Reading

Linda Clark

Introduction

Reading and consuming information are increasingly important today because of the amount of information we encounter. Not only do we need to read critically, but we also need to read with an eye to distinguish fact from opinion and identify credible sources. In academic settings, we deliberately work to become stronger readers. Take advantage of all the study aids you have at hand, including human, electronic, and physical resources, to increase your performance. This chapter will provide you with an understanding about the different ways of reading for university study, some reading strategies for you to try and information about different types of sources.

Ways of reading

There are generally five ways of reading which include: 1) pre-reading, 2) skimming, 3) scanning, 4) detailed reading, and 5) critical reading.

Pre-reading

During the pre-reading stage, you can easily pick up on information from the cover and the front matter that may help you understand the material you’re reading more fully or place it in context with other important works in the discipline. Look for an author’s biography or note from the author. To identify the topics covered and how the information fits into the subject, look for headings in larger and bold font, summary lists, and important quotations throughout the textbook chapter. Use these features as you read to help you determine what are the most important ideas.

Sometimes you can find a list of other books the author has written near the front of a book. Do you recognise any of the other titles? Can you do an internet search for the name of the book or author? Beyond a standard internet search, try the library’s database. These are more relevant to academic disciplines and contain resources you typically will not find in a standard search engine. If you are unfamiliar with how to use the library database, ask a librarian.

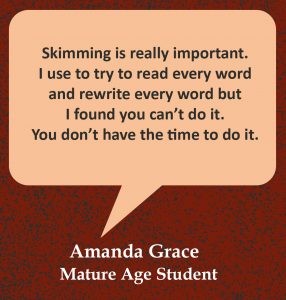

Skimming

Skimming is not just glancing over the words on a page or screen. Effective skimming allows you to take in the major points of a passage to determine the usefulness of the source.  If the source is useful, you will then need to engage in a deeper level of active reading, but skimming is the first step—not an alternative to deep reading. Skimming is useful as it gives you a brief overview before reading in more detail and assists with comprehension. Instead of reading every word, skimming involves spending a brief amount of time per page, quickly looking at:

If the source is useful, you will then need to engage in a deeper level of active reading, but skimming is the first step—not an alternative to deep reading. Skimming is useful as it gives you a brief overview before reading in more detail and assists with comprehension. Instead of reading every word, skimming involves spending a brief amount of time per page, quickly looking at:

- the contents

- the headings and sub-headings

- the abstract or introductory paragraph

- the conclusion

- any diagrams or graphics you think are important

End your skimming session with writing a few notes or terms to look up, questions you still have, and an overall summary. Recognise that you likely will return to that book or article for a more thorough reading if the material is useful.

Scanning

Scanning involves reading a text with a specific purpose in mind. Rather than reading every section, scanning involves quickly looking for relevant information only. Use this technique when you are reading to find specific material or data related to an assignment topic, or to find answers for questions (e.g. for tutorial activities).

Detailed reading

Detailed reading is when you focus on the written material, really looking to gather specific information or evidence on a topic. This type of reading will provide you with a more in-depth understanding of the specific information, facts, positions and views on a topic. In detailed reading you may be looking for new information or a different perspective. Is this writer claiming a radical new definition for the topic or an entirely opposite way to consider the subject matter, connecting it to other topics or disciplines in ways you have never considered? Also, try to consider all the possible perspectives of a subject as well as the potential for misunderstanding due to personal biases and the availability of false information about the topic.

Critical reading

Critical reading requires you to actively engage with the written material by questioning and evaluating the quality and relevance of the information for your task. This may include analysing the author’s strategies, methods and reasoning. Critical reading is a vital skill to develop to help you become a better analytical thinker and writer.

The following are some questions to consider when reading critically.

- Are there any contradictions?

- Is an argument developed?

- Is it logical?

- Is the text biased?

- Is there supporting evidence and how valid is it?

- Are there any ‘hidden’ assumptions?

- Is there an alternative conclusion given?

- What alternative perspectives are available in the wider literature?

Reading Primary and Secondary SourceS

Primary sources are original documents we study, which include letters, first editions of books, legal documents, and a variety of other texts. When scholars look at these documents to understand a period in history or a scientific challenge and then write about their findings, the scholar’s article is considered a secondary source. Primary sources may contain dated material we now know is inaccurate. They may contain personal beliefs and biases that the original writer didn’t intend to be published openly, and it may even present fanciful or creative ideas that do not support current knowledge. Readers can still gain great insight from primary sources, but readers need to understand the context from which the writer of the primary source wrote the text.

