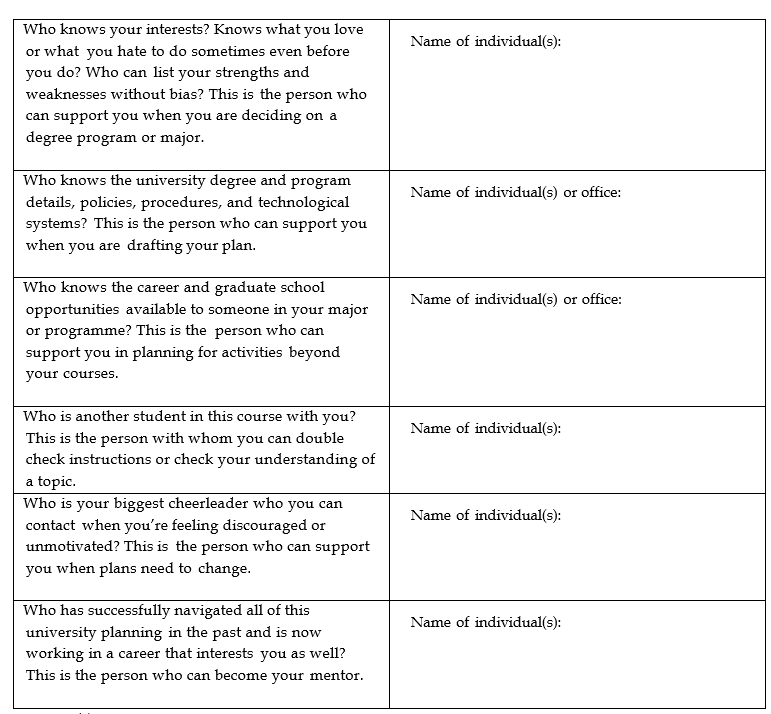

When you start a new job, go to a new school, or even fill out paperwork at a new doctor’s office, you’re often asked to provide contact information for someone who can assist in making decisions and look out for your best interests in the event of an emergency. Academic decision-making and planning doesn’t involve the same level of urgency, but it’s useful to have in mind the people in your personal life and university life who motivate and support your plans, or can assist you in setting them. Prepare your support call (text, email, or direct message) list now so that all you have to do is pick up your phone to get the support you need. Keep in mind that one person can fulfil more than one role. Use the following table to create your list.

Table 3.1. Support contact list

Academic Advisors

All universities provide resources to assist you with your academic planning. Academic advisors may also be called success coaches, mentors, or counselors. They may be staff members, or faculty members who may provide advisement as an additional role to their teaching responsibilities. Regardless of what your university calls this role, academic advisors are individuals who are able to assist you in navigating the puzzle of your academic plan and piecing your courses and requirements together with your other life obligations to help you meet your goals.

An advisor is an expert on your university and its major requirements and policies, while you are the expert on your life circumstances and your ability to manage your study time and workload. It is also an advisor’s responsibility to understand the details of your degree requirements. This person can teach you how to best utilise university resources to make decisions about your academic and career path. An advisor can help you connect with other university staff and faculty who might be integral to supporting your success. Together with your advisor, you can create a semester-by-semester plan for the courses you will take and the special requirements you will need. Even if your university does not require advising, it is wise to meet with an advisor every semester to both check your progress and learn about new opportunities that might lend you a competitive advantage in entering your career. Common functions that academic advisors can help you with include:

- Setting educational and career goals

- Selecting a major and/or minor

- Understanding the requirements of your degree

- Navigating the online tools that track the progress of your degree

- Calculating your Grade Point Average (GPA) and understanding how certain choices may impact it

- Discussing your academic progress from semester to semester

- Assisting with time management strategies

- Connecting with other support and resources at the university such as counseling, tutoring, and career services

- Navigating institutional policies such as grade appeals, admission to special programs, and other concerns

- Strategising how to make important contacts with faculty or other university administrators and staff as necessary (such as discussing how to construct professional emails)

- Discussing transfer options, if applicable

- Preparing for graduate school applications

Lecturers as Learning Partners

In primary and secondary education, the teacher often has the dual role of both instructor and authority figure for students. Children come to expect their teachers to tell them what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. University learners, on the other hand, seem to work better when they begin to think of their lecturers as respected experts who are partners in their education. The change in the relationship for you as a learner accomplishes several things: it gives you ownership and decision-making ability in your own learning, and it enables you to personalise your learning experience to best fit your own needs. For the lecturer, it gives them the opportunity to help you meet your needs and expectations, rather than focusing all their time on trying to get information to you.

The way to develop learning partnerships is through direct communication with your lecturers. If there is something you do not understand or need to know more about, go directly to them. When you have ideas about how you can personalise assignments or explore areas of the subject that interest you or better fit your needs, ask them about it. Ask your lecturers for guidance and recommendations, and above all, demonstrate to them that you are taking a direct interest in your own learning. Most lecturers are thrilled when they encounter students who want to take ownership of their learning, and they will gladly become a resourceful guide for you.

Mentors

When making academic decisions and career plans, it is also useful to have a mentor. A mentor is an experienced individual who helps to guide a mentee. A good mentor for a student engaged in academic and career planning is someone knowledgeable about the student’s desired career field, is more advanced in their career than an entry-level position, or who is skilled and qualified as a Career Development Practitioner. This person models the type of values and behaviours that are essential to a successful career, and helps the student better understand their own values and strengths.

Your university may be able to connect you with a mentor through an organised mentorship program or through the alumni association. The Career Development service, available to the student body at many Australian universities, may offer Work Integrated Learning opportunities and the chance to connect with potential mentors (Hora et al., 2020). Additionally, student/staff partnership projects facilitate connection between students and potential mentors (Cook-Sather et al., 2014) Remember, you can also find a mentor by reaching out to family, friends, and contacts who work in your field of interest, and through applying for membership of professional associations and organisations related to your field.

Peers

Aside from the professional support personnel there will be opportunities to learn from more experienced students who can help you understand coursework and the university environment in a less intimidating way (Kimmins, 2013). Study groups and Peer Assisted Learning programs are offered at many Australian universities. These programs are academic support programs rather than mentoring programs, providing opportunity for students to study collaboratively with peers to improve their academic learning skills, to develop connections, and to become more comfortable with the university environment (Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005). By learning with other students, you can share the learning and study journey in your chosen discipline.

Peers as Mentors

Peer mentoring occurs through both formal and informal processes at many universities. Programs facilitated through the university often take place throughout the first few months of the academic year; participating can help you become accustomed to university life (Shaniakos, T., Penttinen, L., & Lairio, M., 2014).  Connection with a peer mentor can assist you to become part of the learning community, and to learn about the range of supports available to you (Christie, 2014).

Connection with a peer mentor can assist you to become part of the learning community, and to learn about the range of supports available to you (Christie, 2014).

Peer mentors and mentees are people of similar age and experience, who work together to strengthen social supports, to share information, to give feedback, and to nurture friendship (Terrion, J.L., & Leonard, D, 2007). Because peer mentors are similar in experience to you as a mentee, they can help smooth the way as you step into a new environment (Christie, 2014).

Students with Disabilities

Studying as a Student with a Disability

Students with disabilities make valuable contributions to university life and academia, therefore it is important to ensure accessibility and support are widely available and commonplace. By making your educational institution aware of your individual situation regarding living with a disability, or caring for others with a disability, you will give yourself the best chance of study success. This does not mean you have to let every university staff member know about your particular situation, but it may be useful to let lecturers, tutors and disability officers know of your specific circumstance. Just like anyone else, under the law, students with disabilities are entitled to the same education that universities provide to students without disabilities. While studying with a disability can still create challenges for students, significant progress has been made over the past few decades as the government, learning institutions, and students gain a greater awareness of accessibility needs. Now, students with disabilities find that they have more appropriate student services, campus accessibility, and academic resources that can make attendance and academic success possible. Due to this increased support and advocacy, Australian universities have seen an increase of students with disabilities enrolled in study.

Policy and Legislative Environment

Universities in Australia are governed by State and Commonwealth legislation, in particular the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth). This legislation requires that all people should be given equal rights, equal opportunity, and equal access to education. Australian universities are required to make provisions for access to their facilities, online and face-to-face services, and academic supports for all students including, those who have a disability. Higher education institutions also have policies and procedures, as well as staff, to ensure the right settings and equipment are available to enable all students to demonstrate their ability and capabilities for successful study. Policy and procedure must demonstrate and promote the inclusion of all students across campuses.