Likewise, secondary sources are inevitably another person’s perspective on the primary source, so a reader of secondary sources must also be aware of potential biases that may persuade an incautious reader to interpret the primary source in a particular manner. A literature review is an example of a secondary source. When possible, you should attempt to read a primary source in conjunction with the secondary source.

Recursive Reading Strategies

One fact about reading for university courses is that you may end up doing more re-reading. It may be the same content, but you may need to read the passage more than once to detect the emphasis the writer places on one aspect of the topic or how frequently the writer dismisses a significant counterargument. This re-reading is called recursive reading.

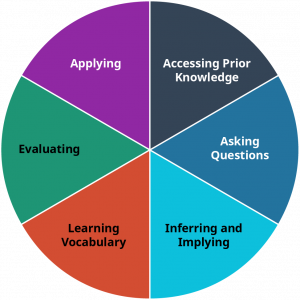

When reading at the university level, you are trying to make sense of the text for a specific purpose. You should consider what the writer of the piece may not be including and why. This is why reading for comprehension is recursive. Specifically, try to see reading as a process that is far more circular than linear. For example, you’ll need to go back and re-read passages to determine meaning and make connections between the reading and your discipline or context. This recursive reading strategy builds on the ‘Ways of Reading’ that we explored previously. Let’s break the recursive reading strategy into manageable chunks, because you are actually doing quite a lot when you read.

Accessing prior knowledge

When you read, you naturally think of anything else you may know about the topic, but when you read deliberately and actively, you make yourself more aware of accessing this prior knowledge. Have you ever watched a documentary about this topic? Did you study some aspect of it in another class? All of this thinking will help you make sense of what you are reading.

Asking questions

Humans are naturally curious beings. As you read actively, you should be asking questions about the topic you are reading. Don’t just say the questions in your mind; write them down. You may ask: Why is this topic important? What is the relevance of this topic currently? Was this topic important a long time ago but irrelevant now? Why did my lecturer assign this reading?

Inferring and implying

When you read, you can take the information on the page and infer, or conclude responses to related challenges from evidence or from your own reasoning. A student will likely be able to infer what material the lecturer will include on an exam by taking good notes throughout the classes leading up to the test. Writers may imply information without directly stating a fact. You have to read carefully to find implications because they are indirect, but watching for them will help you comprehend the whole meaning of a passage.

Learning vocabulary

Vocabulary specific to certain disciplines helps practitioners in that field engage and communicate with each other. As a potential professional in the field you’re studying, you need to know the lingo. You may already have a system in place to learn discipline-specific vocabulary, so use what you know works for you. Two strong strategies are to look up words in a dictionary (online or hard copy) to ensure you have the exact meaning for your discipline and to keep a dedicated list (glossary) of words you see often in your reading. You can list the words with a short definition so you have a quick reference guide to help you learn the vocabulary.

Evaluating

When you evaluate a text, you are seeking to understand the presented topic in detail in order to engage with it. Depending on how long the text is, you will perform a number of steps and repeat many of these steps to evaluate all the elements the author presents. When you critically evaluate a text, you need to do the following:

- Scan the title and all headings

- Read through the entire passage fully

- Question what main point the author is making

- Decide who the audience is

- Identify what evidence/support the author uses, and is the evidence valid?

- Consider if the author presents a balanced perspective on the main point

- Recognise if the author introduced any biases, contradictions or assumptions in the text

Allow Time for Reading

You should determine the reading requirements and expectations for every class early in the semester. You also need to understand why you are reading the particular text you are assigned. Do you need to read closely for minute details that determine cause and effect? Or is your lecturer asking you to skim several sources so you become more familiar with the topic? Knowing this reasoning will help you decide your timing, what notes to take, and how best to undertake the reading assignment. Depending on your schedule, you may need to read both primary sources and secondary sources. You may also need to read current journalistic texts to stay current in local or global affairs. To avoid feeling overwhelmed, schedule reading time when creating your weekly study timetable to allow you to time read and review. You can make time for reading in a number of ways that include scheduling active reading sessions and practising recursive reading strategies.

Conclusion

Reading is one of the most important skills you need for studying at university. The strategies that have been explored in this chapter will help you to get the most out of your reading time.

- Pre-reading helps you understand the context of what you are reading.

- Skimming helps you to determine the usefulness of the source.

- Scan to find specific information related to your assignment topic.

- Detailed reading helps you to gather evidence on your topic.

- Use critical reading to question and evaluate the relevance of the information in the source

- Identify if you are reading a primary or secondary source, and watch for biases.

- Recursive reading strategies involve accessing prior knowledge of the topic; asking yourself questions about importance; inferring meaning; learning new vocabulary, and; evaluating the validity, evidence and bias of the author.

- Schedule weekly reading time.