Accessibility and Disability Support

Each university will typically have a dedicated support team for students with disabilities, including those students with mental health and wellbeing concerns. Support staff in institutions can assist students to access all necessary support to ensure they can be included within university life and successfully complete their study. Students may have access to reasonable adjustments for assessment and should seek assistance from disability support areas if there are problems in accessing facilities, classes, online or face-to-face study requirements. Fostering an inclusive community of scholars is a fundamental objective of Australian universities, as inclusive environments encourage innovation, growth, and learning.

Disabilities can be physical, cognitive, or mental; because of this, reasonable adjustments are made in conjunction with each individual student’s needs, to ensure adequate and specific supports. If you need assistance, please contact your student disabilities and wellbeing unit who can help you with settling into university life and discuss the support available for your study. You may also find that your university has peer support groups for people with a disability. These can be a great way to connect with other students who may be able to share further information regarding available supports.

LGBTQIA+ STUDENTS AND ALLIES

Studying as a LGBTQIA+ Student

The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual/Aromantic+ (LGBTQIA+) communities face disproportionate challenges in contrast to their cisgendered and heterosexual peers, particularly regarding their experiences within educational settings (Cutler et al., 2022). Challenges can be rooted in stressors that cause LGBTQIA+ students to feel tokenised, misunderstood, or victimised (Cutler et al., 2022). Many universities are addressing these concerns by establishing LGBTQIA+ safe spaces on campuses, creating dedicated staff positions to support LGBTQIA+ students, developing pride networks and establishing LGBTQIA+ social clubs. If you are an LGBTQIA+ student, you have a right to feel safe while studying.

Safe Spaces

LGBTQIA+ safe spaces are typically physical spaces that can be located on campus where LGBTQIA+ students can study, meet with peers, and engage with university staff, all within the safety of a harassment, judgement and hate free zone. With the recent shift towards online learning, many universities now also offer virtual safe spaces for their LGBTQIA+ students via the university’s learning management system. Again, these virtual spaces are safe for LGBTQIA+ students to engage authentically with their studies, with each other, and with staff who are allies, or who are LGBTQIA+ community members themselves. Safe spaces are often an excellent place for students to ask questions, find resources, and be safely and appropriately referred to other university supports (Harpalani, 2017).

Pride Networks

Pride and ally networks are increasingly becoming commonplace at universities and provide both students and staff a pathway to connecting, whether they are LGBTQIA+ themselves, or are passionate allies who are interested in driving equity and advocacy. These networks provide empathetic, and sensitive support and guidance as LGBTQIA+ students navigate their way through university (Cutler et al., 2022). Members often must complete specified ally training to ensure these networks are informed and safe. Pride and ally networks are helpful in connecting LGBTQIA+ students with academic support, health and wellness guidance, and peer mentoring across the university. While these networks are helpful in navigating the formal aspects of university life, LGBTQIA+ social clubs help build informal peer connections which are beneficial for peer-to-peer learning, managing study stress and networking (Cutler et al., 2022).

Inclusive Environments

It is important to remember that all universities will have a Code of Conduct that students and staff must follow, which will typically outline the university’s stance on harassment or inappropriate behaviour, including towards LGBTQIA+ community members. Beyond this, Federal and State discrimination legislation in Australia provides guidance regarding acceptable behaviours which we must all abide by. Developing inclusive practices is an important skill to curate while studying at university as it is a desirable skill in the contemporary work environments (Lantz-Deaton & Golubeva, 2020). If you are an LGBTQIA+ student who has experienced discrimination at your institution in Australia, you will likely have access to advocacy and wellbeing supports, as well as formal complaint processes.

STUDENTS FROM CULTURALLY AND LINGUISTICALLY DIVERSE BACKGROUNDS

Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students in Higher Education

Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) students are essential to the make-up and success of universities. Australian universities over the decades have had richly diverse populations and frequently welcome many international students on their shores each year. In 2023, just over 324,000 international students arrived in Australia to study in the January to April period (Department of Education, 2023). Enabling and empowering culturally and linguistically diverse students within higher education institutions will strengthen the way in which we enrich our university communities, promote inclusive learning environments, and cultivate new perspectives and ideas. By embracing the diverse backgrounds, languages and experiences of students, university communities can develop respect and understanding, where students can freely express themselves and succeed in their studies.

To be successful at creating an enriched and vibrant culture, it is important for universities to establish good quality support services, to ensure student success. As many Australian universities have been established from a westernised and neo-liberal foundation, supporting all culturally and linguistically diverse students will require providing a range of supports in different areas.

Support Services and Student Life

Most higher education providers have a great range of support services available for students who may have additional cultural or linguistic requirements. For example, the university may offer English language support services and resources like appointments with language educators to keep you on track with your studies, academic English workshops, special tutorial groups, peer support groups, English conversation clubs, mentoring, self-help resources and more. All services are usually free for students and are conducted throughout your study journey. There is also support for you to observe any religious practices, and there should be safe places provided to pray, wash hands and feet, and safely practice your faith. Some universities may offer a chaplaincy service, or multi-faith service that supports the university community to practice their faith. Contact your university for more information on how to access these services.

Feeling a sense of belonging is important for students, particularly if you come from a different cultural or linguistic background. Many universities offer opportunities to join student events, cultural groups or clubs. These groups may hold special events during the year to celebrate significant cultural festivals or holidays, or they might organise opportunities to meet on a regular basis for social occasions. These clubs and societies can be a great way to meet other students, make new friends and feel connected to the university community.

Rights and Advocacy

Most universities also uphold a diversity and inclusion framework or policy, to ensure all students and staff feel safe and respected during their interactions with the university. There are policies and procedures in place for students who have experienced racism or discrimination, and it is important to seek out support and report any kind of unsolicited language or exclusionary practices. Seeking help and reporting racism or discrimination will not affect your grades or study success, and each case should be handled seriously and dealt with swiftly.

STUDYING AS A WOMAN

Traditionally, the university has been a male dominated institution, and it has only been in the last century that female participation in both graduation rates, and in staff and leadership roles has increased. Fortunately, female participation in higher education has grown exponentially over the last couple of decades across the world. According to a recent UNESCO report (2021), female enrolment globally in higher education tripled between 1995 and 2018, and not only do women now make-up the majority of undergraduate students, they are also more likely to complete their studies than their male counterparts. In Australia, this trend is also reflected in the 2021 census that shows that 58% of higher education students are women (Department of Education, 2022). These figures indicate that women are well and truly engaged and actively participating in higher education studies.

Study Sisterhood depicts the unique and powerful bond that women have with each other when congregating in historically male-dominated spaces. The mountains lining the bottom of the piece represent the women who have come before us, who paved the way for female representation in educational spaces. The variety in colours and sizes of women in the upper-left portion of the image is a nod to the diversity that is embedded in the female experience, from cis women to trans-women, to women-of-colour. Lastly, the upper-right corner represents the ‘winds of change’ that is brought on by intersectional feminism. Kc Rae.

It is important to note however, that higher education institutions remain largely patriarchal in their structures, culture, design, and processes (O’Connor, 2020). Women within these institutions, whether students or staff, continue to find themselves at disadvantaged within the system and must overcome barriers established and maintained by patriarchal systems that perpetuate their inequality. Although it is a great time to be a woman in the higher education system, nevertheless, the patriarchal culture of the institution can still have an impact on the way women study and operate.

Non-traditional Areas of Study for Women

Female and non-binary students may be interested in studying in an area that happens to be more male dominant and ‘less traditional’, such as STEM disciplines. In 2021 in Australia, about 16% of all domestically enrolled students were of women studying in non-traditional areas (Department of Education, 2022). Being a woman in these areas of study, you may face additional challenges. However, many universities wish to help break through these disparities by offering opportunities through scholarships and bursaries to help incentivise more women to study in the STEM disciplines. Look for what scholarships and opportunities are available to you by contacting your chosen university.

Female Students on Campus

Regardless of where you study, it is necessary to ensure that women feel safe and respected, both on campus and in online study. Many universities run ongoing campaigns around safety and respect while at university, and often publicise resources and/or a contact person, group or organisation who can provide support during your studies. This could include a student union or guild who can provide advocacy assistance to students and may provide resources to the university community about feeling safe and respected on campus, such as posters, social media support groups and events.

You may also find that there are particular interest groups specific to women and gender diverse students such as clubs, societies, and associations relevant to different faculty areas of study, post-graduate and more. Across Australia, there are a wide range of women’s networks that often run through the university that support women in higher education. Membership to these women’s networks is usually low cost or free and provides a valuable opportunity to network with other women and attend guest speaker presentations and networking events throughout the year. Many universities also offer health services to students which can include specific support for women’s and family health.

Safety and Respect

Alarmingly, in 2021, a report by University Australia (Heywood et al., 2021) reported that 1 in 6 students has been sexually harassed in an Australian university context and 1 in 20 has reported sexual assault. If you have ever been the target of sexual assault, domestic and family violence, harassment, or intimidation, it is important that you seek help for your personal, physical, emotional and psychological safety. It is against the law to harass or assault someone regardless of their position in society, or their relationship to you, so it is important to report it if you can. There are a range of support services not just in your university community, but also in the broader community as well; and any allegations can be made via the local police in your area. It is also essential that you take care of your mental health during such a distressing time. There are a range of free and confidential counselling services available to you in Australia, such as free counselling provided by the university and various community organisations (e.g., 1800RESPECT.org.au and lifeline.org.au).

Female intersectionality in Higher Education

Intersectionality is a term coined by Crenshaw (1989) that sheds light on the experiences of women of colour in the United States, and nowadays is used more broadly on a global scale to identify the varied intersections of identity such as race, culture, colour, sexuality, etc that an individual may encompass that impact their experiences of discrimination. In a higher education context, it is important to not only recognise intersectionality in individuals, but also work to actively ensure that each student feels empowered to succeed in their studies. Be sure to connect in with university networks, staff, colleagues, family and friends, and build a strong network of people who can support you and empower your decision making as you embark on your study journey.

DIVERSE ECONOMIC, LOCATION, AGE AND LIVING EXPERIENCES

Diverse identities and minority cohorts include more than race, ethnicity, nationality, gender or sexuality; these additional diverse identities can also influence a student’s experience and success at university. Therefore, it is important to understand what support and guidance might be available. Below is a table outlining some of the typical supports Australian universities may provide to several other priority student cohorts.

| Cohort | Supports |

| Low-income | Students from low-income backgrounds may find it useful to engage with their university’s wellbeing, welfare and support staff as these staff can provide guidance and assistance with accommodation, scholarship applications, navigating Centrelink processes, and financial literacy and budgeting. Furthermore, discussing career goals with your university’s careers and employability team can be a great way to help you keep on track with your studies. Balancing work and survival with study can be challenging, and your university is there to help manage that balance (Carnevale & Smith, 2018). |

| Rural and Remote | Students studying in rural and remote locations, or relocating from rural and remote locations to study, may find the transition to virtual study, or to a new location overwhelming (Partridge et al., 2021). It may be beneficial to talk to university welfare and wellbeing staff about accommodation support, mental health and counselling supports, and rural and remote specific scholarships. University Information and Communications Technology (ICT) departments can also be helpful in assisting rural and remote students in maximising the usability of the technology used to study. If you are a student from a rural or remote community it is important to stay engaged with your course content, peer mentoring, and social clubs virtually, as engagement can be helpful in managing stressful study periods and navigating the university experience. |

| First in Family | Navigating university as the first person in your family to do so can be an overwhelming process (King et al., 2019), but your university is there to guide you. Don’t be afraid to ask for help, or to clarify something. It may be useful to engage with a support or success officer who can help you understand the admissions and enrolment process, as well as refer you to other services if you need them. Engaging in peer-to-peer learning is a fantastic way to learn alongside others in an informal setting. Lastly, meeting with your university’s Academic Advisors can be a great way to develop academic skills that will support you throughout your study journey. |

| Mature Aged | Juggling studying with work, family or caring commitments can be a stressful experience for matured aged students (Heagney & Benson, 2017), but many universities have supports in place to assist in easing the impacts. Some universities offer on-campus child-care or medical services which you may wish to utilise to reduce commuting times. Whether you are new to study or are returning after a significant period away, your university’s Learning Advisors can assist with time-management and semester planning, academic writing, referencing, and other key study skills, and your wellbeing team can help support your mental health and wellbeing while you study. |

| Incarcerated | Studying while being incarcerated can be challenging (Marcus et al., 2019), but it does not have to be a journey you take alone or without support. You may be eligible for certain scholarships or bursaries to help pay for your study, books, or other key aspects of your learning. You may also be able to access information from Academic Advisors and Career Advisors to help you build your academic skills and prepare you for your future career. Chat to your Education Officer about what may be available to you. |

| Victims-survivors of Domestic and Family Violence | Many victims-survivors of domestic and family violence experience challenges during their study due to external influences, and they will often have intersecting diverse identities which may compound the challenge of studying (Lewer, 2019). However, universities offer several supports which victims-survivors of domestic and family violence may find useful in supporting their success. Many universities will offer security escorts on-campus, as well as safety apps for mobile devices, counselling, wellbeing, medical services, financial assistance (such as guidance with applying to Centrelink), and accommodation support. You are under no obligation to disclose your domestic violence experiences to your institution. |

It is important to remember that universities are diverse places, where people from a variety of backgrounds, experiences, and walks-of-life come together – your time studying at university is a perfect opportunity to reap the benefits of being involved in such a diverse community. Diverse environments improve your empathetic abilities, critical thinking skills, innovation, and prepare you for post-graduation experiences.

Mental Health Resources

Entering university is a significant transition, therefore it is important to know what mental health services are available at your university to help support and balance your wellbeing throughout your study. Many Australian universities host health services, including counselling services, which students can access, or, if the help required is beyond their scope, they can assist in referring you to off-campus supports. Most university students feel anxious, lonely, or depressed at some point during the year. We all have bad days, and sometimes bad days string into weeks. It’s OK to feel bad. What’s important is to acknowledge and work through your feelings whether that be formally, such as with a counsellor, or informally, such as talking issues out with a trusted friend. Stress and anxiety are common mental health concerns students may encounter; however, students can develop healthy coping mechanisms, and balance, to reduce the impact stress, anxiety, and perfectionism may have on their studies.

Stress

Like with any new adventure, starting to navigate university and its requirements can be stressful. Your ability to manage stress, maintain loving relationships, work effectively, and rise to the demands of university all impact your emotional and mental health. Feeling stressed can be perfectly normal, especially during exam time. It can motivate you to focus on your work, but it can also become so overwhelming you can’t concentrate. It’s when stress is chronic (meaning you always feel stressed) that it starts to damage your body. Stress that hangs around for weeks or months affects your ability to concentrate, makes you more accident-prone, increases your risk for heart disease, can weaken your immune system, disrupt your sleep, and can cause fatigue, depression, and anxiety (University of Maryland Medical Center, n.d.). Talking with a university counsellor may help you learn skills to manage your stress levels.

Anxiety

We all experience the occasional feeling of anxiety, which is quite normal. Unfamiliar situations, meeting new people, driving in traffic, and public speaking are just a few of the common activities that can cause people to feel anxious. It is important to seek help when these feelings become overwhelming, cause fear, or keep us from doing everyday activities. Anxiety disorders are one of the most common mental health concerns, and while there are many types of anxiety disorders, they all have one thing in common: “persistent, excessive fear or worry in situations that are not threatening” (National Alliance on Mental Illness, n.d.). Physically, your heart may race, and you may experience shortness of breath, nausea, or intense fatigue. Talk with a mental health care professional if you experience a level of anxiety that keeps you from your regular daily activities, including study.

Coping Mechanisms

Taking care of your mental health is incredibly important, especially when you find yourself in a new environment such as a university. Knowing what you are feeling and how to get help if you need it is imperative to ensuring your tertiary experience is positive and successful. In conjunction with formalised help, such as with a counsellor, you can implement your own healthy coping strategies to assist your mental wellbeing. The table below outlines some strategies to reduce stress, manage anxiety, and improve self-care practices. (See Table 3.3)

| Technique | Description |

| Exercise | Exercise comes in all shapes and sizes – from hitting the gym for a 90-minute session, to dancing in your loungeroom for 15 minutes to your favourite tunes. Exercise can help boost your energy and your mood (Headspace, 2021). |

| Fuel your body | Your brain requires a constant supply of energy to function. What you eat and are exposed to have a direct impact on its processes, your mood, and your ability to make good decisions. Eating a balanced diet can improve your sleep and concentration, which may help reduce stress and anxiety levels (Headspace, 2022). |

| Box Breathing | Box Breathing is a breath technique that can be done inconspicuously to help you refocus and recalibrate during peak times of stress or anxiety. To do box breathing you need to: breathe in for four seconds; hold for four seconds; breathe out for four seconds and hold for four seconds (Black Dog Institute, 2021) |

| Journalling | Journalling can help identify personal patterns in your emotions, note down helpful affirmations, and set goals (Headspace, 2018). |

| Meditation and Mindfulness | Meditation and mindfulness practices do not have to be an hour-long session of sitting cross-legged on the floor – it just has to be intentional and meaningful. Activities that allow you to be present and in the moment are most useful, such as yoga, colouring, grounding (meditation which includes a physical connection to nature e.g., standing barefoot on grass), or body scans (dedicated meditation that focuses on your body’s experiences and feelings in the moment) (Beyond Blue, 2022). |

While this table does not provide an exhaustive overview of mental illnesses and their impacts on one’s study career, it does outline how universities may be able to assist you in navigating mental health concerns while studying.

Conclusion

Navigating your way through university can, at first, be difficult and confronting. However, as explored throughout this chapter, there are multiple ways in which students can maximise their study experience, such as – asking for help and developing a list of support contacts, setting goals to help maintain accountability, engaging with Academic Advisors to assist in developing academic skills, and engaging with lecturers, mentors, and peers for formal and informal knowledge sharing experiences. Students from marginalised cohorts and with diverse backgrounds can access several supports tailored to their unique needs, which are designed to assist in improving their experience navigating their study journey. Lastly, universities offer supports for mental wellbeing, which are useful for students to access if study becomes difficult and confronting.

Key points

- All universities offer a range of learning support services. These can include academic advisors, mentors and peer support services and/ or programs.

- Your lecturers can also assist you. Use clear communication to tell them what you need help with. This can lead to a positive working partnership.

- Australian universities are working towards building inclusive learning environments and opportunities for all students.

- Students from, and with, diverse backgrounds and lived experiences will have access to a number of study supports.

- Universities provide a variety of tailored supports for students; with a disability, who are LGBTQIA+, that are women, who are from CALD communities, and who may be from other diverse backgrounds, such as mature aged students, incarcerated students, and remote students.

- Universities also offer a range of supports, for students to use to support emotional wellbeing and mental health, such as counselling and wellbeing services.

References

Beltman, S., Helker, K., & Fischer, S. (2019, November). ‘I really enjoy it’: Emotional Engagement of University Peer Mentors. International Journal of Emotional Education, 11(2), 50-70. Retrieved 2021, from https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/49174/1/IJEE11%282%29A4.pdf.

Bessarab, D. & Ngandu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in indigenous research. International Journal of critical Indigenous Studies. 3(1), 37-50.

Beyond Blue. (2022). Relaxation exercise. Beyond Blue. Retrieved August, 24, 2023 from https://www.beyondblue.org.au/mental-health/relaxation-exercises

Black Dog Institute. (2021, May 25). Square breathing exercise [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2FriSddUY84

Carnevale, A, P., & Smith, N. (2018). Balancing work and learning. Implications for low-income students. Georgetown University. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/Low-Income-Working-Learners-FR.pdf

Christie, H. (2014). Peer Mentoring in higher education: issues of power and control. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(8), 955-965. Retrieved April 2021, from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.934355

Cook-Sather A., Bovill C., Felton P. (2014). Engaging Students As Partners in Learning and Teaching: A Guide for Faculty. John Wiley & Sons.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167.

Cutler, B., Gallo Cordoba, B., Walsh, L., Mikola, M., & Waite, C. (2022). Queer Young People in Australia: Insights from the 2021 Australian Youth Barometer. Monash University, Melbourne: Centre for Youth Policy and Education Practice. https://bridges.monash.edu/ndownloader/files/35152024

Department of Education. (2023). International student monthly summary and data tables – Department of Education. Australian Government. Retrieved August, 14, 2023 from https://www.education.gov.au/international-education-data-and-research/international-student-monthly-summary-and-data-tables

Department of Education. (2022). 2021 Section 11 Equity groups – Department of Education. Australian Government. Retrieved August, 28, 2023 from https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/2021-section-11-equity-groups

Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (Austl.).

Harpalani, V. (2017). ‘Safe Spaces’ and the educational benefits of diversity. Duke Journal of Constitutional Law & Public Policy, 13(1), 117-166. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1136&context=djclpp

Headspace. (2018). Blog: how to start a journal. Headspace. Retrieved August, 14, 2023 from https://headspace.org.au/explore-topics/for-young-people/start-a-journal/

Headspace. (2021). Stay active for a healthy headspace. Headspace. Retrieved August, 14, 2023 from https://headspace.org.au/explore-topics/for-young-people/stay-active/

Headspace. (2022). Eating well for a healthy headspace. Headspace. Retrieved August, 17, 2023 from https://headspace.org.au/explore-topics/for-young-people/eat-well/

Heagney, M., & Benson, R. (2017). How mature-age students succeed in higher education: implications for institutional support. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(3), 216-234. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2017.1300986

Heywood, W., Myers, P., Powell, A., Meikle, G., & Nguyen, D. (2022). National Student Safety Survey: Report on the prevalence of sexual harassment and sexual assault among university students in 2021. Melbourne. The Social Research Centre. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2021-NSSS-National-Report.pdf

Hora M., Chen Z., Parrott E., Her P. (2020). Problemizing college internships: Exploring issues in access, program design and development outcomes. International Journal of Work Integrated Learning, 21(3), 235-252.

Kimmins, L. (2013). Meet-Up for success: The story of a peer let program’s journey. Journal of Peer Learning(6), 103-117.

King, S., Luzeckyj, A., & McCann, B. (2019). The experience of being first in family at university. Pioneers in higher education. Springer.

Lantz-Deaton, C., & Golubeva, I. (2020). Intercultural competence for college and university students. A global guide for employability and social change. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57446-8

Lewer, K. (2019). The impact of their life histories on the ways women who have experience domestic violence decide on and engage with university study [Doctoral dissertation, University of Wollongong]. University of Wollongong Thesis Collection. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1/676

Marcus, K., Hopkins, K., & Farley, H. (2019). Beyond incarcerated identities: Identity, bias and barries to higher education in Australian prisons. International Journal of Bias, Identity and Diversities in Education, 4(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJBIDE.20190101

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (n.d.). Anxiety Disorders. https://www.nami.org/NAMI/media/NAMI-Media/Images/FactSheets/Anxiety-Disorders-FS.pdf

O’Connor, P. (2020). Accessing Academic Citizenship: Excellence or Micropolitical Practices? In S. Sumer (Ed.), Gendered Academic Citizenship: Issues and Experiences (pp. 37–64). Palgrave.

Partridge, H., Power, E., Ostini, J., Owen, S., & Pizzani, B. (2021). A framework for Australian universities and public libraries supporting regional, rural and remote students. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 70(4), 391-404. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2021.1959842

Pascarella, D., & Terenzini, P. (2005). How college affects students. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Phillips, L., Bunda, T. & Quintero, E. (2018). Research through, with and as storying. Routledge.

Shaniakos, T., Penttinen, L., & Lairio, M. (2014). Peer Group Mentoring Programmes in Finnish Higher Education – Mentors’ Perspectives. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 22(1), 74-86. Retrieved from http://doi-org.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/10.1080/13611267.2014.882609.

Terare, M. & Rawsthorne, M. (2019). Country is yarning to Me: Worldview, health and well-being amongst Australian First Nations People. British Journal of Social Work. 50, 944-960. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz072

Terrion, J.L., & Leonard, D. (2007, May 17). A Taxonomy of the characteristics of student peer mentors in higher education: findings from a literature review. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 15(2), 149-164. Retrieved April 2021, from https://doi-org.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/10.1080/13611260601086311.

UNESCO. (2021). Women in higher education: has the female advantage put an end to gender inequalities? In Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 12(2). http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en

University of Maryland Medical Center. (n.d). University of Maryland Medical Cente. https://www.umms.org/ummc

Walker, M., Fredericks, B., Mills, K. & Anderson, D. (2014). Yarning as a method for community based health research with Indigenous women: The Indigenous Women’s Wellness Research Program. Health Care for Women International, 35(10), 1216-1226.